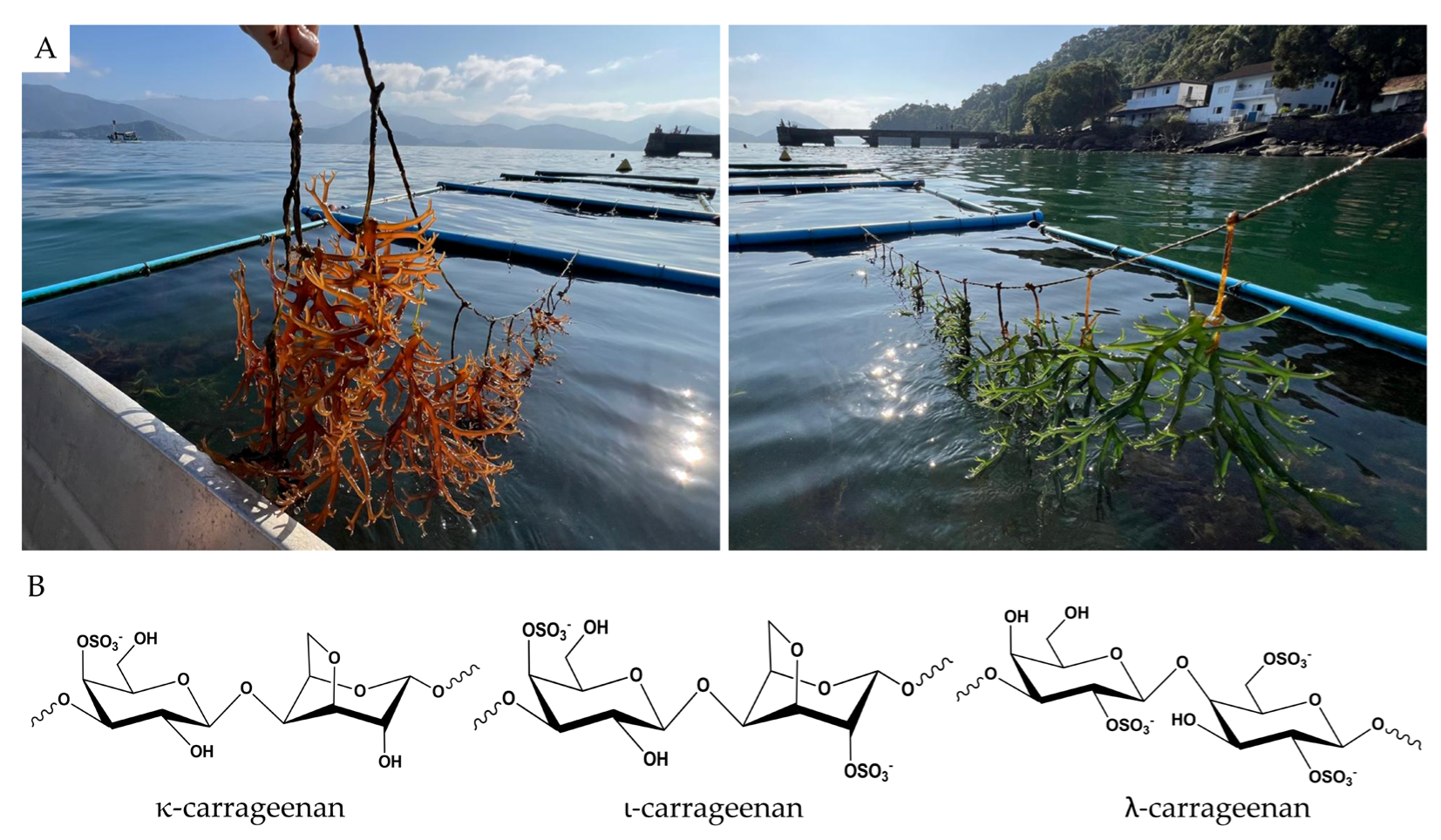

Biotechnological Potential of Carrageenan Extracted from Kappaphycus alvarezii: A Systematic Review of Industrial Applications and Sustainable Innovations

Abstract

1. Introduction

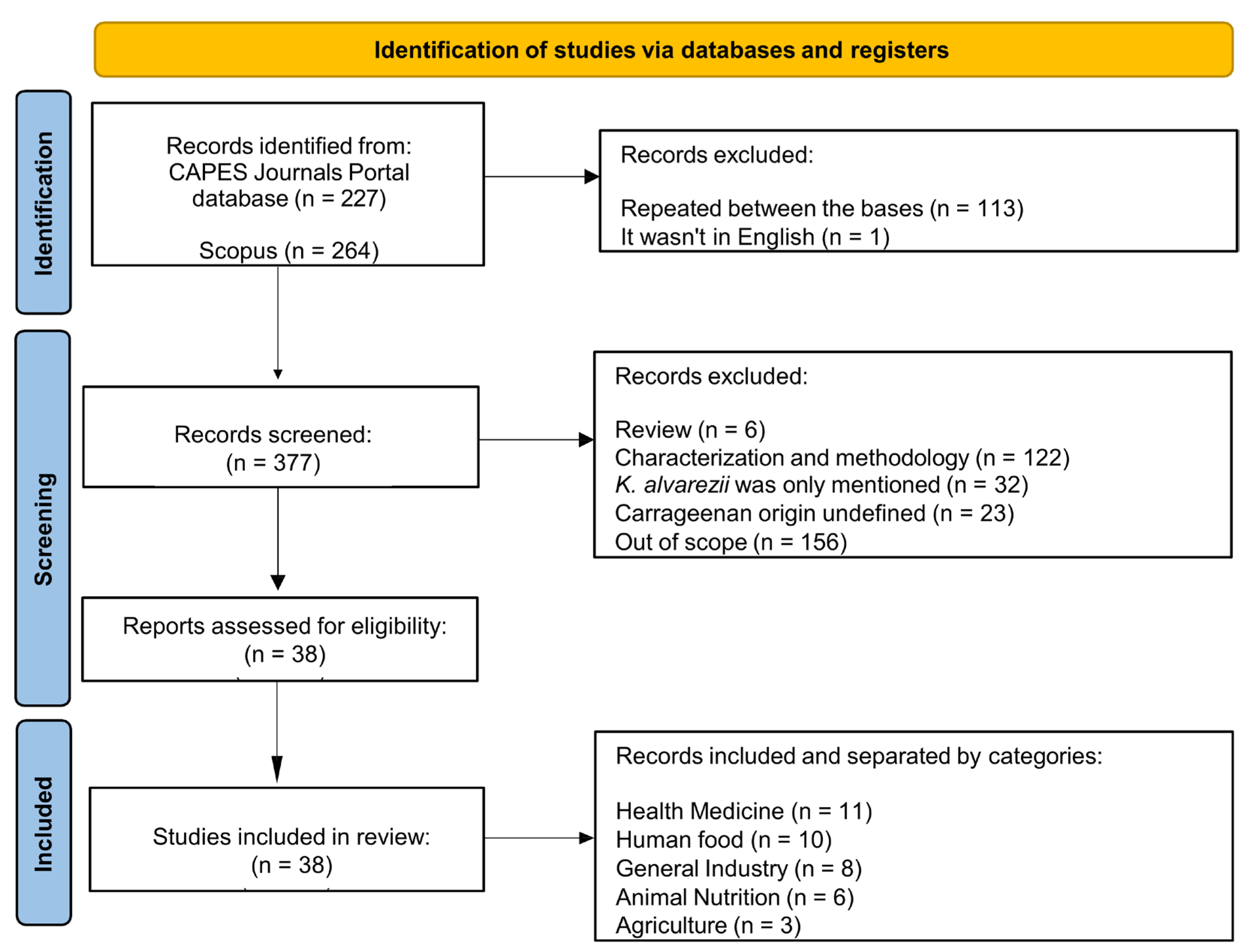

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Quality Assessment

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

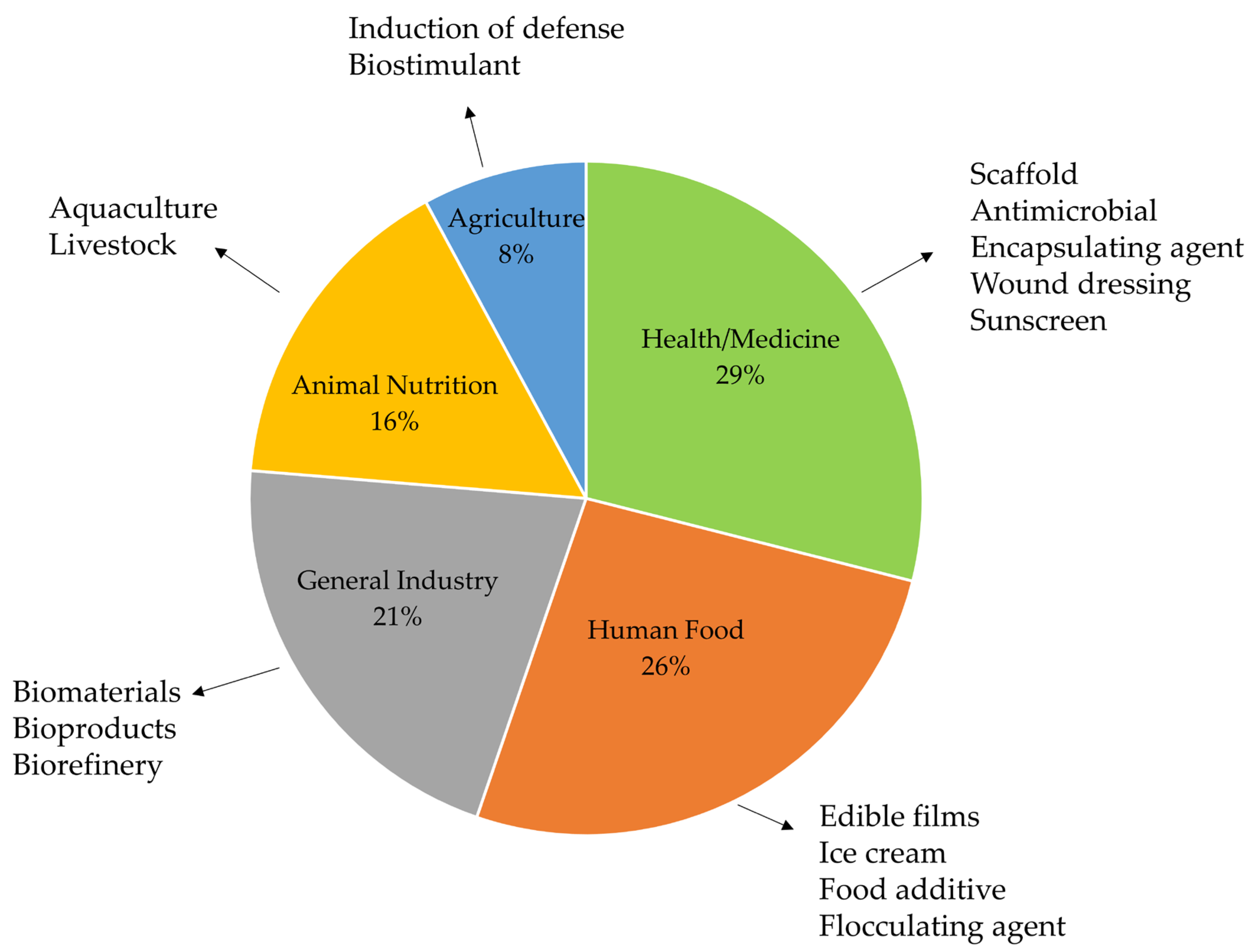

3. Results and Discussion

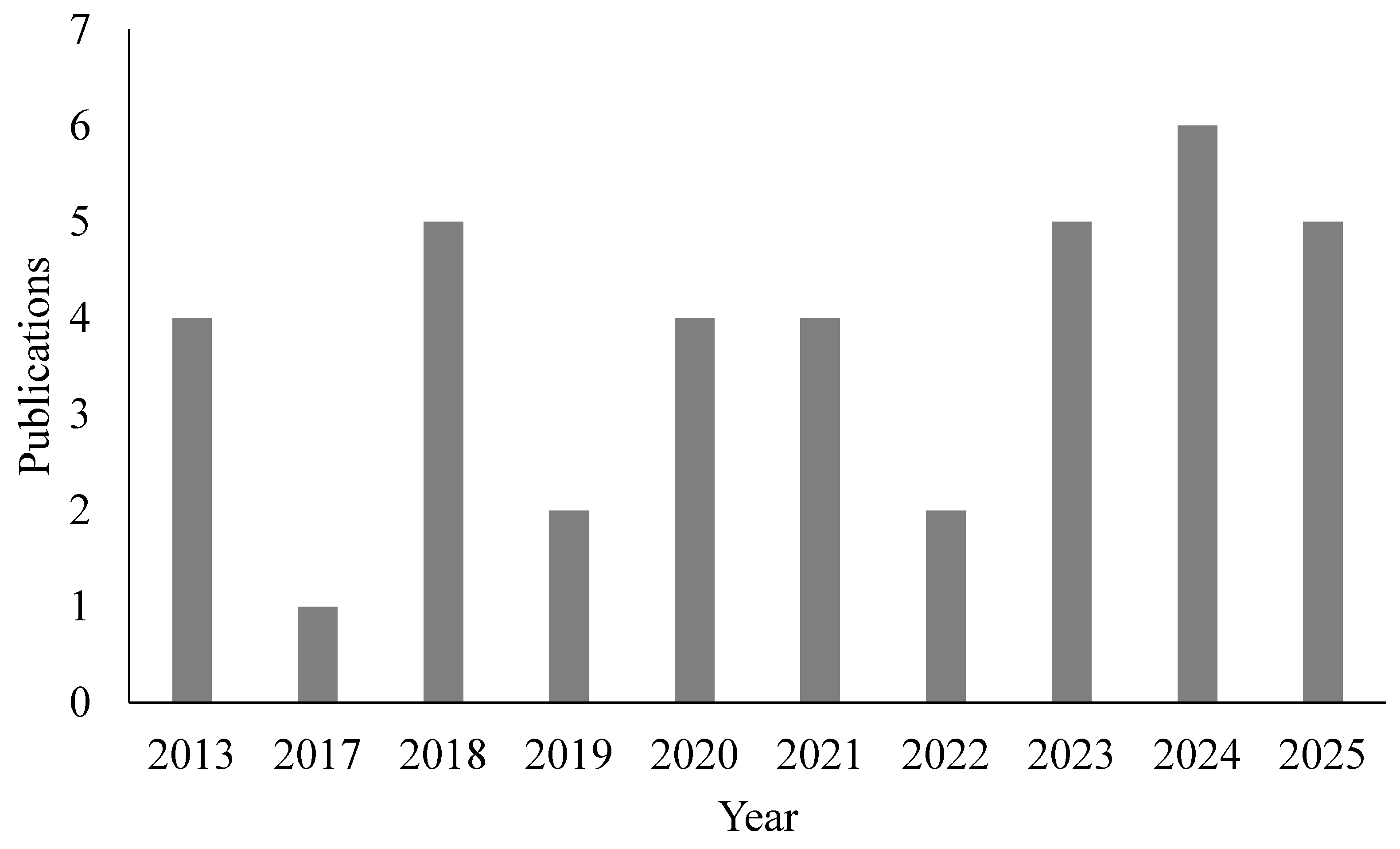

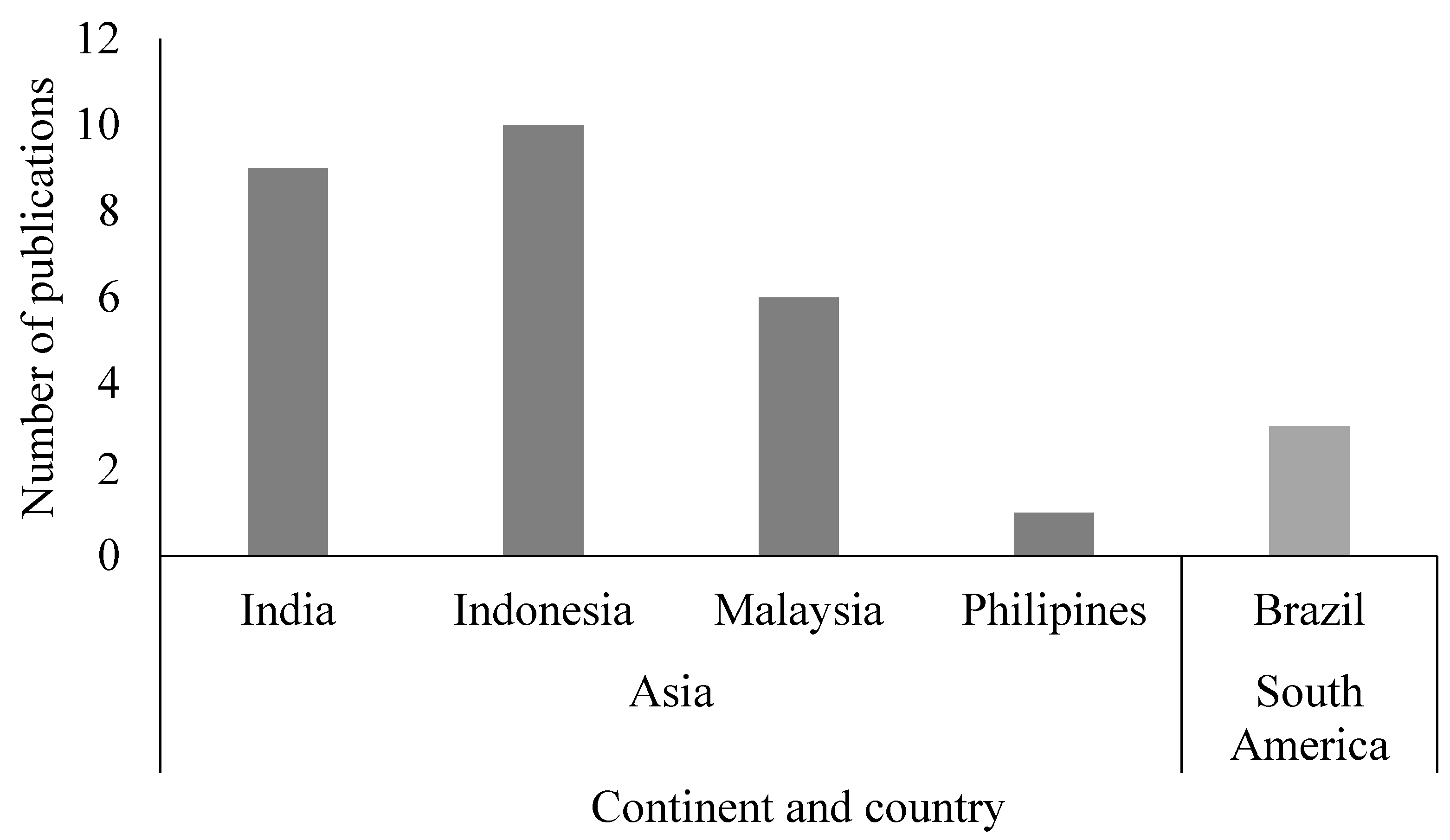

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

3.2. Health/Medicine

3.3. Human Food

3.4. General Industry

3.5. Animal Nutrition

3.6. Agriculture

4. Carrageenan Extraction

5. Gaps and Prospects

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rudke, A.R.; Andrade, C.J.; Ferreira, S.R.S. Kappaphycus alvarezii Macroalgae: An Unexplored and Valuable Biomass for Green Biorefinery Conversion. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 103, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2018; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/87109e17-2bb7-4d20-874b-160ac0a2b131 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Solorzano-Chavez, E.G.; Paz-Cedeno, F.R.; Ezequiel de Oliveira, L.; Gelli, V.C.; Monti, R.; Conceição de Oliveira, S.; Masarin, F. Evaluation of the Kappaphycus alvarezii Growth under Different Environmental Conditions and Efficiency of the Enzymatic Hydrolysis of the Residue Generated in the Carrageenan Processing. Biomass Bioenergy 2019, 127, 105254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.D.; Flórez-Fernández, N.; Domínguez, H. Integral Utilization of Red Seaweed for Bioactive Production. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chevenier, A.; Jouanneau, D.; Ficko-Blean, E. Carrageenan Biosynthesis in Red Algae: A Review. Cell Surf. 2023, 9, 100097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, A.C.; Amaro, H.M.; Sousa-Pinto, I.; Malcata, F.X. Algal Spent Biomass—A Pool of Applications. In Biofuels from Algae; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 397–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, M.; Allahgholi, L.; Sardari, R.R.R.; Hreggviðsson, G.O.; Nordberg Karlsson, E. Extraction and Modification of Macroalgal Polysaccharides for Current and Next-Generation Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudhakar, M.P.; Bargavi, P. Fabrication and Characterization of Stimuli Responsive Scaffold/Bio-Membrane Using Novel Carrageenan Biopolymer for Biomedical Applications. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2023, 21, 101344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heriyanto, H.; Kustiningsih, I.; Sari, D.K. The effect of temperature and time of extraction on the quality of Semi Refined Carrageenan (SRC). MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 154, 01034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saade, E.; Fadhilah, S.H.; Kalsum, U.; Usman, N.G. The effect of various processed seaweed, Kappaphycus alvarezii products as gel diet thickener on the utilization of nutrition in Rabbitfish, Siganus guttatus cultivation in the floating net cage. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 564, 012050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupert, R.; Rodrigues, K.F.; Thien, V.Y.; Yong, W.T.L. Carrageenan from Kappaphycus alvarezii (Rhodophyta, Solieriaceae): Metabolism, Structure, Production, and Application. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 859635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vairappan, C.S. Probiotic fortified seaweed silage as feed supplement in marine hatcheries. In Advances in Probiotics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periyasamy, C.; Subba Rao, P.V.; Anantharaman, P. Harvest Optimization to Assess Sustainable Growth and Carrageenan Yield of Cultivated Kappaphycus alvarezii (Doty) Doty in Indian Waters. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019, 31, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, P.N.; Gor, A. Natural Polysaccharide-Based Hydrogels and Nanomaterials. In Handbook of Nanomaterials for Industrial Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 36–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A.; Meher, M.K.; Gulati, K.; Poluri, K.M. Fabrication of biopolymer-based organs and tissues using 3D bioprinting. In 3D Printing Technology in Nanomedicine; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloareg, B.; Badis, Y.; Cock, J.M.; Michel, G. Role and Evolution of the Extracellular Matrix in the Acquisition of Complex Multicellularity in Eukaryotes: A Macroalgal Perspective. Genes 2021, 12, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rode, M.P.; Batti Angulski, A.B.; Gomes, F.A.; da Silva, M.M.; Jeremias, T.S.; de Carvalho, R.G.; Iucif Vieira, D.G.; Oliveira, L.F.C.; Fernandes Maia, L.; Trentin, A.G.; et al. Carrageenan Hydrogel as a Scaffold for Skin-Derived Multipotent Stromal Cells Delivery. J. Biomater. Appl. 2018, 33, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignesh, T.S.; Suja, C.P.; Geetha, S. Fabrication of tissue engineering scaffolds using marine bioactive materials for diverse applications. J. Coast. Res. 2019, 86, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, A.R.; Shanmugam, M. Isolation of Phycoerythrin from Kappaphycus alvarezii: A Potential Natural Colourant in Ice Cream. J. Appl. Phycol. 2020, 32, 4221–4233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, A.R.; Shanmugam, M.; Bhat, R. Producing Novel Edible Films from Semi Refined Carrageenan (SRC) and Ulvan Polysaccharides for Potential Food Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 112, 1164–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalvina, A.; De Ramon N’Yeurt, A.; Lako, J.; Piovano, S. Effects of Selected Environmental Conditions on Growth and Carrageenan Quality of Laboratory-Cultured Kappaphycus alvarezii (Rhodophyta) in Fiji, South Pacific. J. Appl. Phycol. 2022, 34, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, H.M. Potential of Carrageenans in Foods and Medical Applications. Glob. Health Manag. J. 2018, 2, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L. Seaweeds as Source of Bioactive Substances and Skin Care Therapy—Cosmeceuticals, Algotheraphy, and Thalassotherapy. Cosmetics 2018, 5, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hans, N.; Gupta, S.; Pattnaik, F.; Patel, A.K.; Naik, S.; Malik, A. Valorization of Kappaphycus alvarezii through Extraction of High-Value Compounds Employing Green Approaches and Assessment of the Therapeutic Potential of κ-Carrageenan. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 250, 126230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johari, N.S.C.; Aizad, S.; Zubairi, S.I. Efficacy Study of Carrageenan as an Alternative Infused Material (Filler) in Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) Porous 3D Scaffold. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2017, 2017, 5029194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamatsu, J.; Kim, S.; Ayarza, J.; Ramírez, E.; Elgegren, M.; Aguilar, R. Eco-Friendly Modification of Earthen Construction with Carrageenan: Water Durability and Mechanical Assessment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 139, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, S.D.; Nagarathnam, R. Sulfated Polysaccharide from Kappaphycus alvarezii (Doty) Doty Ex P.C. Silva Primes Defense Responses against Anthracnose Disease of Capsicum Annuum Linn. Algal Res. 2018, 32, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, S.D.; Govindan, M.; Muthamilarasan, M.; Nagarathnam, R. A Sulfated Polysaccharide κ-Carrageenan Induced Antioxidant Defense and Proteomic Changes in Chloroplast against Leaf Spot Disease of Tomato. J. Appl. Phycol. 2021, 33, 2667–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurani, W.; Anwar, Y.; Batubara, I.; Arung, E.T.; Fatriasari, W. Kappaphycus alvarezii as a Renewable Source of Kappa-Carrageenan and Other Cosmetic Ingredients. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 260, 129458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.; Azevedo, G.Z.; Schmitz, C.; Lima, G.P.P.; Maraschin, M. The importance of the CAPES scientific database for the Brazilian and world research. Rev. Bras. Pós-Grad. 2025, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumah, Y.U.; Tumbokon, B.L.M.; Serrano, A.E., Jr. Effects of Dietary κ-Carrageenan on Growth and Resistance to Acute Salinity Stress in the Black Tiger Shrimp Penaeus Monodon Post Larvae. Isr. J. Aquac.-Bamidgeh 2020, 72, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarman, K.; Sadi, U.; Santoso, J.; Hardjito, L. Carrageenan and its enzymatic extraction. In Encyclopedia of Marine Biotechnology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 147–159. [Google Scholar]

- Tabacof, A.; Calado, V.; Pereira, N., Jr. Lactic Acid Fermentation of Carrageenan Hydrolysates from the Macroalga Kappaphycus alvarezii: Evaluating Different Bioreactor Operation Modes. Polysaccharides 2023, 4, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalitnik, A.A.; Byankina Barabanova, A.O.; Nagorskaya, V.P.; Reunov, A.V.; Glazunov, V.P.; Solov’eva, T.F.; Yermak, I.M. Low Molecular Weight Derivatives of Different Carrageenan Types and Their Antiviral Activity. J. Appl. Phycol. 2013, 25, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjivkumar, M.; Chandran, M.N.; Suganya, A.M.; Immanuel, G. Investigation on Bio-Properties and in-Vivo Antioxidant Potential of Carrageenans against Alloxan Induced Oxidative Stress in Wistar Albino Rats. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 151, 650–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azhar, F.; Mukhlis, A.; Lestari, D.P.; Marzuki, M. Application of Kappa-Carrageenan as Immunostimulant Agent in Non-Specific Defense System of Vannamei Shrimp. 2023. Available online: https://bioflux.com.ro/docs/2023.616-624.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Amruth, P.; Rosemol, J.M.; Joy, J.M.; Visnuvinayagam, S.; Remya, S.; Mathew, S. Development of κ-Carrageenan-Based Transparent and Absorbent Biodegradable Films for Wound Dressing Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 137084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, R.Z.L.; Teo, S.S.; Yeong, H.Y.; Yeap, S.P.; Kee, P.E.; Lam, S.S.; Lan, J.C.-W.; Ng, H.S. Production and Characterization of Seaweed-Based Bioplastics Incorporated with Chitin from Ramshorn Snails. Syst. Microbiol. Biomanuf 2024, 4, 1096–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariot, L.V.; Bolívar, N.; Coelho, J.D.R.; Goncalves, P.; Colombo, S.M.; Nascimento, F.V.; Schleder, D.D.; Hayashi, L. Diets Supplemented with Carrageenan Increase the Resistance of the Pacific White Shrimp to WSSV without Changing Its Growth Performance Parameters. Aquaculture 2021, 545, 737172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distantina, S.; Rochmadi, R.; Fahrurrozi, M.; Wiratni, W. Preparation and Characterization of Glutaraldehyde-Crosslinked Kappa Carrageenan Hydrogel. Eng. J. 2013, 17, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praseptiangga, D.; Maimuni, B.H.; Manuhara, G.J.; Muhammad, D.R.A. Mechanical and Barrier Properties of Semi Refined kappa Carrageenan-based Composite Edible Film and its Application on Minimally Processed Chicken Breast Fillet. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 333, 012086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryani, I.; Sari, D.I.P.; Astutik, D.M.; Abdillah, A.A. Kappa and iota Carrageenan Combination of Kappaphycus alvarezii and Eucheuma spinosum as a Gelatin Substitute in Ice Cream Raw Material Product. IOP Conf. Ser Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 236, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.S.; Vantharam Venkata, H.G.R.; Raju, M.V.; Rama Rao, S.V.; Nori, S.S.; Suryanarayan, S.; Kumar, V.; Perveen, Z.; Prasad, C.S. Dietary Supplementation of Extracts of Red Sea Weed (Kappaphycus alvarezii) Improves Growth, Intestinal Morphology, Expression of Intestinal Genes and Immune Responses in Broiler Chickens. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 997–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widyastuti, S.; Handayani, B.R.; Werdiningsih, W.; Ariyana, M.D.; Rahayu, N. Report on the Use of λ-and κ-Carrageenans Extracted from Seaweeds in Improving Bread Quality. 2021. Available online: https://www.akademisains.gov.my/asmsj/article/repo (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Praseptiangga, D. Mechanical and barrier properties of refined kappa carrageenan-based edible film incorporating palmitic acid and zein. Asia Pac. J. Sci. Technol. 2022, 27, APST-27-04-07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhewang, I.B.; Yudiati, E.; Alghazeer, R. Supplementation of Carrageenan (Kappaphycus alvarezii) for Shrimp Diet to Improve Immune Response and Gene Expression of White Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). J. Mar. Sci. 2023, 28, 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Kurniawan, D.W.; Rasyid, K.A.; Santosa, R.A. Sunarto Extraction and Characterization of Carrageenan from Seaweed (Kappaphycus alvarezii) Produced by South Lampung Indonesia Farmers and Utilization as a Tablet Binder Using Metformin as a Drug Model. Iraqi J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 33, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfatah, T.; Mistar, E.M.; Aswita, D.; Jaber, M.; Surya, I. Structural and Chemical Properties of Kappa-Carrageenan Extracted from Macroalgae by Deep Eutectic Solvents and Sustainable Biopolymer Films Produced Thereof. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2025, 30, 102120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekar, V.; Karthickumar, P.; Rose, A.H.R.; Manimmehalai, N.; Subhasri, D. Development and Characterization of Biodegradable Film from Marine Red Seaweed (Kappaphycus alvarezii). Pigment Resin Technol. 2023, 52, 478–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, I.; Baskaralingam, V.; Elumalai, P. Extraction and Characterization of Antibacterial Marine Polysaccharide K-Carrageenan from Kappaphycus alvarezii against Multidrug-Resistant Wound Associated Bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 37446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarangam, B.; Prabhu, D.; Raja, R.; Sangeetha, P.; Jayappriyan, K.R.; Kandasamy, S.; Narayanan, M. Experimental and in Silico Approaches to Identify a Sustainable Source of Bioplastics from Seaweeds. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2025, 15, 22889–22899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariffin, S.H.Z.; Yeen, W.W.; Wahab, R.M.A.; Ramli, N.; Senafi, S. Carrageenan and Seaweed Powder Anticytotoxicity and Antioral Bacterial Activity. Open Conf. Proc. J. 2013, 4, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjamsiah; Ramli, N.; Daik, R.; Yarmo, M.A.; Ajdari, Z. Nutritional Study of Kapparazii powderTM as a Food Ingredient. J. Appl. Phycol. 2014, 26, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, H.A.; Mohamad, H.C.I.C.; Khairunnisa, A.R.; Owolabi, F.A.T.; Asniza, M.; Rizal, S.; Fazita, M.R.N.; Paridah, M.T. Development and Characterization of Bamboo Fiber Reinforced Biopolymer Films. Mat. Res. Expr. 2018, 5, 085309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, X.Y.; Khalid, M.; Raju, G.; Gew, L.T.; Yow, Y.Y. Synergistic Effects of Starch and Carrageenan from Kappaphycus alvarezii in Composite Film Formation: Physicochemical and Degradable Properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 135205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffar, S.S.; Saallah, S.; Misson, M.; Siddiquee, S.; Roslan, J.; Lenggoro, W. Development and Characterization of Carrageenan/Nanocellulose/Silver Nanoparticles Bionanocomposite Film from Kappaphycus alvarezii Seaweed for Food Packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 311, 143922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcantara, G.U.; Rocha, L.P.; de Castilhos, M.B.M.; Costa, G.H.G. Preparation of Red Seaweed Extract for Use as a Flocculant Agent in Sugarcane Juice and Comparison between Two Experimental Designs. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 205, 117530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudke, A.R.; de Andrade, C.J.; Ferreira, S.R.S. High-Purity κ-Carrageenan from Kappaphycus alvarezii Algae for Aerogel Production by Supercritical CO2 Drying. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2025, 217, 106454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarman, K.; Supinah, P.; Dewanti, E.W.; Santoso, J.; Nurjanah, N. Characteristics of Carrageenan from Seaweed Hydrolysis Using Marine Fungi as Hard-Shell Capsule Material: Karakteristik karagenan dari hidrolisis rumput laut menggunakan kapang laut sebagai bahan cangkang kapsul keras. J. Pengolah. Has. Perikan. Indones. 2024, 27, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neamtu, B.; Barbu, A.; Negrea, M.O.; Berghea-Neamțu, C.Ș.; Popescu, D.; Zăhan, M.; Mireșan, V. Carrageenan-Based Compounds as Wound Healing Materials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, A.; Esmkhani, M.; Zallaghi, M.; Nezafat, Z.; Javanshir, S. Biomedical and Environmental Applications of Carrageenan-Based Hydrogels: A Review. J. Polym. Environ. 2023, 31, 1679–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Chen, S.; Su, J.; Zhu, M.; Zhou, M.; Chen, T.; Han, Y. Recent Advances in Carrageenan-Based Films for Food Packaging Applications. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1004588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.; Azevedo, G.Z.; de Souza Dutra, F.; dos Santos, B.R.; Schneider, A.R.; Oliveira, E.R.; Moura, S.; Vianello, F.; Maraschin, M.; Lima, G.P.P. Uses and Applications of the Red Seaweed Kappaphycus alvarezii: A Systematic Review. J. Appl. Phycol. 2024, 36, 3409–3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, L.; Ravi, N.; Kumar Mondal, A.; Akter, F.; Kumar, M.; Ralph, P.; Kuzhiumparambil, U. Seaweed-Based Polysaccharides—Review of Extraction, Characterization, and Bioplastic Application. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 5790–5823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, N.A.; Kamarol Zani, N.A.A.; Ramli, N.A.; Mohd Azman, N.A.; Adam, F.; Abu Bakar, N.F.; Rehan, M. A Mechanistic Study of the Synthesis of Sustainable Carrageenan-Polylactic Acid Biocomposite. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2024, 49, 8115–8129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasempour, A.; Naderi Allaf, M.R.; Charoghdoozi, K.; Dehghan, H.; Mahmoodabadi, S.; Bazrgaran, A.; Savoji, H.; Sedighi, M. Stimuli-Responsive Carrageenan-Based Biomaterials for Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 291, 138920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadzadeh, N.; Ghorbanpour, M.; Sayyah, A. Effects of Filler Type and Content on Mechanical, Thermal, and Physical Properties of Carrageenan Biocomposite Films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, L.; Bak, U.G.; Hansen, S.C.B.; Gregersen, O.; Harmsen, P.; Karlsson, E.N.; Meyer, A.; Mikkelsen, M.D.; Van Den Broek, L.; Hreggviðsson, G.Ó. Opportunities for seaweed biorefinery. In Sustainable Seaweed Technologies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sudhakar, K.; Mamat, R.; Samykano, M.; Azmi, W.H.; Ishak, W.F.W.; Yusaf, T. An Overview of Marine Macroalgae as Bioresource. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 91, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, A.W.; Horne, C.H. Toxicity of Various Carrageenans in the Mouse. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 1976, 57, 455–459. [Google Scholar]

- Tobacman, J.K. Review of Harmful Gastrointestinal Effects of Carrageenan in Animal Experiments. Environ. Health Perspect. 2001, 109, 983–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Du, Y.; Liu, H.; Ding, H.; Zhang, W.; Li, Z.; Shi, B. Maternal Supplementation with Konjac Glucomannan and κ-Carrageenan Promotes Sow Performance and Benefits the Gut Barrier in Offspring. Anim. Nutr. 2024, 19, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvakumar, P.; Manjunath, T.C. Food Technology Innovation. In Em Advances in Marketing, Customer Relationship Management, and E-Services; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 215–242. ISBN 9798369385425. [Google Scholar]

- Umhaw, G.P.; Naval, R.C.; Dolojan, F.M.; Abella, M.E.S.; Hizon, M.G.S.; Mabborang, S.A. Effects of Radiation-Modified kappa-Carrageenan Supplementation in Corn (Zea mays L.). J. Sci. Food and Agric. 2020, 100, 5246–5253. [Google Scholar]

- Lechat, H.; Amat, M.; Mazoyer, J.; Buléon, A.; Lahaye, M. Structure and Distribution of Glucomannan and Sulfated Glucan in the Cell Walls of the Red Alga Kappaphycus alvarezii (Gigartinales, Rhodophyta). J. Phycol. 2000, 36, 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirtawijaya, G.; Meinita, M.D.N.; Marhaeni, B.; Haque, M.N.; Moon, I.S.; Hong, Y.-K. Neurotrophic Activity of the Carrageenophyte Kappaphycus alvarezii Cultivated at Different Depths and for Different Growth Periods in Various Areas of Indonesia. Evid. Based. Complement. Alternat. Med. 2018, 2018, 1098076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battacharyya, D.; Babgohari, M.Z.; Rathor, P.; Prithiviraj, B. Seaweed Extracts as Biostimulants in Horticulture. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Song, J.; Li, X.; Li, N.; Dai, J. Immunomodulation and Antitumor Activity of Kappa-Carrageenan Oligosaccharides. Cancer Lett. 2006, 243, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.S.; Borza, T.; Critchley, A.T.; Prithiviraj, B. Carrageenans from Red Seaweeds as Promoters of Growth and Elicitors of Defense Response in Plants. Front. Mar. Sci. 2016, 3, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadarajan, S.A.; Ramli, N.; Ariff, A.; Said, M.; Yasir, S.M.; Ariff, B.; Wilhelmus, M. Development of high yielding carragenan extraction method from Eucheuma cotonii using cellulase and Aspergillus niger. In Proceedings of the Prosiding Seminar Kimia Bersama UKM-ITB VIII9, Bangi, Malaysia, 9–11 June 2009; pp. 461–469. [Google Scholar]

- Hamamouche, K.; Elhadj, Z.; Khattabi, L.; Zahnit, W.; Djemoui, B.; Kharoubi, O.; Boussebaa, W.; Bouderballa, M.; El Moustapha Kallouche, M.; Attia, S.M.; et al. Impact of Ultrasound- and Microwave-Assisted Extraction on Bioactive Compounds and Biological Activities of Jania Rubens and Sargassum Muticum. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Chen, L.; Liu, X.; Li, D.; Ye, N.; Wang, L. Thermal Behavior of Carrageenan: Kinetic and Characteristic Studies. Int. J. Green Energy 2012, 9, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssouf, L.; Lallemand, L.; Giraud, P.; Soulé, F.; Bhaw-Luximon, A.; Meilhac, O.; D’Hellencourt, C.L.; Jhurry, D.; Couprie, J. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction and Structural Characterization by NMR of Alginates and Carrageenans from Seaweeds. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 166, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.D.; Flórez-Fernández, N.; Dominguez, H. Ultrasound-Assisted Water Extraction of Mastocarpus stellatus Carrageenan with Adequate Mechanical and Antiproliferative Properties. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tako, M. The Principle of Polysaccharide Gels. Adv. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2015, 06, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhein-Knudsen, N.; Ale, M.T.; Meyer, A.S. Seaweed Hydrocolloid Production: An Update on Enzyme Assisted Extraction and Modification Technologies. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 3340–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedayu, B.B.; Cran, M.J.; Bigger, S.W. Reinforcement of Refined and Semi-Refined Carrageenan Film with Nanocellulose. Polymers 2020, 12, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Zhang, K.; Wang, L.; Han, J.; Wang, Y.; Xue, Z.; Xia, Y. High-Strength Carrageenan Fibers with Compactly Packed Chain Structure Induced by Combination of Ba2+ and Ethanol. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 236, 116057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, L.; de Souza, M.C.; Bonafe, E.G.; Martins, A.F.; Monteiro, J.P. Optimized Incorporation of Silver Nanoparticles onto Cotton Fabric Using K-Carrageenan Coatings for Enhanced Antimicrobial Properties. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024, 7, 6908–6918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Qiao, C.; Geng, C.; Liu, X.; Zeng, Y.; Chang, Q.; Zhao, G.; Xue, Z. Preparation of Carrageenan Fibers Promoted by Hydrogen Bonding in a NaCl Coagulation Bath. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 347, 122792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Xiao, Y.; Fu, G.; Feng, C.; Hu, J.; Haegeman, W.; Liu, H. Calcareous Silt Earthen Construction Using Biopolymer Reinforcement. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 72, 106571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, D.; Venkatachalam, C.D.; Sundaravadivelu, K.; Rajan, S.; Vigneshwaran, V.; Gupta, R.K. Sustainable Applications of Carrageenan as a Next-Generation Biopolymer in Intelligent and Active Food Packaging. Sustain. Food Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, F.; E-Aimen, Z.; Ahmad, R.; Mir, S.; Awwad, N.S.; Ibrahium, H.A. Carrageenan: Structure, Properties and Applications with Special Emphasis on Food Science. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 22035–22062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, E.; Colbert, D. Ocean Plastics: Extraction, Characterization and Utilization of Macroalgae Biopolymers for Packaging Applications. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Lovatelli, A.; Aguilar-Manjarrez, J.; Cornish, L.; Dabbadie, L.; Desrochers, A.; Diffey, S.; Garrido Gamarro, E.; Geehan, J.; Hurtado, A.; et al. Seaweeds and Microalgae: An Overview for Unlocking Their Potential in Global Aquaculture Development; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oort, P.A.J.; Julianto, B.; Latama, G.; Siradjuddin, I.; Rukminasari, N.; Walyandra, Z.Z.; Ibrahim, I.A.; Verhagen, A.; van der Werf, A.K. Yield Determinants of Kappaphycus alvarezii Seaweed in South Sulawesi, Indonesia. J. Appl. Phycol. 2025, 37, 1153–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantri, V.A.; Munisamy, S.; Kambey, C.S.B. Biosecurity Aspects in Commercial Kappaphycus alvarezii Farming Industry: An India Case Study. Aquac. Rep. 2024, 35, 101930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.-L.; Poong, S.-W.; Tan, J.; Brakel, J.; Gachon, C.; Brodie, J.; Sade, A.; Lim, P.-E. Assessment of Genetic Diversity within Eucheumatoid Cultivars in East Sabah, Malaysia. J. Appl. Phycol. 2022, 34, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumilag, R.V.; Crisostomo, B.A.; Aguinaldo, Z.Z.A.; Hinaloc, L.A.R.; Liao, L.M.; Roa-Quiaoit, H.A.; Dangan-Galon, F.; Zuccarello, G.C.; Guillemin, M.L.; Brodie, J.; et al. The Diversity of Eucheumatoid Seaweed Cultivars in the Philippines. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2023, 31, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, A.Q.; Neish, I.C.; Critchley, A.T. Developments in Production Technology of Kappaphycus in the Philippines: More than Four Decades of Farming. J. Appl. Phycol. 2015, 27, 1945–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazil. Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis. Instrução Normativa 1, de 21 de Janeiro de 2020. IBAMA; 2020. Available online: https://www.ibama.gov.br/component/legislacao/?view=legislacao&legislacao=138683 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Hayashi, L.; Santos, A.A.; Ventura, T.F.B.; Landuci, F.S.; Gelli, V.C.; Castelar, B. Kappaphycus alvarezii Farming in Brazil: A Brief Summary and Current Trends. In Developments in Applied Phycology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 113–120. [Google Scholar]

| Area | Nº | Target Effect | Matrix Used | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scaffolds | 1 | Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) (PHBV) porous 3D scaffolds with carrageenan to assess stability and cellular acceptability | PHBV and k-carrageenan of K. alvarezii | The 4% carrageenan-infused scaffold emerged as the best candidate for tissue engineering applications and 3D cell culture models, balancing degradation kinetics with sustained structural support | Johari et al. [25] |

| 2 | Enhanced wound healing, including improved collagen deposition, neovascularization, and reduced wound size | Carrageenan hydrogel encapsulating mesenchymal stromal cells (eCH+MSC) | The eCH+MSC treatment showed better wound closure, increased collagen deposition, and higher vessel density, indicating greater healing efficacy | Rode et al. [17] | |

| 3 | Molluscan nacre and using natural polymers, to evaluate its structure, composition, and potential biomedical applications | k-carrageenan of K. alvarezii, collagen of Sepia lycidas, and chitosan of shrimp shell | The scaffolds presented broad potential for tissue engineering applications, including 3D cell culture models for the production of edible meat, tissues, and organs | Vignesh et al. [18] | |

| 4 | Aerogels are produced from high-purity α-carrageenan | Commercial carrageenan (CC) and high-purity carrageenan (HP) of K. alvarezii | The use of high-purity carrageenan results in materials exhibiting superior firmness and greater surface area compared to those produced via commercial carrageenan methods or cryogels | Rudke et al. [59] | |

| Antimicrobial | 1 | The anticytotoxic activity and oral antibacterial activity of crude κ-carrageenan powder, ι-carrageenan, and kappa seaweed | Crude powder of κ-carrageenan, ι-carrageenan, kappa seaweed of K. alvarezii and Eucheuma spinosum and human cells (HepG2, Caco-2) cells | These types of carrageenan and the crude powder of kappa seaweed were non-toxic to HepG2 and Caco-2 cells | Ariffin et al. [53] |

| 2 | The antiviral activity against tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) | Derivatives of κ- and κ/β-carrageenans, and Nicotiana tabacum L. leaves (Samsun strain) | High molecular weight carrageenan derivatives proved generally more effective and retained antiviral capacity against tobacco mosaic virus | Kalitnik et al. [35] | |

| 3 | κ-Carrageenan exhibits significant antibacterial and anti-biofilm properties wound associated bacteria | κ-Carrageenan from K. alvareziin nutrient broth and red blood cells (RBCs) | κ-Carrageenan attacks and eliminate multidrug-resistant wound-associated bacteria by disrupting cellular membranes, inhibiting biofilm formation, and inducing oxidative stress, while demonstrating no cytotoxicity toward human red blood cells | Ramachandran et al. [51] | |

| Blinding agent | 1 | Carrageenan from K. alvarezii demonstrated its potential as a binder for metformin tablets | Metformin HCl, carrageenan extracted from K alvarezii, and carbopol | Carrageenan demonstrated its potential as a binder for metformin tablets, suggesting the need for further optimization to enhance degradation performance | Kurniawan et al. [48] |

| Therapeutic agent | 2 | In vivo antioxidant potential of native carrageenan against alloxan-induced oxidative stress in Wistar albino rats | Carrageenan from K. alvarezii, commercial carrageenan and Wistar albino rats | Native carrageenan from K. alvarezii exhibits significant antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticoagulant properties, positioning it as a promising therapeutic agent for oxidative stress and diabetes-related complications, with superior pharmacological activities | Sanjivkumar et al. [36] |

| Encapsulating agent | 1 | Potential of carrageenan as a material for hard capsules through hydrolysis of marine fungi, demonstrating its characteristics | Carrageenan from K. alvarezii and marine fungus Enhalus sp. | Carrageenan was successfully extracted via marine fungi hydrolysis, showing strong potential for hard capsules. Semi-refined carrageenan displayed promising physicochemical properties and suitable disintegration times | Tarman et al. [60] |

| Wound dressing | 1 | Carrageenan, combined with polyvinylpyrrolidone and glycerol in the development of biodegradable wound dressing applications | Carrageenan from K. alvarezii, polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), and glycerol (GLY), methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli, and Wistar rats | The films demonstrated excellent absorption, transparency, mechanical strength, antibacterial activity, and biocompatibility, making them a promising solution for advanced wound treatment applications | Amruth et al. [38] |

| Area | Nº | Target Effect | Matrix Used | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edible films | 1 | Semi-refined carrageenan (SRC), ulvan, and their combination, in edible films to assess mechanical, and functional properties | SRC, ulvan polysaccharide, and a combination of both | The combined film showed higher mechanical strength and stability. The films demonstrated significant antioxidant activities, including hydroxyl radical scavenging, metal ion chelating, and reducing power | Ganesan et al. [20] |

| 2 | Semi-refined carrageenan (SRC) based edible films as a coating for chicken breast filets | SRC and bio-nanocomposite film | Mechanical strength, barrier properties, and suitability for food preservation indicate the potential of these films to extend the shelf life and maintain the quality of chicken breast filet | Praseptiangga et al. [42] | |

| 3 | algal polysaccharides like carrageenan for biodegradability and barrier functions. Bamboo fiber enhances mechanical strength and sustainability | Carrageenan from K. alvarezii, bamboo fiber, and glycerol | Films composed of biopolymers derived from red marine algae and reinforced with bamboo fiber serve as packaging films in the food industry | Abdul et al. [55] | |

| 4 | Different concentrations of palmitic acid and zein affect the mechanical properties and water vapor barrier of edible films refined based on kappa-carrageenan | Refined kappa-carrageenan powder, palmitic acid, and zein | The incorporation of palmitic acid and zein into refined kappa-carrageenan-based films shows potential for developing food packaging materials with enhanced moisture barrier properties, although it may affect mechanical strength | Praseptiangga et al. [46] | |

| 5 | Carrageenan and bionanocomposites enable the development of advanced films for food packaging applications | Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), nanocellulose from residual biomass, and carrageenan from K. alvarezii | Bionanocomposite films of carrageenan/nanocellulose/silver nanoparticles using marine algae demonstrated their potential as functional and sustainable materials for food packaging due to their mechanical, barrier, thermal, and antimicrobial properties | Jaffar et al. [57] | |

| Ice cream | 1 | Combination of kappa and iota carrageenan blend as a gelatin substitute in ice cream | Carrageenan flour of K. alvarezii and E. spinosum | The addition of a kappa and iota carrageenan blend in ice cream manufacture can effectively serve as a substitute for gelatin. Therefore, it represents a promising innovative emulsifier for ice cream production | Suryani et al. [43] |

| 2 | Extraction of phycoerythrin (PE) and encapsulate it with carrageenan (PE-Kc) and guar gum (PE-Gg) to assess stability and functionality in ice cream | PE, PE-Kc and PE-Gg | Microencapsulation with PE-Kc and PE-Gg enhanced the stability of PE in ice cream, maintaining color intensity for 90 days. These matrices also influenced the rheological, sensory, and functional properties of the ice cream | Ganesan et al. [19] | |

| Food additive agent | 1 | Potential of Kapparazii powder as a healthy ingredient for food industry applications | K. alvarezii powder and L929 mouse fibroblast cells | Kapparazii powder demonstrated its potential as a valuable and nutrient-rich hydrocolloid for the food industry, with favorable physicochemical properties and no cytotoxic effects | Sjamsiah et al. [54] |

| 2 | Potential of λ- and α-carrageenans extracted from red algae as natural bread improvers | Basic bread formula and K. alvarezii carrageenans | λ- and α-carrageenans from red algae can serve as effective natural bread improvers, significantly increasing bread volume, improving crumb texture and structure, and extending shelf life by delaying moisture loss and maintaining elasticity, particularly at lower concentrations | Widyastuti et al. [45] | |

| Flocculating agent | 1 | Natural flocculant derived from red algae, specifically targeting carrageenan extraction, for use in sugarcane juice treatment | Sugarcane juice extracted from the CTC072361 variety and samples of red from algae K. alvarezii | Potential of red algae extract as a natural bioflocculant for clarifying sugarcane juice, offering a sustainable alternative to synthetic flocculants | Alcantra et al. [58] |

| Area | Nº | Target Effect | Matrix Used | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomaterials | 1 | Production of Kappaphycus-based (KBF) and carrageenan-based (CBF) bio-nanocomposite films enhanced with zinc oxide (ZnO), cupric oxide (CuO), and silicon dioxide (SiO2) | CBF and KBF matrices with ZnO, CuO, SiO2 nanoparticles | The KBF proves to be a viable alternative, particularly due to its superior antimicrobial activity and enhanced barrier properties | Sudhakar et al. [8] |

| 2 | Development of biodegradable films for food packaging and commercial applications, leveraging optimized mechanical strength, water vapor permeability, and biodegradability | Carrageenan extracted via alcohol method from K.s alvarezii red seaweed combined with rice starch | Mechanical properties and water vapor permeability improved with higher concentrations; optimal film achieved at low carrageenan and high rice starch, showing broad commercial potential | Rajasekar et al. [50] | |

| 3 | Carrageenan combined with starch and glycerol in the development of films for edible food packaging, disposable utensils, and agricultural films | Carrageenan from K. alvarezii, tapioca starch, and glycerol | Films made from starch and carrageenan exhibit impressive thermal, mechanical, and biodegradability properties. These characteristics suggest their viability as substitutes for conventional plastics | Yap et al. [56] | |

| 4 | Feasibility of producing sustainable bioplastics from seaweed and snail-derived chitin as an eco-friendly alternative to petroleum-based plastics | Starch and carrageenan from K. alvarezii and chitin from the shells of ramshorn snails Planorbarius corneus | Carrageenan effectively mediated starch-chitin interactions in the composite bioplastic, resulting in a denser network structure. Chitin and carrageenan incorporation significantly improved tensile strength and water resistance by mitigating hydrophilicity and filling microstructural voids | Leong et al. [39] | |

| 5 | Development biodegradable and biocompatible materials with tailored mechanical properties suitable for food packaging and biomedical fields | Carrageenan (extracted from K. alvarezii), sodium alginate (from Sargassum wightii), and agar (from Gracilaria crassa and Gelidiella acerosa) | The carrageenan, sodium alginate, and corn starch bioplastic exhibited tensile strength (TS) and elongation at break, serving as a viable ecological alternative to conventional plastics with potential for food packaging and biomedical applications due to its biocompatibility and degradability | Sarangam et al. [52] | |

| 6 | Manufactures biopolymer films to serve as an eco-friendly alternative to conventional petroleum-derived plastics for food packaging applications | Extracted kappa-carrageenan and glycerol as a plasticizing agent | Films produced with the KCG extract demonstrated superior tensile strength and greater thermal stability, showing high potential as sustainable marine biomaterials for advanced industrial applications | Alfatah et al. [49] | |

| Bioproduct | 1 | Development film immersion and thermal curing while analyzing how the concentration of the crosslinking agent affects the hydrogel’s properties | kappa carrageenan from K alvarezii ang glutaraldehyde | It is possible to successfully produce a chemically crosslinked kappa-carrageenan hydrogel with glutaraldehyde through a film immersion method and thermal curing | Distantina et al. [41] |

| Biorefinery | 1 | Production of lactic acid from detoxified K. alvarezii hydrolysates | K. alvarezii hydrolysates detoxified with regenerated activated charcoal, in bioreactor fermentations with Lactobacillus pentosus | The fermentation achieved a maximum lactic acid concentration in extended fed-batch mode, demonstrating effective conversion of the hydrolysates into lactic acid | Tabacof et al. [34] |

| Area | Nº | Target Effect | Matrix Used | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aquaculture | 1 | Processed product of K. alvarezii as a thickening agent in a gel diet for rabbitfish | Seaweed flour, fermented seaweed flour, carrageenan flour and seaweed soft | Fermented seaweed flour is the best thickener in the gel diet for rabbitfish, as it maximizes fish nutritional quality and protein utilization efficiency | Saade et al. [10] |

| 2 | Carrageenan effect on the growth and health parameters of the Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei | Different concentration of carrageenan obtained from K. alvarezii | Low levels of carrageenan in the diet can benefit the intestinal microbiota composition and improve resistance to WSSV without negatively affecting growth or overall health status of the shrimp | Mariot et al. [40] | |

| 3 | Carrageenan supplementation in the diet affects the immune response and the expression of immune-related genes in white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei | Carrageenan flour and white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei | Diet supplementation with K. alvarezii carrageenan significantly improves innate immunity and immune gene expression in L. vannamei over a 15-day period, demonstrating its value in enhancing shrimp defense systems in aquaculture | Dhewang et al. [47] | |

| 4 | k-carrageenan as a natural immunostimulant agent to increase the immune response and survival rate of white vannamei shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei infected with the Infectious Myonecrosis Virus | White vannamei shrimp (L. vannamei), k-carrageenan flour from K. alvarezii and Infectious Myonecrosis Virus (IMNV) | The administration of this seaweed-derived compound increases hemocyte production, boosts phagocytosis, and possesses antibacterial properties that suppress the growth of Vibrio in the intestines, thereby ensuring higher survival in shrimp cultures | Azhar et al. [37] | |

| 5 | k-carrageenan as a functional ingredient with two primary purposes: to act as a growth promoter and as an immunostimulant to increase the resistance of post-larvae to acute salinity stress | Black tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon) post-larvae and refined κ-carrageenan from k. alvarezii | κ-Carrageenan exhibits dual effects as a growth promoter and immunological stimulant against environmental stress, although the highest dose provides better protection but may eliminate growth benefits due to increased dietary fiber, which can hinder nutrient absorption | Jumah et al. [32] | |

| Livestock | 1 | Evaluate effects of K. alvarezii extracts, rich in carrageenan, on broiler chicken growth, immunity, gut health, and antioxidant status | Broiler chickens (Vencobb 400), MVP1 alkaline, PBD1 aqueous K. alvarezii extracts | The aqueous PBD1 extract effectively enhances growth and immunity in broiler chickens by increasing villus width and crypt depth | Paulet al. [44] |

| Area | Nº | Target Effect | Matrix Used | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Induction of defense | 1 | κ-carrageenan, from the red seaweed K. alvarezii as a potent inducer of plant resistance against anthracnose in chili peppers | Carrageenan of K. alvarezii and chili plants | κ-carrageenan extracted from K. alvarezii is a potent inducer of plant resistance and exhibits fungistatic activity against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides | Mani et al. [27] |

| 2 | κ-carrageenan as a potent inducer of antioxidant defense and modulator of the chloroplast proteome in tomato plants against Septoria lycopersici | Carrageenan of K. alvarezii and tomato plants | Carrageenan of K. alvarezii is a potent inducer of defense in tomato plants against Septoria lycopersici. By reducing pathogen colonization, activating antioxidant responses, and modulating the chloroplast proteome to enhance stress tolerance | Mani et al. [28] | |

| Biostimulant | 1 | Evaluate efficacy of radiation-modified kappa-carrageenan as a biostimulant to improve corn growth, yield parameters, and economic returns while reducing synthetic fertilizer use. | Radiation-modified kappa-carrageenan (RMKC) from K. alvarezii and Corn plants. | RMKC at 4 L/ha increased yield by 46%, boosted corn yield and profitability, and improved ear length and plant stand count. | Umhaw et al. [75] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ovalle, L.V.C.; Schneider, A.R.; Nunes, A.; Maraschin, M. Biotechnological Potential of Carrageenan Extracted from Kappaphycus alvarezii: A Systematic Review of Industrial Applications and Sustainable Innovations. Biomass 2026, 6, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomass6010011

Ovalle LVC, Schneider AR, Nunes A, Maraschin M. Biotechnological Potential of Carrageenan Extracted from Kappaphycus alvarezii: A Systematic Review of Industrial Applications and Sustainable Innovations. Biomass. 2026; 6(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomass6010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleOvalle, Lady Viviana Camargo, Alex Ricardo Schneider, Aline Nunes, and Marcelo Maraschin. 2026. "Biotechnological Potential of Carrageenan Extracted from Kappaphycus alvarezii: A Systematic Review of Industrial Applications and Sustainable Innovations" Biomass 6, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomass6010011

APA StyleOvalle, L. V. C., Schneider, A. R., Nunes, A., & Maraschin, M. (2026). Biotechnological Potential of Carrageenan Extracted from Kappaphycus alvarezii: A Systematic Review of Industrial Applications and Sustainable Innovations. Biomass, 6(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomass6010011