Highlights

- The type II V arms for each synonymous tRNA set (i.e., in Archaea, 5 tRNALeu and 4 tRNASer) evolved to have a distinct common trajectory for discrimination by LeuRS-IA and SerRS-IIA.

- The trajectory of the type II V arm is determined by the number of unpaired bases with 5′ of the Levitt base (in Archaea, two unpaired bases for tRNALeu and one unpaired base for tRNASer).

- Because there are five tRNALeu and four tRNASer in Archaea, the different anticodons cannot be utilized for LeuRS-IA and SerRS-IIA recognition, and the type II V arm is utilized instead.

- The recognition of the type II V arm by cognate AARS enzymes has an impact on the evolution of the genetic code and the divergence of Archaea and Bacteria.

Abstract

The three 31 nucleotide minihelix tRNA evolution theorem describes the evolution of type I and type II tRNAs to the last nucleotide. In databases, type I and type II tRNA V loops (V for variable) were improperly aligned, but alignment based on the theorem is accurate. Type II tRNA V arms were a 3′-acceptor stem (initially CCGCCGC) ligated to a 5′-acceptor stem (initially GCGGCGG). The type II V arm evolved to form a stem–loop–stem. In Archaea, tRNALeu and tRNASer are type II. In Bacteria, tRNALeu, tRNASer, and tRNATyr are type II. The trajectory of the type II V arm is determined by the number of unpaired bases just 5′ of the Levitt base (Vmax). For Archaea, tRNALeu has two unpaired bases, and tRNASer has one unpaired base. For Bacteria, tRNATyr has two unpaired bases, tRNALeu has one unpaired base, and tRNASer has zero unpaired bases. Thus, the number of synonymous type II tRNA sets is limited by the possible trajectory set points of the arm. From the analysis of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase structures, contacts to type II V arms appear to adjust allosteric tension communicated primarily via tRNA to aminoacylating and editing active sites. To enhance allostery, it appears that type II V arm end loop contacts may tend to evolve to V arm stem contacts.

1. Introduction

Because of high sequence conservation, tRNAs in living organisms are a molecular fossil of the pre-life to life transition on Earth [1,2,3,4]. Tracking the evolution of tRNAomes (all the tRNAs of an organism) provides insight into the diversification of life from LUCA (the last universal common (cellular) ancestor). A clear story of the great divergence of Archaea and Bacteria can be inferred from the analysis of tRNAomes in living organisms. The reason that tRNAomes can be analyzed in such detail is that tRNA evolved during pre-life by an orderly process from RNA repeats and inverted repeats of a known sequence. The pre-life tRNA sequence remains apparent, and the diversification of tRNAome sequences can be tracked from the origin of the first tRNAs. Embedded in the tRNA sequence is a history of two overlapping pre-life worlds: (1) the polymer world; and (2) minihelix world. Since LUCA, organisms have lived in the tRNA world for ~4 billion years. Remarkably, the history of the pre-life to life transition was recorded in tRNA sequences and conserved until the present day. A view centered on tRNA and the tRNA anticodon is key to understand genetic coding [5,6,7].

The purpose of this review is to integrate an understanding of type II tRNA variable (V) loops into an appreciation of tRNA evolution, tRNAome diversification, aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (AARS) divergence, and genetic code evolution. Type I and type II tRNAs were generated from defined sequences in pre-life (Figure 1). The 93 nt tRNA precursor was generated from the ligation of three 31 nt minihelices with two distinct 17 nt cores [1]. A D loop 31 nt minihelix was ligated to two anticodon/T stem–loop–stem minihelices. A D loop minihelix also forms a stem–loop–stem, but one that is not preserved in the tRNA fold. The 31 nt minihelices were part of a more ancient translation system that attached 3′-ACCA-Gly to synthesize polyglycine, a component of protocells. During pre-life, RNAs were ligated (i.e., by a ribozyme ligase), replicated, and processed to generate, for instance, 31 nt minihelices or, sometimes, more complex molecules such as type I and type II tRNAs. As shown in Figure 1, type II tRNAs were generated from a 93 nt tRNA precursor molecule by a single internal 9 nt deletion, within ligated 3′- and 5′-acceptor stems (93 nt neglects 3′-ACCA; a primitive adapter molecule). Type I tRNAs were generated by two closely related internal 9 nt deletions. The more 5′- 9 nt deletion was identical for type I and type II tRNAs. The more 3′- 9 nt deletion, unique to type I tRNAs, was within the V loop region. Please note that the 5′- and 3′- 9 nt deletions are identical on complementary strands. Longer type II V loops, therefore, are not an expansion from a shorter type I V loop. Rather, in the evolution of the first tRNAs, type I V loops resulted from processing of a type II V loop. The processing event within the V loop region to convert a type II tRNA into a type I tRNA was a single 9 nt internal deletion within ligated 3′- and 5′-acceptor stems.

Figure 1.

Generation of type II and type I tRNAs during pre-life ~4 billion years ago. Colors reflect the three 31 nt minihelix tRNA evolution theorem [1]. Anticodon (Ac) and T stem–loop–stem (SLS) minihelices are assumed to be initially identical. “As” indicates acceptor stem. / in the sequence indicates a U-turn. After LUCA, the dominant sequence of the T loop was UU/CAAAU, as indicated. ??? indicates sequence ambiguity.

The three 31 nt minihelix tRNA evolution theorem fully describes the origin of type I and type II tRNAs [1,2,3,4,8,9]. Because type I and type II tRNAs first evolved ~4 billion years ago, this is a remarkable observation. The pre-life sequences of tRNAs and tRNA precursor molecules, however, are known with essential certainty because these sequences are ordered and conserved in living organisms. Type I and type II tRNAs evolved from RNA repeats and inverted repeats, allowing the pre-life sequence to be determined. As shown in Figure 1, the evolution of tRNA was from a 93 nt precursor molecule formed by the ligation of three 31 nt minihelices. The D loop 31 nt minihelix had the sequence GCGGCGG_UAGCCUAGCCUAGCCUA_CCGCCGC. The anticodon and T loop 31 nt minihelices had the sequence GCGGCGG_CCGGG_CU/???AA_CCCGG_CCGCCGC (_ delineates acceptor stems and stem–loop–stems; / indicates a U-turn; ? indicates sequence ambiguity).

Type II variable (V) loops of tRNAs have been misrepresented, and type I and type II tRNA V loops have been improperly aligned in tRNA databases [10,11,12,13]. Here, we describe (1) the origin of type II V loops; (2) their proper alignment to type I V loops; and (3) their interactions with cognate AARS enzymes. We posit that type II V arms are important for allosteric communication with aminoacylating and editing active sites of cognate AARS.

As noted, the type I V loop was processed from the type II V loop by an internal 9 nt deletion (Figure 1). The initial type I V loop sequence was 5 nt in length (CCGCC; a fragment of a 3′-acceptor stem). The initial type II V loop sequence was 14 nt in length (CCGCCGC_GCGGCGG). The type II V loop arose from a 3′-acceptor stem (CCGCCGC) ligated to a 5′-acceptor stem (GCGGCGG). In type II tRNAs, the type II V loop evolved to a stem–loop–stem. In a domain (i.e., Archaea or Bacteria), type II V arms for a set of synonymous tRNAs have distinct trajectories (up to three) from the tRNA, allowing for distinct recognition (i.e., by a cognate AARS). The requirement for maintaining distinct trajectories of type II V loops limits the number of synonymous type II V loop tRNA sets in an organism or domain (two in Archaea; three in Bacteria).

For translation functions, Archaea appear older than Bacteria and closer to LUCA. We posit that Bacteria diverged from Archaea very early after LUCA [14]. After a significant time of separation, Bacteria assumed their new and distinct identity. Archaeal tRNAomes are more highly ordered and simpler than bacterial tRNAomes [1,2,3,4,15]. The archaeal genetic code, furthermore, is simpler and more ordered than the bacterial code [16]. The analysis of type II V loops, type II tRNAs, and cognate AARS provides further insight into the divergence of Archaea and Bacteria.

The type II V arm interacts with AARS enzymes as a determinant for cognate AARS and as an anti-determinant for non-cognate AARS [5,6,7,16]. Leucine and serine may have entered the evolving genetic code at about the same time, and both leucine and serine utilize type II tRNAs. Leucine, serine, and arginine occupy six codon sectors within the code. LeuRS-IA, SerRS-IIA, and AlaRS-IID lack anticodon loop recognition. During code evolution, serine jumped between column 2 and column 4, and serine is the only amino acid that occupies separate columns of the code. It is likely that serine jumping between columns required tRNASer to be a type II tRNA and, also, jumping required SerRS-IIA lacking anticodon loop recognition. Because serine can be converted to cysteine by tRNA-linked chemistry [17,18,19], we posit that serine jumping during code evolution may have related to initial cysteine incorporation into the code.

Knowledge remains incomplete about allostery in cognate AARS charging of tRNAs [20,21]. It appears to us that, at least in some cases, the recognition of tRNA determinants by AARS may generate allosteric communication largely via the tRNA (i.e., acting similarly to a coiled spring) to the tRNA 3′-end for cognate tRNA aminoacylation. For many type I tRNAs and their AARS, allostery is largely initiated through accurate anticodon recognition to position the tRNA 3′-end for aminoacylation. Because LeuRS-IA and SerRS-IIA lack anticodon recognition and because tRNALeu and tRNASer have protruding type II V arms, type II V arms assumed an enhanced role to tune allosteric communication. Because LeuRS-IA has separate aminoacylating and proofreading/editing active sites, allostery, mediated through different contacts of the V arm, helps direct the tRNALeu 3′-end to switch between aminoacylating and editing active sites. In Bacteria but not Archaea, tRNATyr is a type II tRNA, and tRNATyr type II V arm contacts help direct accurate tRNATyr charging in Bacteria.

2. Type I and Type II tRNA V Loops

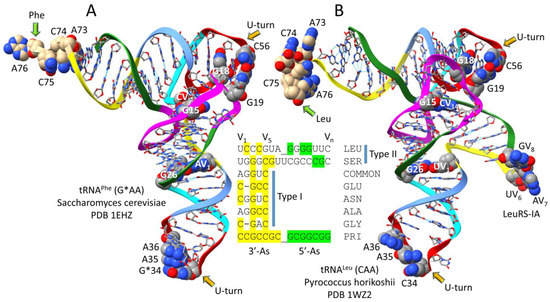

Figure 2 shows type I and type II tRNAs and proper alignments of V loops. The initial type I V loop sequence was CCGCC. The initial type II V loop sequence was CCGCCGC_GCGGCGG, derived from the ligation of a 3′-acceptor stem (CCGCCGC) to a 5′-acceptor stem (GCGGCGG) (Figure 1) [1]. Coloring of the tRNAs is according to the three 31 nt tRNA evolution theorem that completely describes the evolution of type I and type II tRNAs [1]. Colors in common indicate homologous sequences that were identical sequences in pre-life. In existing tRNA databases [12,13,22], type I and type II V loops were improperly aligned to one another because the three 31 nt minihelix tRNA evolution theorem was not applied.

Figure 2.

The comparison of type I and type II tRNAs and proper alignment of V loops. (A) A type I tRNAPhe from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (a Eukaryote) [23]. (B) A type II tRNALeu from Pyrococcus horikoshii (an ancient Archaeon) [24]. Colors reflect the three 31 nt tRNA evolution theorem: (green) 5′-acceptor stems and 5′-acceptor stem remnants; (magenta) D loop; (cyan–red–cornflower blue) anticodon and T stem–loop–stems; and (yellow) 3′-acceptor stems and 3′-acceptor stem remnants. In the images, some bases are emphasized using space-filling representation. ChimeraX 1.6.1 was used for molecular graphics [25,26,27]. Alignment of some type I and type II V loops from Pyrococcus furiosus is based on the theorem. PRI indicates the tRNAPri type II V loop (PRI for primordial; the initial pre-life sequence). COMMON indicates the most common P. furiosus type I V loop sequence. G*34 indicates 2′-O-methyl G. Atom colors: (C) gray or beige; (N) blue; (O) red.

3. Different Trajectories of the Type II tRNA V Arms

A gallery of type II tRNAs is shown in Figure 3, emphasizing the contacts and trajectories of the V arms. The type II tRNAPri V arm is self-complementary along its entire length and can form many different or tangled G=C pairings. Type II V arms, therefore, evolved to form stem–loop–stems that could be discriminated by a cognate AARS. We find that the trajectory of the V arm depends on the number of unpaired bases just 5′ to the Levitt base pair (2, 1, or 0; sometimes −1). The Levitt base pair is a reverse Watson–Crick pair between tRNA base 15 and Vn (for a V loop of n bases (numbered V1–Vn)). A reverse Watson–Crick base pair is a standard Watson–Crick pair, as in DNA, with one of the bases flipped over and slightly shifted.

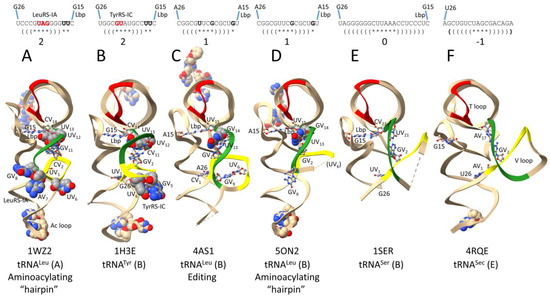

Figure 3.

Distinct trajectories of type II V arms depend on the number of unpaired bases just 5′ of the Levitt base Vn (2, 1, 0, or −1). (A) Archaeal (A for archaeal) tRNALeu in the aminoacylating “hairpin” conformation [24,28]. (B) Bacterial (B for bacterial) tRNATyr [29]. (C) Bacterial tRNALeu in the editing/proofreading conformation [30]. (D) Bacterial tRNALeu in the aminoacylating “hairpin” conformation [31]. (E) Bacterial tRNASer [32]. (F) Human (E for Eukarya) tRNASec (Sec for selenocysteine) [33]. Colors: (red) T loop; (yellow) 1st 7 nt of the V loop; and (green) last 7 nt of the V loop. Space-filling and ball and stick bases are shown for emphasis. Parentheses indicate stems; * indicates a loop. Lbp indicates the Levitt base pair. See the text for details.

Figure 3A shows archaeal Pyrococcus horikoshii tRNALeu (CAA) in the aminoacylating “hairpin” conformation [24,28]. Structures of tRNAs are from co-crystal structures with cognate AARS. “Hairpin” relates to the bent-down 3′-end of the tRNALeu into the LeuRS-IA aminoacylating active site. V loops are numbered V1-Vn for a V loop of n bases. For historical reasons, standard numbering of tRNAs breaks down in the D loop and V loop, explaining why we use the V1 to Vn numbering here. P. horikoshii (an ancient Archaeon) tRNALeu (CAA) has a V loop of 14 nt, which is the primordial (pre-life) length [1,2,3]. UV1 interacts with tRNA-G26 (UV1~G26). V2-CCC-V4 is the V arm 5′-stem. V5-GUAG-V8 is the V arm end loop. V arm end loop bases V6-UAG-V8 are highly conserved in Archaea and bind to archaeal LeuRS-IA, as indicated (see below). V9-GGG-V11 forms the V arm 3′-stem. V12-UU-V13 are two unpaired bases, just 5′ of the Levitt base (CV14). The Levitt base (CV14) forms a reverse Watson–Crick base pair with tRNA-G15 (CV14 = G15) (the Levitt base pair). The number of unpaired bases just 5′ of the Levitt base Vn determines the trajectory of the V arm from the tRNA body.

Figure 3B shows bacterial Thermus thermophilus tRNATyr (GU*A) (U* for pseudouridine) from a co-crystal with TyrRS-IC [29]. The V loop is 14 nt, which is the primordial length. UV1 interacts with tRNA-G26 (UV1~G26). The V arm 5′-stem is V2-GGC-V4. The V arm end loop is V5-GUAU-V8. V arm end loop bases V5-GU-V6, along with V5-UU-V6, are highly conserved with tRNATyr V loops of 14 nt in Bacteria, and bind to TyrRS-IC, as indicated (see below). Type II tRNATyr V loops of less than 14 nt lose the conserved V5 and V6 bases and, presumably, also V arm end loop contacts by TyrRS-IC (see below). V9-GCC-V11 form the V arm 3′-stem. V12-UU-V13 are unpaired bases just 5′ of the Levitt base (CV14) that forms the Levitt base pair with tRNA-G15 (CV14 = G15).

Figure 3C shows bacterial Escherichia coli tRNALeu (UAA) from a co-crystal with LeuRS-IA in the editing/proofreading conformation (the 3′-end of tRNALeu is in the LeuRS-IA editing/proofreading active site rather than the aminoacylating active site) [30]. The tRNALeu (UAA) V loop is 15 nt in E. coli. CV1 interacts with tRNA-A26 (CV1~A26). V2-GGCG-V5 is the V arm 5′-stem. V6-UUCG-V9 is the V arm end loop. In the editing conformation, UV6 and GV9 interact, and the V arm end loop is ordered. V10-CGCU-V13 is the V arm 3′-stem. GV14 is the single unpaired base that determines the V arm trajectory, just 5′ of UV15 that forms the Levitt reverse Watson–Crick base pair with tRNA-A15 (UV15 = A15).

Figure 3D shows the same Escherichia coli tRNALeu (UAA) from a LeuRS-IA co-crystal but in the aminoacylating hairpin conformation [31]. The major differences from the editing/proofreading conformation image in Figure 3C are as follows: (1) the conformation of the V arm 3′-stem (green) is altered; (2) the V arm end loop is disordered (Figure 3D); (3) the orientation of end loop base GV9 is changed; and (4) UV6 has lost contact to GV9 and is disordered (Figure 3D). We posit that allosteric interactions initiated by appropriate (aminoacylating) or inappropriate (editing/proofreading) contacts at the tRNALeu (UAA) 3′-end are communicated to and amplified by contacts at the V arm (see below).

Figure 3E shows bacterial Thermus thermophilus tRNASer (GGA) from a co-crystal with SerRS-IIA [32]. The tRNASer (GGA) is significantly disordered, and the structure is not in an aminoacylating conformation (the tRNASer 72-CGCCA 3′-end is disordered). The V loop is 22 nt. UV1 can probably interact with tRNA-G26 (UV1~G26) (tRNA-G26 is mostly disordered in the structure). V2-AGGGGGG-V8 is the V arm 5′-stem. The V arm end loop is V9-CUUAAA-V14 (mostly disordered). The V arm 3′-stem is V15-CCUCCCU-V21. CV22 is the Levitt base that pairs with tRNA-G15 (CV22 = G15). No unpaired bases are present just 5′ of the Levitt reverse Watson–Crick base pair (trajectory set point of 0). In Bacteria, tRNASer V arm stems are generally longer than archaeal tRNASer V arm stems. We posit that the lengthening of the stem in Bacteria may reflect a need to stabilize the V2 = V(n−1) pair. In Archaea, by contrast, the V2 = V(n−2) pair forms (in Archaea, the set point trajectory of the tRNASer V arm is 1, in contrast to 0 in Bacteria).

Figure 3F shows a somewhat unusual case that is included here mostly for completeness. Human tRNASec (UCA) is shown from a co-crystal with SerRS-IIA (Sec for selenocysteine) [33]. SerRS-IIA attaches serine to tRNASec (Ser-tRNASec), which is then converted to Sec-tRNASec by other enzymes utilizing tRNA-linked chemistry. The V loop is 17 nt. In this case, AV1 probably interacts with tRNA-U26 (AV1 = U26). V2-GCUGUC-V7 is the V arm 5′-stem. V8-UAGC-V11 is the V arm end loop. V12-GACAGA-V17 is the V arm 3′-stem. The GV2~AV17 interaction is notable. Because AV17 interacts with GV2, the Levitt base pair to tRNA-G15 cannot form.

We conclude that V arm trajectories are different with two, one, or zero unpaired bases just 5′ of the Levitt base. In the view shown in Figure 3, Figure 3A,B (trajectory score of 2; two unpaired bases just 5′ of the Levitt base) have the type II V arm extending almost straight back. Figure 3C,D (score of 1) have the V arm angling more to the right, and Figure 3E,F (scores of 0 and −1) have the V arm pointing to the right. At the time of writing, some desired images were not available. For instance, an archaeal SerRS-IIA-tRNASer structure would be informative (V loop trajectory score 1 in Archaea versus 0 in Bacteria).

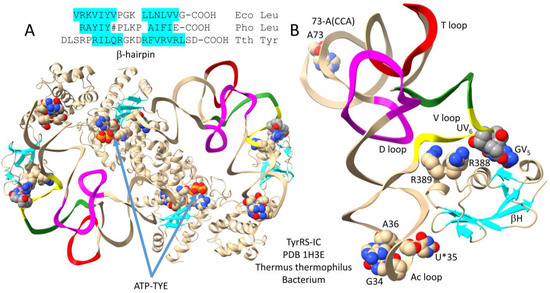

4. LeuRS-IA-tRNALeu Co-Crystal Structures

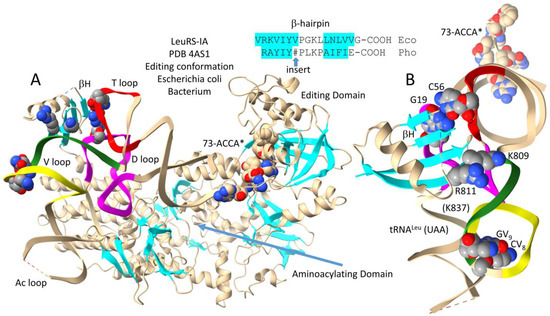

To better understand how the type II V arm is recognized, we have analyzed a number of cognate AARS-type II tRNA co-crystal structures. Figure 4 shows a co-crystal of archaeal Pyrococcus horikoshii LeuRS-IA complexed with tRNALeu (CAA) [24,28]. P. horikoshii is an ancient Archaeon with a translation system very similar to the one that must have functioned at LUCA. The tRNALeu (CAA) is in the “hairpin” conformation with the tRNA 3′-end bent down into the aminoacylating active site. We could not identify an archaeal co-crystal structure with LeuRS-IA-tRNALeu in an editing/proofreading conformation for comparison.

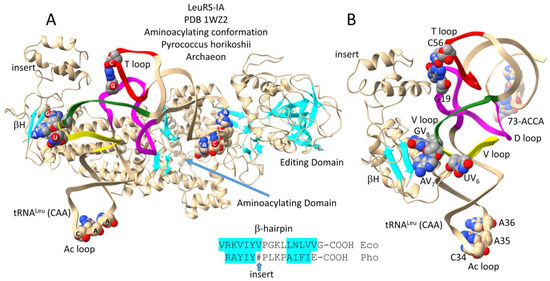

Figure 4.

Archaeal LeuRS-IA bound with tRNALeu (CAA) in the aminoacylating conformation [24,28]. (A) The entire structure. (B) A C-terminal LeuRS-IA detail emphasizing V arm end loop contacts. β-sheets are cyan. Colors: (magenta) D loop; (yellow) 1st 7 nt of the V loop; (green) last 7 nt of the V loop; and (red) T loop. The sequence of a β-hairpin (βH) at the C-terminus of Escherichia coli (Eco) and P. horikoshii (Pho) LeuRS-IA is shown. # indicates an ~93-amino-acid insert in the Pho C-terminal β-hairpin. Atom colors: (C) beige or gray; (N) blue; (O) red.

Figure 4A shows the archaeal LeuRS-IA-tRNALeu (CAA) structure in the aminoacylating conformation. LeuRS-IA has separate aminoacylating and editing/proofreading active sites. The tRNALeu (CAA) 3′-end is in the hairpin conformation for aminoacylation. Because LeuRS-IA is a class I AARS, the aminoacylating active site is also identified by parallel β-sheets. Figure 4B shows a C-terminal fragment of LeuRS-IA interacting with the tRNALeu V arm. In Archaea, the highly conserved V arm end loop sequence V6-UAG-V8 interacts with the C-terminal LeuRS-IA β-hairpin. In Pyrococcus horikoshii but not in Bacteria, the β-hairpin has an ~93-amino-acid insert that interacts with the tRNALeu elbow, where the D loop and T loop interact (i.e., where tRNA-G19 pairs with tRNA-C56 (a bent Watson–Crick pair)). The length of the insert in the archaeal C-terminal LeuRS-IA β-hairpin depends on how sequences are aligned. The V loop is 14 nt, which is the primordial (pre-life) length [1,2,3]. More detail about the tRNALeu (CAA) V loop is shown in Figure 3A. The comparison of an archaeal editing/proofreading LeuRS-IA-tRNALeu structure would enrich this discussion.

Figure 5 shows a bacterial Escherichia coli LeuRS-IA-tRNALeu (UAA) co-crystal structure in the aminoacylating hairpin conformation [30]. Figure 5A shows the intact structure. Figure 5B shows a LeuRS-IA C-terminal domain detail, highlighting interactions with the type II V loop. In contrast to archaeal LeuRS-IA (Figure 4), bacterial LeuRS-IA does not make contact to the V arm end loop (Figure 5). Furthermore, the C-terminal domain of bacterial LeuRS-IA, which lacks the ~93-amino-acid insert of archaeal LeuRS-IA, is significantly rearranged and redirected compared to the archaeal C-terminal domain. Notably, the bacterial C-terminal β-hairpin interacts with the tRNALeu elbow (i.e., the tRNA-G19 bent Watson–Crick pair with tRNA-C56). K809, R811, and R837 interact with the V arm 3′-stem (green). The V arm end loop is disordered, and V arm end loop base GV9 is flipped out of the end loop. See also Figure 3D. We posit that K809, R811, and K837 interaction with the V arm 3′-stem (green) generates allosteric communication with the tRNALeu 3′-end, particularly in the aminoacylating conformation, and that tighter attachment to the V arm 3′-stem in the aminoacylating conformation disrupts the structure of the V arm end loop.

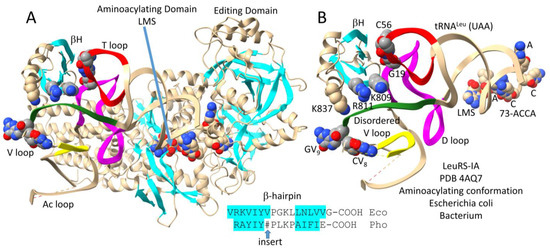

Figure 5.

The bacterial Escherichia coli LeuRS-IA-tRNALeu (UAA) co-crystal structure in the aminoacylating hairpin conformation [30]. (A) the full structure; (B) a C-terminal LeuRS-IA detail emphasizing V arm 3′-stem contacts and the conformation of the V loop. LMS is a non-reactive leucine–AMP reaction intermediate analog. βH indicates the C-terminal LeuRS-IA β-hairpin. See the text for details. Colors as in other figures. Dotted lines indicate unresolved structure.

Figure 6 shows bacterial Escherichia coli LeuRS-IA-tRNALeu (UAA) in the editing/proofreading conformation [30]. The tRNALeu 3′-end, which was chemically modified, locates to the editing active site. Figure 6A shows the entire structure. Figure 6B highlights C-terminal LeuRS-IA-tRNALeu V arm contacts, which are significantly altered from the aminoacylating conformation (Figure 5). The C-terminal β-hairpin maintains its contact to the tRNA-G19 = tRNA-C56 pair at the tRNALeu elbow. K809 and R811 move away from the tRNALeu V arm 3′-stem. K837 that is visualized in the aminoacylating conformation (Figure 5) is unstructured in the editing/proofreading conformation (Figure 6). Because of weakened contacts to the V arm 3′-stem in the editing conformation, the tRNALeu V arm end loop is structured. GV9 stacks on CV8 and interacts with UV6 (see Figure 3C; compare to Figure 5). We posit that distal tRNALeu V arm and elbow determinant contacts act as allosteric effectors to influence accurate tRNA charging and editing. Allosteric communication is transmitted back and forth from the tRNALeu 3′-end and the type II V arm, such that contacts to the V arm amplify allostery initiated by tRNALeu 3′-end contacts. It is much more difficult to imagine strong allosteric communication being transmitted through the LeuRS-IA protein structure. For instance, the protein connection of the C-terminal LeuRS-IA domain to the aminoacylating active site is very flexible (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Bacterial Escherichia coli LeuRS-IA bound to tRNALeu (UAA) in the editing/proofreading conformation [30]. (A) The full structure; (B) C-terminal LeuRS-IA-tRNALeu contacts emphasizing elbow and weakened V arm 3′-stem contacts (compare to Figure 5). A* indicates a modified 3′-A76 base that directs the tRNALeu 3′-end into the editing/proofreading active site. Colors as in previous figures.

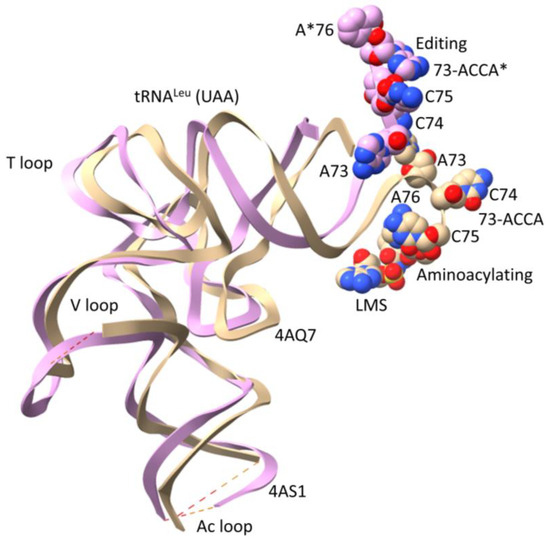

Figure 7 shows an overlay of Escherichia coli tRNALeu (UAA) in the aminoacylating and editing/proofreading conformations to indicate possible allosteric communication [21,30]. Structures were aligned based on LeuRS-IA protein. Because leucine occupies a 6-codon box in the genetic code, LeuRS-IA makes no contacts with the tRNALeu anticodon loop. Instead, allosteric communication is established between the tRNALeu V arm and the 3′-end, reinforcing the appropriate 3′-end placement into the aminoacylating or the editing/proofreading active site.

Figure 7.

Overlay of LeuRS-IA-tRNALeu (UAA) co-crystal structures indicates allosteric communication linking the tRNALeu 3′-end and the type II V arm 3′-stem [30]. The beige tRNALeu is in the aminoacylating hairpin conformation, with an unstructured V arm end loop (see Figure 5). LMS is a non-reactive leucine–AMP reaction intermediate analog bound in the aminoacylating active site. The pink tRNALeu is in the editing/proofreading conformation, with a structured V arm end loop (see Figure 6). A*76 indicates a modified 3′-A* that directed the tRNALeu 3′-end into the editing/proofreading active site.

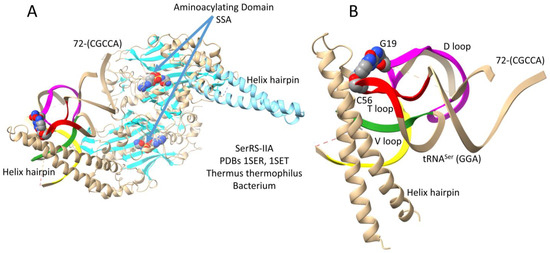

5. SerRS-IIA-tRNASer and -tRNASec Co-Crystal Structures

Figure 8 shows a bacterial Thermus thermophilus SerRS-IIA-tRNASer co-crystal structure [32,34]. As do most or all class II AARSs, SerRS-IIA functions as an α2-dimer. Serine is in a 6-codon box in the genetic code. Consistent with a 6-codon box, SerRS-IIA lacks tRNASer anticodon recognition. Figure 8A is the entire structure (1SER) supplemented with a light blue N-terminal helix hairpin and an SSA non-reactive reaction intermediate analog from 1SET. Figure 8B highlights SerRS-IIA-tRNASer type II V arm contacts. An N-terminal helix hairpin forms a brace that contacts the tRNA elbow (tRNA-G19 = tRNA-C56) (magenta and red), the V arm 3′-stem (yellow), and the V arm 5′-stem (green). Perhaps because only a single tRNASer is bound, the N-terminal helix hairpin from the other α subunit was not visualized in the 1SER structure. The tRNASer 3′-end 72-CGCCA is disordered, so the structure does not fully reflect an aminoacylating conformation. Perhaps the reaction must proceed to the serine–AMP stage to more stably attract the tRNASer 3′-end. The tRNASer structure shows a significant amount of disorder, possibly indicating allosteric communication linking the V arm and 3′-end contacts. The mode of SerRS-IIA-tRNASer binding may have facilitated serine jumping from column 2 to column 4 of the genetic code. Serine is the only amino acid to have split between two genetic code columns. The binding of only a single tRNASer by SerRS-IIA appears to indicate negative cooperativity in tRNASer binding.

Figure 8.

A Thermus thermophilus SerRS-IIA-tRNASer (GGA) co-crystal structure [32,34]. The SerRS-IIA active site is formed on a surface of antiparallel β-sheets. (A) The entire structure. The structure shown is a composite of the 1SER (beige) and 1SET (light blue; SSA) structures. (B) A detail that highlights V arm stem contacts. Colors as in other figures.

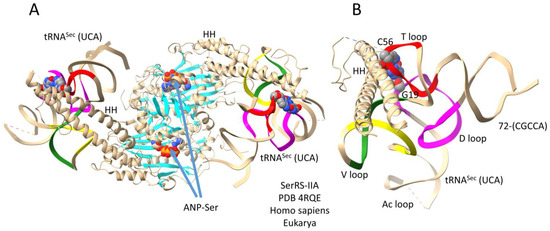

Figure 9 shows a human SerRS-IIA-tRNASec (UCA) co-crystal structure [33]. Because not all organisms encode selenocysteine (Sec), this is somewhat of an unusual case. Anticodon UCA represents stop codon UGA. The structure is important for the current discussion partly because it helps clarify some aspects of the structure shown in Figure 8. In Figure 9A, two tRNASec (UCA) are bound, so both N-terminal helix hairpins are observed, possibly rendering the structure more intuitive to interpret (compare to Figure 8). The aminoacylating active site is identified by (1) a surface of antiparallel β-sheets; (2) ANP binding (ANP is a non-reactive ATP analog); and (3) serine binding. Because the tRNASec 3′-end (72-CGCCA) is disordered, the structure does not fully reflect an aminoacylating conformation. The tRNASec (UCA) has a somewhat unusual V loop structure with a broken Levitt pair and a GV2 = AV17 interaction (Figure 3F). The altered tRNASec (UCA) type II V arm trajectory (score of −1 (tRNASec) versus score of 0 (tRNASer)) may aid in specifying subsequent tRNA-linked chemistry to convert Ser-tRNASec to Sec-tRNASec and to not improperly convert Ser-tRNASer to Sec-tRNASer. It appears that negative cooperativity observed in SerRS-IIA-tRNASer binding (Figure 8) is relieved in SerRS-IIA-tRNASec binding (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

A human SerRS-IIA-tRNASec (UCA) co-crystal structure [33]. (A) The entire structure; (B) an image highlighting tRNASec (UCA) V arm stem and elbow contacts. ANP is a non-reactive ATP analog. HH indicates a helix hairpin. Colors as in other figures.

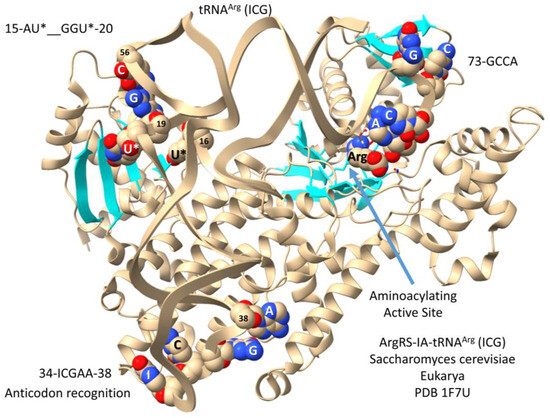

6. ArgRS-IA-tRNAArg

This section is included for completeness and to tie the analysis of type II tRNAs into the formation of 6-codon genetic code sectors. Leucine, serine, and arginine probably entered the genetic code at about the same time and occupied 6-codon sectors [5,6,7]. In contrast to LeuRS-IA and SerRS-IIA, ArgRS-IA utilizes a type I tRNA and, also, anticodon recognition for tRNAArg (Figure 10). Because ArgRS-IA utilizes five tRNAArg anticodons from two genetic code rows (2 and 3), there is potential ambiguity in reading the anticodon sequence. The structure shown is a yeast ArgRS-IA-tRNAArg (ICG) (I for inosine). Inosine is formed by the deamination of adenine. In Archaea, wobble tRNA-34A is not utilized. Notably, when A is modified to I in Bacteria and Eukarya, the corresponding G anticodon (i.e., GCG) is not utilized. Because tRNA-34I reads mRNA wobble A, C, and U, wobble inosine can only be utilized in a 3- or 4-codon sector [35,36]. The structure in Figure 10 has tRNAArg (ICG) in the hairpin conformation with the tRNAArg 73-GCCA bending down into the aminoacylating active site, which is also identified by parallel β-sheets and arginine binding. The anticodon loop has the sequence 34-ICGAA-38 [37]. Because of ambiguities in tRNAArg anticodon reading, the anticodon loop is substantially unwound, exposing tRNA-38A to interact with ArgRS-IA. Because of anticodon ambiguity, the strongest sequence-specific contacts are expected for tRNA-35C and tRNA-38A. Substantial unwinding of the anticodon loop is expected to generate torque on the tRNAArg 3′-end to support the aminoacylating conformation.

Figure 10.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae ArgRS-IA-tRNAArg (ICG) [37]. U* for 5,6-dihydrouridine. This is a very good structure for molecular dynamics studies, for instance, to demonstrate the tRNA anticodon and elbow to 3′-GCCA allostery.

Numbering in the tRNA D loop is confusing, because, for historical reasons, numbering was based on eukaryotic tRNAs with three deleted D loop nts. The D loop evolved from a 17-nucleotide UAGCC repeat (i.e., D1-UAGCCUAGCCUAGCCUA-D17) (Figure 1) [1,2]. According to improved numbering, 15-AU*--GGU*-20 would be numbered D8-AU*--GGU*-D14 (with two deleted nts (D10 and D11)). The tRNAArg (ICG) elbow (G19 = C56) and modified bases in the D loop make contact to ArgRS-IA, as shown.

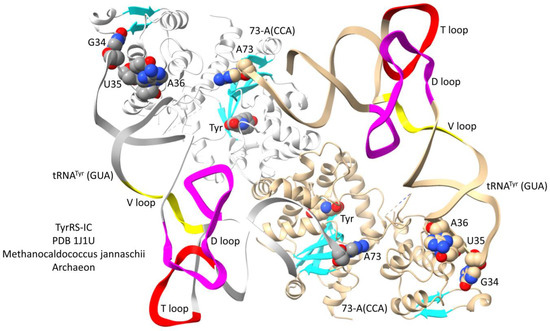

7. TyrRS-IC-tRNATyr (GUA) in Archaea and Bacteria

Interestingly, tRNATyr is a type I tRNA in Archaea and a type II tRNA with a longer V arm in Bacteria [38]. An archaeal TyrRS-IC-tRNATyr co-crystal is shown in Figure 11. In contrast to most other class I AARSs, which are monomers, class IC AARSs are obligate α2-dimers with anticodon-binding domains and aminoacylating domains in opposite subunits. Via TyrRS-IC protein, the anticodon-interaction domain is only loosely connected to the aminoacylating domain, indicating that allosteric contacts at the anticodon-binding region may be communicated to the aminoacylating active site mostly via the tRNA. Because the tRNATyr (GUA) 3′-end is disordered (only A73 of 73-ACCA is ordered), the structure is not in a fully aminoacylating conformation. The aminoacylating active site is indicated by binding of tyrosine and parallel β-sheets.

Figure 11.

Archaeal TyrRS-IA bound to type I tRNATyr (GUA) [38]. Colors as in other figures. One α subunit and tRNATyr are white.

In Bacteria, tRNATyr is a type II tRNA with a longer V loop [29]. In the ancient Bacterium Thermus thermophilus, tRNATyr has a type II V loop of 14 nt, the primordial length. A co-crystal structure of T. thermophilus TyrRS-IC bound to tRNATyr is shown in Figure 12. Figure 12A shows the entire structure. Figure 12B shows more detailed contacts by a C-terminal TyrRS-IC fragment to the tRNATyr V arm 5′-stem and end loop. The aminoacylating active site is identified by (1) parallel β-sheets; (2) ATP binding; and (3) TYE (a non-reactive tyrosine analog) binding. Because tRNATyr 74-CCA is unstructured, the image does not fully represent an aminoacylating conformation. The type II V arm is contacted by TyrRS-IC R388 and R389 on its 5′-stem (yellow). V arm end loop bases V5-GU-V6 bind TyrRS-IC. The TyrRS-IC C-terminal domain is loosely tethered to the anticodon-binding domain, which is loosely tethered to the aminoacylating domain. From the image, it appears that allosteric effects from tRNATyr anticodon and V arm 5′-stem contacts may be mostly communicated to the tRNATyr 3′-end via tRNATyr more than through the TyrRS-IC protein. The protein linkage of the C-terminal TyrRS-IC domain with the aminoacylating active site is very flexible, and the most relevant communication would be with the aminoacylating active site in the opposite α subunit.

Figure 12.

Bacterial TyrRS-IC bound to type II tRNATyr (GU*A) (U* for pseudouridine) [29]. (A) The entire structure; (B) the C-terminal TyrRS-IC domain bound to tRNATyr (GU*A). The aminoacylating active site binds ATP and TYE (a non-reactive tyrosine analog). A β-hairpin at the Thermus thermophilus (Tth) TyrRS-IC C-terminus may relate to C-terminal β-hairpins in Escherichia coli (Eco) and Pyrococcus horikoshii (Pho) LeuRS-IA. # indicates an ~93-amino-acid insert in the Pho C-terminal β-hairpin sequence. Colors are consistent with other figures.

Comparing the archaeal and bacterial TyrRS-IC-tRNATyr (GUA) structures, archaeal TyrRS-IC lacks the C-terminal domain that binds the bacterial tRNATyr type II V arm. Because the archaeal TyrRS-IC enzyme recognizes a type I tRNATyr, absence of the type II V arm-binding domain in archaeal TyrRS-IC is as expected. Either the bacterial TyrRS-IC C-terminal domain was a bacterial addition or an archaeal deletion. We posit, however, that the TyrRS-IC C-terminal domain in Bacteria may be distantly homologous to the LeuRS-IA C-terminus because of the possible similarities of the C-terminal β-hairpins. If this idea is correct, archaeal and bacterial TyrRS-IC may have diverged very early in evolution (i.e., at LUCA), and archaeal TyrRS-IC may have subsequently deleted the C-terminal domain. It appears to us that divergence of archaeal and bacterial TyrRS-IC may have occurred very early in evolution at the time that type I and type II tRNAs were first sorted. Because Thermus thermophilus tRNATyr has a 14 nt V loop, which is the primordial length, this observation is also consistent with early sorting and divergence of type I and type II tRNAs.

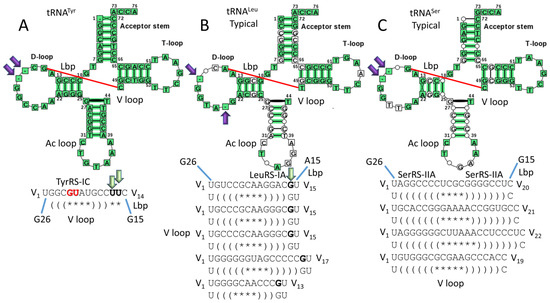

8. Type II V Loops in an Ancient Bacterium

Figure 13 compares type II V loops for Thermus thermophilus [13]. In Archaea, tRNALeu and tRNASer are type II tRNAs with V arm trajectory set points of 2 and 1, respectively. In Bacteria, tRNATyr, tRNALeu, and tRNASer are type II tRNAs with V arm trajectory set points of 2, 1, and 0, respectively. We consider T. thermophilus to be a reasonable reference organism for the earliest recognizable divergence of Archaea and Bacteria.

Figure 13.

Type II V loops in Thermus thermophilus (typical tDNA sequences are shown) [13]. (A) tRNATyr; (B) tRNALeu; and (C) tRNASer. Lbp indicates the Levitt base pair. Deleted bases in the D loop are indicated with purple arrows. Green arrows indicate unpaired bases just 5′ of the Levitt base that determine the trajectory set point of the V arm from the tRNA body (Figure 3). Notations are consistent with other figures. TyrRS-IC binds the V arm 5′-stem and V arm end loop bases V5-GU-V6 (red; see Figure 12). LeuRS-IA binds the V arm 3′-stem but not the end loop (Figure 5 and Figure 6). SerRS-IIA binds the elbow and the V arm 5′- and 3′-stems (Figure 8 and Figure 9).

Figure 13A represents tRNATyr (trajectory set point 2). Figure 13B represents a typical tRNA for tRNALeu (set point 1). Figure 13C represents a typical tRNA for tRNASer (set point 0). Typical tRNAs represent a consensus tRNA with relaxed scoring [13]. The program used to generate the cloverleaf diagrams does not handle V loop sequences appropriately, so the relevant V loop sequences are shown individually. For all type II tRNAs in T. thermophilus, UV1 forms a wobble pair with tRNA-G26, as in Archaea. Only TyrRS-IC interacts with V arm end loop bases (V5-GU-V6 in Tth). TyrRS-IC contacts are also made to the V arm 5′-stem (Figure 12). LeuRS-IA interacts with the V arm 3′-stem, making stronger contacts to the stem in the aminoacylating conformation compared to the editing/proofreading conformation (compare Figure 5 and Figure 6). SerRS-IIA interacts with both the V arm 5′- and 3′-stems. In Bacteria, the tRNASer V arm set point of 0 may correlate with the longer lengths of the tRNASer V arm stems compared to Archaea. Longer tRNASer stems in Bacteria may be necessary to maintain V2-V(n−1) pairing. Also, the longer tRNASer V arm stems may otherwise help accurately discriminate three type II tRNAs in Bacteria compared to two type II tRNAs in Archaea.

Because the tRNATyr V loop is 14 nt, which is the primordial length, type II tRNATyr in Bacteria may be as ancient as a time when most type II V loops were 14 nt in length. It appears to us that bacterial type II tRNATyr may have evolved from an ancient type II tRNASer before the expansion of the tRNASer V arm [4]. In T. thermophilus, tRNATyr and tRNASer are similar tRNAs. The deleted bases in the D loop are the same, the Levitt base pair is the same, and the T loops are the same. By contrast, tRNALeu has a different deleted base in the D loop, a different Levitt base pair, and a different T loop base (tRNA-57A versus tRNA-57G). We posit that, in Bacteria, type II tRNATyr may have evolved from an ancient tRNASer with a 14 nt V loop.

9. Missing Data

In this manuscript, we have attempted to assemble a coherent story for the evolution and divergence of type II V loops in Archaea and Bacteria based on the evolution of type I and type II tRNAs. We have previously shown that tRNAomes for Archaea are simpler than for Bacteria and closer to LUCA [4]. This comparison holds for type II V loops. To improve the current analyses, additional data will be useful. Many AARS-tRNA structures should be created or modeled using native, modified tRNAs. Because modeling does not generally support chemistry, simulations can be performed with modified tRNAs and reactive intermediates. Structures should be created using cryo-electron microscopy and natural tRNAs. Perhaps, structures could be modeled using AlphaFold 3 [39]. Also, molecular dynamics simulations and analyses of AARS-tRNA allostery should be performed. We were surprised not to find more of such papers. For instance, LeuRS-IA switching between aminoacylating and editing/proofreading modes could be analyzed by simulation. In Archaea, observing a LeuRS-IA-tRNALeu structure in the editing/proofreading conformation would be useful. In Archaea, observing a SerRS-IIA-tRNASer structure (V arm trajectory set point of 1 in Archaea versus 0 in Bacteria) would add to the current discussion. In Bacteria, an Escherichia coli TyrRS-IC-tRNATyr structure would be of interest. The molecular dynamics simulation of the ArgRS-IA-tRNAArg (ICG) structure (Figure 10) should provide insight into allostery involving distal AARS-tRNA determinants (anticodon loop and elbow).

10. Allostery

We posit that allosteric communication between distal tRNA contacts (determinants) and the tRNA 3′-end may be important for the accurate aminoacylation of cognate tRNAs [20,21]. Several simulations have been performed on AARS enzymes, but few appear to address the issue of allostery linking distal tRNA determinants (i.e., anticodon loop, elbow, and V arm) and the tRNA 3′-end. A study of MetRS-IA-tRNAMet indicates that most allosteric communication in this AARS is through the MetRS-IA protein, not the tRNAMet [40]. In MetRS-IA, however, the protein is well connected, extending from the anticodon-binding to the tRNAMet 3′-end. For some other AARS enzymes, distal cognate tRNA determinants appear to be loosely tethered through the protein to the aminoacylating active site and the tRNA 3′-end. For instances, see LeuRS-IA-tRNALeu (Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6) and TyrRS-IC-tRNATyr (Figure 11 and Figure 12). Most simulations to date appear to best describe events at the aminoacylating or editing/proofreading active sites [41,42,43,44,45,46]. We posit that, for some AARS, events at the tRNA 3′-end may be coupled to distal tRNA determinants primarily through the tRNA, acting in similar fashion to a coiled spring. We suggest this type of allosteric communication for LeuRS-IA-tRNALeu and TyrRS-IC-tRNATyr. In such a case, events at the aminoacylating or editing active sites would be amplified by distal tRNA determinant contacts. For instance, the C-terminal domain of bacterial LeuRS-IA makes distinct tRNALeu V arm 3′-stem contacts in the aminoacylating and editing/proofreading conformations (compare Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7).

11. Divergence of Archaea and Bacteria

The evolution of type II tRNA V arms appears to relay a simple story about divergence of the archaeal and bacterial domains. We support the following model. From LUCA, Archaea and Bacteria diverged. For translation functions, Archaea are most similar to LUCA, and Bacteria are more distinct. Bacteria appear to have assumed their separate identity after significant isolation from Archaea. For instance, no intermediate organisms separating Archaea and Bacteria have been identified. Bacteria partly diverged because of their different transcription system. Bacteria rely on the coevolution of sigma factors, bacterial promoters, and a streamlined RNA polymerase [14,47,48]. For translation functions, Bacteria appear more diverged from LUCA than Archaea. Bacterial divergence is evident by the inspection of tRNAomes and the genetic code. In many ways, Bacteria appear to be a more successful and innovated prokaryote compared to Archaea.

Table 1 summarizes type II V arm trajectory scores and lengths in Pyrococcus furiosus (an ancient Archaeon) and Thermus thermophilus (an ancient Bacterium) [13]. In P. furiosus, tRNATyr (1 tRNATyr) is a type I tRNA (5 nt V loop). In P. furiosus, tRNALeu is a type II tRNA with a trajectory score of 2 and a length of 14 nt (5 tRNALeu), the primordial length. Also, tRNASer has a trajectory score of 1 and a length of 15 nt (4 tRNASer). In T. thermophilus, tRNATyr has a score of 2 and a length of 14 nt, the primordial length (1 tRNATyr). Also, tRNALeu has a score of 1 and lengths of 13–17 nt (5 tRNALeu), and tRNASer has a score of 0 and lengths of 19–22 nt (4 tRNASer). It appears to us that, within a domain, collections of synonymous tRNAs with type II V loops must have different trajectory set point scores and, thus, distinct trajectories of V arms from the tRNA body (Figure 3). Archaeal type II V arms for tRNALeu are generally shorter compared to bacterial V arms. In Archaea, tRNATyr was sorted to become a type I tRNA (closely related to tRNAAsn) [4]. Because Archaea only utilize type II tRNAs encoding leucine and serine, there was little pressure to lengthen V arms, and tRNALeu and tRNASer generally maintained shorter V arms in Archaea than in Bacteria. Because type II tRNATyr (score of 2; Vn of 14 nt) was adopted in Bacteria, tRNALeu was downgraded to a trajectory score of 1 (i.e., Vn of 13–17 nt in T. thermophilus), and tRNASer was downgraded to a score of 0 (Vn of 19–22 nt in T. thermophilus), relative to Archaea. In Bacteria, we posit that longer tRNASer V arm stems may have evolved to stabilize the V2 = V(n−1) pairing. Because of the different V arm set point in Archaea, V2 = V(n−2) pairing is utilized. In order to sort three type II tRNA amino acids in Bacteria, tRNATyr is generally 14 nt or shorter. The primordial length is 14 nt. Interestingly, the tRNATyr V loop is 13 nt in Escherichia coli and the V arm end loop sequence of V5-GU-V6 that binds TyrRS-IC in T. thermophilus (or V5-UU-V6 in some Bacteria) is not present. We posit that, in E. coli, contact to the V arm end loop is not utilized, and only contacts to the V arm 5′-stem are maintained for allosteric contacts. No structure is available currently to test this notion. AlphaFold 3 modeling could perhaps be used to address this issue [39].

Table 1.

Type II tRNA V loops in Archaea (Pfu for Pyrococcus furiosus) and Bacteria (Tth for Thermus thermophilus). NA indicates “not applicable”. The trajectory score is the number of unpaired bases in a type II V loop just 5′ of the Levitt base (Vn).

Above, we have argued that the β-hairpin at the C-terminus of bacterial TyrRS-IC may relate distantly to the β-hairpins at the C-termini of LeuRS-IA (Figure 12). We agree that the sequence match is insufficient to fully demonstrate this idea. If this idea is correct, however, we would argue that the evolution of type II tRNATyr and TyrRS-IC in Bacteria may have been as ancient an occurrence as the initial divergence of Archaea and Bacteria, perhaps as ancient as when all or most type II V arms were 14 nt in length. In such a scenario, Archaea could have adopted a type I tRNATyr and deleted the TyrRS-IC C-terminal domain that was necessary only to recognize a type II tRNATyr. Bacteria would have adopted or maintained a type II tRNATyr and maintained a TyrRS-IC with a C-terminal domain capable of recognizing the type II V arm.

Table 2 summarizes type II V arm and elbow tRNA distal determinants for LeuRS-IA, SerRS-IIA, and TyrRS-IC. Missing data for a full comparison are identified. For LeuRS-IA, Archaea and Bacteria have evolved homologous C-terminal domains that are massively modified and rearranged to make very different tRNA V arm and elbow contacts. In Bacteria, TyrRS-IC has a C-terminal domain that interacts with the V arm end loop and V arm 5′-stem in Thermus thermophilus and probably only the V arm 5′-stem in Escherichia coli (no structure is available). SerRS-IIA utilizes an N-terminal helix hairpin to bind the tRNASer V arm 5′- and 3′-stems and the elbow. LeuRS-IA and SerRS-IIA do not utilize cognate tRNA anticodon recognition, consistent with leucine and serine occupying 6-codon sectors of the genetic code. Serine is the only amino acid that is split between two genetic code columns (columns 2 and 4). As described below, we attempt to explain how SerRS-IIA-tRNASer recognition may have facilitated the jump. Among missing data are (1) archaeal LeuRS-IA-tRNALeu in an editing/proofreading conformation; (2) archaeal SerRS-IIA-tRNASer; and (3) Escherichia coli TyrRS-IC-tRNATyr. We do not know how tRNA elbow recognition affects allosteric communication to a cognate AARS active site(s).

Table 2.

Comparison summary of type II V loop and elbow tRNA allosteric contacts in Archaea and Bacteria. NA for not applicable. Pho for Pyrococcus horikoshii. Tth for Thermus thermophilus.

12. Serine Jumping in Genetic Code Evolution

Serine is the only amino acid that is split between two genetic code columns (columns 2 and 4) (see below). We posit that serine jumping was possible because tRNASer has a type II V loop and SerRS-IIA lacks tRNASer anticodon loop recognition [5,6,7]. We further suggest that serine jumping during genetic code establishment may relate to the incorporation of cysteine into the code. Serine can be converted to cysteine through tRNA-linked chemistry [17,18,19]. Because cysteine is important for Zn binding, there is reason to believe that cysteine was an early addition to the genetic code. First proteins that coevolved with the code may have utilized Zn binding for their initial folding [49]. Cysteine, however, now occupies disfavored row 1 (tRNA-36A) of the genetic code, indicating that cysteine may have been a late addition. Row 1 (tRNA-36A) appears to be the last row of the code to fill. Complex aromatic amino acids (phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan) and stop codons locate to row 1 of the code, indicating that row 1 filled late [50]. It has been posited that row 1 filled late because tRNA-36 was initially a wobble position [5,6,7]. Unmodified A is not observed in a wobble position in Archaea (no unmodified tRNA-34A). The suppression of wobbling at tRNA-36A involved a tightening conformation (closing) of the 30S ribosomal subunit [51,52,53,54,55] and modifications of tRNA-37 [16]. At the base of code evolution, it appears that tRNA-37m1G was necessary to read tRNA-36A and tRNA-37t6A was necessary to read tRNA-36U. Such observations are consistent with tRNA-36 having been a wobble position before wobbling could be suppressed.

We suggest that serine jumped from column 2 to column 4 from an enlarged serine block within the code (i.e., tRNASer (GGU → GCU)). Cysteine, however, may have entered the genetic code by the modification of serine (i.e., Ser-tRNACys → Cys-tRNACys through tRNA-linked chemistry) [17,18,19]. In this way, cysteine could have invaded the genetic code early but settled in its final position in the code late (tRNACys (GCA)). Anticodon GGU now encodes threonine, which is chemically related to serine. We are suggesting that both serine conversion to cysteine by tRNA-linked chemistry and type II tRNASer V arm recognition by SerRS-IIA may have enabled serine jumping from column 2 to column 4 of the genetic code. Serine jumping during code establishment is of interest because this is some of the only observed chaos in the evolution of the code [5,6,7].

13. Type II tRNA Evolution and the Origin of the Genetic Code

The effort to understand type II tRNA diversification at the origin of life and during the great divergence at LUCA of Archaea and Bacteria is part of a larger effort to understand the evolution of the genetic code [1,5,6,7,56,57]. Type I and type II tRNAs were sorted very early in evolution. Type II tRNALeu and tRNASer appear to have been sorted before divergence of Archaea and Bacteria. Type II tRNATyr was subsequently adopted in Bacteria but rejected in Archaea. The number of type II tRNAs in a prokaryote was limited by the number of potential trajectory set points of the V arm. Archaea adopted two set points. Bacteria adopted three. In Bacteria, having three type II V arm trajectory set points is correlated with the expansion of tRNASer V arm stems. We posit that the adoption of three trajectory set points for type II V arms in Bacteria (1) resulted in lengthening of tRNASer V arm stems; (2) altered the set points of tRNALeu and tRNASer V arms; (3) caused alterations in how the tRNALeu V arm and elbow are utilized as determinants for LeuRS-IA recognition; and (4) contributed to divergence of Archaea and Bacteria.

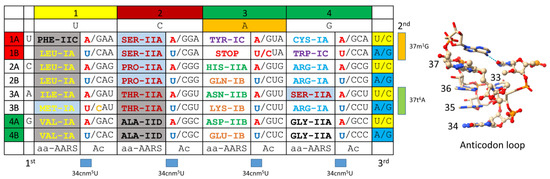

Figure 14 shows an archaeal codon–anticodon table [5,6,7,49]. The complexity of the code is a maximum of 32 assignments. The table lists the encoded amino acid and its cognate AARS. Colors emphasize related amino acids and AARS enzymes that mostly align in columns. To suppress superwobbling and allow 2-codon sectors, U must be modified by methylation at the 5-carbon (i.e., tRNA-34cnm5U) [16]. Most evolution is in code columns (tRNA-35). Columns 1, 2, and 4 contain 4- and 6-codon sectors. Column 3 is entirely 2-codon sectors. Rows 1, 2, 3, and 4 relate to tRNA-36. Only purine–pyrimidine discrimination is achieved at a wobble position (tRNA-34; A and B rows).

Figure 14.

The archaeal genetic code as a codon–anticodon table (maximum complexity, 32 assignments). (aa-AARS) Amino acid-aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (class I or II and subclass A, B, C, or D); (Ac) anticodon. (1st, 2nd, 3rd) Codon. Colors were selected to emphasize similar amino acids and AARS enzymes. Red bases in the anticodon are not utilized. Blue U indicates a modified tRNA-34cnm5U or similar modification to suppress superwobbling. Orange C indicates differential anticodon C*AU modification. In Archaea, C* is agmatidine to encode isoleucine. C* is methylated to encode elongator methionine, and C is unmodified for initiator methionine. Gray shading indicates AARS enzymes with separate editing/proofreading active sites. Light blue shading indicates AARS enzymes with editing functions in the aminoacylating active site. Similar colors indicate similar amino acids or AARS. 37m1G evolved to read tRNA-36A. 37t6A evolved to read tRNA-36U. To the right of the figure, a structure of the anticodon loop is shown. Bases indicated in ball and stick representation are modified bases [23].

The genetic code is highly ordered. Significant evolution is observed in genetic code columns. Related amino acids Leu, Ile, Met, and Val locate to column 1 of the code. LeuRS-IA, IleRS-IA, MetRS-IA, and ValRS-IA are all closely homologous class IA AARS enzymes. Ser and Thr are chemically related amino acids, and Ser, Pro, Thr, and Ala are neutral amino acids that locate to column 2. SerRS-IIA, ProRS-IIA, and ThrRS-IIA are closely homologous class IIA AARS enzymes. AlaRS-IID is a significantly different AARS, which may have replaced a now extinct AlaRS-IIA before LUCA to suppress translation errors. In Archaea, in column 3, an ordered striped pattern is observed. His, Asn, and Asp occupy column 3, and rows 2A, 3A, and 4A (tRNA-34G). HisRS-IIA, AsnRS-IIB, and AspRS-IIB are closely homologous AARSs. Gln, Lys, and Glu occupy column 3, and rows 2B, 3B, and 4B (tRNA-34U*/C; U* is modified U to suppress superwobbling; i.e., tRNA-34cnm5U) [16]. GlnRS-IB, LysRS-IB (in Archaea), and GluRS-IB are closely homologous AARSs. In column 4, CysRS-IA and ArgRS-IA are closely homologous class IA AARSs. Glycine occupies the most favored sector in the genetic code: column 4 (tRNA-35C) and row 4 (tRNA-36C).

It appears that glycine was the first encoded amino acid (tRNA-35C, tRNA36C) [5,6,7,58,59]. Glycine, alanine, aspartic acid, and valine (GADV) are the simplest amino acids that occupy the most favored row 4 (tRNA-36C). It appears that GADV were the first four encoded amino acids [60,61,62,63,64,65]. An adequate model for the evolution of the genetic code must specify an order of the addition of amino acids into the code. An adequate model for the evolution of the code must account for the evolution of 6-codon sectors (Leu, Ser, and Arg), 4-codon sectors (Val, Pro, Thr, Ala, and Gly), the 3-codon sector (Ile), 2-codon sectors (Phe, Tyr, His, Gln, Asn, Lys, Asp, Glu, and Cys), and 1-codon sectors (Met and Trp). Leu and Ser occupy 6-codon sectors, and tRNALeu and tRNASer are type II tRNAs that utilize their longer V arms for LeuRS-IA and SerRS-IIA recognition and discrimination. ArgRS-IA, which utilizes a type I tRNAArg, unwinds the anticodon loop to better recognize this feature (Figure 10) [37]. An adequate model for code evolution must rationalize why leucine and serine utilize type II tRNAs and occupy 6-codon sectors. An adequate model must rationalize serine jumping between column 2 and column 4 of the genetic code.

The genetic code evolved around tRNA and the tRNA anticodon [5,6,7,49]. Degeneracy explains why the genetic code encodes 21 assignments: 20 amino acids plus stops. The genetic code has the capacity to encode up to 32 assignments (Figure 14). At a wobble position (tRNA-34), only purine versus pyrimidine resolution has been achieved. At Watson–Crick positions (tRNA-35 and tRNA-36), codon A, G, C, and U can be read. Thus, the code was limited by tRNA reading to 2 × 4 × 4 = 32 assignments. But, tRNA-34 (wobble) and tRNA-36 positions show similarities for the utilization of weakly pairing bases U and A. At tRNA-34, tRNA-34U must be modified to suppress “superwobbling” [16]. Superwobbling, in which tRNA-34U reads mRNA wobble A, G, C, and U (as in mitochondria), can only be utilized in a 4-codon box [66,67]. To support 2-codon sectors, tRNA-34U must be modified to restrict its reading (i.e., tRNA-34cnm5U; 5-cyanomethyluridine). In Archaea, tRNA-34A is not observed. At tRNA-36, at the base of the code, tRNA-36A is supported by adjacent tRNA-37m1G modification. Also, tRNA-36U is supported by adjacent tRNA-37t6A modification. We posit that tRNA-34 and tRNA-36 were originally both wobble positions, and only a single wobble position could be read at a time. With both tRNA-34 and tRNA-36 as wobble positions, the complexity of the genetic code was 8 assignments (2 × 4 or 4 × 2) (only one wobble position could be read at a time). When tRNA-36 was a wobble position, we posit that columns 1, 2, and 4 of the genetic code evolved primarily around tRNA-35 (Watson–Crick) and tRNA-36 (wobble). Column 3 of the genetic code evolved around tRNA-34 (wobble) and tRNA-35 (Watson–Crick). This explains why 6-, 4-, and 3-codon boxes locate to columns 1, 2, and 4. This also explains why only 2-codon boxes are found in column 3, and why column 3 fractionates on A and B rows (tRNA-34; wobble).

Because tRNA-36 was originally a wobble position, we posit that disfavored row 1 of the genetic code (tRNA-36A) was the last row to fill. Stop codons locate to disfavored row 1. Stop codons are read by protein release factors that read the mRNA codon directly, so there is no tRNA that corresponds to a stop codon (except in suppressor strains) [68]. Aromatic amino acids Phe, Tyr, and Trp locate to row 1. Phe, Tyr, and Trp are the most complex amino acids, so it is reasonable that they were added late after wobbling was suppressed at tRNA-36 [50]. The suppression of wobbling at tRNA-36 was partly via tRNA-37m1G modification to read tRNA-36A and tRNA-37t6A modification to read tRNA-36U. To suppress tRNA-36 wobbling, a conformational change in the 30S ribosomal subunit tightens the anticodon–codon interaction, dehydrates the bases to promote pairing, and locks the translation frame that helps to maintain translational fidelity and, also, helps to set the reading frame in place [51,52,53,54,55,69,70,71]. Wobbling cannot be suppressed in the same manner at tRNA-34 because the modification of adjacent bases does not assist tRNA-34 reading. The modification of tRNA-33 will not help to suppress tRNA-34 wobbling because tRNA-33 is on the other side of the anticodon loop U-turn. Also, tRNA-35 cannot be easily modified because this is a Watson–Crick base that must pair with mRNA. Too many different and constrained tRNA-35 modifications might be necessary (i.e., 2–4) to suppress wobbling at tRNA-34 for such a mechanism to evolve.

In the pre-life world, RNA-linked and tRNA-linked chemistries were common. In the evolution of the genetic code, tRNA-linked reactions may have promoted the incorporation of leucine (Val → Leu; five steps), tyrosine (Phe → Tyr; one step), glutamine (Glu → Gln; one step), asparagine (Asp → Asn; one step) [72,73], arginine (Orn → Arg; two steps; Orn for ornithine) [74], and cysteine (Ser → Cys; two steps) [17,18,19]. Because of tRNA-linked reactions, an 8-amino-acid genetic code can be significantly enriched to encode the first RNA sequence-dependent proteins. For instance, in addition to encoding GADVLSER, an 8 aa code with tRNA-34 and tRNA-36 wobbling could also utilize CQN through tRNA-linked reactions.

Adopting a tRNA-centric view of pre-life chemical evolution indicates that the genetic code was initially utilized to generate polyglycine, a component of protocells [5,6,7]. Subsequently, the code progressed to generate GADV polymers. Then, probably, GADVLSER was encoded with CQN added through tRNA-linked chemistry. Leucine and serine, therefore, may have entered the code at about the same time to utilize type II tRNAs and to eventually settle into 6-codon boxes. First RNA sequence-dependent proteins and enzymes emerged at about the 11-amino-acid stage. The suppression of tRNA-36 wobbling allowed the code to expand. The code froze at 20 amino acids plus stops because of fidelity mechanisms.

We consider the utilization of type II tRNALeu, tRNASer, and tRNATyr (in Bacteria) to support this narrative.

14. Conclusions

We conclude that type II V loops in Archaea and Bacteria relay a simple story about the original sorting of type I and type II tRNAs. In a domain (i.e., Archaea and Bacteria), sets of synonymous type II tRNA V loops must have distinct trajectory set points determined by the number of unpaired bases just 5′ of the Levitt base (Vn). For Archaea, tRNALeu has a set point of 2, and tRNASer has a set point of 1. For Bacteria, tRNATyr has a set point of 2. To accommodate a type II tRNATyr with a set point of 2 in Bacteria, tRNALeu has a set point of 1, and tRNASer has a set point of 0. The longer lengths of the tRNASer V arm stems in Bacteria may relate to the need to stabilize the V2 = V(n−1) base pair. Sharing tRNAs between Archaea and Bacteria is awkward, in part, because of the incompatibility of type II tRNAs. Also, tRNA modification systems in Archaea and Bacteria are largely incompatible.

As organisms became more derived in evolution, V arm end loop contacts by a cognate AARS appear to have given way to V arm stem contacts. This trend appears to be supported by LeuRS-IA-tRNALeu V arm end loop contacts in Archaea being replaced by LeuRS-IA-tRNALeu V arm 3′-stem contacts in Bacteria. Also, V arm end loop and 5′-stem contacts in TyrRS-IC-tRNATyr of Thermus thermophilus appear to give way to V arm 5′-stem contacts in TyrRS-IC-tRNATyr of Escherichia coli (no structure is currently available). We posit that V arm stem contacts may exert greater allosteric communication to the tRNA 3′-end compared to V arm end loop contacts, which would be expected to be more flexible and more weakly allosteric than contacts to a V arm stem.

The three 31 nt minihelix tRNA evolution theorem completely describes the evolution of type I and type II tRNAs, to the last nucleotide (Figure 1) [1]. The reason that tRNA evolution could be solved with such high confidence is that tRNA sequences chemically evolved from RNA repeats and inverted repeats conserved from pre-life. The solution of type II tRNA evolution was predicted based on the model for type I tRNA evolution, making the three 31 nt minihelix tRNA evolution theorem powerfully predictive [3]. The evolution of type II tRNAs in Archaea and Bacteria is fully supportive of the theorem. The evolution of type I and type II tRNAs comprises the core, successful and conserved strategy, and pathway in the evolution of life on Earth. After ~4 billion years, it is remarkable that such a clear record of pre-life worlds survived in the tRNA sequences of living organisms.

Author Contributions

L.L. and Z.F.B. wrote the paper and prepared the figures. The authors have read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable (only appropriate if no new data is generated or the article describes entirely theoretical research). No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lei, L.; Burton, Z.F. The 3 31 Nucleotide Minihelix tRNA Evolution Theorem and the Origin of Life. Life 2023, 13, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, Z.F. The 3-Minihelix tRNA Evolution Theorem. J. Mol. Evol. 2020, 88, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Kowiatek, B.; Opron, K.; Burton, Z.F. Type-II tRNAs and Evolution of Translation Systems and the Genetic Code. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, D.; Du, N.; Kim, Y.; Sun, Y.; Burton, Z.F. Rooted tRNAomes and evolution of the genetic code. Transcription 2018, 9, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, L.; Burton, Z.F. Evolution of the genetic code. Transcription 2021, 12, 28–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, L.; Burton, Z.F. Evolution of Life on Earth: tRNA, Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases and the Genetic Code. Life 2020, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Opron, K.; Burton, Z.F. A tRNA- and Anticodon-Centric View of the Evolution of Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases, tRNAomes, and the Genetic Code. Life 2019, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pak, D.; Root-Bernstein, R.; Burton, Z.F. tRNA structure and evolution and standardization to the three nucleotide genetic code. Transcription 2017, 8, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Root-Bernstein, R.; Kim, Y.; Sanjay, A.; Burton, Z.F. tRNA evolution from the proto-tRNA minihelix world. Transcription 2016, 7, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, P.P.; Lowe, T.M. tRNAscan-SE: Searching for tRNA Genes in Genomic Sequences. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1962, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, T.M.; Chan, P.P. tRNAscan-SE On-line: Integrating search and context for analysis of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W54–W57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P.P.; Lowe, T.M. GtRNAdb 2.0: An expanded database of transfer RNA genes identified in complete and draft genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D184–D189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhling, F.; Morl, M.; Hartmann, R.K.; Sprinzl, M.; Stadler, P.F.; Putz, J. tRNAdb 2009: Compilation of tRNA sequences and tRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, D159–D162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Burton, Z.F. Early Evolution of Transcription Systems and Divergence of Archaea and Bacteria. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 651134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spellman, C.D.; Burton, Z.T.; Ikuma, K.; Strosnider, W.H.J.; Tasker, T.L.; Roman, B.; Goodwill, J.E. Continuous co-treatment of mine drainage with municipal wastewater. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 354, 120282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Burton, Z.F. “Superwobbling” and tRNA-34 Wobble and tRNA-37 Anticodon Loop Modifications in Evolution and Devolution of the Genetic Code. Life 2022, 12, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukai, T.; Crnkovic, A.; Umehara, T.; Ivanova, N.N.; Kyrpides, N.C.; Soll, D. RNA-Dependent Cysteine Biosynthesis in Bacteria and Archaea. mBio 2017, 8, e00561-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turanov, A.A.; Xu, X.M.; Carlson, B.A.; Yoo, M.H.; Gladyshev, V.N.; Hatfield, D.L. Biosynthesis of selenocysteine, the 21st amino acid in the genetic code, and a novel pathway for cysteine biosynthesis. Adv. Nutr. 2011, 2, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauenstein, S.I.; Perona, J.J. Redundant synthesis of cysteinyl-tRNACys in Methanosarcina mazei. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 22007–22017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Macnamara, L.M.; Leuchter, J.D.; Alexander, R.W.; Cho, S.S. MD Simulations of tRNA and Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases: Dynamics, Folding, Binding, and Allostery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 15872–15902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giege, R.; Springer, M. Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases in the Bacterial World. EcoSal Plus 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P.P.; Lowe, T.M. GtRNAdb: A database of transfer RNA genes detected in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, D93–D97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Moore, P.B. The crystal structure of yeast phenylalanine tRNA at 1.93 A resolution: A classic structure revisited. RNA 2000, 6, 1091–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukunaga, R.; Yokoyama, S. Aminoacylation complex structures of leucyl-tRNA synthetase and tRNALeu reveal two modes of discriminator-base recognition. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005, 12, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, E.C.; Goddard, T.D.; Pettersen, E.F.; Couch, G.S.; Pearson, Z.J.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Tools for structure building and analysis. Protein Sci. 2023, 32, e4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Meng, E.C.; Couch, G.S.; Croll, T.I.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. 2021, 30, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Meng, E.C.; Pettersen, E.F.; Couch, G.S.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Sci. 2018, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukunaga, R.; Yokoyama, S. Crystal structure of leucyl-tRNA synthetase from the archaeon Pyrococcus horikoshii reveals a novel editing domain orientation. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 346, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaremchuk, A.; Kriklivyi, I.; Tukalo, M.; Cusack, S. Class I tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase has a class II mode of cognate tRNA recognition. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 3829–3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palencia, A.; Crepin, T.; Vu, M.T.; Lincecum, T.L., Jr.; Martinis, S.A.; Cusack, S. Structural dynamics of the aminoacylation and proofreading functional cycle of bacterial leucyl-tRNA synthetase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012, 19, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulic, M.; Cvetesic, N.; Zivkovic, I.; Palencia, A.; Cusack, S.; Bertosa, B.; Gruic-Sovulj, I. Kinetic Origin of Substrate Specificity in Post-Transfer Editing by Leucyl-tRNA Synthetase. J. Mol. Biol. 2018, 430, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biou, V.; Yaremchuk, A.; Tukalo, M.; Cusack, S. The 2.9 A crystal structure of T. thermophilus seryl-tRNA synthetase complexed with tRNA(Ser). Science 1994, 263, 1404–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Guo, Y.; Tian, Q.; Jia, Q.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, C.; Xie, W. SerRS-tRNASec complex structures reveal mechanism of the first step in selenocysteine biosynthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 10534–10545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belrhali, H.; Yaremchuk, A.; Tukalo, M.; Berthet-Colominas, C.; Rasmussen, B.; Bosecke, P.; Diat, O.; Cusack, S. The structural basis for seryl-adenylate and Ap4A synthesis by seryl-tRNA synthetase. Structure 1995, 3, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafels-Ybern, A.; Torres, A.G.; Camacho, N.; Herencia-Ropero, A.; Roura Frigole, H.; Wulff, T.F.; Raboteg, M.; Bordons, A.; Grau-Bove, X.; Ruiz-Trillo, I.; et al. The Expansion of Inosine at the Wobble Position of tRNAs, and Its Role in the Evolution of Proteomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2019, 36, 650–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafels-Ybern, A.; Torres, A.G.; Grau-Bove, X.; Ruiz-Trillo, I.; Ribas de Pouplana, L. Codon adaptation to tRNAs with Inosine modification at position 34 is widespread among Eukaryotes and present in two Bacterial phyla. RNA Biol. 2018, 15, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delagoutte, B.; Moras, D.; Cavarelli, J. tRNA aminoacylation by arginyl-tRNA synthetase: Induced conformations during substrates binding. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 5599–5610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Nureki, O.; Ishitani, R.; Yaremchuk, A.; Tukalo, M.; Cusack, S.; Sakamoto, K.; Yokoyama, S. Structural basis for orthogonal tRNA specificities of tyrosyl-tRNA synthetases for genetic code expansion. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003, 10, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Vishveshwara, S. A study of communication pathways in methionyl- tRNA synthetase by molecular dynamics simulations and structure network analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 15711–15716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Nandi, N. Dynamics of the Catalytic Active Site of Isoleucyl tRNA Synthetase from Staphylococcus aureus bound with Adenylate and Mupirocin. J. Phys. Chem. B 2022, 126, 620–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Nandi, N. Role of the transfer ribonucleic acid (tRNA) bound magnesium ions in the charging step of aminoacylation reaction in the glutamyl tRNA synthetase and the seryl tRNA synthetase bound with cognate tRNA. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 40, 8538–8559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Nandi, N. Classical molecular dynamics simulation of seryl tRNA synthetase and threonyl tRNA synthetase bound with tRNA and aminoacyl adenylate. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2019, 37, 336–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Kundu, S.; Saha, A.; Nandi, N. Dynamics of the active site loops in catalyzing aminoacylation reaction in seryl and histidyl tRNA synthetases. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2018, 36, 878–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Larios, A.; Sankaranarayanan, R.; Rees, B.; Dock-Bregeon, A.C.; Moras, D. Conformational movements and cooperativity upon amino acid, ATP and tRNA binding in threonyl-tRNA synthetase. J. Mol. Biol. 2003, 331, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayevsky, A.V.; Sharifi, M.; Tukalo, M.A. Molecular modeling and molecular dynamics simulation study of archaeal leucyl-tRNA synthetase in complex with different mischarged tRNA in editing conformation. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2017, 76, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, Z.F.; Opron, K.; Wei, G.; Geiger, J.H. A model for genesis of transcription systems. Transcription 2016, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Burton, S.P.; Burton, Z.F. The sigma enigma: Bacterial sigma factors, archaeal TFB and eukaryotic TFIIB are homologs. Transcription 2014, 5, e967599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, D.; Kim, Y.; Burton, Z.F. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase evolution and sectoring of the genetic code. Transcription 2018, 9, 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, G.P.; Alm, E.J. Ancestral Reconstruction of a Pre-LUCA Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetase Ancestor Supports the Late Addition of Trp to the Genetic Code. J. Mol. Evol. 2015, 80, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozov, A.; Wolff, P.; Grosjean, H.; Yusupov, M.; Yusupova, G.; Westhof, E. Tautomeric G*U pairs within the molecular ribosomal grip and fidelity of decoding in bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 7425–7435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozov, A.; Demeshkina, N.; Westhof, E.; Yusupov, M.; Yusupova, G. New Structural Insights into Translational Miscoding. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016, 41, 798–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozov, A.; Westhof, E.; Yusupov, M.; Yusupova, G. The ribosome prohibits the G*U wobble geometry at the first position of the codon-anticodon helix. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 6434–6441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozov, A.; Demeshkina, N.; Westhof, E.; Yusupov, M.; Yusupova, G. Structural insights into the translational infidelity mechanism. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveland, A.B.; Demo, G.; Grigorieff, N.; Korostelev, A.A. Ensemble cryo-EM elucidates the mechanism of translation fidelity. Nature 2017, 546, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E.V.; Novozhilov, A.S. Origin and Evolution of the Universal Genetic Code. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2017, 51, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E.V.; Novozhilov, A.S. Origin and evolution of the genetic code: The universal enigma. IUBMB Life 2009, 61, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, H.S.; Patrick, W.M. Genetic code evolution started with the incorporation of glycine, followed by other small hydrophilic amino acids. J. Mol. Evol. 2014, 78, 307–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, H.S.; Tate, W.P. Evidence from glycine transfer RNA of a frozen accident at the dawn of the genetic code. Biol. Direct. 2008, 3, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikehara, K. Why Were [GADV]-amino Acids and GNC Codons Selected and How Was GNC Primeval Genetic Code Established? Genes 2023, 14, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikehara, K. Evolutionary Steps in the Emergence of Life Deduced from the Bottom-Up Approach and GADV Hypothesis (Top-Down Approach). Life 2016, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikehara, K. [GADV]-protein world hypothesis on the origin of life. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 2014, 44, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikehara, K. Pseudo-replication of [GADV]-proteins and origin of life. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 1525–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oba, T.; Fukushima, J.; Maruyama, M.; Iwamoto, R.; Ikehara, K. Catalytic activities of [GADV]-peptides. Formation and establishment of [GADV]-protein world for the emergence of life. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 2005, 35, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikehara, K. Possible steps to the emergence of life: The [GADV]-protein world hypothesis. Chem. Rec. 2005, 5, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkatib, S.; Scharff, L.B.; Rogalski, M.; Fleischmann, T.T.; Matthes, A.; Seeger, S.; Schottler, M.A.; Ruf, S.; Bock, R. The contributions of wobbling and superwobbling to the reading of the genetic code. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1003076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogalski, M.; Karcher, D.; Bock, R. Superwobbling facilitates translation with reduced tRNA sets. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008, 15, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burroughs, A.M.; Aravind, L. The Origin and Evolution of Release Factors: Implications for Translation Termination, Ribosome Rescue, and Quality Control Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeshkina, N.; Jenner, L.; Westhof, E.; Yusupov, M.; Yusupova, G. New structural insights into the decoding mechanism: Translation infidelity via a G.U pair with Watson-Crick geometry. FEBS Lett. 2013, 587, 1848–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeshkina, N.; Jenner, L.; Westhof, E.; Yusupov, M.; Yusupova, G. A new understanding of the decoding principle on the ribosome. Nature 2012, 484, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]