Geochemical Modeling from the Asteroid Belt to the Kuiper Belt: Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Solar System and Astronomical Objects Beyond Mars

2.2. Geochemical Modeling and Celestial Objects

2.3. Bibliographic Screening and Analysis

3. Literature Review of Geochemical Modeling Studies

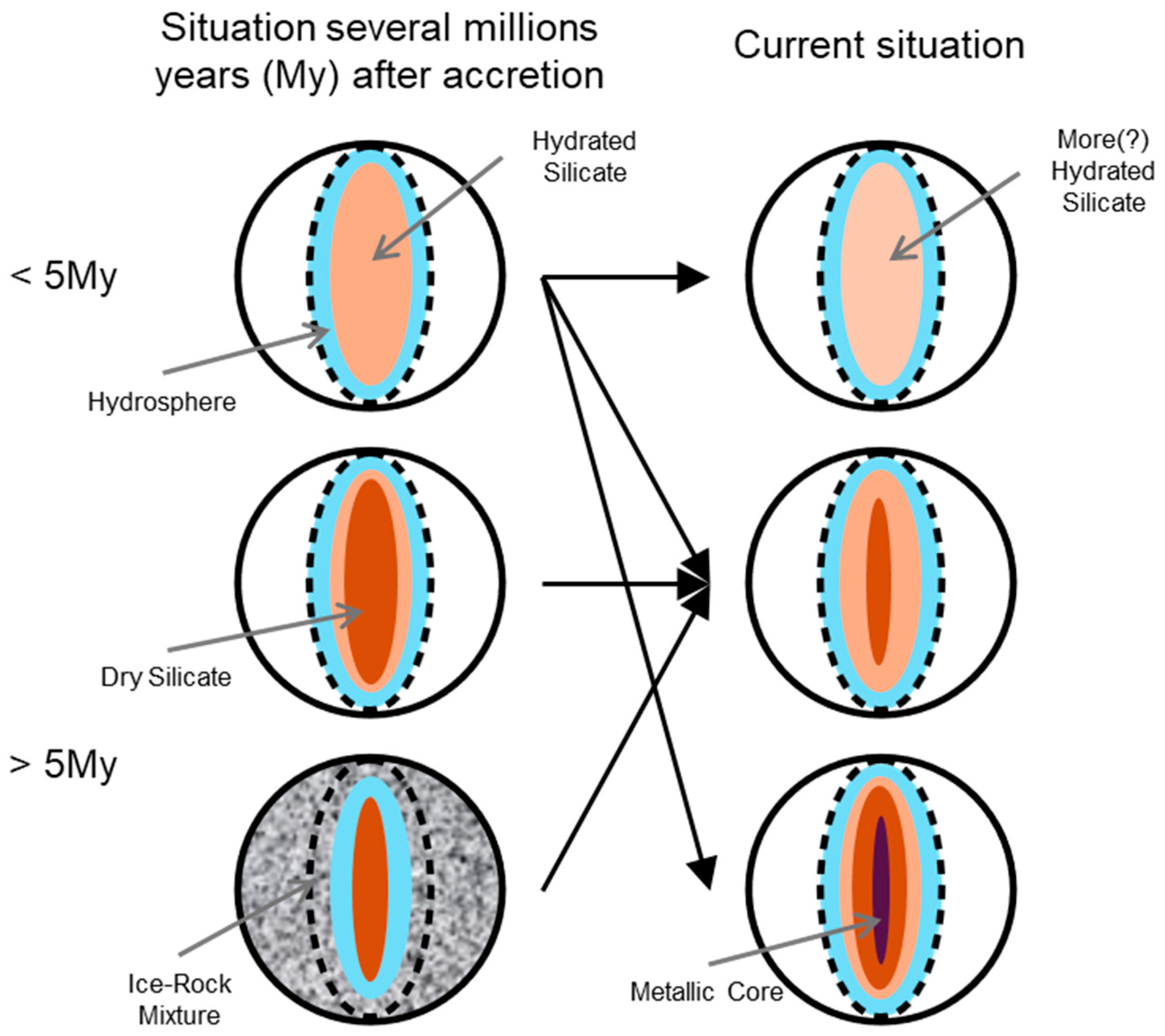

3.1. Ceres

3.2. Jupiter

3.3. Saturn

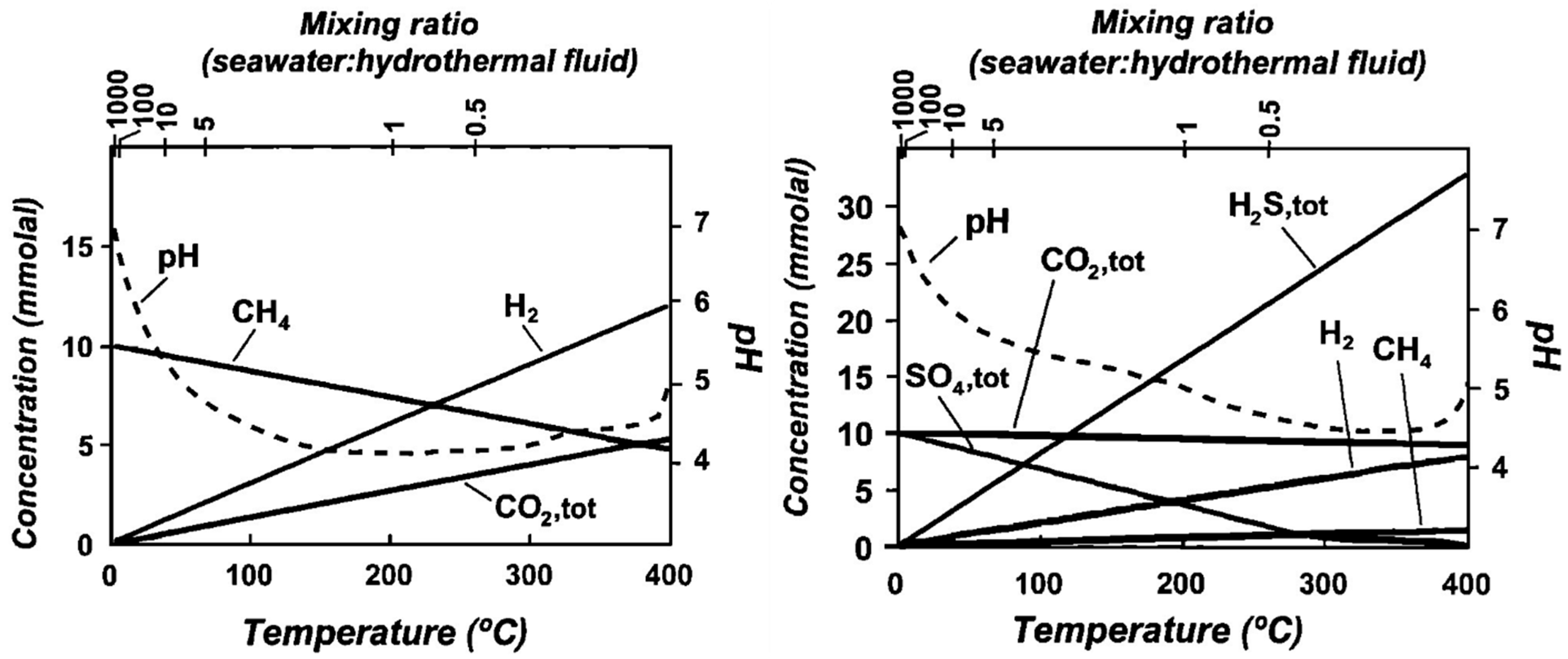

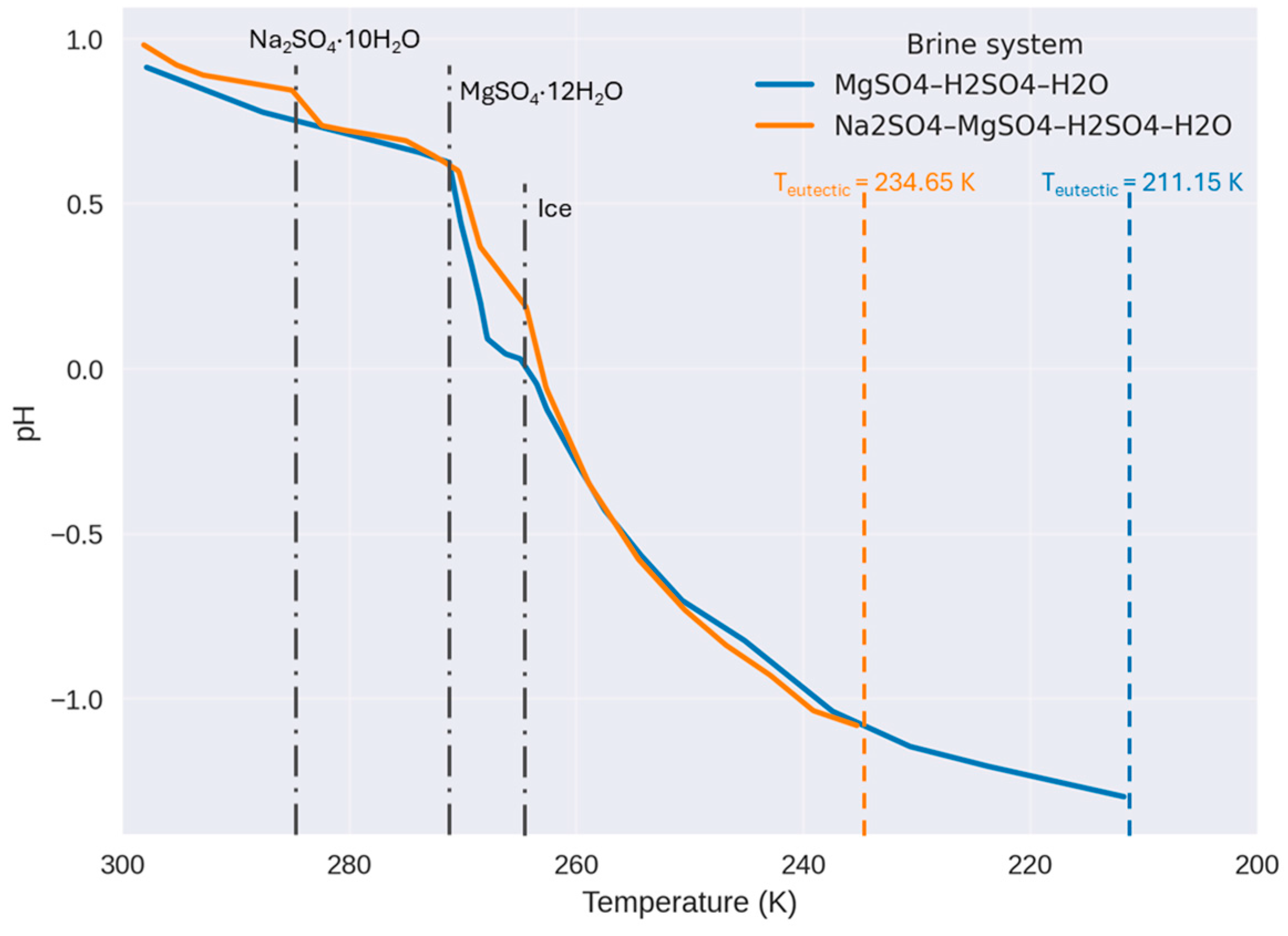

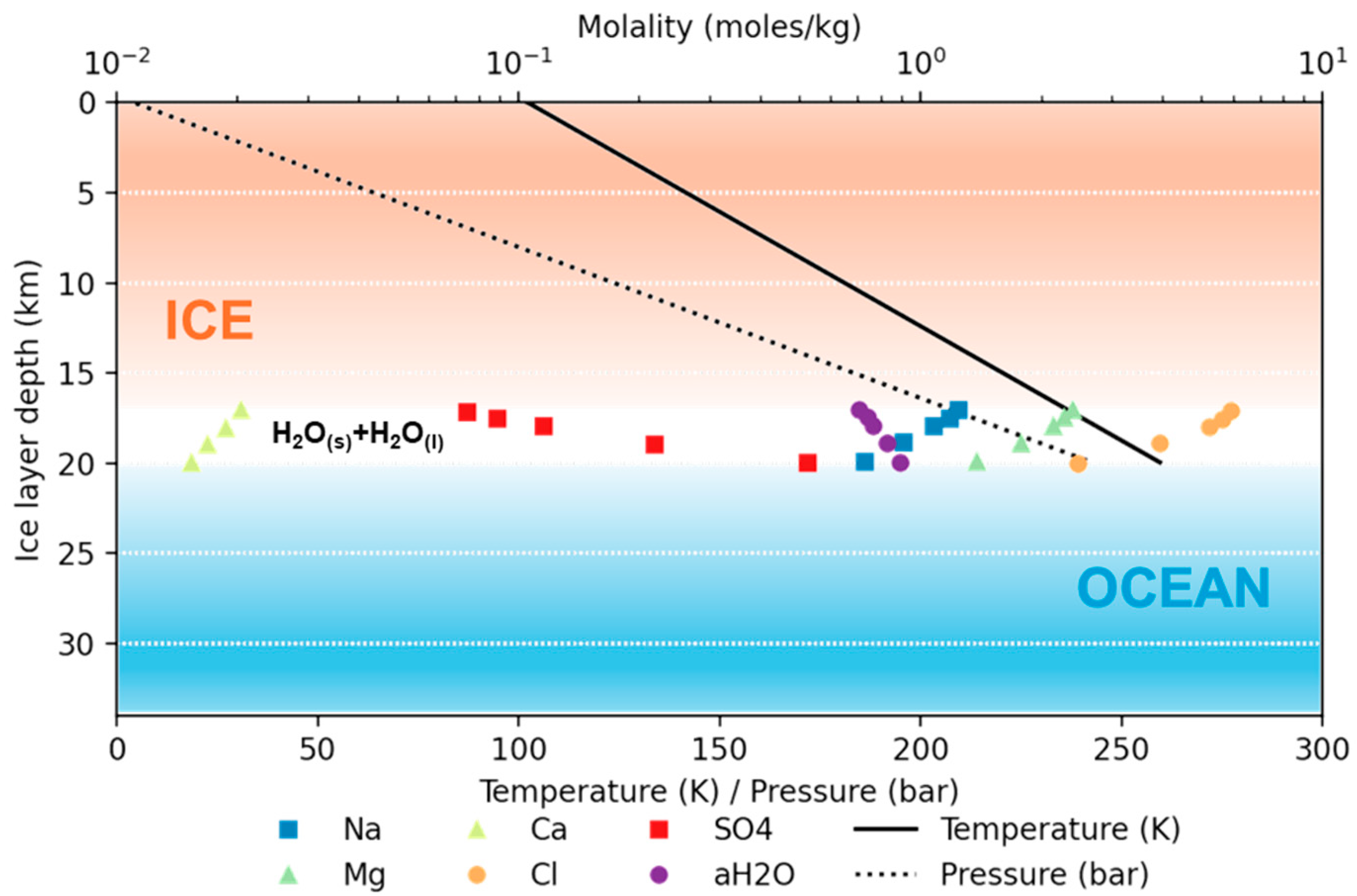

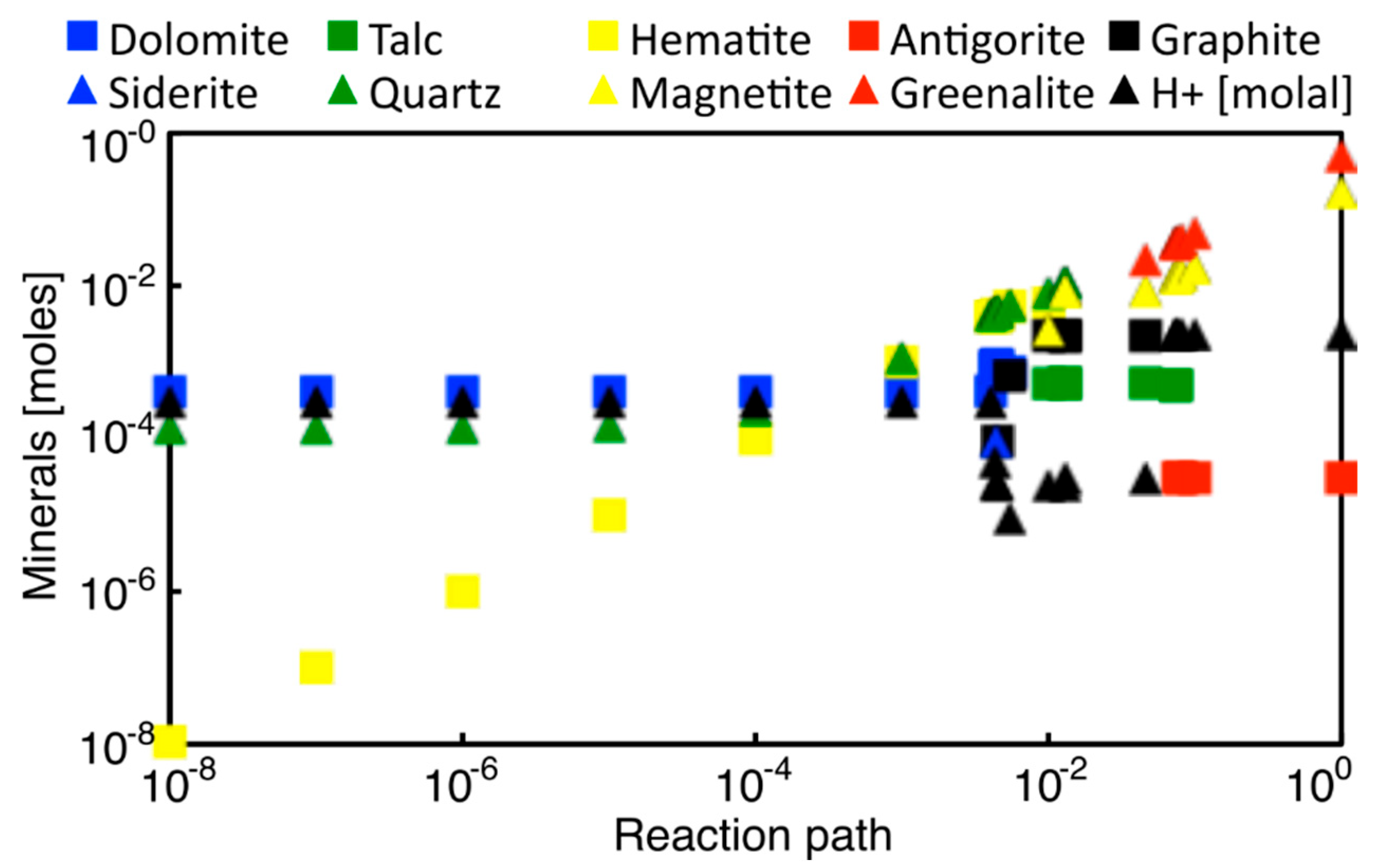

3.3.1. Enceladus

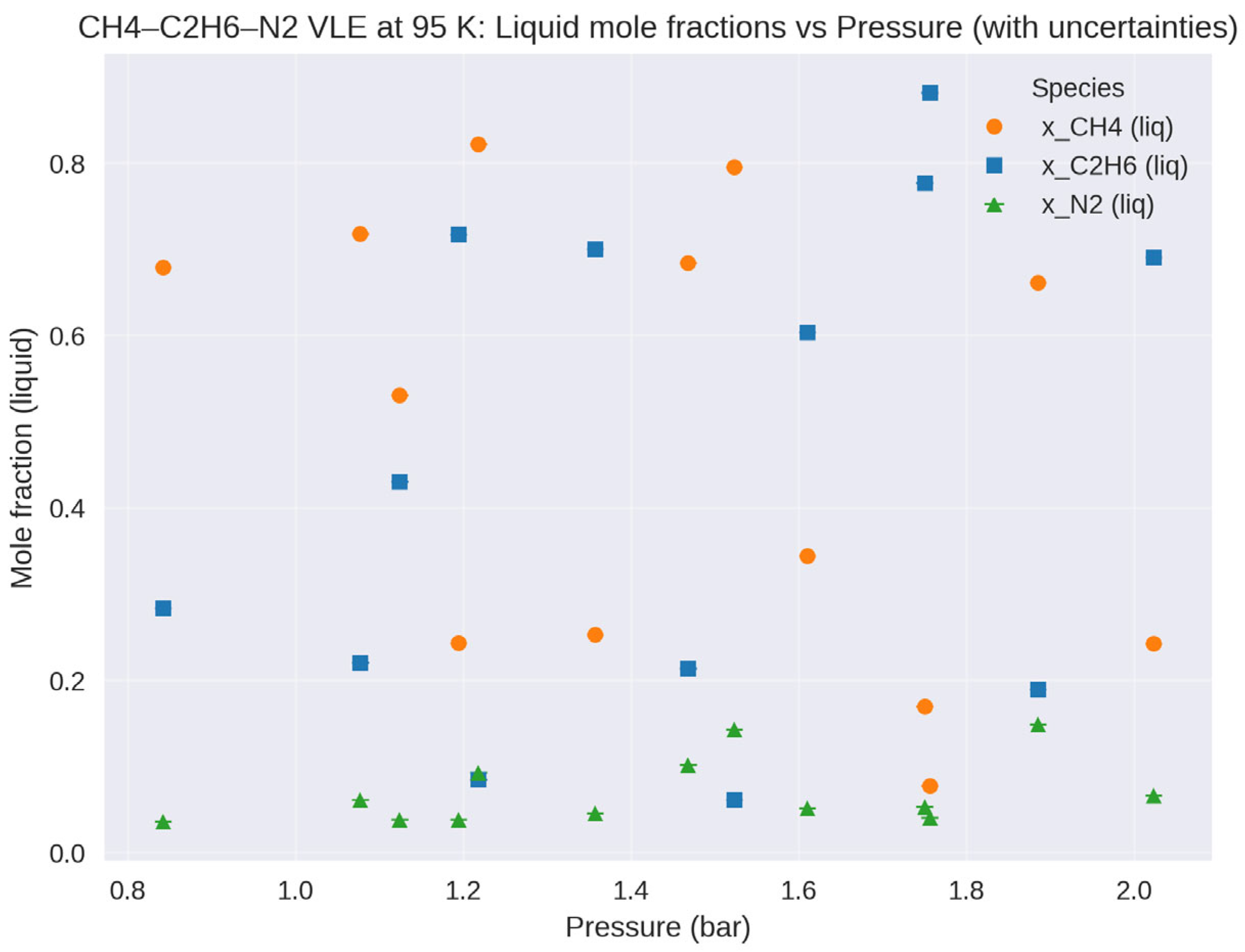

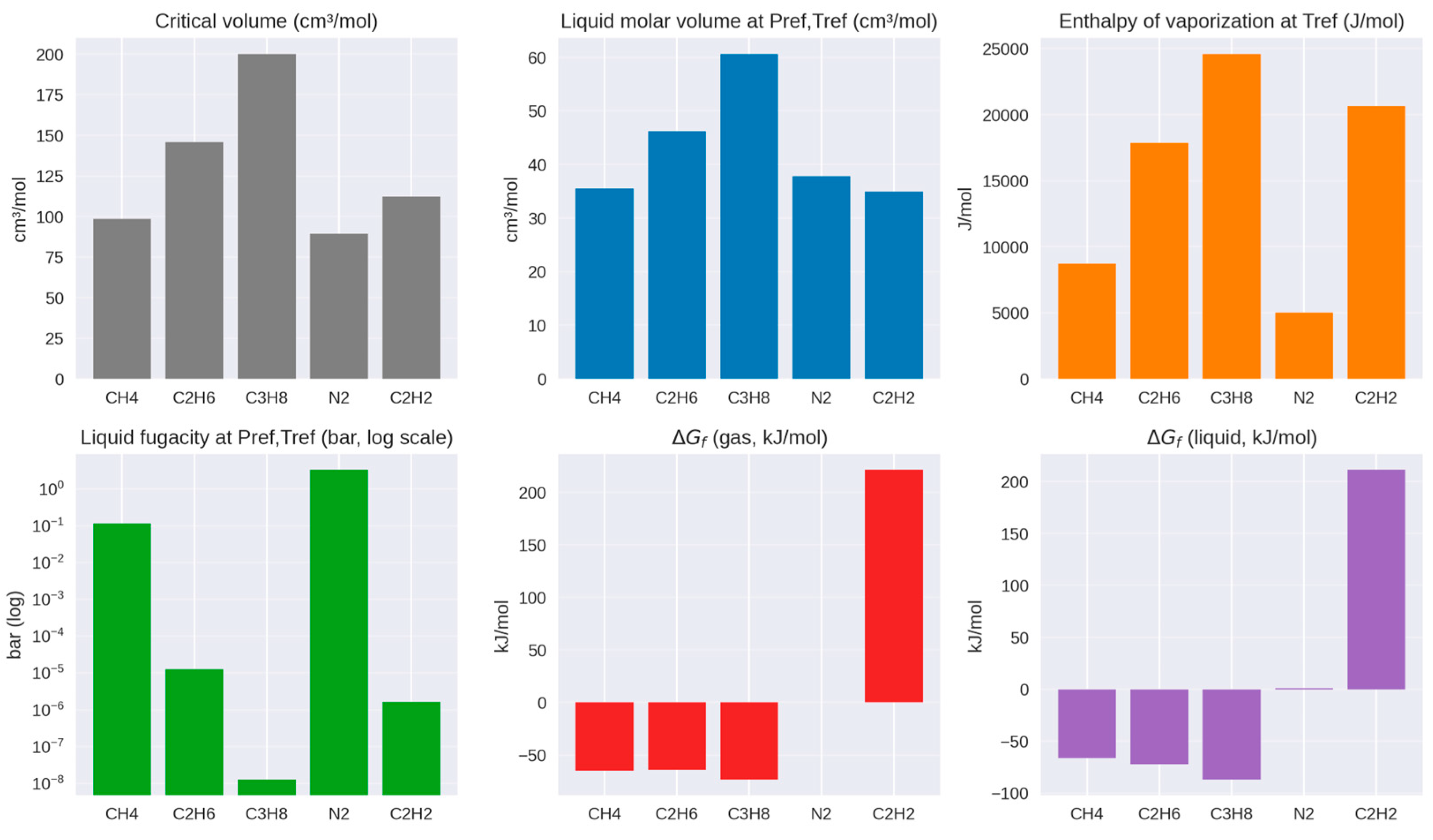

3.3.2. Titan

3.4. Uranus

3.5. Neptune

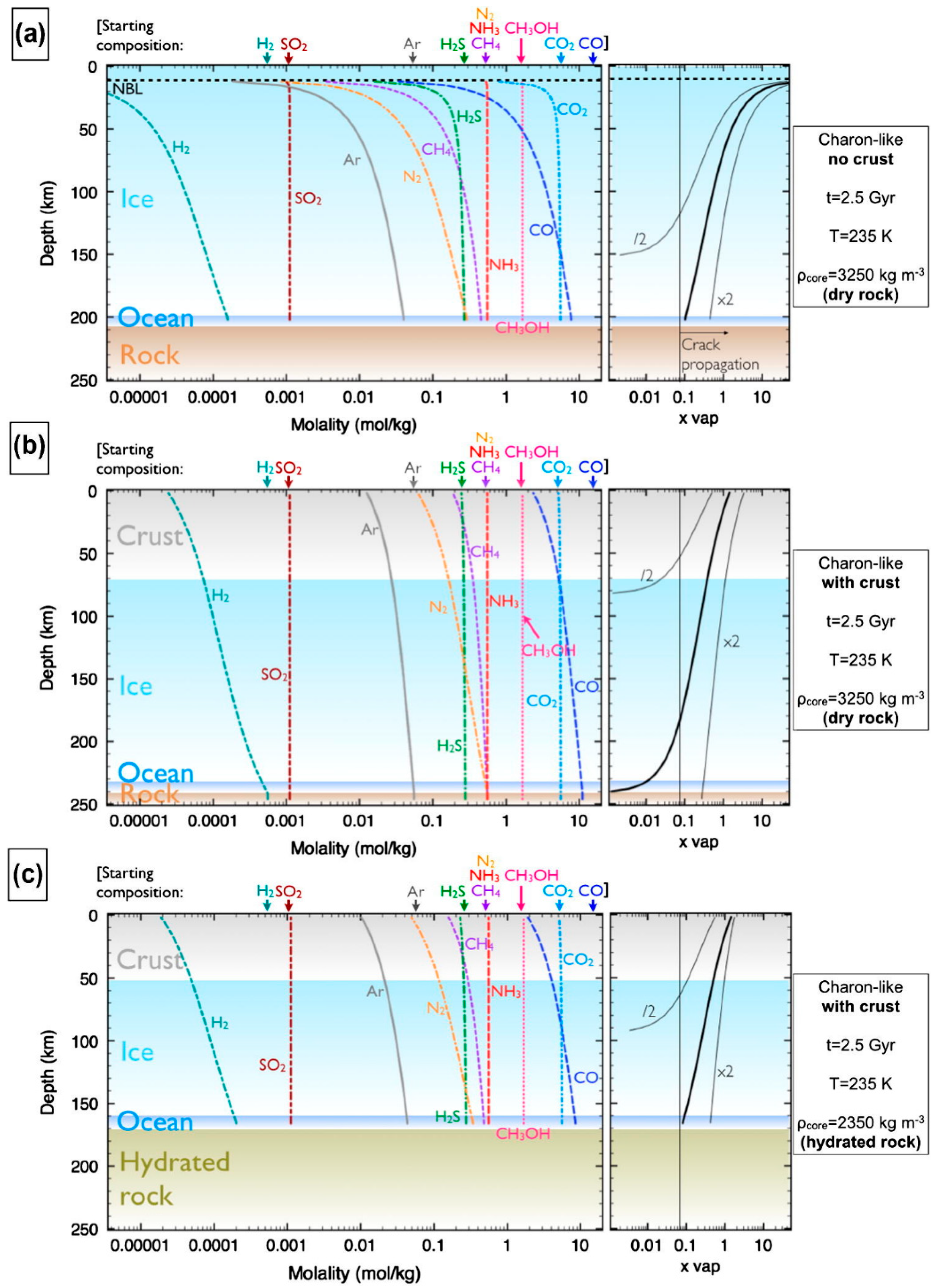

3.6. Pluto

3.7. Synthesis of Reviewed Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Challenges and Solutions

4.2. Prominent Researchers, Journals, and Country Contributions

4.3. Most Studied Celestial Bodies

4.4. Most Popular Methods and Models

4.5. Key Materials and Alien Life Exploration

4.6. Relationship Between Distance and Study Volume

5. Concluding Remarks

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albarède, F. Geochemistry: An Introduction, 5th ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kragh, H. From geochemistry to cosmochemistry: The origin of a scientific discipline, 1915–1955. In Chemical Sciences in the 20th Century: Bridging Boundaries; Reinhold, C., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 160–192. [Google Scholar]

- McSween, H.Y.; Richardson, S.M.; Uhle, M.E.; Richardson, S.M. Geochemistry Pathways and Processes, 2nd ed.; Columbia University: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- McSween, H.Y.J.; Huss, G.R. Cosmochemistry; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- White, W.M. Geochemistry, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C. Geochemical Modelling in Environmental and Geological Studies. In Encyclopedia of Sustainability Science and Technology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 4094–4104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethke, C. Geochemical Reaction Modelling: Concepts and Applications; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Khalidy, R.; Santos, R.M. Assessment of geochemical modelling applications and research hot spots—A year in review. Environ. Geochem. Health 2021, 43, 3351–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.; Anderson, G. Geochemical Modelling. Zhu Laboratory, Indiana University Bloomington. 2023. Available online: https://hydrogeochem.earth.indiana.edu/software/index.html (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Johnson, P.V.; Hodyss, R.; Vu, T.H.; Choukroun, M. Insights into Europa’s ocean composition derived from its surface expression. Icarus 2019, 321, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAU. Pluto and the Solar System; International Astronomical Union (IAU): Paris, France, 2006; Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20230217184727/https://www.iau.org/public/themes/pluto/ (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Beinahegut. The Solar System. Wikimedia Commons. 29 August 2019. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Solar_System.svg (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Williams, D.R. Planetary Fact Sheet. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. 2023. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20230308001412/https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet/ (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Williams, D.R. Planetary Fact Sheet Notes. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. 2021. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20221206024506/https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet/planetfact_notes.html (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- NASA. Jupiter Moons—Overview. NASA Solar System Exploration. 2023. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20230325204005/https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/moons/jupiter-moons/overview/ (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Sheppard, S.S.; Tholen, D.J.; Alexandersen, M.; Trujillo, C.A. New Jupiter and Saturn Satellites Reveal New Moon Dynamical Families. Res. Notes AAS 2023, 7, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigliardi, B.; Filippelli, S. Factors affecting the growth of academic oriented spin-offs. In Innovation Strategies in the Food Industry: Tools for Implementation, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, R.; Güttel, W.H. The dynamic capability view in strategic management: A bibliometric review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 426–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfield, E. KeyWords PIus: ISI’s Breakthrough Retrieval Method. Part 1. Expanding Your Searching Power on Current Contents on Diskette. Curr. Contents 1990, 32, 295–299. Available online: https://garfield.library.upenn.edu/essays/v13p295y1990.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Garfield, E.; Sher, I.H. Key Words Plus [TM]-Algorithmic Derivative Indexing. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1993, 44, 298–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, Q.; Zheng, F.; Long, C.; Lu, Z.; Duan, Z. Comparing keywords plus of WOS and author keywords: A case study of patient adherence research. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 967–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, J.; Daswani, M.M.; Castillo-Rogez, J. Bulk composition and thermal evolution constrain the formation of organics in Ceres’ subsurface ocean via geochemical modelling. Icarus 2023, 391, 115339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Rogez, J.C.; Hesse, M.A.; Formisano, M.; Sizemore, H.; Bland, M.; Ermakov, A.I.; Fu, R.R. Conditions for the Long-Term Preservation of a Deep Brine Reservoir in Ceres. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 1963–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neveu, M.; Desch, S.J.; Shock, E.L.; Glein, C.R. Prerequisites for explosive cryovolcanism on dwarf planet-class Kuiper belt objects. Icarus 2015, 246, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marion, G.M.; Kargel, J.S.; Catling, D.C.; Jakubowski, S.D. Effects of pressure on aqueous chemical equilibria at subzero temperatures with applications to Europa. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2005, 69, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCollom, T.M. Methanogenesis as a potential source of chemical energy for primary biomass production by autotrophic organisms in hydrothermal systems on Europa. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 1999, 104, 30729–30742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.C. Models of Radar Absorption in Europan Ice. Icarus 2000, 147, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marion, G.M.; Mironenko, M.V.; Roberts, M.W. FREZCHEM: A geochemical model for cold aqueous solutions. Comput. Geosci. 2010, 36, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marion, G.M. A molal-based model for strong acid chemistry at low temperatures. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2002, 66, 2499–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCord, T.B.; Teeter, G.; Hansen, G.B.; Sieger, M.T.; Orlando, T.M. Brines exposed to Europa surface conditions. J. Geophys. Res. E Planets 2002, 107, 4-1–4-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, T.M.; McCord, T.B.; Grieves, G.A. The chemical nature of Europa surface material and the relation to a subsurface ocean. Icarus 2005, 177, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daswani, M.M.; Vance, S.D.; Mayne, M.J.; Glein, C.R. A Metamorphic Origin for Europa’s Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2021GL094143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glein, C.R.; Waite, J.H. The Carbonate Geochemistry of Enceladus’ Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2019GL085885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordier, D.; Mousis, O.; Lunine, J.I.; Lavvas, P.; Vuitton, V. An estimate of the chemical composition of Titan’s lakes. Astrophys. J. 2009, 707, L128–L131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postberg, F.; Kempf, S.; Schmidt, J.; Brilliantov, N.; Beinsen, A.; Abel, B.; Buck, U.; Srama, R. Sodium salts in E-ring ice grains from an ocean below the surface of Enceladus. Nature 2009, 459, 1098–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glein, C.R.; Shock, E.L. A geochemical model of non-ideal solutions in the methane-ethane-propane-nitrogen-acetylene system on Titan. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2013, 115, 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, K.J.; Gould, I.R.; Hartnett, H.E.; Williams, L.B.; Shock, E.L. Hydrothermal Experiments with Protonated Benzylamines Provide Predictions of Temperature-Dependent Deamination Rates for Geochemical Modelling. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2021, 5, 1997–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

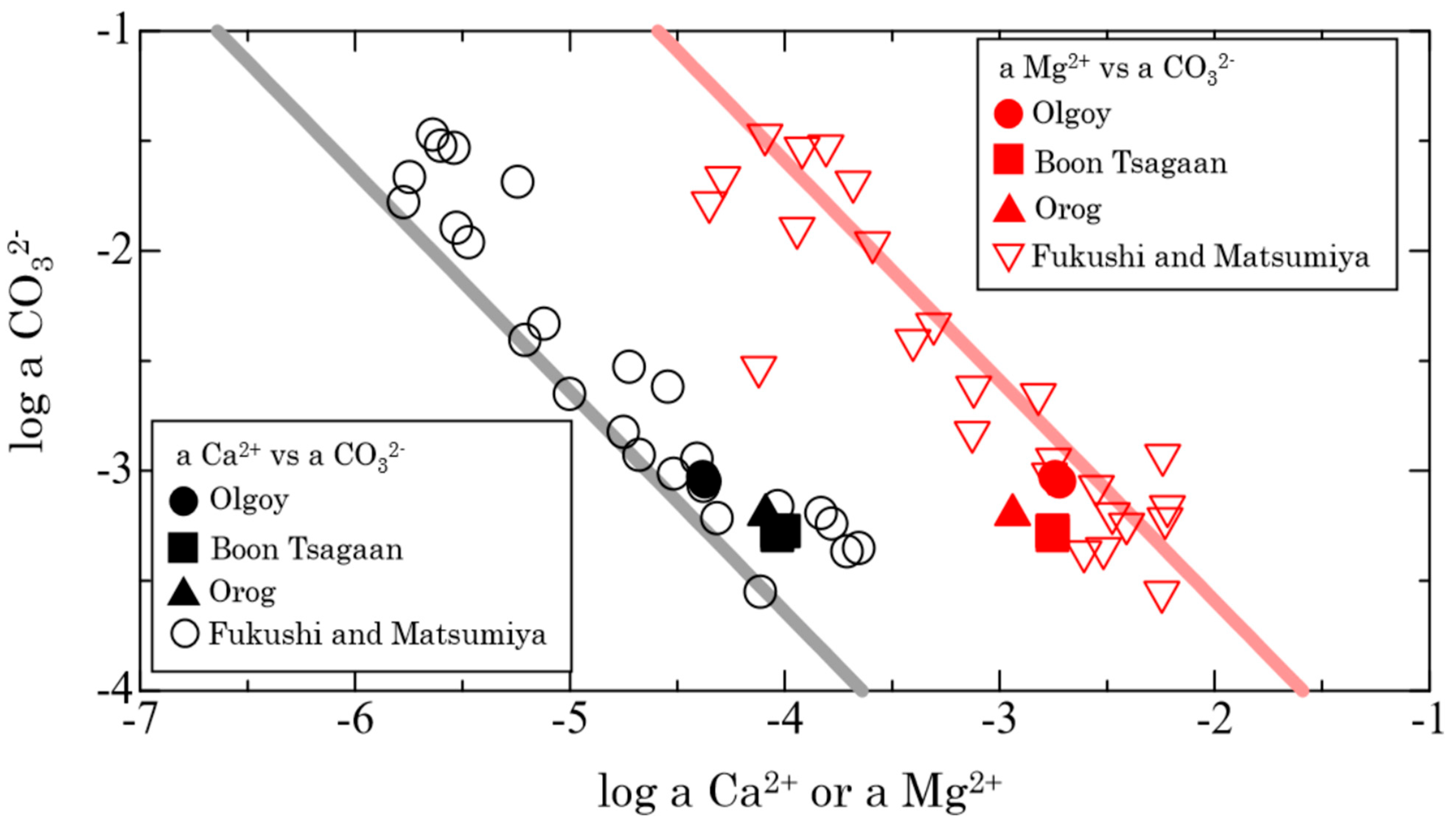

- Fukushi, K.; Imai, E.; Sekine, Y.; Kitajima, T.; Gankhurel, B.; Davaasuren, D.; Hasebe, N. In situ formation of monohydrocalcite in alkaline saline lakes of the valley of gobi lakes: Prediction for mg, ca, and total dissolved carbonate concentrations in enceladus’ ocean and alkaline-carbonate ocean worlds. Minerals 2020, 10, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolotov, M.Y. Aqueous fluid composition in CI chondritic materials: Chemical equilibrium assessments in closed systems. Icarus 2012, 220, 713–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glein, C.R. Noble gases, nitrogen, and methane from the deep interior to the atmosphere of Titan. Icarus 2015, 250, 570–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affholder, A.; Guyot, F.; Sauterey, B.; Ferrière, R.; Mazevet, S. Bayesian Analysis of Enceladus’s Plume Data to Assess Methanogenesis. Nat. Astron. 2021, 5, 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barge, L.M.; White, L.M. Experimentally Testing Hydrothermal Vent Origin of Life on Enceladus and Other Icy/Ocean Worlds. Astrobiology 2017, 17, 820–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassez, M.-P. Follow the High Subcritical Water. Geosciences 2019, 9, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghini, G.; Rampone, E. Postcumulus Processes in Oceanic-Type Olivine-Rich Cumulates: The Role of Trapped Melt Crystallization versus Melt/Rock Interaction. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 2007, 154, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duca, Z.A.; Speller, N.C.; Craft, K.L.; Cable, M.L.; Stockton, A.M. Quantitative and compositional analysis of trace amino acids in icy moon analogues using microcapillary electrophoresis laser-induced fluorescence detection. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2022, 6, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fifer, L.M.; Catling, D.C.; Toner, J.D. Chemical Fractionation Modeling of Plumes Indicates a Gas-Rich, Moderately Alkaline Enceladus Ocean. Planet. Sci. J. 2022, 3, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fones, E.M.; Templeton, A.S.; Mogk, D.W.; Boyd, E.S. Transformation of low-molecular-weight organic acids by microbial endoliths in subsurface mafic and ultramafic igneous rock. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 24, 4137–4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

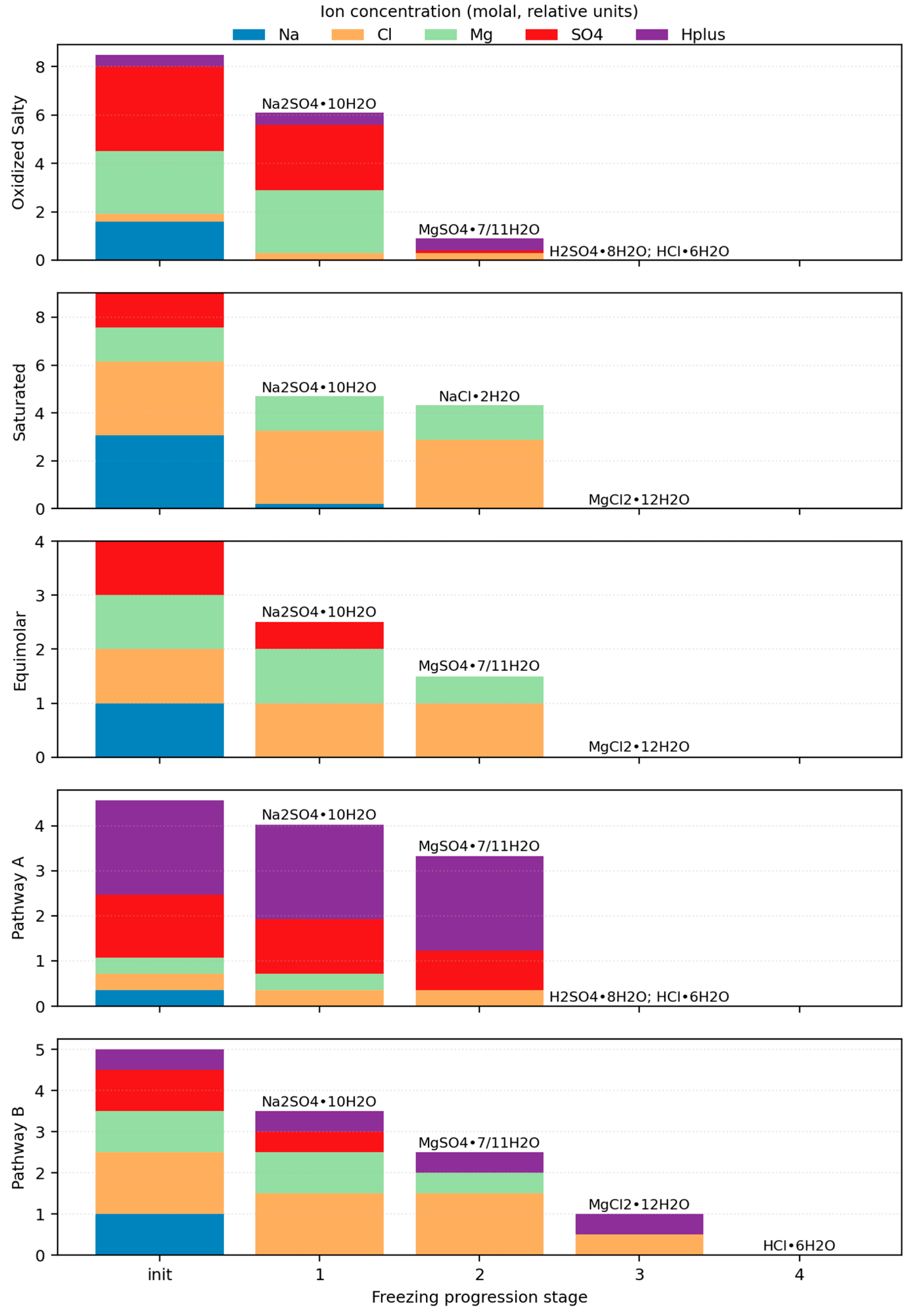

- Fox-Powell, M.G.; Cousins, C.R. Partitioning of Crystalline and Amorphous Phases during Freezing of Simulated Enceladus Ocean Fluids. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2021, 126, e2020JE006628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, P.M.; Glein, C.R.; Cockell, C.S. Instantaneous Habitable Windows in the Parameter Space of Enceladus’ Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2021, 126, e2021JE006951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, S.Q.; Brazelton, W.J. Habitability of the marine serpentinite subsurface: A case study of the Lost City hydrothermal field. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2020, 378, 20180429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunine, J.I.; Hörst, S.M. Organic Chemistry on the Surface of Titan. Rend. Lincei 2011, 22, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marion, G.M.; Kargel, J.S.; Catling, D.C.; Lunine, J.I. Modeling Ammonia–Ammonium Aqueous Chemistries in the Solar System’s Icy Bodies. Icarus 2012, 220, 932–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marusiak, A.G.; Vance, S.; Panning, M.P.; Běhounková, M.; Byrne, P.K.; Choblet, G.; Daswani, M.M.; Hughson, K.; Journaux, B.; Lobo, A.H.; et al. Exploration of Icy Ocean Worlds Using Geophysical Approaches. Planet. Sci. J. 2021, 2, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Iglesias, V.; Prieto-Ballesteros, O. Low-Temperature High-Pressure Chemistry of Ammonia and Methanol Aqueous Solutions in the Presence of Different Carbon Sources: Application to Icy Bodies. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2022, 6, 1482–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neveu, M.; Anbar, A.D.; Davila, A.F.; Glavin, D.P.; MacKenzie, S.M.; Phillips-Lander, C.M.; Sherwood, B.; Takano, Y.; Williams, P.; Yano, H. Returning Samples from Enceladus for Life Detection. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 2020, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanloup, C.; Fei, Y. Closure of the Fe–S–Si Liquid Miscibility Gap at High Pressure. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 2004, 147, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seckbach, J.; Chela-Flores, J. Astrobiology: From Extremophiles in the Solar System to Extraterrestrial Civilizations. In Astronomy and Civilization; Tymieniecka, A.-T., Grandpierre, A., Eds.; Analecta Husserliana, Vol. CVII; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajeddine, R.; Hedman, M.M.; Soderlund, K.M.; Thomas, P.C.; Helfenstein, P.; Hedman, M.M.; Burns, J.A.; Schenk, P.M. True Polar Wander of Enceladus from Topographic Data. Icarus 2017, 295, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theiling, B.P. The Effect of Europa and Enceladus Analog Seawater Composition on Isotopic Measurements of Volatile CO2. Icarus 2021, 358, 114216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Chen, H.; Zong, Q.; Wang, J.; Shi, W.; Zou, H.; Zou, J.; Zhong, W.; Chen, Z.; Shao, S.; et al. Mitigating Deep Dielectric Charging Effects in Space. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2017, 64, 2822–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.; Carney, S.; Boeck, M.; Dunford, B. Ceres in Depth. NASA Solar System Exploration. 23 May 2023. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20230523214232/https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/dwarf-planets/ceres/in-depth/ (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Castillo-Rogez, J.C.; Neveu, M.; Scully, J.E.C.; House, C.H.; Quick, L.C.; Bouquet, A.; Miller, K.; Bland, M.; De Sanctis, M.C.; Ermakov, A.I.; et al. Ceres: Astrobiological Target and Possible Ocean World. Astrobiology 2020, 20, 269–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sanctis, M.C.; Mitri, G.; Castillo-Rogez, J.C.; House, C.H.; Marchi, S.; Raymond, C.A.; Sekine, Y. Relict Ocean Worlds: Ceres. Space Sci. Rev. 2020, 216, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Rogez, J.C.; McCord, T.B. Ceres’ evolution and present state constrained by shape data. Icarus 2010, 205, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA. Jupiter in Depth. NASA Solar System Exploration. 2023. Available online: https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/jupiter/in-depth/ (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- NASA. Jupiter—Overview. NASA Solar System Exploration. 2023. Available online: https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/jupiter/overview/ (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Davis, P.; Carney, S.; Dunford, B.; Boeck, M. Ganymede–Overview. NASA Solar System Exploration. 22 March 2023. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20230326132540/https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/moons/jupiter-moons/ganymede/overview/ (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- NASA. Io—Overview. NASA Solar System Exploration. 2023. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20230325170120/https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/moons/jupiter-moons/io/overview/ (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Davis, P.; Carney, S.; Dunford, B.; Boeck, M. Europa—Overview. NASA Solar System Exploration. 22 March 2023. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20230326040431/https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/moons/jupiter-moons/europa/overview/ (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Carlson, R.W.; Johnson, R.E.; Anderson, M.S. Sulfuric acid on Europa and the radiolytic sulfur cycle. Science 1999, 286, 97–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargel, J.S.; Kaye, J.Z.; Head, J.W.; Marion, G.M.; Sassen, R.; Crowley, J.K.; Ballesteros, O.P.; Grant, S.A.; Hogenboom, D.L. Europa’s Crust and Ocean: Origin, Composition, and the Prospects for Life. Icarus 2000, 148, 226–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, S.D.; Craft, K.L.; Shock, E.; Schmidt, B.E.; Lunine, J.; Hand, K.P.; McKinnon, W.B.; Spiers, E.M.; Chivers, C.; Lawrence, J.D.; et al. Investigating Europa’s Habitability with the Europa Clipper. Space Sci. Rev. 2023, 219, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z.; Shao, N.; Akinyemi, T.; Whitman, W.B. Methanogenesis. Curr. Biol. CB 2018, 28, R727–R732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R. Saturn Fact Sheet. NASA. 2023. Available online: https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet/saturnfact.html (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Davis, P.; Carney, S.; Dunford, B.; Boeck, M. Saturn Moons. NASA Solar System Exploration. 2023. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20230320131033/https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/moons/saturn-moons/overview/?page=0&per_page=40&order=name+asc&search=&placeholder=Enter+moon+name&condition_1=38%3Aparent_id&condition_2=moon%3Abody_type%3Ailike (accessed on 27 January 2026).

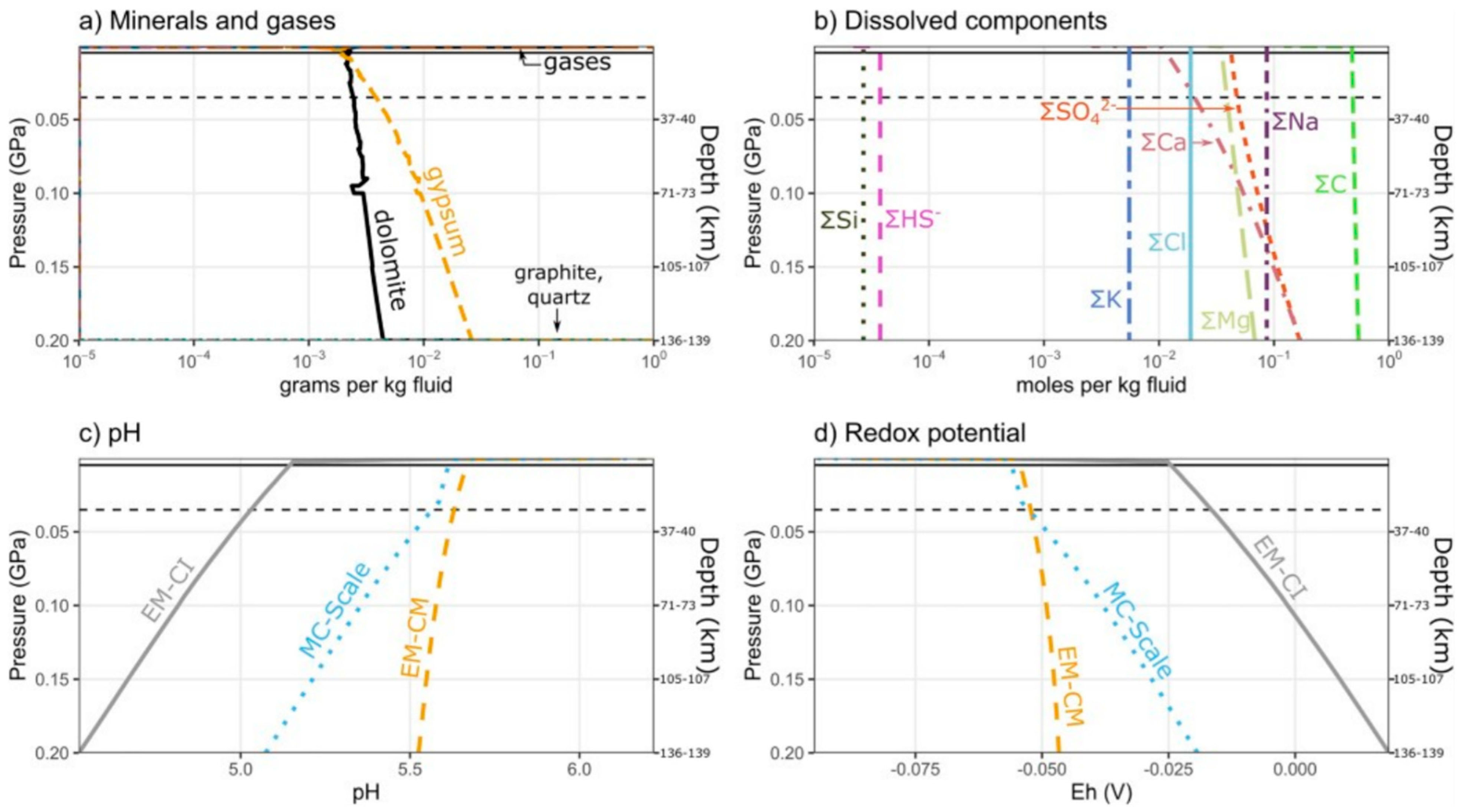

- Glein, C.R.; Baross, J.A.; Waite, J.H. The pH of Enceladus’ ocean. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2015, 162, 202–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

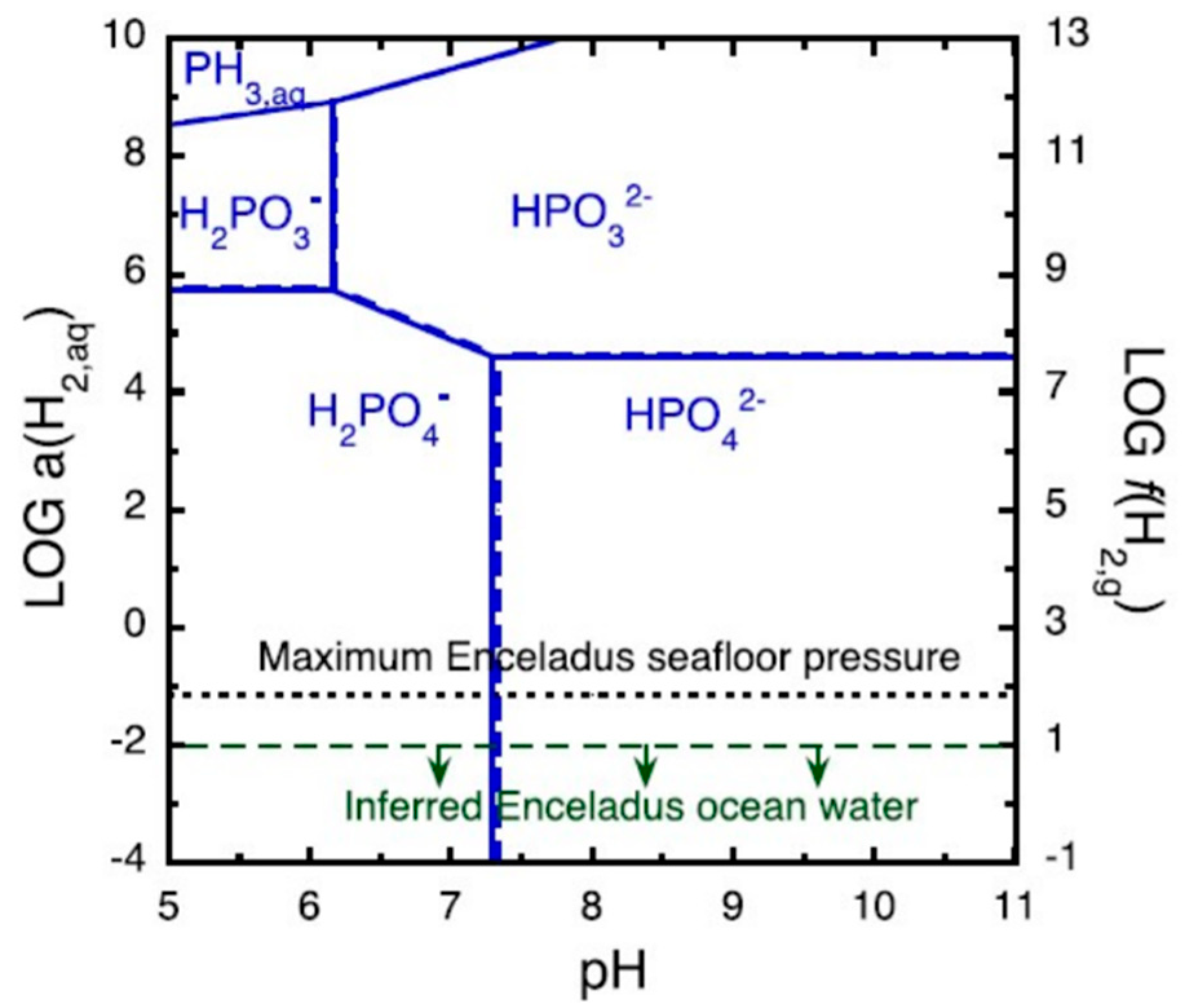

- Hao, J.; Glein, C.R.; Huang, F.; Yee, N.; Catling, D.C.; Postberg, F.; Hillier, J.K.; Hazen, R.M. Abundant phosphorus expected for possible life in Enceladus’s ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2201388119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukushi, K.; Matsumiya, H. Control of Water Chemistry in Alkaline Lakes: Solubility of Monohydrocalcite and Amorphous Magnesium Carbonate in CaCl2-MgCl2-Na2CO3 Solutions. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2018, 2, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, S.B.; Taubner, R.; Leitner, J.J.; Firneis, M.G. On the possibility of Serpentinization on Enceladus. EPSC Abstr. 2015, 10, 644. Available online: https://meetingorganizer.copernicus.org/EPSC2015/EPSC2015-644.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Wolery, T.J. EQ3/6 A Software Package for Geochemical Modelling; Computer Software; U.S. Department of Energy Office of Scientific and Technical Information (USDOE): Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Glein, C.R.; Desch, S.J.; Shock, E.L. The absence of endogenic methane on Titan and its implications for the origin of atmospheric nitrogen. Icarus 2009, 204, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubouloz, N.; Raulin, F.; Lellouch, E.; Gautier, D. Titan’s hypothesized ocean properties: The influence of surface temperature and atmospheric composition uncertainties. Icarus 1989, 82, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lellouch, E.; Coustenis, A.; Gautier, D.; Raulin, F.; Dubouloz, N.; Frère, C. Titan’s atmosphere and hypothesized ocean: A reanalysis of the Voyager 1 radio-occultation and IRIS 7.7-μm data. Icarus 1989, 79, 328–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R. Uranus Fact Sheet. NASA. 2024. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20240923103204/https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet/uranusfact.html (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Ladd, D.; Lentz, M.; Simon, A.A.; Kim, K.; McElligott, J.; Lepsch, A.E. Exploring Planet Uranus. NASA Scientific Visualization Studio. 15 May 2024. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20241001140906/https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/14580 (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- NASA. All About Uranus. NASA Space Place. 2024. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20241001133624/https://spaceplace.nasa.gov/all-about-uranus/en/ (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- NASA. Uranus. NASA Science. 2024. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20241001135248/https://science.nasa.gov/uranus/ (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Fagents, S.A. Considerations for effusive cryovolcanism on Europa: The post-Galileo perspective. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2003, 108, 5139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, I.J.; Turner, D.L.; Kollmann, P.; Clark, G.B.; Hill, M.E.; Regoli, L.H.; Gershman, D.J. A Localized and Surprising Source of Energetic Ions in the Uranian Magnetosphere between Miranda and Ariel. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2022GL101998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.; Carney, S.; Boeck, M.; Dunford, B. Neptune in Depth. NASA Solar System Exploration. 19 May 2023. Available online: https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/neptune/in-depth/ (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Williams, D.R. Neptune Fact Sheet. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. 2023. Available online: https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet/neptunefact.html (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Kirk, R.L.; Soderblom, L.A.; Brown, R.H.; Kieffer, S.W.; Kargel, J.S. Triton’s plumes: Discovery, characteristics, and models. In Neptune and Triton; Cruikshank, D.P., Matthews, M.S., Schumann, A.M., Eds.; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 1995; Volume 1, pp. 949–989. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/publications/tritons-plumes-discovery-characteristics-and-models (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Smith, B.A.; Soderblom, L.A.; Banfield, D.; Barnet, C.; Basilevksy, A.T.; Beebe, R.F.; Bollinger, K.; Boyce, J.M.; Brahic, A.; Briggs, G.A.; et al. Voyager 2 at Neptune: Imaging Science Results. Science 1989, 246, 1422–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, T.; Lellouch, E.; Holler, B.J.; Young, L.A.; Schmitt, B.; Marques Oliveira, J.; Sicardy, B.; Forget, F.; Grundy, W.M.; Merlin, F.; et al. Volatile Transport Modeling on Triton with New Observational Constraints. Icarus 2022, 373, 114764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soderblom, L.A.; Kieffer, S.W.; Becker, T.L.; Brown, R.H.; Cook, A.F.; Hansen, C.J.; Johnson, T.V.; Kirk, R.L.; Shoemaker, E.M. Triton’s Geyser-Like Plumes: Discovery and Basic Characterization. Science 1990, 250, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenberg, T.; Shorttle, O.; Teske, J.; Kempton, E.M.R. Constraining exoplanet interiors using observations of their atmospheres. Science 2025, 390, eads3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glein, C.R.; Yu, X.; Luu, C.N. Deciphering Sub-Neptune Atmospheres: New Insights from Geochemical Models of TOI-270 d. Astrophys. J. 2025, 985, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.; Carney, S. Pluto—Overview. NASA Solar System Exploration. 19 May 2023. Available online: https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/dwarf-planets/pluto/ (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Williams, D.R. Pluto Fact Sheet. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. 2023. Available online: https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet/plutofact.html (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Moore, J.M.; McKinnon, W.B.; Spencer, J.R.; Howard, A.D.; Schenk, P.M.; Beyer, R.A.; Nimmo, F.; Singer, K.N.; Umurhan, O.M.; White, O.L.; et al. The Geology of Pluto and Charon Through the Eyes of New Horizons. Science 2016, 351, 1284–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, D.E.; Sorensen, C.M. The density of supercooled water. II. Bulk samples cooled to the homogeneous nucleation limit. J. Chem. Phys. 1987, 87, 4840–4845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishima, O. Volume of supercooled water under pressure and the liquid-liquid critical point. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 133, 144503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Association for the Properties of Water and Steam. Revised Release on the IAPWS Formulation 1995 for the Thermodynamic Properties of Ordinary Water Substance for General and Scientific Use (2018). IAPWS R6-95(2018). Available online: https://iapws.org/documents/release/IAPWS-95 (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Wagner, W.; Pruß, A. The IAPWS Formulation 1995 for the Thermodynamic Properties of Ordinary Water Substance for General and Scientific Use. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 2002, 31, 387–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holten, V.; Bertrand, C.E.; Anisimov, M.A.; Sengers, J.V. Thermodynamics of supercooled water. J. Chem. Phys. 2012, 136, 094507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolotov, M.Y. An oceanic composition on early and today’s Enceladus. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, 23203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCord, T.B.; Hansen, G.B.; Fanale, F.P.; Carlson, R.W.; Matson, D.L.; Johnson, T.V.; Smythe, W.D.; Crowley, J.K.; Martin, P.D.; Ocampo, A.; et al. Salts on Europa’s surface detected by Galileo’s near infrared map-ping spectrometer. The NIMS Team. Science 1998, 280, 1242–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCord, T.B.; Hansen, G.B.; Clark, R.N.; Martin, P.D.; Hibbitts, C.A.; Fanale, F.P.; Granahan, J.C.; Segura, M.; Matson, D.L.; Johnson, T.V.; et al. Non-water-ice constituents in the surface material of the icy Galilean satellites from the Galileo near-infrared mapping spectrometer investigation. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 1998, 103, 8603–8626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCord, T.B.; Hansen, G.B.; Matson, D.L.; Johnson, T.V.; Crowley, J.K.; Fanale, F.P.; Carlson, R.W.; Smythe, W.D.; Martin, P.D.; Hibbitts, C.A.; et al. Hydrated salt minerals on Europa’s Surface from the Galileo near-infrared mapping spectrometer (NIMS) investigation. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 1999, 104, 11827–11851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, F.; Leblanc, F.; Witasse, O.; Johnson, R.E. Exospheric signatures of alkali abundances in Europa’s regolith. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2009, 36, 12202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leliwa-Kopystyński, J.; Maruyama, M.; Nakajima, T. The Water–Ammonia Phase Diagram up to 300 MPa: Application to Icy Satellites. Icarus 2002, 159, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.H.; Hodyss, R.; Choukroun, M.; Johnson, P.V. Chemistry of frozen sodium–magnesium–sulfate–chloride brines: Implications for surface expression of Europa’s ocean composition. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2016, 816, L26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA; JPL-Caltech; UCLA; MPS; DLR; IDA. Ceres in Color. NASA Solar System Exploration. 2016. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20230523170143/https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/resources/622/ceres-in-color/ (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Andreoli, C.; Braun, H.; Villard, R.; Simon, A.; Wong, M.H.; Garner, R. Hubble Captures Crisp New Portrait of Jupiter’s Storms. NASA. 2020. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/2020/hubble-captures-crisp-new-portrait-of-jupiters-storms (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- NASA. Jupiter’s Moons: Family Portrait. NASA Solar System Exploration. 2007. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20230325143537/https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/resources/2660/jupiters-moons-family-portrait/?category=moons%2Fjupiter-moons_callisto (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Andreoli, C.; Villard, R.; Simon, A.; Wong, M.H.; Garner, R. Hubble Sees Summertime on Saturn. NASA. 2020. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/2020/hubble-sees-summertime-on-saturn (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Sromovsky, L. PIA17306: Keck Telescope Views of Uranus. NASA. 2004. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20240927015204/https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA17306 (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- NASA; JPL. Neptune Full Disk View. NASA Solar System Exploration. 1998. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20230523031947/https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/resources/611/neptune-full-disk-view/?category=planets_neptune (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- NASA; ESA; Showalter, M. (SETI Institute). Neptune’s Moon Hippocamp. NASA Solar System Exploration. 2019. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20230523031938/https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/resources/2289/neptunes-moon-hippocamp/?category=planets_neptune (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- NASA; JPL; USGS. Montage of Neptune and Triton. NASA Solar System Exploration. 1998. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20230523033313/https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/resources/221/montage-of-neptune-and-triton/?category=planets_neptune (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- NASA; JHUAPL; SwRI. Pluto and Charon: Strikingly Different Worlds. NASA Solar System Exploration. 2015. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20230523034715/https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/resources/697/pluto-and-charon-strikingly-different-worlds/ (accessed on 27 January 2026).

| Mercury | Venus | Earth | Mars | Jupiter | Saturn | Uranus | Neptune | Pluto * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass (1024 kg) | 0.33 | 4.87 | 5.97 | 0.642 | 1898 | 568 | 86.8 | 102 | 0.013 |

| Diameter (km) | 4879 | 12,104 | 12,756 | 6792 | 142,984 | 120,536 | 51,118 | 49,528 | 2376 |

| Density (kg/m3) | 5429 | 5243 | 5514 | 3934 | 1326 | 687 | 1270 | 1638 | 1850 |

| Gravity (m/s2) | 3.7 | 8.9 | 9.8 | 3.7 | 23.1 | 9 | 8.7 | 11 | 0.7 |

| Length of Day (hr) | 4222.6 | 2802 | 24 | 24.7 | 9.9 | 10.7 | 17.2 | 16.1 | 153.3 |

| Distance from Sun (106 km) | 57.9 | 108.2 | 149.6 | 228 | 778.5 | 1432 | 2867 | 4515 | 5906.4 |

| Orbital Period (days) | 88 | 224.7 | 365.2 | 687 | 4331 | 10,747 | 30,589 | 59,800 | 90,560 |

| Orbital Velocity (km/s) | 47.4 | 35 | 29.8 | 24.1 | 13.1 | 9.7 | 6.8 | 5.4 | 4.7 |

| Mean Temperature (C) | 167 | 464 | 15 | −65 | −110 | −140 | −195 | −200 | −225 |

| Surface Pressure (bars) | 0 | 92 | 1 | 0.01 | UNKN ** | UNKN ** | UNKN ** | UNKN ** | 0.00001 |

| Number of Moons | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 95 *** | 83 *** | 27 | 15 **** | 5 |

| Ring System | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Magnetic Field | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | UNKN |

| Celestial Body | Moons/Natural Satellites | |

|---|---|---|

| Planets | Mars | Phobos, Deimos |

| Jupiter | Io, Europa, Ganymede, Callisto, Amalthea, Himalia, Elara, Pasiphae, Sinope, Lysithea, Carme, Ananke, Leda, Thebe, Adrastea, Metis, Callirrhoe, Themisto, Megaclite, Taygete, Chaldene, Harpalyke, Kalyke, Iocaste, Erinome, Isonoe, Praxidike, Autonoe, Thyone, Hermippe, Aitne, Eurydome, Euanthe, Euporie, Orthosie, Sponde, Kale, Pasithee, Hegemone, Mneme, Aoede, Thelxinoe, Arche, Kallichore, Helike, Carpo, Eukelade, Cyllene, Kore, Herse, S/2003J19, S/2003J12, S/2003J15, S/2003J16, S/2003J18, S/2010J1, S/2010J2, S/2011J1, S/2011J2, S/2000J11, S/2003J2, S/2003J3, S/2003J4, S/2003J5, S/2003J9, S/2003J10, S/2003J23 | |

| Saturn | Mimas, Enceladus, Tethys, Dione, Rhea, Titan, Hyperion, Iapetus, Phoebe, Janus, Epimetheus, Helene, Telesto, Calypso, Atlas, Prometheus, Pandora, Pan, Methone, Pallene, Polydeuces, Daphnis, Anthe, Aegaeon, Ymir, Paaliaq, Tarvos, Ijiraq, Suttungr, Kiviuq, Mundilfari, Albiorix, Skathi, Erriapus, Siarnaq, Thrymr, Narvi, Aegir, Bebhionn, Bergelmir, Bestla, Farbauti, Fenrir, Fornjot, Hati, Hyrrokkin, Kari, Loge, Skoll, Surtur, Jarnsaxa, Greip, Tarqeq, S/2004S7, S/2004S12, S/2004S13, S/2004S17, S/2006S1, S/2006S3, S/2007S2, S/2007S3 | |

| Uranus | Miranda, Puck, Caliban, Sycorax, Prospero, Setebos, Stephano, Trinculo, Francisco, Margaret, Ferdinand, Perdita, Mab, Cupid, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, Oberon, Miranda, Cordelia, Ophelia, Bianca, Cressida, Desdemona, Juliet, Portia, Rosalind, Belinda | |

| Neptune | Naiad, Thalassa, Despina, Galatea, Larissa, Hippocamp, Proteus, Triton, Nereid, Halimede, Sao, Laomedeia, Psamathe, Neso, S/2004N1 | |

| Dwarf planets | Pluto | Charon, Nix, Hydra, Kerberos, Styx |

| Ceres | - | |

| Category | Keywords/Phrases | Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Concepts | Geochemistry, Astrochemistry, Thermodynamics, Chemical Equilibrium, Geochemical Kinetics, Reaction Kinetics, Geochemical Reaction Paths, Chemical Speciation, Mineral Saturation State, Ionic Strength, Solute Transport | The fundamental concepts of geochemical modeling are critical for understanding how chemical reactions occur in various environments, including those of celestial bodies. |

| Tools and Models | Geochemical Modeling, Geochemical Software, Thermodynamic Databases, Geochemical Data Analysis, FREZCHEM, HKF Model, CHNOSZ, PHREEQC, EQ3/6, GWB, MINTEQ, PHAST | The tools, databases, and models used in geochemical modeling studies. These models and tools are commonly used to understand and predict geochemical processes, and can be applied to a variety of environments, including those of celestial bodies. |

| Geochemical Processes | Geochemical Transport Processes, Mineral Formation, Mineral Dissolution and Precipitation, Weathering Processes, Redox Reactions, Acid–Base Equilibria, Water–Rock Interaction | Geochemical processes and reactions that could be occurring in a geochemical environment, including those of celestial bodies. |

| Advanced Concepts | Sorption Isotherms, Surface Complexation Models, Geochemical Mass Balance, Radiogenic Isotope Geochemistry, Stable Isotope Geochemistry, Trace Element Geochemistry, Geochemical Pathways, Geochemical Cycling | These terms represent more advanced or specific concepts often studied in detailed or advanced geochemical modeling studies. They can be useful for identifying research that delves into these specific areas of interest. |

| Application Areas | Extraterrestrial Hydrology, Planetary Volcanism, Planetary Ices, Contaminant Transport Modeling, Acid Rock Drainage, Environmental Geochemistry, Hydrogeochemistry | While not naming specific celestial bodies, these terms highlight various contexts where geochemical modeling could be applied. They can help identify studies that focus on specific applications relevant to celestial bodies. |

| Ethane (C2H6) | Propane (C3H8) | Methane (CH4) | Hydrogen Cyanide (HCN) | Butene (C4H8) | Butane (C4H10) | Acetylene (C2H2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ~76–79% | ~7–8% | ~5–10% | ~2–3% | ~1% | ~1% | ~1% |

| Surface Temperature | Atmosphere Composition | Ocean Composition | Ocean/Atmosphere CO |

|---|---|---|---|

| 92.5 K | Argon: 0%, Methane: 1.55% | Ethane (C2H6) and heavier alkanes: >90%, Methane (CH4): 7.3%, Nitrogen (N2): 1.8% | 0.25 |

| 101 K | Argon: 17%, Methane: 21.1% | Ethane (C2H6) and higher alkanes: 5%, Methane (CH4): 83.4%; Nitrogen (N2): 6%, Argon (Ar): 5.6% | 11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yoosefdoost, A.; Santos, R.M. Geochemical Modeling from the Asteroid Belt to the Kuiper Belt: Systematic Review. Encyclopedia 2026, 6, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia6020038

Yoosefdoost A, Santos RM. Geochemical Modeling from the Asteroid Belt to the Kuiper Belt: Systematic Review. Encyclopedia. 2026; 6(2):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia6020038

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoosefdoost, Arash, and Rafael M. Santos. 2026. "Geochemical Modeling from the Asteroid Belt to the Kuiper Belt: Systematic Review" Encyclopedia 6, no. 2: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia6020038

APA StyleYoosefdoost, A., & Santos, R. M. (2026). Geochemical Modeling from the Asteroid Belt to the Kuiper Belt: Systematic Review. Encyclopedia, 6(2), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia6020038