Relaxation and Fascination through Outside Views of Mexican Dwellings

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Relaxation, Fascination, and Psychological Restoration in Relation to the Environment

“To experience something like landscape involves a multitude of relations: e.g., that of the changing movement, that of thinking clearly about that experience—or about something else, that of daydreaming or of being specific, of feeling tired or invigorated, or stressed or lost—one after the other, at the same time.”

- Effective functioning: This is the subjective cognitive well-being related to a perception of being effective, e.g., being focused, alert, and positive [18];

- Tranquility (at peace) reflects a calmed state of mind, e.g., being relaxed, comfortable, and patient [18];

- Distraction conveys a set of behavioral manifestations related to a deficit of directed attention, e.g., being disorganized and forgetful [18].

1.2. Environmental Qualities and Elements Related to Restoration and Preference

1.3. Research Questions

- Q1.

- How can outside views be categorized according to their environmental qualities?

- Q2.

- Which environmental dimensions of the views present stronger direct relations with fascination, relaxation, and cognitive well-being?

- Q3.

- What are the implications of this study for the architectural discipline?

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. The Psychological Scales and the Outside View Statements

2.2.2. Photographs and the Evaluation of the Environmental Dimensions of the Views

2.3. Statistical Analyses

2.3.1. Multidimensional Scaling Analysis

2.3.2. Regularized Partial Correlation Network

3. Results

3.1. Categorization of the Views According to Their Environmental Dimensions

- Immersive views of extensive landscapes with vegetation (27 views),

- Non-immersive views of landscapes with vegetation (27 views),

- Views of courtyards with vegetation (8 views),

- Views of commonplace scenes (17 views), and

- Views of mostly built elements (10 views).

3.2. Descriptive Statistics of the Categories of Views

3.2.1. Immersive Views of Extensive Landscapes with Vegetation

3.2.2. Non-Immersive Views of Landscapes with Vegetation

3.2.3. Views of Courtyards with Vegetation

“Enclosure enhances our sensibilities by eliminating other distractions and literally captures the atmosphere. The lack of visual freedom created by boundary walls heightens perception through our other senses, liberating us from overemphasis on sight.”

3.2.4. Views of Commonplace Scenes

3.2.5. Views of Mostly Built Elements

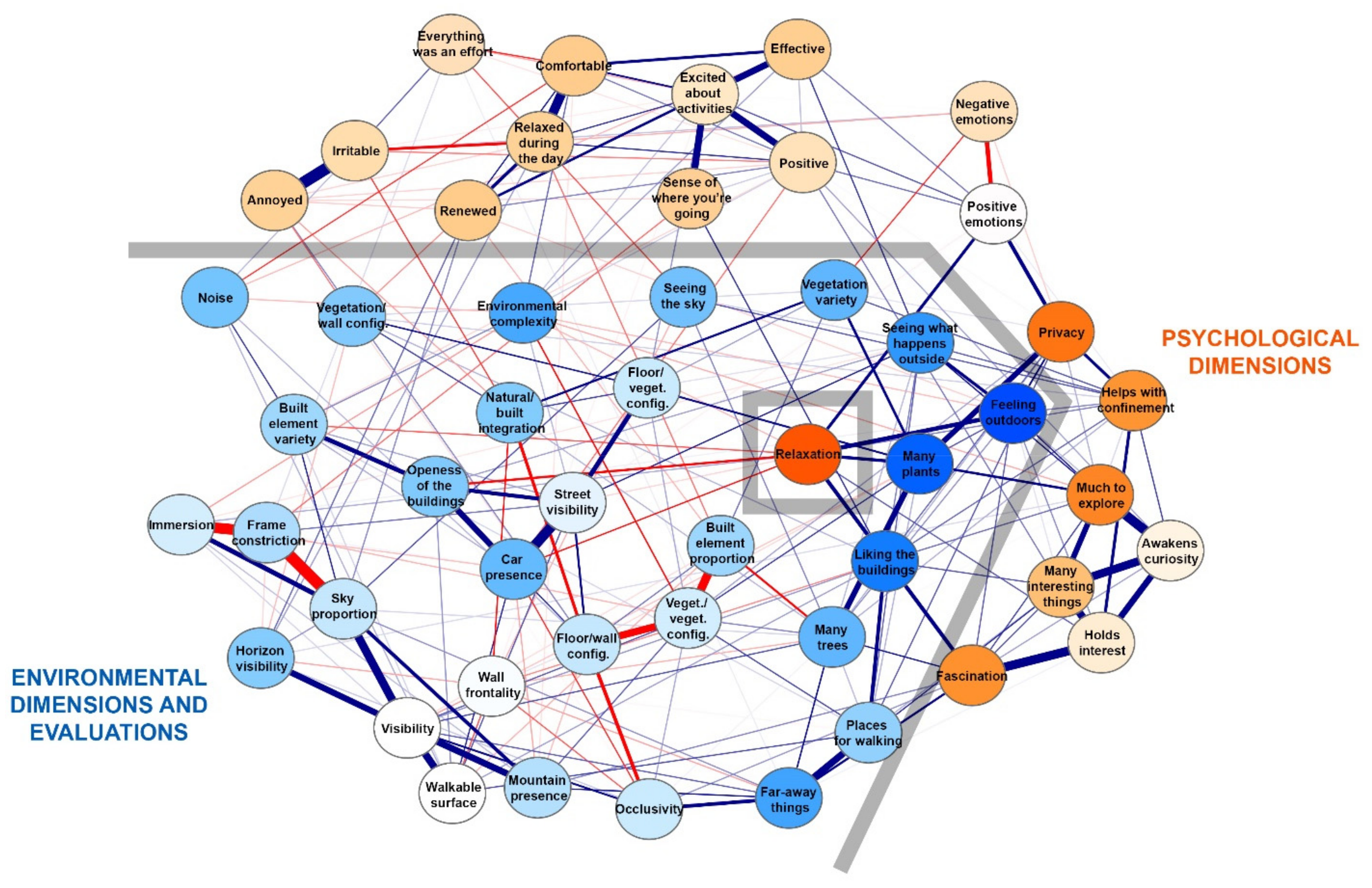

3.3. The Regularized Partial Correlation Network of the Environmental and Psychological Dimensions

3.3.1. Relations with Relaxation and the Other Psychological States

3.3.2. Relations with the Fascination Items

3.3.3. Relations with the Well-Being Items

3.3.4. Relations with the Attractiveness of the Built Elements

3.3.5. General Relations between Environmental and Psychological Dimensions during View Contemplation

- The psychological dimensions that presented stronger direct relations with the environmental aspects of an outside view were (a) relaxation and (b) the privacy felt during contemplation. Therefore, assuming that the environmental dimensions antecede the psychological ones, it may be inferred that changes in the environmental dimensions of an outside view will likely affect relaxation and privacy;

- The environmental dimensions that were most strongly related to the psychological states were (a) the capability of the environment to make people feel as if they were outdoors, (b) the quantity of moderate-size plants as evaluated by the participants, and (c) the attractiveness of the built elements. The latter three environmental aspects may have had the strongest influence on people’s psychological states while contemplating the views. It is interesting to pinpoint that liking the buildings was directly related to five psychological states, as shown in Figure 4; nevertheless, all these relations were of moderate to low weight.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Q1. How Can Outside Views Be Categorized According to Their Environmental Qualities?

4.2. Q2. Which Environmental Dimensions of the Views Present Stronger Direct Relations with Fascination, Relaxation, and Cognitive Well-Being?

4.3. Q3. What Are the Implications of This Study for the Architectural Discipline?

- The integration of the exterior with interior space (making people feel outdoors) is as important as the merging of the natural and the built when pursuing people’s relaxation and cognitive well-being. Considering that the integration of natural and built elements presented negative relations with irritability and annoyance, and that the attractiveness of the built elements may be increased with vegetation/wall configurations in which the walls of buildings are behind vegetation, it is relevant to design places with such qualities. In general, the simultaneous consideration of the natural and the built in designed environments is a relevant theme for future studies;

- Courtyards with vegetation are reduced and secluded spaces that offer opportunities for restoration and relaxation and helped the inhabitants withstand confinement. Therefore, it is not mandatory to have extensive views or high sky visibility to have those benefits. Instead, a more modest space with plants far from the street is sufficient to experience a restorative parenthesis or pause in the middle of an urban world. Courtyards and the views they allow must be included in houses and apartments to generate well-being in their inhabitants;

- People do not evaluate their liking for built elements in an isolated manner, but take into account aspects of the context, such as the pleasant walks that the spaces between buildings afford. Architectural works and the places that they accompany compose an experiential whole. Therefore, architects should consider people’s holistic manner of experiencing during the design process to generate well-being through the built environment;

- Several formal aspects of architecture (variety and proportion of built elements, openness of the buildings, and floor/wall configuration) influence human relaxation and well-being. The formal or aesthetic regarding buildings cannot be considered a secondary aspect in architecture after the functional, since the generation of well-being through aesthetics is also a function that a built environment must possess. Architecture is not only about the creation of functional buildings, but also about the generation of environments that allow users themselves to function effectively;

- People react positively to specific qualities of the environment and know their preferences, but this does not indicate that they know how to generate a pleasant environment as a whole or that they have the resources to do so. The wide variety of materials, colors, and architectural details of the built elements appearing in the views was related to a lower relaxation and was produced mainly by self-built dwellings. While choosing the dwelling style may satisfy the owners, the landscape composed of many such dwellings may be disharmonious.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Type | Item/Dimension | Scale | Categories of Views | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immersive Views of Extensive Landscapes with Vegetation (27) | Non-Immersive Views of Landscapes with Vegetation (27) | Views of Courtyards with Vegetation (8) | Views of Commonplace Scenes (17) | Views of Mostly Built Elements (10) | Total (89) | |||||||||

| Fascination (quantitative items) | This view is fascinating. | 0–10 | 7.78 | 1.97 | 6.48 | 2.86 | 8.25 | 2.05 | 3.71 | 2.44 | 4.50 | 1.43 | 6.28 | 2.81 |

| Following what is going on in this view really holds my interest. | 7.85 | 2.09 | 6.30 | 2.87 | 8.00 | 2.14 | 5.12 | 1.93 | 4.70 | 2.31 | 6.52 | 2.61 | ||

| This view awakens my curiosity. | 7.37 | 2.15 | 5.63 | 3.51 | 7.38 | 2.77 | 4.88 | 2.20 | 4.80 | 3.19 | 6.08 | 2.96 | ||

| There is much to explore and discover in this view. | 7.30 | 2.41 | 5.74 | 3.41 | 6.75 | 3.01 | 4.18 | 2.38 | 3.60 | 2.07 | 5.76 | 3.03 | ||

| My attention is drawn to many interesting things in this view. | 7.52 | 2.24 | 5.59 | 2.80 | 6.88 | 2.95 | 4.24 | 2.46 | 4.20 | 2.10 | 5.88 | 2.80 | ||

| Effective functioning (quantitative items) | Energetic and excited about what you are doing. | 0–4 | 2.78 | 1.15 | 2.30 | 1.23 | 2.25 | 1.16 | 1.88 | 1.05 | 2.40 | 1.35 | 2.37 | 1.20 |

| Life is interesting and challenging. | 2.74 | 1.06 | 2.85 | 1.10 | 3.00 | 0.93 | 2.29 | 1.05 | 2.90 | 1.10 | 2.73 | 1.06 | ||

| Focused. | 2.63 | 1.08 | 2.30 | 1.20 | 2.50 | 1.41 | 1.88 | 1.05 | 3.00 | 1.05 | 2.42 | 1.17 | ||

| Effective. | 2.59 | 0.84 | 2.41 | 1.05 | 2.13 | 0.83 | 1.94 | 0.66 | 2.80 | 0.92 | 2.39 | 0.91 | ||

| Positive. | 2.93 | 0.87 | 2.41 | 0.97 | 2.63 | 1.30 | 1.71 | 1.21 | 2.50 | 0.97 | 2.46 | 1.09 | ||

| Able to get really absorbed in a task. | 2.33 | 1.21 | 2.30 | 1.07 | 2.38 | 1.19 | 2.12 | 1.27 | 2.40 | 1.35 | 2.29 | 1.17 | ||

| Alert. | 2.52 | 1.05 | 2.30 | 1.23 | 2.63 | 1.30 | 1.88 | 0.99 | 2.00 | 1.33 | 2.28 | 1.16 | ||

| Satisfied with how things have been going lately. | 1.85 | 1.03 | 1.85 | 0.99 | 1.63 | 1.41 | 1.29 | 1.16 | 1.40 | 1.26 | 1.67 | 1.11 | ||

| You have a good sense of where you’re going. | 2.89 | 0.97 | 2.11 | 1.12 | 2.63 | 1.30 | 2.18 | 1.13 | 2.80 | 1.14 | 2.48 | 1.13 | ||

| Attentive. | 2.63 | 0.97 | 2.26 | 0.76 | 2.63 | 1.19 | 2.06 | 1.20 | 2.60 | 1.17 | 2.40 | 1.01 | ||

| Renewed. | 2.11 | 1.01 | 1.85 | 1.03 | 2.00 | 1.60 | 1.41 | 1.06 | 1.50 | 1.08 | 1.82 | 1.10 | ||

| Tranquility (quantitative items) | Relaxed. | 0–4 | 2.22 | 1.01 | 2.00 | 1.14 | 1.50 | 1.20 | 1.24 | 1.20 | 1.80 | 1.03 | 1.85 | 1.14 |

| Comfortable. | 2.59 | 1.15 | 2.44 | 0.89 | 2.00 | 1.41 | 2.29 | 1.31 | 2.90 | 1.20 | 2.47 | 1.14 | ||

| Irritable. | 1.56 | 0.97 | 1.70 | 1.30 | 1.50 | 1.07 | 2.00 | 1.32 | 1.90 | 1.29 | 1.72 | 1.18 | ||

| Everything was an effort. | 1.93 | 0.83 | 2.19 | 1.00 | 2.13 | 1.46 | 1.94 | 1.25 | 2.10 | 0.74 | 2.04 | 1.01 | ||

| Patient. | 2.11 | 0.97 | 2.11 | 0.85 | 2.88 | 1.13 | 1.76 | 1.09 | 2.40 | 1.17 | 2.15 | 1.02 | ||

| Annoyed. | 1.52 | 1.01 | 1.67 | 1.00 | 1.38 | 1.51 | 2.06 | 0.97 | 2.20 | 1.14 | 1.73 | 1.07 | ||

| Pressured and overloaded. | 2.15 | 1.23 | 2.67 | 1.27 | 2.88 | 0.83 | 2.18 | 1.19 | 2.40 | 1.43 | 2.40 | 1.23 | ||

| Distraction (quantitative items) | Forgetful. | 0–4 | 1.52 | 0.94 | 1.59 | 1.05 | 1.75 | 0.46 | 2.06 | 0.97 | 1.80 | 1.23 | 1.70 | 0.98 |

| Disorganized. | 1.52 | 0.98 | 1.63 | 1.24 | 1.00 | 1.20 | 1.76 | 1.20 | 1.80 | 1.55 | 1.58 | 1.19 | ||

| You were losing or misplacing things. | 1.15 | 0.82 | 1.37 | 1.28 | 1.13 | 1.46 | 1.29 | 0.99 | 1.70 | 1.16 | 1.30 | 1.09 | ||

| It is difficult to finish things you have started. | 1.30 | 1.10 | 1.48 | 0.98 | 1.88 | 1.25 | 1.65 | 1.06 | 1.70 | 1.64 | 1.52 | 1.13 | ||

| Making decisions is difficult. | 1.74 | 1.06 | 1.78 | 1.19 | 1.75 | 1.16 | 2.00 | 0.94 | 1.60 | 1.58 | 1.79 | 1.13 | ||

| Other psychological states and emotions had while observing the view (quantitative and open-ended items) | I feel relaxed while looking at this view. | 0–10 | 8.78 | 1.63 | 7.07 | 2.80 | 9.88 | 0.35 | 5.94 | 2.88 | 7.20 | 2.39 | 7.64 | 2.59 |

| Having this view helps me to withstand the confinement. | 8.04 | 2.47 | 7.67 | 3.04 | 8.75 | 1.83 | 6.65 | 2.83 | 4.80 | 2.86 | 7.36 | 2.88 | ||

| Looking at this view gives me a moment of privacy. | 7.52 | 2.69 | 6.44 | 3.12 | 7.13 | 2.90 | 3.76 | 2.51 | 4.30 | 2.41 | 6.08 | 3.10 | ||

| Positive emotions. | Count | 1.74 | 0.81 | 1.15 | 0.77 | 2.13 | 1.25 | 1.06 | 0.97 | 1.30 | 0.67 | 1.42 | 0.91 | |

| Negative emotions. | 0.33 | 0.55 | 0.48 | 0.75 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.41 | 0.62 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.43 | 0.66 | ||

| Low-arousal positive emotions. | 0/1 | 0.93 | 0.27 | 0.74 | 0.45 | 0.88 | 0.35 | 0.65 | 0.49 | 0.90 | 0.32 | 0.81 | 0.40 | |

| High-arousal positive emotions. | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.10 | 0.32 | 0.12 | 0.33 | ||

| Low-arousal negative emotions. | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.30 | 0.48 | 0.11 | 0.32 | ||

| High-arousal negative emotions. | 0.07 | 0.27 | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.42 | 0.10 | 0.30 | ||

| Thoughts had while observing the view (open-ended item) | Going out/outdoor activities. | 0/1 | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.25 | 0.46 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.40 | 0.52 | 0.18 | 0.39 |

| Mind in blank/tries not to think/just enjoys. | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.42 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.20 | 0.42 | 0.13 | 0.34 | ||

| Thinks about relaxation/intends to relax. | 0.07 | 0.27 | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.42 | 0.09 | 0.29 | ||

| Personal thoughts. | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.42 | 0.10 | 0.30 | ||

| Thoughts transcending the present moment and place. | 0.37 | 0.49 | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.25 | 0.46 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.40 | 0.52 | 0.24 | 0.43 | ||

| The future in general. | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.10 | 0.32 | 0.09 | 0.29 | ||

| Confinement/pandemic. | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.37 | 0.49 | 0.38 | 0.52 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.10 | 0.32 | 0.24 | 0.43 | ||

| Type | Item/Dimension | Scale | Categories of Views | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immersive Views of Extensive Landscapes with Vegetation (27) | Non-Immersive Views of Landscapes with Vegetation (27) | Views of Courtyards with Vegetation (8) | Views of Commonplace Scenes (17) | Views of Mostly Built Elements (10) | Total (89) | |||||||||

| Environmental evaluations (quantitative items) | When I look at this view, I feel like being outdoors. | 0–10 | 8.70 | 1.59 | 6.67 | 3.42 | 9.13 | 1.36 | 5.59 | 3.20 | 6.50 | 2.84 | 7.28 | 2.95 |

| I really like the built elements visible from here. | 7.04 | 3.48 | 6.11 | 3.08 | 5.00 | 4.57 | 3.88 | 2.96 | 3.10 | 3.03 | 5.53 | 3.55 | ||

| I can see in this view places where I like to walk. | 7.04 | 3.30 | 5.78 | 3.91 | 2.63 | 2.83 | 1.88 | 2.34 | 4.30 | 3.56 | 4.97 | 3.82 | ||

| I see things that are far away from here in this view. | 7.74 | 2.86 | 6.81 | 3.04 | 3.38 | 3.34 | 2.24 | 3.15 | 2.30 | 2.21 | 5.40 | 3.75 | ||

| This view allows me to see what is happening outside. | 8.26 | 2.26 | 7.44 | 2.97 | 6.00 | 3.38 | 6.59 | 3.10 | 7.00 | 3.53 | 7.35 | 2.93 | ||

| I can see the sky very well in this view. | 9.37 | 1.01 | 8.74 | 2.19 | 8.25 | 2.43 | 8.12 | 2.45 | 9.30 | 1.57 | 8.83 | 1.94 | ||

| Many plants can be seen from this location. | 8.00 | 2.34 | 6.67 | 3.01 | 7.88 | 3.44 | 4.47 | 3.00 | 3.40 | 2.72 | 6.39 | 3.22 | ||

| I can see many trees from here. | 8.48 | 1.72 | 7.11 | 2.62 | 5.00 | 4.38 | 5.24 | 2.75 | 2.20 | 2.66 | 6.43 | 3.23 | ||

| Noise. | 0–2 | 1.00 | 0.62 | 1.00 | 0.55 | 1.13 | 0.35 | 1.18 | 0.53 | 1.10 | 0.57 | 1.06 | 0.55 | |

| Liked elements of the view (open-ended item) | Trees. | 0/1 | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.30 | 0.47 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.38 |

| Vegetation in general (includes trees). | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.44 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.30 | 0.48 | 0.37 | 0.49 | ||

| Sky/clouds. | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.22 | 0.42 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.24 | 0.44 | 0.20 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 0.43 | ||

| The view as a whole. | 0.22 | 0.42 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.46 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.32 | ||

| Reported Elements of the view (open-ended item) | Environmental complexity. | Count | 4.00 | 1.78 | 4.70 | 1.38 | 3.00 | 0.76 | 4.12 | 1.45 | 4.70 | 2.16 | 4.22 | 1.63 |

| A tranquil/quiet place. | 0/1 | 0.22 | 0.42 | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.34 | |

| A park, a natural environment. | 0.44 | 0.51 | 0.30 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.42 | ||

| Plants. | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.20 | 0.40 | ||

| Vegetation in general. | 0.78 | 0.42 | 0.89 | 0.32 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.76 | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.80 | 0.40 | ||

| An extensive view. | 0.33 | 0.48 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.32 | 0.12 | 0.33 | ||

| Mountains/hills. | 0.52 | 0.51 | 0.37 | 0.49 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 0.46 | ||

| Sky/clouds. | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.48 | 0.51 | 0.75 | 0.46 | 0.41 | 0.51 | 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.50 | ||

| Natural lighting phenomena. | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.07 | 0.27 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.70 | 0.48 | 0.19 | 0.40 | ||

| Houses/apartments. | 0.48 | 0.51 | 0.67 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.59 | 0.51 | 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.50 | ||

| Non-residential buildings. | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.32 | ||

| Electrical installations, dwelling fixtures and fittings. | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.10 | 0.32 | 0.11 | 0.32 | ||

| Elements dividing space or blocking movement (walls, fences). | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 0.47 | 0.40 | 0.52 | 0.11 | 0.32 | ||

| Street/sidewalk. | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.44 | 0.51 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.31 | 0.47 | ||

| Cars in general. | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.44 | 0.51 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0.30 | 0.48 | 0.31 | 0.47 | ||

| Moving cars. | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 0.47 | 0.10 | 0.32 | 0.16 | 0.37 | ||

| People in general. | 0.30 | 0.47 | 0.33 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.41 | 0.51 | 0.20 | 0.42 | 0.29 | 0.46 | ||

| People walking/doing activities. | 0.22 | 0.42 | 0.30 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 0.49 | 0.10 | 0.32 | 0.24 | 0.43 | ||

| Birds/birdsong. | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.20 | 0.42 | 0.19 | 0.40 | ||

| Visibility/immersion (photograph evaluation) | Visibility. | 1–3 | 2.89 | 0.32 | 2.04 | 0.71 | 1.13 | 0.35 | 1.41 | 0.51 | 1.10 | 0.32 | 1.99 | 0.85 |

| Maximum depth. | 2.96 | 0.19 | 2.26 | 0.71 | 1.50 | 0.93 | 1.41 | 0.62 | 1.10 | 0.32 | 2.11 | 0.88 | ||

| Depth variety. | 2.96 | 0.19 | 2.81 | 0.40 | 1.75 | 0.89 | 2.00 | 0.79 | 1.50 | 0.53 | 2.46 | 0.75 | ||

| Walkable surface. | 2.07 | 0.83 | 1.85 | 0.72 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.35 | 0.49 | 1.30 | 0.48 | 1.69 | 0.75 | ||

| Occlusivity. | 2.59 | 0.57 | 2.11 | 0.85 | 1.75 | 0.71 | 1.47 | 0.72 | 1.30 | 0.48 | 2.01 | 0.83 | ||

| Non-intervisibility of the visible spaces. | 0–2 | 1.48 | 0.80 | 1.15 | 0.60 | 0.38 | 0.52 | 0.76 | 0.83 | 0.50 | 0.71 | 1.03 | 0.80 | |

| Horizon visibility. | 0.70 | 0.82 | 0.19 | 0.56 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 0.62 | ||

| Sky proportion. | 1.78 | 0.42 | 1.22 | 0.51 | 0.75 | 0.46 | 0.94 | 0.24 | 0.70 | 0.48 | 1.24 | 0.58 | ||

| Height level of the observer. | 0–3 | 2.19 | 0.68 | 1.81 | 0.68 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 1.18 | 0.39 | 1.10 | 0.57 | 1.61 | 0.81 | |

| Observation distance to the outside environment. | 0.63 | 0.69 | 1.15 | 0.53 | 1.63 | 0.52 | 1.35 | 0.61 | 1.50 | 0.71 | 1.11 | 0.70 | ||

| Roof enclosure. | 0.44 | 0.64 | 1.15 | 0.53 | 0.75 | 0.89 | 0.94 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.84 | 0.71 | ||

| Lateral wall enclosure. | 0.37 | 0.56 | 0.96 | 0.59 | 1.63 | 0.74 | 1.35 | 0.61 | 1.60 | 0.84 | 0.99 | 0.78 | ||

| Frame constriction. | 0–2 | 0.44 | 0.70 | 1.74 | 0.59 | 1.13 | 0.35 | 1.53 | 0.62 | 1.80 | 0.42 | 1.26 | 0.82 | |

| Observation through a transparent surface. | 0/1 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.56 | 0.51 | 0.25 | 0.46 | 0.41 | 0.51 | 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.35 | 0.48 | |

| Curtain presence. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.70 | 0.47 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.33 | 0.47 | ||

| Observation through a grid. | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.56 | 0.51 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.71 | 0.47 | 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.42 | 0.50 | ||

| Immersion. | 0–3 | 2.85 | 0.36 | 1.19 | 0.92 | 2.50 | 0.76 | 1.71 | 0.85 | 1.20 | 1.40 | 1.91 | 1.09 | |

| Extralimitary property observation. | 0–2 | 1.81 | 0.40 | 1.67 | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 1.53 | 0.51 | 1.20 | 0.92 | 1.53 | 0.64 | |

| Vegetation/nature (photograph evaluation) | Vegetation proportion. | 0–3 | 2.15 | 0.66 | 1.96 | 0.65 | 2.00 | 0.76 | 1.41 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 1.75 | 0.80 |

| Living vegetation proportion. | 1.89 | 0.75 | 1.93 | 0.62 | 2.00 | 0.76 | 1.41 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 1.66 | 0.78 | ||

| Tree proportion. | 1.89 | 0.70 | 1.85 | 0.66 | 1.38 | 1.06 | 1.35 | 0.49 | 0.30 | 0.48 | 1.55 | 0.83 | ||

| Green area presence. | 0–2 | 1.15 | 0.82 | 0.52 | 0.64 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.74 | |

| Maximum vegetation height. | 0–4 | 3.30 | 0.72 | 3.44 | 0.58 | 2.25 | 0.89 | 3.18 | 0.64 | 1.00 | 1.05 | 2.97 | 1.05 | |

| Vegetation variety. | 0–3 | 1.63 | 0.56 | 1.63 | 0.56 | 1.75 | 0.46 | 1.35 | 0.49 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 1.47 | 0.64 | |

| Vegetation/soil contact. | 2.07 | 1.00 | 1.63 | 0.97 | 1.38 | 1.06 | 0.94 | 0.75 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 1.48 | 1.03 | ||

| Vegetation/wall configuration. | 0–2 | 0.93 | 0.68 | 0.89 | 0.42 | 1.13 | 0.83 | 0.94 | 0.24 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.89 | 0.55 | |

| Wall/vegetation configuration. | 1.26 | 0.59 | 1.00 | 0.55 | 0.63 | 0.92 | 0.88 | 0.49 | 0.30 | 0.48 | 0.94 | 0.65 | ||

| Vegetation/vegetation configuration. | 1.22 | 0.75 | 0.59 | 0.69 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.62 | 0.75 | ||

| Floor/vegetation configuration. | 0.89 | 0.75 | 1.04 | 0.44 | 0.75 | 0.89 | 0.76 | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.85 | 0.61 | ||

| Natural and built integration. | 0.70 | 0.54 | 0.89 | 0.64 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.59 | ||

| Vegetation unity. | 1.52 | 0.64 | 1.19 | 0.88 | 1.50 | 0.76 | 0.88 | 0.70 | 0.10 | 0.32 | 1.13 | 0.83 | ||

| Mountain presence. | 0.85 | 0.36 | 0.37 | 0.49 | 0.25 | 0.46 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.39 | 0.49 | ||

| Built/human-made elements (photograph evaluation) | Built element proportion. | 1–3 | 1.56 | 0.51 | 1.89 | 0.42 | 2.00 | 0.53 | 2.18 | 0.39 | 2.50 | 0.53 | 1.92 | 0.55 |

| Built element variety. | 0–2 | 1.30 | 0.72 | 1.33 | 0.62 | 0.25 | 0.46 | 1.24 | 0.44 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 1.17 | 0.71 | |

| Architectural detail. | 0.56 | 0.51 | 0.85 | 0.60 | 0.25 | 0.46 | 0.94 | 0.56 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.72 | 0.60 | ||

| Floor/wall configuration. | 0.85 | 0.72 | 1.33 | 0.62 | 1.00 | 0.76 | 1.71 | 0.47 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 1.30 | 0.71 | ||

| Wall frontality. | 1.04 | 0.65 | 1.26 | 0.76 | 1.88 | 0.35 | 1.71 | 0.59 | 1.50 | 0.71 | 1.36 | 0.71 | ||

| Openness of the buildings. | 0–4 | 0.64 | 0.56 | 0.81 | 0.52 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.85 | 0.42 | 0.77 | 0.92 | 0.69 | 0.59 | |

| Dwelling presence. | 0–3 | 1.93 | 1.07 | 1.67 | 0.96 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 1.29 | 0.69 | 1.00 | 0.82 | 1.49 | 0.99 | |

| Street visibility. | 0–2 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 1.67 | 0.55 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.47 | 0.80 | 1.30 | 0.95 | 1.21 | 0.89 | |

| Car presence. | 0.37 | 0.69 | 1.37 | 0.69 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.35 | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.88 | 0.86 | ||

References

- De la Fuente Suárez, L.A. An enabling technique for describing experiences in architectural environments. A/Z ITU J. Fac. Archit. 2022, 19, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åsdam, K. Space, place and the gaze: Landscape architecture and contemporary visual art. In Exploring the Boundaries of Landscape Architecture; Bell, S., Herlin, I.S., Stiles, R., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012; pp. 117–130. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, T. Restorative Environments. In Encyclopedia of Applied Psychology; Spielberger, C.D., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 3, pp. 273–279. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, T.; Korpela, K.; Evans, G.W.; Gärling, T. A Measure of Restorative Quality in Environments. Scand. Hous. Plan. Res. 1997, 14, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, A.E.; Koole, S.L.; van der Wulp, N.Y. Environmental Preference and Restoration: (How) Are They Related? J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielinis, E.; Bielinis, L.; Krupińska-Szeluga, S.; Łukowski, A.; Takayama, N. The Effects of a Short Forest Recreation Program on Physiological and Psychological Relaxation in Young Polish Adults. Forests 2019, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herman, J.A. The Concept of Relaxation. J. Holist. Nurs. 1985, 3, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielinis, E.; Takayama, N.; Boiko, S.; Omelan, A.; Bielinis, L. The Effect of Winter Forest Bathing on Psychological Relaxation of Young Polish Adults. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Soto, J.; Montero-López Lena, M.; Cordova y Vázquez, A. Restauración Psicológica y Naturaleza Urbana: Algunas Implicaciones Para La Salud Mental. Salud Ment. 2014, 37, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Subiza-Pérez, M.; Korpela, K.; Pasanen, T. Still Not That Bad for the Grey City: A Field Study on the Restorative Effects of Built Open Urban Places. Cities 2021, 111, 103081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidlow, C.J.; Jones, M.V.; Hurst, G.; Masterson, D.; Clark-Carter, D.; Tarvainen, M.P.; Smith, G.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M. Where to Put Your Best Foot Forward: Psycho-Physiological Responses to Walking in Natural and Urban Environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joye, Y.; Pals, R.; Steg, L.; Evans, B.L. New Methods for Assessing the Fascinating Nature of Nature Experiences. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herzog, T.R.; Black, A.M.; Fountaine, K.A.; Knotts, D.J. Reflection and attentional recovery as distinctive benefits of restorative environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1997, 17, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Duvall, J.; Kaplan, R. Attention Restoration Theory: Exploring the Role of Soft Fascination and Mental Bandwidth. Environ. Behav. 2019, 51, 1055–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splan, K. The Effects of Fascination and Extent on Judgements of Tranquility. Master’s Thesis, University of Utah, Salk Lake City, UT, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, E. A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful; Printed for, R. and J. Dodsley: London, UK, 1757. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R. The Nature of the View from Home: Psychological Benefits. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 507–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Soto, J. Impacto de la Naturaleza Urbana Próxima: Un Modelo Ecológico Social. Ph.D. Thesis, UNAM, Mexico City, Mexico, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S. Human Responses to Vegetation and Landscapes. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 1986, 13, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, E.; Corraliza, J.A.; Collado, S.; Sevillano, V. Preference, restorativeness and perceived environmental quality of small urban spaces/Preferencia, restauración y calidad ambiental percibida en plazas urbanas. Psyecology 2016, 7, 152–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Kim, E.J. Differences of Restorative Effects While Viewing Urban Landscapes and Green Landscapes. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van den Berg, A.E.; Jorgensen, A.; Wilson, E.R. Evaluating restoration in urban green spaces: Does setting type make a difference? Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2014, 127, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Mavoa, S.; Zhao, J.; Raphael, D.; Smith, M. The Association between Green Space and Adolescents’ Mental Well-Being: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Li, D.; Larsen, L.; Sullivan, W.C. A Dose-Response Curve Describing the Relationship Between Urban Tree Cover Density and Self-Reported Stress Recovery. Environ. Behav. 2016, 48, 607–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, P.Y.; Dillon, D.; Chew, P.K.H. A Guide to Nature Immersion: Psychological and Physiological Benefits. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R. The Psychological Benefits of Nearby Nature. In The Role of Horticulture in Human Well-Being and Social Development: A National Symposium; Relf, D., Ed.; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 1992; pp. 125–133. [Google Scholar]

- Honold, J.; Lakes, T.; Beyer, R.; van der Meer, E. Restoration in Urban Spaces: Nature Views From Home, Greenways, and Public Parks. Environ. Behav. 2016, 48, 796–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peron, E.; Berto, R.; Purcell, T. Restorativeness, Preference and the Perceived Naturalness of Places. Medio Ambient. Comport. Hum. 2002, 3, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- White, E.V.; Gatersleben, B. Greenery on Residential Buildings: Does It Affect Preferences and Perceptions of Beauty? J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Booth, N.K. Foundations of Landscape Architecture: Integrating Form and Space Using the Language of Site Design; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nordh, H.; Østby, K. Pocket Parks for People—A Study of Park Design and Use. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlwill, J.F.; Harris, G. Response to Congruity or Contrast for Man-Made Features in Natural-Recreation Settings. Leis. Sci. 1980, 3, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornioli, A.; Parkhurst, G.; Morgan, P.L. Psychological Wellbeing Benefits of Simulated Exposure to Five Urban Settings: An Experimental Study From the Pedestrian’s Perspective. J. Transp. Health 2018, 9, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopelliti, M.; Carrus, G.; Bonaiuto, M. Is It Really Nature That Restores People? A Comparison with Historical Sites with High Restorative Potential. Front. Psychol. 2019, 9, 2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez-Soto, J.; de la Fuente Suárez, L.A.; Ruiz-Correa, S. Exploring the Links Between Biophilic and Restorative Qualities of Exterior and Interior Spaces in Leon, Guanajuato, Mexico. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 717116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindal, P.J.; Hartig, T. Architectural Variation, Building Height, and the Restorative Quality of Urban Residential Streetscapes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 33, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coburn, A.; Kardan, O.; Kotabe, H.; Steinberg, J.; Hout, M.C.; Robbins, A.; MacDonald, J.; Hayn-Leichsenring, G.; Berman, M.G. Psychological Responses to Natural Patterns in Architecture. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 62, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joye, Y. Architectural Lessons from Environmental Psychology: The Case of Biophilic Architecture. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2007, 11, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herzog, T.R.; Kaplan, S.; Kaplan, R. The Prediction of Preference for Unfamiliar Urban Places. Popul. Environ. 1982, 5, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryan, C.; Browning, W.; Clancy, J.; Andrews, S.; Kallianpurkar, N. Biophilic Design Patterns: Emerging Nature-Based Parameters for Health and Well-Being in the Built Environment. ArchNet IJAR 2014, 8, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostwald, M.J.; Dawes, M.J. The Mathematics of the Modernist Villa: Architectural Analysis Using Space Syntax and Isovists; Birkhäuser: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Gu, N.; Ostwald, M. The mathematics of spatial transparency and mystery: Using syntactical data to visualise and analyse the properties of the Yuyuan Garden. Vis. Eng. 2016, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dawes, M.J.; Ostwald, M.J. Spatio-visual patterns in architecture: An analysis of living rooms in Frank Lloyd Wright’s houses. In Across: Architectural Research through to Practice: 48th International Conference of the Architectural Science Association; Madeo, F., Schnabel, M.A., Eds.; The Architectural Science Association, Genova University Press: Genova, Italy, 2014; pp. 151–162. [Google Scholar]

- Masoudinejad, S.; Hartig, T. Window View to the Sky as a Restorative Resource for Residents in Densely Populated Cities. Environ. Behav. 2020, 52, 401–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, A. The Effect of Window Views Openness and Naturalness on the Perception of Rooms Spaciousness and Brightness: A Visual Preference Study. Sci. Res. Essays 2010, 5, 2275–2287. [Google Scholar]

- Winkel, G.; Saegert, S.; Evans, G.W. An Ecological Perspective on Theory, Methods, and Analysis in Environmental Psychology: Advances and Challenges. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Soto, J.; Montero-López Lena, M. Percepción de Cualidades Restauradoras y Preferencia Ambiental. Rev. Mex. Psicol. 2010, 27, 183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Beil, K.; Hanes, D. The Influence of Urban Natural and Built Environments on Physiological and Psychological Measures of Stress—A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 1250–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tennessen, C.M.; Cimprich, B. Views to Nature: Effects on Attention. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, R.H. Student performance and high school landscapes: Examining the links. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2010, 97, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Fried, E.I. A Tutorial on Regularized Partial Correlation Networks. Psychol. Methods 2018, 23, 617–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; (R 4.1.1) Windows; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: http://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 16 September 2021).

- Epskamp, S.; Cramer, A.O.J.; Waldorp, L.J.; Schmittmann, V.D.; Borsboom, D. Qgraph: Network Visualizations of Relationships in Psychometric Data. J. Stat. Soft. 2012, 48, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pelowski, M.; Leder, H.; Mitschke, V.; Specker, E.; Gerger, G.; Tinio, P.P.L.; Vaporova, E.; Bieg, T.; Husslein-Arco, A. Capturing Aesthetic Experiences with Installation Art: An Empirical Assessment of Emotion, Evaluations, and Mobile Eye Tracking in Olafur Eliasson’s “Baroque, Baroque”! Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pelowski, M.; Hur, Y.-J.; Cotter, K.N.; Ishizu, T.; Christensen, A.P.; Leder, H.; McManus, I.C. Quantifying the If, the When, and the What of the Sublime: A Survey and Latent Class Analysis of Incidence, Emotions, and Distinct Varieties of Personal Sublime Experiences. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2021, 15, 216–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Sparse Inverse Covariance Estimation with the Graphical Lasso. Biostatistics 2008, 9, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christensen, A.J. Dictionary of Landscape Architecture and Construction; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ipsen, D. Space, place and perception: The sociology of landscape. In Exploring the Boundaries of Landscape Architecture; Bell, S., Herlin, I.S., Stiles, R., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012; pp. 60–82. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, K. Captured Landscape: Architecture and the Enclosed Garden, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bringslimark, T.; Hartig, T.; Patil, G.G. The psychological benefits of indoor plants: A critical review of the experimental literature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P. Package ‘networktools’: Tools for Identifying Important Nodes in Networks. 6 October 2021. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/networktools/networktools.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2022).

- Blanco, I.; Contreras, A.; Valiente, C.; Espinosa, R.; Nieto, I.; Vázquez, C. El análisis de redes en psicopatología: Conceptos y metodología. Behav. Psychol. Psicol. Conduct. 2019, 27, 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, I.-C.; Tsai, Y.-P.; Lin, Y.-J.; Chen, J.-H.; Hsieh, C.-H.; Hung, S.-H.; Sullivan, W.C.; Tang, H.-F.; Chang, C.-Y. Using functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (FMRI) to analyze brain region activity when viewing landscapes. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2017, 162, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikei, H.; Song, C.; Igarashi, M.; Namekawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological and psychological relaxing effects of visual stimulation with foliage plants in high school students. Adv. Hortic. Sci. 2014, 28, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Factor | Items | Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived restoration | Fascination |

| 0–10 |

| Cognitive well-being | Effective functioning |

| 0–4 |

| Tranquility |

| 0–4 | |

| Distraction |

| 0–4 |

| Type | Items | Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Other psychological states |

| 0–10 |

| Environmental evaluations |

| 0–10 |

| Type | Items |

|---|---|

| Other psychological states |

|

| Environmental descriptions |

|

| Visibility/Immersion | Levels | |

|---|---|---|

| Visibility. | The horizontal extension of the view: This dimension indicates the openness or the quantity of space visible from a view. | 1–3 |

| Maximum depth. | Distance of the furthest elements found in the view in relation to the observer. | 1–3 |

| Depth variety. | Degree to which the elements present in the view are located at different distances to the observer. | 1–3 |

| Walkable surface. | Quantification of the horizontal plane capable of affording people’s displacement. | 1–3 |

| Occlusivity. | Degree to which some elements of the view are hiding other elements or spaces from the observer’s point of view. | 1–3 |

| Non-intervisibility of the visible spaces. | Level to which the scene presents spaces that are not visible from the other spaces in the view. A high level corresponds to views in which several streets appear, and people on one street cannot see the people on the others. A low level corresponds to views in which the visible space is a single unit, and all the people occupying that space can see each other. | 0–2 |

| Horizon visibility. | Quantity of the line of the horizon that may be appreciated in the view. | 0–2 |

| Sky proportion. | Extension of the sky that is visible in the scene. | 0–2 |

| Height level of the observer. | Quantification of the observer’s height in relation to the landscape or space observed. The zero level corresponds to environments surrounded by walls in which the observers must look upwards to see beyond. Level 1 is ground floor observation, in which the observer looks frontally. Meanwhile, in levels 2 and 3, the observers look down from the first floor, or the second floor or higher, respectively. | 0–3 |

| Observation distance to the outside environment. | Degree of spatial separation between the observer and the outside space. When a participant sees through a window while far away from it, the observation distance is at the highest level. | 0–3 |

| Roof enclosure. | How enclosed the view is regarding the built elements above the observer. | 0–3 |

| Lateral wall enclosure. | Enclosure level of the view caused by the vertical built elements on the observer’s sides. | 0–3 |

| Frame constriction. | Degree to which the built elements restrict the possibilities of having an open view, e.g., a view through a little window. | 0–2 |

| Observation through a transparent surface. | The view is observed through a pane of glass or a mosquito net. | 0/1 |

| Curtain presence. | A fabric curtain frames the view, or the observer sees outside through a blind curtain. | 0/1 |

| Observation through a grid. | The scene is observed through the strips of a grid window or a window grill that fragment the view. | 0/1 |

| Immersion. | Level in which the observer is in direct contact with the outside environment during the observation of the view. Immersion conveys a high multisensory involvement with the wind, the sun, or the exterior weather. In the highest level of immersion, there is no element interfering between the observer and the outside environment, such as glass, a curtain, or window grills. | 0–3 |

| Extralimitary property observation. | Degree to which what is seen in the view is outside of the property boundaries of the dwelling. In the lowest level of this dimension, what is seen in a view is part of the property, e.g., an enclosed courtyard. | 0–2 |

| Vegetation/Nature | Levels | |

|---|---|---|

| Vegetation proportion. | Level of presence of greenery in the scene. | 0–3 |

| Living vegetation proportion. | Quantification of living plants and trees (dead vegetation is not considered). | 0–3 |

| Tree proportion. | Quantity of trees, shrubs, and palm trees in the view. | 0–3 |

| Green area presence. | Quantification of the vegetated spaces in the view, such as parks or gardens. | 0–2 |

| Maximum vegetation height. | Maximum height of the vegetation, taking as reference the number of building stories. | 0–4 |

| Vegetation variety. | Heterogeneity of plants, trees, and shrubs. | 0–3 |

| Vegetation/soil contact. | Level to which it is possible to see the connection between vegetation and the soil of the ground or pots. | 0–3 |

| Vegetation/wall configuration. | Level of presence of vegetation with a wall behind in a view. | 0–2 |

| Wall/vegetation configuration. | Measurement of the presence of walls with vegetation behind in a scene. Only the upper parts of trees or plants are visible in this type of configuration. | 0–2 |

| Vegetation/vegetation configuration. | Quantification of the presence of vegetation followed by more vegetation in a view. | 0–2 |

| Floor/vegetation configuration. | Quantification of the built horizontal surfaces (e.g., sidewalks, tile floors, or streets) followed by vegetation in a view. | 0–2 |

| Natural and built integration. | Degree to which the vegetation and other natural elements are mixed or interlocked with the built elements. A clear separation of the built elements from the natural ones corresponds to the low level of this dimension. | 0–2 |

| Vegetation unity. | Degree to which the vegetation in the scene composes a continuous whole. | 0–2 |

| Mountain presence. | Quantification of the hills and mountains in a view. | 0–2 |

| Built/Human-Made Elements | Levels | |

| Built element proportion. | Quantification of the presence of all human-made elements in the scene. | 1–3 |

| Built element variety. | Heterogeneity level of the facades, walls, roofs, fences, and other built elements regarding their shapes, colors, and materials. | 0–2 |

| Architectural detail. | Quantitative complexity of built elements such as walls and roofs. | 0–2 |

| Floor/wall configuration. | Level of presence of built horizontal surfaces in contact with walls in a view. Angles of 90° are commonly present in such configurations. | 0–2 |

| Wall frontality. | Quantification of the walls positioned perpendicularly to the visual axis of the observer. A frontal wall blocking the observer’s view corresponds to the high level of this dimension. | 0–2 |

| Openness of the buildings. | Degree to which the built elements in a view present windows or other openings. | 0–4 |

| Dwelling presence. | Level to which houses or apartments may be appreciated in the view. | 0–3 |

| Street visibility. | Degree to which the streets are visible in the scene. | 0–2 |

| Car presence. | Quantity of cars in the view. | 0–2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de la Fuente Suárez, L.A.; Martínez-Soto, J. Relaxation and Fascination through Outside Views of Mexican Dwellings. Architecture 2022, 2, 334-361. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture2020019

de la Fuente Suárez LA, Martínez-Soto J. Relaxation and Fascination through Outside Views of Mexican Dwellings. Architecture. 2022; 2(2):334-361. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture2020019

Chicago/Turabian Stylede la Fuente Suárez, Luis Alfonso, and Joel Martínez-Soto. 2022. "Relaxation and Fascination through Outside Views of Mexican Dwellings" Architecture 2, no. 2: 334-361. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture2020019

APA Stylede la Fuente Suárez, L. A., & Martínez-Soto, J. (2022). Relaxation and Fascination through Outside Views of Mexican Dwellings. Architecture, 2(2), 334-361. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture2020019