1. Introduction

World Heritage Site (hereafter WHS) inscription has been considered a catalyst for cultural heritage tourism development worldwide [

1,

2,

3]. This is especially relevant in a Chinese context where the effect of WHS tourism can be clearly observed [

4,

5]. In transforming WHSs into tourism resources, the values and meanings of China’s WHSs are often defined by and safeguarded through the contested input of the government, heritage agencies, and the general public [

6]. However, tension between stakeholders can trigger displaced interpretations of heritage assets that require conservation methodologies to be constantly reappraised. Firstly, official Chinese mechanisms have attached political significance to WHS inscription by imposing pressure on heritage sites to maintain their material authenticity. Interpretative decision-making is commonly translated into strict monitoring systems and/or static heritage exhibitions. Secondly, WHSs have been widely utilized as catalysts for revenue over other social and cultural values [

4]. Such a tendency primarily leads to the proliferation of commercially constructed tourism programs, which triggers heritage representation methodologies.

The Classic Gardens of Suzhou falls within the intersection of these two associated yet somewhat contested discourses. Once certified as ‘authentic’, classic gardens are decontextualized and displayed as relics for inspection and appreciation by the visiting public [

7]. Consequently, the socio-cultural values of the gardens that support their designation as heritage tends to become obscured in the process of museumization. Efforts to catalyze the transformation of demarcated heritages into tourism resources, therefore, face challenging issues between traditional heritage conservation conflicting with the management of change to facilitate development processes [

8].

Drawing on the anxieties imposed by critical heritage theory (in terms of heritage conceptualization and representation), we explore the shifting conservation practice undertaken at one of the first Classical Gardens to be inscribed as a WHS garden in 1997—the Humble Administrator’s Garden (hereafter HAG) and its associated architecture (The Li Residence). This 16th century scholarly estate of the HAG is considered representative of the Classical Gardens, often portrayed as a physical manifestation of ‘scholar-official’ dominance across society, aesthetics, and building skills in imperial China [

9]. Yet within this article, we assert that this portrayal is also underpinned by an interpretation of the HAG as a symbol of unity between architecture and landscape [

10]. In reference to this, we explore how its conservation increasingly works towards nurturing a holistic narration of place, capturing both building and landscape within its conservation assessment and management. We further highlight how this fosters the communication of non-physical heritage (or ‘intangible heritage’) in the evolving conservation approach of the HAG.

2. Intangible Heritage and the Cultural Landscape

Since the middle of the 20th century, international heritage protection mechanisms developed by UNESCO and ICOMOS have been critiqued for their restricted conceptualization of heritage [

11] (p. 27), [

12] (p. 18), with their focus being placed primarily on physical art-historical manifestations of national identity [

13] (p. 18). The creation of the World Heritage Convention (hereafter WHC) [

14] was one of the first clear international moves towards a broader definition of cultural heritage, with the landscape being formally established as a definitive cultural heritage category [

15] (p. 39). This resulted in additional focus given to areas and places that contained ‘natural features’, ‘geological and physiographical formations’, and ‘natural sites’ [

14] (p. 2). Subsequently, this paved the way for more nuanced terminology and guidance in relation to landscape, such as Historic Gardens [

16], and eventually the term ‘cultural landscape’, which became formalized in the WHC in an early 1990s revision [

17] (p. 122). This expansion of cultural heritage can also be seen to track a broadening of alternative conservation ideologies [

18] (p. 7). Although the concept of cultural landscapes was conclusively integrated into world heritage terminology over thirty years ago, the general idea of natural heritage is still comparatively new to the concept of World Heritage [

19] (p. 159). This is despite the broader ideas and sentiments of natural landscape protection being ingrained within both the Romantic Movement and overarching Enlightenment philosophy [

13] (p. 21), [

18] (p. 3). Interestingly these are two key historical moments that assisted in defining the principles of what would become the modern conservation movement in the late 19th century.

Whilst heritage categories expanded, a sentiment of disapproval over a lack of representation within UNESCO’s worldview of heritage continued and reached a crescendo in the 1990s [

20] (p. 97), when UNESCO itself began to acknowledge the inherent precedence given to West European material heritage sites at the expense of ‘living’ cultural heritage. This awareness was buttressed by criticism from heritage scholars and non-Western UNESCO member states who lobbied for a more inclusive concept of World Heritage [

21] (p. 32). The Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage [

22]—commonly referred to as the Intangible Cultural Heritage Convention (hereafter ICHC)—is often regarded as an outcome of this lobbying, although the heritage value of cultural landscapes was given greater focus in the decade leading up to the production of the ICHC [

13] (p. 31).

Of particular interest to this contribution is the connection and synergy between heritage buildings, cultural landscapes, and intangible cultural heritage (hereafter ICH), with the use and evolution of cultural landscapes being actively transformed through the practices that are sustained by intangible heritage [

15] (p. 40). The ICHC hoped to offer a remedy for the unfair distribution of World Heritage [

23] (p. 964) by initiating an official definition of ICH (hereafter ICH) [

24] (p. 919). Formalized guidance for its safeguarding was also introduced, which avoided nomenclature typically used to describe the significance of tangible heritage [

25] (p. 75). UNESCO defines ICH within Article 2 of the 2003 Convention as

…the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills… that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage. This intangible cultural heritage… is constantly recreated by communities and groups in response to their environment, their interaction with nature and their history, and provides them with a sense of identity and continuity…

Lenzerini [

26] (p. 101) summarizes the key themes of the ICHC as self-identification; constant re-creation; identity; authenticity; and human rights. Thus, the convention is known for being constructed to address globalization through the support and celebration of cultural diversity [

22] (p. 1), [

27] (p. 265). Ironically, it is this creeping scope of what constitutes World Heritage that has also led to increasing control by states/governments over a much broader range of heritage typologies [

17] (p. 56). Indeed, from a tourist perspective, the convention could be utilized as a tool to misuse those very practices that it has been created to guard by raising local traditions onto global platforms [

28] (p. 78), [

29] (p. 731), [

30]. The potentially confusing result is that UNESCO becomes the creator of the very issue they are seeking to resolve through the production of the ICHC [

17] (p. 115), [

27] (p. 266).

3. A Holistic Understanding of ‘Place’

Increasing interest in an integrated understanding of World Heritage and intangible qualities of heritage is having an impact on how much cultural landscapes are acknowledged when considering the conservation of built heritage. There are two key reasons for this. Firstly, as ICH primarily concentrates on practices, the implication of this focus is an interest in the various types of landscapes where these practices take place [

17] (p. 115). Thus its impact has been to confront the “nature–culture split” that Hill [

31] describes as central to the construction of traditionally siloed heritage domains. Through the merger of natural and cultural concepts, the landscape is reconceptualized as heritage and subsequently entangled in the idea of ‘place’ alongside buildings, monuments, and other artifacts [

16] (p. 31), [

32]. Secondly, as the notion of heritage expands to incorporate new models of what heritage could be (landscape and historic gardens being examples of one such expansion route), any built heritage site appraisal/assessment must now take appropriate notice of the broader site and landscape within which it is contextualized (i.e., within a Heritage Impact Assessment at a World Heritage Site). This approach is most revealing within the Burra Charter’s practitioner guidance—in particular, their definition of places of cultural significance as being comprised of “…elements, objects, spaces and views… [and] may have tangible and intangible dimensions” [

32]. Therefore, when considering the physical conservation of built heritage fabric, professional decision-making will be influenced by a concern for the cultural heritage landscape in a more holistic and balanced sense than has previously been the case. For example, in a study concerning the Class II designated Hilton of Cadboll stone in Scotland, UK, Jones [

20] (p. 105) describes how a more integrative reading of the relationship between landscape, historical monuments, and people can holistically constitute ‘place’ and therefore blur the differentiation between building and landscape. However, where this remains problematic for many World Heritage Sites is how the landscape is often conceived as a backdrop or complementary addition to architectural and/or urban tangible heritage (for example, see [

33] (p. 63)).

In relation to this, it is worth re-visiting the now timeless statement by Laurajane Smith, which, whilst many use this to form critical positions with regards to the conservation of built heritage, can also be seen to have relevance to cultural heritage landscapes as well:

It is value and meaning that is the real subject of heritage preservation and management processes, and as such all heritage is ‘intangible’ whether these values or meanings are symbolized by a physical site, place, landscape or other physical representation…

When conceptually processed through the notion of ‘heritage’ as a reflexive present-day process [

34], landscapes become both cultural and mnemonic [

13] (p. 46), [

35] (p. 5). Pierre Nora’s term

milieux de memoir (environments of memory) reflects this, whereby a landscape becomes part of ongoing present-day interactions to create an active “memory culture” see [

36] (p. 27). Hence the emergence of terms that seek to add a cultural deposit to the term landscape—such as “memoryscape” [

37], “memorialscape” [

38], “deathscape” [

36] (p. 36), and so on. In considering the heritage value and meaning of a cultural heritage landscape, Smith [

13] (p. 56) asserts that conceptualizing heritage as “intangible” shifts concerns to that of heritage effect, which is the way spatial configurations and practices can move people in various ways (some examples given include emotionally, politically, and culturally). So even more than built heritage, cultural heritage landscapes can accommodate various contemporary interpretations of history and society, with many of these understandings often being in direct conflict with one another [

39] (p. 89), [

40] (p. 6). A cultural landscape can therefore be understood as culturally, experientially, and emotionally layered [

41] (p. 42), inclusive of the tangible heritage that is situated upon it.

4. Evolving from a Traditional to a Contemporary Conservation Approach

At the core of built heritage conservation is a quest for the representation of historical truth in physical remains that are deemed to be of value [

42] (p. 28). A traditional conservation approach typically achieves this through the communication of a prevailing narrative to the users of the heritage, and the concern for centuries has been how conservative or innovative one can be when considering how to communicate and/or represent this narrative. Conversely, a contemporary conservation approach—which is situated within the context of a postmodern heritage paradigm—must now evidence diversity and multi-vocality by demonstrating a steady evolution of significances (note the plural) that track contemporary values [

11] (p. 15), [

42] (p. 2). Whilst a cultural heritage landscape has the capacity to accommodate this notion of re-evaluation, built heritage is far more problematic—primarily because it is both philosophical and logistically rigid. Equally, as already touched upon, cultural heritage places must also now be malleable enough to represent and uphold a variety of oftentimes conflicting narratives, meaning different conservation methods may be required to represent different stories, and therefore heritage practitioners will likely require shifts in appraisal and management approaches to better reflect heritage as non-physical, processual, and dynamic [

43] (pp. 1110–1111). These shifts that are required will not only be related to the development of approaches that push beyond the classic binary of preservation and restoration but also to how traditional approaches are valued and viewed in contemporary society (for example, see Djabarouti [

44] (p. 122)). These differing approaches have been described as the ‘tautological argument’ of restoration [

18] (p. 208), where the history of the building must be rationalized against its present-day development, which paradoxically also becomes history itself via the passage of time. The question for built heritage practitioners is, therefore, whether one should utilize a conservation method that can venerate a particular moment in time or should a multiplicity of times and stages of development be conserved [

45] (p. 4).

When considering world heritage in the more holistic sense (landscape, built form, and the cultural practices that shape them), this question becomes even more obscured, which serves to demonstrate how contemporary understandings of heritage are moving faster than the conservation appraisal and management approaches that practitioners employ. Hence why international heritage sites that capture both landscape (dynamic) and building (static), as well as representations of both tangible (physical) and intangible (non-physical) heritage, such as the HAG, serve as useful cases for exploring this interplay between building and landscape in more detail and through a heritage- and place-specific lens. Furthermore, as the heritage scope broadens to consider this interplay, conservation concerns of a more performative nature emerge in terms of how a place can support society to reproduce commemorative ceremonies, bodily practices, and other everyday practices through social performance [

46] (p. 23), [

47] (p. 10).

5. Materials and Methods

The scope of our case study exploration primarily concerns two aspects. Firstly, addressing the physical and cultural divisions of architecture and landscape within the HAG influences its integrity as a WHS and the sustainability of its changing socio-cultural significance. Secondly, exploring the experimental narrative development process that now foregrounds previously silent heritage stakeholders. We assert that the transitioning interplay between the government, conservation practitioners, and the public in representing this WHS is reflective of the changing perception of heritage in a Chinese context, which is inherently linked to a globalized critical re-evaluation of how heritage is conceptualized.

The case of the HAG is explored via a mixed methodological approach. Case study data was obtained from archival research. Policy papers, reports, and conservation records of the HAG since the 1940s were accessed through public archives and the HAG Management Office. We then conducted semi-structured interviews with the HAG Management Office between February and April 2023. Each interview lasted between 40–90 min to allow in-depth discussions that revolved around three themes: the HAG’s responses to WHS conservation policy; the interviewee’s role in intervention; and the identification of involved actors in the HAG representation process. In addition, we also reviewed 52 visitor journals that were collected between March and May 2023. This offers a set of triangulated data sources, the benefit of which being to not only verify the data [

48] but, more specifically for this case, to ensure that differing (and possibly opposing) views are consolidated into the study findings in relation to the interplay between the buildings and landscapes on the site [

49] (p. 81). Visitor journals accessed through the HAG Management Office were anonymized upon collection.

6. Case Study: (Re)Conceptualizing the Humble Administrator’s Garden

6.1. Overview

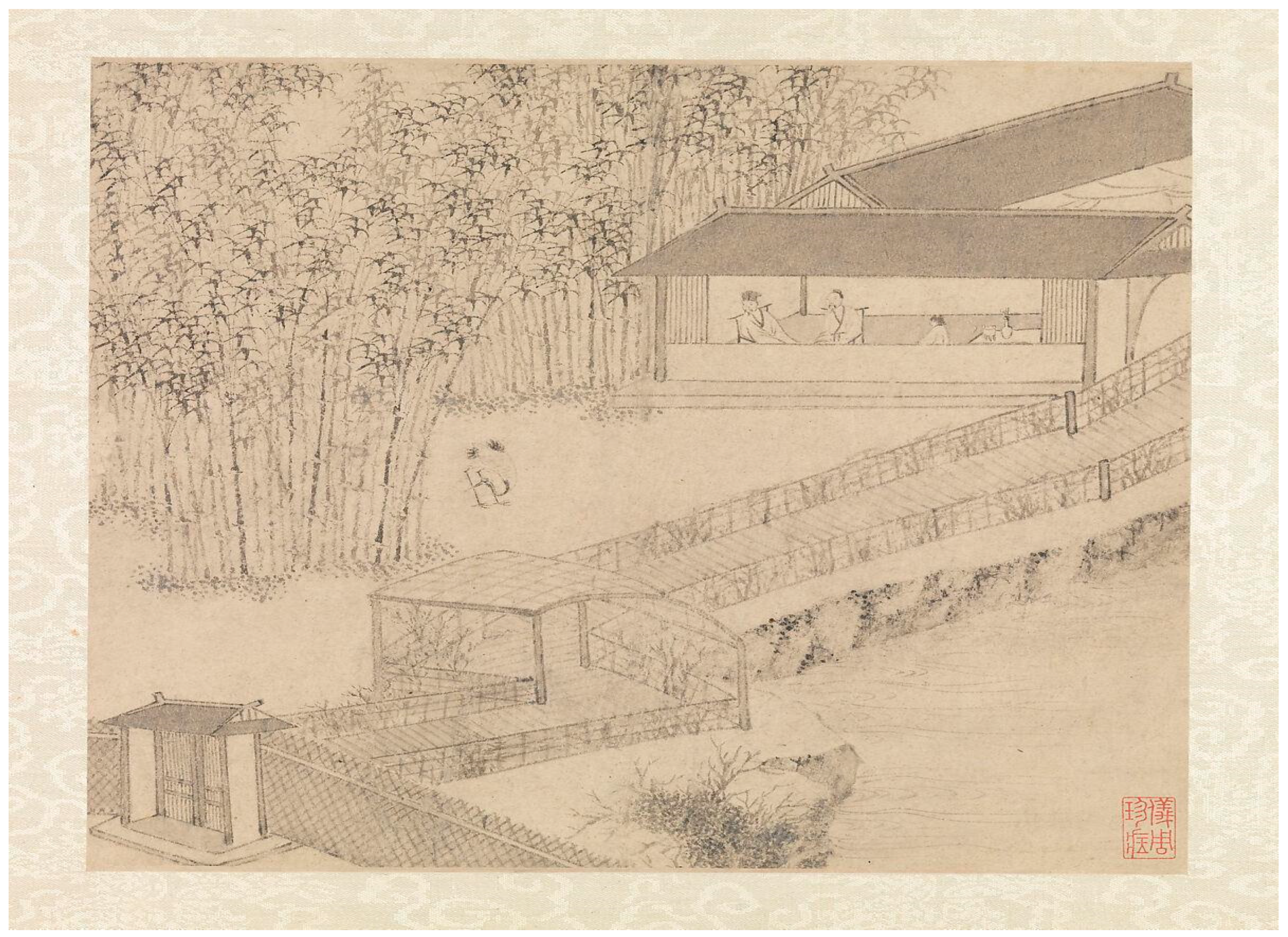

The culturally and socially significant HAG is considered a representative of the Classic Garden of Suzhou and was among the first to be inscribed as a WHS garden in 1997. Completed at the peak of imperial China, the estate is conceptualized by both a prevailing scholar-official culture in China’s East Yangtze Delta region and an aesthetic of traditional Chinese landscape painting. It conveyed the most esteemed pursuits of contemporary Chinese society, such as the joie de vivre of home (architecture) being closely integrated with nature (landscape) and social status being achieved through the attainment of a political career (

Figure 1). The housing complexes situated at the southern end of the site are representative of typical Suzhou residential architecture, whilst, in the north, the significance given to the garden results in a water-based naturalistic landscape that is embellished by buildings. In this study, the HAG is considered a symbol of unity between architecture and landscape [

10]. Within this context, this contribution focuses on exploring the blurred boundary between architecture and landscape to illustrate how the HAG fosters a holistic narration of place, capturing both building and landscape within its conservation processes.

Architecture, therefore, serves as the key medium through which place-making is not only about the physical manifestation of space but also about the ideology and culture that underpins it. UNESCO’s synthesis of the Classic Garden of Suzhou’s Outstanding Universal Value (hereafter OUV) reminds us acutely of the significance of this holistic approach. This has implications that extend beyond academic discussion to encompass long-term conservation strategies that are inclined heavily toward landscape:

… These garden ensembles of buildings, rock formations, calligraphy, furniture, and decorative artistic pieces serve as showcases of the paramount artistic achievements of the East Yangtze Delta region; they are in essence the embodiment of the connotations of traditional Chinese culture.

Criterion (iv): The classical gardens of Suzhou are the most vivid specimens of the culture expressed in landscape garden design from the East Yangtze Delta region in the 11th to 19th centuries. The underlying philosophy, literature, art, and craftsmanship shown in the architecture, gardening as well as the handcrafts reflect the monumental achievements of the social, cultural, scientific, and technological developments of this period.

Criterion (v): These classical Suzhou gardens are outstanding examples of the harmonious relationship achieved between traditional Chinese residences and artfully contrived nature. They showcase the lifestyle, etiquette and customs of the East Yangtze Delta region during the 11th to 19th centuries.

Our investigation of the HAG, therefore, begins first with understanding the impact of a transformational conservation approach in supporting the notion of unifying architecture and landscape. To explore this in more detail, a more specific focus will be placed on the HAG’s architecture complex, namely, the Li Residence, and its transition from a static exhibit to a space of cultural encounter. The Li Residence is the HAG’s sole remaining housing complex that consists of a series of typical East Yangtze Delta timber-framed, multi-storey dwellings, with its plan distributed along two north–south parallel axes.

6.2. The Divided Garden

Over the past five centuries, the HAG has undergone multiple changes of ownership that have led to significant alterations to its physical fabric. The current appearance of the HAG dates from the late Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), during which time the housing complexes towards the south of the garden were divided into three parts. These were known as, in order from east to west: the Li Residence; the Residence of Prince Loyal; and the Zhang Residence. Each of these three complexes covers an area of approximately 2400 square meters, 7700 square meters, and 8000 square meters, respectively (

Figure 2).

Today it is almost impossible to trace with certainty whether the HAG’s form in the late Qing was highly consistent with that of the 16th century due to the lack of historical plans. However, significant alterations seem likely based on the surviving records that indicate a continuous renewal of the architecture and landscape over the centuries. Renovations between the 19th and 20th centuries focused on the addition of ornamental garden buildings and the expansion of housing complexes, including the complex to the southwest of the garden that was later known as the Zhang Residence. The series of alterations that were made to the HAG, transforming both its housing complexes and the garden, were perceived as exclusively sympathetic to the owners’ cultural interests, leading to public scrutiny. Thus, this process—rather than detracting from the HAG’s socio-cultural significance—resultingly contributed to the public appreciation of scholar-official place-making activities. Through this, the HAG has continued to convey the aesthetic and lifestyle interests of the scholar-officials that influenced the architectural culture of the entire East Yangtze Delta region. Under this premise, the changing HAG remained authentic, although in a way that differs from the authenticity defined in Western conservation ideologies. The HAG’s residential complexes were repurposed for various functions in the early communist era (1940s–1950s), which arguably led to a dramatic transition of its historical socio-cultural meanings. Whilst the Residence of Prince Loyal became an independent historical display building from the 1960s onwards, the Zhang Residence was repurposed for multiple municipal functions in succession, leading to its demolition in 2003 after decades-long deterioration. The site was later requisitioned for the development of Suzhou Museum, designed by architect I.M. Pei and opened in 2007. The Li Residence, on the other hand, was reformed to accommodate a local art school until the late 1980s. Corresponding to this is the reform of the historic private gardens prompted by strong contemporary socialist thinking, resulting in the HAG being opened to the public as an urban park in the 1950s. This conveyed a clear message from the local authority: the once scholarly landscape now belongs to the masses. The HAG’s previously integrated housing complexes and garden, in addition to being spatially divided, were given different functions respectively: the architecture was now to symbolize the mundane life of ordinary people, while the landscape was to serve as a contemporary public urban resource. The notion of a unity existing between architecture and landscape that once existed in the overarching scholar-official dominated narrative consequently ceased to exist.

7. Results

7.1. Restoring a Historical Unity

Whilst the primary scope of this paper revolves around an exploration of the HAG’s historical evolution, it is also our intention to demonstrate how this process has led to a very predictable approach toward conservation methods and practice. Records from the HAG Management Office suggest approximately 1.2 million RMB of investment in the HAG’s physical restoration at the end of the 20th century, which was concerned with ensuring the spatial form of both architecture and landscape was faithfully restored. Of the three complexes that once existed in the south of the HAG, only the Li Residence remains intact to this day. The WHS inscribed HAG as a unified housing complex and garden that covers an area of 52,000 square meters. The conservation of its housing complex (i.e., the Li Residence), however, contrasts markedly with that of the landscape. Between 1992 and 2007, the Li Residence was opened to the public as the first garden museum in China. Static displays were curated with the aim of communicating the values of the HAG through associative objects, with the architecture acting as the backdrop. The built heritage, in a rather literal sense, was museumized.

The caution in approaching material authenticity as the primary conservation focus is increasingly evident in the Li Residence’s systematic restoration between 2009 and 2014, arguably to further align with UNESCO’s framework of authenticity. Traditional conservation and construction techniques were applied in addition to reusing a considerable amount of original building material (anastylosis), which was supported by the involvement of traditional local craftspeople [

50]. Yet despite its architectural restoration, the HAG continues to prioritize the garden as its main tourist resource. Upon its reopening in 2014, the now materially authentic Li Residence was repurposed from a museum gallery to the primary exit from the garden. It has since served as a residential showcase space for the HAG. This is primarily due to the Li Residence’s limited capacity, with peak tourism traffic in the HAG reaching up to 9000 people per hour. The practice of utilizing a heritage building as a garden exit has legitimized an approach towards the Classical Gardens of Suzhou, with similar considerations being shared among other Classical Gardens. The built heritage that is intimately entangled with the history of the garden has been transformed from a space of encounter to a space of transit, where only unmeaningful experiences are likely to be accommodated at the end of the tours that take place in the gardens. The HAG’s Management Office attempted to revive this fading sense of unity between architecture and landscape by embedding an immersive multimedia tour that was developed in 2020. This night tour program forms part of the Suzhou government’s municipal strategy to restore the local economy in a post-COVID time. Here we have attempted to summarize the immersive multimedia tour—if not over-simplify it—as our focus is not the tour per se but the collaborative yet contested heritage commercialization process that it engenders.

Upon entering the Li Residence on the south end of the HAG, one’s spatial movement follows a narrated route. The notion of walking is guided and framed along the central axis northwards until entering the garden. Throughout this experience, the route restores the HAG’s historical spatial form of a house at the front and a garden at the back. The tour then continues and unfolds around the water body (

Figure 3).

Reimagined intangible heritage—in this case, literati aesthetics, activities, and feelings that tie together the HAG’s buildings and landscape, is translated into scenes. A total of eight scenes are designed within the Li Residence and fifteen in the garden, respectively. This description is perhaps somewhat paradoxical as the sense of rigid division between architecture and landscape is diluted in the tour. This is represented by, for instance, the imitations of scholarly activities that are centered around the notion of viewing. Building components—including walls, beams, and decorative elements—are used as part of the display to facilitate immersive multimedia experiences that depict garden life scenes (

Figure 4).

The Li Residence’s otherwise obscured function that extends beyond living is hereby unfolded. Through this, architecture is (re)portrayed as the agency between people and the environment. As one visitor’s journal remarked:

I have visited (the HAG) before but this is a different experience. I suppose there is an aesthetic conception that’s communicated through the scenes and the narrated tour.

(VJ 6)

7.2. The Heritage Narrators

It is important first to acknowledge that the primary purpose of the HAG Management Office’s participation in developing the immersive multimedia tour is to reinforce state control of heritage resources whilst maximizing local economic benefits [

6]. The management of the Classical Gardens in Suzhou has fallen within the jurisdiction of the Suzhou Garden Management Office since its establishment in the early communist era. Affairs, including conservation and heritage commodification, were henceforth considered governmental matters. The role of conservation practitioners in negotiating the contested heritage value, tourism profits, and local policies remains relatively vague. It is also worth noting that the HAG is by no means the first heritage asset to embark on an attempt at performance tourism. Local WHS gardens have successful histories of manufacturing and simulating historical East Yangtze Delta region culture and scholar-official lifestyle to enhance tourist attraction. To give an example, the Master of Nets Garden, which was inscribed on the World Heritage List (hereafter WHL) in 1997, continues to accommodate night-time Kun Qu Opera performances in its garden. The major theatrical form of Kun Qu Opera was locally rooted (14th to 17th century) and was inscribed as ICH in 2021. Although there is no evident connection between the design and construction of the Master of Nets Garden and Kun Qu Opera, the program has been well received for (re)creating a garden life scene. Its long-lasting success has created a paradigm for Suzhou’s WHS gardens. Both the Lion Forest Garden and the Canglang Pavilion, inscribed on the WHL in 1997 and 2000, respectively, have also applied a similar strategy. The immersive Kun Qu Opera performance in the Canglang Pavilion, for instance, is adapted from the life events of garden owners in the 19th century. The priority of the visitor experience is a purposefully designed narrative experience rather than simply the visual appreciation of physical heritage fabric (

Figure 5).

Whilst performance tourism in a series of WHS gardens has proven successful in generating economic profit, the HAG Management Office had only established the immersive multimedia tour in 2020 as a response to the local authority’s post-COVID economy recovery plan. A local tourism entrepreneur was entrusted to operate the HAG’s immersive multimedia tour upon its creation in 2020, of which a 20 million RMB (approx. 3 million USD) investment was made. In 2021 HAG’s immersive multimedia tour generated annual revenue of 6 million RMB. The entrepreneur, however, does not bear the responsibility of heritage safeguarding as a profit-driven third party. As a subordinate unit of the local garden bureau, the HAG Management Office led the project on the ground. The team’s leading position is reflected in their power to certify what is appropriate to be included as part of the heritage interpretation process and how specific experiences should be translated into the immersive multimedia scene. Our interview with the HAG Management Office illustrates the overlapping roles of local government, conservation practitioners, and the HAG visitors in wrestling with the heritage commodification process, with one interviewee noting:

While the design of each scene is operated by our partner entrepreneur, our experience in the HAG every day feeds into the overall development of the tour. To us, the presentation of this tour is personalized. This distinguishes us from other WHS Suzhou gardens and WHSs across the state.

(I 03)

The HAG Management Office addresses its attempted narrative approach as an experimental representation that foregrounds physical and non-physical heritage, in contrast to the common practice among WHS gardens. It is, however, worth noting that both approaches are successful in generating attraction even though the programs are commodity-led initiatives. Whilst feelings of individual agency are embodied through their ongoing interaction with the external world [

6,

51,

52], visitors interpret, consume, and negotiate the concepts and values of the Classic Garden of Suzhou with limited constraints imposed on them from the format of performative tourism. Visitors’ journals of the HAG immersive multimedia tour illustrate vividly how their interpretations of heritage might echo (see VJ 11) or differ from (see VJ 3) the intended communication. This would also involve interpretations that, although as limited as 1 out of 52 reviewed journals, contest the intended outcome (VJ 39). We are particularly mindful of the fact that the representation of the previously overlooked architecture triggers a variety of feelings and understandings, where mundane activities are increasingly part of the narrative. The interpretation of HAG’S authenticity, therefore, is negotiated among these emerging stakeholders:

You can tell the differences between the HAG at night and during the day. I love the rain scene that is (re)created in the building. The rain, the banana trees, and the sound of thunder, together create a feeling of being there.

(VJ 11)

I am particularly intrigued by the architecture. Scenes in the Li Residence have created a peculiar Chinese horror atmosphere. I hope that there will be a live action role-playing game in the Li Residence.

(VJ 3)

To us, the tour is an imagination of the HAG’s heritage. It does not feel authentic.

(VJ 39)

8. Discussion

As China’s heritage commodification remains governed entirely by the local authorities [

53], they, in turn, take administrative triumphs for successful outcomes. It is clear from the HAG case that intervention from heritage agencies in the heritage commodification process remains extremely limited. Rather, programs are entirely operated by the profit-driven private section, of which their participation in actual heritage safeguarding remains unclear. The country’s tourism-led conservation framework has therefore approached WHSs with a clear purpose: to serve the municipality. The primary starting point and purpose of heritage representation, therefore, remains heavily revolved around administrative and financial rewards. Within this context, heritage representation is considered an effective approach to generating tourism attraction and has ongoing effects on not only the HAG alone but a few of China’s WHSs. Instances involve light display in the West Lake Cultural Landscape (Hangzhou), opera performance in the Forbidden City (Beijing), and folklore performance of Mogao Caves (Dunhuang), to name a few. Having achieved wide recognition, these representation attempts are incredibly resource hungry and further portray WHSs as local assets that compete with one other.

Where does this leave the narrators, then, when heritage representation is driven and operated by the municipality? The only way in which human beings can conceptualize self-identity is through narrative [

54]. The complexity of creating ‘narratives’ in a landscape is critical in working towards a definition of heritage as an entanglement of dependencies between feelings and things [

55,

56]. Yet it is precisely because local authorities and the market have long aligned their interests within the heritage management system that limited space is left for credible professional interventions. For the HAG team, the tour as a heritage presentation outcome is set apart from other WHSs as their role extends to the narrator while leading the process. As multimedia scenes in the Li Residence resonate with the team’s understanding of the building fabric and associated daily memories and feelings, one would be walking through not simply the building fabric but also their interpretations of the HAG. This demonstrates a subtle negotiation within the seemingly unbreakable government-market heritage management system. The presence of narrators, regardless of how implicit, is partially accountable for the manifestations of immaterial culture in practice at HAG as part of its shifting conservation practice.

The perception of the HAG’s heritage does not necessarily require a ‘proper’ interpretation from the experts [

13], despite the transitioning interplay between the government, conservation practitioners, and the public at the site. Rather, it is the entangled personal experiences, expressions, and emotions that produce stories that unify the material and immaterial heritage into a more holistic sense of place [

57,

58]. The visitor journals illustrate that the (re)designed HAG story triggers complex personal interpretations that expand the HAG’s curated scenes into diverse narratives, although they seem to have been put in a position of obscurity in the current discourse. The depiction of everyday activities and feelings in the visitor journals reflects the HAG’s shift from a site previously portrayed as transcendent to a site that supports society to reproduce commonplace practices through social performance. This reinforces the notion that conservation is fundamentally a process concerned with preserving and enhancing the qualities of heritage for user experience rather than preventing physical change [

58,

59,

60].

9. Conclusions

The results of the study shed light on the evolving conservation practices at the Humble Administrator’s Garden (HAG), exemplifying the complexities and challenges faced in preserving cultural heritage within the context of China’s tourism-driven approach. Our investigation combined both historical and firsthand data to dissect the HAG’s conservation evolution. We have evidenced how this has led to a somewhat predictable approach toward conservation methods and practices, with an initial focus on the faithful restoration of the spatial form of both architecture and landscape. The Li Residence has been transformed from a garden museum to a residential showcase space as part of the garden’s prioritization as the main tourist resource. Yet this transformation—driven by the need to manage high tourist traffic—raises questions about the balance between architectural preservation and intangible cultural heritage representation within the site.

The growing global interest in more intangible and integrated approaches towards heritage highlights how cultural heritage landscapes are rich in meanings and values, serving as environments of memory and accommodating various contemporary interpretations of ‘place’. From this critical perspective, we have consolidated interviews and visitor journals to show how the HAG’s immersive multimedia tour attempts to revive a fading sense of unity between architecture and landscape with reimagined intangible heritage—such as literati aesthetics, activities, and feelings—being translated into scenes within the Li Residence and garden. Previously silent narratives are actively shaped and foregrounded by encouraging personal experiences and interpretations of the site’s physical and non-physical heritage. This creates opportunities for further reflections on the tacit knowledge, practices, complex feelings, and stories that constitute the HAG heritage landscape in perpetuating its relevance to contemporary society. It also distinguishes it from common practices amongst other WHS gardens. We have indicated how this approach also dilutes the rigid division between architecture and landscape, demonstrating the complex interplay between the two elements. The concept of ‘place’ subsequently becomes more inclusive, considering both natural and built heritage and both tangible and intangible heritage domains.

It is clear from archives and interview results that the involvement of various stakeholders at the HAG, including the HAG Management Office, local government, conservation practitioners, and visitors, emphasizes the contested nature of heritage commodification. The immersive multimedia tour, a commodity-led initiative, has proven successful in generating economic profit whilst also inviting diverse interpretations and emotions that necessitate a constant reappraisal of the conservation strategies employed. The study’s mixed methodological approach highlights the importance of involving previously silent stakeholders in the conservation process, with the HAG Management Office’s multimedia tour facilitating subtle negotiations within the government-market heritage management system.

Ultimately, the conservation of cultural heritage landscapes must strive for a more holistic approach, encompassing tangible and intangible elements and embracing diverse narratives and interpretations. The HAG’s attempted experiment to reuse, reinterpret, and represent its former heritage buildings indicates a changing conservation discourse where intangible heritage is influencing approaches toward physical heritage assets. This is a critical step towards the formation of a holistic narration of place that can more appropriately conserve and evolve WHS gardens and alike for future generations.