1. Introduction

Critical care instruction in medical schools has been the subject of research and pedagogical debate for decades [

1,

2]. Indeed, whether or not critical care management is required to be an integral part of medical school curricula at all is a subject of current discussion amongst schools. For example, a survey of Irish medical schools showed that most student exposure to critical care was five days or less, with no procedural training [

3], while Saudi schools required no critical care exposure prior to graduation [

4]. This may be due in part to the idea that critical care is tacitly instructed as a part of anesthesia, medical, and surgical rotations [

2]. However, the complexity and breadth of critical care in the setting of medical school education has been the focus of efforts to establish standardized curricula, wherein the following educational topics and skills are grouped into five broad categories [

3]: (1) neurologic, (2) respiratory, (3) cardiovascular, (4) renal and electrolyte, and (5) supplemental ICU topics, which is representative of the content in many studies as they relate to instructing students in how to treat patients in a critical care setting [

5,

6,

7].

From a teaching perspective, delivery of these concepts has been largely through a traditional curriculum, wherein students are offered instruction through a lecture-based learning system. However, attempts have been made to instruct these concepts through problem-based learning [

2] and using standardized actors [

6] to improve medical student competence and confidence in a critical care setting with improved understanding and retention of the material compared to lecture-based learning. Of all instruction methods, high-fidelity simulation is the most effective in teaching procedural concepts to students in a critical care educational setting [

8]. However, regardless of the instructional method or the curriculum developed, gaps exist in the instruction of critical care assessment, including a lack of consideration of instruction of the basic evaluation of the patient. This evaluation is not taught as a part of the standardized curricula explored above, and competency and familiarity with fundamental topics such as criticality assessments are essential to triaging and managing patient care in a critical setting.

Although students perform a criticality assessment tacitly and unconsciously, the medical student is not explicitly instructed to establish patient criticality and manage patient care accordingly as a part of performing a history and physical (H&P) [

2,

7,

8,

9]. The summation of this collected data, such as the patient’s general status combined with their initial vital readings, followed by a tailored assessment and management plan is not generally taught in a standardized algorithmic approach that reflects the knowledge level of the preclinical medical student. Indeed, instruction of this skill set seems to be limited to incidental lectures and activities for medical students [

2,

10] or else reserved for resident-level education for select specialties [

11]. Instead, classical assessment education begins under the assumption that the patient is not suffering from a serious, acute medical circumstance, with first steps in the patient encounter assuming that the patient is healthy enough to notice the setup of the encounter space, respond to a greeting appropriately, and provide a forthright history [

12]. While this patient presentation is often encountered in many specialties, formal establishment of patient stability in every encounter is required by the provider from an ethical and legal standpoint [

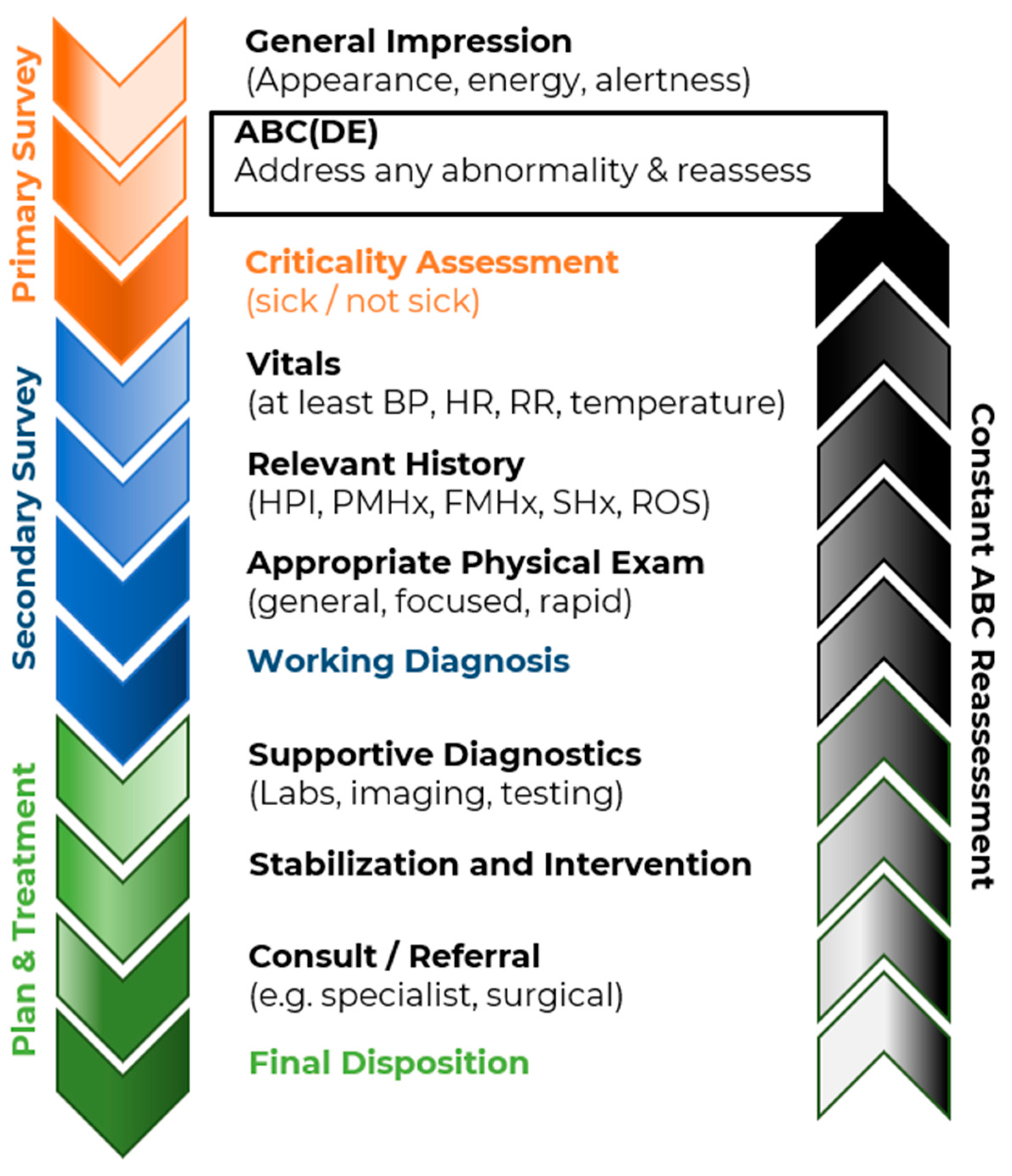

13]. The purpose of this paper is to provide a basic overview of the approach, evaluation, and initial management of a patient of undifferentiated criticality in a manner that is accessible to the medical student. The process proposed herein is an easy adjunct to the classic physical examination and history-taking methodology; indeed, the goal of this algorithmic approach is to complement and enhance the traditional evaluation methods to generate a paradigm that is easily understood and enacted by the preclinical medical student. A visual summary of this generalized algorithm is listed in

Appendix A (

Figure A1). This procedure is predicated on a simple approach to the seemingly-nebulous “sick” vs. “not sick” patient through black-and-white definitions of “critical” vs. “non-critical” patients, as defined below.

3. The Primary Survey

The “primary survey” is defined in this paper as the process by which the general medical status and associated criticality of the patient are determined [

15,

16,

17]. This assessment focuses on two metrics: the experiential gestalt experience of the provider in establishing a general impression of holistic patient status and the objective evaluation of the baseline function of individual critical systems (i.e., neurological and cardiorespiratory).

The general impression of the patient’s overall status is based on a summary of visible subjective and objective whole-patient findings. While its findings are interpreted subject to the experience of the provider [

18], the primary survey general impression assessment is important enough and simple enough that it is taught to medical personnel at nearly all scope levels [

16,

17,

19]. While at the infancy of their medical education, students may not have the clinical experience necessary to formulate comprehensive assessments and plans. However, acknowledging early on the importance for the physician’s initial assessment and general impression of a patient during every patient encounter cultivates the procedural memory and development of “clinical gestalt” required to consider its findings as experience grows.

Table 1 lists measurable qualities to be evaluated with the addition of education and experience to create this overall general impression of the patient.

A more quantitative aspect of the primary survey is the assessment of the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs), plus disability and exposure in trauma patients (ABC(DE)s). Among other reasons, each of these steps evaluates an aspect of patient condition that embodies the following qualities: (1) the aspect (ABCs and ABC(DE)s) is essential for patient vitality; (2) the aspect is easily assessed (e.g., visually or other examiner sensory cues), with the need for minimal diagnostic equipment; and (3) the aspect evaluates an organ system whose failure is potentially rapid and/or catastrophic [

13]. Qualities and metrics by which these aspects are measured are listed in

Table 1.

Ideally, both the general impression and ABC(DE) evaluations are performed in a matter of seconds by noticing patient interactions with the environment as the physician enters the room and moves to the bedside. Initial aspects of the primary survey, such as pulse and respiration rate, skin signs, and the overall appearance of the patient (e.g., disheveled, lethargic, distressed, etc.), can be established by passive visualization of the patient. Further aspects of the primary survey can be ascertained through an appropriate, lucid response to the physician–patient interaction, as described here: Doctor: “Hello, I’m Doctor ‘Name’, how are you?” Patient: “I’m not feeling well today, Doctor.” This interaction has established the following: airway and breathing are intact, as the patient spoke to the physician, and circulation is intact, as the patient is conscious and aware. Using a combination of these factors, the physician quickly assigns the patient a status of non-critical/“not-sick” (i.e., normal primary survey) as opposed to critical/“sick” (i.e., abnormal primary survey). This allows for proper triage of the patient regardless of their stated chief concern.

Although an experienced clinician can perform the actions of the primary survey nearly simultaneously, given that they typically work with a resuscitation team, the novice learner should adhere to an algorithmic approach in order to develop the clinical reasoning and eventual confidence the algorithm provides. This is for two reasons: first, this algorithmic approach, which should be used when assessing every patient regardless of stated chief concern, ensures that pathologies associated with the essential systems evaluated are not overlooked by more blatant—but lower priority—“distracting injuries”.

The second reason for which the general ABC(DE) assessment needs to be completed in order is because any abnormal finding encountered during the stages of the primary assessment must be addressed prior to moving on to the next assessment [

13]. This approach of “assess, address, reassess” is essential when performing the primary survey. That is, if the patient’s airway has collapsed, intubation is immediately indicated; the patient’s airway (A) is compromised, thereby compromising their breathing (B), which will lead to multiple organ failures. Individual interventions that address each of these unique assessments are beyond the scope of this document and should be taught separately. The order of assessment events, along with assessment targets, methods of assessment, and example critical findings, is listed in

Table 1. A visual representation is available in the primary survey flowchart listed in

Appendix A (

Figure A2). Note that qualities assessed, assessment methods, and abnormal findings are examples only and do not represent a comprehensive or exhaustive list.

5. The Secondary Survey

The purpose of the secondary survey is to delineate and streamline a general approach to patient diagnosis, from which patient management priorities can be established [

8]. Each patient type identified by the primary survey—non-critical, critical trauma, and critical medical—has a unique combination of elements that comprise the approach to gathering history, performing a physical exam, and employing diagnostic modalities towards ensuring proper patient care. Although the specifics of these elements differ between patient types, each approach is composed of the same progression of elements in a consistent arrangement to form a basic algorithm to be recognized and understood by the medical student. This algorithm is designed to emulate the Bates method taught in many programs’ equivalents to Introduction to Clinical Practice courses. In this way, the methods presented in this document build on common foundational knowledge while introducing variations to address specific patient medical concerns.

It is important for the medical student to appreciate the difference between the execution of each of these components as a part of the disparate non-critical, critical trauma, and critical medical histories. This difference is largely based on the intent of the encounter. In non-critical encounters, the intent of the encounter is likely to provide care for the patient in support of a longitudinal care relationship. In critical encounters, the plan for the encounter is to stabilize, diagnose, and treat the patient in the setting of a discreet encounter. This paradigm is used to establish the unique applications of these components, as described below.

Vital Signs—This element represents an objective measurement of physiological function that reaffirms and expands the objective findings of the primary survey [

21]. Four essential vital signs establish a comprehensive differential diagnosis for any patient chief concern and any patient status, critical or non-critical. These essential vitals are as follows: pulse rate, rhythm, and quality [

12,

21]; respiration rate rhythm and quality [

12,

21]; blood pressure [

12,

21]; and temperature [

12,

21]. Due to its indirect influence on these factors, patient pain/discomfort level—measured pseudo-quantitatively—is sometimes considered a vital sign [

12,

22,

23], but this is being abandoned as a result of the over-prescription of opioids [

24]. These vital signs can be expanded based on best practices and the initial suspicion of the patient to include pulse oximetry, bedside blood glucose-level, 3-lead electrocardiogram, and other situationally-dependent testing.

History of Present Illness (HPI)—This element is a component of the classical assessment sequence that includes establishing the pathologies that prompted the encounter [

12]. A thorough HPI is essential to establishing context for the patient’s chief concern. However, the extent to which a comprehensive generalized HPI is more appropriate than a focused or abbreviated one is largely dependent on the patient chief concern and its associated criticality [

20]. Whereas a vague, chronic complaint in a non-critical patient may require a broad approach to the HPI that gathers a wide variety of information, the HPI in a critical patient is abbreviated and associated to only signs and symptoms associated with a recent change in status and/or recent events. History-acquiring acronyms such as OPQRST/OLD-CARTS are constants in this process as information gathering tools regardless of patient chief concern and criticality [

12,

16,

17].

Past Medical History (PMHx)—This element is a component of the classical assessment sequence that provides a medical context for the patient to inform the diagnostic and treatment process [

12]. This history describes the overall previous and current health of the patient [

25]. In non-critical patients, the extent of the collection of relevant information is dependent on the purpose of the visit; acute concerns may relate the past medical history to the resolution of the concern, whereas chronic concerns and/or wellness visits may require a deep-dive into the patient’s medical past [

12]. The luxury of pursuing a detailed PMHx is not often possible with critical patients, as critical concerns are often relatable to single factors that are readily apparent in the history. For the critical trauma patient, the patient’s chronic medical conditions, medications, allergies, surgeries, and last oral intake are sufficient to render immediate aid that will likely not harm the patient [

16,

26]; in the critical medical patient, an abbreviated history limited to medical factors that might precipitate the patient’s current condition, combined with the information in the critical trauma patient history, are explored [

17,

25,

26].

Family History (FMHx)—This element is a component of the classical assessment sequence that provides insight into possible genetic etiologies that may inform the diagnostic and treatment processes [

12,

26]. This history describes the health and medical status of patient relatives—degree varies by specialty and nature of chief concern—so as to ascertain patient risk for heritable conditions [

27]. This component is largely unique to initial encounters in the non-critical setting, as this component of the patient history changes the least from encounter to encounter [

12]. FMHx may be verified during non-critical visits to inform risk assessment or changes to patient health over the course of a long-term provider–patient relationship [

26]. Thorough investigation of this component contributes minimally to critical medical patient diagnosis and management, as most patients with genetic illness contributing to acute medical emergencies are, likely along with the medical facility, aware of their diagnoses and able to communicate them directly [

27]. FMHx is largely irrelevant to the diagnosis and management of the critical trauma patient and is neither referenced nor collected as a part of that algorithm [

8].

Social History (SHx)—This element is a component of the classical assessment sequence that provides environmental context for the patient to inform the diagnostic and treatment process [

12,

26]. This history describes the patient’s lifestyle and external factors that may affect patient health. Similarly to PMHx collection, non-critical patient encounters allow for the collection of information towards a more complete picture of patient lifestyle, such as occupation, favorite interests, and exercise level [

26]. A significant investigation into these components is important for longitudinal care relationships as the risk, development, and progression of long-term conditions related to these factors may be assessed, tracked, and/or treated [

12,

28]. In the critical patient setting, individual aspects of the SHx are only relevant in the context of acute care [

15]. The use of drugs, alcohol, occupation, and high-risk lifestyle factors are collected if they are relevant to the differential diagnosis (e.g., work in an industry that provides possible exposure to a poisoning agent) or if they impact treatment options (e.g., exposure to chemicals that may interact poorly with a given intervention).

Review of Systems (ROS)—This element is a component of the classical assessment sequence that provides insight into specific aspects of the patient’s medical history that are tangentially related to the history of present illness but which are not referenced directly by the patient in their description of their present illness [

12,

29]. This history is collected system-by-system and is used to support and/or refute or make less likely diagnoses and treatments. ROS is more generalized in the non-critical patient history due to maintenance and holistic goals of such a healthcare encounter and generally encompasses more systems than those directly related to the chief concern than those collected for a critical patient encounter [

12]. Indeed, the critical medical patient ROS is limited to systems that are directly related to the chief concern and/or those that could lead to patient destabilization and decompensation, and ROS is not relevant to the diagnosis or treatment of the critical trauma patient at all [

15].

Physical Exam—This element is a component of the classical assessment sequence that provides tangible, real-time subjective and objective diagnostic information regarding the anatomy and physiology of the patient [

12]. This information in turn is used to reinforce the established patient chief concern and patient criticality assessment while also providing information regarding patient management priorities. This exam is different for each criticality of the patient established in this handout.

Non-critical patients may undergo a general exam followed by a focused physical exam commensurate with the investigation of the patient’s chief concern or, in the case of health maintenance visits, a generalized physical assessment that establishes the health and functionality of various bodily systems. These systems are selected based on a combination of provider experience and screening guidance for various risk factors based on patient demographics and history. Exposure is limited to maintain patient modesty and only expose the anatomy that is necessary for the specific exam. Abnormal findings from this exam are specific to the system being examined, are generally low-acuity, and are considered in the context of the overall current and trending patient health. This exam is performed methodically and without tremendous urgency.

Critical trauma patients are exposed entirely and undergo a complete trauma physical exam [

16,

26] wherein the provider examines and palpates the patient starting at the head and then progressing down the neck, chest, abdomen, and lower extremities. Upper extremities are examined last. The progression of this examination is consistent with its purpose, which is to establish a full picture of all patient life-threatening concerns quickly and efficiently. As such, the head-to-toe approach mirrors that of the primary survey; in both, priority systems are explored in the order of severity of failure, starting with neurological function/airway at the head and moving through breathing and circulation in the neck and chest to disability and bleeding in the extremities. As the lower extremities have larger arteries and a higher bleeding potential, these are examined before the upper extremities [

26]. Abnormal findings are universal and include the following: major bleeding; pain; deformities, contusions/crepitus, abrasions, punctures, burns, tenderness, lacerations, and swelling (DCAP-BTLS); and lack of circulation, movement, and/or sensation (CMS) in the extremities [

30]. This exam is performed meticulously, and all patient injuries are recorded [

31].

Critical medical patients undergo a rapid “checklist” general physical assessment similar to the rapid trauma assessment towards collecting diagnostic information and informing patient management [

32]. For critical medical patients without adequate history, this rapid physical may encompass nearly every body system as well as locations of insertions of interventions and specialized diagnostic equipment readouts. For critical medical patients with a known history, this exam may be abbreviated to critical systems and systems of relevance to the patient’s condition only (e.g., cardiorespiratory and neurological function augmented by investigating skin signs for Addisonian crisis). Exposure may or may not be limited based on the severity and urgency of the chief concern. Abnormal findings from this exam are specific to the systems investigated and are used in concert with one another to evaluate and treat the chief concern [

32].

Working Diagnosis—This element is a component of the classical assessment sequence that incorporates all of the information established through the primary and secondary surveys into a hypothesis regarding patient pathology [

12]. In all cases, this theory is used to direct further patient diagnostics and patient management. It is essential to establish a differential from which a most-likely working diagnosis can be winnowed, and once the main diagnosis is established, it should be checked not only against medical knowledge pertinent to the patient’s presentation but also for internal consistency relative to the findings of the primary and secondary surveys thus far.

Magnitude of the diagnosis is a good check in consistency with criticality assessment. That is, the assessed criticality of the patient should be consistent with the magnitude of the diagnosis in terms of its potential for negative effects on the patient. In non-critical patients, the working hypothesis should reflect the fact that the patient is not unstable nor in a position to rapidly decompensate, and thus the hypothesis may be of low severity. In contrast, critical trauma and critical medical patients’ status should be reflected by a high severity diagnosis. Any discrepancy between the two should lead the student to question both their initial criticality assessment and their diagnosis until the two are reconciled.

The number of diagnoses is also different based on patient criticality. While non-critical patients may have numerous sub-acute diagnoses that are considered for patient management, critical trauma and critical medical patient diagnoses should be limited to the diagnoses that represent life threats or dangers to patient stability. While the critical patient will likely have multiple concerns—multiple traumatic injuries, numerous existing diagnoses of medical problems, etc.—choosing the single greatest threat to life or stability should be the priority for the student. Otherwise, the student may become side-tracked in attempting to treat multiple distracting injuries and conditions, which may lead to a poor patient outcome [

25].

6. Plan and Treatment

After completion of the secondary survey and the establishment of the working diagnosis, a plan regarding further diagnostics and treatment must be formulated. The purpose of this plan and treatment is to affirm or refute the working diagnosis while coordinating resources and interventions to ensure a favorable patient outcome [

12]. Similarly to the secondary survey, different patient types require different elements to implement their respective plans and treatments. Unlike in the secondary survey, however, the differences in the specifics of the elements are based on patient criticality alone for plan and treatment vs. criticality and chief concern for the secondary survey [

12,

33,

34,

35]. These elements are again organized into an algorithmic pattern to be recognized and understood by the medical student. In this way, the methods presented in this document build knowledge through repetition while introducing variations to address specific patient medical concerns.

Diagnostic Modalities—This element is a component of patient management planning. The purpose of these diagnostic modalities is to differentiate, support, or refute the working diagnosis [

12]. These modalities include patient sample donations for laboratory analysis (e.g., blood, urine, swabs, etc.) as well as imaging (e.g., X-Ray, CT, MRI) and extended specialty testing (e.g., psychological assessment). The major difference between the diagnostic approaches for non-critical and critical patients is the urgency of the test results, which translates to how quickly the diagnostics are enacted and resulted. For non-critical patients, laboratory testing is collected and submitted over hours to days, and significant imaging is done on an out-patient basis. For critical patients, labs are collected and resulted in real-time, and imaging wait times are in terms of minutes and hours vs. days or weeks.

Stabilization and Intervention—This element is a component of patient treatment. The purpose of stabilizing and enacting interventions for the patient is the treatment of the patient’s chief concern. Similar to criticality, stabilization and intervention have different meanings contingent upon their respective medical contexts [

36,

37]. For the purposes of this article, “stabilization” is defined as a series of reactive measures designed to correct for deterioration of patient status, while “intervention” is defined as a procedure or medication designed to treat or correct a defined medical problem or concern. This semantic distinction is important, as it allows for the medical student’s understanding of the action in the context of the patient’s criticality; a non-critical patient should only require intervention to address the chief concern (e.g., the prescription of an antibiotic for a respiratory infection), while a critical patient may require either or both of stabilization and intervention, depending on the encounter.

Team Involvement—This element is a component of patient treatment. The purpose of involving additional team members in patient care is to ensure the involvement of individuals with specialized or unique expertise towards realization of optimal patient outcome. Again, the differences in the commission of this action based on criticality are time-based, with non-critical patients being “referred” to additional care over a period of days to weeks vs. specialists being “consulted” to critical patient care in real time. These differences tacitly acknowledge the wellness level of each class of patient through their natures, as non-critical patients are well enough to be referred away from the physician while a consult is called to the invalid critical patient.

Disposition—This element is a component of patient treatment. The purpose of dispositioning a patient is to allow the provider to formally conclude the encounter with the patient. In the non-critical setting, this disposition can include discharging the patient to the care of themself as the physician feels as though the patient is competent, informed, and well enough to no longer require direct physician supervision. While this is a possible outcome for the critical patient, it is rare; usually, the disposition of the critical patient will be to the hospital floor, to the critical care unit, to the care of a surgical team, or to a specialty hospital, whichever is indicated to provide the best care to the patient.

A summary of the secondary survey and plan and treatment section elements is listed in

Table 2 below. When combined, these elements form the non-critical patient, critical trauma patient, and critical medical patient algorithms alluded to in the sections above. A graphical representation of these respective algorithms is shown in

Appendix A (

Figure A3,

Figure A4 and

Figure A5). These flowcharts can be used by the medical student as general guidance when learning and practicing different kinds of assessments. Note that the BLS, ACLS, PALS, and ITLS algorithms are not included in this document; instead, they may be found in materials provided by their respective issuing agencies.

7. Discussion

The role of communication in criticality assessment and subsequent action—Criticality assessment has been discussed in this paper with the intent to be conducted as an individual process: that is, an assessment that is made by an individual based on that individual’s understanding of the patient’s condition in the context of the factors outlined above. Summarily, the individual then selects a course of action as specified by one of the algorithms described herein and acts accordingly. This series of events is appropriate for the new patient intake, such as a first encounter in an emergency department or when noting changes to a patient upon reassessment. However, a sizable number of encounters are likely to be hand-offs from other providers who have already performed their own assessment, and this will be communicated during handoff. Tools such as SBAR (situation, background, assessment, and recommendations) [

38] and I-PASS (illness severity, patient summary, action list, situational awareness, contingency planning, and synthesis) [

39] include components of a completed criticality assessment and suggested course of action. Additional “handoffs” may come from caregivers of the patient, such as parents or adult children, who know the patient at baseline and who may have their own opinions of whether the patient is “sick” vs. “not sick”. In all cases during receipt of this information, it is important that the recipient uses active listening skills, such as withholding judgment, asking questions, paraphrasing, and summarizing, in order to obtain a fully-formed perspective of the event. However, while it is important to acknowledge and synthesize this information, it is up to the receiving clinician or student to form their own opinion of the patient. This can be difficult if the patient is a more nuanced case, such as a patient with both a trauma and a medical complaint or a patient who otherwise does not fit into one of the three suggested categories we present in this article. These patients require the development of a clinical gestalt by the clinician or student, which will come from a combination of education and clinical experience. These cases are outside of the scope of this paper. What is attempted with this work is to lay the foundation for the development of this gestalt through the presentation of clear-cut archetypes.

Integration into medical school curricula—The approach to integrating this novel approach into medical school curricula focuses heavily on simulation as the vehicle by which to drive these concepts. Indeed, medical simulation as a field is a burgeoning set of technologies and resources that allow the learner to directly apply principles related to patient interaction and technique to their practice [

40]. These simulations can include high-fidelity equipment, standardized patients, or both, but it is imperative that the student be allowed to practice the application of the algorithms presented here in order to establish a clinical gestalt and a relative degree of comfort with discerning between “sick” and “not sick” patients. However, the basic principles of this method for teaching medical students the elements of evaluating and treating the undifferentiated patient lies in the classroom. Here, the student can assimilate the concepts established by this paper prior to applying them in simulation. There are various studies that indicate seminar-based learning [

41] and team-based learning [

42] are superior to lecture-based learning, but for the purposes of instructing the tenets of this work, we recommend using whatever format the individual medical school finds most suitable based on the structure of their respective programs. We further recommend integration into basic concepts classroom time with reinforcement through case-based learning. Once the concepts are sufficiently ingrained into the consciousness of the learner, then a simulation or series of simulations should be made available to the student during which that student may practice the algorithms that we present here. This would allow the student to understand cognitively as well as experientially the approach to the patient of undifferentiated criticality.

Future Directions—Integration of the concepts presented in this paper is largely based on their success when applied to medical student learning. Establishing this success will depend upon its qualification through research. This can either be accomplished as formal, published research as conducted at multiple institutions [

42] or as individualized feedback received by a given program [

43]. Regardless, we recommend the use of Likert scales in collecting this feedback, as these assessment tools provide a validated quantification of otherwise subjective data. These five- or seven-point scales are widespread in medical education and are used in undergraduate as well as graduate medical education to establish qualitative feedback (e.g., attitudes) from students [

44]. They would be used in this context with the goal of assessing student self-appraisal of the ability to make criticality assessments and establish “sick” vs. “not sick” patients. Additionally, including these algorithms into more quantitative assessments such as OSCEs and skills demonstrations would allow for more objective assessment of student retention of this material. However, integrating these concepts into an existing curriculum can itself present a challenge to the medical school program as well as to the learners themselves, and this problem, as well as others like it, must be considered when moving forward with integrating this work into a curriculum.

Chief among challenges facing institutions wishing to adopt this material is the fact that integrating new materials and methods of instruction can be time-consuming and difficult [

43]. This stems from the fact that instructional styles are not “one size fits all” and are unique to the institution at which they are implemented. Surmounting this challenge involves the extent to which the new material meets course goals and is applied in the context of existing methods of instruction, with the goal of student instruction at the forefront of any changes [

45]. Another challenge faced by institutions potentially wishing to incorporate this material arises from the already full course schedule taught on many campuses. Weaving additional material into an already tightly coordinated schedule can present its own unique set of troubles regarding what material to cut and what to leave in order to ensure student well-being and knowledge retention. However, as mentioned above, the methods and algorithms proposed by this work fit into existing physical diagnosis constructs (e.g., as described in Bates) [

12]. Therefore, the difficulties experienced by scheduling should be minimal, as this material represents more of a paradigm shift regarding existing course content than a novel instructional package. Finally, a third challenge in teaching this material arises from the availability of proper facilities for instruction. While many universities have developed simulation technologies for the access of the student, there are undoubtedly some institutions where the simulation capability is unsuitable for students to practice the materials and methods that we provide in this work. We therefore recommend that these algorithms be incorporated into standardized patient encounters and teaching scenarios associated with physical diagnosis, as mentioned above. In these manners, instruction of the medical student regarding “sick” vs. “not sick” and performing a proper patient assessment and treatment and disposition should be both possible and encouraged.