1. Introduction

Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody targeting CD20, commonly used to treat autoimmune diseases such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) and rheumatoid arthritis [

1]. While generally well-tolerated, serious adverse events such as infusion reactions and infections are well-documented [

2]. However, rituximab-induced myocardial infarction (MI) is exceedingly rare and not fully understood. Reports of acute coronary syndromes following rituximab infusions have suggested mechanisms such as vasospasm, immune-mediated endothelial damage, and hypersensitivity reactions [

3,

4,

5]. However, the few documented case reports of MI following rituximab infusion are those with older patients, risk factors such as coronary artery disease, male age, or smokers used for the treatment of lymphoma, myasthenia gravis, rheumatoid arthritis, and thrombocytopenia purpura [

6,

7].

We describe a unique clinical presentation involving a woman in her mid-20s with no traditional cardiovascular risk factors who developed an acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) within minutes of receiving her first rituximab infusion, followed by a recurrence upon re-exposure during a second admission. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of suspected rituximab-induced STEMI in a patient with GPA, and at an unusually young age. The report underscores the importance of recognizing the potential cardiotoxic effects of rituximab, particularly in patients with autoimmune diseases and underlying hypercoagulability [

8].

2. Patient Information

A 26-year-old previously healthy woman developed acute chest tightness toward the end of a 4 h rituximab (Rituxan) infusion at an outside hospital. This progressed to crushing, left-sided chest pain shortly after the infusion was completed.

She had been undergoing outpatient evaluation by internal medicine and rheumatology teams for the preceding 3–4 weeks due to a constellation of concerning symptoms, including:

Fatigue

Ankle purpura

Left-sided Bell’s palsy

Bilateral hearing loss

Hemoptysis

Episcleritis

As her condition worsened during the ongoing diagnostic work-up, the decision was made to initiate treatment with 1 g rituximab while continuing further evaluation. This was her first therapeutic intervention.

Her outside initial lab evaluation revealed the following:

Creatinine: 3.6 mg/dL (baseline 0.6 mg/dL)

c-ANCA: Positive (1:160)

Anti-PR3 antibody: Positive

ANA, RNP antibody, RF: Positive

Cryoglobulins: Trace

- ○

Negative IgM, IgG, and IgA cryoprecipitate

- ○

No immunoglobulin detected by immunofixation electrophoresis

ESR: 106 mm/hr, CRP: 194 mg/L

Hemoglobin: 8.1 g/dL

Platelets: 246,000/mm3

Urinalysis: +3 blood, +2 protein, RBC casts

JAK2 mutation: Negative

Anti-cardiolipin antibody: Negative

Anti-lupus antibody: Negative

Renal biopsy: crescentic and necrotizing glomerulonephritis, pauci-immune type (resulted during her first hospitalization at our hospital, not known at the time of admission)

The patient’s lab findings were suggestive of GPA, given the positive c-ANCA and anti-PR3 antibodies, acute kidney injury with RBC casts, and systemic inflammation (elevated ESR/CRP). Urinalysis findings and elevated creatinine levels support the diagnosis of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis, a common renal manifestation of GPA.

She had no prior cardiac history, no family history of early coronary artery disease, did not smoke, and had no other cardiovascular risk factors. The patient did not use tobacco, alcohol, or recreational drugs.

3. Clinical Findings

General: Acute distress during the chest pain episode

CV Exam: Tachycardia, no murmurs/rubs/gallops

Skin: Ankle purpura

Neuro: Left-sided Bell’s palsy

ENT: Bilateral hearing deficit

Eye: Episcleritis

Lungs: Bibasilar crackles

4. Initial Diagnostic Assessment

Cardiac catheterization confirmed a 100% left circumflex artery occlusion, and a stent was placed to restore perfusion (

Figure 1). For anticoagulation, she was started on a continuous heparin infusion and aspirin 81 mg following stent placement, then transitioned to apixaban 5 mg twice daily and continued on aspirin at discharge. In-patient, she was given IV methylprednisolone 125 mg daily for 6 days.

The initial presentation of STEMI was concerning for a reaction to rituximab, especially given the temporal proximity of the infusion to symptom onset. Other diagnoses, such as atherosclerotic plaque rupture, were considered, but they were less likely due to the patient’s young age and no risk factors.

Laboratory testing and imaging during the first cardiac event:

Elevated troponin to 72,000 ng/L

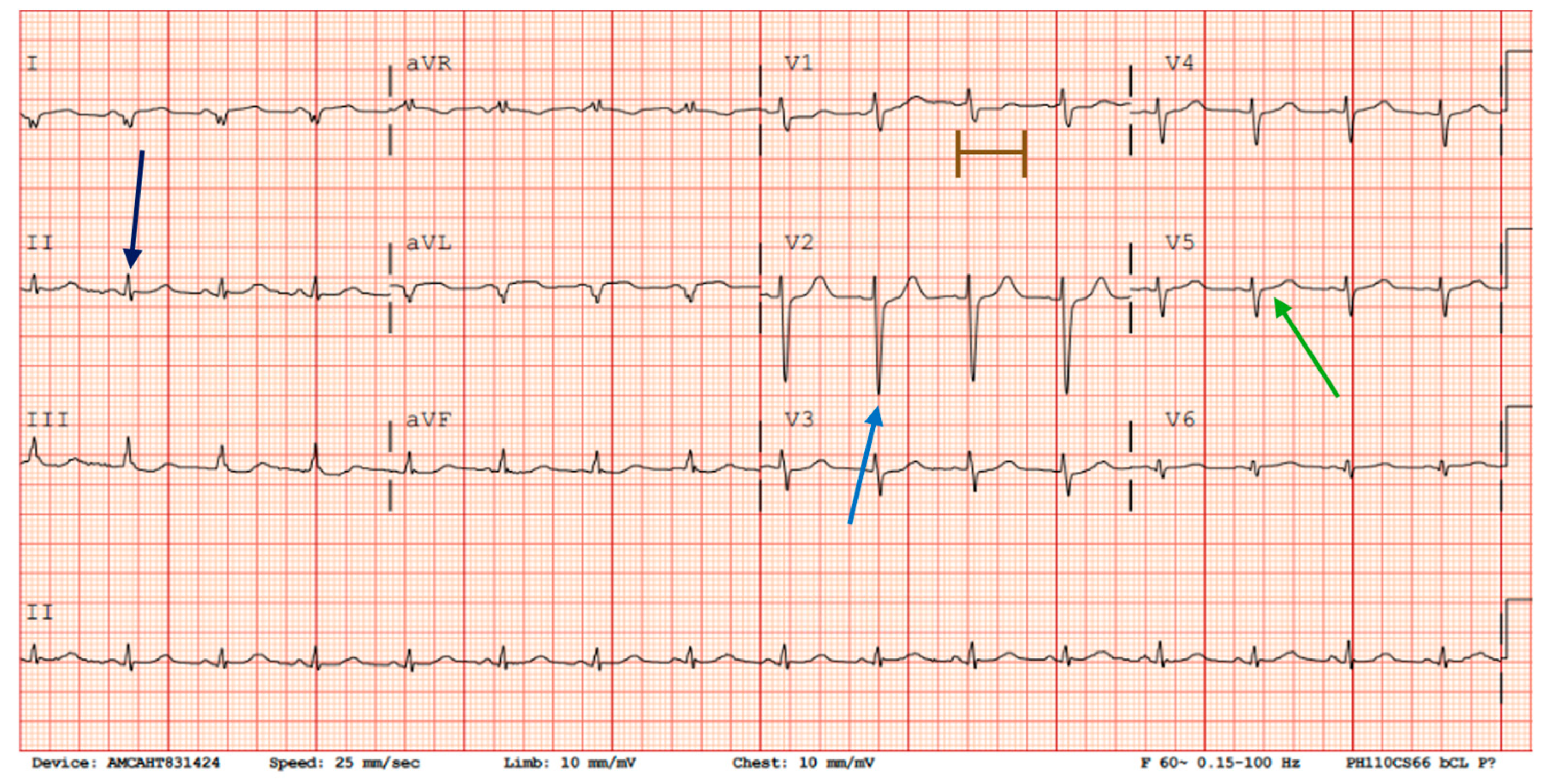

Initial echocardiogram (ECG): low voltage in extremity leads, probably right ventricular hypertrophy, borderline lateral ST elevation, borderline prolonged QT interval. (

Figure 2).

Cardiac catheterization confirmed a 100% left circumflex artery occlusion (

Figure 1).

Cardiac MRI: Hypokinesis, LV thrombus

TEE: No PFO or endocarditis

Echocardiogram: Small echo density on the posterior mitral valve; moderately reduced LV function.

The initial STEMI was attributed to autoimmune-mediated vasculitis and hypercoagulability rather than rituximab infusion. A decision was made to delay further immunosuppressive therapy for one month to reduce thrombotic risk.

5. Second Admission

Two weeks after discharge, the patient was readmitted for worsening renal function related to her GPA, with a creatinine level of 4.5 mg/dL noted at an outpatient follow-up. Given fertility concerns with cyclophosphamide, we agreed to proceed with a second dose of rituximab (Rituxan) as a rechallenge, despite concerns about thrombotic risk.

She was premedicated with diphenhydramine 50 mg PO and acetaminophen 650 mg, and the infusion of 250 mg was run at 50 mL/hour for 37 min. During the second infusion, chest tightness recurred within 30 min after starting. An ECG showed right axis deviation, abnormal T waves in the lateral leads, and a decrease in overall voltage compared to the ECG 5 days prior. Troponin levels rose to 164 ng/L before trending down to 146 ng/L 4 h later (

Figure 3). No repeat echocardiogram or catheterization was performed, as her symptoms resolved following discontinuation of the infusion. The recurrence of symptoms and biomarker elevation strongly implicated rituximab as the trigger for both the initial and subsequent cardiac events.

The infusion was stopped, and immunosuppressive management was revised to balance disease control and thrombotic risk. Her treatment plan was to proceed with cyclophosphamide 500 mg infusions every 2 weeks for 6 doses, prednisone taper starting at 60 mg, leuprolide 3.5 mg injections every 28 days for fertility preservation while performing cyclophosphamide infusions, and atorvastatin 40 mg/day.

Balancing immunosuppressive therapy and thrombotic risk in this patient was further complicated by her desire to preserve fertility, precluding cyclophosphamide as an initial treatment option. The decision to proceed with rituximab again, despite its risks, underscores the importance of individualized care in complex cases.

6. Therapeutic Intervention

Following the initial diagnosis of STEMI, the patient was managed with urgent cardiac catheterization and placement of a drug-eluting stent in the occluded left circumflex artery. She started dual antiplatelet therapy, systemic anticoagulation for the left ventricular thrombus visualized on cardiac MRI, and high-dose corticosteroids for presumed systemic vasculitis. Given the suspected role of rituximab in triggering the myocardial infarction, further biologic therapy was initially deferred.

After confirming a diagnosis of granulomatosis with polyangiitis on renal biopsy, treatment planning was complicated by the patient’s desire to preserve fertility. Cyclophosphamide, a common first-line agent in severe vasculitis, was initially avoided due to its gonadotoxicity. A shared decision was made to cautiously reintroduce rituximab with premedication (acetaminophen 650 mg and diphenhydramine 50 mg orally), and a reduced dose of 250 mg was administered at 50 mL/hour. However, chest pain recurred within 30 min of initiating the infusion, prompting immediate discontinuation. ECG changes and troponin elevation confirmed a second episode of myocardial injury, likely due to rituximab rechallenge.

Given the reproducibility of the adverse event, rituximab was permanently discontinued. The patient’s immunosuppressive regimen was adjusted to include high-dose corticosteroids, intravenous cyclophosphamide, and leuprolide acetate for ovarian suppression and fertility preservation. She tolerated this regimen well without recurrence of cardiac symptoms.

7. Follow-Up and Outcomes

Following the second event, the patient tolerated cyclophosphamide and corticosteroids without further cardiac complications. She continued on a GPA treatment plan and demonstrated good adherence to it. Follow-up echocardiography showed mild improvement in LV function and resolution of LV thrombus. Creatinine trended downward. No further chest pain was reported.

8. Timeline

Day 0 (First Rituximab Infusion):

At the end of a 4 h 1 g rituximab infusion, the patient developed sudden, severe substernal chest pain. Vitals were stable, but the ECG showed new ST elevations. Troponin was significantly elevated, peaking at 72,000 ng/L. Emergent cardiac catheterization revealed 100% occlusion of the left circumflex artery; a drug-eluting stent was placed (

Figure 1). No evidence of underlying atherosclerosis was noted.

Days 1–5:

Cardiac MRI revealed hypokinesis of the lateral wall and a left ventricular thrombus. The TEE showed no intracardiac shunt or valvular vegetations. An echocardiogram noted a moderately reduced ejection fraction with a mobile echo density on the posterior mitral valve leaflet. Troponins trended down. Given the temporal association and clean coronary anatomy, rituximab was held. The patient was managed with anticoagulation and PEXIVAS steroid taper. Given her biopsy findings, results with pauci-immune glomerulonephritis, she was diagnosed with GPA.

Day 14:

The patient was readmitted for worsening renal function (Cr peaked at 4.5 mg/dL) and rising inflammatory markers.

Day 16:

After a multidisciplinary discussion, rituximab was restarted at a reduced dose (250 mg IV) with pre-treatment (diphenhydramine 50 mg PO, acetaminophen 650 mg PO).

During the Second Infusion:

At a 50 mL/hr rate, the patient again developed chest pain, this time within the first 30 min of infusion. ECG now showed new T-wave inversions in lead V5 and lowered QRS voltage in limb leads. Troponin increased to 164 ng/L, then trended down to 146 ng/L within 4 h, consistent with reinfarction or myocardial injury. No hemodynamic instability was noted.

After the Second Event:

Rituximab was permanently discontinued. The patient was transitioned to cyclophosphamide, continued on high-dose corticosteroids, and given leuprolide for ovarian suppression and fertility preservation.

9. Discussion

The evidence for rituximab-induced myocardial injury includes:

Temporal association between infusion and STEMI onset during the first event.

Recurrence of chest pain, ECG changes, and troponin elevation during rituximab rechallenge.

Absence of alternative explanations such as structural heart defects or coronary artery disease.

Rituximab-associated myocardial injury is rare but potentially life-threatening. Previous reports suggest mechanisms may include hypersensitivity reactions, cytokine release, vasospasm, or direct endothelial injury [

9,

10]. In this case, the reproducible myocardial injury, including ECG changes and marked troponin elevation, following two separate rituximab exposures in a young patient with no cardiovascular risk factors strongly implicates rituximab as the causative agent.

Importantly, the initial event occurred in the absence of other medications or hemodynamic instability. The patient’s underlying autoimmune vasculitis likely predisposed her to vascular injury or thrombosis, but the timing and recurrence after rituximab exposure are particularly compelling. The absence of coronary artery disease on angiography and other structural defects on echocardiography supports a non-atherosclerotic mechanism.

This case also highlights the complexities of treatment decisions in young women with autoimmune diseases. Fertility preservation is a key consideration in selecting immunosuppressive therapy. Ultimately, individualized care plans involving rheumatology, cardiology, and reproductive endocrinology were necessary.

Key learning point: Even in the absence of traditional risk factors, clinicians should remain vigilant for cardiac events during rituximab infusions, especially in patients with inflammatory or vasculitis disease states.