1. Introduction

A straightforward way to model brains is to represent them as networks of neurons that communicate via synapses. The collective behavior of these networks is determined by the electrochemical transmission of signals between neurons at synapses [

1]. A key dynamical feature of neuron models is the presence of an action potential, which is a spike-shaped output voltage signal. The Hindmarsh–Rose (HR) model is a simplified neuron model that effectively captures the emergence of

action potentials [

2]. Additionally, the HR model can exhibit various types of oscillations, including chaotic behavior, when specific parameter values are chosen [

3].

Communication between neurons involves both electrical and chemical components. The electrical aspect describes the ion currents triggered by voltage differences across neuronal membranes. In this context, signals can move through gap junction channels in either direction in accordance with Ohm’s law. The chemical part of synaptic transmission involves the

presynaptic neuron releasing neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft. When these chemicals bind to receptors on the

postsynaptic neuron, they generate a signal that modifies the electrical properties of the postsynaptic neuron. As a result, the signal transmission is directed and subject to time-varying parameters, saturating at a constant value as the synaptic cleft becomes filled with neurotransmitters [

4].

In recent years, several circuit implementations of neurons and synapses based on memristors have been proposed to emulate neural system behavior, such as channel opening and closing driven by ionic density [

5,

6,

7,

8]. A generalization of memristors was introduced in 1976 [

9], highlighting a property in which devices can exhibit negative memristance over specific intervals of their internal variable; this phenomenon classifies the device as locally active. These locally active memristors have been utilized to model synaptic behavior [

10], capturing nonlinear responses and adaptive plasticity through their internal-state evolution. Several studies [

6,

8,

11,

12] have implemented locally active memristors with memductance described by a hyperbolic tangent function, ensuring bounded memristance characteristics. However, the exploration of fully active memristors as synaptic elements remains an open research avenue, particularly regarding their influence on the firing patterns and the synchronization properties of interconnected neural circuits.

In this contribution, we focus on a simplified memristive neural network (MNN) consisting of identical HR neurons that interact through active memristive synapses. Our model comprises two HR neurons bidirectionally coupled via locally active memristors. Although the array is small, it has physical significance since it illustrates the effects of the connection dependency on the memristor’s internal state in the emergence of coherent firing patterns in larger arrays. In this regard, previous work has investigated the emergence of identical synchronization between two neurons connected by a locally active memristor [

13]. An analytical proof of exponential synchronization in a two-neuron MNN coupled via a locally active memristor was established under suitable conditions on the memristor coupling coefficient and the initial state [

11]. Another study explored a network of three HR neurons connected by memristive synapses in a ring topology, revealing that identical synchronization occurs when the coupling strength exceeds a certain threshold [

8]. Furthermore, ref. [

12] has shown that the transition from synchronization to desynchronization depends on the MNN’s connection structure. Notably, in the exponential synchronization approach, analytical criteria provided by the Lyapunov method establish sufficient stability conditions concerning the memristor’s initial conditions and coupling strength. These criteria differ from those used in other synchronization regimes, such as generalized synchronization (GS) in mutually coupled systems, where the existence of a synchronization manifold is typically confirmed numerically, e.g., via the nearest-neighbor approach [

14].

In this work, we investigate the emergence of coherence in firing patterns of MNNs consisting of identical HR neurons, focusing on the emergence of GS and the dependence of firing patterns, such as interspike interval (ISI) and interburst interval (IBI), on the strength of the memristive connections. We propose a fully active memristive synapse with consistently negative memristance, which was bounded above and below [

6,

8,

11,

12]. Taking inspiration from previous research [

13,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], we proposed quadratic forms for the memristance function. Additionally, we demonstrate the presence of a pinched hysteresis loop (PHL) in the second and fourth quadrants, as in [

12]. That remains across various frequency values, while its lobe area decreases as frequency increases.

In the following section, we will present our MNN model of HR neurons with memristive connections and describe its synchronization challenges.

2. Preliminaries

Consider an MNN where the following equations model each node:

Here, the variable

represents voltage,

denotes recuperation, and

indicates adaptation within the neural model. This model effectively captures the dynamics of ionic currents through membrane channels, specifically potassium

and sodium

for the fast subsystem. In contrast, the ionic fluxes related to chlorine

and other leaking ions pertain to the slow variable

. The external input

facilitates inter-neuronal connections. Notably, the RH model expressed in (

1) exhibits chaotic behavior when parameters are set as

,

,

,

,

,

,

, and

[

3].

The parameter

describes the relation of fast–slow time scales in the neural model, allowing for periodic currents that trigger the

action potential displaying different patterns of bursting and spiking behavior [

3].

The interconnection between neurons is modeled as a current given by memristors of the following form:

where

is the internal state of the memristor,

is the voltage input, and

is the current output of the memristive device; with

and

representing continuous functions describing the internal dynamics and the memductive function, which is zero-at-zero and and corresponds to the derivative of the flux–charge characteristic with respect to the input variable.

We simplify the internal dynamics of the memristor:

In this simplified formulation, the vector field

lacks any leakage term, meaning that no dissipative mechanisms counterbalance the growth of

. This implies the absence of processes that would gradually diminish the internal state (memory trace). By neglecting such dissipation, we isolate the intrinsic effect of memristive coupling on neuronal excitability and synchronization.

In this contribution, we consider that all connections are modeled by memristors with the following memductance function:

where

,

, and

, with

representing the coupling strength coefficient. As such, the memductance is bounded by the following:

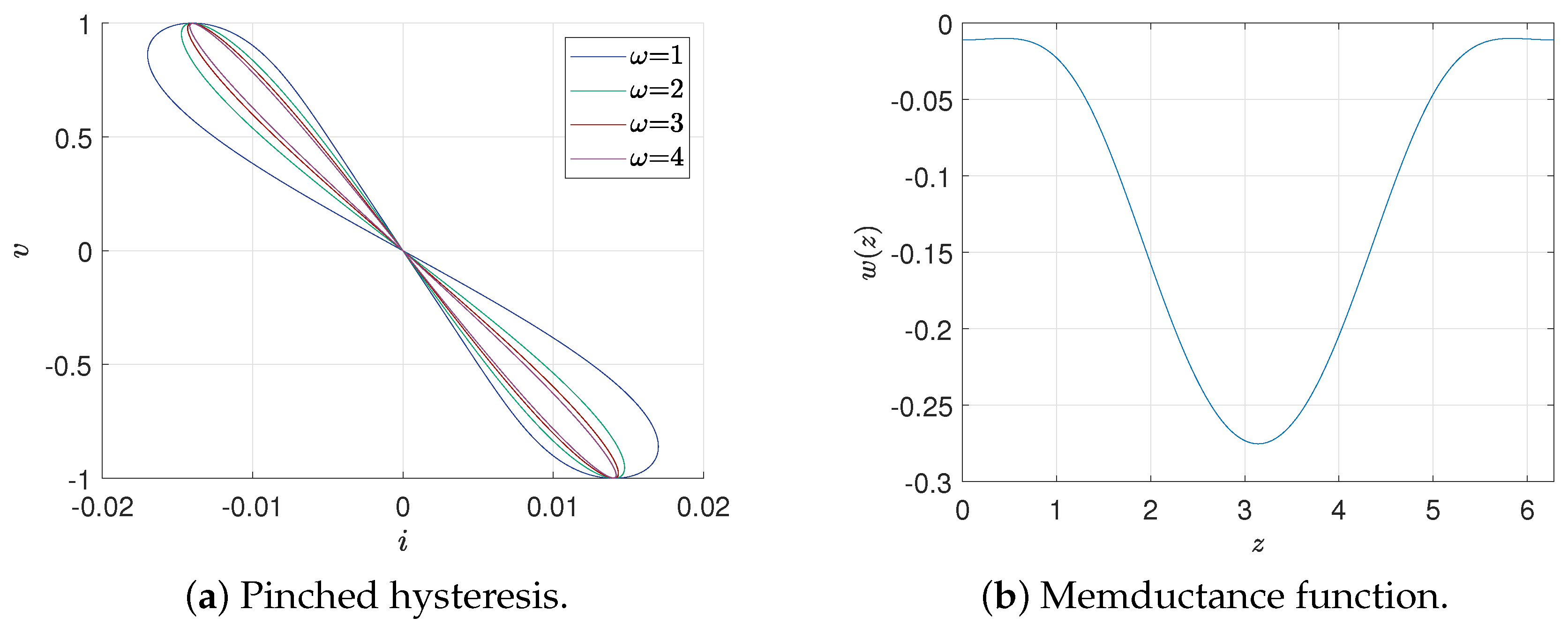

As shown in

Figure 1, under periodic input, the current–voltage diagram is a frequency-dependent pinch hysteresis. At the same time, the memductance function is quadratic and consistently negative; therefore, the model (

2)–(

4) is an active memristor [

8].

It is worth noting that ever since the mathematical generalization of the concept of a memristor in 1976 [

9], a more flexible interpretation allows us to consider memristive devices that are not strictly passive; i.e., for some intervals of the memristor’s internal variable, its memristance is negative, and it is therefore said to be locally active. This feature is directly related to ionic current channels in physiological models of neuronal membrane electrical activity. Locally active memristors have recently been proposed to model synapse behavior with different memductance functions, including the hyperbolic tangent function [

6,

8,

10,

11,

12]. The reason behind modeling memristance this way is to have a bounded memristance value. Taking inspiration from these works, a memductance function that saturates as a function of the memristor’s locally active internal variable can be proposed in the form (

4), as shown in (

5). In addition to the saturation of the memristive function, the proposed quadratic memductance function in the current–voltage variables follows the reasoning of [

13,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], which implies a cubic relation in the charge–flux interpretation of the memristor. That results in the preservation of the pinched hysteresis loop (PHL) in the second and fourth quadrants, as observed in

Figure 1.

Using the memristive synapses described above to connect two HR neurons, we have the following MNN:

where

represents the state of the

ith HR neuron;

represents the memristive synapses from neuron one to neuron two, and

refers to the connection in the opposite direction. The input to the neurons is their voltage difference

and

with

the network’s coupling strength and the memductance function (

4), which are identical for all connections.

The MNN (

6) and (

7) is said to achieve GS if after a transient time

, its states are related through a static function

that holds uniformly in time, such that

In implicit form, this can be written as

Notice that the functional relation

must be independent of time and state variables.

The main difference between generalized and identical synchronization is that in GS, the relationship between states is not the identity. That is, their temporal coordination follows a more general relation that must be static and independent of the systems’ states. As such, the stability conditions are essentially the same but in a different error dynamics: instead of the difference between states, it is the difference between the state of one system and the image of the static function that describes the relationship between the states. A simple physical interpretation is that GS appears when a system, instead of exactly copying the motion of a system, does the exact opposite. This phenomenon, sometimes called antisynchronization, is in fact one form of GS [

14].

An alternative way to describe GS is in terms of manifolds. The dynamics of (

6) and (

7) evolves in the manifold:

For MNN (

6) and (

7) to achieve GS, the manifold

must be at least locally asymptotically stable:

Notice that since the states of one system map on top of another once GS is achieved, the manifold

is effectively on the lower dimension

instead of the entire state space

. Therefore, GS is achieved if the manifold

is locally stable, that is, all transverse directions are contracting. One way to determine the local stability of the GS manifold is to characterize all its transverse directions via Lyapunov exponents (LEs). If all transverse directions have negative LEs, then the GS manifold is locally stable [

14]. The LEs can be calculated using the well-known algorithm proposed by Wolf [

20]. However, since these calculations are complex and demanding, a simplified indicator of GS is the nearest neighbor method [

21]. The nearest-neighbor method measures the distance between M points on the solution trajectories of the systems as they evolve in time; if this distance remains approximately constant, the systems are coordinated in time. A significant advantage of this method is that the number of distances to calculate scales linearly with the number of nodes in the network, unlike Lyapunov-based methods, which require evaluating variational equations and Jacobian matrices. The nearest neighbor method is computationally efficient, as it only involves storing and comparing state vectors, which are operations that are considerably faster and more amenable to parallelization. Consequently, the method is well-suited for the analysis of large and even heterogeneous networks.

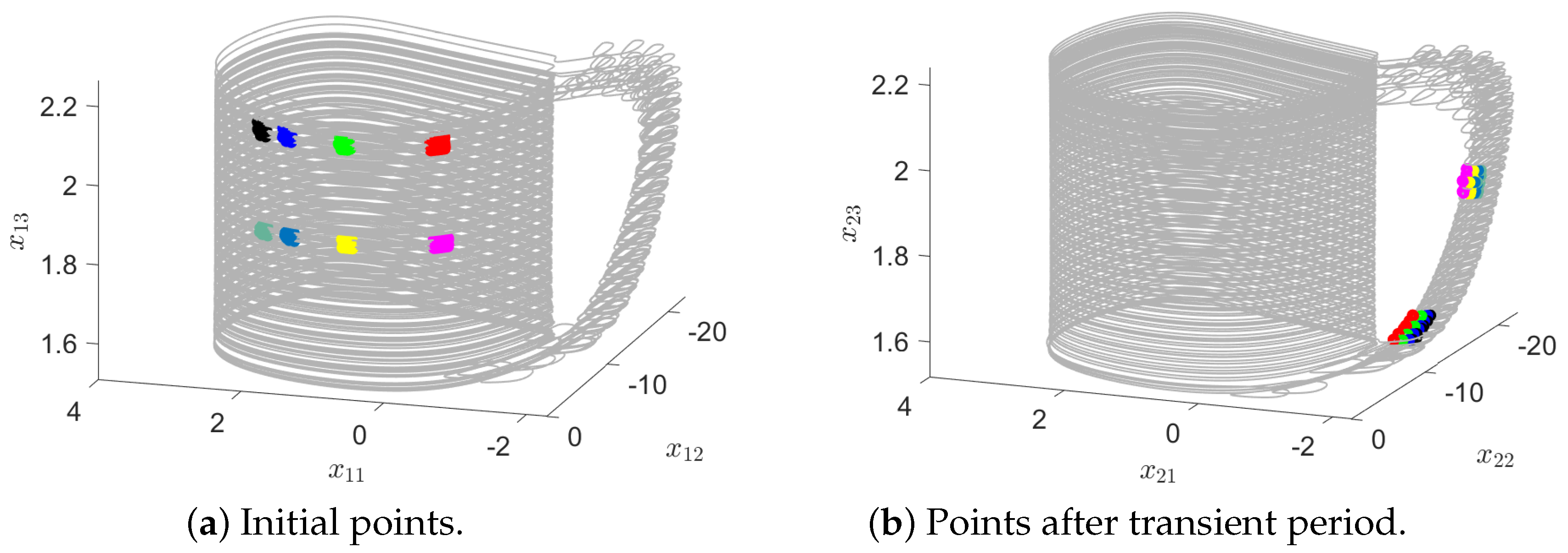

3. Numerical Results

To identify the emergence of GS in our MNN model, we apply the false neighbors approach. To illustrate its calculation, we take six points

(

) randomly chosen from the trajectory of each neuron (

Figure 2a,b). Then, after sufficient time has passed such that a full oscillation has been completed (

n iteration steps later), we identify their corresponding neighbors

(

Figure 2b). For these points, we measure their normalized average distance

d as

where

M is the number of randomly chosen points in the trajectory and

is the average distance between the chosen points and their neighbors for the first neuron, while

is the number of nearest neighbors for point

j. On average, we use

points across all experiments. Allowing

to vary has practical advantages: it provides a more reliable estimate of local distances.

As shown in

Figure 2, the trajectory moves from

to

if they are contained in a small vicinity (

). In our illustration, a region of state space is represented with the same color. Then, in the second neuron, our initial points move, after the same amount of time, to places where they are no longer neighbors. Then, there is no static functional relationship between these systems; in other words, there is no GS in our MNN model. Alternatively, in

Figure 3, where the coupling memristors have the value

, all neighbors in the second neuron are also in a small vicinity (

and

). Therefore, there is GS between these neurons.

The MNN model (

4) and (

5) with busting HR neuron parameters [

3], active memristor synapses (

) [

8] and unitary coupling strength (

) results in the trajectories shown in

Figure 4.

Notice that “burstings” appear at regular intervals but at different times for each neuron. This is more clearly shown in their third coordinate, where the anti-synchronized nature of the GS generated is easily observed. An alternative way to express this form of GS is the changes in its IBI; if it is periodic with a fixed period, then GS is achieved. In this contribution, we are particularly interested in determining the effect of memristive synapses on the emergence of GS. To this end, we evaluated the distance d to false neighbors for different values of the parameter .

Notice that for a small value, the distance is too considerable and therefore no GS is detected. For , the neighbors’ distance is nearly zero, indicating that GS is achieved.

Additionally, we consider the effects of

on the MNN’s IBI and ISI. For each value of

, we register maximum, minimum, and average values.

Figure 5 shows that as

increases, the IBI also grows. Conversely, the average ISI decreases linearly as the value of

decreases (see

Figure 6).