1. Introduction

The concepts of value and monument set out by Riegl in The Modern Cult of Monuments are part of an open and constantly evolving debate. Françoise Choay states that

“…any artefact built by a community to remind itself or to make other generations remember people, events, sacrifices or beliefs will be called a monument. […] Among the immense and heterogeneous background of historical heritage, I have chosen as an exemplary category the one that directly concerns the setting in which our lives take place: built heritage”

This concept of heritage can be understood as a multifaceted reality, which, before intervening on a heritage asset, calls for the decoding and understanding of the heritage problem that materialises or is accounted for in attributes which characterise it and embody values [

2]. Consequently, values have played a key role in “defining and directing conservation of built heritage” [

3]. These values-based approaches in heritage intervention processes draw directly from the Burra Charter (1979) and the World Heritage Convention (1972) and have acquired particular strength during the 21st century, generating a new debate on the classification and categorisation of such cultural values [

4,

5]. Focused on the identification of values and cultural assessment, the applied methodologies are complex as they are working with

significance, a constantly evolving concept [

6,

7]. This debate appears as a dynamic and changing action, which depends entirely on the heritage asset in question. As a result, some authors claim that “any attempt to categorise all values is determined to fail” [

8]. For this reason, the present moment is focusing on the “discursive approach” and not on the identified values classification [

9].

Along these lines, certain trends exist that have advocated values-based approaches in heritage conservation since the 1980s, and which are currently considered as the most suitable processes in this architectural practice [

10]. This is so because such values are what justify the exceptional status of a heritage asset for a community [

2]. Despite this, some experts confirm that on occasion, values-based approaches are not the most correct methods when intervening in heritage, because “decisions are based on incomplete understandings of heritage and its values” [

5]. Hence, it becomes crucial to contrast knowledge derived from the design processes within architectural practice in interventions with the methodological procedures employed in heritage studies. In this way, we can examine how rehabilitation actions enter into dialogue with these values-based approaches, and clarify whether they take heritage assessment as a starting point in this process.

If we are to understand the dynamic nature of values, it is important to go beyond their traditional consideration from the perspective of the history and materiality of places. Indeed, the field is now characterised by taking into account citizens’ perceptions. This paper focuses on the opportunity to identify the interaction between heritage studies and design practice but surrounded by participatory processes. In the same way, the proposal is understood as a tool to improve the quality of the results of a heritage intervention project by placing values at the centre of the discussion. The mechanisms envisaged for this are the Heritage Impact Assessments (HIA), which are still refining their approach to monitoring values [

6].

Therefore, this research proposes an approach to heritage intervention which has as its main objective establishing a comparative dialogue between the methodologies consolidated in heritage studies and the design processes undertaken within the discipline of architecture. This is undertaken to elucidate whether this proposed dialogue is operational and whether the practice of architectural rehabilitation needs to be brought closer to heritage studies in order to better explain design strategies and decisions.

In order to achieve this objective, this article is organised by first describing the working methodology, and then presenting the case study to be applied: a contemporary intervention on a cultural asset in a World Heritage area. Once the object of study has been contextualised, the identification of values is approached on the basis of a classification established according to their origin. By comparing the values recognised and reformulated in the project, the critical discussion makes it possible to prioritise the fundamental values. Mindful of the controversy generated by the categorisation or classification of values in a heritage asset for intervention [

5], we take the case of Trinity College (TC) in Coimbra to put the proposed methodology into practice (

Figure 1). This contemporary rehabilitation by Aires Mateus is designed as an intervention within the framework of a values-based approach.

This case study was chosen based on the contemporary nature of the architectural intervention, the simultaneity of the design process with the declaration of the University of Coimbra (UC) as a World Heritage (WH) Site, and the fact that this architectural intervention is originally based on the theory of value. The architects conducted a prior heritage assessment to support their intervention design strategy. Finally, it presents an opportunity to examine heritage intervention from the perspective of Portuguese architectural practice, and foment a cross-examination within the general guidelines and the internationally accepted heritage intervention criteria.

This comparative methodological approach between heritage studies and architectural praxis is especially relevant in the field of heritage intervention, since it is an experimentation that seeks a potential transfer to other contemporary heritage interventions, also adding the critical exercise of the interpretation of values as a preliminary step before the intervention project.

2. Architectural Context

This research is inserted in the Portuguese architectural context of contemporary heritage intervention, which is currently characterised by a dichotomy in terms of how this type of architectural practice is approached.

To begin with, it is necessary to mention that Fernando Távora (1923–2005) was one of the most representative figures of modern Portuguese architecture and, consequently, one of the precursors of the current trends in heritage intervention in this country. In 1945, he published the manifesto

O problema da casa portuguesa (republished in 1947 [

11]), in which he began to speak of the ‘third way’ which he cites as ‘an evolution of modern architecture with the capacity to identify itself with tradition [

12].

These lessons are those that would mark what is currently known as the

Escuela do Porto, a contemporary trend in Portuguese architecture based on the models of the Modern Movement. It consisted of a number of architects trained at the Escola Superior de Belas-Artes do Porto (ESBAP), which is now divided into the Faculty of Fine Arts and the Faculty of Architecture of the University of Porto. This attitude ‘is nothing more than the radical rejection of all scenographic and anecdotal stylism proposed as a pretext or alibi for the death of totalitarian visions and the mobility and dispersion of the contemporary world’ [

13]. This group of architects understands intervention in built heritage as a superimposition of languages that gives a new form to the pre-existence, using it as a material of the project. They work on these interventions by interpreting them in the flow of time, assuming the different juxtapositions that have taken place on them and understanding contemporary intervention as another layer superimposed on it [

13].

On the other hand, the interventions that take place within the architectural context of the schools of Lisbon have an approach closer to the Charter of Venice (1964), which determines that any new action must be shown as such and be differentiated from the monument itself. This has generated a way of intervening in the heritage that respects the values of scale and texture of the pre-existing building, but totally differentiates itself from it, with minimal opportunities for interference or interaction between the intervention and the original building [

13].

In Portugal, therefore, the debate on how to approach this type of architectural action continues to rage. On the one hand, there is the aspect of intervention on the building, as one more layer of this palimpsesto. On the other, there are those who align themselves with international recommendations and advocate non-interference in the pre-existence, so that the addition is understood as such and, consequently, differentiated from the original. Despite this, in order to avoid generalisations in this matter, the theory of intervention that advocates the singularity of each case is gaining strength.

3. Methodologies in Dialogue

This study is based on the heritage project methodology developed by the Andalusian Institute of Historical Heritage (IAPH), which is based on the motto “to know in order to intervene”. It is a process based on four phases:

knowledge (studies),

reflection (project values),

intervention (execution, enhancement) and

maintenance (management). The main resources used are document management and graphic representation. In a transversal way, transfer, participation and sustainability run through the whole process [

14,

15,

16,

17]. While this methodology, which is already consolidated, focuses on the knowledge and assessment of a heritage asset with a view to a future heritage intervention, this methodological innovation in dialogue with the project processes approaches the heritage asset after the final intervention has been carried out. Heritage assessment is understood as a dynamic and changing process, since “values are generated through continuous learning processes and their definitions change over time, giving rise to diversity. The measurement of values is most appropriately expressed in terms of monitoring their impact” [

18].

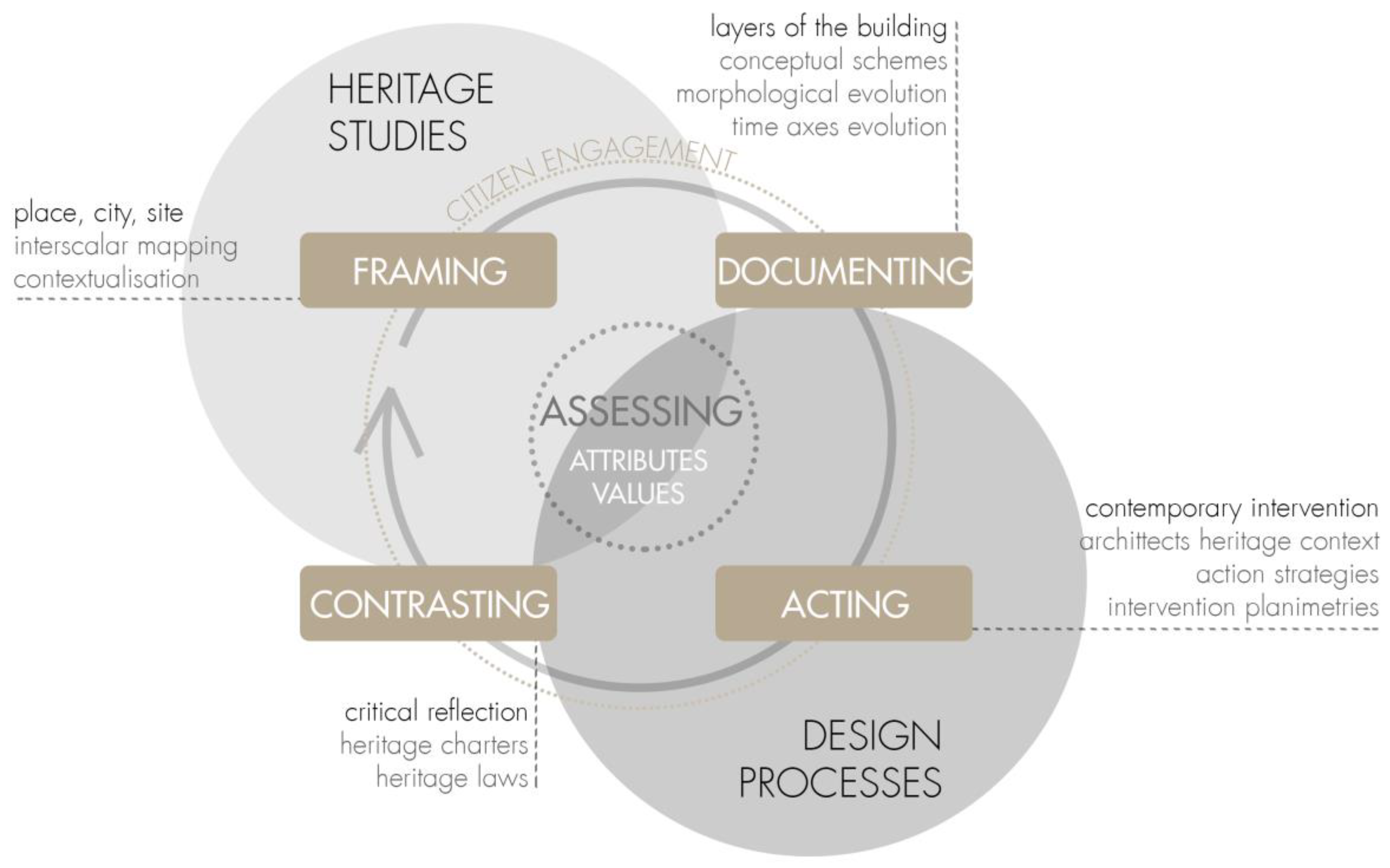

Therefore, a methodology based primarily on the one applied in heritage studies is presented, and a dialogue is set up with the design processes of heritage intervention (

Figure 2). This takes place when analysing the rehabilitation of a building and contrasting it with the international heritage intervention context. Throughout this process, particular attention is paid to the cultural assessment of the monument and the intervention, which must go hand in hand with the needs of the community [

19].

The first step is to search for and document all of the information relating to the heritage asset—its location, its construction and its history—from a territorial and urban perspective. This approach provides an integrated view of the property, highlighting all of the shared physical and heritage resources that link these assets to the city.

Secondly, the building and its different layers are analysed and characterised in more detail, paying particular attention to its morphological evolution up to the present day. Emphasis is placed on a more individualised view of its spatial units, its materiality and its typological issues.

This is followed by a more detailed technical analysis of the contemporary intervention of the case study, understood as the final stratum of the building. Project strategies are subject to close scrutiny, to determine whether the intervention is based on monument values.

Finally, before showing the results, the intervention is placed in an international context, to ascertain how it responds to current trends in heritage intervention. To this end, the alignment of this project with international charters on built heritage intervention is checked.

4. Case Study—Colégio Da Trindade

4.1. Context—Coimbra and Its University up to Its Inclusion on the World Heritage List

Coimbra is a Portuguese city located in the central part of the country, belonging to the district of Coimbra. Regarding the origins of the city, there is evidence of its existence as far back as in Roman times, when it was built on a settlement called Æminium, which stood on a hill next to the river Mondego. It was the capital of Lusitania for a lengthy period, until the 13th century. The city is considered one of Portugal’s main regional centres, outside the metropolitan areas of Lisbon and Porto, and a hub for the country’s entire central region. It has a dense urban area, and is known chiefly for its university, which has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2013. As such, it has a cultural life that generally revolves around the University of Coimbra, which has always attracted notable writers, artists and academics, giving it a reputation as the Lusa-Athens (or Athens of Lusitania) [

20].

The university, meanwhile, was transferred between this city and Lisbon several times between the 13th and the 16th centuries. In 1537, after finding apparent stability in Lisbon, the Portuguese king at the time, Joao III, decided to re-establish the Portuguese university ex-novo and move it once again to Coimbra. The aim of this decision was to create a new university centre on a par with its European counterparts. Advantageously, Coimbra was supported by a network of colleges that Lisbon lacked [

20].

As a result, two major urban planning interventions were carried out over time. These were both quite clearly defined, but simultaneously contrasting in their logic: the linear model of the Rua da Sofia, and a grid layout set out over a series of roads and streets for the construction of new schools, known as the Alta (

Figure 3):

In 2013, these two areas of the historic centre were added to UNESCO’s list of WH Sites (

Figure 4). In addition to having been the only Portuguese-speaking university in the world until 1911, the UNESCO declaration valued its remarkable scientific and cultural relevance, as well as its vast urban and architectural heritage. To be declared a WH Site, this complex met three of the criteria imposed by UNESCO for inclusion on the list [

21].

This distinction was primarily awarded based on the site’s architectural and urban quality, as it is a clear reflection of the urban evolution it has witnessed, and also for the values of

authenticity—it encompasses all of the elements that demonstrate its Outstanding Universal Value as a university city, and its architectural ensemble illustrates the various periods of university development related to the ideological, pedagogical and cultural reforms—and

integrity: each of the university’s buildings is representative of the historical, artistic and ideological periods in which it was built [

21].

4.2. The College, from Its Beginnings to Its Intervention in the 21st Century

TC was established in 1552, in some pre-existing houses next to the Old Cathedral of Coimbra. The collegiate priests settled here leading a cloistered, regular life, under conditions of silence and meditation. However, it was not until 1562 that the construction of this building commenced on an empty plot in the Upper Intramural Area [

22].

The building was one of the first programmatic designs, later used in other university colleges in Coimbra. It is a church with an adjacent cloister, to which a U-shaped volume is attached to house workshops on the ground floor and the cells on the first floor around a courtyard. These spaces were adapted to the new urban layout in this part of the city.

Constructively and aesthetically, this building was composed of a U-shaped volume with two corridors around a courtyard, which hosted the dormitory area, divided into cells on the different floors, in the eastern part. The western part accommodated the main uses of a conventual building: a classical church and a square-shaped cloister, which had four galleries comprised of four-arched vaults supported by brick edges. The northern and eastern façades were very simple, with a series of openings to serve programmatic functional needs. The western façade, meanwhile, was characterised by the church, the gabled roof of which was flanked by two towers, one of them being a balcony onto the southern façade, reminiscent of an Italian

loggia which afforded views of the Mondego River [

23].

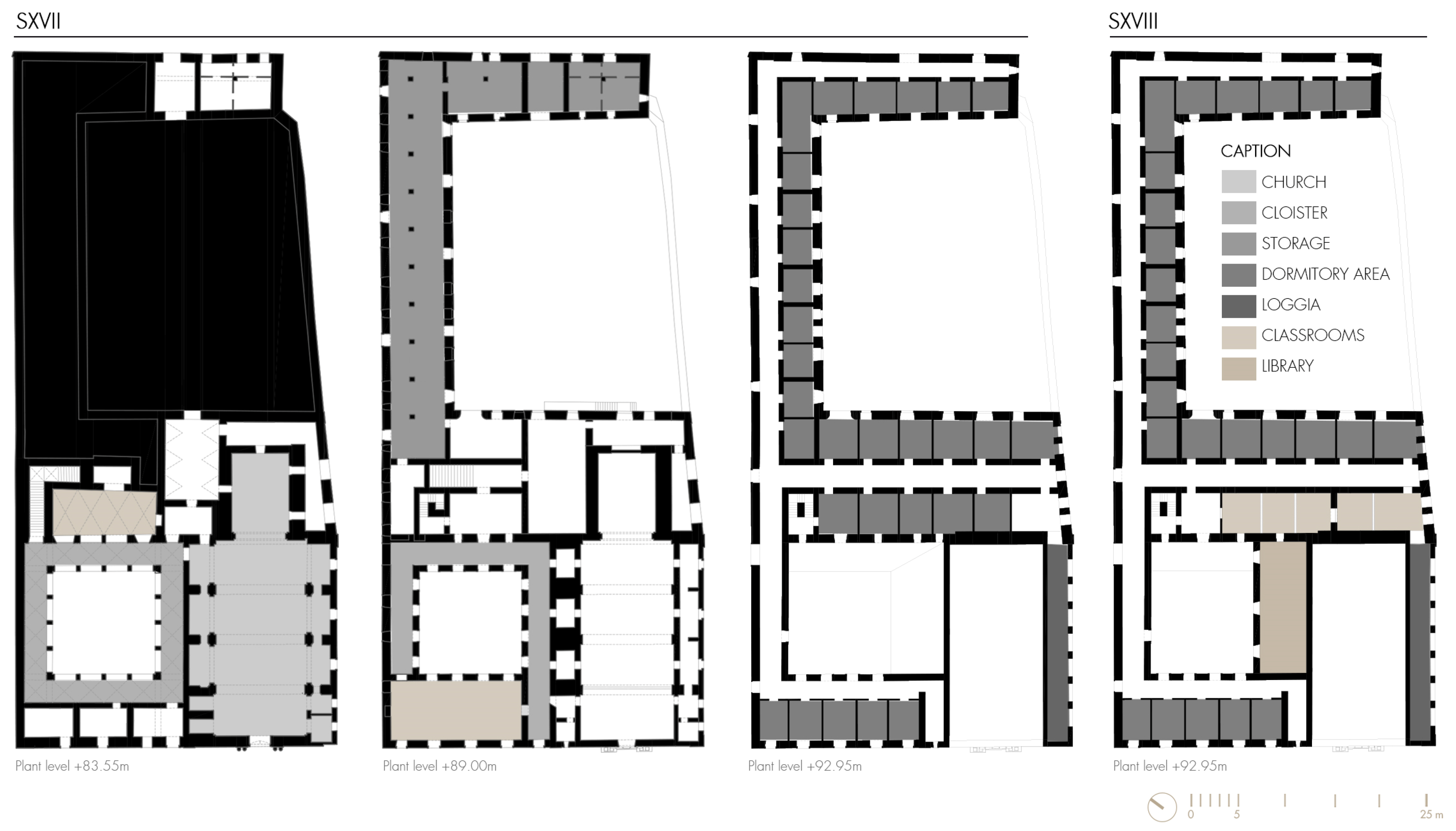

As the building emerged as a university college, its spaces were necessarily transformed with the passage of time and the evolution of society, according to its activities (see

Figure 5 and

Table 1). In the 21st century, it was again transformed, on this occasion by Aires Mateus, in order to continue its life and service to the UC.

Finally, this building, coupled with the university colleges of Coimbra, is a rather peculiar architectural case, since at the time of the re-foundation of the UC, there were no references in Portugal for this type of construction. Its design ended up being subordinated to its programme of usage and the new teaching methods of the time. It is a typology composed of a church and an adjacent cloister, a repeated structure that coexisted with residential and teaching uses.

4.3. Interventions Prior to the Contemporary Project—A Reading Based on the Strata of the College

The morphological development of the building was primarily influenced by changes in ownership and alterations in its usage over time. In the 18th century, the canons of the Holy Trinity made modifications to the body of the building which, on the level of the programme of functions, reflected the educational concerns of that period. The most significant changes were the addition of a library and some classrooms on the +92.95 m floor, above the cloister and left-hand chapels of the church (

Figure 6).

Following the dissolution of the religious orders in 1834 and the subsequent public auction in 1849, the division into two halves was accentuated when the eastern part became private property. The building was divided into residential units on this side, while the western part became the property of the National Treasury [

23], which transformed the church and its surrounding buildings into the District Court of Justice.

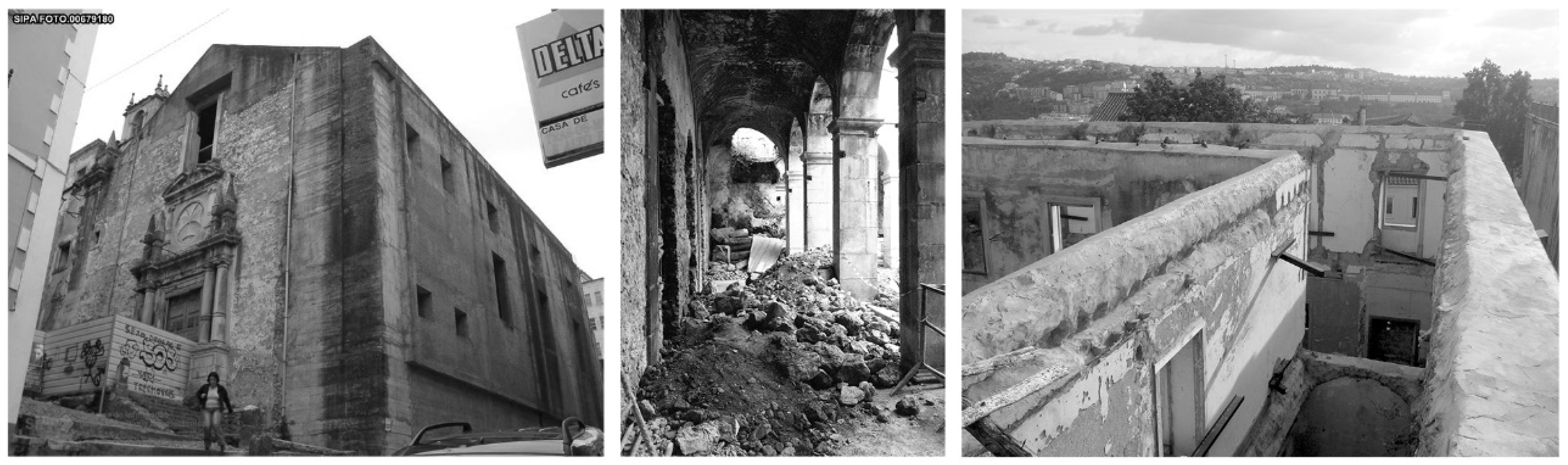

The building was maintained as such until 1988, when the south façade on the Couraça de Lisboa, next to the church, and the top two floors of the central part collapsed, including the south

loggia. Immediately afterwards, stabilisation work was carried out on the College and a project was drawn up by the architect Simoes Dias for the construction of the European College and University Support Facilities in this building. Perhaps due to a lack of funds, the work was interrupted and the focus shifted to stabilising the building [

23].

Like the cloister, the Church of the Holy Trinity was one of the spaces least affected by the transformations and the passage of time, despite having undergone some minor interventions. In terms of volume, it lacks the loggia on the south elevation, as it was never rebuilt after the collapse in 1988 and, in addition to being used as one of the recreational spaces of the school, it was symmetrical with the bell tower.

The last remains of the Alta of Coimbra

At the beginning of the second decade of the 21st century, the building remained largely intact, and the body of the church and the cloister on the ground floor, as well as the load-bearing walls delimiting the outer perimeter of the school, were still recognisable (

Figure 7). “Throughout the project process, the architects had two significant interlocutors for both the proposal and its problems: the UC, as the client, and time itself, which played an important role in determining which elements would be maintained in the intervention” [

24].

5. The Inhabited Ruin—The Aires Mateus Intervention Project

“This project took a long time to be approved because our proposal, contrary to what was asked for in the competition, was not about stopping time. Instead, we were interested in everything that, even when working at compression, was timeless and as a result, had been preserved. We kept elements that belonged to different periods, but which had the strength to remain” [

25].

The issue of time becomes even more evident during the years that passed between the presentation of the proposal by Aires Mateus (2001) and the start of the work (2013), which were key to the gestation of the project. This time exerted a progressive decanting effect on the ensemble, and it was the building itself which signalled what was to be maintained and what was not [

26]. So much so that during this period, another defining event took place for the UC and, in this case, for TC: the inclusion of the UC in the UNESCO WH list, a key event in the process of the project “because it entailed a much greater scrutiny of the development of the work itself” [

25].

The loss of certain elements over the course of the project influenced the subsequent reflection of the intervention. The proposed inclusion of newly built volumes inside TC, conceived with their temporary purpose and which could eventually disappear over time, in the same way as the old roofs and slabs did, make the intervention “reversible in nature” [

27], highlighting Aires Mateus’ understanding of the passage of time in architecture (

Figure 8).

The authors’ use of the concepts of

eternal and

ephemeral was brought into dialogue with the values previously expressed by A. Riegl (1982), and this could constitute the initial hypothesis of the project, starting from a conceptual strategy of cleaning up the ephemeral, a task ultimately realised through the passage of time. For that reason, in the intervention “it became mandatory to assume contemporaneity, proceeding with the creative valorisation with the artefacts of this age, and bear witness to a vision for the future” [

23].

5.1. Materiality—Eternal Value vs. Ephemeral Value

It is by understanding the concepts and values set out above that Aires Mateus’ proposal for intervention in time takes shape from the moment they win the competition until construction finally begins:

“Constructively, what was ephemeral was made in wood, and what was eternal was made in stone. Everything ephemeral was made by tensile work, everything eternal by compression. So, we discarded what was subject to traction, and replaced it with a new layer, which also works in traction, but, in this case, instead of using wood, we used steel (…). What matters is the intention of each element in relation to time. Our impression is that in 50 years’ time, someone will come along who will decide to throw away what seems ephemeral—what we have built—and in its place will build another project, also ephemeral. But the eternal will always remain”

The time reversibility strategy was materialised by adding a new steel layer inside that which was pre-existing, emphasising the concept of massiveness, and so some of the exterior walls were widened in order to take in some vertical connections and infrastructural elements [

23] (

Figure 9).

As for the material and construction aspects, in most of the building, only the thick masonry walls had been left standing, which were presented as elements of continuity capable of influencing the project. This question therefore shows the dreamlike and poetic capacity of these ruins, accentuating the contrast with the subtlety of the new intervention, in which “the use of neutral materials defined spatiality as the centre of reflection and the respective qualities of perception, from which emerged the play of light and shadow” [

23].

The upper floors and roofs were practically in ruins at the time of the intervention, and this is where the proposal seeks to operate in a more profound way. This is why the existing façades are used to build new volumes between them.

5.2. An Architectural Intervention with an Urban and Social Vocation

A qualified intervention on a heritage site can be considered a source of positive contamination on nearby or surrounding buildings, as it can promote a dynamic of rehabilitation and urban regeneration in that environment. This was the main intention of UC, which has always engaged in a conservation and restoration policy of its material assets, seeking to enhance each building, and also trying to maintain their intangible value in any way possible [

28].

This strategy of urban and heritage regeneration emerges as a multidimensional action, where the social component is key to the determination and development of the architectural intervention, understood as a confrontation with an object wherein one must pay attention to the associations inherent within it in order to understand its social connections, “giving rise to a conception of place that is relational and always under construction. The experience with our space-time has the capacity to affect emotionally” [

29]. It is understood as a scenario which enables some encounters and relationships between different complex situations, where the relationships between them are what matters, more than the objects themselves [

30].

However, this proposal for the integration of the public space as a whole with its related built heritage is even more evident when analysing Aires Mateus’ intervention on TC. This strategy of continuity between the public spaces and the building becomes apparent in this project in one key aspect: the original roof of the building was at a similar level to that of the main square of the Paço das Escolas, the main university building located next to TC (

Figure 10). This was because, at the time of construction, the regulations set a limit on the building’s heights and floors so that it would not pose a physical barrier between the square and the landscape and its relationship with the Mondego River (landscape value).

The same strategy is sought by Aires Mateus with this intervention. In their project, the architects define a roof with the same volume and height as the original project but introduce a variant: instead of using a traditional red tile roof as required by the regulations, they propose a sloping roof with a

lioz stone in light tones [

23]. The purpose of this is to lend visual continuity in conjunction with the paving of the adjacent square, creating a symbiosis between the two constructions, in this case uniting the urban space with its built heritage.

6. Mapping Cultural Values by Introducing the Intervention in an International Context

The complexity of working with values is assumed by different authors who understand that “solving the puzzle of values is a central part of managing sites” [

31]. It is also important to manage both types of values, tangible and intangible, but at the same time understanding that based on the shift towards Societal Values, all heritage values are “intangible” if we consider the broader meaning of heritage, which is seen as a social construction [

32].

Moreover, the dynamic changes that the historic urban landscapes of our cities and the monuments within them undergo require analysis and study of the territory in which they are inserted, the elements of heritage significance that characterise them, and a complete identification of this heritage. This approach towards the objects of the past, with regard to heritage, is reflected in the succession of International Charters from institutions such as UNESCO, which “have generated the idea of cultural value with which we now recognise the extensive heritage phenomenon” [

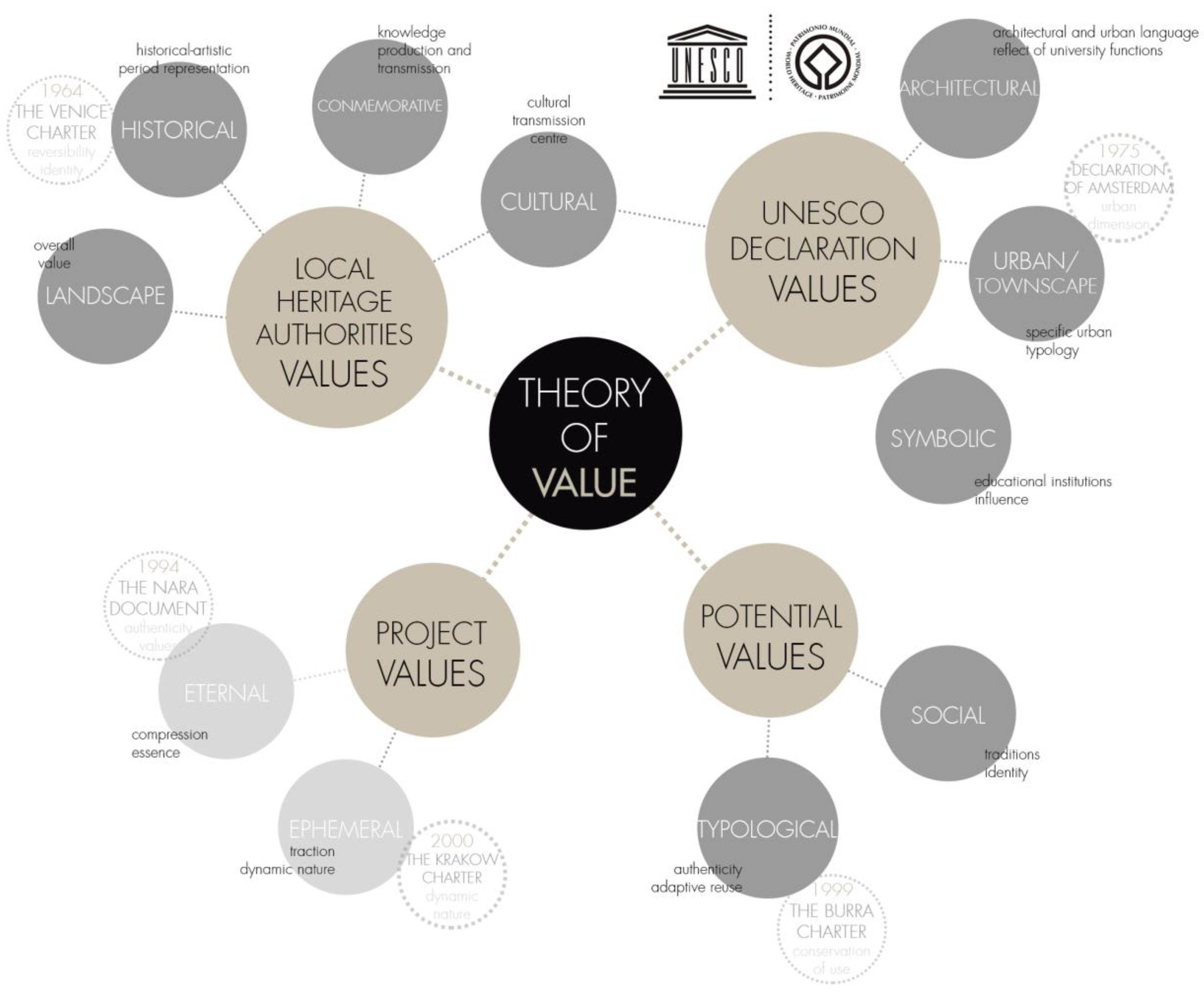

33]. This is why, in parallel to the definition of values, the intervention is introduced in the international framework of charters on built heritage intervention and adaptive reuse (

Figure 11).

Although we are aware of the difficulty involved in categorising the values of a heritage asset and the fact that this is an objective task, we will attempt to draw up a list of the cultural values present in TC.

For this purpose, they have been grouped into four main clusters. The Outstanding Universal Values recognised in the WH declaration will be accompanied by other cultural values, present both before and after the intervention project. The aim is to clarify which values are the initial ones, which ones are activated during the intervention, and which ones are enhanced and generated after intervention. They are related to the criteria of the declaration of the UC as a WH Site, as this declaration was made in parallel to the project process, as well as to the International Charters mentioned in the previous section (

Figure 11), with the aim of gaining a general vision of the intervention within an international context of the theory of value.

6.1. Local Heritage Authorities’ Values

The first group of values is related to the elements that local heritage authorities took into account to preserve Trinity College as part of the Paço das Escola ensemble.

HISTORICAL VALUE [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. This is an inexorable value for TC, as it tells part of the history of the UC, of the city and even of the building’s journey through the different artistic styles that have existed throughout its lifetime. This building is a key element in the re-foundation of the UC and in its development up to the present day, as this building, with its changes in use and slight modifications, has witnessed the evolution of the city, its university and the Order of the Holy Trinity.

In the words of the architects, this project has always sought reversibility in its nature. Their intention was to add a new layer to this palimpsest. It is an intervention in which at all times special attention and consideration is given to each of the building’s temporal layers, as well as its artistic expression, trying to maintain the monument’s identity. There is an attempt to maintain this identity regardless of whether it is a great work or a more modest one, since “the concept of a historic monument embraces not only the singular architectural work but also the urban or rural setting in which is found the evidence of a particular civilization, a significant development or a historic event. This applies not only to great works of art but also to more modest works of the past which have acquired cultural significance with the passage of time” [

47].

CONMEMORATIVE VALUE [

34,

46]. The building continues to serve a purpose that seeks to transcend time, as it did in its original use for university purposes. Moreover, as far as the commemorative value itself is concerned, it represents a complex of buildings which have been linked to knowledge production and transmission, which is also a

CULTURAL VALUE [

36,

38,

39,

44,

48,

49].

LANDSCAPE VALUE [

39,

44,

46]. This is a potential value in that this landscape appears as the contemporary medium or setting in which the life of the building elapses. It is a framework that sees the historic urban landscape as the result of a stratification which over the years has led to a series of cultural and natural attributes and values that transcend the idea of the urban centre as such.

6.2. UNESCO Values

Secondly, the UNESCO values are those embodied by the attributes that justify the selection criteria set out by the UNESCO commission in the Coimbra Declaration:

ARCHITECTURAL/AESTHETICAL VALUE [

4,

37,

38,

39,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

50]. Coimbra University buildings represent the development of an institutional and architectural design related to their use. TC constituted an innovative typology which later was replicated in other cities, as a building that served its purpose.

URBAN/TOWNSCAPE VALUE [

39,

44]. The University of Coimbra and its buildings represent a specific urban typology which demonstrates the integration between a city and its university. In fact, two different urban models were developed in parallel to the UC’s growth. With the understanding that “the architectural heritage includes not only individual buildings of exceptional quality and their surroundings, but also all areas of towns and villages of historic or cultural interest” [

51], Aires Mateus’ intervention shows an unquestionable urban vocation in its formal approach. This means that it is a highly sensitive project in terms of its integration into the

historic urban landscape in which it is inserted [

52].

SYMBOLIC VALUE [

37,

38,

39,

40,

44,

45,

46,

53]. In Coimbra, it is possible to recognise the city’s architectural and urban language linked to the institutional functions of the university, thereby presenting a close interaction between the two elements. This feature has also been understood as a recognition element in the city.

6.3. Project Values

Thirdly, and in terms of the project process, for Aires Mateus, the starting point of the project was the concept of the passage of time, as the marks left by it already formed part of its identity. The state of ruin of the complex was the result of a process of natural selection. This is why they delved into the theory of value, listing in their project a series of pre-existing values that “are visible to the naked eye, but are above all constructive”, and which are in turn activated by the intervention [

26]. These values, as stated by the architects, are as follows:

ETERNAL VALUE [

54]. Value is placed on the attributes that carry implicit eternity in their significance. This is embodied through the heavy and enduring elements of the construction: the load-bearing elements such as walls, arches and vaults. According to the architects’ assessment, these are the elements that encapsulate the character of the building, those that the passage of time has decided to preserve and which they, its mere servants, maintain and integrate into a proposal aimed at revitalising the college with the inclusion of a contemporary language.

This seems to be the initial objective of Aires Mateus in the intervention on TC: to determine what has eternal value and what has ephemeral value in the monument, basing their intervention strategy on this judgement of values. In spite of this, all dimensions of heritage need to be addressed when intervening—artistic, historical, social and scientific—to ensure preservation of its authenticity [

27]. In this regard, this intervention seems to justify itself only through tangible aspects, while failing to specify what its intangible scope is.

EPHEMERAL VALUE [

54]. This value highlights the changing or ephemeral capacity of the building as opposed to notions of massiveness or permanence. It is embodied by construction elements that have gradually faded over time. These were the wooden elements, those that functioned by traction, and which at the time of the intervention were no longer standing. These ephemeral elements were replaced by other elements with the same characteristics so that, over time, the monument would not lose its dynamic, changing and evolving character while still retaining the attributes that embody its inherent values. They position themselves in this changing condition of heritage, affirming the notion that “heritage cannot be defined in a univocal and stable way. It can only indicate the direction in which it can be identified” [

55].

6.4. Potential Values

Potential values are those that arise in relation to the current life of the monument and its capacity to evolve, i.e., the building is viewed considering its potential values, which the Aires Mateus intervention enhances and increases. These are dynamic and constantly evolving values, the fruits of the passage of time, which generate processes of enhancement and

added value, generating an evolving image of the monument in terms of its relationship with the city [

56].

SOCIAL VALUE [

4,

37,

38,

39,

42,

44,

46,

50]. The fact that a university has a series of traditions and events inherited from its past is undeniable, but this fact is even more powerful in the UC, the oldest university in the country. Moreover, these buildings respond to social issues of expansion and cultural distribution; that is, they represent a value that generates identity, with which the population identifies itself, as is the case of TC. Following the architectural intervention, the building provided the city and its inhabitants with different spaces for social and cultural encounters for both the university and local population.

TYPOLOGICAL VALUE [

45]. The definition of this value can be linked to the concept of architectural typology. It should be emphasised that at the time construction on TC began, when the UC was re-founded, there were no references for this type of building in the city or the country. As a result, it emerged as a new typology, to respond to a new need: a hybrid teaching–residential usage programme. It is a building with three main spaces: the church, the cloister and the dormitory, with the greatest potential lying in the voids generated between them, which respond to a common urban logic. The spaces generated in this typology now allow for readaptation, seeking the continued use of a heritage asset as one of the most effective ways of conserving it. The proposal for the reappropriation of spaces expressed by Aires Mateus seems key to preserving the vocation and nature of use of each of these spaces [

4].

Finally, in light of the current debate on high-quality

Baukultur inbuilt heritage intervention, the action in the case study is understood as a whole that is embedded within its environment [

57]. Rigour requires we ascertain whether this case of adaptive reuse squares with the balance between design and construction and cultural or social aspects, etc. Along these lines, in its concept, this intervention endeavours to become integrated into the environment, striving for a joint image of the city as opposed to a search for significance. Furthermore, it is aligned with this task, in that it seeks the preservation of cultural values as opposed to economic benefits. Despite this, the cultural assessment conducted in the intervention focuses solely on tangible aspects for maintenance of the monument’s identity, by opting for a reversible intervention. Yet this assessment process overlooks aspects intrinsic to the intangible heritage asset, such as its social or cultural significance, which transcend the reversible nature of the intervention.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

Throughout this article, we have expounded on the question of value in the project process of a contemporary heritage intervention, especially in a listed building, and therefore restrictive heritage requirements had to be met. This is an arduous task in the process of critical analysis of this type of action, as well as a necessary one. Evidently, this is a complicated but essential process. Notwithstanding the existence of theories that see the approach to interventions through values as a

dissatisfaction with the present, in search of a past

identity [

10], the definition of values is inherent in the project process. Despite the changing condition of the values of a monument, and the supposed subjectivity under which the process of cultural assessment of a heritage asset may be conducted, the values-based approach is a rigorous procedure for acting on an asset in order to maintain its

identity and

authenticity. For all the difficulties in categorising or grouping these values, it is an effort that must be made throughout the whole process of intervention on a heritage asset.

Therefore, the dialogue of heritage methodology with this type of architectural practice is an example that can be extrapolated to other instances of heritage rehabilitation. Insertion in the theory of value and an international context of heritage intervention enriches this process. This is why, from the research carried out in this article, the materialization of this dialogue process is taking shape through a new methodology for heritage intervention, which ensures a rigorous action that respects the identity and authenticity of the heritage asset via the identification and preservation of values throughout the process (

Figure 12).

Therefore, this study proposes a sequence of actions to be carried out on the analysis of heritage intervention: framing, documenting, acting and contrasting are part of a cyclical process which contextualises, characterises and documents the layers of the heritage asset, including its contemporary intervention. Transversal to the application of these actions is that of assessing, which runs through the whole process, within the framework of the theory of value. This procedure tries to bridge the gap between heritage studies and architectural practices by monitoring cultural values, which evolve constantly.

This research opens up a path for the discipline of architecture when dealing with contexts of a special heritage nature, which are subject to restrictive intervention requirements. Conservation as an attitude towards heritage is presented as an alternative, favouring a better and greater consideration of the context, transcending the physical in order to cater for the cultural. Decisions based on values permeate typical conservation processes [

3]. In this way, the creative role and architectural responses are reformulated, and the generation of form goes further, seeking to promote new spatial relationships in which the perception of the spectator-actor is especially relevant.

An example of this is the dialogue between the techniques of heritage studies and the Colégio da Trindade rehabilitation. It is possible to see how the presence of heritage assessment throughout the project process has made possible a quality architecture, capable of responding to heritage regulations while achieving an action that is inserted in an urban logic and that respects and enhances its heritage values.

Finally, and as has already been pointed out, this research paper is part of a broader scope, and therefore some aspects of the intervention in question have not been referred to in this article, but should be considered in the development of the research as a whole, such as the social and participatory component, which are inherent aspects of this kind of heritage. Here, Latour’s proposal to define objects in their hybrid condition within a scenographic context—

quasi-objects/

quasi-subjects—is transferred so as to reinforce the definition of heritage based on things material and immaterial, where what matters more than their own significance are the relations generated. Such a context is defined through the network of actors who are no longer observers, considering the role of objects as inserted in a kind of “parliament of things”. A democratic situation of possible relations between objects in which relations/actions can take place in a field of balances [

58].

Moreover, there is an open avenue for research on this topic, with the need to further align heritage studies and architectural intervention practices in order to ensure the quality of the results of interventions on heritage environments by identifying values. This offers an alternative for architecture when intervening in heritage contexts, based on conservation as a project tool that works by placing values at the centre of the debate. The identification of values must go beyond classification working the argumentative style, improving the description of the characteristics and the main aspects to be preserved in each project and process of managing values.