Abstract

The life of the 5th Duke of Portland is a story about the mental obsession to find a haven of absolute stillness, a worry-free place, and somewhere to feel safe (Pl L1/2/8/3/13: Four letters to Fanny Kemble, 1842–1845. In these letters, the 5th Duke refers to the subsoil as “shelter” and the “only safe place”, found in Manuscripts and Special Collections, Archives Nottingham University). Perhaps it is there, in the space that unfolded away from the visible world, that he found the strength to overcome his difficulties and to understand the scale of space and its intangibility; he was aware of the relationships and interaction between the human body, inhabited space, and the mind, and this information helped him in his hiding process. After his appointment as the heir to his immense estate, a series of investments on an unprecedented scale began almost immediately, which have been considered, both technically and conceptually, to be pioneers of domestic and landscape architecture during the nineteenth century. Welbeck Estate represents the construction of a double city, one that is visible and another that is concealed, but it is also a reflection of how our body and our mind interfere, dialogue, and create an architectural space that is framed in a cognitive process. Space and time were unfolded and folded into themselves in order to build this fascinating scenery, which represents the duke’s life.

1. Introduction: 5th Duke of Portland. Invisibility Strategies

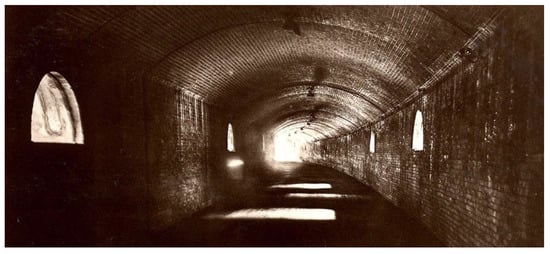

The story of the transformation of Welbeck Estate begins at a decisive stage during the succession of John William Cavendish-Scott-Bentinck, Marquess of Titchfield, as the 5th Duke of Portland in 1845. It was he who was responsible for designing and building the mysterious underground spaces for which these lands are known for and that have recently been nominated for recognition at the Venice Biennale of Architecture. Thousands of tunnels were hewn out of Welbeck’s subsoil by the duke, creating a fascinating underground labyrinth that is more than 10 km in length and that remains hidden beneath the surface of his estate in Sherwood Forest, Nottinghamshire, England.

Legend and myth have woven the history of this enigmatic place, which is profoundly marked by the extravagant personality of its owner. He was a figure who, thanks to his trajectory and status, is wrapped in a halo of exceptionality, fictitious or not, deserved or not, which elevates him, without a doubt, to the category of genius. In the archives at the University of Nottingham that were consulted during this investigation, he is referred to as the underground man, the mole, and the burrow duke several times, highlighting his invisible and solitary lifestyle. His manuscript correspondence reveals a fascinating personality and a most exciting archetype of an English aristocrat. In one of the very few letters found that was written by the 6th Duke of Portland referring to the unique life of his predecessor, it is narrated that, as he was arriving at Welbeck Abbey for the first time during Christmas of 1879, just after the death of the 5th Duke, he found that, in order to access the house, they had to place temporary boards over a swamp of rubble in order to access the building. As they entered the abbey that day, the reception room had no floor; it had collapsed. The late duke was no doubt so absorbed in his ambitious underground task that he forgot about what was happening on the surface. He had a curious obsession with concealment and camouflage that led him away from human contact in order to immerse himself in the depths of his own land for most of his life (reference is made to the 6th Duke of Portland and to the singular life of his predecessor, stating that upon first arriving at Welbeck Abbey during Christmas 1879, just after the 5th Duke’s death, he found that in order to gain access to the house, they had to put temporary boards to the house to save a swamp of infiltrated waters and that when entering the Abbey that day, the reception room had no floor and a large tree peeked out from the basement—from FRASER, W (1910): County Pedigrees: Nottinghamshire, p. 53, W. P. W Phillimore Ed.).

Many affirmations have surrounded the duke’s personality, multiplying in number and fantasy, to create an eccentric tale of his life that has managed to endure to this day despite remaining unconfirmed. It is said that he spent most of his life inside his home, concealed within a five-room suite, and that he was connected to the rest of the world by a system of corridors and caves that stretched out right under his estate.

It is said that this ingenious maze made many of his extravagant requests possible, such as having a freshly roasted chicken at any time of day or night and traveling to London without being seen, which could be achieved by using the tunnel that extended to Worksop Station tens of miles away from the abbey. Servants who ever encountered him in the corridors were forbidden to look into his eyes and had to leave immediately whilst facing the wall. Remarks and anecdotes, some of which we have been able to confirm in the correspondence that was consulted in the family archives and others of which are a part of the constellation of the ideas about this man, have helped us construct the biography of this enigmatic figure.

William John Cavendish Bentinck Scott was born in 1800, the second son of the 4th Duke of Portland, and was also known as Lord John Bentinck. At the age of 24, he became the Marquis of Titchfield and the future heir to the Duchy as a result of the unexpected death of his eldest brother. With no worries other than horses, racing, and hunting, he resigned from his position as a Member of Parliament for King’s Lynn and handed over the position to his younger brother, Lord George Bentinck, claiming that his ill health prevented him from participating in public affairs. This is the first indication of the difficulty he had in assuming the expectations of his social standing, and it is here that he decided that, from this moment onwards, he would disappear from the public eye forever and, instead, begin a life of introspection, in which architecture would play a fundamental role [1].

He was a solitary traveler; after leaving the army, he spent some time travelling around Europe on his own. Even when he moved to Italy, he did so unaccompanied. All of the preparations for the trip were made in advance by his trusted staff. When it became known that he had arrived in the Italian capital, the whole of the aristocracy requested a formal visit with the duke. The attention was so disproportionate compared to his habit of solitude that he decided to pull out of Rome’s social life, probably to visit the subterranean structures of Villa Adriana. In the archives that were consulted at the University of Nottingham, there are notes in which the duke himself, who was overwhelmed and stunned by the number of social visits that was required of him, publicly thanks the interest shown. However, in the end, he would spend a few reclusive weeks in the Roman city and then later return to Paris for a couple of days before immediately moving on to Calais and then back to London. These journeys undoubtedly constituted the encounter of something the duke was looking for, i.e., the discovery of a space, a hole, a burrow to build and dedicate the rest of his life to.

Other than having an overwhelming enthusiasm for travelling and opera, there are not many references to his life during these years, which is reflected in a series of letters written in 1842 to the Kemble family which show his kind appreciation towards the world of scenography. Years later, with the death of his father and his appointment as the 5th Duke of Portland, he decided to retire from public life and dedicate himself exclusively to the management of his properties in London, Scotland, and especially to undertake his plans at Welbeck Estate, an ambitious task that, in time, would become his only obsession. The story of the transformation of this beautiful landscape entered a decisive stage with his appointment. He would be remembered for having led one of the largest projects of underground domestic architecture in the country and for having dedicated his life to the design and construction of the mysterious underground spaces, or arguably intangible spaces, that are hidden beneath the surface of this incredible place [2].

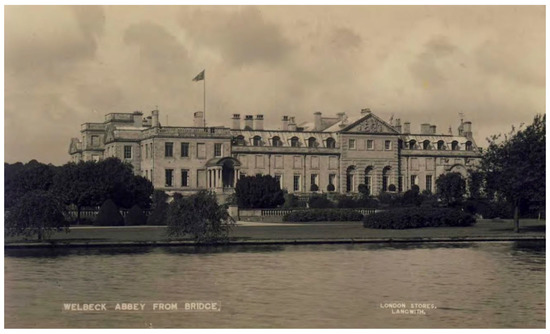

The duke always showed great interest in the social and technological advances during his time, an attitude surely learnt from his own father, the 4th Duke of Portland. His enormous creative qualities made him a gadget inventor, which allowed him to create a life surrounded by the idea of concealment. His inventions favored his own invisibility, from his horse carriage to his own bed. The network of tunnels that are hidden under Welbeck built a kind of scenery for life in which its actors, spaces, and objects could appear and disappear in a ritual launched day after day. He was a sort of magician whose innate technical virtuosity is put at the disposal of his only obsession: to live without being seen. Even to this day, when visiting this place, you can perceive his 34-year reign, from 1845 to 1879, which made Welbeck a national benchmark as a place full of life and prosperity (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Welbeck Abbey, 1860. (Archives Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham, Nottingham).

There are many doubts surrounding the true underlying causes of his obsession with camouflage and concealment; amongst the family papers, we find some letters that could justify this attitude. Many have been the queries, but very few have documented reasons of what many critics have described as a psychological disturbance. The first reason could be for his own personal pleasure to hide, the enjoyment of technical novelties and admiration towards them, as well as an interest in the knowledge and application of these techniques to build a hidden side to his life (Figure 2). However, the second reason could be an incessant desire to find himself; an erratic (or not) path of introspective search, to reach a state of mental peace, while understanding that the key was not in the exterior, but in the interior space [3].

Figure 2.

The Portland Collection, Harley Gallery, Welbeck Estate. Invisibility strategies. Objects built by the 5th Duke of Portland to avoid being seen. Secret doors and trapdoors in the abbey’s floors and ceilings. (Photos taken by the author in 2015).

It seems curious to have used correspondence as the only form of contact with family members, as well as his circle of agents, managers, foremen, and servants. Thanks to the many letters that are preserved in his archives, we know of his health problems. He suffered a skin disease in the form of acute psoriasis, which was subsequently aggravated by arthritis and terrible neuralgia, leading him away from light and noise.

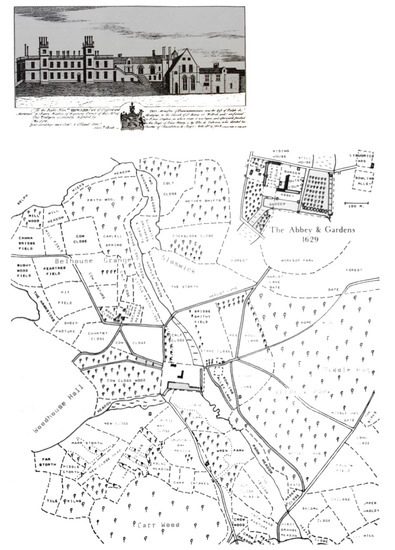

His curious obsession led him to invent, with great ingenuity, a whole series of spaces and gadgets, building up a kind of invisibility and deception game. A horse carriage was specially designed for him to move around in without being seen, with trapdoors, double doors, a communication system for the staff, unattainable passages, and secret shortcuts. They all built a parallel world, a background in which to establish his life, reflected in the way he dressed, the objects and gadgets designed around his lifestyle, the spaces and corridors hidden under the abbey, and the tunnels and caves built under the whole landscape. In all of these, invisibility and delusion are a prominent aspect. He always sneaked around, appearing here and there without any warning, moving through a functional and suggestive space that he managed to build for himself (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Welbeck Estate, 1629. Two centuries before the duke’s appointment. Literal inscription at the top of the plan: “The Abbey and Gardens, after W. Senior, 1629”. The buildings are those that make up the abbey. The upper drawing is by Samuel Buck, 1726. On the left, the West Wing which would become the duke’s Oxford Wing after the extension and on the right, the old chapel. (Archives Manuscripts and Special Collections. University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK).

In the archives of the University of Nottingham, we were able to verify that his first love was never reciprocal, which led him to a state of rejection towards women and extended to humanity itself (Pl L7/23/6/18. Pencil notes regarding the Druce Case and sketches of skylights to Welbeck tunnels. Along with the drawings, the duke notes on these papers some key words that help this interpretation “black light” “black earth” along with others that appear crossed out “surface”, in Manuscripts and Special Collections. Archives Nottingham University). It is said that he rarely walked outdoors in public, and when he did, it was always at night. He never returned a greeting and often accused people of their intrusion into his domains. There is no doubt that he preferred to wander beneath the ground, to use that other place, that strange unfolded space he had built for himself. Architectural mechanisms, devised by what might be called genius, and secrets were used to achieve invisibility. Strategies that gradually made him become a fantasy character, a more and more desirable icon, masked and always hidden [4].

The curious room that he used during the day shows his wit. It was equipped with a trapdoor on the floor, by which he could descend underground to wander through the tunnels without anyone noticing his absence (Figure 4). The trapdoor had incorporated a reversible opening and closing system, which meant he could walk unnoticed beneath his estate and reappear in the abbey as mysteriously as he had left it (A clear introduction of the Bentinck’s family and 5th Duke of Portland as a figure of extravagance, with an interesting life-timeline and family tree. The text describes an ingenious room that he used during the day, from which he descended underground to wander through the tunnels without anyone noticing his absence, in ARCHARD, C (1907): The Portland Peerage Romance, p. 62, Greening London Ed.). In addition, the room also had another door leading to the anteroom; it was this that served as a communication link to his service. He wrote the orders that had to be carried out on two small mailboxes on the door. The duke wrote down what he needed on paper and deposited it in the mailbox, which opened from the anteroom. Then, a bell rang, to signal that a certain order should be executed.

Figure 4.

Underground Welbeck, tunnel n° 1. It is the longest tunnel, connecting the Riding School to the South Lodge, 1870. (Archives Manuscripts and Special Collections. University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK).

The bed in this room had also been designed by him and built in the estate workshops. Its structure was an immense square construction, a kind of box in the middle of an empty room; a huge piece of furniture, a hideout, a place of intimacy. The bed had large vertical boards arranged in such a way that, when they unfolded, it was impossible to know if the bed was occupied by its owner. His life was full of concealments, traps and deceptions, objects and spaces, as well as truths that pretended to be lies and lies that pretended to be truths. The result was a camouflaged room, a cluster of ticks practiced by a human and objects that surrounded his behavior [5].

William John Cavendish Bentinck Scott, fifth Duke of Portland, died in 1879, having lived to nearly 80 years old. He spent his last few years hiding amongst his people, concealed in the depths of his world, where he died strolling on a rainy December afternoon. That was his last journey, a last immersion as a farewell (At the close of the Victorian era, privacy was power. The extraordinarily wealthy 5th Duke of Portland had a mania for it, hiding in his carriage and building underground tunnels to stroll avoiding being seen. This text evokes an era that blurred every fact into fiction, in which family secrets and intangibility identities pushed class anxieties to new heights, in EATWELL, P (2015): The Dead Duke, His Secret Wife, and the Missing Corpse: An Extraordinary Edwardian Case of Deception and Intrigue, p. 32, Liveright Publishing Corporation).

2. Methodologies for Hiding: Architectural Discuss

John William Cavendish-Scott-Bentinck, the 5th Duke of Portland, transformed his home into an extension of his own personality and behavior. Even at the risk of transmitting information that may be frivolous, we have tried to show a certain attitude of exceptionality in his way of life. At Welbeck Estate, personality and architecture are intertwined, obsession and engineering, showing the indelible mark of its owner. It is a tailor-made set, full of objects and strategies that cannot be generalized. His home, and by extension his estate, became an authentic laboratory of architectural experimentation where he could leave his own non-transferable mark. He turned his estate into a gigantic invisibility mechanism, transformed his property into a double city, which was visibly constructed with materials from earth’s crust and installed into the landscape. Unfolded and inverted, hidden in a lower strata, it became part of a submerged world, immaterial and invisible. The Duke used an extensive repertoire of tactics and hidden spaces, as well as technical solutions of disguise learnt from his love of opera [6].

Welbeck Estate is unveiled as a constructed scenery, a magical ritual of approach and invisibility that turns fantasy into reality. This is a mysterious city, as a top hat or a theater stage, in which dreams and secrets overlap to create an indivisible part of everyday reality. Seeing this city in action is a fascinating experience, attending with naturalness and emotion to unexplainable situations, things never seen before that defy all logic. A halo of mysticism and magic typical of intangible spaces; those that can neither be touched, nor seen, nor smelled, but perceived with other senses that go beyond rational thought; a phenomenological architecture that is born out of the consciousness of each person [7].

It is fascinating how the duke made possible the dream of owning the same house with several different styles and time periods simultaneously, concentric and hidden in their interstices, or, better yet, different houses that converge into one. The result was an architecture communicated by temporary spaces, labyrinths, and corridors, which allow us to decide the desired occupation at any moment.

Holes, gates, hollows, dips, roads, and shortcuts intersect to lead to the same place or to different places, which only make sense when drawn together. We could disappear through a 19th century hole and come out in the 21st century, or the other way round as if we were in a time tunnel with which we could reach the origins of the family itself. These doors led to unusual spaces, tunnels were used for nobility and its servants, and mechanisms and scenic devices were capable of sheltering, which was surprising and entertaining to the monarchy itself (JACKS, L (1881): The underground rooms. The great Houses of Nottinghamshire, pp. 46–62, British Library Ed. This essay is a collection of columns from The Nottingham Journal. His visit to the Welbeck Estate and his admiration for the underground connections and rooms hidden beneath the estate are accurately described. Words such as holes, doors, gaps, depressions, paths, and shortcuts are commonly used in writing).

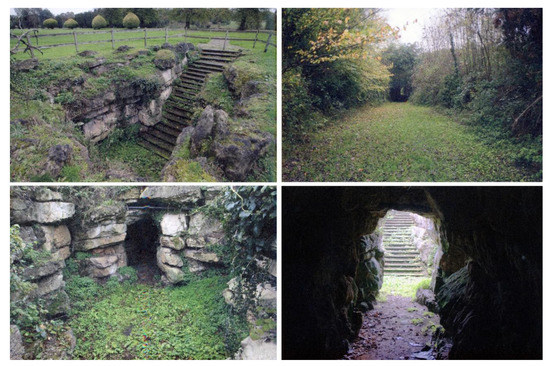

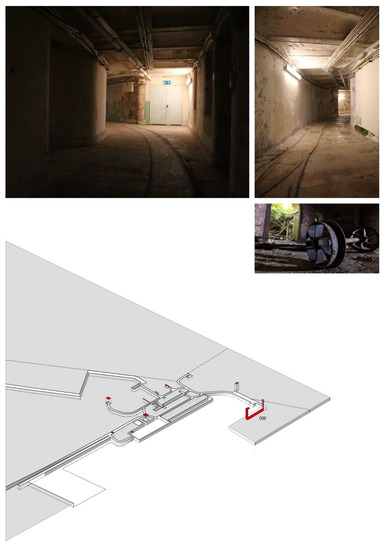

In October 2015, with the help of Robert Mayo, Development Director of Welbeck Estates Company LTD, I was allowed to visit Welbeck Estate and the incredible work done to it. I now realize that everything written about the magnitude of the 5th Duke of Portland’s personality, and the incredible feeling when travelling through all that is hidden under the soil of this city, is not exaggerated (Figure 5). That same year, Venice’s Biennale of Architecture took place and Welbeck was nominated for its exceptional characteristics. Koolhaas, himself, at the inaugural conference of the exhibition asked two open questions regarding why the duke had this strange obsession with invisibility and what led him to undertake this incredible enterprise [8].

Figure 5.

Walks through Welbeck Estate. Burrows and tunnels. (Photographs taken by the author, October 2015).

Welbeck is about 10 km away from Worksop, and as we approach it, its enormous extent and beauty dawns on us. The architecture is a mixture of styles constructed during different periods, classic and Italian, with an imprint underneath that has been devoid. Welbeck Estate occupies about 60,000 square meters of land and extends to the boundaries of Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire (Figure 6). It is the most prosperous territory of all Dukeries, a district consisting of four ducal properties: Clumber House, of the Dukes of Newcastle; Thoresby, belonging to the Dukes of Kingston; Worksop Manor, belonging to the Dukes of Norfolk; and finally, Welbeck Abbey, home to the Dukes of Portland.

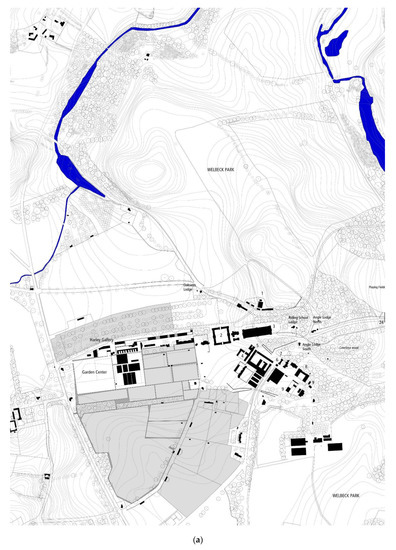

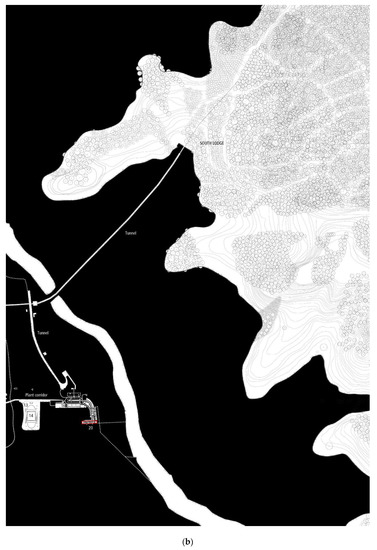

Figure 6.

(a) Welbeck Estate, 2015. Scale 1:8000. Cartography drawn by the author based on the documentation provided by the British Cartographic Society, 2015. 1. Elephant Hut. Garages and offices_ 2. Future School of Architecture (old stables)_ 3. Editorial Funds (former Riding School)_ 4. Bursars Court_ 5. Strangers Yard_ 6. Wood Yard Lodge n° 1_ 7. Old School_ 8. Lower Motor Yard_ 9. College Workshop. (b) Welbeck Estate, 2015. Scale 1:8000. Cartography drawn by the author based on the documentation provided by the British Cartographic Society, 2015. 10. Shrubbery Lodge_ 11. New Kitchen Lodge_ 12. New Science Block_ 13. Rose Corridor_ 14. Sunken Garden_ 15. Old Kitchen Block_ 16. Ballroom_ 17. Library and Chapel_ 18. The Virgin’s Block_ 19. Old Wing_ 20. Oxford Wing_ 21. Summer House_ 22. Cricket Pavilion_ 23. Nissen Hut_ 24. Gate Lodges.

Welbeck Abbey retains a beautiful history, having had various owners over time. Initially retained by Sweyn Saxon before the Norman invasion, it became after the conquest Chuckney’s manor house, who founded the abbey, dedicating it to St. James during the reign of Henry II. Four hundred years later, the abbey was partially destroyed along with other similar institutions throughout the country. After several decades in which we have been able to identify several owners, it finally fell into the hands of the Cavendish family, who ended up turning it into a noble mansion. As proof of the importance, the property acquired from this moment took place on two visits between 1619 and 1663, captured in the family archives. On one occasion, King James visited Sir William Cavendish, and, later, King Charles I himself was invited for a few days of entertainment at Welbeck Abbey; some notes speak of such an excess at the banquet, it had never been seen before in England.

Especially interesting are the paragraphs dedicated to the description of hydraulic elevators. A technically complex mechanism was used for the vertical movement and manipulation of large furniture and heavy objects, as well as to link the kitchens to the dining room and bedrooms. This network of vertical ducts continued under the main building, extending all over the territory through the underground tunnels where rails were arranged for the displacement of this curious domestic machinery. Inside the abbey, this contraption’s functioning and size is comparable to that of a narrow-gauge streetcar, ending at the vertical communication systems, to where the small carriages were driven to carry away food. Iron cabinets were arranged in each anteroom to keep the food warm until it was required for consumption in the adjoining rooms [9].

We are undoubtedly in the presence of one of the 5th Duke of Portland’s most ingenious inventions; it did not only supply the abbey with warm dishes, but also facilitated the entry and exit of other objects (furniture, works of art, fuel, etc.) and service personnel, without interfering with the building’s normal running. Without a doubt, his mind was exceptional; it was the mind of a genius, of a wizard who pursued and insisted on the discovery and surprise of staging. It was the mind of an architect, of an engineer who ingeniously projected pieces for this complex stage machinery.

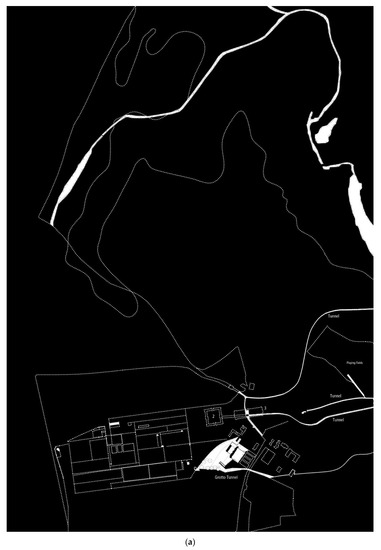

This underground passage, which connects the abbey to the old Riding School, is entered by using a trapdoor, an architectural shortcut that is opened by a huge crank (Figure 7). Only those who have had access to this room have an idea of its proportions, its richness, and the amazing sensation that one has when accessing it. During the time of the duke, it was used as a riding school but, currently, its use is more noble, serving as a museum and art room, in which long threads of selected paintings are hung. This room must have showcased hundreds of pictures, treasured portraits, and landscapes by famous artists. The floor is polished oak, very dark and shimmering, and the ceiling, white and thick, was carved to represent a glorious intense sky.

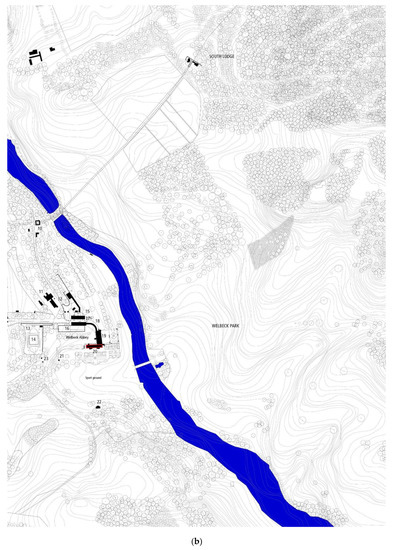

Figure 7.

Welbeck Abbey, 2015. Tunnels underneath the building. Rails on the ground to transport food (Upper). Images taken by the author, 2015. Drawing of the underground connecting system beneath the abbey (Lower). The vertical connections that join these tunnels with the surface have been drawn in red. Technical gadgets and platforms designed by the duke to connect the buildings to the estate’s underground. Drawing by the author, 2015.

On this special occasion, we had the opportunity to wander through the interior of these ceilings, where a part of the family’s history has been safeguarded. The duke decided to hide the room’s original structure by building a giant mask with which to hide its true luxury. The section was modified to make its essence invisible; skylights and beams have remained hidden behind the new structure ever since. When the small camouflaged door is opened a ladder slides down, showing its true nature. A tiny hatch allows access to the insides of this place; the view is overwhelming as we submerge our heads into it (A written map of the “Dukeries” and Worksop, with interesting drawings and illustrations of underground paths, holes, and shortcuts in the forest. The text compares these strategies in the landscape with the alterations made to the ceilings of the Abbey Chapel where part of the family history was guarded, in SISSONS, C (1896): The Chapel’s alterations. Beauties of Sherwood Forest, p. 102, Wentworth Ed.). This open incision in the ceiling reveals the presence of a hidden space (Figure 8). Never before had these images been unveiled. It was an odd place, illuminated and drained by the size of its elements, turned upside down as if the room had folded in on itself. Two superimposed structures from different times intersect into a single one, a strange and convex space without scale. With this hypothetical mass, the hidden side of a mask was cleverly placed to conceal an invisible concavity, a place in which concentric worlds overlap. The structure creaks to the rhythm of our steps, and the noise and vibration transports us to a weightless world, as if we were making an intimate journey whilst floating in space. When we reach the top, we raise our heads; the ordered repetition of elements, the space’s horizontal dimension and its scarce height, in our eyes, turn it into an almost infinite place.

Figure 8.

Titchfield Library, 1896. (left) The old Riding Hall was converted into a library and chapel by the 5th Duke of Portland (Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham, Nottingham). (center) Hatch into the false ceiling. In the images taken during the author’s visit in October 2015, the wooden beams have disappeared. (right) A new roof, carved with natural and divine images, hovers over our heads, molding space with a new shape.

Inside a building, there are infinite sceneries, permanent and variable, as well as visible and hidden. Our mission is to discover them and then recreate them in our projects. This place constitutes an entire landscape, a landscape inside another, a world of shapes that wait patiently to be discovered. All these thoughts, these real and imagined sensations, force us to think about the relationship we establish with architecture, prior to the mere distribution of functions and spaces. The idea of finding myself behind the scenes, in a place that belongs to its own privacy, represents a scenographic rather than an architectural space. The reason that led the duke to undertake such a large enterprise is unknown. Years of work and hundreds of thousands of pounds were invested in the construction of this landscape that not only reveal a fascinating personality but show ways of getting around without being seen, getting lost without looking for a destination, and going underground to find oneself.

Every evening, the duke would begin his ritual. He would leave his house and walk under the extensive park, only in dim light and always beginning at the same place, Plant Corridor, which is a kind of semi-buried linear garden covered with plants and flowers. A longer corridor was built parallel to this line, narrower and more abruptly carved, which connects the abbey to the Riding School. The map of underground lines seems to multiply as we go further on our underground walk. In tunnel number two, about 10 m wide and 500 m long, the house’s exteriors are linked with a second line, 2 km long, which connects the Riding School to the Northeast Country House, where the duke’s carriage would emerge to take him straight to Retford station (tunnel number 1). Unlike other lines designed for pedestrians, these two tunnels intertwined with each other, abiding to an interior dimension and trajectory that enabled the movement of a horse carriage. This tunnel, which is the longest, runs under the road we walked along this morning and leads to South Lodge, a gate at the limit of the estate, which facilitates a fast exit from the abbey in just 20 min.

The ground is full of other lines, small remnants, tunnels, as well as shortcuts and detours that connect and articulate the tunnels, weaving an extensive network under the estate’s surface (Figure 9). A grotto tunnel, carved profusely into the stone, makes it possible to move under one of the roads that divides the park, while another emerges with a ramp below the Riding School. There are many which preserve the narrow gauge, and others of rectangular section and slender proportions, decorated with paintings and antlers, lead to subterranean spaces that are breathtaking due to their size and beauty. Dozens of passages dispersed throughout the territory create a kind of rhizome that expands underground; some have already been swallowed up and closed off by nature itself, while others are conserved in a difficultly reversed state, patiently awaiting a new future.

Figure 9.

(a) Underground Welbeck Estate, 2015. (Unpublished cartography developed by the author, 2015). 2. Future School of Architecture (old stables)_ 3. Editorial Funds (former Riding School)_ (b) Underground Welbeck Estate, 2015. In diagonal, tunnel n° 1 linking to the South Lodge. Vertically tunnel n° 2 connects the Abbey to the previous tunnel. (Unpublished cartography developed by the author, 2015). 13. Rose Corridor_ 14. Sunken Garden_ 16. Underground Ballroom_ 20. Oxford Wing.

Robert Mayo suggests showing us one last spot, one of the duke’s last inventions, perhaps the most ostentatious, another underground room, completely diaphanous and of gigantic proportions, illuminated by forty large skylights. It is surprising how much light can flood the space through its thick ceiling. The acoustics are amazing, although the sound is amplified when speaking in a low voice, creating an echoing around the room. This space helps us understand that perception does not happen either in the body, or in space, but in the established relation between them. It is the ballroom, the largest in Europe at the time, the only underground one, equipped with some technical devices, that we will discover during our visit. The ground seems like it is lit with sun rays; back in the day, the white and empty walls were ornamented with part of their painting collection. On one side, an enormous half-opened door gives us a glimpse of the gardens and connects the room to the park’s surface with a kind of elevating platform hidden between its walls. At the other end, another door of similar dimensions connects this space to the underground network, providing access from the lineal underground garden.

The duke was known for offering his guests the latest in amenities and technical advancements. Undoubtedly, this was the room where most of the guests came together. They say that, when arriving at a large party at Welbeck Abbey, guests were transported to the Ballroom while still in their carriages, by a hydraulic lift and a gently tilted tunnel, leading them directly to the ballroom (Figure 10). It was such a studied scenery, whereby guests were witness to a magical moment, entering a landscaped corridor from the park to gently descend down to the chamber. There, the duke waited for them and, after receiving them, ordered the carriages to disappear.

Figure 10.

Underground ballroom. The huge room, covering approximately 1200 square meters, was originally intended to fit the new chapel. The ceiling was built with large metal beams. The photographs, taken by the author in October 2015, show its current condition.

The greatest value of this space is its ability to trick others in what cannot be seen. This spatial mechanism emitted a gravitational force so great that it left all the guests absolutely flabbergasted. A handwritten letter found in the archives narrates: “A servant precedes us, showing us the way to the Ballroom. We follow him through a dimly lit corridor that looks more like a theater’s elevator than a stately house. We entered here from the park through a kind of covered lodge, in which several carts await the entrance ritual. The sounds of the dance filtered through, like a joyful noise in the street; the echo of a wave of applause resounded from deep within the earth, and as if fleeing from them the duke appeared, hurrying up that ramp; we descended from our carriage and without knowing very well how it happened, he disappeared before our very eyes.” (The text transcribes the letter that, in the first person, is narrated by one of those attending the Ballroom, with expressions as beautiful as the sounds of the dance filtered through, like a joyful noise in the street, or without knowing very well how it happened, he disappeared before our very eyes. The text shows the greatness of this space, a territory of real personal and architectural experimentation, in WHITE, R (1922): The Underground Library. Worksop, the Dukery and Sherwood forest, p. 77, Duke University Librarys Ed.). Without a doubt, the duke turned this theatricality into his signature and way of life. His home became an extension of his behavior, and acted as a stage, as big and complex as that of an opera, in which a certain subjectivity unfolds, an incredible space, unfolded and parallel; A territory of real architectural experimentation.

This architecture, this extraordinary space in which the visible and the concealed seem to get confused, shares some of its strategies with those of a theatrical stage. A double bottom filled with tensions and articulations, a double world offered as a game to which one feels invited to (Figure 11). This territory ceases to be merely a place in which to install privacy, to become a space for its own representation, with which to introduce itself to the world to foment its myth. Even to this day, it impresses when visited. Robert activates some of the mechanisms right before us with which we can recreate its function in our imagination. Levers, pulleys, and platforms located all throughout the duke’s buildings offered ingenious encounters between the underground tunnels and the spaces built up on the surface.

Figure 11.

Welbeck Tunnel run, 2015. Duration: 4,03′. Shot in the summer of 2015, the camera records an anonymous person’s run through tunnel n° 1. The film’s main interest is the action of exploring this space, the emotion and pleasure of getting lost inside the tunnels.

3. Conclusions

The main author of this story, the reader, and the secondary characters intertwine in order to highlight the boundaries between fiction and reality. It is the obsessive work of a person suffering from a skin disease, trying to live without being seen, moving in the interstices of his estate, in a double world invented for his own life. The story’s pulse coexists with the vertigo raised by the 5th Duke, who discovered and understood the working of his own cognitive process, which gave him the power and the possibility of transforming the laws of physics that govern our idea of movement, time, and space. At Welbeck Estate, these laws seem to be suspended and reveal the ineffectiveness of what sustains them. The main character’s movement is multiplied in a whole series of heterodox actions that modify the notions of space and time. Everything that happens in this narrative creates a kind of domestic scenery that conspires against the world as we know it, and is shown as an inaccessible, untouchable, and imperceptible space [10].

The renovations by the 5th Duke of Portland at Welbeck Estate can be considered, technically and conceptually, pioneers in the evolution of 19th century country houses. Welbeck is the best example of Chase and Levenson’s theory of theatricalized domestic spaces, of this kind of spectacle of intimacy, of a domestic architecture conceived as a scenographic mechanism that allows the public exposure of its owner’s life [11]. The duke claims the thickness of earth, the underground as a private place, a burrow, a hole in which to safeguard his own privacy with zeal. A new space associated with home, a concealed and buried super structure, has become a model of architectural landscape. The corridor and cell network have reached, with the Duke’s projects, the largest domestic dimensions known to date, turning the ground of his estate into a space of voluntary occupation, a labyrinth of connections and territorial relations that extends endlessly under his estate.

In a way, this paper raises the Welbeck Estate model as a phenomenological framework in the way architecture is made, by examining how it relates building with site and situation; body to architectural space; and body and architecture at the same time. In short, a scientific investigation is used to delve into the haptic sensitivity of the architect to articulate spaces and forms [12]. The intangible space appears and, with it, the body. The research, thus, opens up a field of study on architectural practice and the philosophical engagement of architecture.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.I.F.N. and T.G.G.; methodology, M.I.F.N. and T.G.G.; software, M.I.F.N. and T.G.G.; validation, M.I.F.N. and T.G.G.; formal analysis, M.I.F.N. and T.G.G.; investigation, M.I.F.N. and T.G.G.; resources, M.I.F.N. and T.G.G.; data curation, M.I.F.N. and T.G.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.I.F.N. and T.G.G.; writing—review and editing, M.I.F.N. and T.G.G.; visualization, M.I.F.N. and T.G.G.; supervisión, M.I.F.N. and T.G.G.; project administration, M.I.F.N. and T.G.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is done by the authors without funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I wish to acknowledge the support provided by all the staff at the University of Nottingham Library for their invaluable help, before and during our visit. It involved hard work, with moments charged with great emotional intensity and some interesting findings that would not have been possible without the help of: Kathryn Summerwill, archivist and systems. Manuscripts and Special Collections. The University of Nottingham. King’s Meadow Campus, Lenton Lane. I would like to offer my special thanks to Robert Mayo, Director of Development, Welbeck Estates Company LTD. All individuals included in this section have consented to the acknowledgement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adlam, D. Tunnel Vision: The Enigmatic 5th Duke of Portland; The Harley Gallery: Nottinghamshire, UK, 2013; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman-Keel, T. The Disappearing Duke: The Intriguing Tale of an Eccentric English Family—The Story of the Mysterious 5th Duke of Portland; Seek Publishing: London, UK, 2005; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Phenomenology of Perception; Éditions Gallimard: Paris, France; Routledge & Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1945; p. 83. [Google Scholar]

- Blainey, A. Fanny and Adelaide: The Lives of the Remarkable Kemble Sisters. Theatre J. 2002, 54, 334–335. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture; Rizzoli International Publications: Tucson, AZ, USA, 1980; p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, T. Hidden Space Cartographies. Laboratory for Architectural Experiments. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, University of Seville, Seville, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pallasmaa, J. The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996; p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- Koolhaas, R. Corridor, Elements of Architecture; La Biennale di Venezia: Venice, Italy, 2014; p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury, D. Welbeck Abbey: Treasures; Ed. Bradbury: Nottingham, UK, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Trigg, D. Thing, The_A Phenomenology of Horror; John Hunt Publishing: Winchester, UK, 2014; p. 88. [Google Scholar]

- Chase, K. The Spectacle of Intimacy: A Public Life for the Victorian Family; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2000; p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- Holl, S. Questions of Perception: Phenomenology of Architecture; William K Stout Pub.: London, UK, 2007; p. 102. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).