1. Introduction

Barcelona today is a thriving modern city of almost 5.7 million in 2024, renowned for its progressive approach to urban renewal and utilisation of digital technologies in the provision of urban services. Its rich urban history includes the urban plan and science of Ildefonso Cerda [

1], seen by some as the father of modern urban planning, and the architectural creations of Antonio Gaudi and Lluís Domènech i Montaner, amongst others. As an urban space, it provides a unique blend of old city charm around the

Ramblas, and the polycentric development of the 19th century

ensanche, the city expansion beyond the old medieval walls, based on the unique eight-sided

manzanas (blocks), dotted with modern service infrastructure and architectural gems such as the

Sagrada Familia cathedral. It is seen by many as a modern city

par excellence, and some authors see in its urban management a “Barcelona model” that differentiates the city from other major urban centres [

2].

However, at the time of the death of Franco in 1975—marking the end of an era of dictatorship and the start of the transition to democracy—the urban landscape in Barcelona was somewhat different. There remained several shantytowns, areas of illegal dwellings constructed in the main by the residents themselves, with the individual dwellings usually called

barracas or

coreas. UN-Habitat [

3] defines a shantytown as an illegal or unauthorised settlement characterised by substandard housing made up of plastic sheets, corrugated metal, or cardboard boxes.

Camino et al. [

4] (p. 18), however, suggest the term may include more substantial structures, seeing shanty developments as representing “a process of informal appropriation of land to build substandard housing (without prior planning for the land, lacking infrastructure, built with wood, mud, brick and/or recycled materials) as a spontaneous response to a lack of accessible housing in urban areas”. In this context, a

corea is sometimes seen as a sturdier structure than a

barraca, and usually a little larger, generally made of brick and cement and may even have a tiled roof, almost akin to a tiny bungalow. The two terms are often used interchangeably and here we will use the term

barraca in the main.

In a wider context, shantytowns are a global phenomenon, with some of the largest settlements found in India (Dharavi), Mexico (Ciudad Neza), and Pakistan (Orangi). Most of these shanties started life as the type of sub-standard dwellings noted above, rapidly put together by the inhabitants themselves, and generally devoid of adequate services. Over time, however, some of them have been improved to a significant degree by the residents, often working with local authorities, NGOs, and community organisations.

Not only have services such as water, electricity, and sewage systems been installed, but schools and community centres have been provided, and the dwellings themselves have been upgraded. In a few instances—as is the case in the Los Olivos neighbourhood in Lima, Peru—the shantytown has been transformed to such a degree that it has become an established community and part of the formal urban fabric of the city [

5]. Today, some authors [

6] view upgraded shantytowns as a viable solution to housing shortages in major cities.

In Europe, the growth of shanty developments in the 20th century can be viewed as a feature of post-industrialisation and the associated mass country–city migration. As Vorms [

7] (para. 2) notes, “the period of intense urbanization between the 1920s and 1960s was accompanied, especially in the cities of Southern Europe, with the development of poor peripheries that lacked facilities and services, and consisted of small fragile buildings built in violation of regulations. A new lexicon appeared everywhere to designate these materially and legally precarious neighborhoods:

bidonvilles in France,

baracche in Rome,

chabolas (shacks) in Madrid, and

barracas in Barcelona”. Vorms [

7] (para. 1) also observes that “as sites of an impoverished and difficult life, they embodied the flip side of this period of widespread improvement in living conditions”.

Barcelona attracted large numbers of workers in the early decades of the 20th century, and with limited attention being given to the housing problem by local or state authorities, the number of shanty dwellings tripled between 1914 and 1922, rising from 1218 to 3859 in this period [

8]. The situation was exacerbated when, in 1929, the port development authority—the Zona Franca Consortium—obtained the houses and land around the southern side of Montjuïc (the hill overlooking the city from the southwest) through compulsory purchase, forcing the residents—largely fishermen and unskilled labourers—to construct their own residences.

From then on,

barracas became a feature of the city, with up to 20,000 existing in the 1950s in the Barcelona municipality alone. “Shantyism in Barcelona, an urban phenomenon which unfolded over the course of the 20th century, created an informal city beside the planned city …. This informal city extended across Montjuïc hill and along the seafront, occupying both the hills and some interstitial spaces on the periphery of the

Ensanche” [

9] (p. 3).

Following this introductory section,

Section 2 examines some of the housing policy issues that shaped the treatment of the shantytowns by local and central housing authorities, and briefly discusses other aspects of shantytown studies.

Section 3 then focuses on some of the main shantytowns that remained in Barcelona in the 1970s and provides a brief account of their origin, development, and final demolition, drawing on secondary sources and photographs taken at the time. This approach is thus based on first-hand observation, photographic evidence, and a review of related literature. Finally,

Section 4 provides a summary of findings and an overall conclusion to the study.

2. Background

Between 1953 and 1958, 40,000 new housing units were built in the municipality of Barcelona, but as immigration alone created a demand for 50,000 new houses in these years, the pressure on the supply of housing was intense. Ferrer [

10] has drawn attention to the knock-on effects of the shanty developments in Barcelona and the adjoining municipalities, lacking in collective services, and exacerbating the problems of public transport, road infrastructure, schools, drainage, and parking. Other authors [

11] report that by the early 1960s, an estimated 100,000 people—seven percent of the population—lived in

barracas in the municipality of Barcelona alone. Against this backdrop, a number of initiatives were undertaken by the central state and local authorities to stimulate the housing market [

12], but also to intervene directly to re-house the shanty dwellers, mainly in rapidly constructed estates in dwellings of minimal dimensions in the city periphery.

In the early 1950s in Barcelona, shanty dwellers had been moved from Diagonal (one of the major cross-city routeways) to make way for the Eucharistic Congress of 1952. The displaced shanty dwellers were re-housed in the infamous Can Clos estate (

Figure 1), constructed by the

Patronato Municipal de la Vivienda (PMV—the Municipal Housing Authority) at the southern foot of Montjuïc, built in just 28 days—to house 3000 people. “The

barraquistas from Diagonal thought they had been brought to a concentration camp when they arrived to see the barbed wire fences. They were moved in lorries with their furniture, having been given five days’ notice of their resettlement. They were left in a wheat field and given the keys to their new houses and the wicks for the coal fires where they would have to cook. As there were not enough houses, two or three families had to inhabit each house.” [

13] (p. 41).

Thus started the process of re-homing shanty inhabitants and the demolition of their dwellings that would last several decades up until the close of the 20th century. During the “Slum Week” organised by the Church in 1957, it was estimated that there were 10,352 shanties in Barcelona. It was this development that led Bishop Modrego to talk of “them” and “us” at the “Week of the Suburb”, celebrated in Barcelona in 1957, referring to the 175,000 or more people living in the suburbs of the Barcelona municipality at the time, of which about a third lived in shanty developments [

14].

By the mid-1970s, two main areas of

barracas had been cleared—the Can Tunis shantytown on Montjuïc and the Somorrostro area on the beaches near the port, south of the old quarter of the city. On Montjuïc, the clearance was started in 1963 when Franco, whilst visiting the city to cede the fortress grounds to the municipal authorities, asked that the appearance of Montjuïc be improved. Two years later, the construction of an amusement park resulted in the destruction of 300

barracas and the rest were subsequently cleared to accommodate the expansion of the port [

15]. Despite these initiatives, and claims by politicians that the

barracas were fast becoming a thing of the past, several significant areas of shanty development remained in the city. Estimates vary, but according to the magazine

Ahora (cited in [

13]), almost 4800

barracas remained in the municipality of Barcelona in 1972 (

Table 1 and

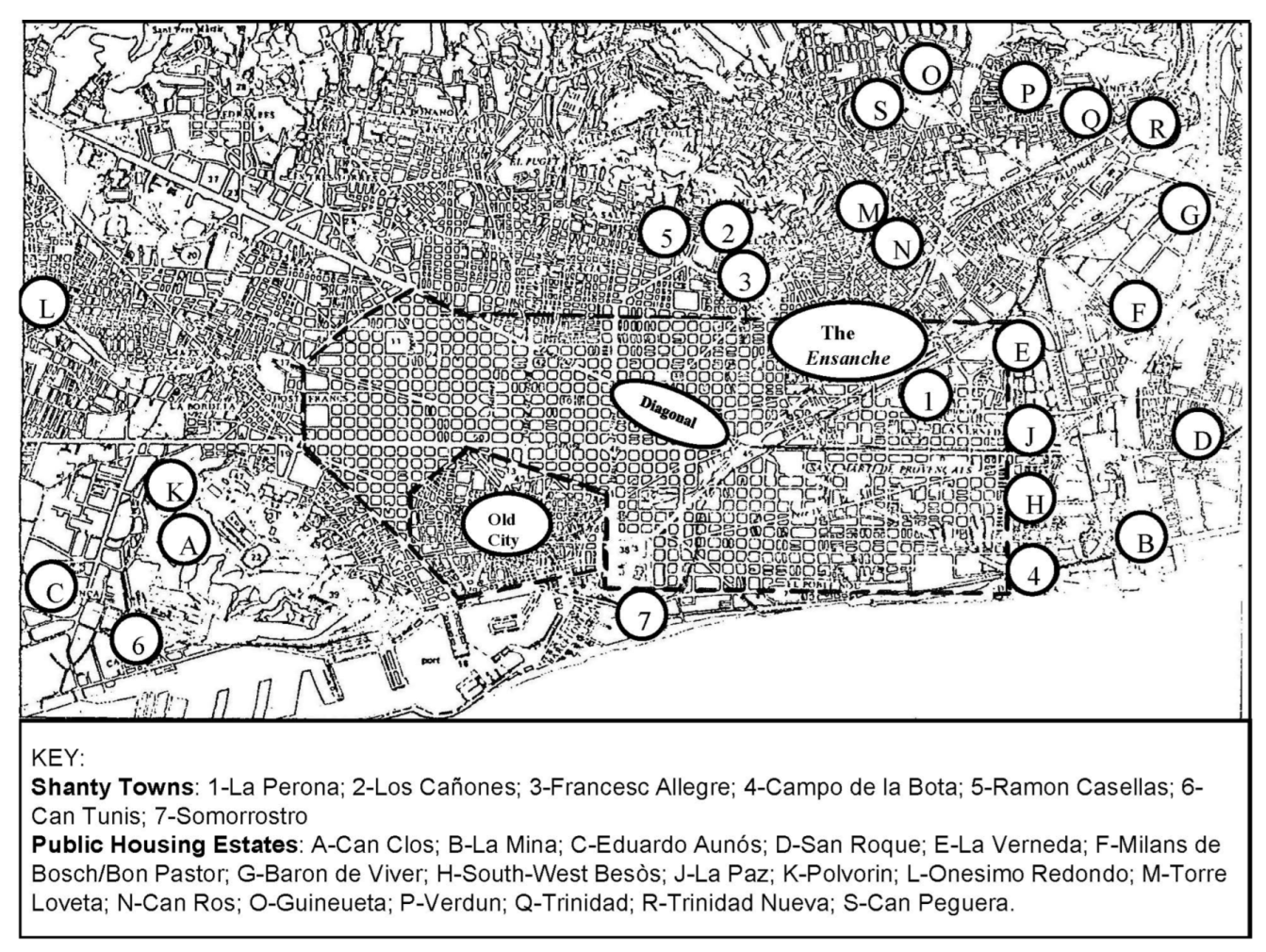

Figure 2).

In the late 1960s, the public housing authorities had stepped up their efforts to create new housing estates to re-house shanty dwellers. The

Obra Sindical del Hogar (OSH—a central State housing authority) constructed three

Unidades Vecinales de Absorcion (UVAs—Neighbourhood Overflow Estates) of 1500–2500 dwellings each in the adjoining municipalities of Prat (San Cosme), San Baudilio (Cinco Rosas), and Badalona (Pomar), built specifically to re-home residents from cleared shantytowns (

Table 2). The quality of these houses was so poor that 10 years later, one of these estates (San Cosme) was partly demolished and had to be rebuilt [

16]. The shantytowns in the city, however, did not disappear. Some were cleared but many remained on marginal hill land, alongside railway lines and on waste land, often in close proximity to industrial plants. Similarly, in the 1970s, the PMV constructed large housing estates at Canyelles and La Mina in the northern and eastern periphery of the city, specifically for the purpose of re-housing the

barraquistas.

As regards the plans and planning machinery of the day, the 1953

Plan Comarcal (sub-regional plan) provided the main official framework for planning and development in Barcelona. It was based on a “nuclear conception” of urban development in which growth of the different settlements in the sub-region was to be controlled and directed through adherence to a land zone classification system, stipulating land use and building densities for each classification. The plan was revised and extended in the Barcelona Metropolitan Area Plan in 1976. The fundamental objective was to ensure that the continued growth of the city could take place without being impeded by limitations on the availability of land, problems of congestion and service, and infrastructural deficits. At the same time, the plan accepted the impossibility of effecting radical change; the plan documentation noted that it “does not attempt to force drastic changes in the spontaneous development process” [

18] (p. 15), but rather attempted to guide and rationalise the location of different land uses and activities.

A new zoning system was introduced, in which many classifications were sufficiently wide-ranging to keep options open on the exact nature and timing of development. Of particular relevance was the introduction of zonings involving specified change of land use, e.g., new park areas, and urban renewal and rehabilitation zones, and the emphasis laid on the “Special Plan of Interior Reform” (

Plan Especial de Reforma Interior) (SPIR), as a means of bringing about this change. This was in accordance with the 1976 Land and Urban Planning Reform Act, which stipulated that the SPIR could be used for “the improvement of the urban and rural environment and the city suburbs” [

19] (article 22). The 1976 plan made provision for the drawing-up and approval of SPIRs “when modification of the existing building density, or provision of new service infrastructure, are considered necessary” [

20] (article 333).

The SPIR, along with its successor in subsequent legislation, the Urban Renewal Plan (Plan de Remodelación), provided a formal planning mechanism for the improvement or renewal of the shantytowns. However, as Busquets Grau [

21] (p. 59) noted in his study of marginal developments in the Barcelona periphery in the 1970s, shanty developments had grown up “completely outside the planning system”.

In terms of urban morphology, few of these shanty settlements were researched or documented in detail prior to their demolition. One of the few studies that approaches this is that by Busquets Grau [

22], who identified four types of access relative to existing roads (branching, double branching, tangential, and isolated), and four urban layouts (linear, dendritic, grid-like, and mesh-like) of various “marginal settlements” in the Barcelona periphery, including some of the shantytowns. At Los Cañones and Ramon Casellas (discussed below), for example, the layout is classified as tangential, as these settlements were built around tracks adjoining main roads at tangents. As regards the “building type” which Scheer [

23] defines as “a pattern, where we observe formal similarities between one building and another” (p. 171) or the “urban tissue”, which represents “patterns that involve a group of buildings, blocks, and streets that are formally similar” (p. 172), there was similarly little research done on these aspects of shanty development at the time.

Many of the photographs in this article illustrate the robustness of these shanty dwellings, built with brick, plaster, and wooden beams, often supporting corrugated tin roofs. Moreno Rivero [

24] (p. 168), in her study of the shantytowns on El Carmelo, described the construction process thus: “most of the

barracas were built with materials extracted from the terrain: stone and mud. The mud was kneaded with straw, introduced into some wooden molds, left to set for a day and became an ‘adobe’, which was substituted for brick, which had to be bought. The roofing was done mostly with wooden beams and a material called ‘cardboard leather’, similar to what now would be called an asphalt fabric, but of poorer quality”.

Other researchers have provided valuable insights into the lives of some of the shanty dwellers through interviews, focus groups, and personal recollections [

4,

15,

25], but that is not the intention here. Rather, this article uses photographs taken in the period just after Franco’s death to provide an impression of what life was like in some of the main remaining shantytowns of the day, and briefly charts their evolution and final demolition. This article also reflects upon the change in land use after the eradication of the shanties, and the process by which shanty dwellers were re-homed. The following section examines these issues as it tracks the origins and evolution of the main shanty developments considered in this study.

3. Photographic Histories—The Lost Shantytowns of Barcelona

This section discusses the origins and evolution of four of the remaining shantytowns in Barcelona in the mid-1970s, which were all demolished in the post-Franco era in the 1980s and early 1990s, prior to the Olympic Games in the city in 1992. La Perona was the largest remaining shanty development in the city in 1976, followed by Campo de la Bota and the combined settlements on the Tres Turons hill area, and it is these that are studied in

Section 3.1,

Section 3.2 and

Section 3.3. In

Section 3.4, the settlement of Ramon Casellas, just to the south of the Tres Turons, is studied, using photographs taken in 1978. This small settlement was more or less unique in the history of the shantytowns in Barcelona, in that replacement flats were constructed in situ and the residents themselves played a role in the plan-making and design process. Finally, in

Section 3.5, the history of the first four public housing estates in the city, dating from the late 1920s, is recorded. These buildings—often viewed as

barracas or

coreas because of their minimal dimensions and use of poor-quality materials in their construction—experienced similar fates to the true shanty areas, with only one of the estates surviving intact today.

3.1. La Perona

La Perona, located on the northeastern margin of the

ensanche (

Figure 2), was the largest remaining shanty development in Barcelona in the mid-1970s, and one of the last to disappear from the city in 1989. It grew up in the mid-1940s, and takes its name from the visit of the wife of the president of Argentina, María Eva Duarte de Perón (as in the film and musical “Evita”) to the area in 1947. The shantytown was located alongside the railway line on and around Ronda de Sant Martín, from the Puente de Espronceda past the old Puente de Trabajo (now relocated) along to the Riera de Horta (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

The shantytown expanded rapidly in the 1950s as immigrants, especially from Andalucía, came to the city in search of a better life. Water and electricity were installed by the local authorities, and some shanty dwellers purchased their plots from the railway workers who owned the land adjacent to the railway [

4].

By the mid-1960s, there were an estimated 200 shanties and 3000 shanty dwellers in La Perona [

26], and in the late 1960s, gypsy families came to increasingly dominate in the shanty development as previous dwellers moved out to apartments in housing estates built by the public housing authorities—the OSH and PMV—and gypsies from other areas of the city were relocated or moved of their own volition into La Perona (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

By 1972, there were an estimated 900 shanty dwellings in La Perona (

Table 1). The actions of the local authorities were two-fold—some improvement in services was provided, whilst at the same time the re-homing of some of the shanty dwellers was pursued. Camino et al. [

4] (p. 24) note, “the city’s intervention consisted in extending water services to the neighbourhood and paving some areas while simultaneously relocating some shanty dwelling families to apartments in La Mina and Pomar [PMV and OSH housing estates, respectively] from 1968 to 1974”. By the mid-1970s, a school for adults had been established (

Figure 7), and a nursery for children installed (

Figure 8). There was also a nearby bar, housed in an old farm building (

Figure 9).

Apart from the quality of houses constructed, and the deficiencies in services provision, other problems were in evidence across the history of La Perona. Attempts to re-house the shanty dwellers in peripheral estates brought protests from potential future neighbours, matched only by that of the present neighbours in San Martin. In August 1972, 40 women from the adjacent housing estate of La Verneda met in Plaza San Jaime in the city centre to discuss the matter with municipal authorities.

The Correo Catalan, a local newspaper, reported that in the opinion of the said women, the poor example set by the shanty dwellers and the consequent ill effects on the communal life in the area required urgent attention from the mayor. Several demonstrations and petitions ensued, and one barraca was set on fire. Attempts at re-housing the gypsy families were often further complicated by the fact that, in the majority of cases, they did not want to move anyway. For example, those resettled in the San Roque estate in Badalona soon left and returned to La Perona.

In the 1980s, Barcelona Council tried several plans and policies to relocate the shanty dwellers from La Perona. The construction of prefabricated single-family homes in the Pedrosa industrial estate, south of Montjuïc, was proposed but strongly opposed by local residents. As noted by Tatjer and Larrea [

25] (p. 264), “the fear of a possible degradation of the territory if the precarious population increased caused a series of neighbourhood reactions of rejection—that in some cases were expressed with a certain racist tone—in the face of some plans proposed by the Administration, without having been sufficiently negotiated with the citizens”. Some inhabitants accepted money in exchange for leaving their shanties and returning to their place of origin. Other families were moved piecemeal to new or second-hand public sector apartments across the city. In this manner, the residents of La Perona were moved out, and in June 1989 the final shanties were demolished, in preparation for the Olympic Games in 1992.

What of this land now, where La Perona once existed? In 2010, the first stone of a new station complex—to be called La Segrera—was laid by the president José Montilla, the Minister of Public Works, and the mayor of Barcelona, in the area where La Perona had stood. This has been described as “one of the largest railway works in modern history” [

27] (para. 7), an enormous multi-level new transport hub that will bring together high-speed inter-city trains, regional network trains, metro lines, and buses (

Figure 10). Only a small stretch of Ronda de San Martin remains, the majority of the old shantytown’s main street having been subsumed by the new railway development (

Figure 11).

This massive infrastructural project will also entail the development of “the largest urban garden in the city, …. nearly four linear kilometers and 40 hectares” [

27] (para. 2). There have been many delays—as there often are in such projects—but the station should be fully operational in 2024. This may provide a fitting and symbolic tribute to the shantytown known as La Perona, which stood on this ground alongside the old railway track for nearly 50 years, when green spaces and basic services were scarce and transport systems were of another age.

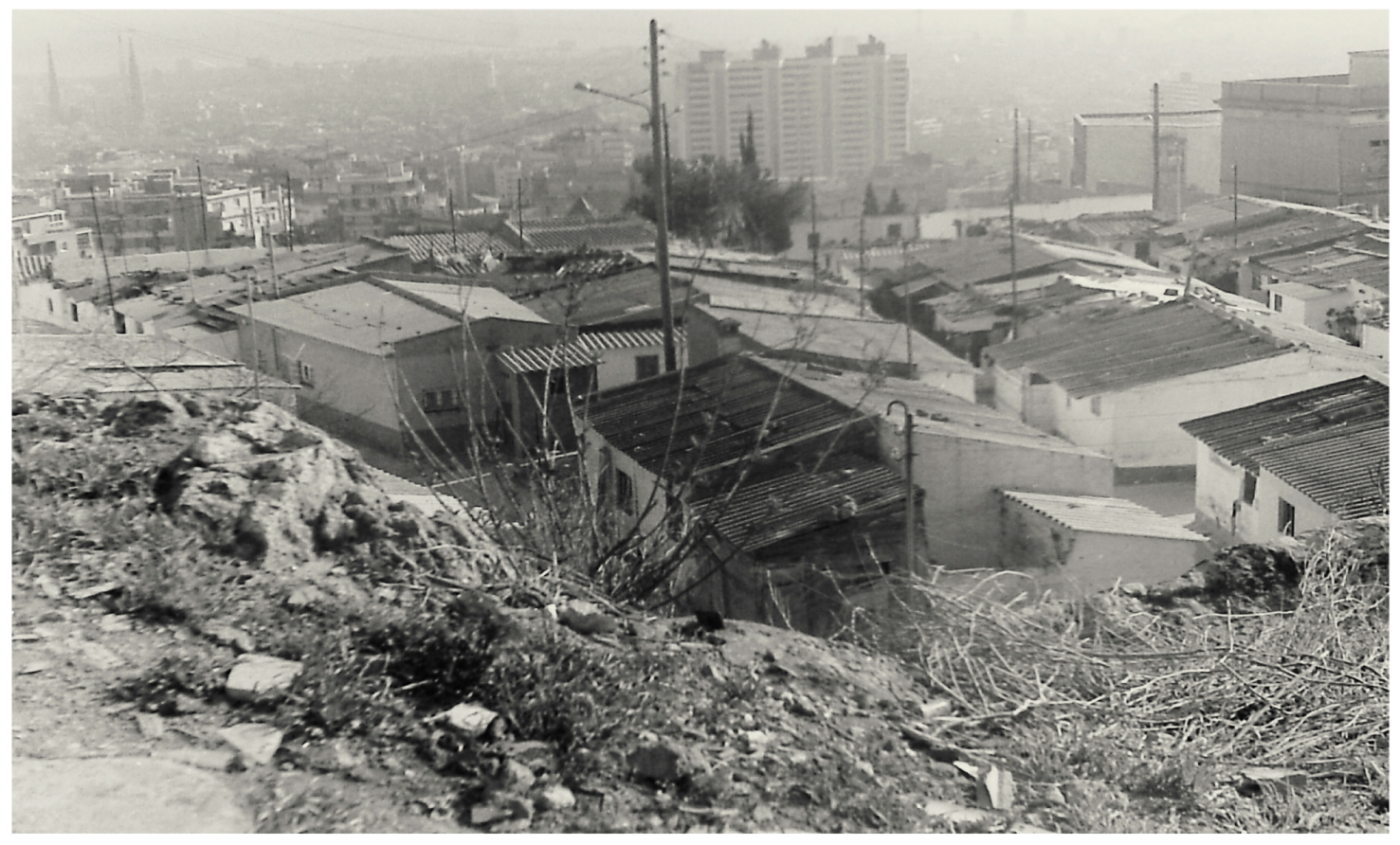

3.2. The Tres Turons: Los Cañones and Francesc Alegre

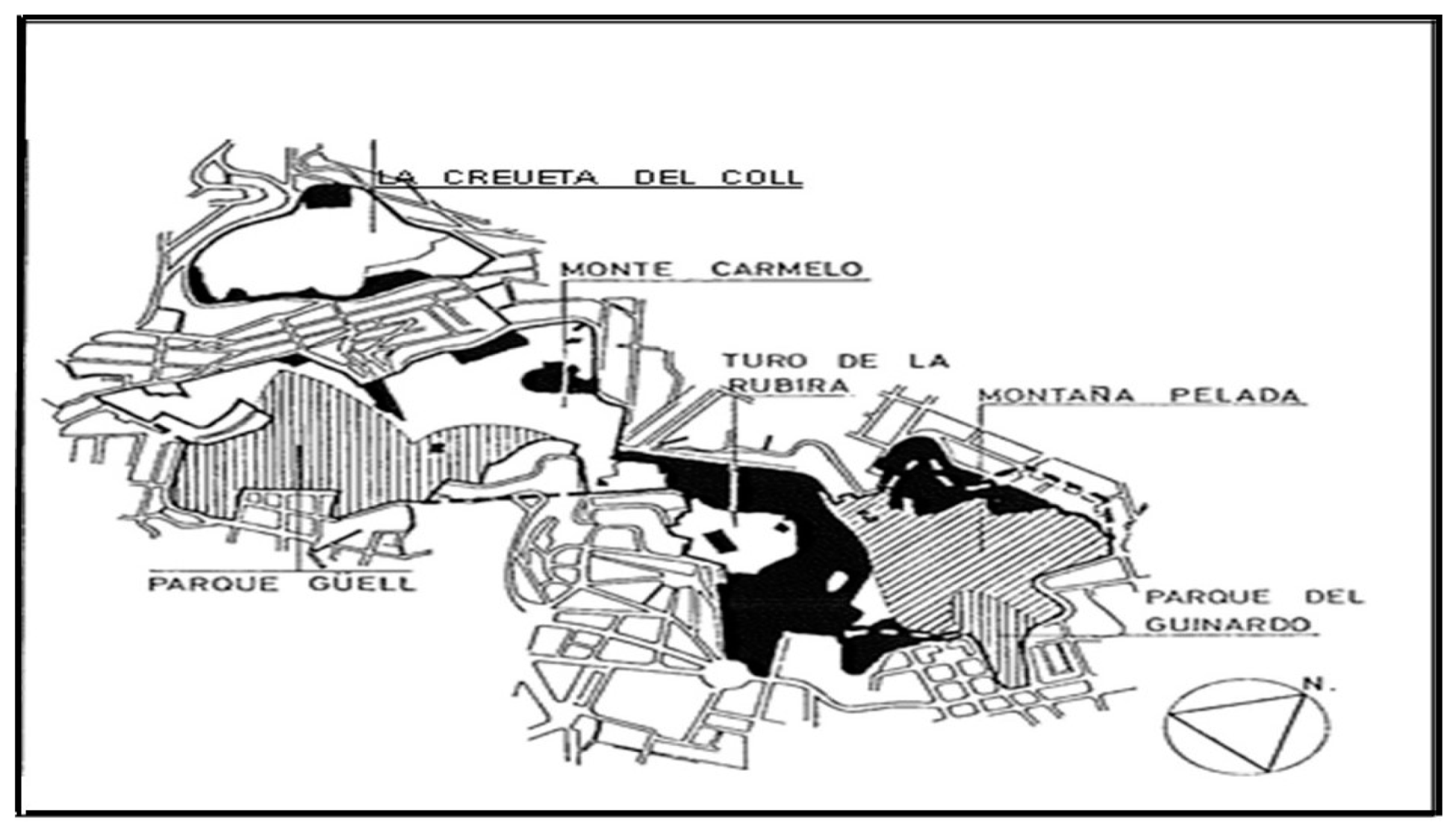

The Tres Turons (“Three Hills”) are in the northern suburbs of Barcelona. Over time, these hills have been used for recreation for the city as a whole, whilst also being the location for a number of shanty developments. Tarrago [

28], in his study of the growth of Barcelona, reported a mixed land use in 1971, with two areas of urban park (including the Parque Güell, designed by Antonio Gaudi), but also with significant areas of illegal developments—in the main shantytowns—across all three hill areas (

Figure 12).

The two main groups of shanties were spread across the central section of these hills, mainly on the Turo de la Rovira (

Rubira in Catalan). There were two main shanty settlements here—Los Cañones (also known as Marià Labèrnia) located on the northern hilltop, and Francesc Alegre, which was on the lower slopes in the southern part of the hill. It is these two shanty developments that are the main focus of this sub-section. The area as a whole is also sometimes referred to as El Carmelo or Monte Carmelo, on which livestock grazed in the mid-1970s (

Figure 13).

In the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), military installations had been sited on Monte Carmelo and Turo de la Rovira, and the first shanties that sprung up there in the mid-1940s used these abandoned installations for shelter. Hundreds of people used the old anti-aircraft bunkers to build the Los Cañones shantytown around the east–west running track known as Marià Labèrnia, at the top of the hill.

The Francesc Alegre settlement was further down the hill around, and just up from, the road of that name. In the sixties there were nearly six hundred makeshift homes, housing some three thousand people in these two settlements. Most of these shanty dwellers were from Andalucía and Extremadura in the south of Spain. Bou and Gimeno [

29], in their history of El Carmelo, draw attention to the harsh conditions—no water, electricity, sewage disposal, or other services—that prevailed in these shanties (

Figure 14 and

Figure 15).

More specifically, Moreno Rivero [

24] (p. 168), who had been a resident in this shantytown until 1972, and was a key figure in the resident protest movement there, highlighted the conditions in which residents had to live: “the

barracas were lit with oil lamps, candles, carbides...toilet needs were done in a bucket inside the hut or many times directly on the hillside. These wastes, along with the rest of the garbage, were emptied into a ditch that the residents themselves built as far away as possible from the

barracas, and when it was full, they covered it with earth, made another ditch, and so on. The water had to be fetched from the public fountain and, in some areas, it was neither close nor was there more than one, so they formed long queues to fill their jugs or buckets”.

In 1972, the El Carmelo Residents’ Association (

Asociación de Vecinos del Carmelo) was formed to press the local authorities for improved services: drinking water, schools and day care centres, a health centre, and improved public transportation. By the time of Franco’s death in 1975, most of the shanty dwellers had running water and electricity, and a garbage collection service had also been created. Following a meeting with the mayor of Barcelona, residents were given the option of relocating to apartments some three kilometres to the north in the public housing estate at Canyelles, constructed by the PMV. In 1977, 123 families—in the main from Francesc Alegre—were re-homed there [

30]. By 1990, the final 87 families who had remained in the Francesc Alegre shantytown were re-homed in the Can Carreras housing estate, adjacent to Canyelles, in La Guineueta. With the last remaining residents having been re-housed, most of the shanty dwellings were demolished.

Looking from behind Turo de la Rovira today, there is no obvious sign of the old shanties (

Figure 16), although over the other side of the hill, in Calle Marià Labèrnia, some of the old dwellings have been repurposed as viable homes (

Figure 17). Indeed, Camino et al. [

4] (p. 25), in their study of El Carmelo, observed that “one sometimes found a fragile boundary between shanty and self-build home”, this latter sometimes called a

corea, as noted above.

Ferrer [

10] (p. 74) has outlined how such buildings could be improved and legitimised: “areas of

coreas (also called marginal housing estates) were provided with urban access and services, to the point of having running water, electricity and lighting, and later came public transport. The fact of being located on plots previously acquired (or with some more or less formalized right over the land) allowed that, despite their urban planning illegality, they were not subject to demolition or targeted by public re-location policies, as happened with the

barracas, and were consolidated as urban neighbourhoods. Once legalized, they began a process of replacing the primitive

coreas with new houses with municipal licenses, adjusted to the conditions and parameters of municipal ordinances”. Nevertheless, the protest banner on the front of the house in

Figure 17 bears witness to the continuing fight by residents to keep their houses and avoid compulsory purchase and demolition.

In Francesc Alegre today, however, there is scant sign of the old shanty settlement, which has been replaced by trees and shrubbery on the borders of the Parque del Guinardó (

Figure 18). There were other smaller areas of illegal shanty development on the Tres Turons in the mid-seventies, as indicated in

Figure 12. On Monte Carmelo, to the west of Los Cañones, several rows of small shanties then existed, which have since been demolished or upgraded (

Figure 19 and

Figure 20).

Today, the old bunkers located at the top of Turó de la Rovira, at a height of over 260 m above sea level, provide one of the best panoramic viewpoints over the city of Barcelona. In the years after 2008, the site was excavated as an archaeological site, which according to Roca i Albert [

31] was “a gateway that legitimated shantytown dwellers to take up their rightful place in their city’s history”. The author noted that “the geometric regularities of Els Canons shanty town illustrated the technical skill of those who built the neighbourhood. The surfaces of the old tiled floors, reused and superbly organised, along with the remains of drains and other pipes, gave testimony to the desire to make the neighbourhood and the interior of the homes as pleasant as possible” (p. 31). In 2017, a plaque was unveiled at the site, now consisting of the anti-aircraft gun emplacements and the remains of the shanty dwellings, which are now managed by the History Museum of Barcelona (MUHBA), providing a fitting tribute to the former shanty dwellers of the Tres Turons.

3.3. Campo de la Bota

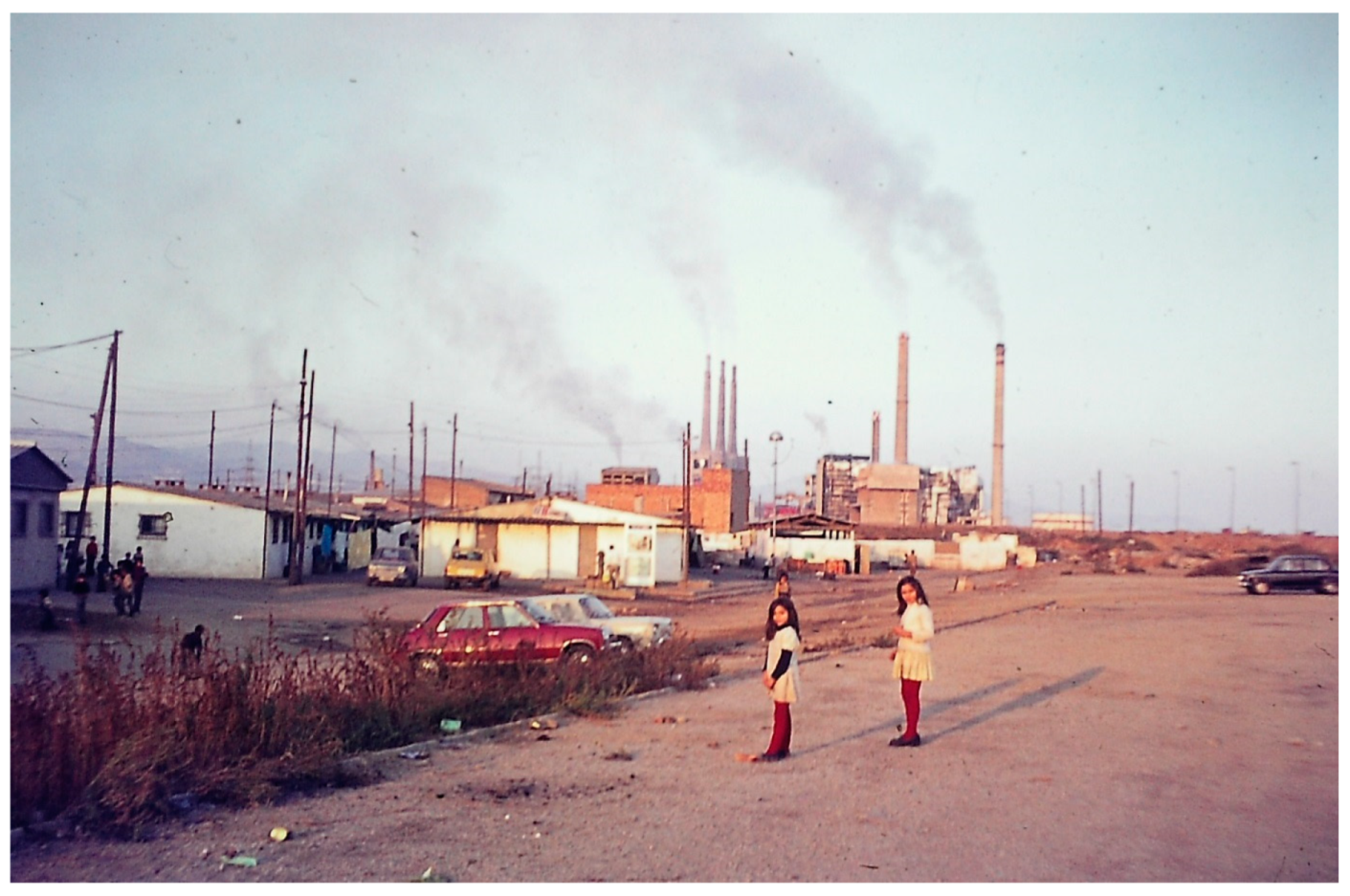

The Campo de la Bota shantytown was located to the east of Barcelona’s old city. It was close to the coast and adjacent to the municipal incineration and waste recycling plant, near the mouth of the river Besòs, in the San Adrián de Besòs municipality (

Figure 21).

This area of the city has something of a sinister past, as it was formerly a firing range in Napoleonic times, and was then taken over by the Spanish military. After the Spanish Civil War, it became known for its prison and execution ground, and it is estimated that 1700 people were executed here [

32]. A number of Nationalist sympathisers were also killed here by Anarchists during the Civil War. The area was abandoned by the Army in the 1950s.

The late 19th century witnessed the first shanty dwellings in the area, but it was in the 1920s that the area experienced significant growth, as more immigrants arrived in the city, including some from China, and from other Spanish regions, to work on the construction of the Barcelona International Exhibition of 1929. By the 1960s, a new influx of migrants in search of work from the south of Spain brought a further expansion of the shantytown, with some of the residents having been relocated there following the demolition of older shanty dwellings on the Somorrostro beach (in Barceloneta, near Barcelona’s old city) [

33]. In 1971, the Campo de la Bota shantytown comprised almost 700 dwellings, housing 3270 inhabitants [

34].

In the mid-1970s, the Barcelona Council embarked on a policy of transferring shanty dwellers from several parts of the city into the newly constructed La Mina public housing estate (built by the PMV), located nearby (

Figure 22). This involved “a forced concentration of persons of diverse provenance who shared a great precariousness and dependence on social supports, precisely when the economic crisis was causing mass unemployment among them” [

9] (p. 15).

Other authors have commented on the social problems this caused, not least for the education of children relocated in La Mina (

Figure 23). “The massive transfer of boys and girls from Campo de la Bota and other shantytowns to the La Mina schools was not easy at all; the mixture of so many diverse and unknown people, other styles, schoolchildren or children who had not been schooled, generated many problems” [

35] (p. 127). During the following years, the shanty dwellers were relocated in phases, and in 1989, the few remaining shanties were demolished.

Since then, the area has been redeveloped and has taken on a very different urban form. In 2004, the construction of the ultramodern

Forum de les Cultures covered up much of the Campo de la Bota site, and the area is now connected by a new urban motorway linking the city centre to the Besòs river valley and out to the east. There is a new Besòs Park area and marina adjacent to where the shantytown once was (

Figure 24).

The social problems on the La Mina estate have continued. Walker and Porraz [

36] (p. 22) noted that it “has acquired the reputation for being one of the most marginalized areas within the Barcelona Metropolitan Area”. An SPIR was drawn up and approved in 2002 and was largely completed by 2011 [

37]. The plan involved the partial demolition of oversized multi-family housing blocks, the opening of roads and public spaces, and the creation of new urban infrastructure in the area. Nevertheless, in 2020, the mayor of San Adriàn de Besòs warned of “the emergency situation in which this neighbourhood finds itself, converted into the ‘backyard’ of Barcelona and plagued by poverty and drugs” [

38] (para. 1).

The land use in this area of the city may have changed into something more in keeping with the global image of Barcelona as a major commercial centre and tourist destination (

Figure 25). However, those residents relocated in the La Mina estate may ruefully reflect on the quality of life in what has been termed “vertical shantyism” [

39] (para. 20), in comparison with their former lives in the Campo de la Bota shantytown forty years ago. According to Lopez Mirabet [

39], six percent of the residents remain illiterate and school absenteeism is at 40% of junior school pupils, and for secondary education, it rises to 77%. The report concludes, “we hope that in the coming years new projects will be launched to dignify a neighbourhood that wishes to look fearlessly into the future” [

39] (paras. 36/37).

3.4. Ramon Casellas

Ramon Casellas grew up in the mid-1940s and is often linked with the Tres Turons settlements of Los Cañones and Francesc Alegre discussed above in

Section 3.2. However, Ramon Casellas did not infringe on the park areas of the city, but rather was located in marginal, rocky land overlooking the city (

Figure 26 and

Figure 27), south of the hairpin bend in the Carretera del Carmel, which winds down from Monte Carmelo. This is clearly shown in the video on the “Shantytowns in Barcelona”, by Moncusi and Minguillon, available online [

40]. The shantytown was sometimes known as El Santo, and in the mid-1970s contained 135

barracas, in which about 650 people lived [

41].

Photographs of the shanty dwellings in 1978 indicate the varying quality of house construction, with many being well-kept and maintained, with electricity, washing facilities, pot plants, and shrubbery (

Figure 28 and

Figure 29). Nevertheless, the shanty dwellers, acting through their local residents’ association, pressed the local authorities for a wholescale re-homing of the community in replacement dwellings built in situ, to coincide with the phased demolition of the shanties.

The re-homing scheme for Ramon Casellas residents was one of the first schemes of redevelopment that actively involved the residents themselves in the planning process. In the late 1970s, at the dawn of the post-Franco era, new efforts were being made to resolve the shantytown problem in the city, with the active participation of affected inhabitants through a series of agreements between the Barcelona Council, the Ministry of Public Works and Urban Affairs, and the respective residents’ associations.

In these agreements, the associations’ elected architects worked with those of the Ministry in drawing up urban renewal schemes, with the residents themselves participating directly in the urban design process. The initial SPIR to replace the shanty dwellings in Ramon Casellas entailed the demolition of a small area of 80

barracas to be replaced by 122 housing units [

42]. However, after several administrative delays and plan amendments, 161 flats were completed in 1984 in the new Ramon Casellas apartment block, designed by Francesc Fonolà and his team, thereby relocating shanty dweller families within the same neighbourhood [

41].

The apartments became known as the “green flats” (

Figure 30), because of their all-green facades, and had some design elements in keeping with the shanty dwellings from which the residents had moved. Large common spaces and the sizes and typology of the floors, for example, were akin to those of the

barracas in which the residents had lived. The mini-estate was built around a square, with five separate buildings, three providing apartments for rent, and two with apartments for sale.

Photographs from 1978 help establish the location of the shantytown in relationship to today’s urban landscape. Taken from within the shanty development,

Figure 31 shows the adjacent block of the (then) modern flats, with the inset windows and stepped back, terraced balconies.

Figure 32 shows the same apartment block in recent years alongside part of the “green flats” structure, in which shanty residents were re-housed.

Looking southeast from the foothills of Monte Carmelo in 1976 (

Figure 33), Ramon Casellas can be seen in the centre of the photo spilling out from behind the seven-storey apartment block to the left. A recent aerial view from a similar position (

Figure 34) shows new blocks of flats occupying the land where the shantytown existed, one of which is the “green flats” complex in which shanty residents were re-homed.

In summary, the construction of the “green flats” (

Figure 35) and the re-homing of the shanty dwellers was the culmination of a successful collaboration between the residents’ association and the local authorities, notably Barcelona Council and the PMV (now more usually called

Patronat Municipal de l’Habitatge, its Catalan name). The history of this shantytown is of interest, not least because “a large number of its inhabitants succeeded in being relocated within the same neighborhood through local struggle and neighborhood associations” [

4] (p. 19). This represents a happy contrast with the fate of many of the shanty dwellers moved out of their shanty dwellings in other parts of the city to peripherally located poor-quality public housing estates.

3.5. Casas Baratas: The Early Public Housing Estates: Eduardo Aunós, Baron de Viver, Bon Pastor/Milans de Bosch, Can Peguera

This final sub-section looks at some publicly constructed dwellings that were of such minimal dimensions that they were sometimes viewed as coreas or were complemented by additional barraca developments. They were single-storey and often constructed specifically to re-house inhabitants of shanty areas that were being demolished. Ironically, the struggle of some of the residents to remain in, and upgrade, these early public housing estates parallels that of the shantytowns, with similarly mixed outcomes.

The funding and construction of these

casas baratas (cheap houses) was made possible by legislation approved in the reign of Alfonso XIII, before the proclamation of the second Spanish Republic in 1931. As noted above in

Section 3.3, there was a new wave of immigration into Barcelona in the 1920s, with migrants arriving from the south of Spain in search of work. They often found employment in the large infrastructure projects of the day, such as the construction of the city metro and the preparation of Montjuïc for the 1929 International Exhibition.

Within the framework of the second Cheap Houses Act (1921), the City Council created the

Patronato Municipal de la Vivienda (PMV) for Barcelona (referred to above), which commissioned house builders to construct four housing estates to re-home some of the shanty dwellers from the grounds to be cleared on Montjuïc, and to provide housing for some of the new immigrants arriving in the city. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, these four housing projects were undertaken at Eduardo Aunós (to the west of Montjuïc), Barón de Viver and Milans del Bosch (later renamed Bon Pastor), on the banks of the Besòs river to the east of Barcelona, and at Can Peguera, in the northeast corner of the city between El Turó de la Peira and La Guineueta (

Figure 2). At the time, they were in the underdeveloped city periphery and poorly connected with the city centre. Houses had an average floor space of about 50 square metres [

43].

The Eduardo Aunós estate was located between calle de Arnes and calle de Ulldecona in sight of the Olympic stadium on Montjuïc (

Figure 36). It was built in 1927 by the PMV and named after the then Minister of Works, Commerce, and Industry under the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera, who later became Minister of Justice under Franco. There were over 500 dwellings originally constructed, and in the 1970s, the majority were still occupied (

Figure 37). They were sometimes confused with the true shanty developments on Montjuïc at Can Tunis [

15] and other locations.

In the 1990s, the estate was demolished and replaced by six-storey apartment blocks (

Figure 38), there being 340 flats built in two phases. Residents were given the option of relocating to the new apartments. In 1993, the first 112 flats were constructed, followed by a delay, due to disagreements between the residents and the Barcelona City Council, but work restarted in 1996 on the rest of the apartments. In December 1998, the mayor of Barcelona officially opened the new look of the Eduardo Aunós neighbourhood [

44], with the Eduardo Aunós name remaining above a shop door (

Figure 39).

On the other side of Barcelona, in the 1920s, the PMV had acquired a large tract of land from the Marchioness of Castellbell on the banks of the Besòs river to construct a new estate named Baron de Viver [

45]. These 344 single-family homes were isolated between the Besòs River, the railway workshops, and the Besòs industrial estate, and many remained unoccupied until after the second world war, after which time they were used to house new waves of immigrants from Murcia and Andalusia [

46].

In the period 1956–1958, some of the dwellings were demolished and replaced by rapidly constructed blocks of flats to accommodate shanty dwellers re-housed from the Somorrostro shantytown on the Barceloneta beach. In the mid-1970s, some of the original dwellings remained (

Figure 40), but they were demolished in phases from the 1980s onwards and replaced by new apartment blocks. The first of these is best known for the square and the commercial area within the block, built in 1988 and designed by Emili Donato, an internationally known architect [

47].

Most of the new apartment blocks (

Figure 41) date from the 1990s. The initial housing blocks built in the 1960s to re-house the shanty dwellers from elsewhere in the city were of such poor quality that they were demolished. Nevertheless, there were still complaints about the quality of the most recently constructed apartments, concerning, for example, the availability of elevators and facilities for older residents or those with reduced mobility. The nature of the community has inevitably changed in recent decades. In his recent study of the history of the neighbourhood, Coloma [

48] (p. 40) pointed out “the destruction of the collective identity of the neighborhood linked to its past… creating a sensation for the residents of a suburban dormitory area”.

Further south on the banks of the Besòs river, the PMV built a larger estate of 784 single-family houses in 1929, called Milans del Bosch, later renamed Bon Pastor. In the Franco era, Bon Pastor grew as an industrial working-class area, known for its opposition to Franco’s military regime [

49]. In the 1980s and 1990s, the Barcelona Council offered tenants the option of renovating or enlarging their houses, in exchange for a significant increase in rent. However, at the end of the 1990s, the local administration adopted a new policy and approved an urban renewal plan (

Plan de Remodelación) which entailed the progressive demolition of the estate, and the construction of new blocks providing 1000 apartments, some of which were set aside for the relocation of Bon Pastor’s then current residents [

50].

The first 145 dwellings were demolished in 2007 and in October of the same year, the situation was brought to public attention by the violent eviction of a number of families who opposed the plan. Residents felt that the quality of the existing dwellings was adequate, and that demolition was inappropriate and unnecessary. In 2010, Bove et al. [

50] (p. 4), in their study of possible future options for the neighbourhood, noted “the central element in this dominant discourse is the alleged low quality of construction of the houses, which are constantly represented as obsolete or uninhabitable, at times playing on the assonance between the words ‘barates’ (‘cheap’) and ‘barraques’ (‘shanty houses’): the demolition of solid brick houses built 80 years ago is legitimised using the same discourse which was used to justify the clearing of shanties along the Spanish shoreline in the 80s”.

Nevertheless, demolition of the

casas baratas continued and more than 2000 residents were offered units in the new apartment blocks, with some residents demanding financial compensation or more favourable rental agreements in the new flats. In 2018, a few rows of housing from the original estate remained, boarded up and ready for demolition (

Figure 42). In his study of the plan and its implementation [

49], Pang concluded “since 2000, neighborhood residents have undergone extreme cultural disruption due to the demolition and reconstruction of their social housing complex” (p. 2) and that “while most residents managed to remain in the same place, the internal displacement impacted mutual aid networks and a different kind of gentrification and cultural disruption took shape” (p. 3).

The fourth

casas baratas estate, built in the late 1920s and early 1930s, was at Can Peguera on the slopes of Turó de la Peira hill, on land that had previously belonged to a farmhouse of that name. In 1929, the PMV purchased the old farmhouse and its land, and drew up plans to build four rows of terraced dwellings, each with a small garden. There were 200 houses of 58.2 square metres and 334 dwellings of 43 square metres. The 534-house estate was completed in 1931, and a further 116 dwellings were built in 1947. In contrast to the other three

casas baratas estates, Can Peguera (

Figure 43) has survived, maintaining its unique working-class character [

51].

However, this was not easily achieved and follows the successful protest movement by the residents to counter plans for the demolition of the estate, evidenced in the

Plan Comarcal of 1953 and Metropolitan Area Plan of 1976 [

52]. Largely as a result of local resident association activity, the provision of green spaces and other services in the estate has improved significantly in recent decades, and several phases of housing reforms have been completed, in which residents have had the option of deciding which improvements they wanted in their dwellings. Can Peguera remains as a unique testament to what was, and as a vision of what might have been, in the lost shantytowns of Barcelona.

4. Conclusions

This article has traced the evolution of some of Barcelona’s major shantytowns with a particular focus on the 1970s, using photographic illustrations from that decade. It has briefly recorded what happened to these shantytowns and gained some insights from secondary sources regarding the fate of the shanty dwellers. The article also looked at the short histories of four of the first public housing estates in the city, which were built to house immigrants and displaced shanty dwellers.

The article clearly has its limitations in that it is essentially a narrative synthesis with no primary interviews with the shanty dwellers or other protagonists in the evolution of the shantytowns. However, given the relative lack of detailed research on the shantytowns themselves, it is believed that the article makes a valid contribution in developing an awareness and deeper appreciation of this phase in Barcelona’s urban history.

The outcomes for the shanty dwellers varied considerably from location to location. In Campo de la Bota, many residents were forcibly re-homed in the nearby La Mina public housing estate, which has been plagued with a range of physical and social problems over several decades, despite a number of well-intentioned initiatives from local authorities and interest groups. The residents of La Perona fared little better, with many re-housed in the UVAs located outside of the Barcelona municipality in the outer periphery of the metropolitan area, where these poorly constructed estates often required major improvement or rebuilding programmes.

The inhabitants of Los Cañones and Francesc Alegre were more organised and the residents’ association there achieved some success in services provision and negotiating the re-homing process. Arguably most successful were the inhabitants of Ramon Casellas, where residents played a role in the plan-making and house design process that led to the funding and construction of the “green flats” in the terrain once occupied by the shantytown itself. The outcomes for the four casas baratas estates were similarly varied, with only one—Can Peguera—surviving today. The other three were demolished and replaced by apartment blocks with some of the residents being re-housed in situ, but their histories are similarly characterised by tension and discord between the residents and the local authorities.

The history of shantytowns in Barcelona can be seen as a result of shortcomings in housing policy and urban planning. Camino et al. [

4] (p. 27) concluded that “the increase in slums in Barcelona was brought about by waves of immigration, but the main cause of the shantytowns was determined by a lack of rational housing policy”, and that the shantytowns “grew up spontaneously outside of urban planning and which, in principle, except for some cases, were never recognized as part of this city–and perhaps this is why they disappeared”.

It is evident, nevertheless, that the shantytowns and their inhabitants played a significant role in the growth and development of the city. Roca i Albert [

53] observed that”these precarious urban settlements, however, were not a ‘burden on the city’, as often described. Rather, the shantytown dwellers played a significant role in the post-war economic recovery of the city, as a low-cost work force. They survived on low wages and were deprived of all social services” (p. 52).

Across Europe, although many of the shantytowns dating from the second half of the 20th century have similarly been demolished, shantytowns remain. With the new waves of migrants spreading across Europe, similar settlements are emerging again in a number of European cities as a housing “solution” for the urban poor in search of shelter. Outside Madrid, the Cañada Real shantytown is a linear 9-mile-long stretch of informal housing, the largest illegal settlement in a European city [

54]. In France, 439 shanty developments were recorded in 2021, housing 22,189 people, of which just over half were European Union nationals [

55]. And in Italy, in 2019, it was reported that “dozens have died in these makeshift settlements, in particular in the southern regions of Calabria, Puglia and Sicily. Most of them were very young immigrants” [

56] (paras. 1–2).

This provides another context within which to view the achievement of the Barcelona authorities in eradicating the shanties from in and around the city. Certainly, many of the re-homing initiatives were heavy-handed, insensitive to residents’ wishes and involved transfer to sub-standard tower blocks, particularly in the early re-homing projects in the pre-democratic era of the 1970s. Today, however, the absence of shantytowns in Barcelona sets the city apart from many of the other large urban conurbations in southern Europe.

Nevertheless, as academics and former shanty dwellers have pointed out, this era in Barcelona’s history should not be hidden or forgotten, but rather recognised as an important chapter in the evolution of the city’s growth, and the fight by its residents for improved services provision and replacement housing. Further studies could attempt to more precisely research the fate of the inhabitants of particular shantytowns as a whole, as well as trying to ascertain more detail regarding the physical aspects of the shantytowns. A review of the role of the urban planning system in Barcelona in allowing the existence, and then demolition, of these dwellings, as well as their reform and improvement, would also be of interest and value in an international context.

In 2008, the Barcelona History Museum held an exhibition entitled “Shanties—the informal city”, in which research on the shanties was presented. It noted that “the complete eradication of shantyism in the years preceding the Barcelona Summer Olympics has left no mark on the territory, but its story, which lives on in the memory of many one-time shanty dwellers, is still full of lights and shadows” [

9] (p. 3). A subsequent documentary [

57] (para. 4) noted, “Barcelona is swift to forget its shantytowns and its troubled past. Urban development and property speculation have wiped out the traces of many settlements. But they still live on in the memories of the slum dwellers, who want to see official commemoration of this episode in the city’s history... …to understand today’s city, the ‘other’ story must also be told”. This article has attempted to address this challenge by tracing the evolution of some of the city’s major shantytowns, based around photographs taken in the city almost 50 years ago.