Trends in Medicare Utilization and Reimbursement for Traumatic Brain Injury: 2003–2021

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Trends in Procedural Volume

3.2. Trends in Reimbursement

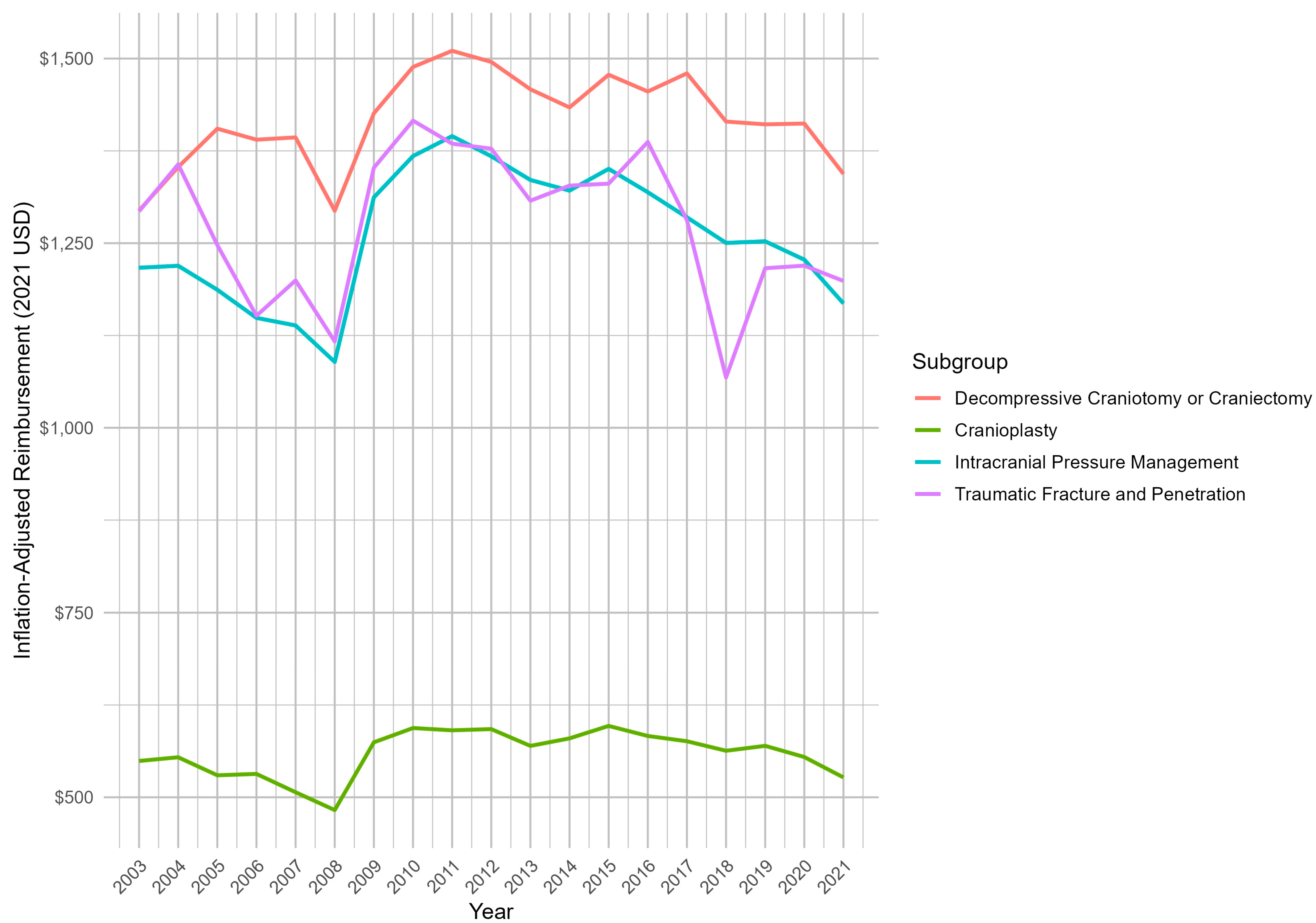

3.3. Subgroup Analysis of Reimbursement Trends

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miller, G.F.; DePadilla, L.; Xu, L. Costs of Nonfatal Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States, 2016. Med. Care 2021, 59, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haglin, J.M.; Richter, K.R.; Patel, N.P. Trends in Medicare reimbursement for neurosurgical procedures: 2000 to 2018. J. Neurosurg. 2019, 132, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornblith, E.; Diaz-Ramirez, L.G.; Yaffe, K.; Boscardin, W.J.; Gardner, R.C. Incidence of Traumatic Brain Injury in a Longitudinal Cohort of Older Adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2414223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choksi, E.J.; Mukherjee, K.; Kamal, K.M.; Yocom, S.; Salazar, R. Length of Stay, Cost, and Outcomes related to Traumatic Subdural Hematoma in inpatient setting in the United States. Brain Inj. 2022, 36, 1237–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neifert, S.N.; Chaman, E.K.; Hardigan, T.; Ladner, T.R.; Feng, R.; Caridi, J.M.; Kellner, C.P.; Oermann, E.K. Increases in Subdural Hematoma with an Aging Population—The Future of American Cerebrovascular Disease. World Neurosurg. 2020, 141, e166–e174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haglin, J.M.; Lott, A.; Kugelman, D.N.; Konda, S.R.; Egol, K.A. Declining Medicare Reimbursement in Orthopaedic Trauma Surgery: 2000–2020. J. Orthop. Trauma 2021, 35, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandi, L.A.; Jarvis, T.L.; Shrout, M.; Thornburg, D.A.; Howard, M.A.; Ellis, M.; Teven, C.M. Trends in Medicare Reimbursement for the Top 20 Surgical Procedures in Craniofacial Trauma. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2023, 34, 247–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez, J.L.; Ederaine, S.A.; Haglin, J.M.; Aragon Sierra, A.M.; Barrs, D.M.; Lott, D.G. Medicare Reimbursement Trends for Facility Performed Otolaryngology Procedures: 2000–2019. Laryngoscope 2021, 131, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hersh, A.M.; Dedrickson, T.; Gong, J.H.; Jimenez, A.E.; Materi, J.; Veeravagu, A.; Ratliff, J.K.; Azad, T.D. Neurosurgical Utilization, Charges, and Reimbursement After the Affordable Care Act: Trends From 2011 to 2019. Neurosurgery 2023, 92, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romaniuk, M.; Mahdi, G.; Singh, R.; Haglin, J.; Brown, N.J.; Gottfried, O. Recent Trends in Medicare Utilization and Reimbursement for Spinal Cord Stimulators: 2000–2019. World Neurosurg. 2022, 166, e664–e671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dijck, J.T.J.M.; Dijkman, M.D.; Ophuis, R.H.; de Ruiter, G.C.W.; Peul, W.C.; Polinder, S. In-hospital costs after severe traumatic brain injury: A systematic review and quality assessment. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, R. Traumatic Brain Injury Hospital Stays Are Longer, More Costly. JAMA 2020, 323, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Part B National Summary Data File (Previously Known as BESS)|CMS. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/part-b-national-summary-data-file (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Inpatient Hospital Care Coverage. Available online: https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/inpatient-hospital-care (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- Inflation Calculator|Find US Dollar’s Value from 1913–2024. Available online: https://www.usinflationcalculator.com/ (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) Formula and Calculation. Investopedia. Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/cagr.asp (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Dicpinigaitis, A.J.; Al-Mufti, F.; Cooper, J.B.; Kazim, S.F.; Couldwell, W.T.; Schmidt, M.H.; Gandhi, C.D.; Cole, C.D.; Bowers, C.A. Nationwide trends in middle meningeal artery embolization for treatment of chronic subdural hematoma: A population-based analysis of utilization and short-term outcomes. J. Clin. Neurosci. Off. J. Neurosurg. Soc. Australas 2021, 94, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weeks, W.B.; Cao, S.Y.; Smith, J.; Wang, H.; Weinstein, J.N. Trends in Characteristics of Adults Enrolled in Traditional Fee-for-Service Medicare and Medicare Advantage, 2011–2019. Med. Care 2022, 60, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemens, J.; Gottlieb, J.D.; Molnár, T.L. The Anatomy of Physician Payments: Contracting Subject to Complexity. NBER Work Pap. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org//p/nbr/nberwo/21642.html (accessed on 6 August 2024).

- Quereshy, H.A.; Quinton, B.A.; Cabrera, C.I.; Li, S.; Tamaki, A.; Fowler, N. Medicare reimbursement trends from 2000 to 2020 in head and neck surgical oncology. Head Neck 2022, 44, 1616–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haglin, J.M.; Zabat, M.A.; Richter, K.R.; McQuivey, K.S.; Godzik, J.; Patel, N.P.; Eltorai, A.E.M.; Daniels, A.H. Over 20 years of declining Medicare reimbursement for spine surgeons: A temporal and geographic analysis from 2000 to 2021. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2022, 37, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatuki, T.A.; Zvonarev, V.; Rodas, A.W. Prevention of Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Significance, New Findings, and Practical Applications. Cureus 2020, 12, e11225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, L.; Fingar, K. Inpatient Stays and Emergency Department Visits Involving Traumatic Brain Injury, 2017 #255. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Available online: https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb255-Traumatic-Brain-Injury-Hospitalizations-ED-Visits-2017.jsp (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Glass, K.P.; Anderson, J.R. Relative value units: From A to Z (Part I of IV). J. Med. Pract. Manag. MPM 2002, 17, 225–228. [Google Scholar]

- Wilensky, G.R. Will MACRA Improve Physician Reimbursement? N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1269–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangji, N.F. Repeal of the Sustainable Growth Rate: An overview for surgeons. Am. J. Surg. 2014, 208, 597–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| CPT Code | Procedure |

|---|---|

| 61154 | Twist drill, burr hole(s), or trephine procedures on the skull, meninges, and brain |

| 61312 | Evacuation of hematoma, supratentorial, extradural, or subdural |

| 61316 | Incision and placement of a cranial bone graft under the skin; used as an add-on with a craniectomy code |

| 61322 | Craniectomy or craniotomy, decompressive, with or without duraplasty for treatment of intracranial hypertension without evacuation of associated intraparenchymal hematoma; without lobectomy |

| 61323 | Craniectomy or craniotomy, decompressive, with or without duraplasty for treatment of intracranial hypertension without evacuation of associated intraparenchymal hematoma; with lobectomy |

| 61570 | Excision of foreign body from the brain |

| 61571 | Treatment of penetrating wound of the brain |

| 62005 | Elevation of a compound or comminuted extradural depressed skull fracture |

| 62010 | Elevation of a depressed skull fracture |

| 62140 | Cranioplasty: large (>5 cm) complex or multiple |

| 62141 | Cranioplasty: small (<5 cm) or simple |

| 62143 | Replacement of a skull bone flap or prosthetic plate |

| 62148 | Incision and retrieving a cranial bone graft that has been stored in the abdomen or in the inner lining; add-on with a cranioplasty code |

| 62223 | Creation of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt |

| CPT Code | Procedural Volume—Year 2003 | Procedural Volume—Year 2021 | % Change Procedural Volume (2003–2021) (%) | Linear Regression p-Value (2003–2021) | Linear Regression R2-Value (2003–2021) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 61154 | 8056 | 4123 | −48.82 | <0.001 | 0.950 |

| 61312 | 9768 | 8443 | −13.56 | <0.001 | 0.552 |

| 61316 | 31 | 85 | +174.19 | 0.295 | 0.009 |

| 61322 | 77 | 769 | +898.70 | <0.001 | 0.947 |

| 61323 | 84 | 118 | +40.48 | 0.031 | 0.201 |

| 61570 | 25 | 19 | −24.00 | 0.001 | 0.426 |

| 61571 | 35 | 11 | −68.57 | <0.001 | 0.590 |

| 62005 | 32 | 30 | −6.25 | 0.025 | 0.218 |

| 62010 | 106 | 49 | −53.77 | <0.001 | 0.680 |

| 62140 | 1347 | 690 | −48.78 | <0.001 | 0.718 |

| 62141 | 755 | 673 | −10.86 | 0.492 | −0.029 |

| 62143 | 318 | 690 | +116.98 | <0.001 | 0.642 |

| 62148 | 24 | 29 | 20.83 | 0.557 | −0.037 |

| 62223 | 6493 | 7244 | +11.57 | 0.258 | 0.020 |

| Total | 27,151 | 22,973 | −15.39 | <0.001 | 0.594 |

| CPT Code | Mean Reimbursement per Procedure— Year 2003 (2003 USD) | Mean Reimbursement per Procedure— Year 2021 (2021 USD) | Unadjusted Total % Change in Reimbursement per Procedure (2003–2021) (%) | % Change in CPI (2003–2021) (%) | t-Test Between Reimbursement per Procedure % Change and CPI p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 61154 | 720.09 | 1149.54 | +59.64 | ||

| 61312 | 1045.02 | 1689.9 | +61.71 | ||

| 61316 | 70.03 | 72.41 | +3.40 | ||

| 61322 | 1290.72 | 1977.05 | +53.17 | ||

| 61323 | 1275.54 | 1981.94 | +55.38 | ||

| 61570 | 786.12 | 1317.54 | +67.60 | ||

| 61571 | 1200.18 | 1667.65 | +38.95 | ||

| 62005 | 545.27 | 836.75 | +53.46 | ||

| 62010 | 717.42 | 973.31 | +35.67 | ||

| 62140 | 336.29 | 530.64 | +57.79 | ||

| 62141 | 449.49 | 731.09 | +62.65 | ||

| 62143 | 423.99 | 742.90 | +75.22 | ||

| 62148 | 97.18 | 103.02 | +6.01 | ||

| 62223 | 536.04 | 665.80 | +24.21 | ||

| Total | 678.10 | 1031.40 | +46.78 | +47.28 | 0.214 |

| CPT Code | Mean Reimbursement per Procedure—Year 2003 (2021 USD) | Mean Reimbursement per Procedure—Year 2021 (2021 USD) | Adjusted Total % Change in Reimbursement per Procedure (2003–2021) (%) | Adjusted CAGR (%) | Linear Regression p-Value (2003–2021) | Linear Regression R2-Value (2003–2021) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 61154 | 1106.04 | 1149.54 | +3.93 | +0.20 | 0.010 | 0.289 |

| 61312 | 1661.12 | 1689.90 | +1.73 | +0.09 | 0.058 | 0.148 |

| 61316 | 103.14 | 72.41 | −29.79 | −1.84 | <0.001 | 0.742 |

| 61322 | 1901.01 | 1977.05 | +4.00 | +0.21 | 0.047 | 0.166 |

| 61323 | 1878.65 | 1981.94 | +5.50 | +0.28 | 0.513 | −0.032 |

| 61570 | 1344.25 | 1317.54 | −1.99 | −0.11 | 0.835 | −0.056 |

| 61571 | 1809.74 | 1667.65 | −7.85 | −0.43 | 0.255 | 0.021 |

| 62005 | 852.37 | 836.75 | −1.83 | −0.10 | 0.426 | −0.019 |

| 62010 | 1166.27 | 973.31 | −16.54 | −0.95 | 0.054 | 0.163 |

| 62140 | 564.72 | 530.64 | −6.03 | −0.33 | 0.256 | 0.021 |

| 62141 | 756.91 | 731.09 | −3.41 | −0.18 | 0.068 | 0.134 |

| 62143 | 730.80 | 742.90 | +1.65 | +0.09 | 0.076 | 0.125 |

| 62148 | 144.35 | 103.02 | −28.63 | −1.76 | <0.001 | 0.780 |

| 62223 | 882.97 | 665.80 | −24.60 | −1.47 | 0.008 | 0.308 |

| Total | 1064.45 | 1031.39 | −3.11 | −0.45 | 0.585 | −0.040 |

| Subgroup | CPT Code | Mean Reimbursement per Procedure—Year 2003 (2021 USD) | Mean Reimbursement per Procedure—Year 2021 (2021 USD) | Adjusted Total % Change in Reimbursement per Procedure (2003–2021) (%) | Linear Regression p-Value (2003–2021) | Linear Regression R2-Value (2003–2021) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decompressive Craniotomy/ Craniectomy | 61316 | 1294.26 | 1343.80 | +3.83 | 0.155 | 0.063 |

| 61322 | ||||||

| 61323 | ||||||

| Cranioplasty | 62140 | 549.19 | 526.91 | −4.10 | 0.176 | 0.052 |

| 62141 | ||||||

| 62143 | ||||||

| 62148 | ||||||

| Intracranial Pressure Management | 61154 | 1216.71 | 1168.41 | −4.00 | 0.285 | 0.012 |

| 61312 | ||||||

| 62223 | ||||||

| Traumatic Fracture and Penetration | 61570 | 1293.16 | 1198.81 | −7.30 | 0.542 | −0.035 |

| 61571 | ||||||

| 62005 | ||||||

| 62010 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Inzerillo, S.; Jones, S. Trends in Medicare Utilization and Reimbursement for Traumatic Brain Injury: 2003–2021. Trauma Care 2024, 4, 282-293. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare4040024

Inzerillo S, Jones S. Trends in Medicare Utilization and Reimbursement for Traumatic Brain Injury: 2003–2021. Trauma Care. 2024; 4(4):282-293. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare4040024

Chicago/Turabian StyleInzerillo, Sean, and Salazar Jones. 2024. "Trends in Medicare Utilization and Reimbursement for Traumatic Brain Injury: 2003–2021" Trauma Care 4, no. 4: 282-293. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare4040024

APA StyleInzerillo, S., & Jones, S. (2024). Trends in Medicare Utilization and Reimbursement for Traumatic Brain Injury: 2003–2021. Trauma Care, 4(4), 282-293. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare4040024