Definition

This entry provides a detailed examination of the relationship between education and employment outcomes. It presents the conceptual framework which connects them and discusses the theories on their nexus, and is the first study to attempt this endeavor. Moreover, it analyzes the factors which influence the education–employment relationship, which the existing literature has not comprehensively addressed. In addition, this entry employs data from Eurostat which points to a beneficial role of education on employment, especially of tertiary education. The entry also highlights the role of factors such as the quality and relevance of education, the development of employability skills, the selection and matching processes in the labor market, and the broader economic and social contexts. Within this framework, policymakers should prioritize investments in education and training programs that align with labor market needs, promote both general and vocational skills development, and foster closer collaboration between educational institutions and employers.

1. Introduction

Education and employment are two fundamental pillars of economic and social development, intricately linked in shaping the trajectory of individuals and societies. Education is a key tool for equipping individuals with knowledge and skills. These competencies enhance both employability and productivity in the labor market [1,2,3]. Employment, in turn, provides financial stability, career growth, and social mobility, reinforcing the role of education as a key driver of economic success [4,5]. The connection between education and employment has been widely studied across various academic disciplines, including economics, sociology, and labor studies, reflecting its significance in policy formulation and workforce planning [6,7,8,9].

Numerous studies have highlighted the significant impact of educational attainment on employment outcomes [10,11]. Higher levels of education are associated with increased probabilities of employment, better job quality, higher earnings, and better prospects and outcomes in the labor market [12,13,14]. This is because education provides individuals with the knowledge, skills, and credentials that are in high demand in the labor market. Furthermore, education can have indirect effects on employment by improving individuals’ health, strengthening social networks, and enhancing cognitive abilities, thereby fostering greater employability and labor market success [15]. However, access to these benefits is not equally distributed. Education systems often reflect and reproduce existing social inequalities, favoring individuals from more privileged backgrounds while marginalizing others. As a result, unequal access to quality education can exacerbate disparities in health, social capital, and cognitive development, ultimately hindering employment opportunities for disadvantaged groups and reinforcing cycles of exclusion and economic vulnerability. Understanding the complex interplay between education and employment is crucial for informing effective policies and programs aimed at promoting economic and social well-being.

The existing literature suggests that the relationship between education and employment is not straightforward, and various factors can influence this dynamic [16]. For instance, the selection of educated individuals for more effective training programs can contribute to their higher employability, rather than education itself. Additionally, the educational process, including information construction, teaching reform, and employment guidance provided by educational institutions, can have a significant impact on students’ employment outcomes [17]. Studies have also shown that the strength of the education–employment link varies across countries, with gender norms and sociocultural factors playing a crucial role in moderating this relationship. In some contexts, higher levels of education may not translate into commensurate employment opportunities, due to factors such as economic conditions, labor market structures, and educational system quality [18,19].

This entry contributes to the existing literature by providing a comprehensive examination of the relationship between educational attainment and employment outcomes, presenting the theories on the relationship between education and employment; this is the first study to attempt this endeavor. The entry also presents a conceptual framework of the relationship and discusses the factors which influence the education–employment nexus, which the existing literature has not comprehensively addressed. Moreover, our work presents data on their connections from European countries, and finally, it highlights the implications and the conclusions that are derived from our analysis. By doing so, this entry aims to contribute to the ongoing discourse on how education systems can be reformed to better equip individuals for meaningful and sustainable employment in an ever-changing global economy.

2. Conceptual Framework of the Education and Employment Nexus

The relationship between education and employment is inherently complex, shaped by the interaction of multiple theoretical and empirical factors. From a theoretical standpoint, human capital theory suggests that education enhances individual productivity and employability, while signaling theory posits that educational credentials serve as indicators of a candidate’s attributes to employers. Social capital theory further emphasizes the role of networks and relationships in facilitating job access. These perspectives, along with frameworks such as skills mismatch theory and social reproduction theory, underscore that education’s impact on employment extends beyond simple cause–effect dynamics. It is influenced by the alignment between educational outcomes and labor market demands, the quality and accessibility of education, and broader socioeconomic contexts. This complexity necessitates a comprehensive conceptual framework to understand the diverse pathways through which education affects labor market outcomes.

To better understand this multifaceted nexus, we developed a conceptual framework based on a twofold methodological approach. First, we conducted a thematic synthesis of key theoretical models, including human capital theory, signaling theory, social capital theory, skills mismatch theory, and others, as outlined in detail in Section 3. These theories were selected based on their prevalence in the literature and their relevance in explaining the education–employment relationship. Second, we integrated insights from a comparative review of empirical data from European countries (presented in Section 5), which provides real-world context to support and refine the conceptual assumptions. Together, this methodological process grounds the framework in both theoretical rigor and empirical relevance, offering a structured lens through which to analyze how educational attainment influences employment outcomes.

In what follows, we describe the conceptual framework of the relationship presenting the related avenues and the channels which highlight the role of various contextual factors in moderating this nexus.

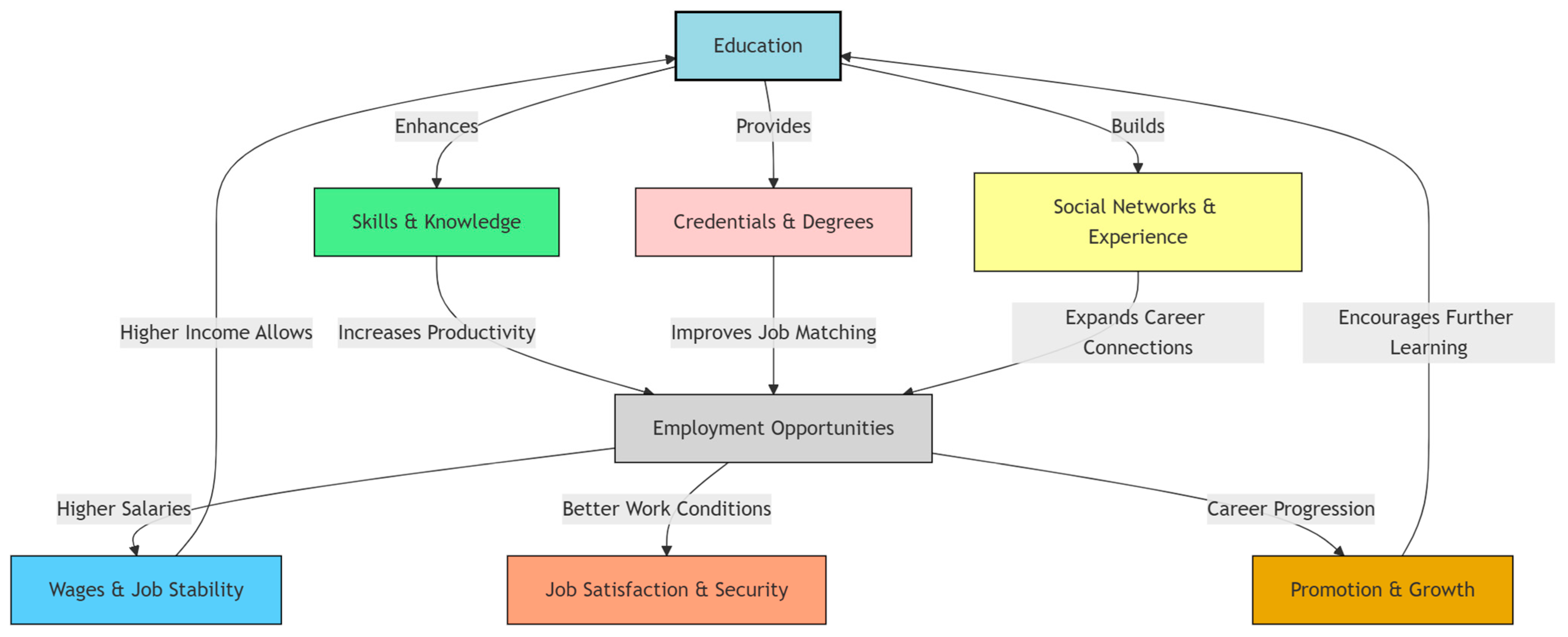

The conceptual framework (Figure 1) illustrates the relationship between education and employment and encompasses several interconnected components that collectively influence labor market outcomes. Firstly, education serves as the foundational element, impacting individuals through multiple pathways. More specifically, education enhances an individual’s skills and knowledge, increasing productivity and adaptability in various job roles (human capital theory). Moreover, educational credentials signal to employers a candidate’s competence and commitment, facilitating better job matching (signaling theory). In addition, educational institutions provide networks and experiences that can lead to expanded career connections and opportunities (social capital theory).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of the education and employment nexus.

Secondly, the framework reveals the culmination of the above factors, where enhanced human capital, effective signaling, and robust social networks lead to improved employment prospects and opportunities. At a third level, regarding the outcomes of employment, we identify three dimensions: (i) higher educational attainment often correlates with increased earnings and stable employment (wages and job stability); (ii) education can lead to positions with better working conditions and job security (job satisfaction and security); and (iii) educational qualifications can facilitate promotions and career advancement (career progression). In addition, there is also a feedback loop, since employment outcomes can influence further educational pursuits. For instance, higher wages may provide resources for additional education, and career progression can motivate continuous learning.

In general, this conceptual framework highlights the multifaceted role of education in shaping employment outcomes. These outcomes are influenced by a combination of individual capabilities, employer perceptions, and social networks. The framework offers a holistic understanding of the complex relationship between education and employment, and it serves as a guide for our analysis. Education provides a foundation for skill acquisition, job attainment, and economic mobility. However, structural factors, such as labor market conditions, credential requirements, and access to social networks, also play critical roles. By understanding these dynamics, policymakers, educators, and employers can design effective strategies to bridge the gap between education and employment. This ensures that learning systems adequately prepare individuals for sustainable and meaningful careers. In the next section, we present the theories on the relationship between education and employment.

3. Theories on the Relationship Between Education and Employment

The relationship between education and employment has been explored through various theoretical perspectives, which offer different explanations for the mechanisms underlying this connection. The theories which are most often found in the related literature are human capital theory, signaling theory, and social capital theory. However, there are several theoretical considerations which are also relevant in understanding this nexus. In this section, we provide an overview of the key theories that inform us of our understanding of the education–employment relationship.

3.1. Human Capital Theory

Human capital theory posits that investment in education and training enhances an individual’s productive capacity, thereby increasing their earning potential and employability [20,21]. Within this framework, the human capital theory emphasizes that individuals make rational decisions to invest in their education based on the expected returns, in terms of future earnings and career prospects [22]. This theory is the most widely accepted framework that explains the relationship between education and employment and suggests that individuals invest in education and training to acquire knowledge, skills, and competencies that enhance their productivity and earning potential in the labor market [23].

This theory also assumes that individuals make rational choices to invest in their education, based on the expected returns from this investment, such as higher wages and better job prospects [14,24]. The prestige of a credential may be as important as the knowledge gained in determining the value of an education. This points to the existence of market imperfections such as non-competing groups and labor market segmentation [21].

3.2. Signaling Theory

Signaling theory [25] offers an alternative perspective on the relationship between education and employment. This theory argues that education functions as a signal to employers, indicating a candidate’s abilities, work ethic, and adaptability. In other words, employers use educational credentials as a filtering mechanism in the hiring process, if higher levels of education correlate with superior job performance [26]. Signaling theory suggests that education serves as a signal to employers about an individual’s abilities and productivity, rather than directly enhancing their human capital [24].

According to this view, employers use educational attainment as a proxy for unobservable characteristics, such as intelligence, motivation, and discipline, which are valued in the labor market. The implication is that even if education does not directly improve an individual’s productivity, it can still lead to better employment outcomes by signaling desirable traits to potential employers. The signaling value of education may vary depending on the specific job or industry [25,27]. For instance, a college degree may be a positive signal for certain job opportunities but a negative signal for others.

3.3. Social Capital Theory

Social capital theory emphasizes the role of social networks and relationships in shaping the connection between education and employment [28,29]. This theory suggests that individuals with strong social networks and connections are more likely to have better employment outcomes, as they can leverage these connections to access job opportunities and resources.

According to this perspective, the value of an individual’s education is not solely determined by their academic credentials, but also by the social capital they have accumulated through their educational and professional experiences [30,31]. For example, attending an elite university may provide access to a powerful network of alumni and connections that can facilitate job search and career advancement, even if the education itself does not directly enhance human capital [32,33]. In general, social capital theory emphasizes that social connections and relationships play a crucial role in translating educational attainment into favorable employment outcomes.

In summary, these three key theories—human capital theory, signaling theory, and social capital theory—provide complementary perspectives on the complex relationship between education and employment. Empirical evidence suggests that all three mechanisms are at play, and that the relative importance of each varies depending on the specific context and labor market conditions.

3.4. Skills Mismatch Theory

Skills mismatch theory suggests that the relationship between education and employment is not always straightforward, as there can be a disconnect between the skills and competencies acquired through education and the skills demanded by the labor market [34,35]. This theory posits that a skills mismatch can occur when the skills and qualifications of individuals do not align with the needs of employers, leading to underemployment, job dissatisfaction, and suboptimal economic outcomes.

This theory argues that overeducation, where individuals have higher educational attainment than required for their job, can lead to underutilization of skills and potentially lower productivity. Conversely, undereducation, where individuals have lower educational attainment than required for their job, can result in skill gaps and reduced job performance [24,30]. The skills mismatch theory highlights the importance of aligning educational outcomes with labor market needs, as a mismatch between the two can have adverse consequences for both individuals and the economy [36].

3.5. Lifelong Learning Theory

Lifelong learning theory emphasizes the importance of continuous skill development and adaptation to changing labor market demands. This theory suggests that the relationship between education and employment is not static, but rather a dynamic process that requires individuals to engage in ongoing learning and skill acquisition throughout their careers [37]. As technological advancements and economic shifts rapidly transform the job market, the need for workers to continuously update their skills and knowledge becomes increasingly crucial [38].

According to this theory, the rapid pace of technological change and the evolving nature of work mean that individuals must continuously update their skills and knowledge to remain competitive in the labor market. This requires a shift in mindset from education as a one-time event to education as a lifelong process, where individuals are expected to engage in continuous learning and skill development to maintain their employability and adapt to changing job requirements [23].

Lifelong learning theory also highlights the importance of policies and programs that support and facilitate the development of skills and competencies over an individual’s lifetime, to ensure their employability and adaptability in the face of a constantly evolving labor market [39].

3.6. Social Reproduction Theory

Social reproduction theory suggests that the relationship between education and employment is shaped by broader societal structures and power dynamics. This theory argues that the education system serves to perpetuate existing social and economic inequalities, as it reflects the dominant cultural norms and values of the ruling class [40,41,42]. According to this perspective, the educational system is designed to reproduce the social and economic status quo, as it tends to favor and reward the cultural capital (e.g., language, behaviors, and knowledge) of the dominant social groups [24].

For instance, the theory suggests that individuals from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds may face additional barriers in accessing and succeeding within the education system, as their cultural and social capital may not align with the dominant norms and expectations of the educational institution [43,44]. As a result, the theory contends that the relationship between education and employment is not purely meritocratic, but rather shaped by underlying structures of power and inequality within society. Social reproduction theory highlights the need to address these systemic barriers and inequities within the education system to promote more equitable employment outcomes.

3.7. Career Development Theory

Career development theory emphasizes the importance of individual agency and self-management in the relationship between education and employment. According to this theory, individuals play an active role in shaping their career trajectories, and their educational and professional choices are not solely determined by external factors, such as labor market demands or institutional structures [45]. Super’s career development theory, for instance, proposes that career planning is a lifelong process, and that individuals navigate through different career stages, each with their own developmental tasks and challenges.

This theory suggests that individuals’ self-concept, values, interests, and skills play a crucial role in their career decision-making and the alignment between their educational pursuits and employment outcomes [46]. Through this lens, the relationship between education and employment is understood as a dynamic and interactive process, where individuals actively engage in self-exploration, goal setting, and skill development to enhance their employability and achieve their desired career outcomes.

3.8. Technological Change Theory

Technological change theory posits that the relationship between education and employment is heavily influenced by the pace and nature of technological advancements. According to this theory, technological innovations and the resulting shifts in the labor market can lead to changes in the skills and qualifications required for various occupations [47,48]. For instance, the rise of automation and artificial intelligence may render certain job tasks obsolete while creating new job opportunities that require different skill sets [49,50,51].

This theory suggests that as the nature of work evolves, individuals must continuously update their knowledge and skills to remain competitive in the labor market [50,52]. This may involve pursuing additional education or training to acquire the skills necessary to adapt to technological changes and secure employment in the evolving job market. Technological change theory highlights the importance of aligning educational programs and curriculum with the changing skill demands of the labor market, in order to ensure that graduates possess the knowledge and competencies required for success in their chosen careers.

Overall, the relationship between education and employment is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon, shaped by a variety of theoretical frameworks and perspectives. Understanding these different theories can provide valuable insights into the factors that influence the connection between educational attainment and labor market outcomes.

4. Factors Influencing the Education–Employment Relationship

The relationship between education and employment is shaped by a wide range of inter-related factors that operate at multiple levels. At the individual level, characteristics such as educational attainment, skill sets (e.g., cognitive, technical, and soft skills), motivation, and adaptability significantly influence employment outcomes. Institutional factors include the structure and quality of educational systems, the degree of alignment between curricula and labor market demands, and the availability of support services such as career guidance and vocational training. Broader societal dynamics encompass economic development levels, cultural norms regarding education and work, gender roles, and systemic inequalities linked to socioeconomic status, geography, or disability. These categories interact in complex ways to either facilitate or constrain individuals’ transition from education to employment, and are further elaborated through the theoretical frameworks and empirical data discussed in subsequent sections of the manuscript.

4.1. Individual Factors

Individual factors, such as an individual’s educational attainment, skills, and personal characteristics, can significantly impact their employment outcomes. For instance, research indicates that higher levels of educational attainment, such as tertiary education, are associated with increased probabilities of employment compared to individuals with lower levels of education [14]. This suggests that the acquisition of knowledge and skills through education can enhance an individual’s employability.

In addition, the specific skills and competencies developed through educational programs can be crucial in determining an individual’s ability to secure employment and perform effectively in their chosen occupation. These skills can include technical skills, critical thinking, problem-solving, communication, and teamwork, among others [53]. Furthermore, individual characteristics, such as motivation, self-efficacy, and adaptability, can also play a significant role in an individual’s ability to navigate the labor market and achieve their desired career outcomes [54].

4.2. Institutional Factors

Institutional factors, such as the structure and policies of the education system and the labor market, can also influence the relationship between education and employment. For instance, the degree of alignment between the educational curriculum and the skills demanded by employers can impact the labor market outcomes of graduates [4]. If the education system fails to adequately prepare students with the relevant skills and competencies, graduates may struggle to find employment or may be underemployed in roles that do not fully utilize their educational qualifications [55,56].

The availability and quality of career guidance and support services within educational institutions can also be a critical factor in shaping the transition from education to employment [57]. These services can help students navigate the labor market, identify career options, and develop strategies for securing employment. Additionally, the broader institutional context, such as the economic and political environment, can shape the demand for certain skills and qualifications in the labor market, thereby influencing the employment prospects of graduates.

4.3. Broader Societal Factors

Broader societal factors, such as demographic trends, cultural norms, and social inequalities, can also shape the relationship between education and employment [4]. For example, changes in the age distribution of the population, such as an aging workforce or a growing youth population, can impact the demand for certain skills and qualifications in the labor market [11].

Cultural and societal norms around the value of education, career paths, and gender roles can also influence individuals’ educational and career choices, as well as the perceptions and expectations of employers. Moreover, social inequalities, such as those based on race, socioeconomic status, or disability, can create barriers to educational and employment opportunities, leading to disparities in labor market outcomes [58]. These broader societal factors can intersect individual and institutional factors, creating a complex web of influences on the education–employment relationship.

4.4. Gender Norms

Research has shown that the relationship between education and employment can also be significantly influenced by gender norms and stereotypes [58]. In some contexts, higher levels of education among women may not translate into commensurate employment opportunities due to persistent gender biases and discrimination in the labor market [59].

Existing research has highlighted the barriers that women face in accessing and progressing in the labor market, such as the unequal distribution of domestic and caregiving responsibilities, workplace discrimination, and the under-representation of women in certain high-paying and high-status occupations [19]. Addressing these gender-based disparities in the education–employment relationship requires a multifaceted approach that challenges gender stereotypes, promotes equal opportunities, and fosters inclusive work environments.

4.5. Economic Development

The extent to which education translates into employment opportunities can also be influenced by the level of economic development [60,61]. In developed economies, higher levels of educational attainment are more strongly associated with better employment outcomes, as the labor market can absorb highly skilled workers more effectively [62].

In contrast, in developing economies, the labor market may not be able to provide sufficient high-quality employment opportunities for the growing number of educated individuals, leading to skills mismatch and underemployment [19]. Ensuring that the education system and the labor market are well-aligned and responsive to the evolving economic context is crucial for maximizing the benefits of education for individuals and the broader society.

4.6. Field of Study

The field of study pursued in higher education can also play a significant role in shaping employment outcomes [63]. Some fields, such as engineering, medicine, and certain sciences, may be more closely aligned with specific occupations and in high demand in the labor market, leading to better employment prospects for graduates.

In contrast, graduates from fields such as the humanities or social sciences may face more challenges in finding relevant employment, unless they possess transferable skills that are valued by employers across different sectors [64]. Addressing this mismatch between educational choices and labor market demands requires a more nuanced understanding of the skills and competencies developed through different fields of study and a stronger collaboration between educational institutions and employers.

4.7. Availability and Accessibility of Educational Opportunities

The availability and accessibility of educational opportunities can also influence the relationship between education and employment. In some contexts, access to higher education may be limited or unequal, with certain socioeconomic groups facing barriers to obtaining the necessary qualifications. Such disparities in educational access can lead to inequalities in employment outcomes, as individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds may have fewer opportunities to develop the skills and credentials demanded by the labor market. For instance, factors such as socioeconomic status and geographic location can all affect an individual’s access to education and, consequently, their employment outcomes.

Addressing these complex factors that shape the education–employment relationship requires a multifaceted approach involving policymakers, educational institutions, employers, and broader societal stakeholders. Efforts to enhance the alignment between the education system and the labor market, promote inclusive access to quality education, and address underlying social inequalities can all contribute to strengthening the positive linkages between education and employment outcomes [4,64,65].

In conclusion, the relationship between education and employment is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon, influenced by a range of individual, contextual, and institutional factors. Policymakers, educators, and employers must work together to address these various factors and enhance the employability of individuals, ultimately contributing to the economic and social well-being of societies [14,53,56,66].

5. Evidence from European Countries

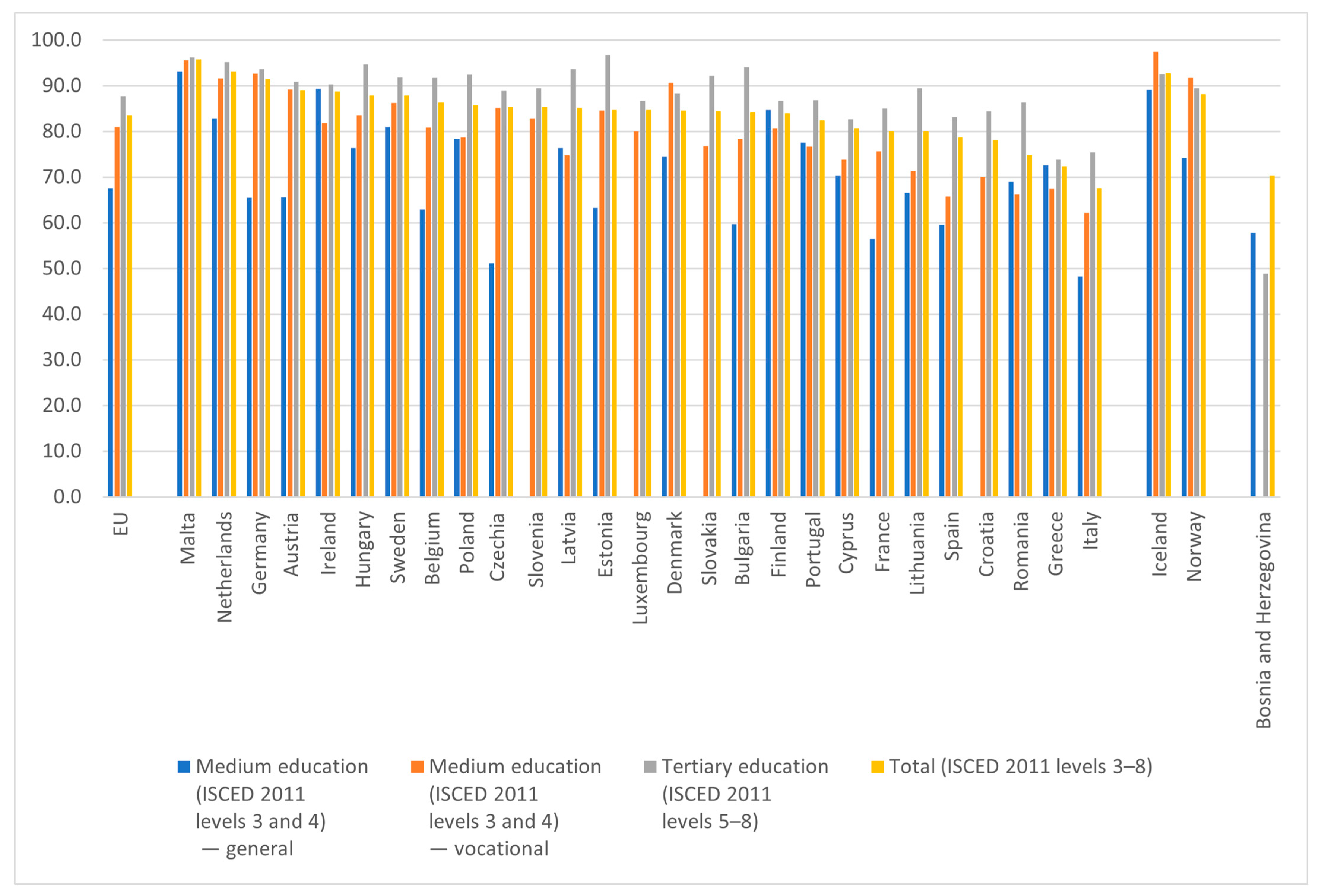

The existing evidence on the relationship between education and employment outcomes in European countries provides valuable insights into the nuances and complexities of this relationship. In this section, we use data from Eurostat [67] (online data code: edat_lfse_24), which can be found in Table A1, Appendix A, to investigate the relationship between the employment rates for recent graduates and level of educational attainment within the European Union. The level of educational attainment is categorized into the following main groups: (a) medium education (ISCED 2011 levels 3 and 4—general track), (b) medium education (ISCED 2011 levels 3 and 4—vocational track), (c) tertiary education (ISCED 2011 levels 5–8), and d) total percentage of people attaining at least medium education (ISCED 2011 levels 3–8).

Figure 2 above shows that, in 2023, those with tertiary education had the highest employment rates, while people with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education (i.e., a medium level of education) had the lowest employment rates. There are also several other outcomes from the data analysis. Regarding the general medium education (ISCED levels 3–4), we observe that Malta (93.2%), Ireland (89.3%), and Iceland (89.1%) are the countries with the highest general education participation, whereas Italy (48.3%), Czechia (51.1%), and France (56.5%) are the countries with the lowest general education participation. With respect to vocational medium education (ISCED levels 3–4), the countries with the highest participation in vocational education are Iceland (97.4%), Malta (95.6%), and Germany (92.7%), while the countries with the lowest vocational education participation are Italy (62.2%), Greece (67.4%), and Romania (66.2%). As for tertiary education (ISCED levels 5–8), the countries with the highest tertiary education attainment are Estonia (96.7%), Malta (96.2%), and Netherlands (95.2%), and the countries with the lowest tertiary education attainment are Bosnia and Herzegovina (48.9%), Greece (73.9%), Italy (75.4%), and Spain (83.1%). According to [67], Spain, Greece, and Italy are the European countries with the highest unemployment rates. Combining the fact that Southern European countries lag in tertiary education, we could suggest that lower higher education is connected with lower employment levels.

Figure 2.

Employment rates of recent graduates (aged 20–34), by level of educational attainment, 2023. Data from [67].

Based on the data, we can also analyze how different levels of education impact employability in European countries. First, there is a strong correlation between educational attainment and employment rates across European countries, since countries with higher overall education attainment (ISCED 3–8), such as Malta (95.8%), Netherlands (93.2%), and Germany (91.5%), tend to have higher employment rates. Moreover, countries with lower educational attainment, such as Italy (67.5%) and Bosnia and Herzegovina (70.3%), often experience higher unemployment rates and more economic challenges. Therefore, higher education leads to better job opportunities. For instance, countries with high tertiary education rates (e.g., Estonia, 96.7%; Malta, 96.2%) typically have stronger knowledge-based economies (e.g., tech, finance, and research sectors). A well-educated workforce attracts investment, leading to better job creation. In addition, vocational education supports employment stability, as countries with strong vocational education systems (e.g., Germany, 92.7%; Austria, 89.2%) produce highly skilled workers in fields like engineering, healthcare, and trades, and these workers integrate into the job market faster than those with general education.

In sum, the data suggests that increased educational attainment, especially at the tertiary level, is associated with better employment prospects and outcomes in the European context. In addition, Northern and Western European countries generally have higher tertiary education rates and vocational education systems that contribute to high overall attainment. Moreover, Southern and Eastern European countries struggle with lower general education participation and overall attainment, with countries like Italy, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Greece falling behind. Furthermore, vocational education is strong in Germany, Austria, and Iceland, supporting industry-focused employment paths. Finally, with respect to tertiary education, some countries still lag significantly (e.g., Bosnia and Herzegovina).

5.1. Key Findings from EU Data

The evidence discussed reveals important insights into the relationship between education and employment outcomes, with several key takeaways for policymakers and stakeholders: First, higher levels of educational attainment, particularly at the tertiary level, are associated with better employment prospects and outcomes across European countries. Countries with stronger tertiary education systems and higher tertiary education enrollment rates tend to have lower unemployment rates and more robust knowledge-based economies. Second, vocational education and training also play a crucial role in enhancing employability and supporting industry-specific skills development. Countries with strong dual vocational education systems, such as Germany and Austria, can produce highly skilled workers who integrate into the labor market more effectively. Third, there are significant disparities in educational attainment and employment outcomes between different European regions and countries. Southern and Eastern European countries generally lag in terms of overall educational attainment, and this is reflected in their higher unemployment rates compared to their Northern and Western European counterparts.

The analysis reveals a complex and multifaceted relationship, influenced by individual, contextual, and institutional factors. Higher levels of educational attainment, especially tertiary education, are generally associated with improved employment prospects and outcomes. However, the strength of this relationship varies across countries, highlighting the importance of considering national contexts and policy frameworks. Vocational education and training also play a vital role in enhancing employability, providing industry-specific skills that facilitate labor market integration. This is particularly evident in countries like Germany and Austria, which have strong dual vocational education systems.

Moreover, disparities in educational attainment and employment outcomes exist between different European regions and countries. Southern and Eastern European countries often lag behind their Northern and Western counterparts in terms of overall educational attainment, contributing to higher unemployment rates in these regions. Furthermore, the prevalence of low-skilled, precarious jobs in certain sectors, including tourism, poses a challenge to both individuals and the overall economy. Addressing these challenges requires a multi-pronged approach involving policymakers, educators, and employers.

5.2. Policy Implications

Several policy implications emerge from this analysis. Policymakers should prioritize investments in education and training programs that align with labor market needs, promoting both general and vocational skills development. This includes strengthening tertiary education systems, expanding access to vocational training opportunities, and fostering closer collaboration between educational institutions and employers. Furthermore, policies aimed at improving the quality of jobs and reducing precariousness in the labor market are essential for attracting and retaining skilled workers. These policies should consider regional disparities and target interventions to address specific challenges faced by different countries and communities. By working together, policymakers, educators, and employers can enhance the employability of individuals, ultimately contributing to economic and social well-being across Europe.

6. Conclusions

The relationship between education and employment is a complex and multifaceted one, with significant implications for individuals, economies, and societies. This nexus has been explored through various theoretical perspectives, which offer different explanations for the mechanisms underlying this connection, but the theories which are most often found in the related literature are human capital theory, the signaling theory, and the social capital theory. In our analysis, we developed a conceptual framework of their relationship which also highlights the above-mentioned multifaceted nature of this relationship. Within this framework, their relationship is influenced by a range of factors, including individual characteristics, institutional structures, and broader societal dynamics.

We also used data for European countries, which demonstrated the importance of higher levels of educational attainment, particularly at the tertiary level, in supporting positive employment outcomes, as well as the crucial role of vocational education and training programs. Countries such as Germany and Austria, which have well-established dual vocational training systems, consistently report high employment rates among recent graduates. These systems successfully integrate practical workplace training with classroom instruction, facilitating smoother transitions into the labor market. Similarly, countries like Estonia and Malta, with high rates of tertiary education attainment, show strong performance in knowledge-based economic sectors.

In contrast, countries in Southern and Eastern Europe, including Italy, Greece, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, tend to lag behind in both tertiary and vocational education participation. These nations also report comparatively lower employment rates, suggesting a direct link between shortcomings of the educational system and challenges in the labor market.

The analysis also revealed significant disparities in educational attainment and employment outcomes between different European regions and countries, with Southern and Eastern European countries generally lagging behind their Northern and Western counterparts. Addressing these challenges requires a comprehensive approach involving policymakers, educators, and employers.

Policymakers should prioritize investments in education and training programs that align with labor market needs, promote both general and vocational skills development, and foster closer collaboration between educational institutions and employers. Policies aimed at improving the quality of jobs and reducing precariousness in the labor market are also essential for attracting and retaining skilled workers. By working together to address these challenges, stakeholders can enhance the employability of individuals, ultimately contributing to economic and social well-being across Europe.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.G. and K.G.; methodology, G.G.; validation, T.G. and K.G.; formal analysis, G.G.; investigation, G.G.; data curation, G.G.; Writing—original draft preparation, G.G.; Writing-review and editing, G.G., T.G. and K.G.; visualization, T.G. and K.G.; supervision, T.G.; project administration, G.G.; funding acquisition, G.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Employment rates of recent graduates (aged 20−34) not in education and training, by level of educational attainment, 2023 (1). Data from [67].

Table A1.

Employment rates of recent graduates (aged 20−34) not in education and training, by level of educational attainment, 2023 (1). Data from [67].

| Medium Education (ISCED 2011 Levels 3 and 4) General | Medium Education (ISCED 2011 Levels 3 and 4) Vocational | Tertiary Education (ISCED 2011 Levels 5–8) | Total (ISCED 2011 Levels 3–8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EU | 67.6 | 81.0 | 87.7 | 83.5 |

| Malta (2)(3) | 93.2 | 95.6 | 96.2 | 95.8 |

| Netherlands | 82.8 | 91.6 | 95.2 | 93.2 |

| Germany | 65.5 | 92.7 | 93.6 | 91.5 |

| Austria (2) | 65.6 | 89.2 | 90.9 | 89.0 |

| Ireland | 89.3 | 81.8 | 90.3 | 88.7 |

| Hungary | 76.3 | 83.5 | 94.7 | 87.9 |

| Sweden | 81.0 | 86.2 | 91.8 | 87.9 |

| Belgium | 62.9 | 80.9 | 91.7 | 86.4 |

| Poland | 78.4 | 78.7 | 92.4 | 85.8 |

| Czechia (2) | 51.1 | 85.2 | 88.8 | 85.4 |

| Slovenia | - | 82.8 | 89.5 | 85.4 |

| Latvia (2)(3) | 76.4 | 74.8 | 93.6 | 85.2 |

| Estonia | 63.3 | 84.6 | 96.7 | 84.7 |

| Luxembourg | - | 80.0 | 86.7 | 84.7 |

| Denmark | 74.5 | 90.6 | 88.3 | 84.6 |

| Slovakia | - | 76.8 | 92.2 | 84.5 |

| Bulgaria (2) | 59.7 | 78.4 | 94.1 | 84.2 |

| Finland | 84.7 | 80.6 | 86.7 | 84.0 |

| Portugal | 77.5 | 76.7 | 86.8 | 82.4 |

| Cyprus (3) | 70.3 | 73.9 | 82.7 | 80.6 |

| France | 56.5 | 75.6 | 85.0 | 80.1 |

| Lithuania | 66.6 | 71.3 | 89.5 | 80.0 |

| Spain | 59.6 | 65.8 | 83.1 | 78.7 |

| Croatia | - | 70.0 | 84.4 | 78.2 |

| Romania | 69.0 | 66.2 | 86.3 | 74.8 |

| Greece | 72.7 | 67.4 | 73.9 | 72.3 |

| Italy | 48.3 | 62.2 | 75.4 | 67.5 |

| Iceland | 89.1 | 97.4 | 92.5 | 92.8 |

| Norway | 74.2 | 91.7 | 89.4 | 88.2 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 57.8 | - | 48.9 | 70.3 |

(1) Graduates: having graduated within previous 1 to 3 years. Medium: Upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education. (2) Medium education (ISCED 2011 levels 3 and 4)—general: low reliability. (3) Medium education (ISCED 2011 levels 3 and 4)—vocational: low reliability.

References

- Archer, M. Social Origins of Educational Systems; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, K. School Leavers and Their Prospects; OUP: Oxford, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Green, A. Education and State Formation; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bisht, N.; Pattanaik, F. Exploring the Magnitude of Inclusion of Indian Youth in the World of Work Based on Choices of Educational Attainment. J. Econ. Dev. 2021, 23, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- deBruin, A.; Dupuis, A. Making Employability ‘Work’. J. Interdiscip. Econ. 2008, 19, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, J. The Economics of Education, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psacharopoulos, G. Education and Development. World Bank Res. Obs. 1988, 3, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psacharopoulos, G.; Patrinos, H.A. Returns to Investment in Education: A Decennial Review of the Global Literature. Educ. Econ. 2018, 26, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woessmann, L. The Economic Case for Education. Educ. Econ. 2015, 24, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbison, F.H.; Myers, C.A. Education and Employment in the Newly Developing Economies. Comp. Educ. Rev. 1964, 8, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinchliffe, K. Education and the labour marker. In Economics of Education: Research and Studies; Psacharopoulos, G., Ed.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; pp. 315–323. [Google Scholar]

- Kokkinopoulou, E.; Vrontis, D.; Thrassou, A. The Impact of Education on Productivity and Externalities of Economic Development and Social Welfare: A Systematic Literature Review. Cent. Eur. Manag. J. 2025; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Education at a Glance 2024: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budría, S.; Telhado-Pereira, P. The Contribution of Vocational Training to Employment, Job-related Skills and Productivity: Evidence from Madeira. Int. J. Train. Dev. 2009, 13, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajacova, A.; Lawrence, E. The Relationship Between Education and Health: Reducing Disparities Through a Contextual Approach. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2018, 39, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, B.C. IIEP Research on Higher Education and Employment: A Response. Comp. Educ. Rev. 1982, 26, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Li, X.; Sun, S.; Law, R.; Qi, X.; Dong, Y. Influencing Factors of Students’ Learning Gains in Tourism Education: An Empirical Study on 28 Tourism Colleges in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, B. The Impact of Higher Education on High Quality Economic Development in China: A Digital Perspective. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Cao, S. What Factors are Driving the Rapid Growth of Education Levels in China? Heliyon 2023, 9, e16342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education; SSRN Electronic Journal, RELX Group: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1964; Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1496221 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Becker, G.S. Human Capital; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1983; Available online: https://openlibrary.org/books/OL5073284M/Human_capital (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Tannen, M.B. The Distribution of Family Incomes: A Reexamination. South. Econ. J. 1976, 42, 666–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, C. Education, Skill Training, and Lifelong Learning in the Era of Technological Revolution. Asian-Pac. Econ. Lit. 2020, 34, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchante, A.J.; Ortega, B.; Pagán, R. An Analysis of Educational Mismatch and Labor Mobility in the Hospitality Industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2007, 31, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. Job Market Signaling. Q. J. Econ. 1973, 87, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altonji, J.G.; Pierret, C.R. Employer Learning and the Signaling Value of Education. Q. J. Econ. 1996, 116, 313–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosti, L.; Yamaguchi, C.; Castagnetti, C. Educational Performance as Signaling Device: Evidence from Italy. Econ. Bull. 2005, 9, 1–11. Available online: http://www.accessecon.com/pubs/EB/2005/Volume9/EB-05I20006A.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Coleman, J.S. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The Forms of Capital. In Handbook for Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J.G., Ed.; Greenwood Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autentico, J.M.; Alerta, G. Incidence of Job Mismatch Among TVL Graduates in Butuan City, Philippines. PEOPLE Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 6, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, R. Functional and Conflict Theories of Educational Stratification. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1971, 36, 1002–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, N.D. Social Capital, Academic Achievement, and Postgraduation Plans at an Elite, Private University. Sociol. Perspect. 2009, 52, 185–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, L.A. Pedigree: How Elite Students Get Elite Jobs, 2nd ed.; Economics Books, Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2016; p. 10723. [Google Scholar]

- Badillo-Amador, L.; Vila, L.E. Education and Skill Mismatches: Wage and Job Satisfaction Consequences. Int. J. Manpow. 2013, 34, 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgado, A.J.; Sequeira, T.N.; Santos, M.; Ferreira-Lopes, A.; Reis, A.B. Measuring Labour Mismatch in Europe. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 129, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, H.; Maurer, J.; Hawley, J.D. The Role of Education, Occupational Match on Job Satisfaction in the Behavioral and Social Science Workforce. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2019, 30, 407–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuijnman, A. Measuring Lifelong Learning for the New Economy. Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2003, 33, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ra, S.; Shrestha, U.; Khatiwada, S.; Yoon, S.W.; Kwon, K. The Rise of Technology and Impact on Skills. Int. J. Train. Res. 2019, 17 (Suppl. S1), 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laal, M. Benefits of Lifelong Learning. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 4268–4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Cultural Reproduction and Social Reproduction. In Knowledge, Education, and Cultural Change; Brown, R., Ed.; Tavistock Publications: London, UK, 1973; pp. 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, P. Middle-Class Social Reproduction: The Activation and Negotiation of Structural Advantages. Sociol. Forum 2005, 20, 245–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Social Reproduction in K-12: Life-long Effects on Middle-class Students. In Proceedings of the 2021 4th International Conference on Humanities Education and Social Sciences (ICHESS 2021), Xishuangbanna, China, 29–31 October 2021; pp. 2566–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.; Hu, W.; Griffin, B. Cultures of Success: How Elite Students Develop and Realise Aspirations to Study Medicine. Aust. Educ. Res. 2022, 50, 1127–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monkman, K.; Ronald, M.; Théramène, F.D. Social and Cultural Capital in an Urban Latino School Community. Urban Educ. 2005, 40, 4–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Lent, R.; Lent, R.W. Career Development and Counseling: A Social Cognitive Framework. In Career Development and Counseling; Brown, S., Lent, R., Eds.; WILEY: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.D.; Blustein, D.L. Readiness for Career Choices: Planning, Exploring, and Deciding. Career Dev. Q. 1994, 43, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoğlu, D.; Autor, D. Skills, Tasks and Technologies: Implications for Employment and Earnings. In Handbook of Labour Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 4, Part B; pp. 1043–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, M.; Chen, N. How Artificial Intelligence Affects the Labour Force Employment Structure from the Perspective of Industrial Structure Optimisation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, J.; Seamans, R. AI and the Economy. Innov. Policy Econ. 2018, 19, 161–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, D. Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Employment and Workforce Development: Risks, Opportunities, and Socioeconomic Implications. Oppor. Socioecon. Implic. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, J. Digital Technologies and the Future of Employment. SSRN Electron. J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, M.R.; Autor, D.; Bessen, J.; Brynjolfsson, E.; Cebrián, M.; Deming, D.; Feldman, M.P.; Groh, M.; Lobo, J.; Moro, E.; et al. Toward Understanding the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Labor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 6531–6539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tushar, H.; Sooraksa, N. Global Employability Skills in the 21st Century Workplace: A Semi-systematic Literature Review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sun, Z. Study on the Definition of College Students’ Employability. ITM Web Conf. 2019, 25, 4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornali, F. Training and Developing Soft Skills in Higher Education. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Higher Education Advances (HEAd’18), Valencia, Spain, 20–22 June 2018; Universitat Politecnica de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M. Employability in Higher Education: Problems and Prospectives. South Asian Res. J. Bus. Manag. 2019, 1, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D. Navigating the Rapids: The Role of Educational and Careers Information and Guidance in Transitions between Education and Work. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 1999, 51, 371–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussemakers, C.; Oosterhout Kvan Kraaykamp, G.; Spierings, N. Women’s Worldwide Education–employment Connection: A Multilevel Analysis of the Moderating Impact of Economic, Political, and Cultural Contexts. World Dev. 2017, 99, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flabbi, L. Gender Differences in Education, Career Choices and Labor Market Outcomes on A Sample of OECD Countries; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/10986/9113/1/WDR2012-0023.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Antai, A.; Anam, B. Gender Disparity in Education, Employment and Access to Productive Resources as Deterrent to Economic Development. J. Public Adm. Gov. 2016, 6, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, P.; Wang, P.; Wang, Y.-C.; Yip, C.K. Educational Choice, Rural–urban Migration and Economic Development. Econ. Theory 2021, 74, 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neamţu, D.-M. Education, the Economic Development Pillar. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 180, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Klager, C.; Schneider, B. The Effects of Alignment of Educational Expectations and Occupational Aspirations on Labor Market Outcomes: Evidence from NLSY79. J. High. Educ. 2019, 90, 992–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okolie, U.C.; Nwosu, H.E.; Mlanga, S. Graduate Employability: How the Higher Education Institutions can Meet the Demand of the Labour Market. High. Educ. Ski. Work.-Based Learn. 2019, 9, 620–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, W. Education and Youth Integration into European Labour Markets. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 2005, 46, 461–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mileva, S. Skills and Competences as Main Concern for Innovation Capabilities between Universities and Tourism Industry. Tour. Dimens. 2015, 2, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Employment Rates of Young People Not in Education and Training by Sex, Educational Attainment Level and Years Since Completion of Highest Level of Education [edat_lfse_24__custom_2700333]. 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/bookmark/7757f3ff-aca0-460b-bd04-142cee177bbd?lang=en (accessed on 15 March 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).