Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education: A State-of-the-Art Overview of Pedagogical Integrity, Artificial Intelligence Literacy, and Policy Integration

Definition

1. Introduction

2. A Brief AI History in (Higher) Education

3. AI in Higher Education

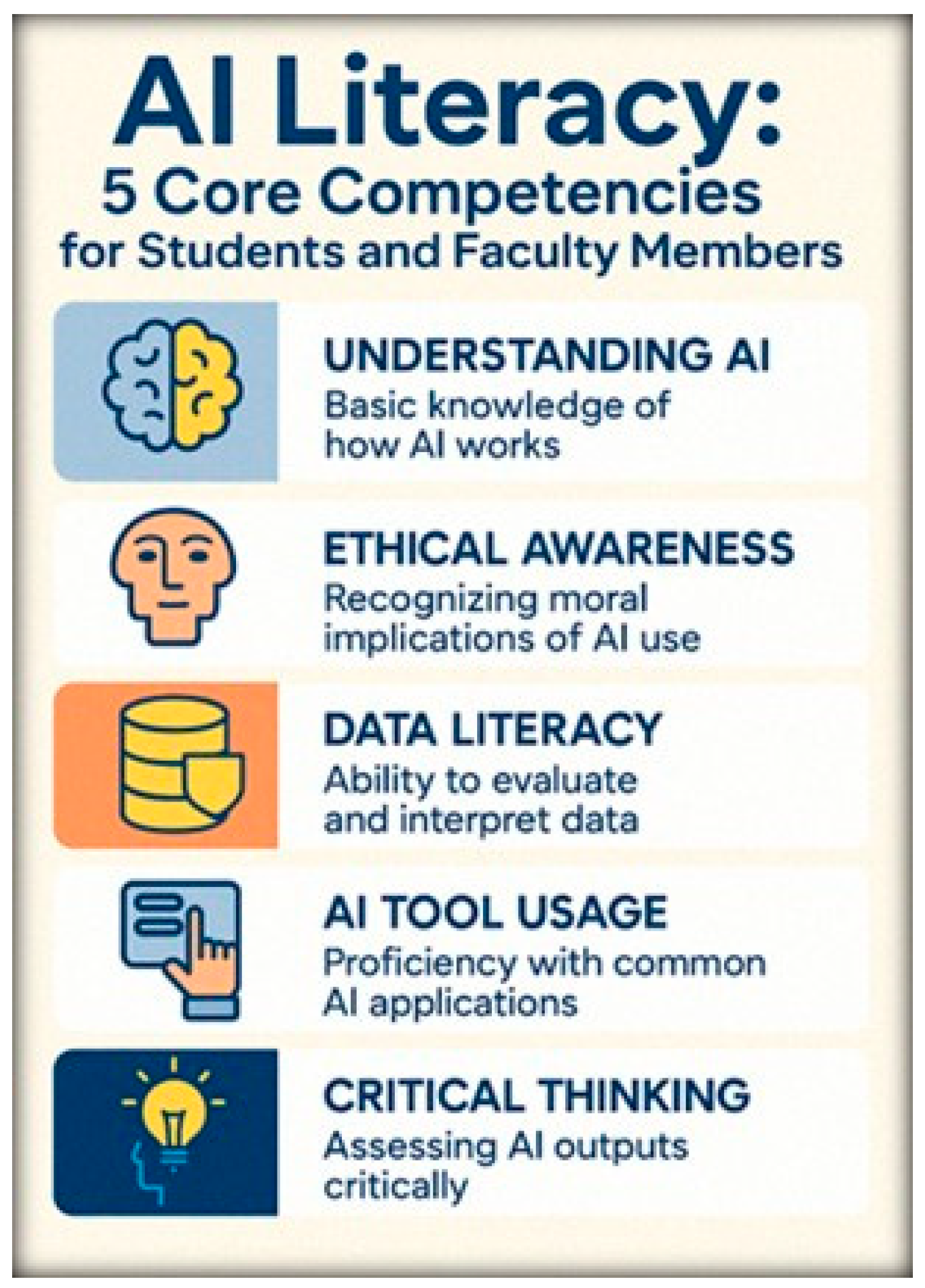

3.1. The Need for AI Literacy in Higher Education

3.2. General Use of AI in Higher Education

3.2.1. Student Uses

3.2.2. Student Evaluation

3.2.3. Academic Writing

3.2.4. Ethical and Institutional Dilemmas

3.3. Teaching, Learning and Assessment Performance and Improvement

3.3.1. Pedagogical Mechanisms, Personalization, and Higher-Order Learning

3.3.2. The Need for Causal Evidence and Methodological Limits

3.3.3. Neurocognitive Considerations and Cognitive Debt

3.3.4. Metacognition, Self-Regulated Learning, and Disciplinary Variation

3.3.5. Motivation, Autonomy, and Design Caveats

3.3.6. Institutional Exemplars and Research Workflows

4. AI Tools for Educators and Teaching Staff in Higher Education (with Examples)

4.1. The Importance of Responsible Tool Selection

4.2. Literature Review and Scientific Mapping

4.3. Personalized Teaching and Instructional Design

4.4. Assessment and Feedback

4.5. Organization and Administrative Management

4.6. Reflective Teaching Support

5. Ethical Use of AI in Teaching, Learning, Course Design, and Assessment

5.1. Institutional and Publishing Policies

5.2. Detection, Fairness, and Disclosure-by-Design

5.3. International Frameworks and Equity Considerations

5.4. Assessment Reform and Adaptive Governance

6. Institutional Integration of AI in Higher Education: Policy Recommendations and Strategic Implementation

6.1. Policy and Governance

6.2. Literacy and Capacity Building

6.3. Curriculum, Assessment, and Academic Integrity

6.4. Infrastructure, Data Protection, and Collaboration

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

- 1.

- Academic Integrity

- 2.

- AI Literacy Development

- 3.

- Pedagogical Integration

- 4.

- Institutional and Policy Adaptation

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| GenAI | Generative Artificial Intelligence |

| LLMs | Large Language Models |

| LMS | Learning management systems |

| ITS | Intelligent Tutoring Systems |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

References

- Liu, Y.; Han, T.; Ma, S.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y. Summary of ChatGPT-Related Research and Perspective Towards the Future of Large Language Models. Meta-Radiology 2023, 1, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrelly, T.; Baker, N. Generative Artificial Intelligence: Implications and Considerations for Higher Education Practice. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.; Calhoun, A.; Reedy, G. Artificial Intelligence–Assisted Academic Writing: Recommendations for Ethical Use. Adv. Simul. 2025, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, F.; Porter, M.; Rinella Fitzgerald, D. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education. Ir. J. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishavan, H.B. AI in Higher Education. In 2024: ASCILITE 2024 Conference Proceedings; The University of Melbourne: Melbourne, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, H.; Burke, D. Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education: The State of the Field. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2023, 20, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempere, J.; Modugu, K.; Hesham, A.; Ramasamy, L.K. The Impact of ChatGPT on Higher Education. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 1206936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fan, W. The Effect of ChatGPT on Students’ Learning Performance, Learning Perception, and Higher-Order Thinking: Insights from a Meta-Analysis. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, R.; Jiang, M.; Yu, X.; Lu, Y.; Liu, S. Does ChatGPT Enhance Student Learning? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Experimental Studies. Comput. Educ. 2025, 227, 105224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganjavi, C.; Eppler, M.B.; Pekcan, A.; Biedermann, B.; Abreu, A.; Collins, G.S.; Gill, I.S.; Cacciamani, G.E. Publishers’ and Journals’ Instructions to Authors on Use of Generative AI in Academic and Scientific Publishing: Bibliometric Analysis. BMJ 2024, 384, e077192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazari, S. Justification and Roadmap for Artificial Intelligence (AI) Literacy Courses in Higher Education. J. Educ. Res. Pract. 2024, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashishth, T.K.; Sharma, V.; Sharma, K.K.; Kumar, B. Enhancing Literacy Education in Higher Institutions with AI: Opportunities and Challenges. In Advances in Educational Technologies and Instructional Design; IGI Global: Palmdale, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 198–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajani, O.A.; Akintolu, M.; Afolabi, S.O. The Emergence of Artificial Intelligence in the Higher Education. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrah, A.M.; Wardat, Y.; Fidalgo, P. Using ChatGPT in Academic Writing Is (Not) a Form of Plagiarism: What Does the Literature Say? Online J. Commun. Media Technol. 2023, 13, e202346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahani, M.S.; Ghasmi, G. Artificial Intelligence in Education: A Comprehensive Study. Forum Educ. Stud. 2024, 2, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conati, C.; Gertner, A.; VanLehn, K. Using Bayesian Networks to Manage Uncertainty in Student Modeling. User Model. User-Adap. Interact. 2002, 12, 371–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conati, C.; Maclaren, H. Empirically Building and Evaluating a Probabilistic Model of User Affect. User Model. User-Adap. Interact. 2009, 19, 267–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckin, R.; Holmes, W. Intelligence Unleashed: An Argument for AI in Education; UCL Knowledge Lab: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dargue, B.; Biddle, E. Just Enough Fidelity in Student and Expert Modeling for ITS. In International Conference on Augmented Cognition; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sleeman, D.H.; Brown, J.S. Intelligent tutoring systems: An overview. In Intelligent Tutoring Systems; Sleeman, D.H., Brown, J.S., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Graesser, A.C.; Chipman, P.; Haynes, B.C.; Olney, A. AutoTutor: An Intelligent Tutoring System with Mixed-Initiative Dialogue. IEEE Trans. Educ. 2005, 48, 612–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanLehn, K.; Graesser, A.C.; Jackson, G.T.; Jordan, P.; Olney, A.; Rosé, C.P. When are tutorial dialogues more effective than reading? Cogn. Sci. 2007, 31, 3–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spector, J.; Merrill, M.; David, M. Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology, 3rd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, H.; Song, D. The Potential of Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education. Rev. Virtual Univ. Católica Norte 2021, 62, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A.; Polepeddi, L. Jill Watson: A Virtual Teaching Assistant for Online Education. Georgia Institute of Technology Research Report. 2018. Available online: https://dilab.gatech.edu/test/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/GoelPolepeddi-DedeRichardsSaxberg-JillWatson-2018.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Abdurohman, N.R. Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education: Opportunities and Challenges. Eurasian Sci. Rev. 2025, 2, 1683–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betül, C.; Durgut, G. AI Literacy in Higher Education: Knowledge, Skills, and Competences; Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE): Waynesville, NC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/224519 (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- AI and the Future of Learning: Expert Panel Report; Roschelle, J., Lester, J., Fusco, J., Eds.; Digital Promise: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://circls.org/reports/ai-report (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- EDUCAUSE. Defining AI Literacy for Higher Education; EDUCAUSE: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.educause.edu/content/2024/ai-literacy-in-teaching-and-learning/defining-ai-literacy-for-higher-education (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Zhang, B.; Dafoe, A. Artificial Intelligence: American Attitudes and Trends; Center for the Governance of AI, University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2019; Available online: https://governanceai.github.io/US-Public-Opinion-Report-Jan-2019/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Long, D.; Magerko, B. What Is AI Literacy? Competencies and Design Considerations. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Media and Information Literacy in the Global South: Politics, Policies and Pedagogies; Ragnedda, M., Mutsvairo, B., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mackey, T.P.; Jacobson, T.E. Metaliteracy: Reinventing Information Literacy to Empower Learners; ALA Neal-Schuman: Chicago, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Touretzky, D.S.; Gardner-McCune, C.; Martin, F.; Seehorn, D. Envisioning AI for K-12: What Should Every Child Know about AI? Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2019, 33, 9795–9799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurt, E. The Self-Regulation for AI-Based Learning Scale: Psychometric Properties and Validation. Int. J. Curr. Educ. Stud. 2025, 4, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şanlı, C. Artificial Intelligence in Geography Teaching: Potentialities, Applications, and Challenges. Int. J. Curr. Educ. Stud. 2025, 4, 47–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodafinos, A. The Integration of Generative AI Tools in Academic Writing: Implications for Student Research. Soc. Educ. Res. 2025, 6, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmyna, N.; Hauptmann, E.; Yuan, Y.T.; Situ, J.; Liao, X.-H.; Beresnitzky, A.V.; Braunstein, I.; Maes, P. Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt When Using an AI Assistant for Essay Writing Task. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.08872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, C.R. Awareness of Artificial Intelligence (AI) among Undergraduate Students. NPRC J. Multidiscip. Res. 2024, 1, 126–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskandarova, S.; Yusif-Zada, K.; Mukhtarova, S. Integrating AI into Higher Education Curriculum in Developing Countries. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), Washington, DC, USA, 13–16 October 2024; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittle, K.; El Gayar, O. Generative AI and Academic Integrity in Higher Education: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Information 2025, 16, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gander, T.; Harris, G. Understanding AI Literacy for Higher Education Students: Implications for Assessment. AI High. Educ. Symp. 2024, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, L. ChatGPT and Academic Integrity Concerns: Detecting Artificial Intelligence Generated Content. Lang. Educ. Technol. 2023, 3, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kudiabor, H. How AI-Powered Science Search Engines Can Speed Up Your Research. Nature 2024, 621, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollick, E.; Mollick, L. Assigning AI: Seven Approaches for Students, with Prompts. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.10052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takona, J.P. AI in Education: Shaping the Future of Teaching and Learning. Int. J. Curr. Educ. Stud. 2024, 3, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jereb, E.; Urh, M. The Use of Artificial Intelligence among Students in Higher Education. Organizacija 2024, 57, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Xuwei, Z. Integration of AI with Higher Education Innovation: Reforming Future Educational Directions. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2023, 12, 1727–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, P.H.; Moss, H.K.; Garger, J. A Synthesis of AI in Higher Education: Shaping the Future. J. Behav. Appl. Manag. 2024, 25, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crain, C.; Ewing, A.; Billy, I.; Anush, H. The Advantages and Disadvantages of AI in Higher Education. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2025, 15, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, M.T.; Humphries, J.; Slater, J. ChatGPT Is Bullshit. Ethics Inf. Technol. 2024, 26, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnakumar, M.; Balasubramanian, K. Effectiveness of AI in Enhancing Quality Higher Education: A Survey Study. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.M.; Shaaban, T.S.; Bakry, S.H.; Guillén-Gámez, F.D.; Strzelecki, A. Empowering the Faculty of Education Students: Applying AI’s Potential for Motivating and Enhancing Learning. Innov. High. Educ. 2024, 50, 587–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasneci, E.; Seßler, K.; Küchemann, S.; Bannert, M.; Dementieva, D.; Fischer, F.; Gasser, U.; Groh, G.; Günnemann, S.; Hüllermeier, E.; et al. ChatGPT for Good? On Opportunities and Challenges of Large Language Models for Education. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2023, 103, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajja, R.; Sermet, Y.; Cikmaz, M.; Cwiertny, D.; Demir, I. Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Intelligent Assistant for Personalized and Adaptive Learning in Higher Education. Information 2024, 15, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msambwa, M.M.; Wen, Z.; Daniel, K. The Impact of AI on the Personal and Collaborative Learning Environments in Higher Education. Eur. J. Educ. 2025, 60, e12909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez-García, L. AI-Based Applications Enhancing Computer Science Teaching in Higher Education. J. Inf. Syst. Eng. Manag. 2025, 10, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasgarova, R.; Rzayev, J. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Shaping High School Students’ Motivation. Int. J. Technol. Educ. Sci. 2024, 8, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, W. The Impact of AI Usage on University Students’ Willingness for Autonomous Learning. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lyu, X. Assessment of the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on College Student Learning Based on the CRITIC Method. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Education, Applications and Standards of Converging Technologies (EASCT), Lonavla, India, 7–9 April 2023; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumbal, A.; Sumbal, R.; Amir, A. Can ChatGPT-3.5 Pass a Medical Exam? A Systematic Review of ChatGPT’s Performance in Academic Testing. J. Med. Educ. Curric. Dev. 2024, 11, 23821205241238641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prillaman, M. Is ChatGPT Making Scientists Hyper-Productive? The Highs and Lows of Using AI. Nature 2024, 627, 16–17. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-00592-w (accessed on 3 August 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. OECD Digital Education Outlook 2023: Towards an Effective Digital Education Ecosystem; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Empowering Learners for the Age of AI: An AI Literacy Framework for Primary and Secondary Education; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2025; Available online: https://ailiteracyframework.org (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Kankam, M.; Nazari, E.; Owan, H.D. Artificial Intelligence Tools in Higher Education Institutions: Review of Adoption and Impact. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owan, H.D.; Akinwalere, T.K.; Ivanov, V. AI tools for motivation, engagement and performance in higher education. Learn. Anal. J. 2023, 9, 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Cacicio, S.; Riggs, R. ChatGPT: Leveraging AI to Support Personalized Teaching and Learning. Adult Lit. Educ. 2023, 5, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.K.Y.; Tsi, L.H.Y. Will Generative AI Replace Teachers in Higher Education? A Study of Teacher and Student Perceptions. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2024, 83, 101395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.A.; Hassan, H.; Nassef, M. Automated Language Essay Scoring Systems: A Literature Review. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2019, 5, e208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burrows, S.; Gurevych, I.; Stein, B. The Eras and Trends of Automatic Short Answer Grading. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2015, 25, 60–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grévisse, C. LLM-Based Automatic Short Answer Grading in Undergraduate Medical Education. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobler, S. Smart Grading: A Generative AI-Based Tool for Knowledge-Grounded Answer Evaluation in Educational Assessments. MethodsX 2024, 12, 102345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, R.; Merzdorf, H.E.; Anwar, S.; Hipwell, M.C.; Srinivasa, A.R. Automatic Assessment of Text-Based Responses in Post-Secondary Education: A Systematic Review. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2024, 6, 100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C.D.; Kay, R.H. A Systematic Review of the Perusall Application: Exploring the Benefits and Challenges of Social Annotation Technology in Higher Education. In INTED 2024 Proceedings; IATED: Valencia, Spain, 2024; pp. 5829–5839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instructure. Instructure and OpenAI Announce Global Partnership to Embed AI Learning Experiences Within Canvas. Instructure, 2025. Available online: https://www.instructure.com/press-release/instructure-and-openai-announce-global-partnership-embed-ai-learning-experiences (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Kofinas, A.K.; Tsay, C.H.-H.; Pike, D. The Impact of Generative AI on Academic Integrity of Authentic Assessments within a Higher Education Context. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2025, 56, e13585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlich, M. AI Tools in Society: Impacts on Cognitive Offloading and the Future of Critical Thinking. Societies 2025, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford Report. AI-Assisted Productivity Tools in Higher Education: Trends and Recommendations; Stanford University Publications: Stanford, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.; Jansen, T.; Schiller, R.; Liebenow, L.W.; Steinbach, M.; Horbach, A.; Fleckenstein, J. Using LLMs to Bring Evidence-Based Feedback into the Classroom: AI-Generated Feedback Increases Secondary Students’ Text Revision, Motivation, and Positive Emotions. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2024, 6, 100199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MentalUP. Top 15 AI Grading Tools for Teachers in 2025; MentalUP: London, UK, 2025; Available online: https://www.mentalup.co/blog/ai-grading-tools-for-teachers (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Jeon, J.; Lee, S. Large Language Models in Education: A Focus on the Complementary Relationship between Human Teachers and ChatGPT. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 15873–15892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber-Wulff, D.; Anohina-Naumeca, A.; Bjelobaba, S.; Foltýnek, T.; Guerrero-Dib, J.; Popoola, O.; Šigut, P.; Waddington, L. Testing of Detection Tools for AI-Generated Text. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 2023, 19, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer Nature. Why AI Writing Detectors Fall Short: Scientific Critique of Detection Tools; Springer White Papers; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- University of Pittsburgh Teaching Center. Why We Disabled AI Detection in Turnitin. 2024. Available online: https://teaching.pitt.edu (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- UNESCO. Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Teaching and Learning: Insights and Recommendations. UNESCO Report. 2023. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000386351 (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE). Guidance for Editors: AI Tools and Authorship; COPE: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://publicationethics.org (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Moya, B.; Eaton, S.E.; Pethrick, H.; Hayden, K.A.; Brennan, R.; Wiens, J.; McDermott, B.; Lesage, J. Academic Integrity and Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education Contexts: A Rapid Scoping Review. Can. Perspect. Acad. Integr. 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallu, S.; Raehang, R.; Qammaddin, Q. Exploration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) Application in Higher Education. J. Comput. Netw. Arch. High Perform. Comput. 2024, 6, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodzi, Z.; Rahman, A.A.; Razali, I.N.B.; Nazri, I.S.B.M.; Abd Gani, A.F. Unraveling the Drivers of Artificial Intelligence (AI) Adoption in Higher Education. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on University Teaching and Learning (InCULT) 2023, Shah Alam, Malaysia, 18–19 October 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Artificial Intelligence Needs Assessment Survey—Africa; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/unesco-launches-findings-artificial-intelligence-needs-assessment-survey-africa (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Bozkurt, A.; Hollands, F.; Mishra, S. AI Teaching and Learning Manifesto: A Global Vision; UNESCO Institute for Information Technologies in Education: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt, A.; Xiao, J.; Farrow, R.; Bai, J.Y.; Nerantzi, C.; Moore, S.; Dron, J.; Stracke, C.M.; Singh, L.; Crompton, H.; et al. The Manifesto for Teaching and Learning in a Time of Generative AI: A Critical Collective Stance to Better Navigate the Future. Open Prax. 2024, 16, 487–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariam, G.; Adil, L.; Zakaria, B. The Integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into Education Systems and Its Impact on the Governance of Higher Education Institutions. Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev. 2024, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Yu, J.H.; James, S. Investigating Higher Education Institutions’ Guidelines and Policies on Generative AI. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2025, 22, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlaif, Z.N. Redesigning Assessments for AI-Enhanced Learning. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlaif, Z. Rethinking Educational Assessment in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. In Fostering Inclusive Education with AI and Emerging Technologies; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adamakis, M.; Rachiotis, T. Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education: A State-of-the-Art Overview of Pedagogical Integrity, Artificial Intelligence Literacy, and Policy Integration. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5040180

Adamakis M, Rachiotis T. Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education: A State-of-the-Art Overview of Pedagogical Integrity, Artificial Intelligence Literacy, and Policy Integration. Encyclopedia. 2025; 5(4):180. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5040180

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdamakis, Manolis, and Theodoros Rachiotis. 2025. "Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education: A State-of-the-Art Overview of Pedagogical Integrity, Artificial Intelligence Literacy, and Policy Integration" Encyclopedia 5, no. 4: 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5040180

APA StyleAdamakis, M., & Rachiotis, T. (2025). Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education: A State-of-the-Art Overview of Pedagogical Integrity, Artificial Intelligence Literacy, and Policy Integration. Encyclopedia, 5(4), 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5040180