A Conservation Strategy for the Sanatorio Carlos Duran Cartín in Costa Rica

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials

2.1. Historical Background

2.2. Current Condition

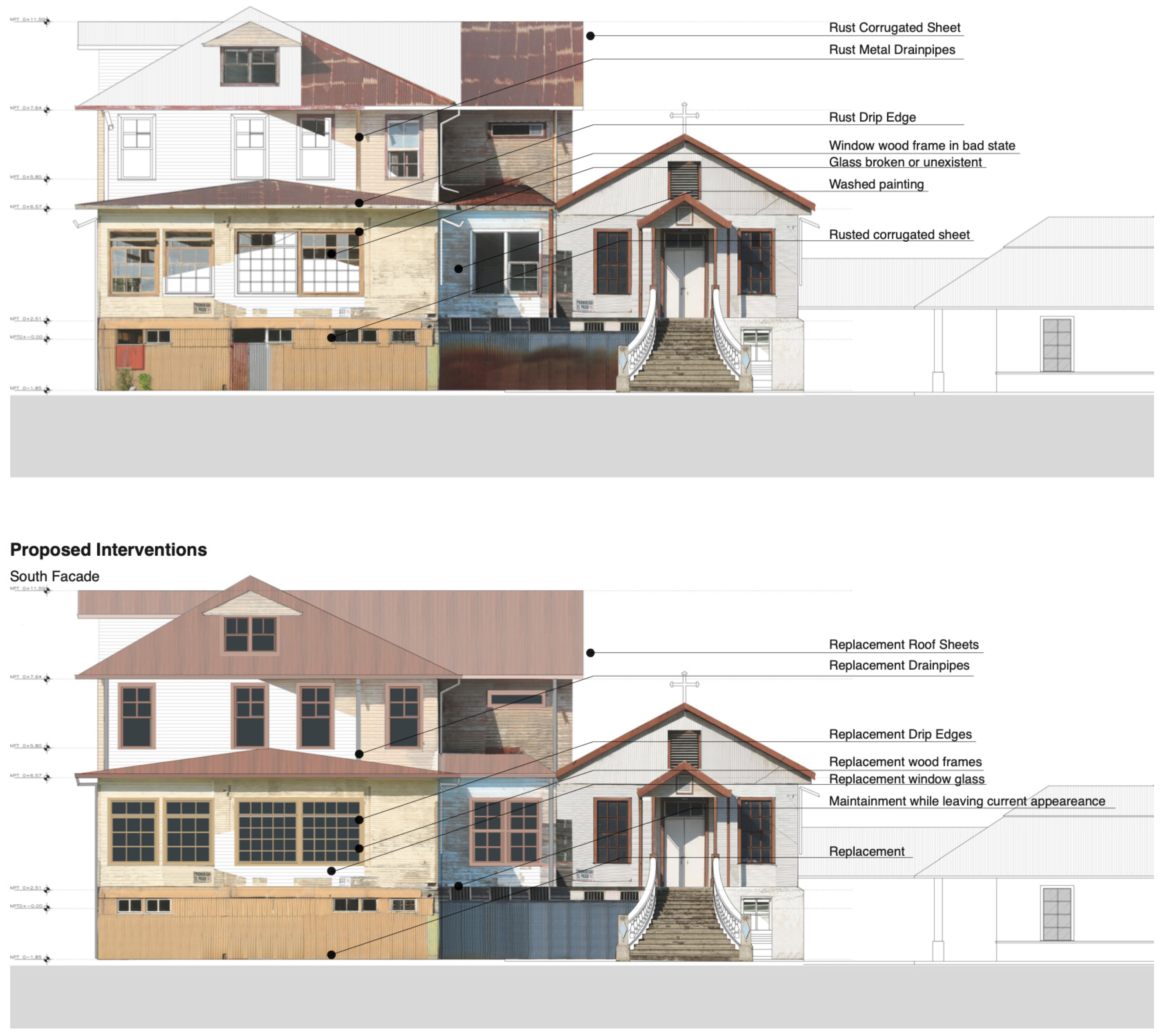

- The Administration Building, the only survivor from the original 1915 construction, stands in a state of severe decay, inaccessible to the public due to structural instability. It has been closed to preserve its integrity, with its front corridor and atrium demolished at some point in recent years. The exterior paint has faded, revealing multiple layers, while the wood shows signs of extensive wear. Windows are shattered or missing, with some openings covered by steel or aluminum sheets. Poor drainage has led to water leakage inside, damaging interior spaces;

- Among the buildings erected between 1918 and 1937, the Church, originally serving as a dining area, remains well-preserved and open to visitors. Since undergoing restoration, the kitchen and dining hall are in excellent condition. Similarly, the Women and Children Pavilion stands intact, displaying robust structural integrity and offering public access. Although the gym and recreational areas have been removed, the overall condition of the building is quite good. Some exterior paint may require attention, yet the original white color is still conserved with some signs of humidity. A few window openings have been sealed with concrete, and certain interior spaces are either locked or cluttered with garbage;

- Lastly, among the structures erected after 1937, the Women Pensioner Building stands in good condition. Closed to the public early on during the complex’s abandonment, it has maintained its integrity. Similarly, the doctor’s house remains intact, although signs of structural wear and deterioration are apparent in both the building’s structure and exterior facade details.

3. Methods

4. Results

4.1. Evaluation

4.1.1. Tangible Values

4.1.2. Intangible Values

4.2. Problematic Issues

4.2.1. Tangible Issues

4.2.2. Intangible Issues

Restoration and Possible Loss of Interest in the Place

Stigmatization and Collective Perception of the Architectural Complex

Complex Legal Framework

Financial Maintenance and Lack of Investment

4.2.3. Design Obsolescence

5. Discussion

Conservation Strategy

- Understand the place: Define the place and its extent, and investigate the place, its history, use, associations, and fabric;

- Assess cultural significance: Assess all values using relevant criteria, and develop a statement of significance;

- Identify all factors and issues: Identify obligations arising from significance, and identify future needs, resources, opportunities, constraints, and conditions;

- Develop policy;

- Prepare a management plan: Define priorities, resources, responsibilities, and timing;

- Implement the management plan.

- Stop further deterioration of the complex while trying to keep as much as possible of the current appearance of the buildings;

- Structurally reinforce the Administration Building, enabling the reintroduction of functional programming consistent with its original purpose, all while preserving the essence of its historical evolution;

- Incorporate newly designed elements as reminiscent of the original design while respecting the established charters;

- Comply with Costa Rican law 7600 of Universal accessibility in the whole complex;

- Address mechanical and electrical problems, and propose a fire protection system;

- To enhance both current and original values, educational and diffusion strategies will be incorporated, aimed at showcasing the site’s historical significance and fostering a deeper understanding of its role in innovation and knowledge development;

- Keep the self-sustaining condition of the sanatorium and provide the place of new tools and spaces for the generation of income, as suggested by step 5 of the Burra Charter;

- Explore ways to attract external funding for future conservation projects.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AUSTRALIA ICOMOS. The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance: The Burra Charter; ICOMOS: Burwood, NSW, Australia, 2013; Available online: https://australia.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Burra-Charter-2013-Adopted-31.10.2013.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Gutiérrez Viñuales, R. La conservacion y el patrimonio en America Latina: Algunos temas de debate. Visualidades 2012, 7, 183–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1972; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/convention-en.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Colomina, B. X-ray Architecture, 1st ed.; Lars Müller Publishers: Zürich, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas Coll, A. Los sanatorios antituberculosos chilenos como testimonio del vínculo entre arquitectura, salud e higiene (1902–1940). Ph.D. Thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Curto, D. Il patrimonio della montagna disincantata. Tutela e riuso dei sanatori nelle Alpi. In Alpi e Architettura. Patrimonio, Progetto, Sviluppo Locale, 1st ed.; Del Curto, D., Dini, R., Menini, G., Eds.; Mim Edizioni: Sesto San Giovanni, Italy, 2016; pp. 147–167. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Principles for the Analysis, Conservation and Structural Restoration of Architectural Heritage. In Proceedings of the ICOMOS 14th General Assembly, Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, 27–31 October 2003; Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/about-the-centre/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/165-icomos-charter-principles-for-the-analysis-conservation-and-structural-restoration-of-architectural-heritage (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention; WHC.05/2; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2005; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/opguide05-en.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Gómez Vargas, S.; Vives Luque, I. Edición Especial: Sanatorio Duran. Revista del Centro de Investigación y Conservación del Patrimonio Cultura, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Velazquez Bonilla, C. Tierra Blanca Una Montaña de Esperanza En La Cura de La Tuberculosis. Diálogos Rev. Electrónica 2008, 9, 282–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, C.; Picado, T.; Fernandez, L.; González Rucavado, C.; Jimenez, L.P. Sanatorio Carit Para Tuberculosos. Cartago, Costa Rica, 1st ed.; Biblioteca Nacional de Salud y Seguridad Social BINASS: Costa Rica, 1918; Available online: https://www.binasss.sa.cr/revistas/hospitales/1918A.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Solís Barquero, G. El Dr. Carlos Durán C: Su Participación en la Política Costarricense. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de Costa Rica, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, P. The Evolution of the Sanatorium: The First Half-Century, 1854–1904. Can. Bull. Med. Hist. 2006, 23, 457–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Vives Luque, I. Pioneros de La Arquitectura Moderna En Costa Rica, 2nd ed.; Colegio Federado de Ingenieros y de Arquitectos: San Jose, Costa Rica, 2018; ISBN 978-9968-933-11-7. [Google Scholar]

- Carrington, T.S. Tuberculosis Hospital and Sanatorium Construction, 1st ed.; National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis: Northborough, MA, USA; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1911; Available online: https://books.google.it/books?id=1EArAAAAYAAJ (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- 16. El Presidente de la Republica; El Ministro de Cultura y Juventud. Declaratoria Sanatorio, Costa Rica, 2014; Volume N° 223.

- ICOMOS. Approaches for the Conservation of Twentieth-Century Cultural Heritage; ICOMOS: NewDelhi, India, 2017; Available online: https://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/2688/ (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Campbell, M. What Tuberculosis Did for Modernism: The Influence of a Curative Environment on Modernist Design and Architecture. Med. Hist. 2005, 49, 463–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbonetti, A. Historia de La Tuberculosis En América Latina. A Modo de Introducción. Estud. Digit. 2012, 11–16. Available online: https://revistas.unc.edu.ar/index.php/restudios/article/view/2547 (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Armus, D. La Ciudad Impura: Salud, Tuberculosis y Cultura En Buenos Aires, 1870–1950, 1st ed.; Edhasa: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2007; Available online: https://books.google.it/books?id=-ylgAAAAMAAJ (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Lourenco, P.B. The ICOMOS Methodology for Conservation of Cultural Heritage Buildings: Concepts, Research and Application to Case Studies. In Proceedings of the Conference REHAB 2014—International Conference on Preservation, Maintenance and Rehabilitation of Historical Buildings and Structures, Tomar, Portugal, 19–21 March 2014; p. 954. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269048243_The_ICOMOS_methodology_for_conservation_of_cultural_heritage_buildings_Concepts_research_and_application_to_case_studies (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Velázquez Bonilla, C. El doctor Carlos Durán. Su investigación médica y sus estudios sobre la niñez. Diálogos. Rev. Electrónica Hist. 2006, 7, 80–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias Quirós, A.C.; Arrea Siermann, F.; Barquero Morice, P.; Mena Bustamante, F.M.; Rojas Madrigal, M. Lo cotidiano desde un centro de excelencia en salud: El caso del Sanatorio “Carlos Durán Cartín”, Cartago, Costa Rica. Una aproximación desde la arqueología histórica. Rev. Del Arch. Nac. 2012, 76, 43–52. Available online: https://www.dgan.go.cr/ran/index.php/RAN/article/view/129 (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Ruiloba Quecedo, C. Arquitectura Terapéutica: El Sanatorio Antituberculoso Pulmonar. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Valladolid, Valladolid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. The Nara Document on Authenticity; ICOMOS: Paris, Francia, 1994; Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/charters-and-texts/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/386-the-nara-document-on-authenticity-1994 (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Khalaf, R.W. World Heritage on the Move: Abandoning the Assessment of Authenticity to Meet the Challenges of the Twenty-First Century. Heritage 2021, 4, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AUSTRALIA ICOMOS. Practice Note: Understanding and Assessing Cultural Significance; ICOMOS: Burwood, NSW, Australia, 2013; Available online: https://australia.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/Practice-Note_Understanding-and-assessing-cultural-significance.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Holtorf, C. Conservation and Heritage as Future-Making. In A Contemporary Provocation: Reconstructions as Tools of Future-Making, Proceedings of the ICOMOS University Forum Workshop on Authenticity and Reconstructions, Paris, France, 13–15 March 2017; Holtorf, C., Kealy, L., Kono, T., Eds.; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2018; Available online: https://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/1857/1/6_Holtorf.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- COOPRENA R.L. Perfil de Inversión para la Oportunidad Turística Identificada en el Parque Nacional Volcan Irazú; SINAC: Costa Rica, 2014. Available online: https://www.sinac.go.cr/ES/transprncia/Planificacin%20y%20Gestin%20BID/Gesti%C3%B3n%20Sostenible%20del%20Turismo%20Sector%20Privado/Zona%20de%20Influencia%20PN%20Volc%C3%A1n%20Iraz%C3%BA/PERFIL%20DE%20INVERSI%C3%93N%20PNVI%20FINAL.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Barquero Morice, P. Jugando en el Sanatorio Durán: Entre la exclusión y la inclusión social. Rev. Herencia 2017, 30, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, S.; Jacobs, J. Buildings Must Die: A Perverse View of Architecture; Mit Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- La Asamblea Legislativa de la Republica de Costa Rica. Ley de Patrimonio Histórico Arquitectónico de Costa Rica 7555; Costa Rica, 1995; Volume N° 199, Available online: https://www.ucr.ac.cr/medios/documentos/2015/LEY-7555.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Espectro Canal UCR. Sanatorio Durán, Por Lillianne Sánchez (2015). 2016. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qZXABOaXWB4 (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Muñoz-Viñas, S. Contemporary Theory of Conservation. Contemp. Theory Conserv. 2012, 47, 1–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sibaja Matamoros, A.E.; Garzulino, A. A Conservation Strategy for the Sanatorio Carlos Duran Cartín in Costa Rica. Architecture 2024, 4, 342-366. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture4020020

Sibaja Matamoros AE, Garzulino A. A Conservation Strategy for the Sanatorio Carlos Duran Cartín in Costa Rica. Architecture. 2024; 4(2):342-366. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture4020020

Chicago/Turabian StyleSibaja Matamoros, Andrea Elena, and Andrea Garzulino. 2024. "A Conservation Strategy for the Sanatorio Carlos Duran Cartín in Costa Rica" Architecture 4, no. 2: 342-366. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture4020020

APA StyleSibaja Matamoros, A. E., & Garzulino, A. (2024). A Conservation Strategy for the Sanatorio Carlos Duran Cartín in Costa Rica. Architecture, 4(2), 342-366. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture4020020