The Evolution of ESG: From CSR to ESG 2.0

Definition

1. Introduction

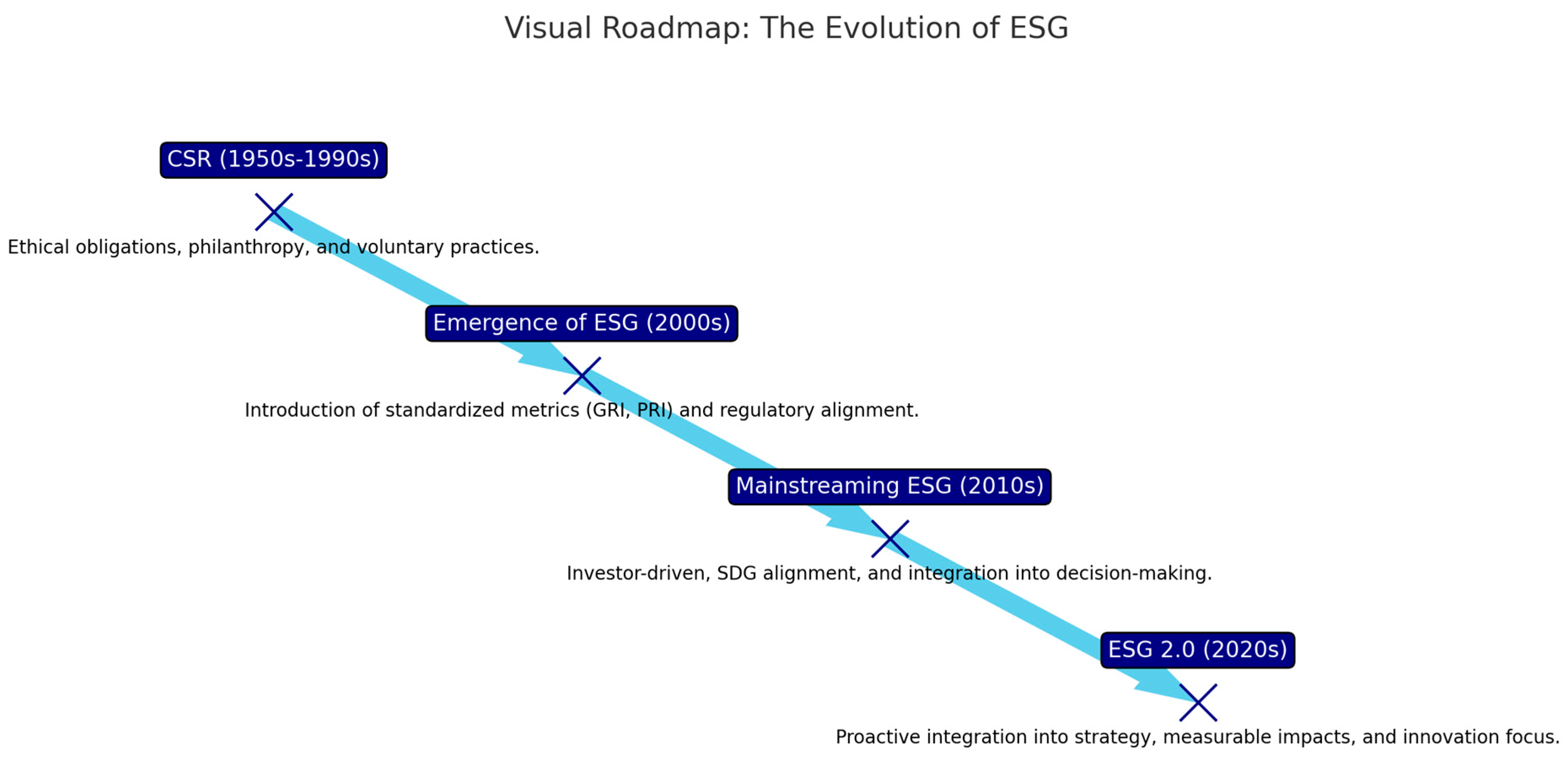

2. The Evolution

2.1. 1950s: The Birth of CSR

2.2. 1960s: Growing Awareness

2.3. 1970s: Formalizing Corporate Responsibility

2.4. 1980s: The Strategic Approach

2.5. 1990s: The Rise of Accountability

2.6. 2000s: The Emergence of ESG Metrics

2.7. 2010s: ESG Becomes Mainstream

2.8. 2020s: ESG 2.0 and Strategic Integration

3. Integrating ESG into Business Strategy

3.1. Why Context Matters

3.2. Stories of Success

3.3. Technology: A Helping Hand

4. ESG as a Driver of Innovation and Value Creation

5. Governance and Accountability in ESG 2.0

6. Challenges and Opportunities

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Farmaki, A. Corporate wokeness: An expanding scope of CSR? Tour. Manag. 2022, 93, 104623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: Taking another look. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2016, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D.; Moon, J. “Implicit” and “explicit” CSR: A conceptual framework for a comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, A. Global Versus Local CSR Strategies. Eur. Manag. J. 2006, 24, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, S.L.; Koch, A.; Starks, L.T. Firms and social responsibility: A review of ESG and CSR research in corporate finance. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 66, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, L.H.; Fitzgibbons, S.; Pomorski, L. Responsible investing: The ESG-efficient frontier. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 142, 572–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafeim, G. ESG: Hyperboles and Reality. SSRN Electron. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, B. Demystifying ESG: Its History & Current Status. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/betsyatkins/2020/06/08/demystifying-esgits-history--current-status/?sh=1cc02c72cdd3 (accessed on 7 September 2023).

- Zopounidis, C.; Garefalakis, A.; Lemonakis, C.; Passas, I. Environmental, social and corporate governance framework for corporate disclosure: A multicriteria dimension analysis approach. Manag. Decis. 2020, 58, 2473–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiny, A.; Taglialatela, J.; Testa, F.; Iraldo, F. Determinants of environmental social and governance (ESG) performance: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 456, 142213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, H. Social Responsibilities of the Businessman. Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/Social_Responsibilities_of_the_Businessm.html?hl=el&id=ALIPAwAAQBAJ (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- Passas, I. Accounting for Integrity: ESG and Financial Disclosures: The Challenge of Internal Fraud in Management Decision-Making. Ph.D. Thesis, Hellenic Mediterranean University, Heraklion, Greece, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés, M.; Agudelo, L.; Jóhannsdóttir, L.; Davídsdóttir, B. A literature review of the history and evolution of corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2019, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Library of Congress. The Civil Rights Movement|The Post-War United States, 1945–1968|U.S. History Primary Source Timeline. Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/post-war-united-states-1945-1968/civil-rights-movement/ (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Ware, L. Civil Rights and the 1960s: A Decade of Unparalleled Progress. Md. Law Rev. 2013, 72, 1087. Available online: https://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr/vol72/iss4/4 (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Murphy, P.E. Corporate social responsiveness: An evolution. Univ. Mich. Bus. Review. 1978, 17, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K. Can business afford to ignore social responsibilities? Calif. Manag. Rev. 1960, 2, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silent Spring|Rachel Carson’s Environmental Classic|Britannica. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Silent-Spring (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The Competitive Advantage of Corporate Philanthropy. Available online: https://hbr.org/2002/12/the-competitive-advantage-of-corporate-philanthropy (accessed on 13 September 2023).

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A. Firm size, organizational visibility and corporate philanthropy: An empirical analysis. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2006, 15, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadarajan, P.R.; Menon, A. Cause-Related Marketing: A Coalignment of Marketing Strategy and Corporate Philanthropy. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.; Parc, J.; Yim, S.; Park, N. An extension of Porter and Kramer’s Creating Shared Value (CSV): Reorienting Strategies and Seeking International Cooperation. J. Int. Area Stud. 2011, 18, 49–64. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43111578 (accessed on 13 September 2023).

- Mendy, J. Supporting the creation of shared value. Strateg. Chang. 2019, 28, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembek, K.; Singh, P.; Bhakoo, V. Literature review of shared value: A theoretical concept or a management buzzword? J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 137, 231–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menghwar, P.S.; Daood, A. Creating shared value: A systematic review, synthesis and integrative perspective. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 466–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A.; Palazzo, G.; Spence, L.J.; Matten, D. Contesting the value of “creating shared value”. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2014, 56, 130–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, K.; Paine, W.S. Johnson & Johnson: An Ethical Analysis of Broken Trust. Available online: https://www.nabet.us/Archives/2011/NABET_Proceedings_2011.pdf#page=163 (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Eaddy, L.L. Johnson & Johnson’s Recall Debacle. Available online: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2194/ (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Benson, J.A. Crisis revisited: An analysis of strategies used by Tylenol in the second tampering episode. Cent. States Speech J. 1988, 39, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laplume, A.O.; Sonpar, K.; Litz, R.A. The stakeholder theory. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 1152–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, B.L.; Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.C.; Purnell, L.; de Colle, S. Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2010, 4, 403–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchell, J.; Cook, J. Sleeping with the Enemy? Strategic Transformations in Business-NGO Relationships Through Stakeholder Dialogue. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 113, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glambosky, M.; Jory, S.R.; Ngo, T. Stock market response to the statement on the purpose of a corporation: A vindication of stakeholder theory. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2023, 31, 892–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballinger, J. Nike Chronology. 1988. Available online: https://depts.washington.edu/ccce/polcommcampaigns/NikeChronology.htm (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Grubb, M.; Koch, M.; Thomson, K.; Sullivan, F.; Munson, A. The ‘Earth Summit’ Agreements: A Guide and Assessment: An Analysis of the Rio ’92 UN Conference on Environment and Development; 2019. Available online: https://www.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=cS6ODwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT10&dq=1992+Earth+Summit+in+Rio+de+Janeiro+&ots=Tw-EJGF77S&sig=Z1zQrZGyrffJp_VZG7Airt2-YmI (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Vaillancourt, J. Earth Summits of 1992 in Rio. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/08941929309380810 (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Utting, P. Sustainability, accountability and corporate governance: Exploring multinationals’ reporting practices. Dev. Chang. 2008, 39, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergsteiner, H.; Avery, G.C. A theoretical responsibility and accountability framework for CSR and global responsibility. J. Glob. Responsib. 2010, 1, 8–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendell, J. In whose name? The accountability of corporate social responsibility. Dev. Pract. 2005, 15, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, W.C. Corporation, Be Good!: The Story of Corporate Social Responsibility; Dog Ear Publishing: Carmel, IN, USA, 2006; p. 334. [Google Scholar]

- Fiaschi, D.; Giuliani, E.; Nieri, F.; Salvati, N. How bad is your company? Measuring corporate wrongdoing beyond the magic of ESG metrics. Bus Horiz. 2020, 63, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GRI. GRI—Mission & History. GRI. 2022. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/about-gri/mission-history/ (accessed on 19 September 2023).

- UNPRI. Enhance our Global Footprint|PRI Web Page|PRI. 2021. Available online: https://www.unpri.org/annual-report-2021/how-we-work/building-our-effectiveness/enhance-our-global-footprint (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- PRI. PRI Reporting Framework 2018 Strategy and Governance; PRI Association: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelrehim, N.; Maltby, J. Narrative reporting and crises: British Petroleum and Shell, 1950–1958. Account. Hist. 2015, 20, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perceval, C. Towards a Process View of the Business Case for Sustainable Development: Lessons from the Experience at BP and Shell. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/jcorpciti.9.117.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Li, M.; Trencher, G.; Asuka, J. The clean energy claims of BP, Chevron, ExxonMobil and Shell: A mismatch between discourse, actions and investments. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passas, I.; Ragazou, K.; Zafeiriou, E.; Garefalakis, A.; Zopounidis, C. ESG Controversies: A Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis for the Sociopolitical Determinants in EU Firms. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, K.H.; El Ghoul, S.; Gong, Z.J.; Guedhami, O. Does CSR matter in times of crisis? Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 67, 101876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, A.; Frost, T.; Cao, H. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) disclosure: A literature review. Br. Account. Rev. 2023, 55, 101149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SDG. THE 17 GOALS|Sustainable Development. 2023. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 27 September 2023).

- Berg, F.; Kölbel, J.F.; Rigobon, R. Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. Rev. Financ. 2022, 26, 1315–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y. Can ESG Ratings impact Accounting Performance: Evidence from Chinese Companies. Highlights Bus. Econ. Manag. 2023, 18, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, L.L.; Fikru, M.; Vichitsarawong, T. Comparing the informativeness of sustainability disclosures versus ESG disclosure ratings. Sustain. Account. Manag. Pol. J. 2022, 13, 494–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crifo, P.; Diaye, M.A.; Oueghlissi, R. The effect of countries’ ESG ratings on their sovereign borrowing costs. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2017, 66, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A History of Corporate Social Responsibility: Concepts and Practices. In The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, W. In Search of the Lace Curtain: Residential Mobility, Class Transformation, and Everyday Practice among Buffalo’s Irish, 1880–1910. J. Urban Hist. 2009, 35, 970–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. COVID-19 and ESG preferences: Corporate bonds versus equities. Int. Rev. Financ. 2022, 22, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göker, A.; Sköld, J. The Impact of ESG During COVID-19 A Quantitative Study Targeting ESG and Stock Returns on the Swedish Stock Market During COVID-19. Master’s Thesis, Gothenburg University, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pástor, Ł.; Vorsatz, M.B. Mutual Fund Performance and Flows during the COVID-19 Crisis. Rev. Asset Pricing Stud. 2020, 10, 791–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourgiantakis, M.; Apostolakis, A.; Dimou, I. COVID-19 and holiday intentions: The case of Crete, Greece. Anatolia 2021, 32, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Geng, X. The role of ESG performance during times of COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giunipero, L.C.; Denslow, D.; Rynarzewska, A.I. Small business survival and COVID-19—An exploratory analysis of carriers. Res. Transp. Econ. 2022, 93, 101087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, H.K.; Chen, Y.C.; Wu, T.J.; Ting, L.H.; Cheng, H.E.; Hsu, K.T. Exploring Microsoft Data Center Innovations: From Earth to Outer Space, Unveiling Transformations and Corporate Social Responsibility. Available online: http://dspace.fcu.edu.tw/handle/2376/4918 (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Buchal, R. Using Microsoft Teams to Support Collaborative Knowledge Building in the Context of Sustainability Assessment. Available online: https://ojs.library.queensu.ca/index.php/PCEEA/article/view/13882 (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Michel, G.M.; Feori, M.; Damhorst, M.L.; Lee, Y.A.; Niehm, L.S. Examining sustainable supply chain management via a social-symbolic work lens: Lessons from Patagonia. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2019, 48, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattalino, F. Circular advantage anyone? Sustainability-driven innovation and circularity at Patagonia, Inc. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 60, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheyden, T.; Eccles, R.G.; Feiner, A. ESG for all? The impact of ESG screening on return, risk, and diversification. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2016, 28, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado Muci de Lima, I.; Costa Fernandes, D. ESG 2.0: The New Perspectives for Human Rights Due Diligence. In Building Global Societies Towards an ESG World; CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajavuori, M.; Savaresi, A.; van Asselt, H. Mandatory due diligence laws and climate change litigation: Bridging the corporate climate accountability gap? Regul. Gov. 2023, 17, 944–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, J.L.; Kwan, G.T.; Ottoboni, G.R.; McCaffrey, M.S. From the suites to the streets: Examining the range of behaviors and attitudes of international climate activists. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 72, 101866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vortelinos, D.; Menegaki, A.; Passas, I.; Garefalakis, A.; Viskadouros, G. Heterogeneous Responses of Energy and Non-Energy Assets to Crises in Commodity Markets. Energies 2024, 17, 5438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Inter-market variability in CO2 emission-intensities in tourism: Implications for destination marketing and carbon management. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.Y. Decomposition of tourism greenhouse gas emissions: Revealing the dynamics between tourism economic growth, technological efficiency, and carbon emissions. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albitar, K.; Borgi, H.; Khan, M.; Zahra, A.K. Business environmental innovation and Co2 emissions: The moderating role of environmental governance. Bus Strategy Environ. 2022, 32, 1996–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, D.; Strand, R. Patagonia: Driving sustainable innovation by embracing tensions. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2017, 60, 102–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, J.; Rasche, A.; Kenny, K. Sustainability as Opportunity: Unilever’s Sustainable Living Plan. Manag. Sustain. Bus. 2019, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.E.; Murphy, C.E. Sustainable Living: Unilever. In Progressive Business Models: Creating Sustainable and Pro-Social Enterprise; Palgrave Studies in Sustainable Business In Association with Future Earth; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Part F1859; pp. 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, N.; Ormiston, J. Blockchain as a sustainability-oriented innovation?: Opportunities for and resistance to Blockchain technology as a driver of sustainability in global food supply chains. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 175, 121403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böckel, A.; Nuzum, A.K.; Weissbrod, I. Sustainable Production and Consumption Blockchain for the Circular Economy: Analysis of the Research-Practice Gap. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 25, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenberg, D.; Chappe, R.; Feldman, A. ESG 2.0: Measuring & Managing Investor Risks Beyond the Enterprise-level. 2021. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3820316 (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Radu, O.; Dragomir, V.D.; Ionescu-Feleagă, L. The link between corporate ESG performance and the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Proc. Int. Conf. Bus. Excell. 2023, 17, 776–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitlarp, T.; Kiattisin, S. The impact factors of industry 4.0 on ESG in the energy sector. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baue, B.; Murninghan, M. The accountability web: Weaving corporate accountability and interactive technology. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2010, 41, 27–49. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/jcorpciti.41.27.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Kazakov, A.; Denisova, S.; Barsola, I.; Kalugina, E.; Molchanova, I.; Egorov, I.; Kosterina, A.; Tereshchenko, E.; Shutikhina, L.; Doroshchenko, I.; et al. ESGify: Automated Classification of Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance Risks. Dokl. Math. 2023, 108, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, S.N.; Kuznetsov, V.P.; Smirnova, Z.V.; Andryashina, N.S.; Romanovskaya, E.V. Corporate Governance in the ESG Context: A New Understanding of Sustainability. In Ecological Footprint of the Modern Economy and the Ways to Reduce It: The Role of Leading Technologies and Responsible Innovations; Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Part F2356; pp. 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handoyo, S.; Anas, S. The effect of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) on firm performance: The moderating role of country regulatory quality and government effectiveness in ASEAN. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2371071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzey, C.; Al-Shaer, H.; Karaman, A.S.; Uyar, A. Public governance, corporate governance and excessive ESG. Corp. Gov. 2023, 23, 1748–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marais, M.; Reynaud, E.; Vilanova, L. Marketing strategies at the bottom of the pyramid: Examples from Nestlé, Danone, and Procter & Gamble. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2018, 17, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Yusta, A.; Méndez-Aparicio, M.D.; Jiménez-Zarco, A.I.; Martínez-Ruíz, M.P. When Responsible Production and Consumption Matter: The Case of Danone. In Responsible Consumption and Sustainability: Case Studies from Corporate Social Responsibility, Social Marketing, and Behavioral Economics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarelli, M.; Cosimato, S.; Landi, G.; Iandolo, F. Socially responsible investment strategies for the transition towards sustainable development: The importance of integrating and communicating ESG. TQM J. 2021, 33, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Passas, I. The Evolution of ESG: From CSR to ESG 2.0. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 1711-1720. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia4040112

Passas I. The Evolution of ESG: From CSR to ESG 2.0. Encyclopedia. 2024; 4(4):1711-1720. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia4040112

Chicago/Turabian StylePassas, Ioannis. 2024. "The Evolution of ESG: From CSR to ESG 2.0" Encyclopedia 4, no. 4: 1711-1720. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia4040112

APA StylePassas, I. (2024). The Evolution of ESG: From CSR to ESG 2.0. Encyclopedia, 4(4), 1711-1720. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia4040112