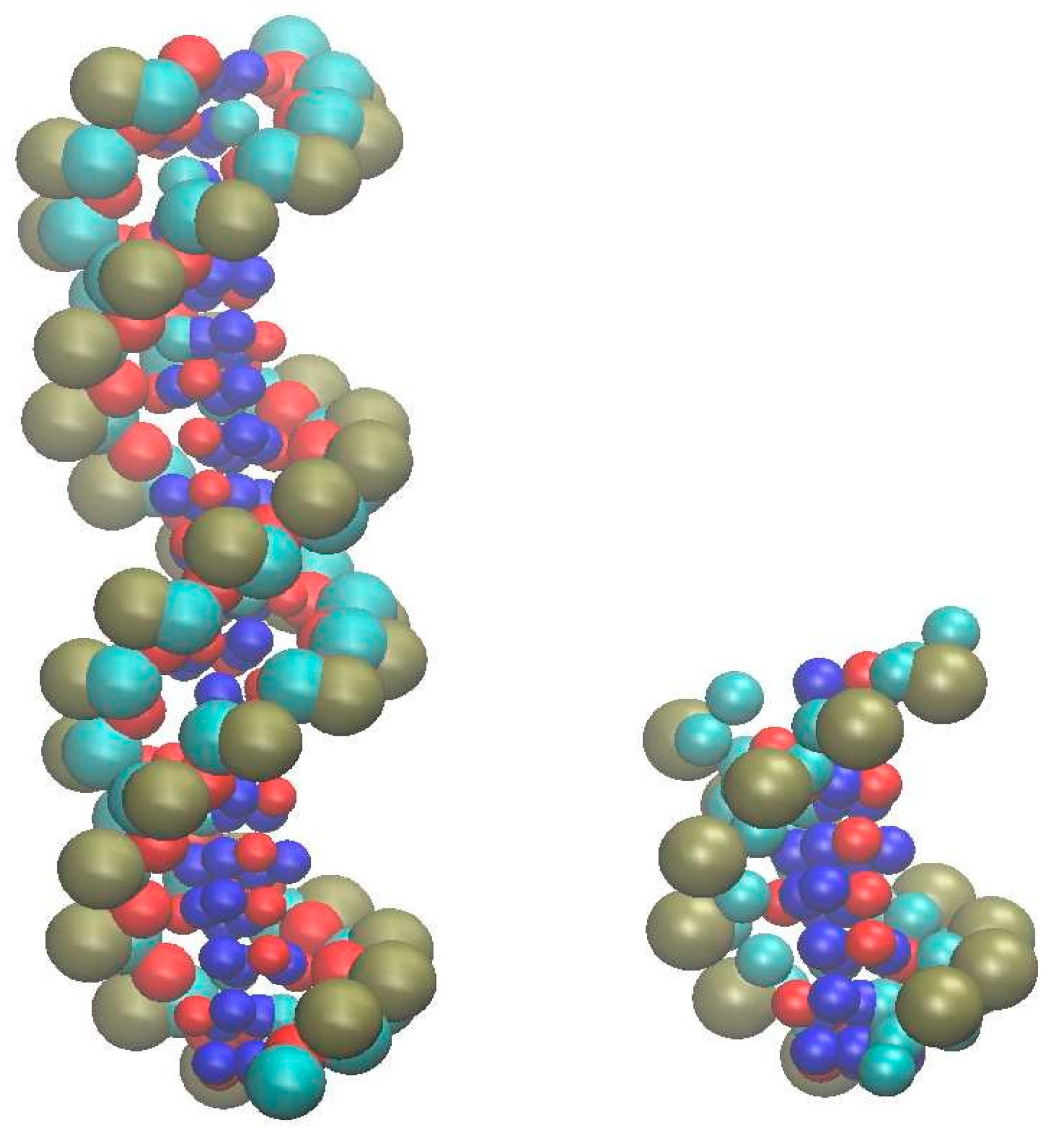

Using the SIRAH Force-Field to Model Interactions Between Short DNA Duplexes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

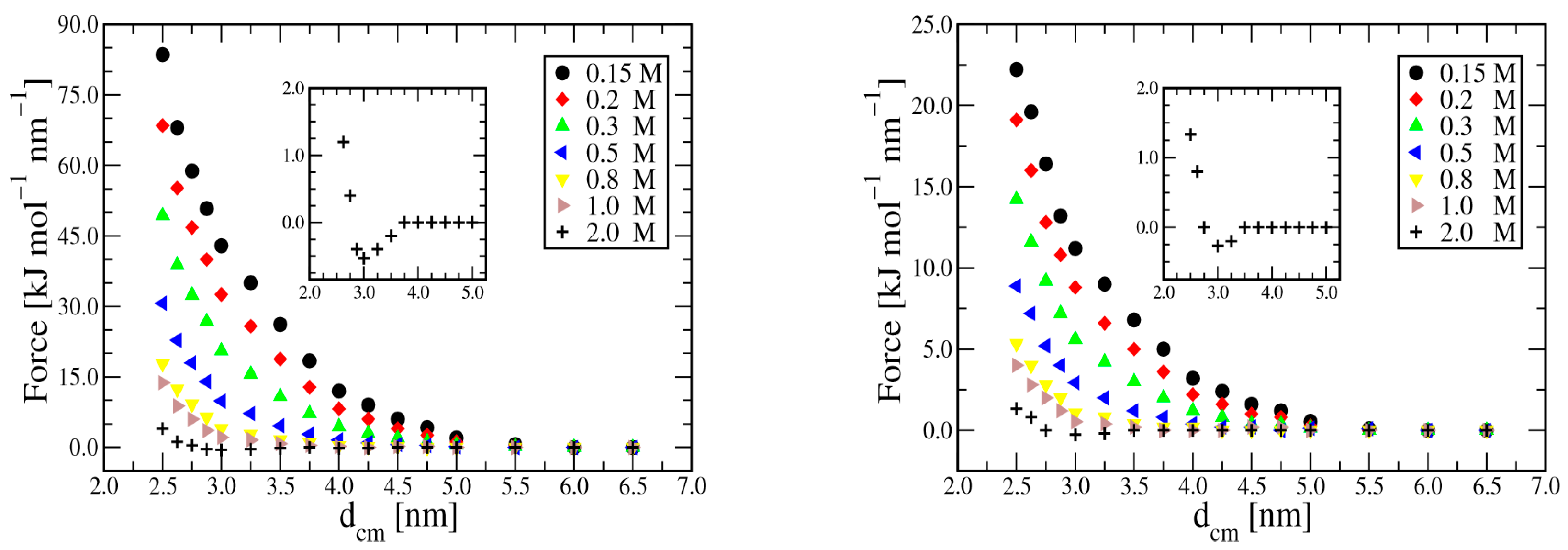

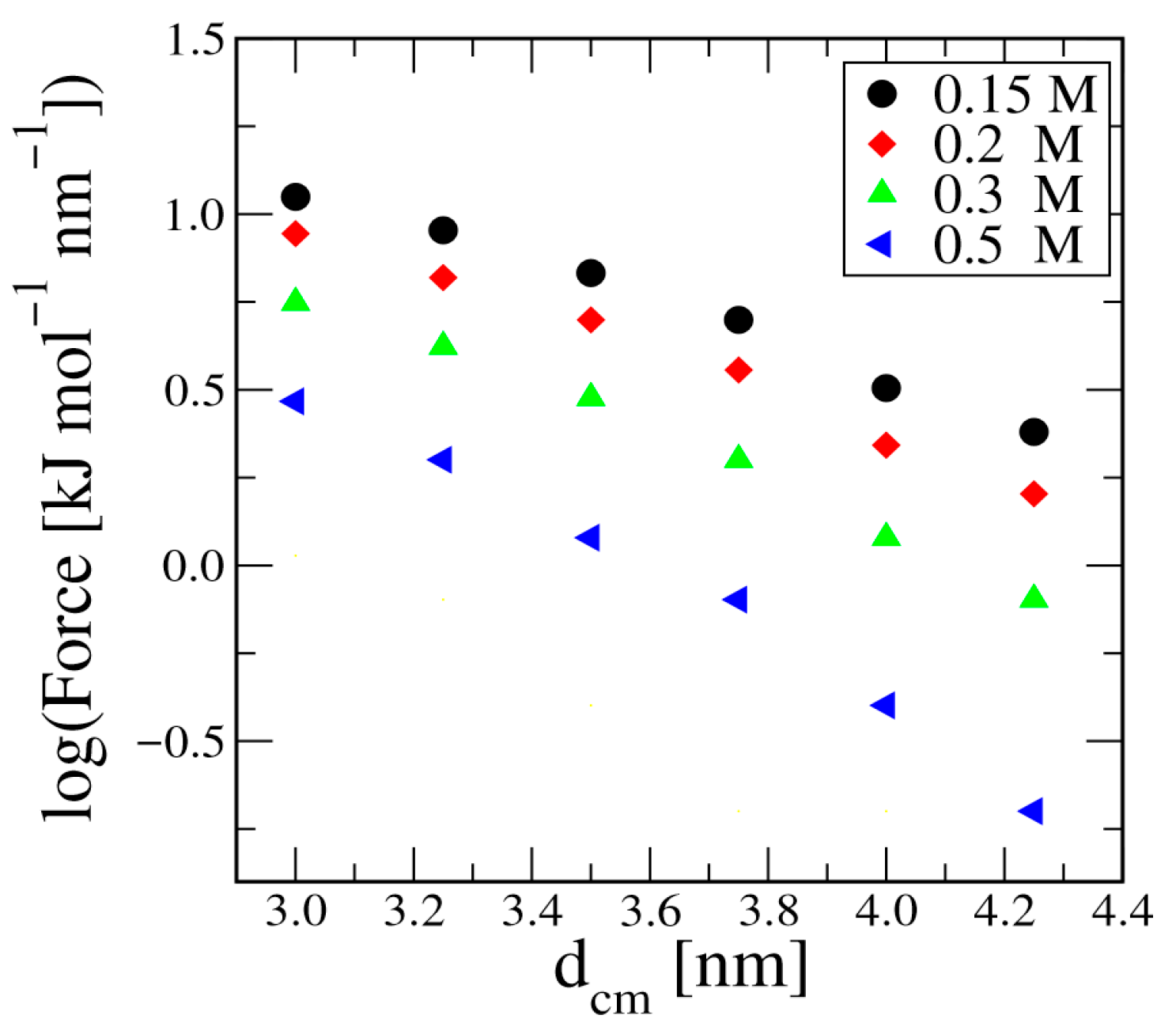

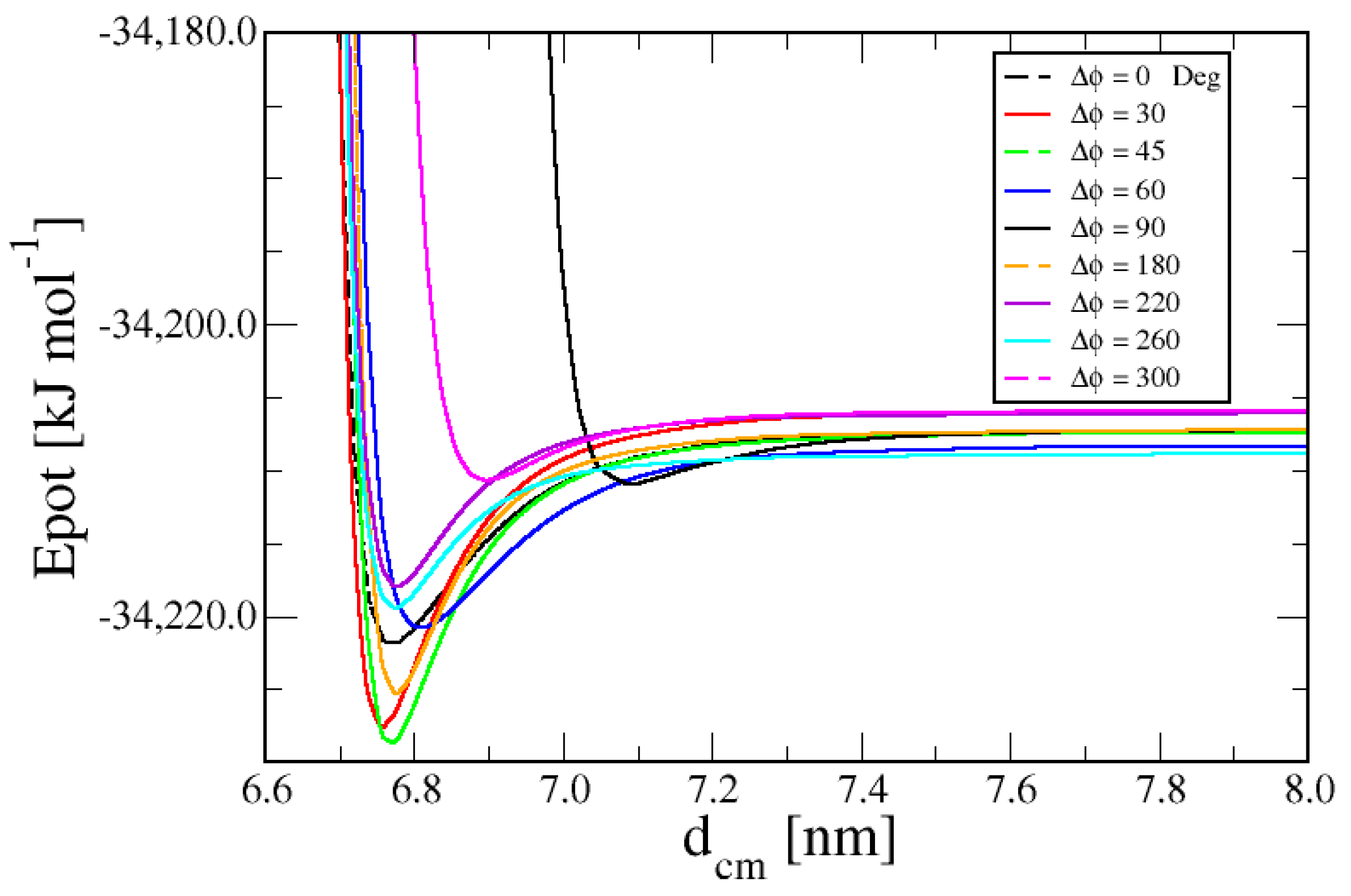

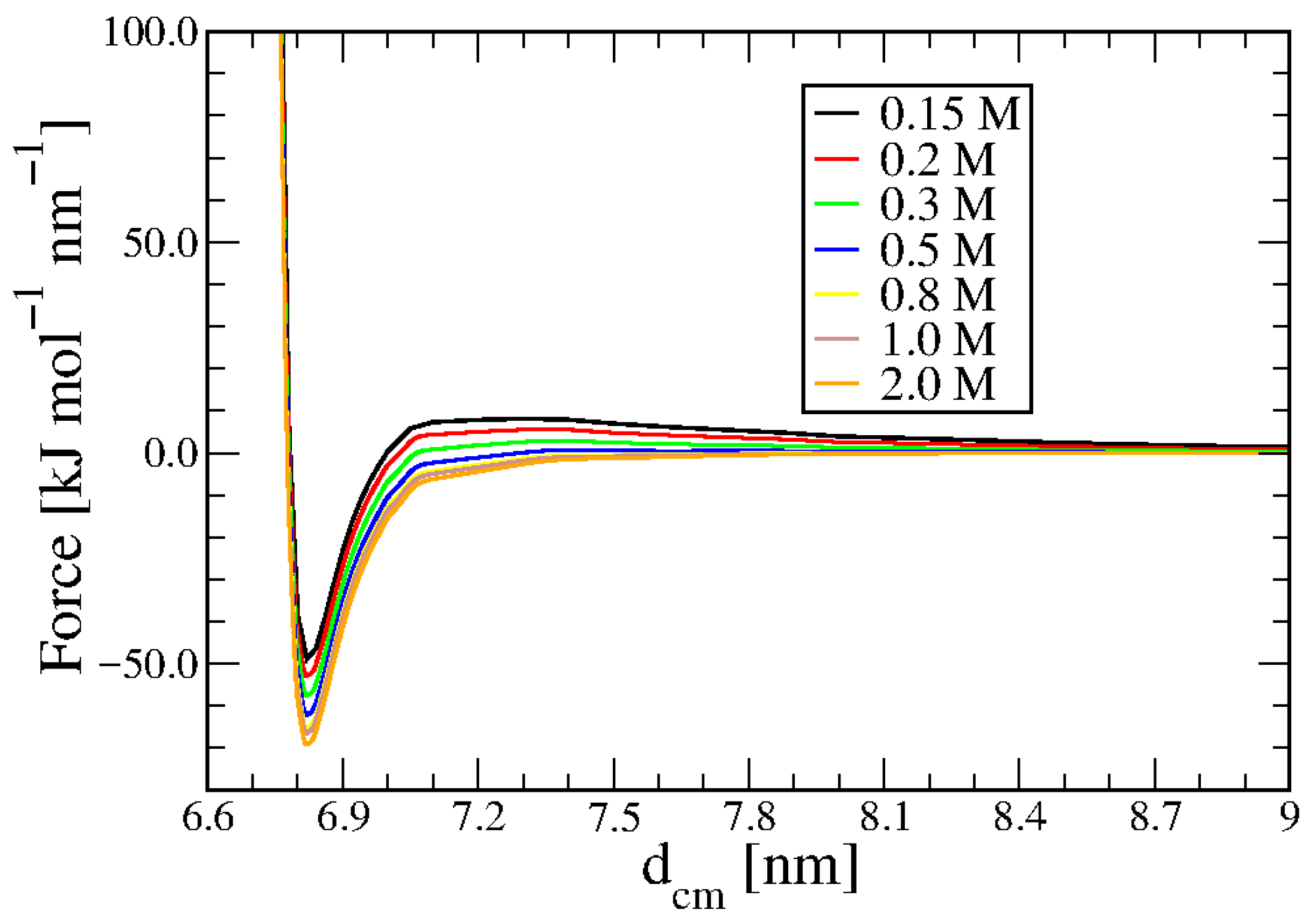

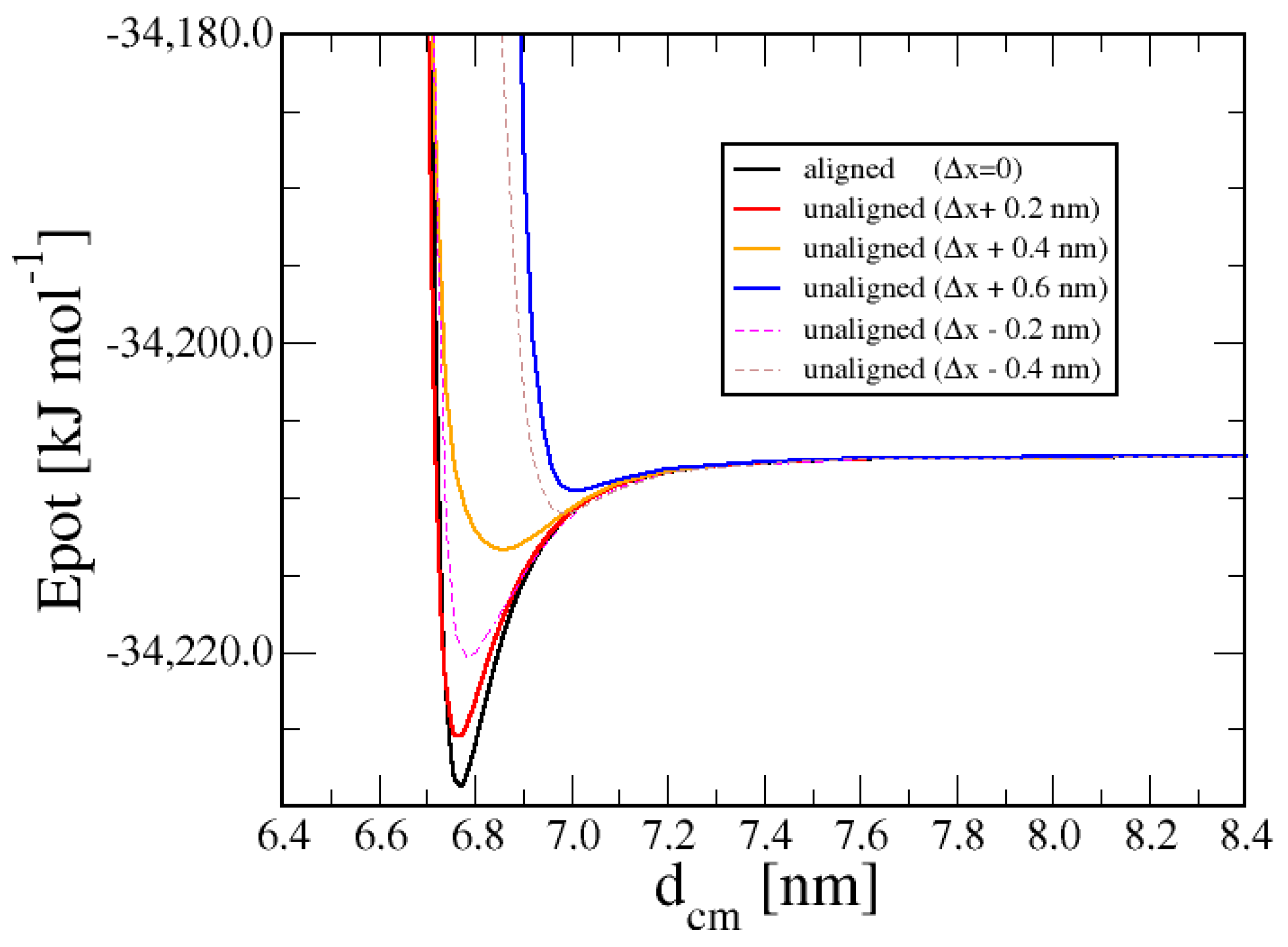

3.1. Duplex–Duplex Interaction

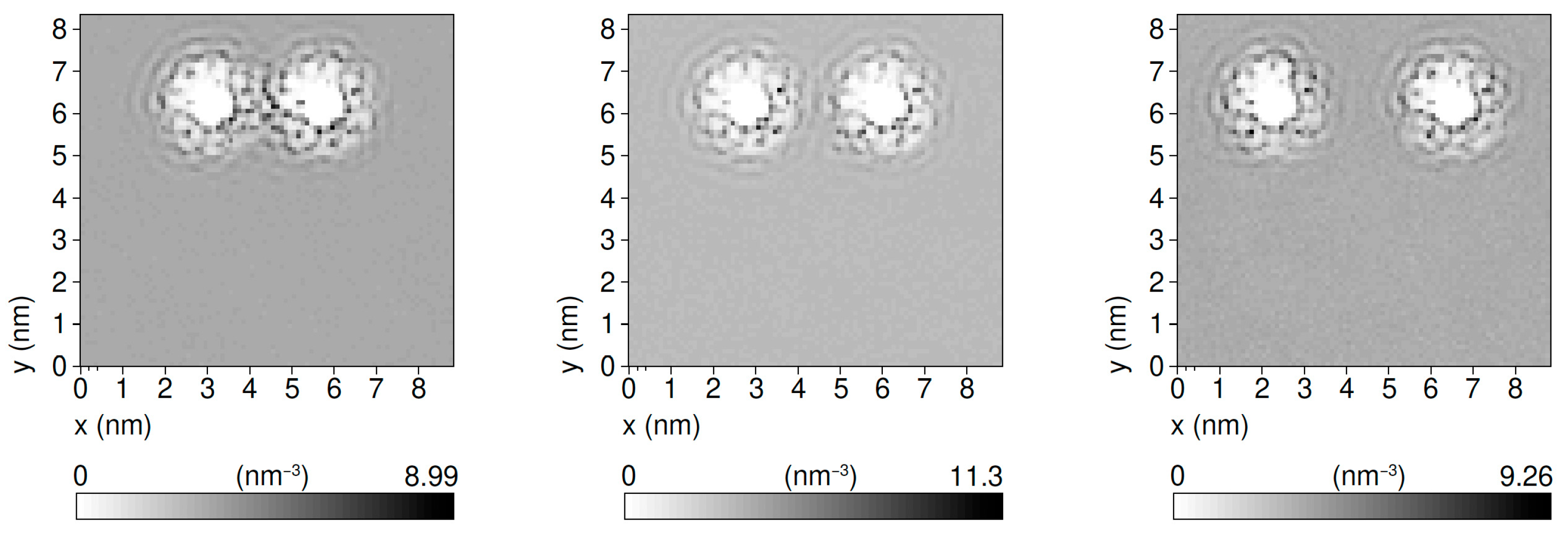

3.2. Effects of Solvent Density

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LC | Liquid crystal |

| bp | Base pairs |

| ds | Double strand |

| CG | Coarse-grained |

| SIRAH | South-American Initiative for a Rapid and Accurate Hamiltonian |

References

- Pedersen, R.; Marchi, A.N.; Majikes, J.; Nash, J.A.; Estrich, N.A.; Courson, D.S.; Hall, C.K.; Craig, S.L.; Labean, T.H. Properties of DNA. In Handbook of Nanomaterials Properties; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 1125–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrikse, S.I.; Gras, S.L.; Ellis, A.V. Opportunities and challenges in DNA-hybrid nanomaterials. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 8512–8516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linko, V.; Dietz, H. The enabled state of DNA nanotechnology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2013, 24, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bath, J.; Turberfield, A.J. DNA nanomachines. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2007, 2, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liedl, T.; Sobey, T.L.; Simmel, F.C. DNA-based nanodevices. Nano Today 2007, 2, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, T.; Cerbino, R.; Zanchetta, G. DNA-based soft phases. In Liquid Crystals; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 225–279. [Google Scholar]

- De Michele, C.; Bellini, T.; Sciortino, F. Self-assembly of bifunctional patchy particles with anisotropic shape into polymers chains: Theory, simulations, and experiments. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 1090–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.T.; Sciortino, F.; De Michele, C. Self-assembly-driven nematization. Langmuir 2014, 30, 4814–4819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Michele, C.; Rovigatti, L.; Bellini, T.; Sciortino, F. Self-assembly of short DNA duplexes: From a coarse-grained model to experiments through a theoretical link. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 8388–8398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcock, C.L.; Ghosh, R.P. Chromatin higher-order structure and dynamics. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010, 2, a000596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Filippo, J.; Sung, P.; Klein, H. Mechanism of eukaryotic homologous recombination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008, 77, 229–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.P.; Bartek, J. The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature 2009, 461, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurabh, S.; Lansac, Y.; Jang, Y.H.; Glaser, M.A.; Clark, N.A.; Maiti, P.K. Understanding the origin of liquid crystal ordering of ultrashort double-stranded DNA. Phys. Rev. E 2017, 95, 032702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naskar, S.; Saurabh, S.; Jang, Y.H.; Lansac, Y.; Maiti, P.K. Liquid crystal ordering of nucleic acids. Soft Matter 2020, 16, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savelyev, A.; Papoian, G.A. Chemically accurate coarse graining of double-stranded DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 20340–20345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uusitalo, J.J.; Ingólfsson, H.I.; Akhshi, P.; Tieleman, D.P.; Marrink, S.J. Martini coarse-grained force field: Extension to DNA. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 3932–3945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouldridge, T.E.; Louis, A.A.; Doye, J.P. Structural, mechanical, and thermodynamic properties of a coarse-grained DNA model. J. Chem. Phys. 2011, 134, 025101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doye, J.P.; Ouldridge, T.E.; Louis, A.A.; Romano, F.; Šulc, P.; Matek, C.; Snodin, B.E.; Rovigatti, L.; Schreck, J.S.; Harrison, R.M.; et al. Coarse-graining DNA for simulations of DNA nanotechnology. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 20395–20414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dans, P.D.; Zeida, A.; Machado, M.R.; Pantano, S. A coarse grained model for atomic detailed DNA simulations with explicit electrostatics. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010, 6, 1711–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, M.R.; Dans, P.D.; Pantano, S. A hybrid all-atom/coarse grain model for multiscale simulations of DNA. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 18134–18144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dans, P.D.; Darré, L.; Machado, M.R.; Zeida, A.; Brandner, A.F.; Pantano, S. Assessing the accuracy of the SIRAH force field to model DNA at coarse grain level. In Brazilian Symposium on Bioinformatics Lecture Notes in Computer Science Advances in Bioinformatics and Computational Biology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2013; pp. 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noid, W.G. Perspective: Coarse-grained models for biomolecular systems. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 139, 090901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanchetta, G.; Giavazzi, F.; Nakata, M.; Buscaglia, M.; Cerbino, R.; Clark, N.A.; Bellini, T. Right-handed double-helix ultrashort DNA yields chiral nematic phases with both right-and lefthanded director twist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 17497–17502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frezza, E.; Tombolato, F.; Ferrarini, A. Right-and left-handed liquid crystal assemblies of oligonucleotides: Phase chirality as a reporter of a change in non-chiral interactions? Soft Matter 2011, 7, 9291–9296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Thorpe, I.F.; Izvekov, S.; Voth, G.A. Coarse-grained peptide modeling using a systematic multiscale approach. Biophys. J. 2007, 92, 4289–4303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potoyan, D.A.; Savelyev, A.; Papoian, G.A. Recent successes in coarse-grained modeling of DNA. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2013, 3, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, G.D.; Cramer, C.J.; Truhlar, D.G. Parametrized models of aqueous free energies of solvation based on pairwise descreening of solute atomic charges from a dielectric medium. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 19824–19839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darré, L.; Machado, M.R.; Dans, P.D.; Herrera, F.E.; Pantano, S. Another coarse grain model for aqueous solvation: WAT FOUR? J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010, 6, 3793–3803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlman, D.A.; Case, D.A.; Caldwell, J.W.; Ross, W.S.; Cheatham, T.E., III; DeBolt, S.; Ferguson, D.; Seibel, G.; Kollman, P. Amber, a package of computer programs for applying molecular mechanics, normal mode analysis, molecular dynamics and free energy calculations to simulate the structural and energetic properties of molecules. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1995, 91, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, D.A.; Cheatham, T.E., III; Darden, T.; Gohlke, H.; Luo, R.; Merz, K.M., Jr.; Onufriev, A.; Simmerling, C.B.; Wang, B.; Woods, R.J. The amber biomolecular simulation programs. J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 1668–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.P.; Tildesley, D.J. Computer Simulation of Liquids, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen, H.J.; van der Spoel, D.; van Drunen, R. Gromacs: A message-passing parallel molecular dynamics implementation. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1995, 91, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgornik, R.; Rau, D.C.; Parsegian, V.A. Parametrization of direct and soft steric undulatory forces between DNA double helical polyelectrolytes in solutions of several different anions and cations. Biophys. J. 1994, 66, 962–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornyshev, A.A.; Leikin, S. Theory of interaction between helical molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1997, 107, 3656–3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornyshev, A.A.; Leikin, S. Electrostatic interaction between long, rigid helical macromolecules at all interaxial angles. Phys. Rev. E 2000, 62, 2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maffeo, C.; Luan, B.; Aksimentiev, A. End-to-end attraction of duplex DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 3812–3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snodin, B.E.K.; Randisi, F.; Mosayebi, M.; Šulc, P.; Schreck, J.S.; Romano, F.; Ouldridge, T.E.; Tsukanov, R.; Nir, E.; Louis, A.A.; et al. Introducing improved structural properties and salt dependence into a coarse grained model of DNA. J. Chem. Phys. 2015, 142, 234901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Girard, M.; Shen, M.; Olvera de la Cruz, M. Strong attractions and repulsions mediated by monovalent salts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 12338–12343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Tian, F.-J.; Zuo, H.-W.; Qiu, Q.-Y.; Zhang, J.-H.; Wei, W.; Tan, Z.-J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, W.-Q.; Dai, L.; et al. Counterintuitive DNA destabilization by monovalent salt at high concentrations due to overcharging. Nat. Commun. 2025, 15, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Mu, Y.; Nordenskiöld, L.; van der Maarel, J.R. Molecular dynamics simulation of multivalent-ion mediated attraction between DNA molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 118301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strey, H.H.; Podgornik, R.; Rau, D.C.; Parsegian, V.A. DNA-DNA Interactions. Curr. Opin. in Struct. Biol. 1998, 8, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanduč, M.; Dobnikar, J.; Podgornik, R. Counterion-mediated electrostatic interactions between helical molecules. Soft Matter 2009, 5, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahyarov, E.; Löwen, H. Effective interaction between helical biomolecules. Physical Review E 2000, 62, 5542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duboué-Dijon, E.; Fogarty, A.C.; Hynes, J.T.; Laage, D. Dynamical Disorder in the DNA Hydration Shell. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 7610–7620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hud, N.V.; Polak, M. DNA-Cation Interactions: The Major and Minor Grooves Are Flexible Ionophores. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001, 11, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, K.; Qiu, X.; Pabit, S.A.; Lamb, J.S.; Park, H.Y.; Kwok, L.W.; Pollack, L. Mono and trivalent ions around DNA: A small-angle scattering study of competition and interactions. Biophys. J. 2008, 95, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ruberto, R.; Smargiassi, E.; Pastore, G. Using the SIRAH Force-Field to Model Interactions Between Short DNA Duplexes. DNA 2026, 6, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/dna6010008

Ruberto R, Smargiassi E, Pastore G. Using the SIRAH Force-Field to Model Interactions Between Short DNA Duplexes. DNA. 2026; 6(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/dna6010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuberto, Romina, Enrico Smargiassi, and Giorgio Pastore. 2026. "Using the SIRAH Force-Field to Model Interactions Between Short DNA Duplexes" DNA 6, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/dna6010008

APA StyleRuberto, R., Smargiassi, E., & Pastore, G. (2026). Using the SIRAH Force-Field to Model Interactions Between Short DNA Duplexes. DNA, 6(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/dna6010008