Fostering Organizational Sustainability Through Employee Collaboration: An Integrative Approach to Environmental, Social, and Economic Dimensions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Results

- Common Purpose: A shared goal is essential for attracting and retaining members in the group, as it provides a sense of purpose.

- Reciprocity: The benefit gained by members, whether for themselves or others, particularly in the exchange of knowledge, makes collaboration valuable to participants.

- Enabling Environment: A supportive environment, often influenced by leadership and management style, facilitates goal achievement and creates a positive atmosphere where members feel comfortable communicating.

- Trust: Trust is one of the most frequently cited factors when it comes to fostering collaboration. It enhances openness and creates confidence that other members will fulfill tasks and agreements honestly.

- Personal Traits: Individual characteristics can either encourage or hinder collaboration. Members may have diverse personalities, but key traits such as openness to communication, teamwork, and the ability to understand others’ perspectives, values, and cultural norms are vital for strengthening relationships within the group. It is important that members feel understood, accepted, and open within the team.

4. Conclusions and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Lange, D.E.; Busch, T.; Delgado-Ceballos, J. Sustaining Sustainability in Organizations. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.; Lopes, J.M.; Travassos, M.; Paiva, M.; Cardoso, I.; Peixoto, B.; Duarte, C. Strategic Organizational Sustainability in the Age of Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słupska, U.; Drewniak, Z.; Drewniak, R.; Karaszewski, R. Building Relations between the Company and Employees: The Moderating Role of Leadership. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moles, R.; Foley, W.; Morrissey, J.; Regan, B.O. Practical appraisal of sustainable development—Methodologies for sustainability measurement at settlement level. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2008, 28, 144–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.; Bossink, B.; van Vliet, M. Dynamic capabilities and organizational routines for managing innovation towards sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajikawa, Y.; Tacoa, F.; Yamaguchi, K. Sustainability science: The changing landscape of sustainability. Sustain. Sci. 2014, 9, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, R.; Maher, M.; McAlpine, C.A.; Mann, S.; Seabrook, L. Overcoming barriers to sustainability by combining conceptual, visual, and networking systems. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1357–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bah, M.O.P.; Sun, Z.; Hange, U.; Edjoukou, A.J.R. Effectiveness of Organizational Change through Employee Involvement: Evidence from Telecommunications and Refinery Companies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, V.K.; Vu, T.N.Q.; Phan, T.T.; Nguyen, N.A. The Impact of Organizational Culture on Employee Performance: A Case Study at Foreign-Invested Logistics Service Enterprises Approaching Sustainability Development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Stefano, F.; Bagdadli, S.; Camuffo, A. The HR role in corporate social responsibility and sustainability: A boundary-shifting literature review. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, S.; Fernández-Salinero, S.; Topa, G. Sustainability in organizations: Perceptions of corporate social responsibility and spanish employees’ attitudes and behaviors. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Eli, M.U. Sustainability: Definition and five core principles, a systems perspective. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, S.C. Sustainability: A 21st century concept? Trends Plant Sci. 2022, 27, 619–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.; Ahmad, S.F.; Irshad, M.; Alsanie, G.; Khan, Y.; Ahmad, A.Y.A.B.; Aleemi, A.R. Impact of Green Process Innovation and Productivity on Sustainability: The Moderating Role of Environmental Awareness. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizenberg, E.; Jabareen, Y. Social Sustainability: A New Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E. From Neglect to Progress: Assessing Social Sustainability and Decent Work in the Tourism Sector. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, A.; Ullah, Z.; AlDhaen, F.S.; AlDhaen, E.; Yakymchuk, A. Enhancing Organizational Social Sustainability: Exploring the Effect of Sustainable Leadership and the Moderating Role of Micro-Level CSR. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsawy, M.; Marwan, Y. Economic Sustainability: Meeting Needs without Compromising Future Generations. Int. J. Econ. Financ. 2023, 10, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coletti, M.; Landoni, P. Collaborations for innovation: A meta-study of relevant typologies, governance and policies. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2018, 27, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soosay, C.A.; Hyland, P. A decade of supply chain collaboration and directions for future research. Supply Chain Manag. 2015, 20, 613–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fobbe, L. Analysing Organisational Collaboration Practices for Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beretta, E.; Burkhalter, C.; Camenisch, P.; Carcano-Monti, C.; Citraro, M.; Manini-Mondia, M.; Traversa, F. Organiblò: Engaging People in “Circular” Organizations and Enabling Social Sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F. Causes of Failure of Open Innovation Practices in Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezquerra-Lázaro, I.; Gómez-Pérez, A.; Mataix, C.; Soberón, M.; Moreno-Serna, J.; Sánchez-Chaparro, T. A Dialogical Approach to Readiness for Change towards Sustainability in Higher Education Institutions: The Case of the SDGs Seminars at the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, C.K.M. Collaboration modes, preconditions, and contingencies in organizational alliance: A comparative assessment. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4737–4743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

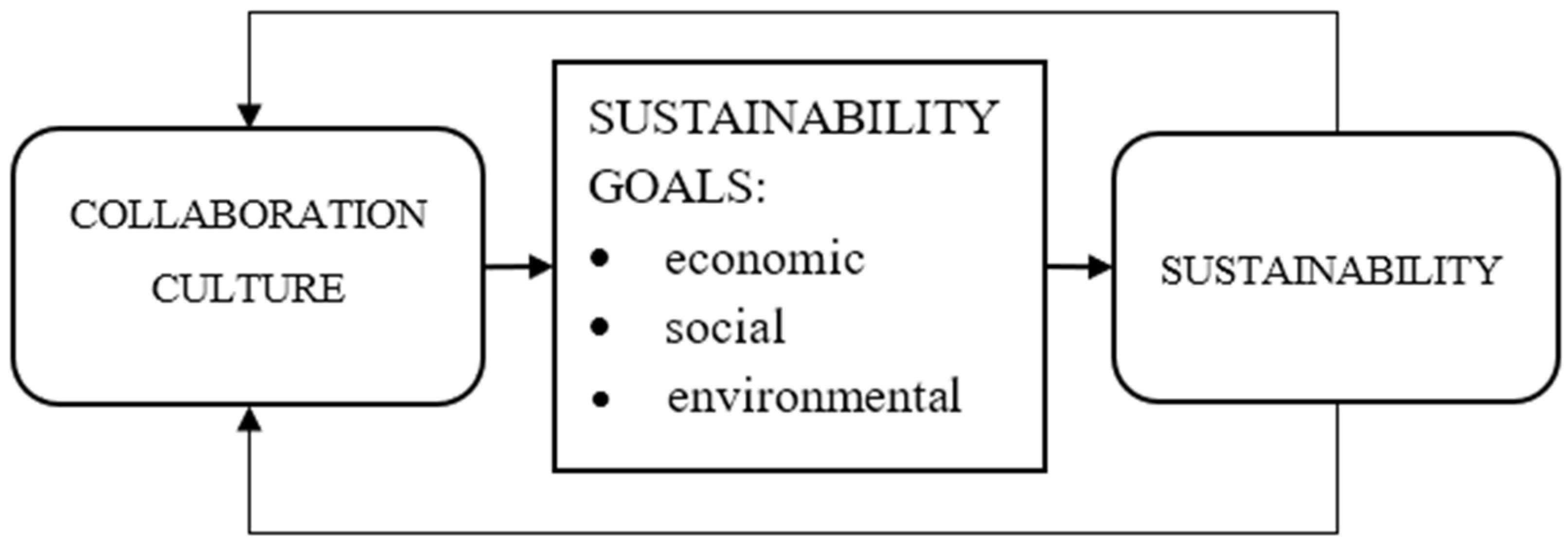

- Kumar, G.; Meena, P.; Difrancesco, R.M. How do collaborative culture and capability improve sustainability? J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 291, 125824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, P.; Chapman, R. From Continuous Improvement to Organizational Learning: Developmental Theory. Learn. Organ. 2003, 10, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namada, J. Organizational Learning and Competitive Advantage. Researchgates 2018, 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chughtai, M.S.; Syed, F.; Naseer, S.; Chinchilla, N. Role of adaptive leadership in learning organizations to boost organizational innovations with change self-efficacy. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 43, 27262–27281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Medne, A.; Lapiņa, I. Sustainability and Continuous Improvement of Organization: Review of Process-Oriented Performance Indicators. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2019, 5, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgrzywa-Ziemak, A.; Walecka-Jankowska, K. The relationship between organizational learning and sustainable performance: An empirical examination. J. Workplace Learn. 2021, 33, 155–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, F.; Lispi, L.; Staudacher, A.P.; Rossini, M.; Kundu, K.; Cifone, F.D. How to foster Sustainable Continuous Improvement: A cause-effect relations map of Lean soft practices. Oper. Res. Perspect. 2019, 6, 100091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haradhan, M. Knowledge Sharing among Employees in Organizations. J. Econ. Dev. Environ. People 2019, 8, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilderback, S. Integrating training for organizational sustainability: The application of Sustainable Development Goals globally. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2023, 48, 730–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoopetch, C.; Nimsai, S.; Kongarchapatara, B. The Effects of Employee Learning, Knowledge, Benefits, and Satisfaction on Employee Performance and Career Growth in the Hospitality Industry. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Zha, W.; Zhou, Q. The Impact of Enterprise Digital Capability on Employee Sustainable Performance: From the Perspective of Employee Learning. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decius, J.; Knappstein, M.; Klug, K. Which way of learning benefits your career? The role of different forms of work-related learning for different types of perceived employability. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2023, 33, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiri, R.; El-Metwally, A.; Sallinen, M.; Pöyry, M.; Härmä, M.; Toppinen-Tanner, S. The Role of Continuing Professional Training or Development in Maintaining Current Employment: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bramwell, O.; Ng, E. Toward a Collaborative, Transformative Model of Non-Profit Leadership. Adm. Sci. 2014, 4, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Ahmadi Malek, F.; Yaghoubi Farani, A.; Liobikienė, G. The Role of Transformational Leadership in Developing Innovative Work Behaviors: The Mediating Role of Employees’ Psychological Capital. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, A. Linking transformational leadership, creativity, innovation, and innovation-supportive climate. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 2277–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwaa, A.; Gyensare, M.A.; Susomrith, P. Transformational leadership with innovative behaviour: Examining multiple mediating paths with PLS-SEM. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2019, 40, 402–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafizur, R.; Abd Wahab, S.; Abdul Latiff, A. The Underlying Theories of Organizational Sustainability: The Motivation Perspective. J. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2023, 5, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketprapakorn, N.; Kantabutra, S. Toward an organizational theory of sustainability culture. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 32, 638–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulistiawan, J.; Moslehpour, M.; Diana, F.; Lin, P. Why and When Do Employees Hide Their Knowledge? Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, E.; Joseph, J. A Review on the Impact of Workplace Culture on Employee Mental Health and Well-Being. Int. J. Case Stud. Bus. IT Educ. 2023, 7, 291–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, C. Fostering a Positive Workplace Culture: Impacts on Performance and Agility. Researchgates 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakulin, S.L.; Pakulina, A.A. Sustainable development management of a modern enterprise. Trajectory Sci. 2016, 3. Available online: http://pathofscience.org/index.php/ps/article/view/50 (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Samaibekova, Z.; Choyubekova, G.; Isabaeva, K.; Samaibekova, A. Corporate sustainability and social responsibility. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 250, 06003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, I. Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Sustainability: Separate Pasts, Common Futures. Organ. Environ. 2008, 21, 245–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Shin, D. Modelling Community Resources and Communications Mapping for Strategic Inter-Organizational Problem Solving and Civic Engagement. J. Urban Technol. 2016, 23, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondirad, A.; Tolkach, D.; King, B. Stakeholder collaboration as a major factor for sustainable ecotourism development in developing countries. Tour. Manag. 2019, 78, 104024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ababneh, O. The impact of organizational culture archetypes on quality performance and total quality management: The role of employee engagement and individual values. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2020; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, K.S. Strategies and Benefits of Fostering Intra-Organizational Collaboration. In College of Professional Studies Professional Projects; Marquette University: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2010; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Sarong, J. Fostering Collaboration and Team Effectiveness in Educational Leadership: Strategies for Building High-Performing Teams and Networks. Randwick Int. Educ. Linguist. Sci. J. 2024, 5, 727–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulussen, S.; Geens, D.; Vandenbrande, K. Fostering a culture of collaboration: Organizational challenges of newsroom innovation. Researchgates 2011, 2, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Klassen, A.C.; Plano Clark, V.L.; Smith, K.C. Best Practices for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences; National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2011. Available online: http://obssr.od.nih.gov/mixed_methods_research (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: New York, HY, USA, 2011; ISBN 0-7619-1544-3. Available online: https://www.daneshnamehicsa.ir/userfiles/files/1/9-%20Content%20Analysis_%20An%20Introduction%20to%20Its%20Methodology.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Cole, M. Benchmarking: A Process for Learning or Simply Raising the Bar? Eval. J. Australas. 2009, 9, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Universal Lithuanian Encyclopedia. 2023. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Visuotin%C4%97_lietuvi%C5%B3_enciklopedija (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Kokubun, K.; Ino, Y.; Ishimura, K. Social capital and resilience make an employee cooperate for coronavirus measures and lower his/her turnover intention. arXiv 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; González-López, R.; Buenadicha-Mateos, M.; Tato-Jiménez, J.L. Work-Life Balance in Great Companies and Pending Issues for Engaging New Generations at Work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 5122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiroko, E. The Role of Servant Leadership and Resilience in Predicting Work Engagement. J. Resilient Econ. 2021, 1, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikutienė, R.; Slušnienė, G. Pagrindiniai darbo atmosferos kokybę ikimokyklinio ugdymo įstaigoje lemiantys veiksniai. Stud. Verslas Visuomenė Dabart. Ir Ateities Įžvalgos 2021, VI, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, A. Teacher collaboration: 30 years of research on its nature, forms, limitations and effects. Teach. Teach. 2019, 25, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, D. Intellectual and physical shared workspace: Professional learning communities and the collaborative culture. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2017, 32, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkutė, J.; Valinevičienė, G. Oficialaus ir paslėpto curriculum raiška aukštojo mokslo studijų edukacinėse aplinkose taikant mokymosi bendradarbiaujant principus [Manifestation of higher education official and hidden curriculum applying principles of collaborative learning in educational environment design]. Tiltai 2018, 1, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Topping, K.; Wolfendale, S. (Eds.) Parental Involvement in Children’s Reading, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perc, M.; Jordan, J.; Rand David, G.; Wang, Z.; Boccaletti, S.; Szolnoki, A. Statistical Physics of Human Cooperation. Phys. Rep. 2017, 687, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juknevičienė, V.; Bersėnaitė, J. Sąveikaujantis valdymas kaip verslo ir mokslo bendradarbiavimo dėl inovacijų plėtotės prielaida. Public Policy Adm. 2016, 15, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stulgiene, A.; Ciutiene, R. Collaboration in the project team. Econ. Manag. 2014, 19, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafta, A. Conceptualizing Workplace Conflict from Diverse Perspectives. J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 18, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, S. Formal collaboration and informal information flow. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 1992, 7, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callens, C.; Verhoest, K. Conditions for Successful Public-Private Collaboration for Public Service Innovation; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GHickey, G.M.; Roozee, E.; Voogd, R.; de Vries, J.R.; Sohns, A.; Kim, D.; Temby, O. On the architecture of collaboration in inter-organizational natural resource management networks. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 328, 116994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.; Van Wyk, R.; Dhanpat, N. Exploring Practices for Effective Collaboration. 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/307638839_EXPLORING_PRACTICES_FOR_EFFECTIVE_COLLABORATION (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Putnam, R.D. Democracies in Flux: The Evolution of Social Capital in Contemporary Society; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Woolcock, M. Social Capital and Economic Development: Toward a Theoretical Synthesis and Policy Framework. Theory Soc. 1998, 27, 151–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, M.; Doherty, P.; Kinder, K. Multi-agency working: Models, challenges and key factors for success. J. Early Child. Res. 2005, 3, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieley, J. Overcoming the Barriers to Effective Collaboration. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2014, 33, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agranoff, R. Inside Collaborative Networks: Ten Lessons for Public Managers. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66 (Suppl. 1), 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwi, V.; Nwosu, F. Success Factors in Collaborative Assets, Resources, and Knowledge Combination in Organizations. Resour. Knowl. Comb. Organ. 2019, 1, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monios, J.; Rye, T.; Hrelja, R.; Isaksson, K.; Scholten, C. The relationship between formal and informal institutions for governance of sustainable public transport. J. Transp. Geogr. 2016, 69, 196–206. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, C.; Lee, K.; Yoon, B.; Toulan, O. Typology and Success Factors of Collaboration for Sustainable Growth in the IT Service Industry. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, J.H. Success Factors of Inter-Firm Collaboration: Moderated Effects of Contextual Factors. Korean Acad. Assoc. Bus. 2007, 20, 913–937. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary, R.; Choi, Y.; Gerard, C. The Skill Set of the Successful Collaborator. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 72, S70–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, M.; Din, M. Collaboration as 21st Century Learning Skill at Undergraduate Level. Sir Syed J. Educ. Soc. Res. (SJESR) 2023, 6, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, D. Thinking together and alone. Educ. Res. 2015, 44, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.S.; Ahmad, M.O.; Majava, J. Industry 4.0 and sustainable development: A systematic mapping of triple bottom line, Circular Economy and Sustainable Business Models perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297, 126655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, C.J.; Tremblay, D.; Cazabon-Sansfaçon, L. The role of social actors in advancing a green transition: The case of Quebec’s cleantech cluster. J. Innov. Econ. Manag. 2017, 3, 63–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucci, T.; Casprini, E.; Galati, A.; Zanni, L. The virtuous cycle of stakeholder engagement in developing a sustainability culture: Salcheto winery. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 119, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, U.; Kraslawski, A.; Huiskonen, J. Buyer-supplier relationship on social sustainability: Moderation analysis of cultural intelligence. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2018, 5, 1429346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawashdeh, A. The impact of green human resource management on organizational environmental performance in Jordanian health service organizations. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2018, 8, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giglio, E.M.; Ryngelblum, A.; Lopes de Sousa Jabbour, A.B. Relational governance in recycling cooperatives: A proposal for managing tensions in sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 121036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepic, M.; Omta, O.; Trienekens, J.; Fortuin, F. The role of structural and relational governance in creating stable innovation networks: Insights from sustainability-oriented Dutch innovation networks. J. Chain Netw. Sci. 2011, 11, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, S.; Moldogaziev, T. Employee empowerment, employee attitudes, and performance: Testing a causal model. Public Adm. Rev. 2013, 73, 490–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, G.; Barletta, I.; Stahl, B.; Taisch, M. Energy Management in Production: A novel Method to Develop Key Performance Indicators for Improving Energy Efficiency. Appl. Energy 2015, 149, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Ball, P. Steps towards sustainable manufacturing through modelling material, energy and waste flows. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 140, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiuncika, L.; Bormane, S. Sustainable Management of Manufacturing Processes: A Literature Review. Processes 2024, 12, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejaz, M.R. Smart Manufacturing as a Management Strategy to Achieve Sustainable Competitiveness. J. Knowl. Econ. 2023, 15, 682–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwibisa, N.; Majzoub, S. Challenges Faced in Inter-Organizational Collaboration Process. A Case Study of Region Skåne. J. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, B. Addressing Collaboration Challenges in Project-Based Learning: The Student’s Perspective. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Nakajima, T.; Sawada, R. Benefits and Challenges of Collaboration between Students and Conversational Generative Artificial Intelligence in Programming Learning: An Empirical Case Study. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Song, G.; Ghannam, R. Enhancing Teamwork and Collaboration: A Systematic Review of Algorithm-Supported Pedagogical Methods. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, O.S. Problem-Based Learning Innovation: Using Problems to Power Learning in the 21st Century; Gale Cengage Learning: Detroit, MI, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley, E.F.; Major, C.H.; Cross, K.P. Collaborative Learning Techniques: A Handbook for College Faculty; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Ouyang, F.; Chen, W. Examining the effect of a genetic algorithm-enabled grouping method on collaborative performances, processes, and perceptions. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2022, 34, 790–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.M.; Kuo, C.H. An optimized group formation scheme to promote collaborative problem-based learning. Comput. Educ. 2019, 133, 94–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhlis, M.; Perdana, R. A Critical Analysis of the Challenges of Collaborative Governance in Climate Change Adaptation Policies in Bandar Lampung City, Indonesia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dapilah, F.; Nielsen, J.Ø.; Lebek, K.; Lise D’haen, S.A. He who pays the piper calls the tune: Understanding collaborative governance and climate change adaptation in Northern Ghana. Clim. Risk Manag. 2021, 32, 100306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, J.; Larsson, L. Integration, Application and Importance of Collaboration in Sustainable Project Management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, M.L.; Carvalho, M.M. The challenge of introducing sustainability into project management function: Multiple-case studies. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 117, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, N.; Park, S.H.; Park, S. Partnership-Based Supply Chain Collaboration: Impact on Commitment, Innovation, and Firm Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessens, Z.; Lammens, M.; Barbier, L.; Huys, I. Opportunities and Challenges in Cross-Country Collaboration: Insights from the Beneluxa Initiative. J. Mark. Access Health Policy 2024, 12, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahapiet, J.; Sumantra, G. Social Capital, Intellectual Capital, and the Organizational Advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, R.; Rebele, R.; Grant, A. Collaborative overload. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2016, 94, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, R.; Gray, P. Where Has the Time Gone? Addressing CollaborationOverload in a Networked Economy. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2013, 56, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sull, D.; Sull, C.; Bersin, J. Five ways leaders can support remote work. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2020, 61, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, D.; Kurland, N. A Review of Telework Research: Findings, New Directions, and Lessons for the Study of Modern Work. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 250–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, P.; Mortensen, M. Understanding Conflict in Geographically Distributed Teams: The Moderating Effects of Shared Identity, Shared Context, and Spontaneous Communication. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 290–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piras, G.; Muzi, F.; Tiburcio, V.A. Enhancing Space Management through Digital Twin: A Case Study of the Lazio Region Headquarters. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Jia, R. Exploring the Interplay of the Physical Environment and Organizational Climate in Innovation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iovescu, D.; Tudose, C. Real-Time Document Collaboration—System Architecture and Design. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druta, R.; Druta, C.; Negirla, P.; Silea, I. A Review on Methods and Systems for Remote Collaboration. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; Jeong, Y.; Lee, K.; Lee, S.; Yoon, B. Technology-Based New Service Idea Generation for Smart Spaces: Application of 5G Mobile Communication Technology. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lottaz, C. Collaborative Design Using Solution Spaces. Doctoral Dissertation, Swiss Federal Technology Institute of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratton, L.; Erickson, T.J. 8 ways to build collaborative teams. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 85, 100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kahn, A.W. Psychological Conditions of Personal Engagement and Disengagement At Work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, J.; Singh, H. The Relational View: Cooperative Strategy and Sources of Interorganizational Competitive Advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 660–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diani, R.; Anggoro, B.; Suryani, E. Enhancing problem-solving and collaborative skills through RICOSRE learning model: A socioscientific approach in physics education. J. Adv. Sci. Math. Educ. 2023, 3, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.; Vista, A.; Scoular, C.; Awwal, N.; Griffin, P.; Care, E. Automatic coding procedures for collaborative problem solving. In Assessment and Teaching of 21st Century Skills: Methods and Approach; Griffin, P., Care, E., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 115–132. [Google Scholar]

- Baranes, A.F.; Oudeyer, P.Y.; Gottlieb, J. The effects of task difficulty, novelty and the size of the search space on intrinsically motivated exploration. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, N.J.; Salas, E.; Kiekel, P.A.; Bell, B. Advances in measuring team cognition. In Team Cognition: Understanding the Factors That Drive Process and Performance; Salas, E., Fiore, S.M., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; pp. 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- Dillenbourg, P.; Traum, D. Sharing solutions: Persistence and grounding in multi-modal collaborative problem solving. J. Learn. Sci. 2006, 15, 121–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, P.; Care, E.; Wilson, M. Measuring Individual and Group Performance in Collaborative Problem Solving; Discovery Project DP160101678; University of Melbourne Australian Research Council: Melbourne, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lertcharoenrit, T. Enhancing Collaborative Problem-Solving Competencies by Using STEM-Based Learning Through the Dietary Plan Lessons. J. Educ. Learn. 2020, 9, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Ruan, X.; Feng, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Xiong, B. Research on Online Collaborative Problem-Solving in the Last 10 Years: Current Status, Hotspots, and Outlook—A Knowledge Graph Analysis Based on CiteSpace. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-H.; Tsai, P.-L.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Huang, W.-C.; Hsieh, P.-J. Exploring Collaborative Problem Solving Behavioral Transition Patterns in Science of Taiwanese Students at Age 15 According to Mastering Levels. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S. Effects of Search Strategies on Collective Problem-Solving. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Bao, H.; Shen, J.; Zhai, X. Investigating Sequence Patterns of Collaborative Problem-Solving Behavior in Online Collaborative Discussion Activity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetroulis, E.A.; Papadogiannis, I.; Wallace, M.; Poulopoulos, V.; Theodoropoulos, A.; Vasilopoulos, N.; Antoniou, A.; Dasakli, F. Collaboration Skills and Puzzles: Development of a Performance-Based Assessment—Results from 12 Primary Schools in Greece. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, J.; Gilchrist, D. Designing the Collaboration and Its Operational Framework; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvert, K. Collaborative Leadership: Cultivating an Environment for Success. Collab. Librariansh. 2018, 10, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Bolman, L.G.; Deal, T.E. Reframing Organizations: Artistry, Choice, and Leadership; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bal, P.; De Lange, A. From flexibility human resource management to employee engagement and perceived job performance across the lifespan: A multisample study. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 88, 126–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartigan, K.L. Effective Leadership Through Effective Communication. Instr. Des. Capstones Collect. 2024, 87. Available online: https://scholarworks.umb.edu/instruction_capstone/87 (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Erbay, M.; Javed, M.; Nelson, J.; Benzerroug, S.; Karkkulainen, E.; Christian, E.; Enriquez, C.E. The Relationship Between Leadership and Communication, and the Significance of Efficient Communication in Online Learning. Educ. Adm. Theory Pract. J. 2024, 30, 2065–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, D. Effective Leadership is all about Communicating Effectively: Connecting Leadership and Communication. Int. J. Manag. Bus. Stud. 2015, 5, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlova, S. Organizational culture and organizational behavior of higher education institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Appl. Econ. 2023, 20, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Huamán, H.I.; Medina-Valderrama, C.J.; Valencia-Arias, A.; Vasquez-Coronado, M.H.; Valencia, J.; Delgado-Caramutti, J. Organizational Culture and Teamwork: A Bibliometric Perspective on Public and Private Organizations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ríos, C.Y.; Narváez, A.C.; Jiménez, S.C. Application of the CERT Values Measurement Model for Organizational Culture in the Management and Quality Company. In Communications in Computer and Information Science, 1431 CCIS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 399–408. [Google Scholar]

- Srisathan, W.A.; Ketkaew, C.; Naruetharadhol, P. The intervention of organizational sustainability in the effect of organizational culture on open innovation performance: A case of thai and chinese SMEs. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1717408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assoratgoon, W.; Kantabutra, S. Toward a sustainability organizational culture model. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 400, 136666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicea, C.; Țurlea, C.; Marinescu, C.; Pintilie, N. Organizational culture: A concept captive between determinants and its own power of influence. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhengiz, T.; Hockerts, K. Dogmatic, instrumental and paradoxical frames: A pragmatic research framework for studying organizational sustainability. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2022, 24, 501–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyton, J. Communication and Organizational Culture: A Key to Understanding Work Experience; Sage Publications: New York, HY, USA, 2010; ISBN 9781412980227. [Google Scholar]

- Bostanli, L.; Habisch, A. Narratives as a Tool for Practically Wise Leadership. Humanist. Manag. J. 2023, 8, 113–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musheke, M.M.; Phiri, J. The Effects of Effective Communication on Organizational Performance Based on the Systems Theory. Open J. Bus. Manag. 2021, 9, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Yu, S.-C. The Moderating Effect of Cross-Cultural Psychological Adaptation on Knowledge Hiding and Employee Innovation Performance: Evidence from Multinational Corporations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhodary, D.A. Exploring the Relationship between Organizational Culture and Well-Being of Educational Institutions in Jordan. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.M. The Value of Employee Wellbeing. Public Health Rep. 2019, 134, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larik, A.; Shah Bukhari, S.; Qureshi, S. Role of Organizational Culture in Improving Employee Psychological Ownership. Pak. J. Appl. Soc. Sci. 2023, 14, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangeline, E.T.; Ragavan, V.P. Organisational Culture and Motivation as Instigators for Employee Engagement. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Q.; Wang, Y. Collaborative Leadership, Collective Action, and Community Governance against Public Health Crises under Uncertainty: A Case Study of the Quanjingwan Community in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Orabi, T.; Almasarweh, M.S.; Qteishat, M.K.; Qudah, H.A.; AlQudah, M.Z. Mapping Leadership and Organizational Commitment Trends: A Bibliometric Review. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jin, X. Exploring the Role of Shared Leadership on Job Performance in IT Industries: Testing the Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, D.V.; Dannhäuser, L. Reconsidering Leadership Development: From Programs to Developmental Systems. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, M.; Cleveland, S. Building Engaged Communities—A Collaborative Leadership Approach. Smart Cities 2018, 1, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeshu, P.; Fernando, T.; Therrien, M.-C.; Keraminiyage, K. Inter-Organisational Collaboration Structures and Features to Facilitate Stakeholder Collaboration. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalouf, G. Effects of collaborative leadership on organizational performance. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Dev. 2019, 6, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angana, G.; Chiroma, J. Collaborative Leadership and its Influence in Building and Sustaining Successful Cross-Functional Relationships in Organizations in Kenya. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2021, 23, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, M. The effects of collaborative cultures and knowledge sharing on organizational learning. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2018, 31, 1138–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s) | Definition |

|---|---|

| Mikutienė, R., Slušnienė, G. (2021) [64] | Collaboration is defined as social interaction that creates a new democratic culture in all areas of social life. |

| Hargreaves, A. (2019) [65] | Collaboration is a form of social interaction used to organize joint partner activities, align actions, unify individual efforts, and develop systems of cooperation, as well as foster relationships of social collaboration and mutual assistance. |

| Carpenter, D. (2018) [66] | Collaboration means absolute equality, mutual respect, sharing knowledge, and information. It involves seeking the best work methods and collective decision-making, recognizing the individuality of the family and the uniqueness of the child. |

| Valinevičienė, G., Starkutė, J. (2018) [67] | Collaboration is a phenomenon where a certain number of people with cognitive, social, and reflective abilities work together in homogeneous or heterogeneous groups, based on free will, towards a common goal. |

| Topping, K., Wolfendale, S. (2017) [68] | Collaboration is the pursuit of a common goal, sharing tasks, and aligning different attitudes and interests. |

| Perc, M., Jordan, J.J., Rand, D.G. (2017) [69] | Collaboration is typical among individuals who are willing to sacrifice personal gain for a common goal and work together to achieve what they cannot accomplish alone. |

| Juknevičienė, V., Bersėnaitė, J. (2016) [70] | Collaboration is the process by which organizations’ capabilities, intellectual potential, and competencies interact and are utilized to make joint decisions, carry out activities, and achieve a common goal while adhering to shared rules, norms, principles, and values. |

| Stulgienė, A., Ciutienė, R. (2014) [71] | Collaboration is a relationship between two or more parties working together to achieve common goals. It is similar to teamwork, but it goes beyond simply working together—it is a philosophy. |

| Factors Determining Collaboration Success | Barriers to Successful Collaboration |

|---|---|

| Identifying shared goals | Susceptibility to external disruptions |

| Acknowledging shared accountability | Self-interested behavior |

| Maintaining balanced power dynamics | Complexity of interactions or high transaction expenses |

| Readiness to share data and resources | Divergent perceptions of risks and varying levels of risk tolerance |

| Establishing clear expectations, commitments, and defined roles | Uneven distribution of costs and benefits |

| Implementing evaluation and feedback mechanisms | Cultural or organizational challenges to maintaining control |

| Resolving conflicts effectively | Unstable membership or frequent staff turnover |

| Key Values and Mission | Sustainability-Based Leadership | Employee Empowerment | Fostering an Innovation Culture | Community Engagement | Promoting Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) | Adaptability to Sustainability Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The organization defines success not only by financial outcomes but also by its social and environmental impact. | Employees actively participate in and support sustainability initiatives, demonstrating a commitment to these principles. Leadership involves employees in decision-making processes. | Employees are empowered to take responsibility for sustainability initiatives and are encouraged to lead efforts that align with the company’s sustainability goals. | Innovation culture is encouraged, meaning that employees are motivated to collaborate on creative solutions to sustainability challenges. | Collaboration with stakeholders ensures that sustainability efforts align with broader societal goals and community needs. | CSR practices are integrated into the business model, ensuring the organization contributes positively to society and the environment. | The organization is structured to be adaptable, allowing it to quickly respond to emerging sustainability challenges and opportunities. |

| Additional Information | Sustainability goals are integrated into all business processes—from product design and development to supply chain management and customer service. | Employees are given the resources, training, and authority to initiate and manage sustainability projects within their areas of expertise. | The organization supports risk-taking and experimentation in sustainability-related innovations, fostering a culture of continuous improvement. | Regular dialog and partnerships with community groups, local governments, and NGOs strengthen the organization’s commitment to sustainability. | CSR programs are transparent, regularly reviewed, and aligned with both corporate and societal goals for long-term impact. | Adaptability mechanisms include scenario planning, proactive risk assessments, and a culture of flexibility, ensuring that organizations are prepared to tackle sustainability challenges. |

| Problem | Solution for Managers |

|---|---|

| 1. Collaboration Resources: Employees contribute resources in three categories—informational, social, and personal. Each is important, but valued differently, as some require more effort, time, and energy than others. | Simplify and distribute responsibilities equally: Ensure that the burden is shared fairly among team members. Recognize and reward contributions based on the value and effort of the resources provided. |

| 2. Time Management for Collaboration: Overworking employees with too much collaboration can lead to burnout, stress, and fatigue. It is crucial to monitor how much time employees spend working collaboratively. | Track collaboration time: Use a calendar where both employees and managers can monitor the time spent on collaboration. This helps employees balance their workload and prevents burnout, while allowing managers to observe contributions and ensure proper workload distribution. |

| 3. Employee Behavior: Employees may struggle to make decisions, refuse or challenge tasks, or contribute meaningfully, depleting their resources and reducing their willingness to collaborate. | Encourage decision-making autonomy: Leaders should encourage employees to make their own decisions, allow them to refuse tasks, and provide guidance on prioritization. They should also help to connect employees with those who can contribute more efficiently to the collaboration. |

| 4. Difficulty Sharing Resources: Transferring informational and social resources can be time-consuming, delaying collaborative work. | Utilize technology: Implement tools such as software programs or websites to streamline communication and resource sharing. Designate physical spaces dedicated to different collaborative tasks to increase efficiency. |

| 5. Overburdening a Key Collaborator: One highly involved employee may be overloaded with tasks, preventing others from fully participating in collaboration. | Restructure decision-making rights: Shift decision-making authority to the appropriate individuals, and ensure tasks are distributed across the team, rather than relying too much on a single employee. Focus on a balanced distribution of responsibilities among all members. |

| Problem-Solving Process Steps | Description and Expansion |

|---|---|

| 1. Discover and Understand the Problem | Identify and analyze the collaboration process to determine what is hindering effective teamwork. This step involves gathering data, observations, and feedback to fully grasp the issue. |

| 2. Clearly Define the Problem | Clearly articulate the specific problem that is obstructing collaboration. A precise definition helps focus the team’s efforts and avoid misinterpretation of the issue. |

| 3. Investigate the Problem | Examine the root cause of the problem. Determine where the issue originated, how it developed, and what factors are associated with the collaboration breakdown. |

| 4. Select a Solution | Identify the best possible solution. Evaluate the potential impact of various options, consider their feasibility, and choose the approach that can drive the most significant change. |

| 5. Implement the Solution | Commit to executing the chosen solution. Be prepared to face challenges and obstacles during implementation, especially those related to behavior change or process adjustments. |

| 6. Review the Results | Assess whether the desired collaboration outcome has been achieved. Determine if the problem has been fully resolved or if additional adjustments are necessary to refine the solution. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ispiryan, A.; Pakeltiene, R.; Ispiryan, O.; Giedraitis, A. Fostering Organizational Sustainability Through Employee Collaboration: An Integrative Approach to Environmental, Social, and Economic Dimensions. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 1806-1826. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia4040119

Ispiryan A, Pakeltiene R, Ispiryan O, Giedraitis A. Fostering Organizational Sustainability Through Employee Collaboration: An Integrative Approach to Environmental, Social, and Economic Dimensions. Encyclopedia. 2024; 4(4):1806-1826. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia4040119

Chicago/Turabian StyleIspiryan, Audrone, Rasa Pakeltiene, Olympia Ispiryan, and Algirdas Giedraitis. 2024. "Fostering Organizational Sustainability Through Employee Collaboration: An Integrative Approach to Environmental, Social, and Economic Dimensions" Encyclopedia 4, no. 4: 1806-1826. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia4040119

APA StyleIspiryan, A., Pakeltiene, R., Ispiryan, O., & Giedraitis, A. (2024). Fostering Organizational Sustainability Through Employee Collaboration: An Integrative Approach to Environmental, Social, and Economic Dimensions. Encyclopedia, 4(4), 1806-1826. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia4040119