Nanoplastic Contamination Across Common Beverages and Infant Food: An Assessment of Packaging Influence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

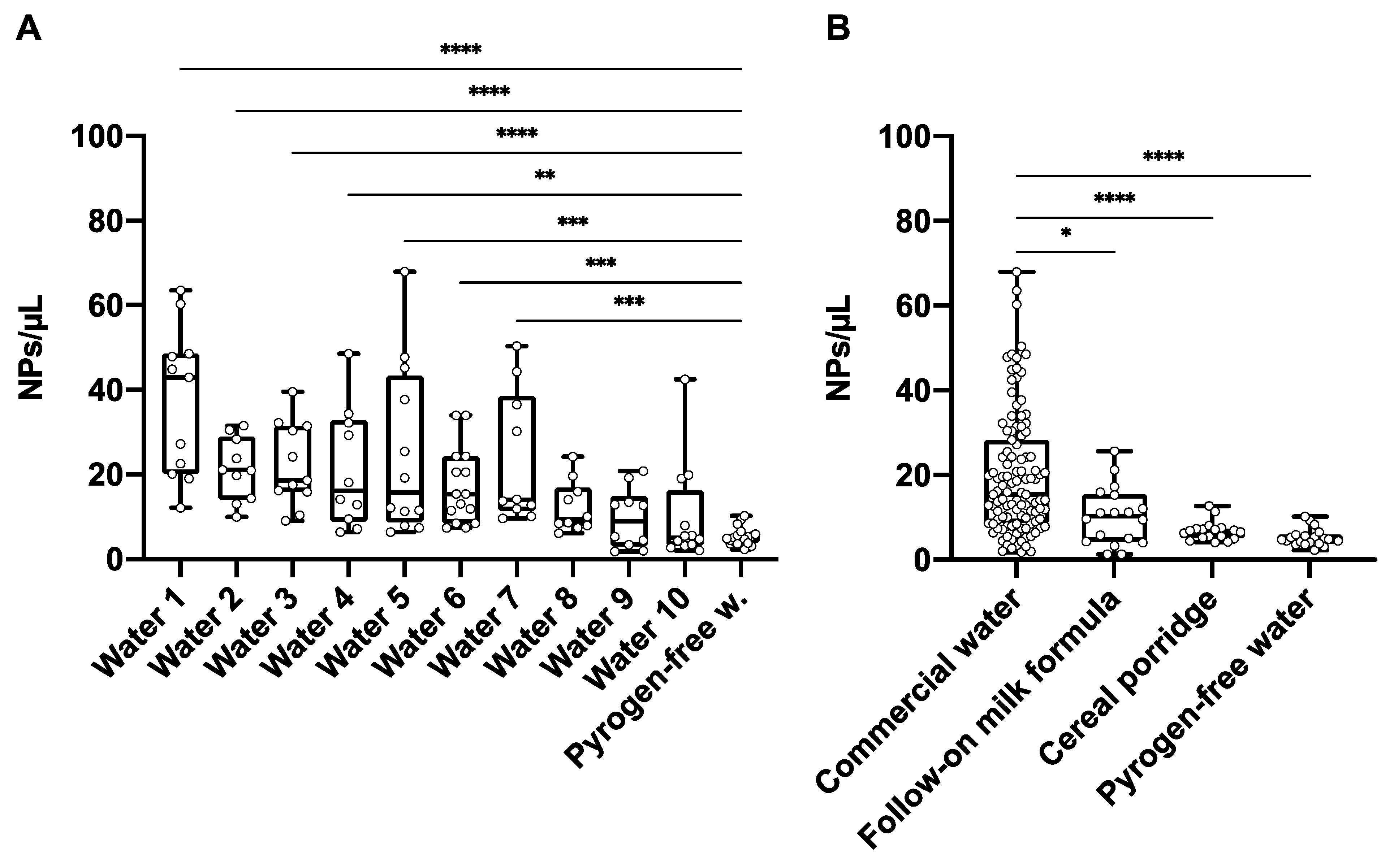

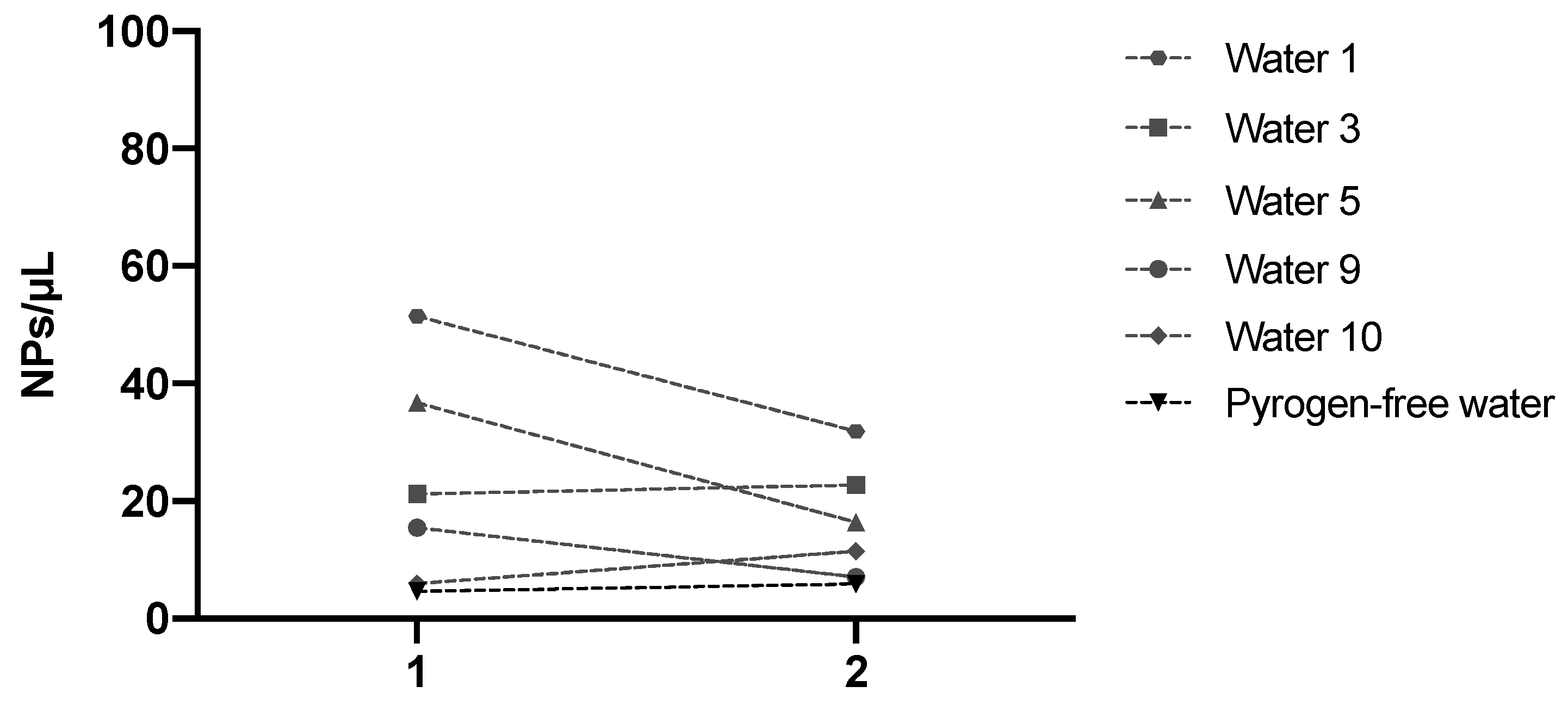

3.1. Nanoplastic Contamination in Commercial Waters

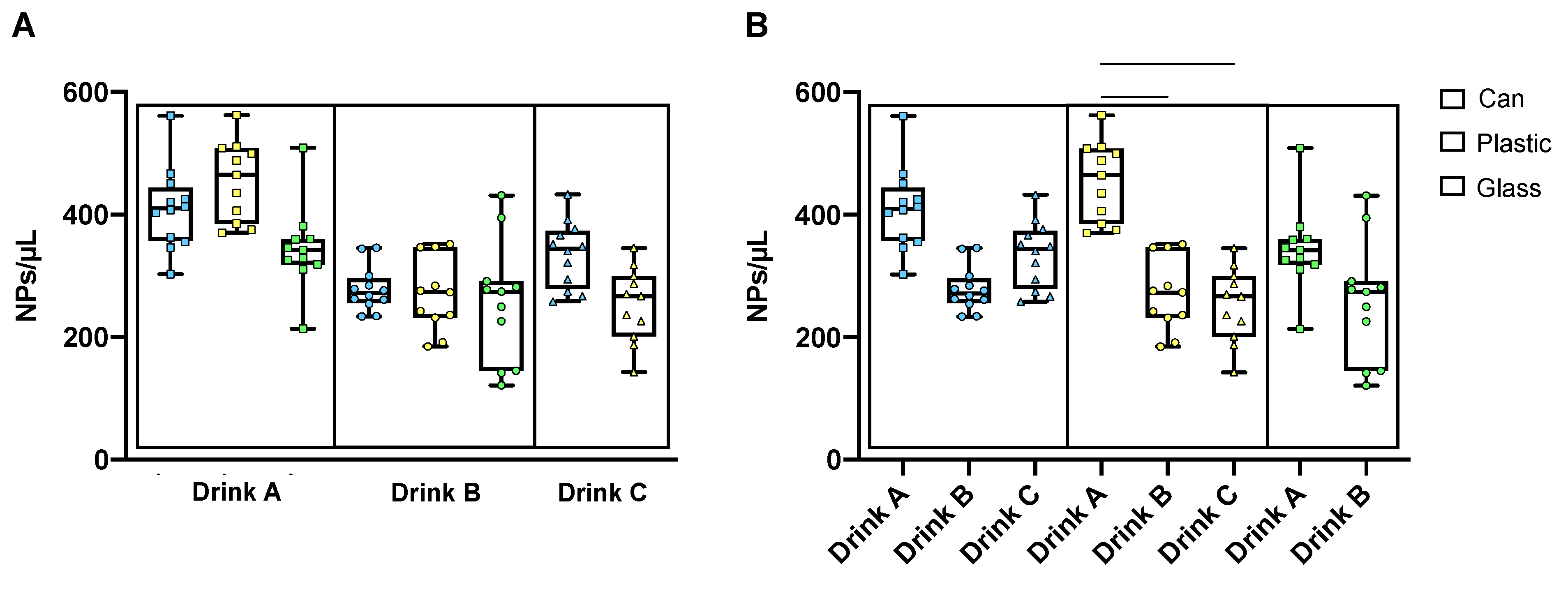

3.2. Nanoplastic Contamination in Infant Formula, Cereal Porridge and Carbonated Beverages

3.3. Significance of Nanoplastic Levels in Commercial Bottled Waters and Beverages: Sources, Variability, and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Y.; Tao, L.; Wang, Q.; Wang, F.; Li, G.; Song, M. Potential Health Impact of Microplastics: A Review of Environmental Distribution, Human Exposure, and Toxic Effects. Environ. Health 2023, 1, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, R.C.; Olsen, Y.; Mitchell, R.P.; Davis, A.; Rowland, S.J.; John, A.W.G.; McGonigle, D.; Russell, A.E. Lost at Sea: Where Is All the Plastic? Science 2004, 304, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolaosho, T.L.; Rasaq, M.F.; Omotoye, E.V.; Araomo, O.V.; Adekoya, O.S.; Abolaji, O.Y.; Hungbo, J.J. Microplastics in freshwater and marine ecosystems: Occurrence, characterization, sources, distribution dynamics, fate, transport processes, potential mitigation strategies, and policy interventions. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 294, 118036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gigault, J.; ter Halle, A.; Baudrimont, M.; Pascal, P.-Y.; Gauffre, F.; Phi, T.-L.; El Hadri, H.; Grassl, B.; Reynaud, S. Current opinion: What is a nanoplastic? Environ. Pollut. 2018, 235, 1030–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigault, J.; El Hadri, H.; Nguyen, B.; Grassl, B.; Rowenczyk, L.; Tufenkji, N.; Feng, S.; Wiesner, M. Nanoplastics are neither microplastics nor engineered nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, J.; Friot, D. Primary Microplastics in the Oceans: A Global Evaluation of Sources; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2017; p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Nawab, A.; Ahmad, M.; Khan, M.T.; Nafees, M.; Khan, I.; Ihsanullah, I. Human exposure to microplastics: A review on exposure routes and public health impacts. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2024, 16, 100487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cauwenberghe, L.; Janssen, C.R. Microplastics in bivalves cultured for human consumption. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 193, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirstein, I.V.; Gomiero, A.; Vollertsen, J. Microplastic pollution in drinking water. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2021, 28, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wong, K.K.; Li, W.; Zhao, H.; Wang, T.; Stanescu, S.; Boult, S.; van Dongen, B.; Mativenga, P.; Li, L. Characteristics of nano-plastics in bottled drinking water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, S.A.; Welch, V.G.; Neratko, J. Synthetic Polymer Contamination in Bottled Water. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancaleone, E.; Mattei, D.; Fuscoletti, V.; Lucentini, L.; Favero, G.; Cecchini, G.; Frugis, A.; Gioia, V.; Lazzazzara, M. Microplastic in Drinking Water: A Pilot Study. Microplastics 2024, 3, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, T.R. Additive Migration from Plastics into Foods. A Guide for Analytical Chemists, 1st ed.; Smithers Rapra Technology: Shrewsbury, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Waring, R.; Harris, R.; Mitchell, S. Plastic contamination of the food chain: A threat to human health? Maturitas 2018, 115, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-L.; Lee, Y.-H.; Chiu, I.-J.; Lin, Y.-F.; Chiu, H.-W. Potent Impact of Plastic Nanomaterials and Micromaterials on the Food Chain and Human Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberdörster, G.; Elder, A.; Rinderknecht, A. Nanoparticles and the Brain: Cause for Concern? J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2009, 9, 4996–5007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukkola, A.; Chetwynd, A.J.; Krause, S.; Lynch, I. Beyond microbeads: Examining the role of cosmetics in microplastic pollution and spotlighting unanswered questions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 476, 135053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanale, C.; Massarelli, C.; Savino, I.; Locaputo, V.; Uricchio, V.F. A Detailed Review Study on Potential Effects of Microplastics and Additives of Concern on Human Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragusa, A.; Svelato, A.; Santacroce, C.; Catalano, P.; Notarstefano, V.; Carnevali, O.; Papa, F.; Rongioletti, M.C.A.; Baiocco, F.; Draghi, S.; et al. Plasticenta: First evidence of microplastics in human placenta. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-S.; Chang, C.-H.; Tsai, P.-J.; Chen, W.-Y.; Tseng, F.-G.; Lo, L.-W. Nanoparticle-Based in Vivo Investigation on Blood−Brain Barrier Permeability Following Ischemia and Reperfusion. Anal. Chem. 2004, 76, 4465–4471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zeng, T.; Zhao, X. Polystyrene nanoplastics penetrate across the blood-brain barrier and induce activation of microglia in the brain of mice. Chemosphere 2022, 298, 134261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, C.Q.Y.; Valiyaveettil, S.; Tang, B.L. Toxicity of Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Mammalian Systems. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwabl, P.; Köppel, S.; Königshofer, P.; Bucsics, T.; Trauner, M.; Reiberger, T.; Liebmann, B. Detection of Various Microplastics in Human Stool. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 171, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habumugisha, T.; Zhang, Z.; Uwizewe, C.; Yan, C.; Ndayishimiye, J.C.; Rehman, A.; Zhang, X. Toxicological review of micro- and nano-plastics in aquatic environments: Risks to ecosystems, food web dynamics and human health. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 278, 116426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, A.A.; Walton, A.; Spurgeon, D.J.; Lahive, E.; Svendsen, C. Microplastics in freshwater and terrestrial environments: Evaluating the current understanding to identify the knowledge gaps and future research priorities. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 586, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirelli, V.; Grasso, F.; Barreca, V.; Polignano, D.; Gallinaro, A.; Cara, A.; Sargiacomo, M.; Fiani, M.L.; Sanchez, M. Flow cytometric procedures for deep characterization of nanoparticles. Biol. Methods Protoc. 2025, 10, bpaf019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, N.; Catarino, A.I.; Declercq, A.M.; Brenan, A.; Devriese, L.; Vandegehuchte, M.; De Witte, B.; Janssen, C.; Everaert, G. Microplastic detection and identification by Nile red staining: Towards a semi-automated, cost- and time-effective technique. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 823, 153441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvia, R.; Rico, L.G.; Bradford, J.A.; Ward, M.D.; Olszowy, M.W.; Martínez, C.; Madrid-Aris, Á.D.; Grífols, J.R.; Ancochea, Á.; Gomez-Muñoz, L.; et al. Fast-screening flow cytometry method for detecting nanoplastics in human peripheral blood. MethodsX 2023, 10, 102057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, L.; Ma, M.; Wu, H.; An, L.; Yang, Z. Occurrence of microplastics in commercially sold bottled water. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 867, 161553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oßmann, B.E.; Sarau, G.; Holtmannspötter, H.; Pischetsrieder, M.; Christiansen, S.H.; Dicke, W. Small-sized microplastics and pigmented particles in bottled mineral water. Water Res. 2018, 141, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.R.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; Narayan, R.; Law, K.L. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziani, K.; Ioniță-Mîndrican, C.-B.; Mititelu, M.; Neacșu, S.M.; Negrei, C.; Moroșan, E.; Drăgănescu, D.; Preda, O.-T. Microplastics: A Real Global Threat for Environment and Food Safety: A State of the Art Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammodat, A.R.; Nassar, S.; Mortula, M.; Shamsuzzaman, M. Factors affecting the leaching of micro and nanoplastics in the water distribution system. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, N.; Gao, X.; Lang, X.; Deng, H.; Bratu, T.M.; Chen, Q.; Stapleton, P.; Yan, B.; Min, W. Rapid single-particle chemical imaging of nanoplastics by SRS microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2300582121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steimel, K.G.; Hwang, R.; Dinh, D.; Donnell, M.T.; More, S.; Fung, E. Evaluation of chemicals leached from PET and recycled PET containers into beverages. Rev. Environ. Health 2024, 39, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, K.K. Microplastic pollution in bottled water: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 22, 1283–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahladakis, J.N.; Velis, C.A.; Weber, R.; Iacovidou, E.; Purnell, P. An overview of chemical additives present in plastics: Migration, release, fate and environmental impact during their use, disposal and recycling. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 344, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xu, M.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, B. On the degradation of (micro)plastics: Degradation methods, influencing factors, environmental impacts. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 151312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, C.; Dauchy, X.; Severin, I.; Munoz, J.-F.; Etienne, S.; Chagnon, M.-C. Effect of temperature on the release of intentionally and non-intentionally added substances from polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles into water: Chemical analysis and potential toxicity. Food Chem. 2013, 139, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerhoff, P.; Prapaipong, P.; Shock, E.; Hillaireau, A. Antimony leaching from polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastic used for bottled drinking water. Water Res. 2008, 42, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keresztes, S.; Tatár, E.; Mihucz, V.G.; Virág, I.; Majdik, C.; Záray, G. Leaching of antimony from polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles into mineral water. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 4731–4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Oehlmann, J. Endocrine disruptors in bottled mineral water: Total estrogenic burden and migration from plastic bottles. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2009, 16, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Gao, S.-H.; Ge, C.; Gao, Q.; Huang, S.; Kang, Y.; Luo, G.; Zhang, Z.; Fan, L.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Removing microplastics from aquatic environments: A critical review. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 2022, 13, 100222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Love, D.C.; Rochman, C.M.; Neff, R.A. Microplastics in Seafood and the Implications for Human Health. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2018, 5, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salvia, R.; Soriano, C.; Casanovas, I.; Sorigué, M.; Evans, E.; de Pablo, J.G.; Ward, M.D.; Petriz, J. Nanoplastic Contamination Across Common Beverages and Infant Food: An Assessment of Packaging Influence. Microplastics 2025, 4, 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/microplastics4040108

Salvia R, Soriano C, Casanovas I, Sorigué M, Evans E, de Pablo JG, Ward MD, Petriz J. Nanoplastic Contamination Across Common Beverages and Infant Food: An Assessment of Packaging Influence. Microplastics. 2025; 4(4):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/microplastics4040108

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalvia, Roser, Carlos Soriano, Irene Casanovas, Marc Sorigué, Emily Evans, Julia Gala de Pablo, Michael D. Ward, and Jordi Petriz. 2025. "Nanoplastic Contamination Across Common Beverages and Infant Food: An Assessment of Packaging Influence" Microplastics 4, no. 4: 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/microplastics4040108

APA StyleSalvia, R., Soriano, C., Casanovas, I., Sorigué, M., Evans, E., de Pablo, J. G., Ward, M. D., & Petriz, J. (2025). Nanoplastic Contamination Across Common Beverages and Infant Food: An Assessment of Packaging Influence. Microplastics, 4(4), 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/microplastics4040108