1. Introduction

Women’s reproductive health is a fundamental determinant of overall quality of life and is closely related to the complex physiology of the female reproductive system, which regulates the development of secondary sex characteristics, supports gametogenesis, secretion of sex hormones and embryonic development, while remaining highly susceptible to a wide spectrum of internal and external influences [

1]. Disturbances in its functioning lead to serious reproductive complications such as precocious puberty, irregular menstrual cycles, premature ovarian insufficiency, endometriosis, uterine fibroids or pregnancy-related complications [

2].

Plastic materials have become an essential part of everyday life, with applications spanning the food industry, healthcare, electronics, and transportation, among others. However, their degradation products, in the form of microplastics (MPs) and nanoplastics (NPs), are now detected in virtually all environmental compartments, including plants, animals, and humans [

3]. Many everyday products also contain biologically active contaminants that may pose a growing threat to the female reproductive system [

4].

Infertility—defined as the inability to conceive after 12 months of regular, unprotected intercourse—affects an estimated 50 to 80 million women worldwide [

5]. Among its main causes are uterine and ovarian dysfunctions, which may be triggered or exacerbated by exposure to MPs [

6]. Consequently, the potential impact of MPs and NPs on women’s fertility has become the subject of increasing scientific awareness. Evidence from animal models indicates that these particles can induce granulosa cell apoptosis, diminishes ovarian reserve, and compromise oocyte quality, thereby decreasing the likelihood of successful pregnancy [

7]. These reproductive effects are linked to elevated production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), activation of inflammatory pathways, and disruption of hormonal regulation [

8].

Available evidence from human studies demonstrates a significant association between chronic exposure to MPs and NPs and reduced fertility [

9]. These particles can accumulate in reproductive organs, damage cellular structures through various intracellular pathways, and disrupt the cell cycle due to their toxic effects [

10]. Their ability to penetrate the placental barrier leads to transgenerational toxicity and interferes with normal embryonic development [

11]. Furthermore, alterations in gene expression within trophoblast cells may impair both maternal and fetal immune function, increase the risk of spontaneous abortion, and compromise overall maternal health [

12].

Despite growing scientific interest in MPs and NPs, many critical questions remain unresolved—particularly regarding their precise toxicity mechanisms, patterns of accumulation in human tissues, and long-term effects on the female reproductive system. Moreover, the absence of standardized analytical protocols for reliable detection and quantification of MPs and NPs in biological samples hinders comparability across studies.

This review provides a comprehensive overview of current knowledge on the effects of MPs and NPs on the female reproductive system, integrating data on biodistribution, penetration mechanisms, and potential exposure pathways that are often less thoroughly addressed in previous reviews. In contrast to many publications that primarily focus on toxicological outcomes, this paper also offers a critical evaluation of current analytical challenges and recommends standardized protocols to minimize contamination in clinical sample analyses, as well as links between oxidative stress, inflammation, endocrine disruption, and the translational gap between animal and human studies. This integrative approach allows for a more complete understanding of the complexity of the issue and identifies key knowledge gaps to guide future research.

2. Environmental Distribution of Micro- and Nanoplastics

Plastic particles pose a serious environmental hazard due to their ability to rapidly infiltrate diverse environmental compartments. They enter marine and freshwater ecosystems, soils, and the atmosphere, where they disperse and accumulate over time. Once present in water and soil, these particles can migrate through the food chain, contaminating plants, animals, and ultimately the human body. MPs may also occur in the atmosphere as aerosolized droplets or as micro- and nanoscale fragments originating from synthetic textile fibers, wear and tear from synthetic rubber tires, urban dust, fragments from clothing, household appliances, construction materials, waste incineration, landfills, industrial emissions, road traffic, and the application of sewage sludge as agricultural fertilizer [

13]. Their aerial distribution is influenced primarily by meteorological factors—most notably wind speed and direction—and atmospheric transport of MPs occurs more rapidly than their movement in soil or aquatic environments [

14].

The presence of MPs has been documented in a wide variety of consumer products, including water (tap water and bottled water), personal care products (soaps, shampoos, deodorants, moisturizers, shaving creams, sunscreens, and facial masks—along with decorative cosmetics like lipsticks and eye shadows [

15]), household products (furniture, textiles, electronic equipment), and food (plant-derived products [

16], seafood, fish, shellfish [

17], honey, spices, vegetables and fruits [

18]). The polymer composition of MPs is highly heterogeneous. The most frequently detected polymers include polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polyamide (PA), polypropylene (PP), polystyrene (PS), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyethylene (PE), low-density polyethylene (LDPE), polyurethane (PU), and polycarbonate (PC) [

19]. Each polymer type is associated with distinct commercial applications; for example, PET is commonly used for beverage bottles, food packaging, and textiles, PP for bottle caps, carpets, and automotive components, and PC for products ranging from security windows to compact discs (CDs) [

20].

3. Exposure and Distribution Pathways of Plastic Particles in the Human Body

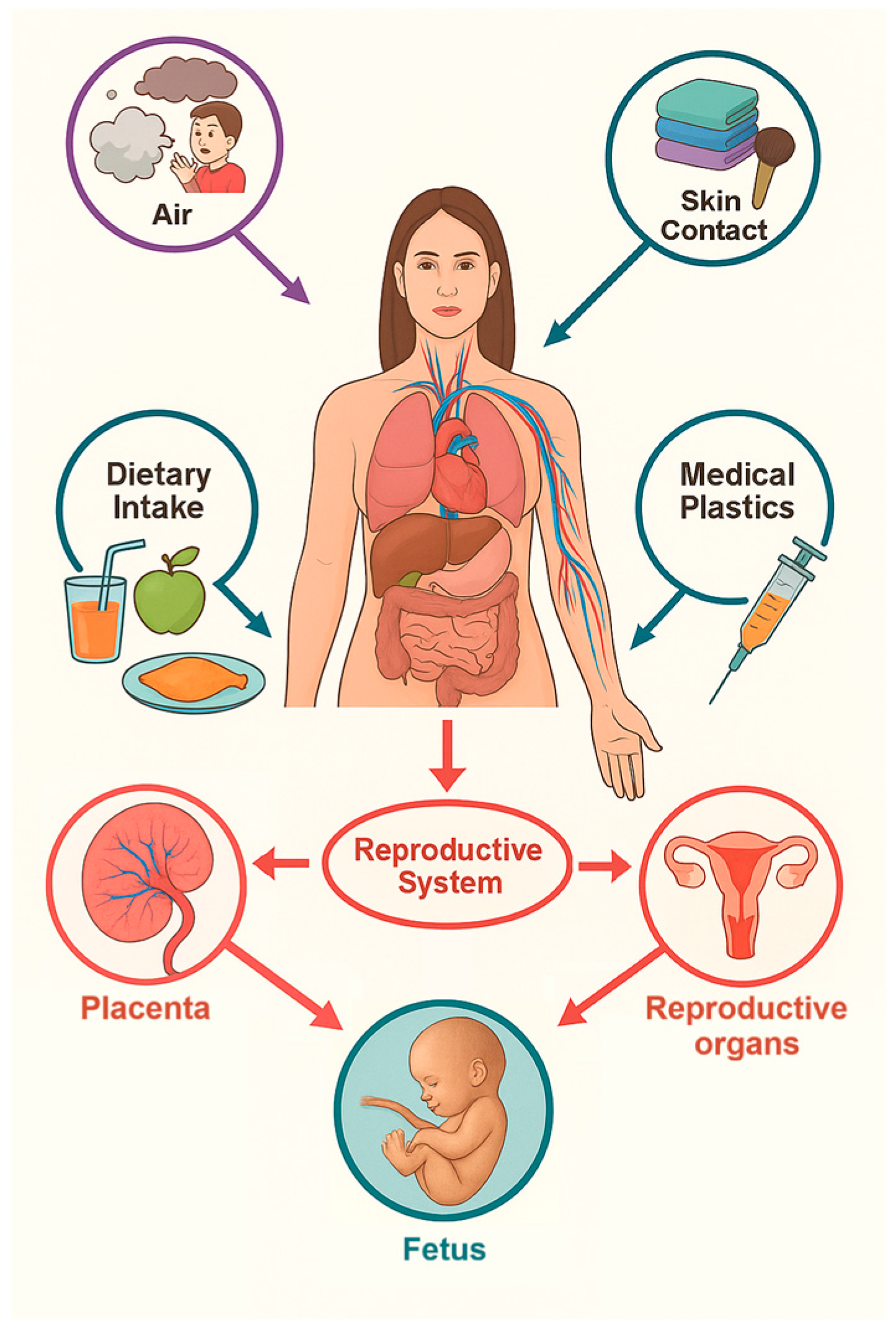

MPs and NPs can enter the human body through four primary exposure routes: oral ingestion, inhalation, transdermal absorption, and iatrogenic introduction (

Figure 1). These pathways determine the extent and pattern of particle distribution within the body and influence subsequent toxicological effects [

14].

These exposure pathways may pose significant health risks [

22] while the biodistribution and persistence of plastic particles within the body are largely influenced by their morphometric characteristics [

15]. The ability of MPs particles to penetrate biological barriers is strongly dependent on their size. Particles exceeding 150 μm generally fail to enter the systemic circulation, whereas those smaller than this threshold can traverse the intestinal epithelium and subsequently access the lymphatic and circulatory systems. MPs measuring approximately 20 μm have the ability to infiltrate parenchymal organs, while the smallest particles (0.1–10 μm) are capable of penetrating cellular membranes and crossing both the blood–brain barrier and the placental barrier [

23]. In addition to the particles themselves, the degradation of plastic materials can also lead to the leaching of chemical additives, such as phthalates and bisphenol A (BPA), which are known endocrine-disrupting compounds and pose potential health risks [

21].

3.1. Oral Exposure

In addition to dietary sources discussed in

Section 2, drinking water—whether from public tap systems or bottled sources—represents a significant pathway of microplastic intake. In a study by Kosuth et al., analysis of 159 public tap water samples revealed the presence of MPs in up to 81% of tested specimens [

24]. Furthermore, plastic food packaging materials have been identified as an additional source of MPs, particularly when subjected to elevated temperatures, which promotes particle release. This phenomenon has been documented across a variety of products, including tea bags, plastic teapots, and infant feeding bottles [

25].

3.2. Respiratory Exposure

Systematic surveys documenting the presence of MPs in atmospheric samples from diverse geographic regions confirm their ubiquitous distribution and highlight the potential health hazards associated with airborne particle inhalation The deposition of MPs within the respiratory tract is strongly size-dependent, with mucociliary clearance efficiency declining markedly for particles smaller than 5 μm in diameter [

26]. The pulmonary alveolar region—characterized by an extensive surface area of approximately 150 m

2 and an exceptionally thin alveolar–capillary barrier (<1 μm)—offers suitable conditions for the penetration of nanoparticles into the capillary bloodstream, enabling their systemic distribution [

27]. Consequently, the type I pneumocytes serve as the principal target site for inhaled nanoparticles, whose biological reactivity is closely determined by their physicochemical properties [

28]. Of particular concern is the evidence that infants and young children inhale microplastics at levels 3- to 50-fold higher than adults, underscoring the critical importance of environmental safety during critical stages of human development [

29].

3.3. Dermal Exposure

The transdermal penetration of plastic particles is predominantly determined by their size and chemical characteristics. Particles smaller than 4 nm can easily penetrate intact skin. Those ranging from 4 to 20 nm are capable of partial penetration through both healthy and damaged skin, whereas particles between 21 and 45 nm can only penetrate compromised skin. Plastic particles exceeding 45 nm do not breach the epidermal barrier but instead accumulate within the stratum corneum [

14]. Experimental findings by Gopinath et al. demonstrated that nanoparticles released from cosmetic products can induce cytotoxic effects in keratinocytes by triggering oxidative stress (OS), thereby inhibiting cell proliferation [

30].

3.4. Iatrogenic Exposure

Plastic materials play a pivotal role in modern medical applications thanks to their unique combination of desirable properties, including low weight, high chemical resistance, and the capacity for sterilization. Common medical-grade plastic products include intravascular catheters, stents, prostheses, and a variety of implants that are indispensable for patient diagnosis and treatment. Additionally, plastics are extensively used in the production of infusion containers, tubing, syringes, and needles. The selection of these materials is driven by their durability, lightness, and ability to meet strict medical quality and safety standards [

31]. Although direct evidence for the release of MPs and NPs from medical plastics into the human body is lacking, experimental and observational data support the hypothesis that such materials can undergo degradation, leading to particle release. This process may be triggered by exposure to chemical agents, temperature fluctuations, and other physicochemical factors [

21].

4. Systemic Distribution and Biokinetics of Micro- and Nanoplastics in the Human Body

Once MPs enter the human body, they may initially accumulate within the digestive tract, yet the porous architecture of the intestinal epithelium facilitates their translocation into the systemic circulation—a phenomenon confirmed by analyses of colectomy specimens. The lymphatic system plays an essential role in the distribution of MPs, similar to the transport of immune cells [

32]. MPs have been detected in a wide range of human biological tissues (e.g., colon, spleen, liver) and body fluids (e.g., blood, thrombi, sputum, breast milk), as well as in stool samples [

18]. Notably, Zhao et al. detected six distinct MP types in ejaculate and testicular tissue using laser direct infrared (LDIR) spectroscopy [

33], while Zhu et al. documented their presence in human placentas, umbilical cord blood, and meconium [

34].

The distribution of MPs to different tissues is mediated primarily via the circulatory system. At the cellular level, NPs are internalized through multiple uptake mechanisms, including phagocytosis, pinocytosis, macropinocytosis, caveolin- and clathrin-mediated endocytosis, as well as dynamin-independent endocytosis pathways [

35,

36]. Smaller NPs may permeate cell membranes by passive diffusion, provided their dimensions permit passage through membrane pores [

37]. Once internalized, NPs accumulate in the cytoplasm, where phagosomes containing these particles can fuse with endosomes to form hybrid vesicular structures. These subsequently traffic the NPs to lysosomes, where they may induce structural and functional cellular damage [

38].

Recent evidence suggests that MPs and NPs may exploit endogenous extracellular vesicle (EV) pathways to facilitate their systemic dissemination and cellular communication. EVs, including exosomes (40–120 nm) and microvesicles (50–1000 nm), are lipid bilayer vesicles released by virtually all cell types and are key mediators of intercellular signaling through the transport of proteins, lipids, and regulatory RNAs. Calzoni et al. comprehensively reviewed the emerging evidence linking MPs with EV biology, emphasizing that plastic particles can alter EV biogenesis, release, and molecular cargo, thereby influencing cell–cell communication and potentially exacerbating inflammation, oxidative stress, and metabolic dysregulation [

39]. Experimental data support this interaction: in a porcine model, serum-derived EVs were shown to carry PET particles, as demonstrated by PET-specific fluorescence and time-resolved spectroscopy. Simultaneously, the miRNA cargo of circulating EVs was significantly remodeled, affecting pathways associated with insulin resistance, carcinogenesis, and cardiovascular disease. Similar findings were reported in murine models, where exposure to PS-MPs induced ROS-dependent EV release and pro-fibrotic signaling in renal tissue. Collectively, these observations support the concept that EVs may serve as biological shuttles for MPs/NPs, enabling their translocation to distal organs and amplifying their toxicological impact across cellular systems [

40].

The biological consequences of MP and NP uptake are substantial. In vivo experimental studies demonstrate systemic exposure associated with adverse health outcomes, including immunomodulation, apoptosis, OS, disruption of neurotransmission, metabolic dysregulation, and sustained inflammatory activation [

41]. Furthermore, chemical additives such as plasticizers, antioxidants, flame retardants and pigments added during the manufacture of plastic materials may be released during their use or degradation, subsequently entering the human body and bioaccumulating within tissues where they provoke pathological changes. Many of these compounds act as endocrine-disrupting chemicals, interfering with reproductive physiology through estrogenic and/or (anti-) androgenic mechanisms [

42]. In addition, MPs possess a strong capacity to adsorb environmental contaminants, including metals and organic chemicals. The extent and specificity of adsorption depend on intrinsic polymer characteristics such as surface area, diffusivity, and hydrophobicity [

43].

5. Analytical Methods for the Detection of Micro- and Nanoplastics in Biological Samples

The detection and quantification of MPs and NPs in biological samples presents significant methodological challenges, requiring highly accurate and reliable analytical techniques capable of identifying, characterizing, and quantifying these particles in tissues and body fluids [

44].

5.1. Spectroscopic Methods

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) is one of the most widely employed techniques, enabling the identification of polymeric composition based on characteristic absorption spectra. FTIR is particularly effective for particles larger than 20 μm, providing robust and reproducible polymer identification [

45]. Raman spectroscopy (RS), by contrast, is suitable for detecting smaller particles (≥1 μm) and offers detailed molecular characterization; however, its performance is limited by interference from sample fluorescence, which may compromise sensitivity [

46]. LDIR spectroscopy has recently emerged as a powerful high-resolution approach, enabling rapid and automated identification of MPs in complex biological samples [

47].

5.2. Microscopic Methods

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) provides high-resolution morphological characterization and precise size determination of MPs and NPs. When coupled with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), SEM also facilitates elemental composition analysis. Despite its advantages, this approach requires extensive sample preparation [

48,

49].

5.3. Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry Methods

Mass spectrometry-based approaches, including liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and pyrolysis–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (Py-GC-MS), enable both the quantification and identification of polymers following thermal degradation or chemical extraction. These methods are particularly advantageous for the detection and quantification of NPs, which often remain below the detection thresholds of spectroscopic methods [

50].

5.4. Comparative Evaluation of Analytical Methods

The detection of MPs and NPs in biological and environmental samples poses a major analytical challenge due to their wide variability in size, chemical composition, and the complexity of sample matrices. Each of the abovementioned techniques offers unique advantages and inherent limitations in terms of sensitivity, specificity, reproducibility, and practicality. FTIR spectroscopy remains one of the most widely applied methods owing to its versatility, simplicity, and relatively short analysis time. It provides excellent chemical specificity for polymer identification and good sensitivity for particles larger than 20 μm. However, its performance declines for NPs, and the complex background of biological matrices often necessitates meticulous sample preparation to reduce spectral interference.

Raman spectroscopy complements FTIR by achieving higher spatial resolution, allowing detection of particles down to approximately 1 μm and enabling the identification of both polar and nonpolar chemical bonds. Nevertheless, fluorescence sensitivity and the requirement for prolonged acquisition times can reduce its practicality for high-throughput analyses of biological samples.

LDIR spectroscopy represents a promising advancement in the field, offering automated, high-throughput, and reproducible polymer identification. Its ability to analyze thousands of particles within minutes makes it particularly valuable for environmental and biomonitoring studies. However, the high operational cost and limited accessibility of this technology currently restricts its broader application.

SEM/EDS provides unparalleled morphological detail and elemental composition data, making it indispensable for visualizing the structure and surface characteristics of MPs and NPs. Yet, the method requires extensive sample preparation, operates under vacuum conditions, and is less suited for soft or hydrated biological samples. Chromatographic methods such as Py-GC-MS, and in some cases LC-MS, allow quantitative and polymer-specific analysis of even nanosized particles through thermal or chemical decomposition. Although highly sensitive and reproducible, these methods are destructive and do not provide information on particle morphology or count [

49,

50].

In our perspective, the optimal analytical strategy should be multimodal, leveraging the synergistic strengths of complementary techniques according to specific research objectives. A direct comparison of currently available analytical methods highlights their distinct strengths and weaknesses in terms of sensitivity, specificity, reproducibility, and practical applicability. For large-scale, high-throughput screening, LDIR and FTIR spectroscopy represent the most promising combination, balancing automation and chemical specificity. For detailed characterization of biological samples, Raman spectroscopy and SEM/EDS remain indispensable due to their superior resolution and structural insight. Meanwhile, Py-GC-MS serves as the most accurate option for quantitative polymer identification, especially when particle integrity is not required.

Table 1 summarizes the comparative performance of these methods and outlines their respective advantages and limitations. Integrating multiple complementary approaches remains essential to achieve reliable, reproducible, and comprehensive detection of MPs and NPs in biological matrices. To address these limitations, the integration of complementary analytical approaches has become standard practice in current research (

Table 2). Such multi-method strategies improve accuracy, reduce false-positive rates, and enhance reproducibility in the detection of MPs and NPs in biological samples [

35,

36].

5.5. Standardized Protocol for Sample Preparation in Micro- and Nanoplastic Analysis

Accurate detection of MPs and NPs in both biological and non-biological samples requires the elimination of any risk of contamination with plastic particles during the entire sample preparation process. To address this challenge, a universally applicable “aplastic” protocol is recommended, providing a standardized, reproducible, and practically feasible approach designed to minimize plastic contamination from sampling through to processing [

54].

The fundamental principle of this protocol is the complete exclusion of plastic materials at every stage of sample handling. All instruments used for collection and processing are made exclusively of metal, wood, or glass—for example, scalpels, scissors, tweezers, and clamps. Samples are collected into reusable, sterilizable glass containers equipped with glass or metal closures, ensuring maximal integrity and purity. Prior to use, all containers are thoroughly sterilized, typically by autoclaving [

55].

Equally stringent measures apply to personal protective equipment and the working environment. Gloves are made of natural fibers, most commonly cotton. Surfaces that may come into contact with the sample are covered with sterile cotton cloths or towels. During manipulation, air circulation is minimized by switching off ventilation and air-conditioning systems to reduce the risk of airborne MP contamination.

This aplastic approach is flexibly adaptable to diverse sample types—including skin, placenta, blood, saliva, and other biological tissues—depending on the requirements of the analysis. It can also be applied to environmental matrices such as soil, water, and sediments. The protocol is strongly recommended for all analytical techniques targeting MPs and NPs, as it substantially reduces the likelihood of false-positive contamination and enhances the reliability and reproducibility of results. Adherence to this protocol is a critical prerequisite for generating high-quality, interpretable data in studies addressing plastic burdens in environmental and biological systems [

53].

Future progress in this field will depend critically on the standardization of sample preparation, the minimization of plastic contamination, and the harmonization of analytical protocols across laboratories. Establishing unified “aplastic” workflows and validation schemes will enhance reproducibility, facilitate cross-study comparability, and ultimately enable more precise assessment of human exposure and the reproductive toxicology of plastic particles.

6. Impact of Micro- and Nanoplastics on Women’s Reproductive Health

Experimental studies in animal models have demonstrated that exposure to MPs and NPs can adversely affect the female reproductive system through multiple pathophysiological mechanisms. These particles induce structural changes in tissues, resulting in functional dysregulation of both the uterus and the ovaries [

6,

51]. Disruption of the cellular architecture within the uterine endometrium markedly decreases the probability of successful embryo implantation, thereby elevating the risk of infertility and other reproductive disorders. Collectively, these pathological findings provide compelling evidence for a direct association between MP/NP exposure and an increased incidence of female reproductive complications [

56].

6.1. Ovarian Toxicity

The penetration of MPs and NPs into ovarian tissue and their subsequent impact on female reproductive health represent a relatively novel field of research, with underlying mechanisms only partially explained. Current knowledge of their biological effects comes mostly from studies in aquatic organisms, soil fauna, and more recently, mammalian models-rodents [

57].

In an experimental study by Hou et al., oral administration of 500 nm polystyrene nanoplastics (PS-NPs) at concentrations of 0.015, 0.15, and 1.5 mg/kg/day for 90 days in rats resulted in ovarian accumulation—specifically within the cytoplasm of granulosa cells—along with follicular depletion and reduced Anti-Müllerian hormone levels, indicating impaired ovarian function [

51]. A dose-dependent increase in malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration, coupled with a reduction in the activity of key antioxidant enzymes—glutathione peroxidase, catalase, and superoxide dismutase—suggested the induction of OS [

6]. Elevated levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-18 and IL-1β following exposure to 1.5 mg/kg/day of PS-NPs further confirmed activation of inflammatory pathways. NPs are believed to induce OS, thereby activating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade, which promotes granulosa cell apoptosis [

51]. Additional evidence from murine models demonstrates that exposure to 0.5 μm PS-MPs activates the NLRP3/Caspase-1 inflammasome signaling pathway via OS, ultimately leading to granulosa cell apoptosis and a reduction in follicle number [

6]. These findings indicate that oral exposure to PS-NPs can trigger both oxidative and inflammatory processes in ovarian tissue. Importantly, given the ability of NPs to traverse the follicular barrier, direct contact with oocytes is plausible, posing a significant threat to female fertility and underscoring the need for further research.

Beyond structural and functional impairment, MPs and NPs can act as carriers of hazardous chemical additives. Polyethylene MPs (PE-MPs), for example, can release BPA and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, compounds associated with elevated risks of ovarian, cervical, and endometrial malignancies [

58]. Similarly, organophosphate esters such as tri-o-cresyl phosphate—widely used as emollients—interfere with estrogen receptor α signaling in MCF-7 breast cancer cells, altering gene expression and promoting tumorigenesis, invasiveness, and metastasis through angiogenesis and enhanced nutrient uptake [

59].

Collectively, these findings indicate that MPs and NPs may impair female reproductive health not only through direct cytotoxic effects on ovarian and uterine tissues but also via endocrine disruption and alterations in microcirculatory homeostasis. Such mechanisms contribute to declining fertility, with evidence suggesting that women may be more vulnerable to these changes than men [

60].

6.2. Effect on Oocytes and Oogenesis

Oocytes are particularly vulnerable to MP/NP exposure. Biochemical analysis of rats exposed to MPs and NPs showed significant changes in OS levels in uterine and ovarian tissues. These changes were associated with histopathological abnormalities in the ovaries, including vacuolization of the ooplasm, granulosa, and interstitial cells, disruption of the corona radiata, and the formation of micronuclei within oocyte nuclei. Concomitantly, significant epithelial cell apoptosis and inflammatory responses in the endometrium were observed [

61].

Experimental findings further demonstrated that exposure to PS-MPs altered cytokine balance (increased IL-6 production) and reduced MDA levels in the ovaries of mice, leading to lower rate of first polar body extrusion and reduced oocyte survival. This reproductive toxicity is likely mediated by mitochondrial dysfunction (reflected by diminished mitochondrial membrane potential), reduced glutathione (GSH) levels, depletion of endoplasmic reticulum calcium stores, and elevated ROS production in oocytes, indicating that oxidative imbalance is the major driver of oocyte toxicity [

62].

Moreover, Cui et al. demonstrated in their study that exposure to MPs significantly reduced the quality of oocytes. This exposure manifested in maturation defects, including impaired extrusion of polar bodies, abnormalities in spindle and chromosome structure, as well as changes in cortical actin distribution. Metabolomic analysis revealed decreased levels of choline and creatine, which play essential roles in maintaining cellular structure and energy metabolism. These alterations subsequently led to mitochondrial dysfunction and increased oxidative stress, resulting in depletion of the intracellular antioxidant GSH, disruption of redox balance, DNA damage, and apoptosis. These findings underscore that MPs disrupt the redox homeostasis of oocytes, adversely affecting their maturation and posing a potential risk to female reproductive health [

61].

It has been proposed that the extent of MP/NP-induced toxicity to ovarian follicle oocytes may depend on the capacity of granulosa and cumulus oophorus cells to modulate particle activity, thereby mitigating harmful effects on the oocyte itself (

Figure 2). Two primary hypotheses have been formulated to explain potential entry routes of MPs/NPs into the oocyte: (1) direct penetration through the zona pellucida, the oocyte’s protective extracellular layer, and (2) transport via intercellular junctions between cumulus oophorus cells and the oocyte [

63].

In mammals, the zona pellucida—composed of glycoproteins secreted by the oocyte and adjacent follicular cells—forms an interlaced structural network that serves as both a mechanical and biochemical protective barrier. It prevents polyspermy following fertilization, thereby ensuring monospermic fertilization, while simultaneously facilitating bidirectional communication between the oocyte and surrounding cumulus oophorus cells [

64,

65]. This communication is mediated through transzonal projections (TZPs), specialized cellular extensions penetrating the zona pellucida. TZPs enable the transfer of essential metabolites such as pyruvate, as well as RNA and regulatory proteins including GDF9 and BMP15, which are indispensable for oocyte maturation and embryonic development [

66].

Interestingly, pores within the zona pellucida vary in size among species, ranging from 50–100 nm in pigs and rats [

67] to approximately 182 nm in cattle. Theoretically, particles smaller than 200 nm could penetrate this barrier [

68]. Notably, TZPs may provide an additional potential entry route, allowing MPs and NPs to bypass the otherwise protective function of the zona pellucida, thereby posing a significant risk to oocyte integrity and developmental competence.

6.3. Placental Transfer and Toxicity

The placenta plays a dual role during pregnancy: it facilitates the exchange of nutrients and gases between the mother and the fetus while simultaneously serving as a selective biological barrier against xenobiotics and pathogens [

69]. Increasing evidence indicates that MPs and NPs are capable of crossing the placental barrier via the maternal circulation [

53,

70]. Three principal mechanisms of transplacental transfer have been proposed: (1) passage through microscopic disruptions of the placental barrier caused by inflammatory processes [

71], (2) transcytosis via endocytosis, whereby MPs/NPs are engulfed and actively transported across trophoblastic cells [

72], and (3) immune cell-mediated transport [

32].

MPs measuring 5–10 μm have been detected in various compartments of the human placenta, including the maternal and fetal sides as well as the chorioamniotic membranes [

53]. Using transmission electron microscopy, Ragusa et al. documented MPs within pericytes and endothelial cells of chorionic villi, suggesting their potential to penetrate the fetal circulation and reach sensitive developing tissues. The accumulation of MPs in placental cells has been associated with enhanced production of ROS, apoptosis, and inflammatory activation, thereby increasing the risk of long-term metabolic disorders such as diabetes and obesity [

73].

Although studies on the effects of MPs/NPs in the human placenta remain scarce, emerging findings raise significant concern. In a murine model, Nie et al. reported that intravenous administration of PS-NPs (60 nm or 900 nm in size; 300 μg on gestational days 9 and 15) reduced both placental weight and neonatal birth weight. Moreover, 60 nm particles induced more severe cellular damage to placental and fetal tissues compared with larger 900 nm PS-NPs [

74]. Similarly, Hu et al. demonstrated that exposure to 10 μm PS-MPs during the peri-implantation phase increased embryonic resorption rates, reduced decidual natural killer (NK) cell numbers, elevated T-helper cell populations, and shifted macrophage polarization toward the immunosuppressive M2 phenotype. These findings highlight the potential for MPs to disrupt maternal–fetal immune balance [

75]. Although extrapolation of these findings from mouse models to humans is not straightforward, they provide new evidence and insights in assessing the potential reproductive toxicity of MP particles.

Additional mechanistic insights were provided by Aghaei et al., who reported severe metabolic dysregulation in placental tissue following exposure to 5 μm PS-MPs. Observed alterations included reductions in lysine and glucose concentrations—nutrients essential for fetal development—impairment of glycolysis and gluconeogenesis, disruption of the biotin cycle with consequent risks for developmental anomalies, and lysine accumulation due to impaired degradation [

76]. Further, PS-NPs were shown to affect cholesterol metabolism, alter sucrose and daidzein levels, disrupt complement and coagulation pathways, and modulate the expression of genes involved in inflammation and iron homeostasis, collectively posing a multifactorial threat to placental function and fetal growth [

77].

During pregnancy, the placenta ensures the exchange of gases and nutrients between the mother and the fetus, and the effectiveness of this process depends on adequate blood flow [

78]. Hemodynamic consequences have also been documented. Hu et al. found that exposure to 10 μm PS-MPs during early pregnancy reduced uterine arteriolar lumen diameter from the first trimester onward, while 100 nm PS-NPs interfered with coagulation pathways, compromising uteroplacental blood flow and fetal viability [

75]. Corroborating these findings, Aghaei et al. demonstrated that exposure to either 50 nm PS-NPs or 5 μm PS-MPs resulted in umbilical cord shortening, a condition directly associated with intrauterine growth restriction [

79].

Finally, in vitro studies provide further evidence of placental cytotoxicity. Shen et al. observed that PS-NPs induced G2/M cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and impaired proliferation in human extravillous trophoblast cells, confirming the deleterious potential of these particles within placental architecture [

10].

6.4. Impact on Embryonic Development

Research on the effects of MPs and NPs on mammalian and human embryogenesis remains in its infancy; however, accumulating evidence suggests that these particles may exert harmful effects on reproduction, embryo viability, and developmental health. Documented adverse outcomes include cytotoxic damage, inflammatory activation, endocrine disruption, and potential genotoxicity. Continued research is therefore critical to fully elucidate the risks and long-term consequences of plastic particle exposure during the earliest stages of life.

Park et al. examined the impact of repeated oral administration of PE-MPs in male and female mice at doses of 3, 7.5, 15, and 60 mg/kg/day for 90 days, with mating occurring between days 80 and 89 of exposure. While reproductive capacity was not directly impaired, offspring from parents exposed to the highest dose exhibited significantly reduced birth weights compared with controls [

52]. Consistent with these findings, Nie et al. demonstrated that intravenous injection of 300 μg of 900 nm PS-NPs on gestational days 9 and 15 significantly increased embryo resorption rates, indicating adverse effects on early fetal development [

74].

Additional experimental evidence links PS-MP exposure to decreased fertility, reduced embryo numbers, abnormal conception rates, and impaired embryonic growth. Female mice appear more susceptible to these effects than males, as reflected in lower survival rates and diminished embryonic development [

60]. Furthermore, MPs have been shown to induce sex-specific alterations in offspring, including abnormalities in sex ratios, differential body weight outcomes, and metabolic disturbances in lipid and amino acid pathways, which may extend to subsequent generations [

52].

At the cellular level, MPs and NPs disrupt embryogenesis primarily through OS-induced apoptosis, with excessive ROS production, which reduces GSH availability and compromises normal embryo development [

80]. Emerging studies also highlight the neurodevelopmental consequences of prenatal MP exposure. In murine models, maternal exposure during pregnancy and early development has been associated with structural brain abnormalities, metabolic dysregulation, and cognitive impairment in offspring [

81]. NPs are capable of crossing the fetal blood–brain barrier, localizing in regions such as the thalamus, where they interfere with neuronal differentiation through suppression of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) synthesis [

82].

Collectively, these findings underscore the potential of MPs and NPs to impair embryonic and neurodevelopment, induce sex-specific outcomes, and possibly exert transgenerational effects. Longitudinal studies are urgently needed to clarify the extent of these risks in humans and to establish their relevance for reproductive and developmental health.

6.5. Limitations of Existing Studies

Findings from experimental studies using animal models—predominantly rodents—and in vitro systems often serve as the basis for understanding the effects of MPs and NPs on the female reproductive system. However, it is essential to critically consider the differences between these models and human biological complexity, which may substantially limit their direct applicability.

In rodents, studies have shown that exposure to PS-MPs induces granulosa cell apoptosis, reduces follicle numbers, and activates inflammatory pathways through oxidative stress [

6]. Nevertheless, rodents differ from humans in metabolism, reproductive cycle length, and hormonal regulation, which complicates the extrapolation of these findings. In vitro models using human placental cells have demonstrated the ability of PS-NPs to induce apoptosis and cell cycle arrest [

10]; however, these systems fail to fully reflect the interactions among diverse cell populations and the systemic immune environment.

Another limitation lies in the experimental doses applied in animal and cell-based studies, which often far exceed realistic human exposure levels. For instance, animals are typically exposed to concentrations in the mg/kg/day range, whereas actual human exposure is estimated to be in the microgram range per day through ingestion and inhalation. This discrepancy underscores the need to characterize dose–response relationships and chronic effects at environmentally relevant exposure levels.

Despite these limitations, pilot clinical studies have confirmed the presence of microplastics in human placental tissue, umbilical cord blood, and meconium [

34,

53], suggesting that these particles can penetrate the maternofetal environment and potentially undergo transplacental transfer. However, the long-term health implications remain unclear and warrant detailed longitudinal clinical investigations.

7. Conclusions

MPs and NPs represent an emerging environmental threat with profound implications for female reproductive health. Experimental evidence and preliminary clinical observations converge to suggest that these particles impair oocyte quality, deplete ovarian reserve, trigger inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, and endocrine disruption, and possess the capacity to traverse the placental barrier, thereby jeopardizing fetal development. In addition, MPs and NPs appear to disrupt the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis, resulting in hormonal imbalances and impaired gonadal growth. Detection of plastic particles in human placental tissue, umbilical cord blood, and neonatal meconium further confirms exposure beginning at the earliest stages of embryonic development.

Of particular concern are indications of potential transgenerational toxicity, raising the possibility that reproductive health may be compromised not only in directly exposed individuals but also in subsequent generations. Despite these alarming findings, longitudinal clinical studies remain scarce, and the precise molecular mechanisms underlying MP- and NP-induced reproductive toxicity are yet to be fully explained.

With the growing body of evidence confirming the presence of microplastics in human biological samples and their potential impact on female fertility, it has become essential to define clear research priorities for assessing exposure and elucidating toxicological mechanisms. Future investigations should emphasize interdisciplinary, longitudinal studies focusing on low-dose and chronic effects to validate the biological relevance of experimental findings in clinical populations, therefore the research priorities should include: (i) the optimization and standardization of analytical methodologies to ensure reliable detection and quantification of MPs and NPs in biological samples, including the adoption of unified aplastic protocols to minimize contamination; (ii) the implementation of advanced experimental models, such as organoids and organ-on-a-chip systems, that recapitulate the physiological processes of human reproductive tissues—including trophoblastic, granulosa, and stromal cell interactions—to better elucidate mechanistic pathways; (iii) the design of studies employing environmentally relevant exposure doses with long-term monitoring to assess chronic and cumulative effects on reproductive function; and (iv) the development of longitudinal epidemiological cohorts integrating validated exposure biomarkers with clinical reproductive outcomes such as fertility, spontaneous abortion, and pregnancy complications. Achieving these objectives will require close interdisciplinary collaboration among toxicologists, clinicians, analytical chemists, and epidemiologists to develop safer alternative materials and effective preventive strategies aimed at safeguarding female fertility, improving reproductive health, and protecting the well-being of future generations.

Beyond scientific priorities, it is equally important to develop effective mitigation strategies. These may include strengthening environmental regulations governing the production and release of plastic particles, supporting the development and dissemination of biodegradable materials, and implementing plastic-conscious manufacturing technologies. Policy decisions at both national and international levels should be grounded in robust scientific evidence and reflect the urgent need to protect the reproductive health of women and the broader population. Public health can be significantly affected not only by direct exposure to microplastics but also by secondary consequences arising from food chain and environmental contamination.

Achieving these objectives will require close interdisciplinary collaboration among toxicologists, clinicians, analytical chemists, and epidemiologists to develop safer alternative materials and effective preventive strategies aimed at safeguarding female fertility, improving reproductive health, and protecting the well-being of future generations. Given the complexity and magnitude of this challenge, cooperation between researchers, policymakers, and the public is crucial to promote awareness, implement prevention, and ensure sustainable improvement in reproductive health and overall quality of life.

In this review, we provide a comprehensive synthesis of interdisciplinary knowledge on MPs and NPs and their potential impact on female fertility, emphasizing the importance of precise and standardized approaches to analytics and exposure assessment. Our work also identifies critical gaps in the available clinical evidence and highlights the need for more in-depth longitudinal studies to better evaluate long-term risks and mechanisms of toxicity. We underscore the importance of continued interdisciplinary collaboration in developing safer materials that could minimize the adverse effects of environmental contaminants on women’s reproductive health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.R. and L.G.; validation, M.K. and Š.P.; formal analysis, V.R. and O.E.H.S.; investigation, V.R., O.E.H.S. and L.G.; writing—original draft preparation, V.R. and L.G.; writing—review and editing, R.S.; visualization, R.S.; supervision, M.K. and Š.P.; funding acquisition, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used OpenAI’s ChatGPT (GPT-5, 2025) with image generation capabilities for the creation of schematic figures. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Balali, H.; Morabbi, A.; Karimian, M. Concerning Influences of Micro/Nano Plastics on Female Reproductive Health: Focusing on Cellular and Molecular Pathways from Animal Models to Human Studies. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2024, 22, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.N.; Moyle-Heyrman, G.; Kim, J.J.; Burdette, J.E. Microphysiologic Systems in Female Reproductive Biology. Exp. Biol. Med. 2017, 242, 1690–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, M.; Ihsanullah, I.; Tariq Khan, M.; Baig, N. Nanomaterials-Based Adsorbents for Remediation of Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Aqueous Media: A Review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 305, 122453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.B.P.; Carreiró, F.; Ramos, F.; Sanches-Silva, A. The Role of Endocrine Disruptors in Female Infertility. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 7069–7088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestris, E.; de Pergola, G.; Rosania, R.; Loverro, G. Obesity as Disruptor of the Female Fertility. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2018, 16, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, J.; Lei, Z.; Cui, L.; Hou, Y.; Yang, L.; An, R.; Wang, Q.; Li, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L. Polystyrene Microplastics Lead to Pyroptosis and Apoptosis of Ovarian Granulosa Cells via NLRP3/Caspase-1 Signaling Pathway in Rats. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 212, 112012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afreen, V.; Hashmi, K.; Nasir, R.; Saleem, A.; Khan, M.I.; Akhtar, M.F. Adverse Health Effects and Mechanisms of Microplastics on Female Reproductive System: A Descriptive Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 76283–76296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Zhou, C.; Xu, W.; Huang, Y.; Wang, W.; Ma, Z.; Huang, J.; Li, J.; Hu, L.; Xue, Y.; et al. The Ovarian-Related Effects of Polystyrene Nanoplastics on Human Ovarian Granulosa Cells and Female Mice. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 257, 114941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, I.; Khan, S.; Kushwaha, S. Developmental and Reproductive Toxic Effects of Exposure to Microplastics: A Review of Associated Signaling Pathways. Front. Toxicol. 2022, 4, 901798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, F.; Li, D.; Guo, J.; Chen, J. Mechanistic Toxicity Assessment of Differently Sized and Charged Polystyrene Nanoparticles Based on Human Placental Cells. Water Res. 2022, 223, 118960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurub, R.E.; Cariaco, Y.; Wade, M.G.; Bainbridge, S.A. Microplastics Exposure: Implications for Human Fertility, Pregnancy and Child Health. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1330396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Liu, Z.; Hu, R.; Huang, Y.; Li, F.; Ma, W.; Wu, X.; Dong, H.; Song, K.; Xu, X.; et al. Toxicity of Microplastics and Nanoplastics: Invisible Killers of Female Fertility and Offspring Health. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1254886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prata, J.C. Airborne Microplastics: Consequences to Human Health? Environ. Pollut. 2018, 234, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-D.; Huang, P.-H.; Chen, Y.-W.; Hsieh, C.-W.; Tain, Y.-L.; Lee, B.-H.; Hou, C.-Y.; Shih, M.-K. Sources, Degradation, Ingestion and Effects of Microplastics on Humans: A Review. Toxics 2023, 11, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çıtar Dazıroğlu, M.E.; Bilici, S. The Hidden Threat to Food Safety and Human Health: Microplastics. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 21913–21935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhou, Q.; Yin, N.; Tu, C.; Luo, Y. Uptake and Accumulation of Microplastics in an Edible Plant. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2019, 64, 928–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Love, D.C.; Rochman, C.M.; Neff, R.A. Microplastics in Seafood and the Implications for Human Health. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2018, 5, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wu, L.; Li, G.; Shi, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, L.; Chen, Y.; Yu, H.; Wang, K.; Xin, L.; et al. Atlas and Source of the Microplastics of Male Reproductive System in Human and Mice. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2024, 31, 25046–25058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelmans, A.A.; Redondo-Hasselerharm, P.E.; Nor, N.H.M.; de Ruijter, V.N.; Mintenig, S.M.; Kooi, M. Risk Assessment of Microplastic Particles. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2022, 7, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, Y.M.; Lehnert, T.; Linck, L.T.; Lehmann, A.; Rillig, M.C. Microplastic Shape, Polymer Type, and Concentration Affect Soil Properties and Plant Biomass. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 616645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, P.M.; Parvathi, V.D.; Yoghalakshmi, N.; Kumar, S.M.; Athulya, P.A.; Mukherjee, A.; Chandrasekaran, N. Plastic Particles in Medicine: A Systematic Review of Exposure and Effects to Human Health. Chemosphere 2022, 303, 135227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, J.C.; da Costa, J.P.; Lopes, I.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T. Environmental Exposure to Microplastics: An Overview on Possible Human Health Effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 702, 134455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, S.L.; Kelly, F.J. Plastic and Human Health: A Micro Issue? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 6634–6647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosuth, M.; Mason, S.A.; Wattenberg, E.V. Anthropogenic Contamination of Tap Water, Beer, and Sea Salt. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, L.M.; Xu, E.G.; Larsson, H.C.E.; Tahara, R.; Maisuria, V.B.; Tufenkji, N. Plastic Teabags Release Billions of Microparticles and Nanoparticles into Tea. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 12300–12310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasperi, J.; Wright, S.L.; Dris, R.; Collard, F.; Mandin, C.; Guerrouache, M.; Langlois, V.; Kelly, F.J.; Tassin, B. Microplastics in Air: Are We Breathing It In? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2018, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, R.; Weder, C.; Petri-Fink, A.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B. Emergence of Nanoplastic in the Environment and Possible Impact on Human Health. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 1748–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winiarska, E.; Jutel, M.; Zemelka-Wiacek, M. The Potential Impact of Nano- and Microplastics on Human Health: Understanding Human Health Risks. Environ. Res. 2024, 251, 118535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhu, F.; Zhou, S. Airborne Microplastics: A Review on the Occurrence, Migration and Risks to Humans. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2021, 107, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopinath, P.M.; Saranya, V.; Vijayakumar, S.; Mythili Meera, M.; Ruprekha, S.; Kunal, R.; Pranay, A.; Thomas, J.; Mukherjee, A.; Chandrasekaran, N. Assessment on Interactive Prospectives of Nanoplastics with Plasma Proteins and the Toxicological Impacts of Virgin, Coronated and Environmentally Released-Nanoplastics. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.K.; Sanyal, D.; Kumar, P.; Pulicharla, R.; Brar, S.K. Science-Society-Policy Interface for Microplastic and Nanoplastic: Environmental and Biomedical Aspects. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 290, 117985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enyoh, C.E.; Devi, A.; Kadono, H.; Wang, Q.; Rabin, M.H. The Plastic Within: Microplastics Invading Human Organs and Bodily Fluids Systems. Environments 2023, 10, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Zhu, L.; Weng, J.; Jin, Z.; Cao, Y.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, Z. Detection and Characterization of Microplastics in the Human Testis and Semen. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 877, 162713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Li, X.; Lin, W.; Zeng, D.; Yang, P.; Ni, W.; Chen, Z.; Lin, B.; Lai, L.; Ouyang, Z.; et al. Microplastic Particles Detected in Fetal Cord Blood, Placenta, and Meconium: A Pilot Study of Nine Mother-Infant Pairs in South China. Toxics 2024, 12, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Stenzel, M.H. Entry of Nanoparticles into Cells: The Importance of Nanoparticle Properties. Polym. Chem. 2018, 9, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firdessa, R.; Oelschlaeger, T.A.; Moll, H. Identification of Multiple Cellular Uptake Pathways of Polystyrene Nanoparticles and Factors Affecting the Uptake: Relevance for Drug Delivery Systems. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2014, 93, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, H.; Liu, X.; Qu, M. Nanoplastics and Human Health: Hazard Identification and Biointerface. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galloway, T.S. Micro- and Nano-Plastics and Human Health. In Marine Anthropogenic Litter; Bergmann, M., Gutow, L., Klages, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 343–366. ISBN 978-3-319-16510-3. [Google Scholar]

- Calzoni, E.; Montegiove, N.; Cesaretti, A.; Bertoldi, A.; Cusumano, G.; Gigliotti, G.; Emiliani, C. Microplastic and Extracellular Vesicle Interactions: Recent Studies on Human Health and Environment Risks. Biophysica 2024, 4, 724–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierzejewski, K.; Kurzyńska, A.; Golubska, M.; Całka, J.; Gałęcka, I.; Szabelski, M.; Paukszto, Ł.; Andronowska, A.; Bogacka, I. New Insights into the Potential Effects of PET Microplastics on Organisms via Extracellular Vesicle-Mediated Communication. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 904, 166967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vethaak, A.D.; Legler, J. Microplastics and Human Health. Science 2021, 371, 672–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issac, M.N.; Kandasubramanian, B. Effect of Microplastics in Water and Aquatic Systems. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021, 28, 19544–19562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochman, C.M.; Brookson, C.; Bikker, J.; Djuric, N.; Earn, A.; Bucci, K.; Athey, S.; Huntington, A.; McIlwraith, H.; Munno, K.; et al. Rethinking Microplastics as a Diverse Contaminant Suite. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2019, 38, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghe, S.; Stoica, C.; Harabagiu, A.M.; Neidoni, D.-G.; Mighiu, E.D.; Bumbac, C.; Ionescu, I.A.; Pantazi, A.; Enache, L.-B.; Enachescu, M. Laboratory Assessment for Determining Microplastics in Freshwater Systems—Characterization and Identification along the Somesul Mic River. Water 2024, 16, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, K.B.; Stephansen, D.A.; van Alst, N.; Vollertsen, J. Microplastics in a Stormwater Pond. Water 2019, 11, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Sheerin, E.D.; Shi, Y.; Xiao, L.; Yang, L.; Boland, J.J.; Wang, J.J. Alcohol Pretreatment to Eliminate the Interference of Micro Additive Particles in the Identification of Microplastics Using Raman Spectroscopy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 12158–12168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, L.; Gareb, F.E.; Zimmermann, T.; Klein, O.; Emeis, K.-C.; Proefrock, D.; Kerstan, A. Agilent Application Note: Fast, Automated Microplastics Analysis Using Laser Direct Chemical Imaging. 2020. Available online: https://www.agilent.com/cs/library/applications/application-marine-microplastics-8700-ldir-5994-2421en-agilent.pdf?srsltid=AfmBOoptLHTU7olCRzsiRZyvapQ1Z7gRKUmEryXZ_oyT7Npzvo91ZCcM (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Peel, R.H.; Lloyd, C.E.M.; Roberts, S.J.; Naafs, B.D.A.; Bull, I.D. Quantification of Microplastic Targets in Environmental Matrices Using Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2025, 4, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, K.; Zou, R.; Zhang, Z.; Mandemaker, L.D.B.; Timbie, S.; Smith, R.D.; Durkin, A.M.; Dusza, H.M.; Meirer, F.; Weckhuysen, B.M.; et al. Advancements in Assays for Micro- and Nanoplastic Detection: Paving the Way for Biomonitoring and Exposomics Studies. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2025, 65, 567–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Tang, X.; Gong, X.; Dai, Y.; Sun, H.; Wang, L. Development and Application of a Mass Spectrometry Method for Quantifying Nylon Microplastics in Environment. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 13930–13935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, R.; Wang, X.; Yang, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, N.; Xu, F.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L. Polystyrene Microplastics Cause Granulosa Cells Apoptosis and Fibrosis in Ovary through Oxidative Stress in Rats. Toxicology 2021, 449, 152665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, E.-J.; Han, J.-S.; Park, E.-J.; Seong, E.; Lee, G.-H.; Kim, D.-W.; Son, H.-Y.; Han, H.-Y.; Lee, B.-S. Repeated-Oral Dose Toxicity of Polyethylene Microplastics and the Possible Implications on Reproduction and Development of the next Generation. Toxicol. Lett. 2020, 324, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragusa, A.; Svelato, A.; Santacroce, C.; Catalano, P.; Notarstefano, V.; Carnevali, O.; Papa, F.; Rongioletti, M.C.A.; Baiocco, F.; Draghi, S.; et al. Plasticenta: First Evidence of Microplastics in Human Placenta. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aminah, I.S.; Ikejima, K. Potential Sources of Microplastic Contamination in Laboratory Analysis and a Protocol for Minimising Contamination. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, T.; Ehrlich, L.; Henrich, W.; Koeppel, S.; Lomako, I.; Schwabl, P.; Liebmann, B. Detection of Microplastic in Human Placenta and Meconium in a Clinical Setting. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, H.; Xu, P.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Y.; Ji, X.; Yan, R.; Yue, H.; Sang, N. Invisible Hand behind Female Reproductive Disorders: Bisphenols, Recent Evidence and Future Perspectives. Toxics 2023, 11, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Qin, Y.; Wang, M.; Xu, W.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, L.; Chen, W.; Luo, T. Microplastics from Agricultural Plastic Mulch Films: A Mini-Review of Their Impacts on the Animal Reproductive System. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 244, 114030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Manna, C.; Padha, S.; Verma, A.; Sharma, P.; Dhar, A.; Ghosh, A.; Bhattacharya, P. Micro(Nano)Plastics Pollution and Human. Health: How Plastics Can Induce Carcinogenesis to Humans? Chemosphere 2022, 298, 134267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böckers, M.; Paul, N.W.; Efferth, T. Organophosphate Ester Tri-o-Cresyl Phosphate Interacts with Estrogen Receptor α in MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells Promoting Cancer Growth. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2020, 395, 114977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Xie, J.; Han, Q.; Chen, M. Comparing the Effects of Polystyrene Microplastics Exposure on Reproduction and Fertility in Male and Female Mice. Toxicology 2022, 465, 153059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alchalabi, A.S.H.; Rahim, H.; Aklilu, E.; Al-Sultan, I.I.; Aziz, A.R.; Malek, M.F.; Ronald, S.H.; Khan, M.A. Histopathological Changes Associated with Oxidative Stress Induced by Electromagnetic Waves in Rats’ Ovarian and Uterine Tissues. Asian Pac. J. Reprod. 2016, 5, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhuan, Q.; Zhang, L.; Meng, L.; Fu, X.; Hou, Y. Polystyrene Microplastics Induced Female Reproductive Toxicity in Mice. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Kamstra, J.; Legler, J.; Aardema, H. The Impact of Microplastics on Female Reproduction and Early Life. Anim. Reprod. 2023, 20, e20230037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, H.J. Transzonal Projections: Essential Structures Mediating Intercellular Communication in the Mammalian Ovarian Follicle. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2022, 89, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanihara, F.; Nakai, M.; Men, N.T.; Kato, N.; Kaneko, H.; Noguchi, J.; Otoi, T.; Kikuchi, K. Roles of the Zona Pellucida and Functional Exposure of the Sperm-Egg Fusion Factor “IZUMO” during in Vitro Fertilization in Pigs. Anim. Sci. J. 2014, 85, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaulay, A.D.; Gilbert, I.; Caballero, J.; Barreto, R.; Fournier, E.; Tossou, P.; Sirard, M.-A.; Clarke, H.J.; Khandjian, É.W.; Richard, F.J.; et al. The Gametic Synapse: RNA Transfer to the Bovine Oocyte. Biol. Reprod. 2014, 91, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringfellow, D.A.; Givens, M.D. Manual of the International Embryo Transfer Society: A Procedural Guide and General Information for the Use of Embryo Transfer Technology Emphasizing Sanitary Procedures, 4th ed.; International Embryo Transfer Society: Savory, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vanroose, G.; Nauwynck, H.; Soom, A.V.; Ysebaert, M.T.; Charlier, G.; Oostveldt, P.V.; de Kruif, A. Structural Aspects of the Zona Pellucida of in Vitro-Produced Bovine Embryos: A Scanning Electron and Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopic Study. Biol. Reprod. 2000, 62, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arumugasaamy, N.; Rock, K.D.; Kuo, C.-Y.; Bale, T.L.; Fisher, J.P. Microphysiological Systems of the Placental Barrier. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020, 161–162, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dusza, H.M.; Manz, K.E.; Pennell, K.D.; Kanda, R.; Legler, J. Identification of Known and Novel Nonpolar Endocrine Disruptors in Human Amniotic Fluid. Environ. Int. 2022, 158, 106904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anifowoshe, A.T.; Akhtar, M.N.; Majeed, A.; Singh, A.S.; Ismail, T.F.; Nongthomba, U. Microplastics: A Threat to Fetoplacental Unit and Reproductive Systems. Toxicol. Rep. 2025, 14, 101938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafmueller, S.; Manser, P.; Diener, L.; Diener, P.-A.; Maeder-Althaus, X.; Maurizi, L.; Jochum, W.; Krug, H.F.; Buerki-Thurnherr, T.; von Mandach, U.; et al. Bidirectional Transfer Study of Polystyrene Nanoparticles across the Placental Barrier in an Ex Vivo Human Placental Perfusion Model. Environ. Health Perspect. 2015, 123, 1280–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragusa, A.; Matta, M.; Cristiano, L.; Matassa, R.; Battaglione, E.; Svelato, A.; De Luca, C.; D’Avino, S.; Gulotta, A.; Rongioletti, M.C.A.; et al. Deeply in Plasticenta: Presence of Microplastics in the Intracellular Compartment of Human Placentas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.-H.; Shen, Y.; Roshdy, M.; Cheng, X.; Wang, G.; Yang, X. Polystyrene Nanoplastics Exposure Caused Defective Neural Tube Morphogenesis through Caveolae-Mediated Endocytosis and Faulty Apoptosis. Nanotoxicology 2021, 15, 885–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Qin, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zeng, W.; Lin, Y.; Liu, X. Polystyrene Microplastics Disturb Maternal-Fetal Immune Balance and Cause Reproductive Toxicity in Pregnant Mice. Reprod. Toxicol. 2021, 106, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaei, Z.; Mercer, G.V.; Schneider, C.M.; Sled, J.G.; Macgowan, C.K.; Baschat, A.A.; Kingdom, J.C.; Helm, P.A.; Simpson, A.J.; Simpson, M.J.; et al. Maternal Exposure to Polystyrene Microplastics Alters Placental Metabolism in Mice. Metabolomics 2022, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Xiong, S.; Jing, Q.; van Gestel, C.A.M.; van Straalen, N.M.; Roelofs, D.; Sun, L.; Qiu, H. Maternal Exposure to Polystyrene Nanoparticles Retarded Fetal Growth and Triggered Metabolic Disorders of Placenta and Fetus in Mice. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 854, 158666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridder, A.; Giorgione, V.; Khalil, A.; Thilaganathan, B. Preeclampsia: The Relationship between Uterine Artery Blood Flow and Trophoblast Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaei, Z.; Sled, J.G.; Kingdom, J.C.; Baschat, A.A.; Helm, P.A.; Jobst, K.J.; Cahill, L.S. Maternal Exposure to Polystyrene Micro- and Nanoplastics Causes Fetal Growth Restriction in Mice. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2022, 9, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yu, T.; Yao, Y.; Zhao, R.; Yu, R.; Liu, J.; Su, J. Reproductive Toxicity of Microplastics in Female Mice and Their Offspring from Induction of Oxidative Stress. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 327, 121482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Zhang, W.; Lin, T.; Liu, S.; Sun, Z.; Liu, F.; Yuan, Y.; Xiang, X.; Kuang, H.; Yang, B.; et al. Maternal Exposure to Polystyrene Nanoplastics during Gestation and Lactation Induces Hepatic and Testicular Toxicity in Male Mouse Offspring. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 160, 112803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, X.; Pan, D.; Nan, S.; Yin, R.; Lei, Q.; Ma, N.; Zhu, H.; Chen, J.; et al. Polystyrene Micro- and Nano-Particle Coexposure Injures Fetal Thalamus by Inducing ROS-Mediated Cell Apoptosis. Environ. Int. 2022, 166, 107362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |