Small RNAs Worm Up Transgenerational Epigenetics Research

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. C. elegans Model Systems for Studying Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance (TEI)

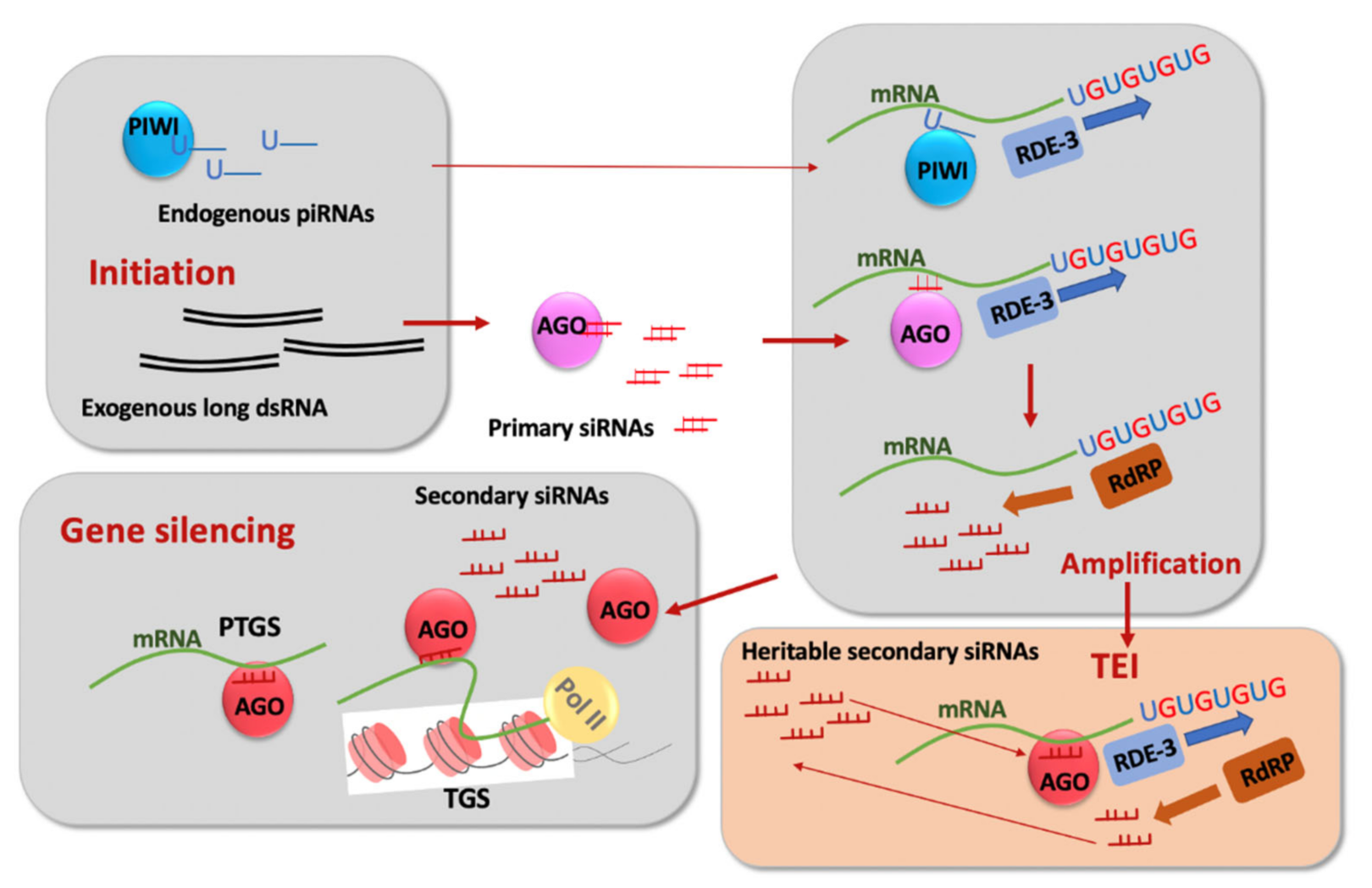

3. RNA-Based and Chromatin-Based Epigenetic Silencing and Their Connections

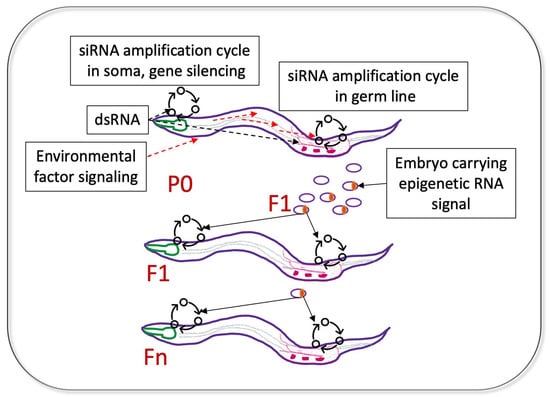

4. Permanent and Limited Forms of TEI and Their Genetic Control

5. Coordination between Gene Silencing in the Soma and Germline; Who Is the Messenger?

6. Sensory Experiences Communicated to the Germ Line and Transmitted Transgenerationally

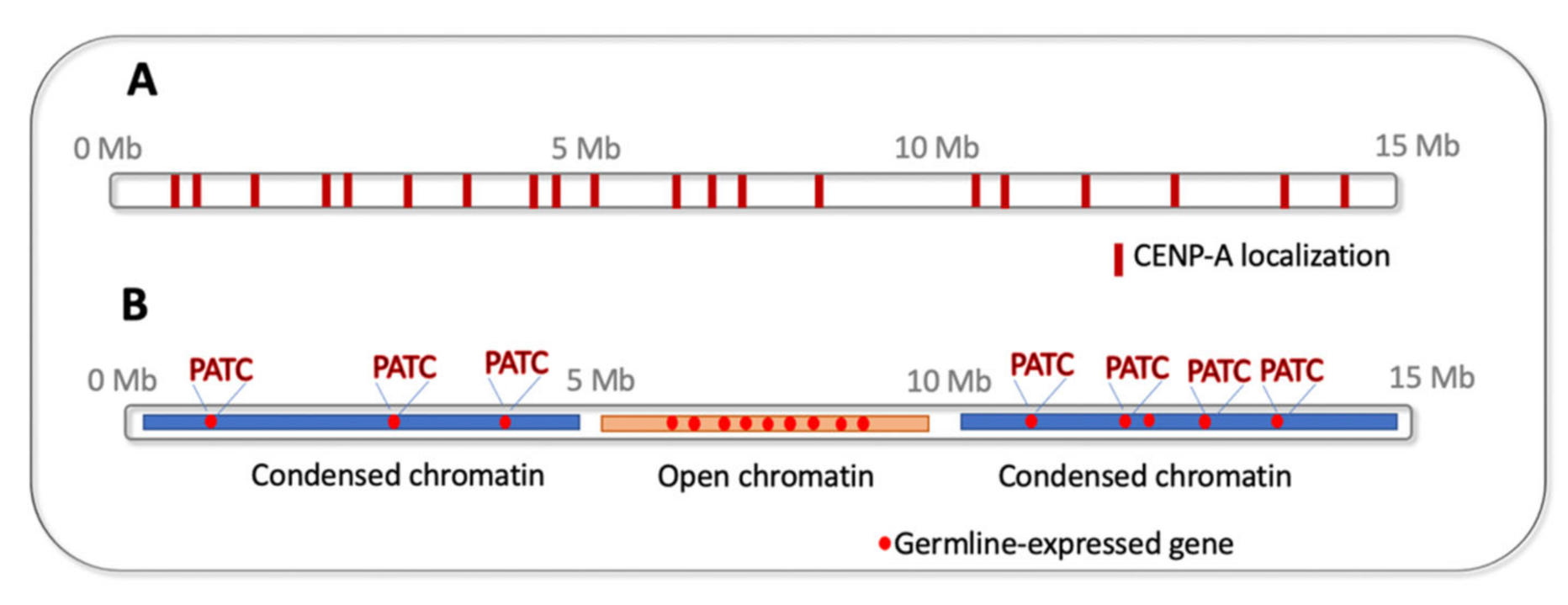

7. Epigenetics of Holocentric Centromeres

8. DNA “Watermarks” Allowing Gene Expression in Silenced Chromatin Environment

9. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Corsi, A.K.; Wightman, B.; Chalfie, M. A Transparent Window into Biology: A Primer on Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 2015, 200, 387–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, R.C.; Feinbaum, R.L.; Ambros, V. The, C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 1993, 75, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wightman, B.; Ha, I.; Ruvkun, G. Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell 1993, 75, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, B.J.; Slack, F.; Basson, M.; Pasquinelli, A.E.; Bettinger, J.C.; Rougvie, A.E.; Horvitz, H.R.; Ruvkun, G. The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 2000, 403, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquinelli, A.E.; Reinhart, B.J.; Slack, F.; Martindale, M.Q.; Kuroda, M.I.; Maller, B.; Hayward, D.C.; Ball, E.; Degnan, B.; Müller, P.; et al. Conservation of the sequence and temporal expression of let-7 heterochronic regulatory RNA. Nature 2000, 408, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupaimoole, R.; Slack, F.J. MicroRNA therapeutics: Towards a new era for the management of cancer and other diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donkin, I.; Barrès, R. Sperm epigenetics and influence of environmental factors. Mol. Metab. 2018, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rechavi, O.; Lev, I. Principles of Transgenerational Small RNA Inheritance in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, R720–R730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perez, M.F.; Lehner, B. Intergenerational and transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in animals. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baugh, L.R.; Day, T. Nongenetic inheritance and multigenerational plasticity in the nematode C. elegans. eLife 2020, 9, e58498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manterola, M.; Palominos, M.F.; Calixto, A. The Heritability of Behaviors Associated with the Host Gut Microbiota. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolows, N.; Ashe, A. Small RNAs and chromatin in the multigenerational epigenetic landscape of Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2021, 376, 20200112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minkina, O.; Hunter, C.P. Intergenerational Transmission of Gene Regulatory Information in Caenorhabditis elegans. Trends Genet. 2017, 34, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Kemphues, K.J. par-1, a gene required for establishing polarity in C. elegans embryos, encodes a putative Ser/Thr kinase that is asymmetrically distributed. Cell 1995, 81, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fire, A.; Albertson, D.; Harrison, S.; Moerman, D. Production of antisense RNA leads to effective and specific inhibition of gene expression in C. elegans muscle. Development 1991, 113, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fire, A.; Xu, S.; Montgomery, M.K.; Kostas, S.A.; Driver, S.E.; Mello, C.C. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 1998, 391, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocheleau, C.E.; Downs, W.D.; Lin, R.; Wittmann, C.; Bei, Y.; Cha, Y.-H.; Ali, M.; Priess, J.R.; Mello, C.C. Wnt Signaling and an APC-Related Gene Specify Endoderm in Early, C. elegans Embryos. Cell 1997, 90, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamilton, A.J. A Species of Small Antisense RNA in Posttranscriptional Gene Silencing in Plants. Science 1999, 286, 950–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grishok, A.; Tabara, H.; Mello, C.C. Genetic Requirements for Inheritance of RNAi in C.elegans. Science 2000, 287, 2494–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smardon, A.; Spoerke, J.M.; Stacey, S.C.; Klein, M.E.; Mackin, N.; Maine, E.M. EGO-1 is related to RNA-directed RNA polymerase and functions in germ-line development and RNA interference in C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 2000, 10, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grishok, A. Biology and Mechanisms of Short RNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Adv. Genet. 2013, 83, 1–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pak, J.; Fire, A. Distinct Populations of Primary and Secondary Effectors During RNAi in C. elegans. Science 2006, 315, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tsai, H.-Y.; Chen, C.-C.G.; Conte, D.; Moresco, J.; Chaves, D.A.; Mitani, S.; Yates, J.R.; Tsai, M.-D.; Mello, C.C. A Ribonuclease Coordinates siRNA Amplification and mRNA Cleavage during RNAi. Cell 2015, 160, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maniar, J.M.; Fire, A.Z. EGO-1, a C. elegans RdRP, Modulates Gene Expression via Production of mRNA-Templated Short Antisense RNAs. Curr. Biol. 2011, 21, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.-C.G.; Simard, M.; Tabara, H.; Brownell, D.R.; McCollough, J.A.; Mello, C.C. A Member of the Polymerase β Nucleotidyltransferase Superfamily Is Required for RNA Interference in C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 2005, 15, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shukla, A.; Yan, J.; Pagano, D.J.; Dodson, A.E.; Fei, Y.; Gorham, J.; Seidman, J.G.; Wickens, M.; Kennedy, S. poly (UG)-tailed RNAs in genome protection and epigenetic inheritance. Nature 2020, 582, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, M.; Porter, D.F.; Chen, F.; Buter, N.; Lapointe, C.P.; Keles, S.; Kimble, J.; Wickens, M. Unbiased screen of RNA tailing activities reveals a poly (UG) polymerase. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcazar, R.M.; Lin, R.; Fire, A.Z. Transmission Dynamics of Heritable Silencing Induced by Double-Stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 2008, 180, 1275–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Praitis, V.; Casey, E.; Collar, D.; Austin, J. Creation of Low-Copy Integrated Transgenic Lines in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 2001, 157, 1217–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vastenhouw, N.L.; Brunschwig, K.; Okihara, K.L.; Müller, F.; Tijsterman, M.; Plasterk, R.H.A. Long-term gene silencing by RNAi. Nature 2006, 442, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, B.A.; Burkhart, K.B.; Gu, S.G.; Spracklin, G.; Kershner, A.; Fritz, H.; Kimble, J.; Fire, A.; Kennedy, S. A nuclear Argonaute promotes multigenerational epigenetic inheritance and germline immortality. Nature 2012, 489, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frøkjær-Jensen, C.; Davis, M.W.; Hopkins, C.E.; Newman, B.J.; Thummel, J.M.; Olesen, S.-P.; Grunnet, M.; Jorgensen, E.M. Single-copy insertion of transgenes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 1375–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frøkjær-Jensen, C.; Davis, M.; Ailion, M.; Jorgensen, E.M. Improved Mos1-mediated transgenesis in C. elegans. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 117–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashe, A.; Sapetschnig, A.; Weick, E.-M.; Mitchell, J.; Bagijn, M.P.; Cording, A.C.; Doebley, A.-L.; Goldstein, L.D.; Lehrbach, N.; Le Pen, J.; et al. piRNAs Can Trigger a Multigenerational Epigenetic Memory in the Germline of C. elegans. Cell 2012, 150, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Woodhouse, R.; Buchmann, G.; Hoe, M.; Harney, D.J.; Low, J.K.; Larance, M.; Boag, P.; Ashe, A. Chromatin Modifiers SET-25 and SET-32 Are Required for Establishment but Not Long-Term Maintenance of Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 2259–2272.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shirayama, M.; Seth, M.; Lee, H.-C.; Gu, W.; Ishidate, T.; Conte, D.; Mello, C.C. piRNAs Initiate an Epigenetic Memory of Nonself RNA in the C. elegans Germline. Cell 2012, 150, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Minkina, O.; Hunter, C.P. Stable Heritable Germline Silencing Directs Somatic Silencing at an Endogenous Locus. Mol. Cell 2017, 65, 659–670.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Luteijn, M.J.; Van Bergeijk, P.; Kaaij, L.J.T.; Almeida, M.V.; Roovers, E.F.; Berezikov, E.; Ketting, R.F. Extremely stable Piwi-induced gene silencing in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 3422–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, H.-C.; Gu, W.; Shirayama, M.; Youngman, E.; Conte, D.; Mello, C.C. C. elegans piRNAs Mediate the Genome-wide Surveillance of Germline Transcripts. Cell 2012, 150, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bagijn, M.P.; Goldstein, L.D.; Sapetschnig, A.; Weick, E.-M.; Bouasker, S.; Lehrbach, N.; Simard, M.; Miska, E.A. Function, Targets, and Evolution of Caenorhabditis elegans piRNAs. Science 2012, 337, 574–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guang, S.; Bochner, A.F.; Burkhart, K.B.; Burton, N.; Pavelec, D.M.; Kennedy, S. Small regulatory RNAs inhibit RNA polymerase II during the elongation phase of transcription. Nature 2010, 465, 1097–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gu, S.G.; Pak, J.; Guang, S.; Maniar, J.M.; Kennedy, S.; Fire, A. Amplification of siRNA in Caenorhabditis elegans generates a transgenerational sequence-targeted histone H3 lysine 9 methylation footprint. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalinava, N.; Ni, J.Z.; Gajic, Z.; Kim, M.; Ushakov, H.; Gu, S.G. C. elegans Heterochromatin Factor SET-32 Plays an Essential Role in Transgenerational Establishment of Nuclear RNAi-Mediated Epigenetic Silencing. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 2273–2284.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Grishok, A.; Sinskey, J.L.; Sharp, P.A. Transcriptional silencing of a transgene by RNAi in the soma of C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2005, 19, 683–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Burton, N.; Burkhart, K.B.; Kennedy, S. Nuclear RNAi maintains heritable gene silencing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 19683–19688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rechavi, O.; Minevich, G.; Hobert, O. Transgenerational Inheritance of an Acquired Small RNA-Based Antiviral Response in C. elegans. Cell 2011, 147, 1248–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sundby, A.E.; Molnar, R.I.; Claycomb, J.M. Connecting the Dots: Linking Caenorhabditis elegans Small RNA Pathways and Germ Granules. Trends Cell Biol. 2021, 31, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, J.N.; Schisa, J.A.; Priess, J.R. P Granules in the Germ Cells of Caenorhabditis elegans Adults Are Associated with Clusters of Nuclear Pores and Contain RNA. Dev. Biol. 2000, 219, 315–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schreier, J.; Dietz, S.; de Jesus Domingues, A.M.; Seistrup, A.-S.; Nguyen, D.A.H.; Gleason, E.J.; Ling, H.; L’Hernault, S.W.; Phillips, C.M.; Butter, F.; et al. A Membrane-Associated Condensate Drives Paternal Epigenetic Inheritance in C. Elegans. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, W.G.; Xu, S.; Montgomery, M.K.; Fire, A. Distinct Requirements for Somatic and Germline Expression of a Generally Expressed Caernorhabditis elegans Gene. Genetics 1997, 146, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabara, H.; Sarkissian, M.; Kelly, W.G.; Fleenor, J.; Grishok, A.; Timmons, L.; Fire, A.; Mello, C.C. The rde-1 Gene, RNA Interference, and Transposon Silencing in C. elegans. Cell 1999, 99, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sakaguchi, A.; Sarkies, P.; Simon, M.; Doebley, A.-L.; Goldstein, L.D.; Hedges, A.; Ikegami, K.; Alvares, S.M.; Yang, L.; LaRocque, J.; et al. Caenorhabditis elegans RSD-2 and RSD-6 promote germ cell immortality by maintaining small interfering RNA populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E4323–E4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Devanapally, S.; Raman, P.; Chey, M.; Allgood, S.; Ettefa, F.; Diop, M.; Lin, Y.; Cho, Y.E.; Jose, A.M. Mating can initiate stable RNA silencing that overcomes epigenetic recovery. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennecke, J.; Malone, C.D.; Aravin, A.A.; Sachidanandam, R.; Stark, A.; Hannon, G.J. An Epigenetic Role for Maternally Inherited piRNAs in Transposon Silencing. Science 2008, 322, 1387–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ahmed, S.; Hodgkin, J. MRT-2 checkpoint protein is required for germline immortality and telomere replication in C. elegans. Nature 2000, 403, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barucci, G.; Cornes, E.; Singh, M.; Li, B.; Ugolini, M.; Samolygo, A.; Didier, C.; Dingli, F.; Loew, D.; Quarato, P.; et al. Small-RNA-mediated transgenerational silencing of histone genes impairs fertility in piRNA mutants. Nature 2020, 22, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, K.J.; Svendsen, J.M.; Brown, K.C.; Montgomery, E.B.; Marks, T.N.; Vijayasarathy, T.; Parker, D.M.; Nishimura, E.O.; Updike, D.L.; Montgomery, A.T. Widespread roles for piRNAs and WAGO-class siRNAs in shaping the germline transcriptome of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 48, 1811–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wahba, L.; Hansen, L.; Fire, A.Z. An essential role for the piRNA pathway in regulating the ribosomal RNA pool in C. elegans. Dev. Cell 2021, 56, 2295–2312.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Feng, X.; Guang, S. A new layer of rRNA regulation by small interference RNAs and the nuclear RNAi pathway. RNA Biol. 2017, 14, 1492–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perales, R.; Pagano, D.; Wan, G.; Fields, B.D.; Saltzman, A.L.; Kennedy, S.G. Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance Is Negatively Regulated by the HERI-1 Chromodomain Protein. Genetics 2018, 210, 1287–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lev, I.; Seroussi, U.; Gingold, H.; Bril, R.; Anava, S.; Rechavi, O. MET-2-Dependent H3K9 Methylation Suppresses Transgenerational Small RNA Inheritance. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, 1138–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shukla, A.; Perales, R.; Kennedy, S. PiRNAs Coordinate Poly (UG) Tailing to Prevent Aberrant and Permanent Gene Silencing. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frøkjær-Jensen, C.; (King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, Thuwal, Saudi Arabia). Personal communication, 2021.

- Klattenhoff, C.; Theurkauf, W. Biogenesis and germline functions of piRNAs. Development 2008, 135, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Winston, W.M.; Molodowitch, C.; Hunter, C.P. Systemic RNAi in C. elegans Requires the Putative Transmembrane Protein SID-1. Science 2002, 295, 2456–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shih, J.D.; Hunter, C.P. SID-1 is a dsRNA-selective dsRNA-gated channel. RNA 2011, 17, 1057–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jose, A.M.; Smith, J.J.; Hunter, C.P. Export of RNA silencing from C. elegans tissues does not require the RNA channel SID-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 2283–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Devanapally, S.; Ravikumar, S.; Jose, A.M. Double-stranded RNA made in C. elegans neurons can enter the germline and cause transgenerational gene silencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 2133–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rechavi, O.; Houri-Ze’Evi, L.; Anava, S.; Goh, S.; Kerk, S.Y.; Hannon, G.J.; Hobert, O. Starvation-Induced Transgenerational Inheritance of Small RNAs in C. elegans. Cell 2014, 158, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ewe, C.K.; Cleuren, Y.N.T.; Flowers, S.E.; Alok, G.; Snell, R.G.; Rothman, J.H. Natural cryptic variation in epigenetic modulation of an embryonic gene regulatory network. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 13637–13646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palominos, M.F.; Verdugo, L.; Gabaldon, C.; Pollak, B.; Ortíz-Severín, J.; Varas, M.A.; Chávez, F.P.; Calixto, A. Transgenerational Diapause as an Avoidance Strategy against Bacterial Pathogens in Caenorhabditis elegans. mBio 2017, 8, e01234-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moore, R.S.; Kaletsky, R.; Murphy, C.T. Piwi/PRG-1 Argonaute and TGF-β Mediate Transgenerational Learned Pathogenic Avoidance. Cell 2019, 177, 1827–1841.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaletsky, R.; Moore, R.S.; Vrla, G.D.; Parsons, L.R.; Gitai, Z.; Murphy, C.T. C. elegans interprets bacterial non-coding RNAs to learn pathogenic avoidance. Nature 2020, 586, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshe, N.; Eliezer, Y.; Hoch, L.; Itskovits, E.; Ben-Ezra, S.; Zaslaver, A. Inheritance of Associative Memories in C. Elegans Nematodes. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Schroeder, E.A.; Silva-García, C.G.; Hebestreit, K.; Mair, W.B.; Brunet, A. Mono-unsaturated fatty acids link H3K4me3 modifiers to C. elegans lifespan. Nature 2017, 544, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grün, D.; Kirchner, M.; Thierfelder, N.; Stoeckius, M.; Selbach, M.; Rajewsky, N. Conservation of mRNA and Protein Expression during Development of C. elegans. Cell Rep. 2014, 6, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stellfox, M.E.; Bailey, A.O.; Foltz, D.R. Putting CENP-A in its place. Experientia 2012, 70, 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maddox, P.S.; Oegema, K.; Desai, A.; Cheeseman, I.M. Holoer than thou: Chromosome segregation and kinetochore function in C. elegans. Chromosom. Res. 2004, 12, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monen, J.; Maddox, P.S.; Hyndman, F.; Oegema, K.; Desai, A. Differential role of CENP-A in the segregation of holocentric C. elegans chromosomes during meiosis and mitosis. Nature 2005, 7, 1248–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosée, R.F.; Wenda, J.M.; Özdemir, I.; Gabus, C.; Delaney, K.; Schwager, F.; Gotta, M.; Steiner, F.A. Transgenerational inheritance of centromere identity requires the CENP-A N-terminal tail in the C. elegans maternal germ line. PLoS Biol. 2021, 19, e3000968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, C.; Houston, J.; Davis, B.; Gerson-Gurwitz, A.; Monen, J.; Lara-Gonzalez, P.; Oegema, K.; Shiau, A.K.; Desai, A. The N-terminal Tail of C. elegans CENP-A Interacts with KNL-2 and is Essential for Centromeric Chromatin Assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell 2021, 32, mbc.E20–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassmann, R.; Rechtsteiner, A.; Yuen, K.W.; Muroyama, A.; Egelhofer, T.; Gaydos, L.; Barron, F.; Maddox, P.; Essex, A.; Monen, J.; et al. An inverse relationship to germline transcription defines centromeric chromatin in C. elegans. Nature 2012, 484, 534–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gu, W.; Shirayama, M.; Conte, D.; Vasale, J.; Batista, P.J.; Claycomb, J.; Moresco, J.; Youngman, E.M.; Keys, J.; Stoltz, M.J.; et al. Distinct Argonaute-Mediated 22G-RNA Pathways Direct Genome Surveillance in the C. elegans Germline. Mol. Cell 2009, 36, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Claycomb, J.; Batista, P.J.; Pang, K.M.; Gu, W.; Vasale, J.J.; van Wolfswinkel, J.C.; Chaves, D.A.; Shirayama, M.; Mitani, S.; Ketting, R.F.; et al. The Argonaute CSR-1 and Its 22G-RNA Cofactors Are Required for Holocentric Chromosome Segregation. Cell 2009, 139, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avgousti, D.C.; Palani, S.; Sherman, Y.; Grishok, A. CSR-1 RNAi pathway positively regulates histone expression in C. elegans. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 3821–3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cecere, G.; Hoersch, S.; O’Keeffe, S.; Sachidanandam, R.; Grishok, A. Global effects of the CSR-1 RNA interference pathway on the transcriptional landscape. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014, 21, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gushchanskaia, E.S.; Esse, R.; Ma, Q.; Lau, N.C.; Grishok, A. Interplay between small RNA pathways shapes chromatin landscapes in C. elegans. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 5603–5616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Rechtsteiner, A.; Egelhofer, T.A.; Vielle, A.; Latorre, I.; Cheung, M.-S.; Ercan, S.; Ikegami, K.; Jensen, M.; Kolasinska-Zwierz, P.; et al. Broad chromosomal domains of histone modification patterns in C. elegans. Genome Res. 2010, 21, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campos, T.L.; Korhonen, P.K.; Sternberg, P.W.; Gasser, R.B.; Young, N.D. Predicting gene essentiality in Caenorhabditis elegans by feature engineering and machine-learning. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frøkjær-Jensen, C.; Jain, N.; Hansen, L.; Davis, M.W.; Li, Y.; Zhao, D.; Rebora, K.; Millet, J.; Liu, X.; Kim, S.K.; et al. An Abundant Class of Non-coding DNA Can Prevent Stochastic Gene Silencing in the C. elegans Germline. Cell 2016, 166, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Simon, M.; Sarkies, P.; Ikegami, K.; Doebley, A.-L.; Goldstein, L.D.; Mitchell, J.; Sakaguchi, A.; Miska, E.A.; Ahmed, S. Reduced Insulin/IGF-1 Signaling Restores Germ Cell Immortality to Caenorhabditis elegans Piwi Mutants. Cell Rep. 2014, 7, 762–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, D.; Ruvkun, G. Regulation of Caenorhabditis elegans RNA Interference by the daf-2 Insulin Stress and Longevity Signaling Pathway. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2004, 69, 429–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grishok, A. Small RNAs Worm Up Transgenerational Epigenetics Research. DNA 2021, 1, 37-48. https://doi.org/10.3390/dna1020005

Grishok A. Small RNAs Worm Up Transgenerational Epigenetics Research. DNA. 2021; 1(2):37-48. https://doi.org/10.3390/dna1020005

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrishok, Alla. 2021. "Small RNAs Worm Up Transgenerational Epigenetics Research" DNA 1, no. 2: 37-48. https://doi.org/10.3390/dna1020005

APA StyleGrishok, A. (2021). Small RNAs Worm Up Transgenerational Epigenetics Research. DNA, 1(2), 37-48. https://doi.org/10.3390/dna1020005