Design and Disaster Resilience: Toward a Role for Design in Disaster Mitigation and Recovery

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (i)

- What can be learnt from examples of design-based responses to disaster mitigation and recovery?

- (ii)

- How can the skills needed to integrate design into disaster-risk management be developed?

2. Why Design?

3. Disaster-Resilient Design

- An analysis of the overall capacity, functioning, and relationships of the various components and systems that support communities, business, and industry

- Integrating new development projects within the limits of natural systems

- The planning and design of development and redevelopment patterns

- The design and patterns of open space

- The design of neighborhood and commercial districts

- Individual and building group design, including location, configuration, and coherence with building code and climate-change imperatives

- The location, design, and service capacity of community facilities and public infrastructure

- Design to facilitate emergency management functions, including egress and access, the location, safety, and capacity of emergency shelters used and staging areas

- Utilizing maintenance and rehabilitation management as important tools for climate-change mitigation and adaptation (p. 157).

- Architects have practical mind- and skill-sets which are of significant value in disaster mitigation and recovery, including the interdisciplinary understanding of science, engineering, technology, and materials; a spatial perspective on systems and patterns; creative problem-solving; planning, organizing, scheduling, and managing of—and working with—economic, social, emergency, legal, and governmental constraints.

- The spatial awareness, aesthetic, and design skills that good architects bring to projects, the ability to create beauty—and perhaps in the most unlikely environments—do add real value to psychologically distressed and demoralized individuals and communities. This may not be a high priority in the immediate aftermath of a disaster, when the overwhelming need is simply to provide emergency shelter for thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of displaced people. However, it is certainly very relevant in the transitional and permanent stages of rebuilding and resettlement.

- The poor, marginalized, and the distressed deserve the benefits of good architecture equally, if not more so, than the privileged few who can afford the aesthetic and functional benefits of commercial design practices. As Shigeru Ban said in his acceptance speech for the Pritzker Prize in 2014, ‘Architects are not building temporary housing because we are too busy building for the privileged people…. I’m not saying I’m against building monuments, but I’m thinking we can work more for the public’.

- There are no universal, one-size-fits-all solutions in resilient design. The most successful schemes, in terms of both their affordability and their benefits, are those built around intensive, sustained consultation with local people; the use, as far as humanly possible, of local materials and construction systems; and the employment of local people—often in situations where there is no other employment available—in the construction process.

- Design education has not served the field of disaster-resilient design well. None of the 15 architects interviewed by Charlesworth (2014) [17] had encountered the concepts and practices of public-interest design (Adendroth and Bell 2019) [31], humanitarian architecture (Zuckerman Jacobson and Ban 2014) [32], or any related fields. Indeed, they often lamented that the kind of professional attitudes and ambitions that were encouraged during their training mitigated against a view of architecture as a community service akin to public health or human rights law in medical and legal education. Instead, they came to the field of design and disasters as the result of personal and family values and career aspirations to expand their sometimes-limited disciplinary backgrounds.

… inevitably edits down the social context of any project: rushed site visits, often abstract briefs with no clear user or client to engage with, and compressed timescales all mitigate against development of the skills required for socially engaged architecture. In addition, the standardized diet of juries, long nights, and isolation from other disciplines further consolidates the de-socialization of architecture students as they are admitted into the rituals of the tribe. A move towards a more socially engaged practice therefore needs a distinct shift in the processes, projects, and ethos of architectural education.

4. Learning for Disaster-Resilient Design

- The importance of critical reflection on design for disasters and displacement as the ‘new normal’

- The desirability (or otherwise) of a competency framework for curriculum development in the field of design for disaster mitigation and recovery

- The practice of designing for a much wider range of clients than in commercial architecture, many of which are marginalized and may have few resources

- The ethical and political dimensions of design as a break with traditional ‘modernist’ practice in the profession

- The importance of teaching ethics in design education

- The challenge of teaching the values and skills underlying socially engaged co-design practices

- The value of integrating teaching and learning with research—co-produced, evidence-based practice

- Pedagogical challenges such as integrating conceptual knowledge of key issues through field-based studies and simulations.

- Integrating systems thinking and design thinking as pedagogical and professional tools.

- The value of developing transferable, 21st-century skills and predispositions suitable for employability in the disaster and humanitarian fields, especially for working with vulnerable people living under hardship.

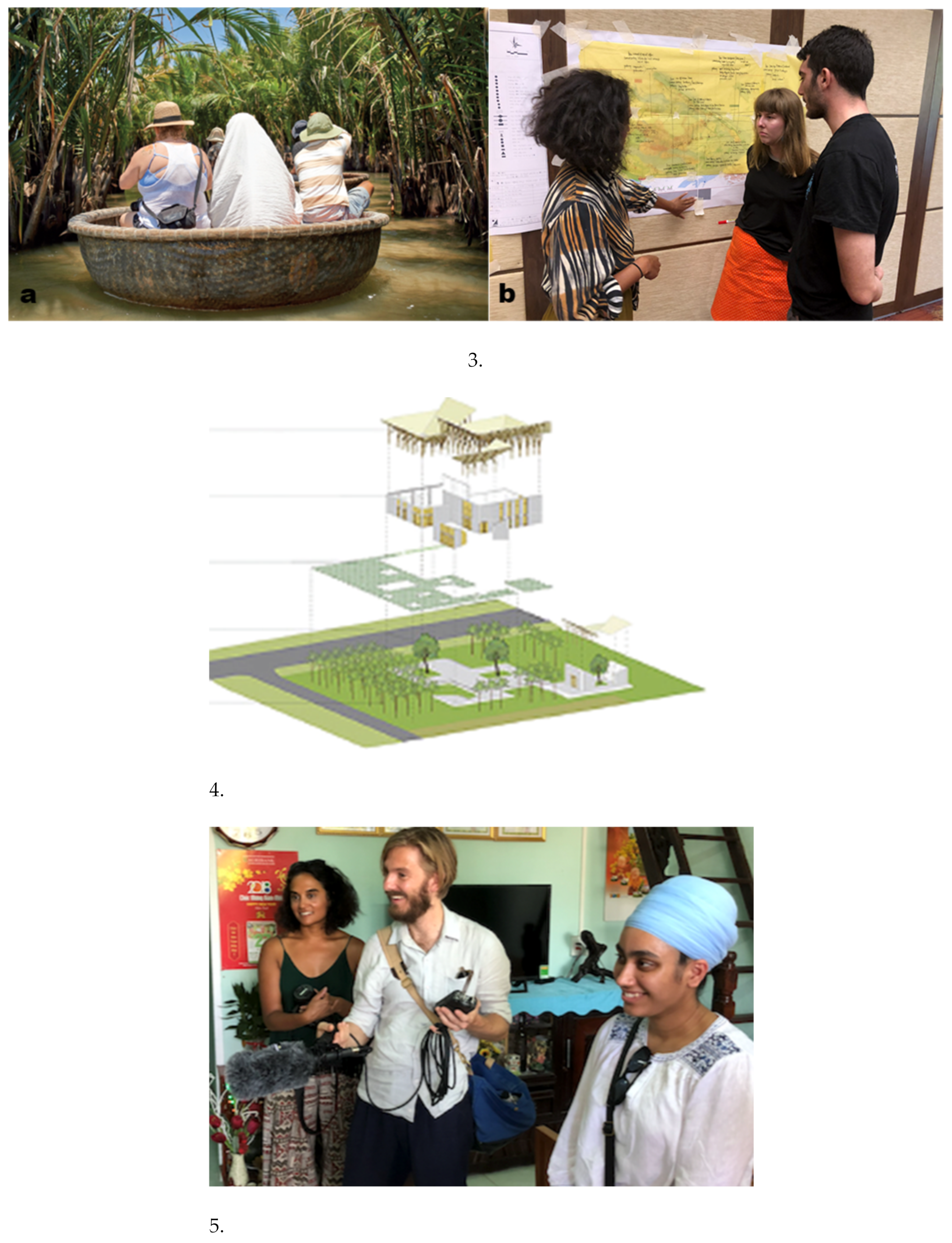

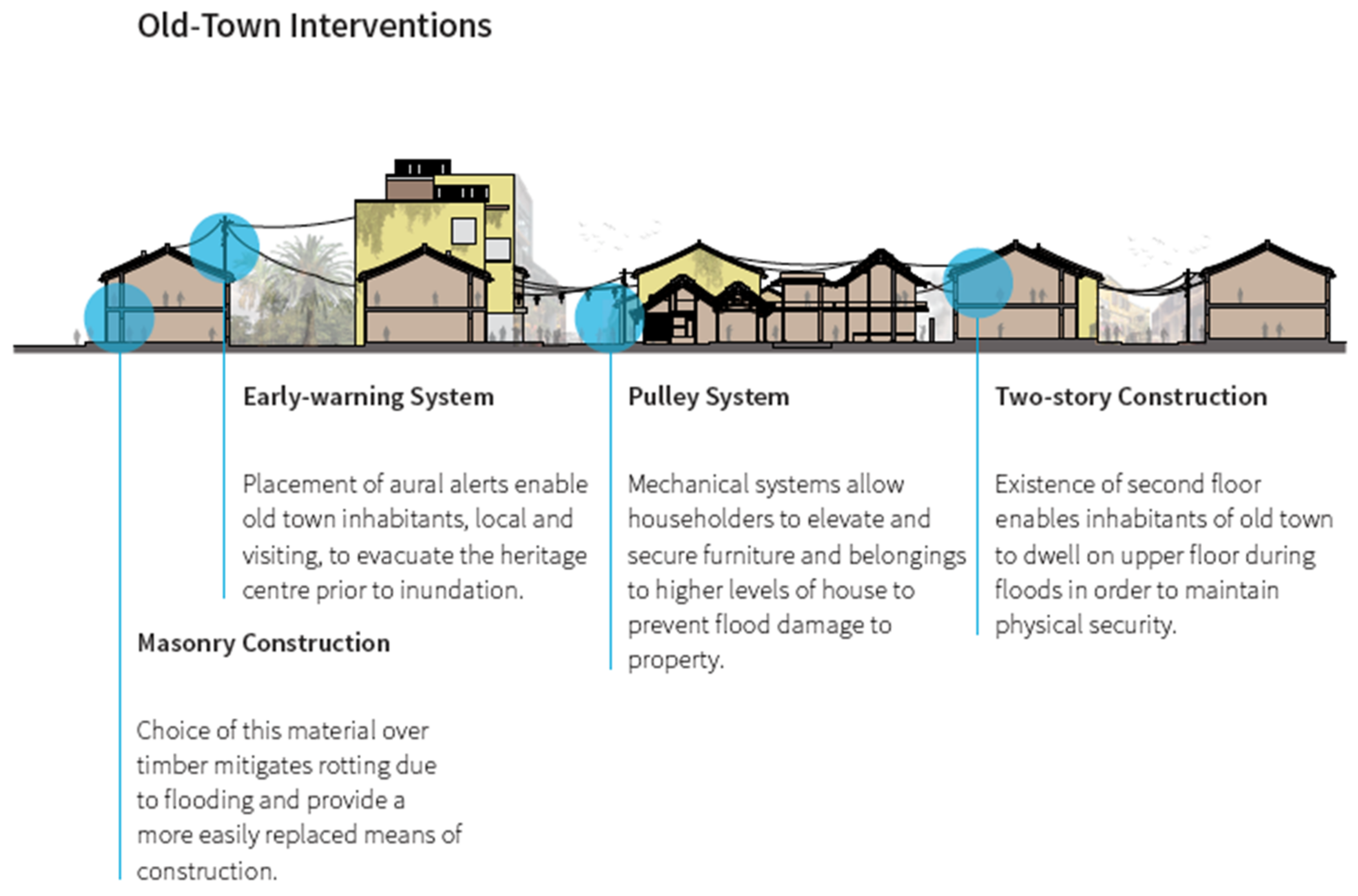

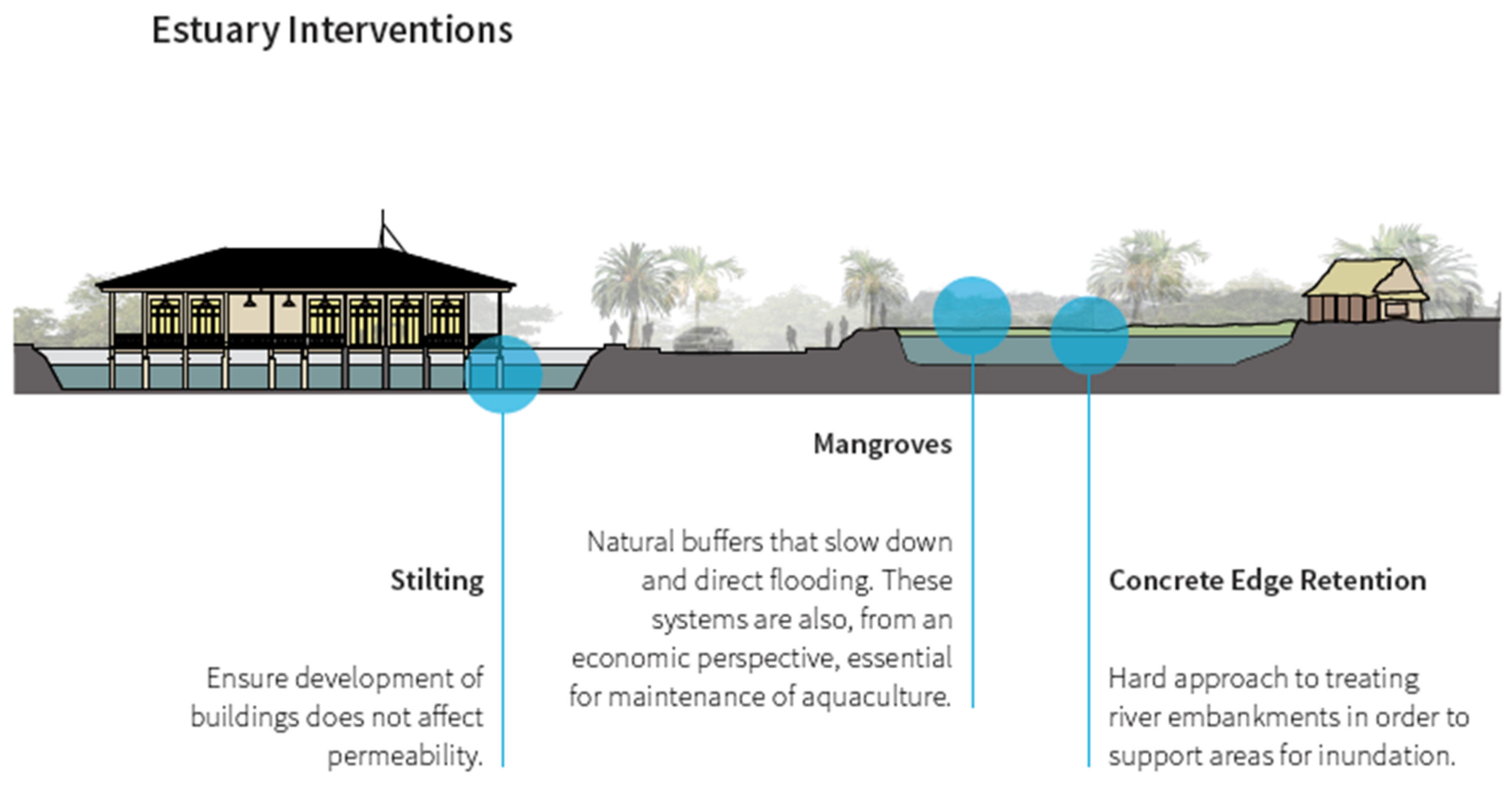

5. Climate Change, Design, and Development Study, Hội An, Vietnam

- Synthesizing knowledge from a variety of scientific and community-based sources on climate change, and the links between climate change and disasters

- Evaluating key strategies of climate-change adaptation and disaster-risk reduction, and their differences and convergences

- Interpreting and analyzing the implications of climate change and disasters for the built environment, in parts of the Asia–Pacific region, from diverse perspectives and sectoral linkages

- Working effectively with others in a field-based situation and demonstrating social, intercultural, and environmental awareness

- Communicating using diverse formats and strategies to engage with a range of stakeholders.

6. Conclusions

- International, government, and community agencies are struggling to implement effective strategies for disaster-risk reduction and for planning long-term recovery after disasters. The central challenge these agencies face is the development of policies and practices for reducing the vulnerabilities that prevent communities from becoming more disaster-resilient. Design can be seen as a critical bridge in planning for disaster mitigation and recovery.

- There is a practice–theory gap between the community-led processes needed for long-term recovery and the product-delivery culture that characterizes many shelter and settlement programs. The result is often a ‘one size fits all’ approach to housing, with insufficient attention paid to the aspirations of the people most affected and the infrastructure needed.

- The skills of experienced system and design thinkers, such as architects, urban planners, and landscape architects), are seldom employed in the disaster-risk-management field, despite their demonstrated capacity to work with communities and to develop integrated spatial responses to guide both disaster-risk reduction and long-term rebuilding after a disaster. Developing design solutions at housing and settlement scales, e.g., preparing house designs and community master plans, is the core competency of architecture. However, this expertise has been neglected and the number of built-environment professionals such as architects equipped to respond in such situations is still very low.

- While there is an innate conservatism in most design degrees in terms of dealing with critical social challenges and crises, specialized masters degrees incorporating disaster-resilient design are emerging, and are training the next generation of disaster, humanitarian, and development professionals.

- The paper has outlined the contributions of design as a disciplinary and operational tool to deal with many of the social, environmental, and economic crises now being faced. However, a reorientation of design education is needed so that it addresses core disaster-risk-management concepts, such as vulnerability, urban resilience, climate-change adaptation, risk-based design, and scenario and community planning. Otherwise, it will not achieve its potential value in enhancing disaster resilience.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Munich Re. Relevant Natural Catastrophe Loss Events Worldwide 2019. 2020. Available online: https://www.munichre.com/en/company/media-relations/media-information-and-corporate-news/media-information/2020/causing-billions-in-losses-dominate-nat-cat-picture-2019.html (accessed on 2 August 2020).

- IDMC (Internal Disaster Monitoring Centre). Global Report on Internal Displacement 2020; IDMC, 2020; Available online: https://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2020/ (accessed on 2 August 2020).

- IDMC (Internal Disaster Monitoring Centre). Assessing the Impacts of Climate Change on Flood Displacement Risk; IDMC, 2020; Available online: https://www.internal-displacement.org/publications/assessing-the-impacts-of-climate-change-on-flood-displacement-risk (accessed on 2 August 2020).

- Cadman, E. Insurance Industry Calls for Action to Mitigate Climate Risk as Australia Bushfires Widen; Bloomberg News: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-01-08/deadly-australia-fires-spur-calls-to-mitigate-disaster-risk (accessed on 9 February 2020).

- Bojic, D.; Baas, S.; Wolf, J. Governance Challenges for Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Change Adaptation; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Geis, D. By design: The disaster resistant and quality-of-life community. Nat. Disaster Rev. 2000, 1, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldunce, P.; Beilin, R.; Handmer, J.; Howden, M. Framing disaster resilience. The implications of the diverse conceptualisations of “bouncing back”. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2014, 23, 252–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D.E. Resilience and disaster risk reduction: An etymological journey. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 13, 2707–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fisher, T. Designing to Avoid Disaster: The Nature of Fractal-Critical Design; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Mathiesen, C.; March, A. Establishing Design Principles for Wildfire Resilient Urban Planning. Plan. Pract. Res. 2018, 33, 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.; Choy, D.L. Adapting Australian coastal regions to climate change: A case study of South East Queensland. In Climate Change and the Coast: Building Resilient Communities; Glavovic, B., Kelly, M., Kay, R., Travers, A., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; pp. 269–284. [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth, E.; Ahmed, I. Sustainable Housing Reconstruction: Designing Resilient Housing after Natural Disasters; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan, J. Seeking an interoperability of disaster resilience and transformative adaptation in humanitarian design. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2018, 9, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A. Design by Resilience; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, R. Wicked problems in design thinking. Des. Issues 1992, 8, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T. ‘Design Thinking’ Is Changing the Way We Approach Problems. 13 January 2016. Available online: http://www.universityaffairs.ca/features/feature-article/design-thinking-changing-way-approach-problems (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Charlesworth, E. Humanitarian Architecture: 15 Stories of Architects Working after Disasters; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot-Ortega, J. Urban Design as Problem Solving: Design Thinking in the Rebuild by Design Resiliency Competition. Master’s Thesis, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA, 2010. Available online: https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/98931 (accessed on 26 July 2020).

- Shaw, R.; Rahman, A.; Surjan, A.; Parvin, G. (Eds.) Urban Disasters and Resilience in Asia; Butterworth-Heinemann/Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Landscape Architects. Resilient Design; American Society of Landscape Architects: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.asla.org/resilientdesign.aspx (accessed on 9 August 2020).

- Sanderson, D.; Jayden, J.; Leis, L. (Eds.) Urban Disaster Resilience; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, D. The game changes: ‘Disaster Prevention and Management’ after a quarter of a century. Disaster Prev. Manag. Int. J. 2016, 25, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, L.; Donovan, J.; Buur, J. Challenging industry conceptions with provotypes. CoDesign 2013, 9, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vandenbroeck, P. Working with Wicked Problem; King Baudouin Foundation: Brussels, Belgium, 2012; Available online: https://www.kbs-frb.be/en/Virtual-Library/2012/303257 (accessed on 5 July 2015).

- Davis, I. Shelter after Disaster, 2nd ed.; Oxford Polytechnic Press: Oxford, UK, 1978; Available online: https://www.ifrc.org/Global/Documents/Secretariat/201506/Shelter_After_Disaster_2nd_Edition.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2018).

- Daly, P.; Feener, R. (Eds.) Rebuilding Asia Following Natural Disasters: Approaches to Reconstruction in the Asia-Pacific Region; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2019; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/globaltrends2019/ (accessed on 2 August 2020).

- Wilson, A. Resilience as Means of Mitigating Climate Change 2014. Available online: https://www.resilientdesign.org/resilience-as-means-of-mitigating-climate-change/ (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Resilient Design Institute (nd). What Is Resilience? Available online: https://www.resilientdesign.org/defining-resilient-design (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Evans, G. Launch of Humanitarian Architecture; Australian Institute of Architects, Victorian Chapter: Melbourne, Australia, 12 August 2014; Available online: https://www.gevans.org/speeches/speech549.html (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- Adendroth, L.; Bell, B. Public Interest Design Education Guidebook: Curricula, Strategies, and SEED Academic Case Studies; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman Jacobson, H.; Ban, S. Shigeru Ban: Humanitarian Architecture; Distributed Art Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Awan, N.; Schneider, T.; Till, J. Spatial Agency: Other Ways of Doing Architecture; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Till, J. Architecture after Architecture; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; Available online: http://www.jeremytill.net/read/130/architecture-after-architecture (accessed on 2 August 2020).

- Bristol, G. The last architect. In Proceedings of the Silpakorn Architectural Discourse 3rd Mini-Symposium, Bangkok, Thailand, 18–19 March 2004; Available online: https://www.academia.edu/7732516/The_Last_Architect (accessed on 9 July 2018).

- Griffiths, R. Knowledge production and the research-teaching nexus: The case of the built environment disciplines. Stud. High. Educ. 2004, 29, 709–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Jones, T. Mind the Gap! Post-Disaster Reconstruction and the Transition from Humanitarian Relief; RICS: London, UK, 2006; Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/publications/view/9080 (accessed on 24 July 2020).

- Lloyd-Jones, T.; Kalra, R.; Mulyawa, B.; Theis, M.; Wakely, P.; Payne, G.; Hal, N. The Built Professions in Disaster Risk Reduction and Response: A Guide for Humanitarian Agencies; MLC Press, University of Westminster: London, UK, 2009; Available online: https://www.ifrc.org/PageFiles/95743/B.a.07.Built%20Environment%20Professions%20in%20DRR%20and%20ResponseGuide%20for%20humanitarian%20agencies_DFDN%20and%20RICS.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2020).

- Owen, D.; Dumashie, D. Built Environment Professional’s Contribution to Major Disaster Management. In Proceedings of the FIG Working Week, Hong Kong, China, 13–17 May 2007; Available online: https://www.fig.net/resources/proceedings/fig_proceedings/fig2007/papers/ts_1h/ts01h_03_owen_dumashie_1531.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2020).

- Cage, C.; Hingorani, D.; Jopling, S.; Parke, E. Building relevance: Post-disaster shelter and the role of the building professional. In Proceedings of the Background Paper for Conference of the Centre for Development and Emergency Practice (CENDEP); Oxford Brookes University: Oxford, UK, 18 September 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T. A new paradigm for design studio education. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2010, 20, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurairajah, N.; Palliyaguru, R.; Williams, A. Incorporating disaster management perspective into built environment undergraduate curriculum. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Building Resilience, Kandalama, Sri Lanka, 20–22 July 2011; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333131988 (accessed on 31 July 2020).

- Acar, E.; Yalçınkaya, F. Integrating disaster management perspective into architectural design education at undergraduate level—A case example from Turkey. In Proceedings of the 5th World Construction Symposium 2016, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 29–31 July 2016; pp. 284–293. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303988576 (accessed on 28 March 2020).

- Till, J. Foreword. In The Routledge Companion to Architecture and Social Engagement; Karim, F., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; Volume xxvi–xxviii. [Google Scholar]

| Phases in the Study | Learning Activities | Pedagogical Principles |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Site familiarization |

|

|

| 2.Consultations and workshops with key local experts and stakeholders |

|

|

| 3.Field investigations and data analysis |

|

|

| 4.Design and planning |

|

|

| 5. Presentation and reporting |

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Charlesworth, E.; Fien, J. Design and Disaster Resilience: Toward a Role for Design in Disaster Mitigation and Recovery. Architecture 2022, 2, 292-306. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture2020017

Charlesworth E, Fien J. Design and Disaster Resilience: Toward a Role for Design in Disaster Mitigation and Recovery. Architecture. 2022; 2(2):292-306. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture2020017

Chicago/Turabian StyleCharlesworth, Esther, and John Fien. 2022. "Design and Disaster Resilience: Toward a Role for Design in Disaster Mitigation and Recovery" Architecture 2, no. 2: 292-306. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture2020017

APA StyleCharlesworth, E., & Fien, J. (2022). Design and Disaster Resilience: Toward a Role for Design in Disaster Mitigation and Recovery. Architecture, 2(2), 292-306. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture2020017