Abstract

The effects of disinformation in the media and social networks have been extensively studied from the perspective of reception studies. However, the perception of this media phenomenon expressed by different types of audiences in distant geographic locations and with different media cultures has hardly been addressed by experts. This theoretical review study aims to analyze the relationship between the actual level of disinformation and the perception expressed by the audiences themselves. The results of the study reveal, firstly, that users of social networks and digital media do not perceive being surrounded by an excessively worrying volume of disinformation, a fact that contrasts with the data recorded, which are visibly higher. This situation reveals that the audience tends to normalize disinformation, which is intensively consumed on a daily basis and does not seem to worry the public in general terms, although some differences can be detected depending on variables such as gender, age or education. On the other hand, paradoxically, audiences visibly express rejection attitudes towards the channels that disseminate false information, with media outlets being the least trusted, despite recognizing that social networks are the place where more disinformation is generated and circulated at the same time.

1. Introduction

Disinformation is not a problem of recent emergence but is a matter that concerns the media in a larger measure as compared with other actors involved in digital communication. The proliferation of news that is fake, misleading or that includes erroneous or inaccurate data is already a problem in many information systems where media organizations compete with other communication companies whose function is not strictly informative but purely relational or related to entertainment. This is the case for social networks, where news is often created and disseminated by unknown agents at a much faster pace than in the media.

The publication of inaccurate, unverified or false information by some media outlets does not help to increase the level of trust placed in them by the public. The truth is that both misinformation and disinformation in the media are perceived by audiences as an attack on the right to receive truthful information, a right that is constitutionally guaranteed by the rule of law.

Disinformation, in particular, not only damages the reputation of the media that is accused of not being objective but also citizens’ lives, since the impact of fake news can be felt in many social decision-making processes.

In this sense, the consequences of disinformation have been analyzed in scientific research of a political nature [1,2,3,4] but also in the media [5,6,7] about the concept [8,9,10], the contents [11,12,13], the sources [14,15,16], the distribution channels [17,18,19] and the multiple strategies to fight against disinformation, among which media literacy stands out [20,21,22]. The effects of disinformation have also been discussed from the perspective of reception studies; however, there is a very small number of investigations that address in depth the problem of disinformation from the audience’s viewpoint through the so-called “perception studies”.

The experts agree on the fact that studies have hardly been undertaken on the way the public deals with fake news and what is the perception that they really experience [23,24]. As argued by Yang and Horning [25], the perception of disinformation that circulates, especially among users of social networks, is likely to influence their behavior and their attitudes towards the news published by the media. Thus, when the audience feels disinformed, negative feelings of manipulation and other reactions like media rejection and lack of interest in reading the news arise.

Tandoc, Lim and Ling [26] also carried out research on how the audience reacts when exposed to disinformation and the role the public plays in the dissemination of fake news, whether consciously or unconsciously. The authors suggest that disinformed people who believe fake news is true can contribute to the propagation of misleading information, which is the consequence of a wrong perception of the level of disinformation experienced by some individuals. Another relevant study is the one developed by Blanco-Herrero, Amores and Sánchez-Holgado [27] on the way disinformation is perceived by individuals depending on variables such as age, gender, education or social class, among others. The results show a lack of correlation between the disinformation perceived and experienced by some audience segments, like older individuals, whose perception of disinformation is higher and more negative than the one perceived by young people, or women, who proved to be more skeptical towards disinformation than men.

This bibliographical review study aims to complete the research carried out by experts in the past, summarizing and clarifying how the audience of different media outlets, social networks and other digital environments perceive disinformation. In this regard, the aim is to shed a more powerful light on the way disinformation impacts the audience of different media: to what degree does disinformation truly concern citizens, to what extent does it influence decision-making processes and in what way does it damage confidence in digital and new media. In that context, specific factors like political voting, audience decision-making on social and public issues and the public’s reaction to government or institutional disinforming news stories are analyzed.

The research questions of this work are in accordance with these goals and are listed as follows:

- Q1. Is there a correlation between audience disinformation perception and the public’s actual level of disinformation?

- Q2. Can audience disinformation perception influence on relevant decision-making processes?

- Q3. Concerning disinformation, are traditional media more distrusted than social networks?

The main objectives of this work are to know how disinformation really shapes the lives of people globally, to analyze the results of previous research on the problem of disinformation from a conceptual point of view and to draw useful conclusions for digital news consumers.

This study is relevant because, for the first time, a compilation of the main empirical contributions published to date that address the subject under study is carried out, an academic area little treated by experts, possibly due to the complexity of undertaking research work that involves multivariable analysis [28].

The results of the study reveal, in the first place, that digital media and social network users do not have the impression of being surrounded by an excessively worrying level of disinformation. This could be explained by an excess of confidence on the part of the users, who tend to perceive themselves as more capable of resisting the effects of disinformation than others, or by the habituation to a high level of disinformation, which is more and more accepted as normal. Consequently, the disinformation that is consumed on a daily basis does not seem to worry most of the public, although some differences can be seen depending on variables such as gender, age or education. Finally, the audience expresses a remarkable rejection towards fake news and traditional media, who are the least trusted, despite the fact that social networks are the place where the most disinformation is generated and circulated at the same time, according to the public.

2. Methods

The methodology of this study is qualitative and based on a bibliographical review of the scientific literature published on the subject under study over the last decade, focusing on the most recent research developed during the last five years. The analysis of this last period of time deals with the widespread use of social networks as new channels for the dissemination of journalistic information, and after noticing the boom that social networks such as YouTube and TikTok have experienced in the last five years as information channels. The analysis of this period of time is particularly relevant given that users of social networks increasingly turn to them for being informed on a daily basis, prioritizing them over news aggregators and media outlets.

The sample of works resulting from the bibliographical review conducted between the months of July and August 2023 was selected according to the following criteria: subject relevance, empirical nature of the investigations, geographic representation, multifactorial and demographic analysis and comparative analysis between media.

Around 50 research papers were finally selected, all of them closely related to the subject matter of this study, which focuses on audience perception of fake news and disinformation. The studies were developed from an empirical and not merely theoretical point of view in America, Europe, Asia and Africa on different gender, age, social class, level of education and political orientation audiences that get informed through different information channels (traditional media such as radio, television or digital media and social networks).

The results of the research were disseminated in international impact factor journals on communication publishing empirical research on reception studies and audience perception studies. These academic works were subsequently observed as units of analysis (investigations on reception studies and audience perception studies published during the last decade). The units of analysis were selected by means of automated documentary search tools according to the sample selection criteria mentioned above.

Comparative analysis was chosen as a method to collect and analyze data pursuant to the individualizing variant proposed by Tilly [29] in his comparative analysis typology. According to this procedure, a small number of cases are contrasted in order to capture all of their peculiarities. Taking into account the specific characteristics of this study, this is considered to be the most appropriate method to analyze the scarce number of works published by experts on the public’s perception of fake news and disinformation. The comparative analysis employs an illustrative-type strategy by which the cases and findings are thoroughly observed and explained.

Once the bibliographical sample was selected, the analysis of the data was performed, pointing out the differences and similarities of the results and identifying the trends that emerged from the examination of diverse media culture audiences located in distant geographic areas.

On the other hand, the analysis of the public’s media perception is addressed by taking as reference two closely related concepts: that of “disinformation” and that of “fake news”, and expressly excludes from the analysis allusions to “erroneous or inaccurate information” (misinformation). The first two notions serve a specific purpose such as the deliberate satisfaction of particular economic, political or ideological interests, while the second refers to incorrect information that is disseminated by mistake or ignorance, without intending to harm the interests of third parties or to obtain economic or political advantage.

The concept of disinformation employed in this study is based, therefore, on the intentional factor Allcott and Gentzkow [30] refer to in a way that is not only patent but also veiled, that leads to confusion [31] and that also uses formats similar to those used by the media [32]. The concept is in line with the one proposed by a large number of experts [26,32,33,34] and opposed to other conceptions of fake news not directly related to this notion.

Therefore, the concept of “fake news” that is taken into consideration is limited to information that is disseminated intentionally, excluding from it persuasive and humorous information included in some of the typologies reported by experts like Molina, Sundar, Le and Lee [35] (wrong or inaccurate information, persuasive information, citizen journalism), Tandok, Lim and Ling [26] (news satire, news parody, advertising and public relations), Wardle [36] (misinformation, meme, propaganda, satire) or Baptista and Gradim [10] (propaganda, parody news, advertising).

Therefore, this study focuses on news that deliberately includes false information with the intention of deceiving [37,38,39] and that, as occurs with disinformation, is disseminated through formats similar to journalistic ones [40,41]. The degree of falsehood that is propagated is high in all cases, excluding news that according to Nielsen and Graves [42] the audience simply does not believe, as is the case of sensationalist information or those that only report inaccurate facts.

The bibliographical review was used to analyze the state of the art of the subject matter at the present time when audiences seem to be more aware of the concept of disinformation and are more familiar with the presence of fake news in their everyday lives. The bibliographical review is presented as the most appropriate research technique to carry out the type of exploratory study that is undertaken on this occasion since it allows detecting the most relevant research trends and gaps that will arise during the analysis.

In order to avoid possible biases, the studies that have been analyzed take into consideration the perception of disinformation by audiences that belong to different media cultures. Among the selected sample of papers are works conducted on audiences of consolidated democracies, both in the United States [25] and in the countries of the European area [43]. Other studies have also been included on the perception of digital audiences in Asian [44] and African [28] countries governed by autocratic regimes where there is hardly any space for freedom of expression. How citizens of such social and cultural conditions perceive fake news and disinformation is an interesting issue, little or not at all explored from a comparative perspective, also inspiring when carrying out future research.

The results of the analysis are presented in accordance with the rules of descriptive statistics, a mathematical technique that obtains, organizes, presents and describes a given data set with the purpose of facilitating its understanding, through the use of tables and numerical or graphic measurements. It is an appropriate research technique to clearly describe the data recorded in this study and make them accessible to both a specialized and non-specialized audience. When necessary, the results of the analysis have been expressed in bar and column charts that describe data on significant variables from published research. The figures were adapted from the previous academic works available and play a necessary and clarifying role.

This bibliographical review study used research methods and techniques of a qualitative nature that are easily replicable in future studies that seek to update the state of the art and the results of the analysis put out in this research work.

3. Results

3.1. Levels of Disinformation Perceived by the Global Audience

Some academic works on how the public performs when exposed to fake news and disinformation have been published over recent years. Nevertheless, the results were not totally clear about the ability of the audience to detect fake news in diverse information contexts. The data recorded the actual performance of individuals from different countries, age, gender, level of education and social class, but did not include information on how the audience perceives disinformation and how this problem influences certain people’s attitudes. The fewer studies conducted by perception studies experts on this issue so far show little audience performance, even though significant differences were found when socioeconomic factors were analyzed.

3.1.1. Reception Studies Perspective

The moment is still close in time when a large group of followers of former US President Donald Trump stormed the Capitol on the basis of false information that pointed to alleged electoral fraud committed in the 2020 presidential elections [45]. It was the strong belief in that premise that prompted those followers to commit an illegal and violent act which resulted in the death of five people. This behavior, although extreme, is based, according to experts, on the massive dissemination of messages that are believed to be true. That community reaction usually results in activist-type behaviors [46] and has to do with the fact that users of social networks tend to share and disseminate information that they perceive as true, apart from fake news, which is normally highly widespread [46,47].

Knowing the skills of digital audiences when it comes to differentiating between true and false information is a subject on which there is considerable academic interest and, in this sense, some empirical research has been carried out with mixed results. On the one hand, individuals who participated in studies on false/true information reception in the past achieved an acceptable level of competence in general terms [47,48]. The results ranged from 51% [49] to 63% [50] regarding information published both on social networks and on the media [46]. In the European area, studies indicate that citizens are also capable of discerning between disinformation and misinformation [43]. However, the results reported by Nielsen and Graves [42] in the United States, United Kingdom, Finland, and Spain on the difficulties experienced by online audiences contradict previous findings. Figueira and Santos [51] also speak in this direction regarding the problems expressed by young people in Portugal when it comes to understanding different fake news content.

The differences recorded by experts are also felt in reception studies in regard to variables such as gender, age, political orientation or level of education. According to the works published by Guess, Nagler and Tucker [52] and Gómez-Calderón, Córdoba-Cabús and Lopez-Martín [53], young people are more affected by disinformation, as is the case with people of conservative ideology [52,53] and those with a lower level of education [54]. According to Casero-Ripollés, Doménech-Fabregat and Alonso-Muñoz [55], women would perceive disinformation less intensely, a fact also supported by the Thomson Reuters Foundation in a report on media consumption and audience perception in Georgia which asserts that women would be less aware of the presence of fake news in the media −56% of women compared to 70% of men- [56].

3.1.2. Perception Studies Perspective

The research results describe audience performance recorded in past reception studies, but there is hardly any research that addresses the perception of disinformation from the perspective of the audiences themselves. The few research studies carried out on this issue [57,58,59] came to the conclusion that the audience’s perception of disinformation and fake news is still low [43].

In 2018, when social networks began to be used more frequently as information channels, a study published in the European Union (Eurobarometer) described European citizens’ opinions on their ability to detect fake news [60]. At that time, most participants thought that they were capable of detecting disinformation published on social networks and the media. At present, when asked, the majority of those surveyed claim that they are well informed and are able to easily detect false information, although they consider that most individuals are not [24,25,61,62]. Recently, in the African continent, Gondwe [28] came to the conclusion that people with a higher level of education perceive themselves as more capable of detecting false information, while those less educated consider themselves less able to identify fake news. The results are similar to those obtained by Reuter, Hartwig, Kirchner and Schlegel [23] who found that the participants with university studies claimed to be able to detect fake news in 67% of the cases compared to 41% of the participants with secondary school education.

On the other hand, the latest research on perception studies indicates to what extent disinformation can shape citizens’ lives. According to Stabile, Grant, Purohit and Harris [63], disinformation can influence relevant decision-making processes such as voting, although this would be attenuated by the influence of variables such as age or political orientation. Thus, as revealed by Casero-Ripollés, Doménech-Fabregat and Alonso-Muñoz [55], citizens do not believe that disinformation impacts relevant decision-making, such as voting, or would make them change their opinion on issues of social relevance (particularly the age group from 50 to 64 years), although people with more academic training do think that disinformation can make them change their vote or their opinion on public talking points. This contrasts with the results of previous reception studies, since audience perception of disinformation is often inaccurate and inconsistent with reality, especially regarding issues debated in public [64] and the belief of fake news. In this sense, less educated people [55] and those who vote for right-wing political options are most likely to believe in fake news, as demonstrated in the 2016 United States presidential elections [7,30,65].

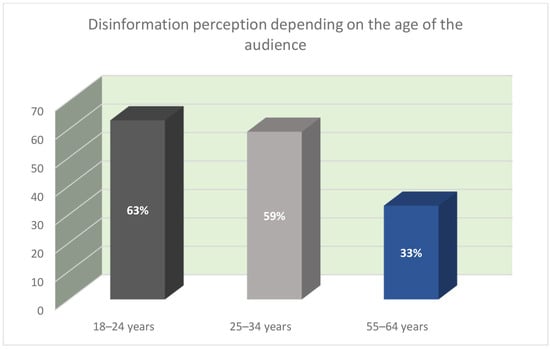

Other studies indicate that age influences the self-perception of the audience’s ability to detect fake news. The research conducted by Reuter, Hartwig, Kirchner and Schlegel [23] concluded that 63% of the respondents aged between 18 and 24 and 59% of the participants aged between 25 and 34 claimed to have detected fake news in the experiment, compared to 33% of participants aged 55–64 (Figure 1). These percentages are similar to the ones recorded by Hinsley [66] in a study with different age, academic background and political orientation participants. The youngest and best-educated individuals, as well as those who adhered to a more liberal political orientation, expressed greater confidence in detecting fake news than the rest. For its part, the conservative orientation seems to be the cause for a lower ability to identify fake news content, as held by Hinsley [66] and Casero-Ripollés, Doménech-Fabregat and Alonso-Muñoz [55], although other studies claim that political ideology is no longer an influential factor in the audience’s ability to detect fake news [44,67].

Figure 1.

Perception of the ability to detect fake news according to the public. Source: Data from [23].

Disinformation perception has also been analyzed in connection with traditional and new information channels. In general terms, research indicates that the audience perceives social networks as the channel that conveys a higher level of disinformation, although traditional media (digital media, print media, radio and television) are also described as disinforming channels. According to Blanco-Herrero, Amores and Sánchez-Holgado [27], television and the digital press—in that order—were perceived as more disinforming than radio and print media (also in that order), although the highest percentage was held by social networks. Young people expressed a greater distrust towards television, while older individuals were more concerned about fake news and disinformation channeled through social networks such as Facebook, LinkedIn or Telegram [27].

The audience disinformation perception circulating through social networks is in line with the results of previous research [30,68,69], although it is surprising that young people do not consider social networks as the more disinforming channel of all, taking into account that they use social networks much more intensively than adults. Possibly other studies that have analyzed the disinformation perceived and actually experienced by digital audiences of different age groups [70] could explain this. Nelson and Taneja [70] concluded that media literacy was a relevant factor in the detection of fake news by younger users of social networks, who also perceived themselves as more capable of identifying fake news than older individuals. Perhaps the extensive use of social networks by young people and their higher consumption of information, true and false, may have created that impression of self-confidence.

3.2. Level of Concern Expressed by the Audience Regarding Disinformation

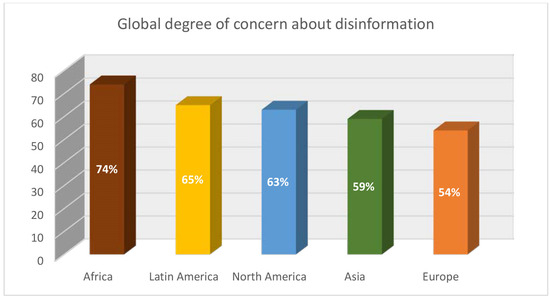

The level of disinformation concern experienced by audiences from different media cultures is not an issue that has been sufficiently studied up to now. Despite this, some research works have been published with disparate results depending on the population under study. There is a global trend of increased concern expressed by audiences in general terms, (58% of the global public), but the African continent (74%), Latin America (65%) and North America (63%) stand out for recording the higher levels of concern about the impact of disinformation. Asia (59%) and Europe (54%), by contrast, are the areas where audiences feel safest and least concerned about fake news being posted on social media and media outlets, according to a study by Newman, Fletcher, Schulz, Andi, Robertson and Nielsen [71] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Level of concern about disinformation expressed by global audiences. Source: Data from [71].

Research carried out by Gondwe [28] in Zambia revealed that, although a good number of participants expressed concern about the negative impact of disinformation, some respondents were of the opinion that fake news were entertaining. These respondents also thought that fake news provided an alternative perspective to the information published by the media, who were controlled by the government. Gondwe [28] found that, in the case of Zambia, the spread of fake news did not appear to be a particularly important issue for the audience, even when the information published turned out to be manifestly false.

This scant concern about disinformation was also recorded in the research conducted in Germany by Reuter, Hartwig, Kirchner and Schlegel [23] and according to which almost a quarter of the audience (24%) consider that fake news were annoying, but do not represent a real risk. Likewise, in Spain, Casero-Ripollés, Doménech-Fabregat and Alonso-Muñoz [55] found out that citizens, in general, do not have the feeling that disinformation has a significant influence in their daily lives, although they do acknowledge that fake news affects them. These results contrast with those recorded by the Pew Research Center in 2016 [72] in the United States and according to which the majority of the US population would be concerned about disinformation and fake news consumed on a daily basis, despite the fact that the level of concern would vary at the individual level [25].

In short, there seems to be a general consensus that disinformation poses a danger to the public, although the level of concern differs depending on the population under study. Disinformation can be more alarming in autocratic societies with authoritarian political regimes, although, as in the case of Zambia, the publication of fake news is almost welcomed by a sector of the population, who considers fake news less harmful than the news published by official media. Damaging democratic societies only seems to be a concern in rule of law countries such as Germany, where 78% of those surveyed were worried about the impact of disinformation on civil society [23], as well as in Spain, Argentina and Chile where fake news influence on social and political issues concern most of the population [73].

Concern about disinformation has been analyzed at a particular level by researchers from Asia, Latin America and Europe with dissimilar results on variables such as age, gender or political orientation. According to Chang [24], Taiwanese young people are the sector of the population most concerned about disinformation, which impact make them feel more vulnerable; however, the results reported by Rodríguez-Virgili, Serrano-Puche and Fernández [73] in Europe would indicate that older users are the most concerned by this issue. Women in Spain [73] and left-wing voters would be the segments of the population most concerned about disinformation and the spread of fake news in European (Spain), Latin American (Chile and Argentina) and Asian (Taiwan) countries [24,73]. The disparity in the results may possibly be explained by a variety of causes, such as sociocultural differences or the little attention that studies on disinformation perception have received with respect to demographic variables, as Hinsley says [66], which would justify future in-depth research on these and other relevant factors.

3.3. Level of Trust Placed in the Channels That Spread Disinformation

Citizens’ perception of being disinformed is reflected in the rejection of some sources of information, those that prove to be manifestly disinforming, but also, and above all, in the rejection of channels that disseminate false information, such as social networks and media outlets.

According to Xu, Zhou and Wang [74], the audience is more skeptical about social networks and more capable of identifying reliable sources of information when they consume news published in online media. However, young people who use social networks on a daily basis view them as an honest and spontaneous information channel when compared to traditional media, who are described as less objective [75].

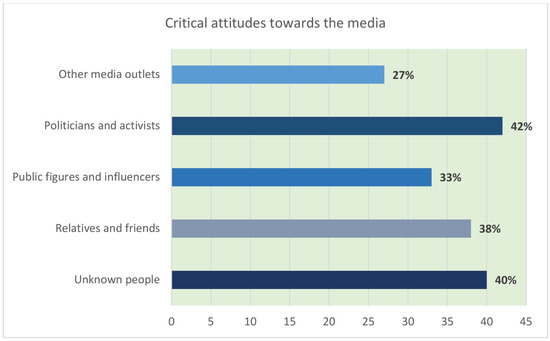

According to the doctrine [31,55], disinformation has a negative impact on the reputation of both social networks and the media, although there are notable differences across channels. In recent times, the public image of the media has been tarnished and not only due to its poor reporting but also because of the dismissive judgments expressed by public figures and some opinion leaders [76] (Figure 3). Today, the media are so discredited that, although the audience perceives social networks as highly disinforming [48], the public trusts them more than the media themselves. This transferring effect of distrust towards traditional media should be studied in depth, although the generalization of disinformation perception to all media [59], the presence of high and rising levels of disinformation in the media [77], the use of unverified sources of information from social networks by some media [78] and the abundance of highly politicized media outlets could explain this situation.

Figure 3.

Critical attitudes towards traditional media. Source: Data from [76].

The absence of rigorous fact-checking processes in well-known media outlets could be one of the causes for the highest level of media distrust expressed by the public. This conclusion follows from an interview with the fake news writer Tommaso Debenedetti on the Spanish TV station La Sexta [79]. Debenedetti, who since 2006 has been generating fake news and putting the media to the test, claims that “a journalist who does not verify a story is as guilty as the one who spreads a fake story”. Debenedetti, whose strategy consists of selling interviews of public figures that have never taken place to prestigious media outlets, argues that he is only playing a “critical game”. This game usually ends with a tweet announcing that the information that has been published and disseminated massively by the media is false.

The loss of confidence in the media has been observed for decades [80] and according to a doctrinal sector this could be partly based on the interplay of forces performed by political elites [81]. As stated by Baldacci, Buono and Gras [82], people massively exposed to certain ideas tend to trust more the opinions that come from particular sources of information even though these ones may not be credible, through the so-called “bandwagoning” effect. This is an effect also observed by Van Duyn and Collier [80] that results in a loss of confidence in the media and a decrease in the audience’s ability to identify information that is true. Kuklinski, Quirk, Jerit, Schwieder and Rich [83], Sides and Citrin [84] and Berinsky [85] also analyzed this situation, which could explain why people reject traditional media, including reputed media such as the British television channel BBC. According to a study published by Ofcom in 2022 [86], although most participants trusted the quality of the information published by the BBC, a significant percentage claimed that they distrust the TV network because they associate its news with the establishment.

In Europe, the countries that declare themselves most concerned about disinformation are Portugal, the United Kingdom and Spain, where 64% of the audience declare themselves concerned about the volume and intensity of fake news spreading [76]. Despite this, around a third of those surveyed are neutral regarding hoaxes and misleading news that circulate through the media and social networks, which suggests that some degree of acceptance exists and that disinformation is being more and more normalized by the public. The 2019 Eurobarometer already described a global landscape in which only 10% of the citizens of the 27 Member States of the European Union totally rely on the media [87]. Other citizens of the European area, such as Georgians, also expressed themselves in similar terms in a report published in 2021 [56] that collected the negative opinion of the public (52% of the participants) on the presence of propaganda and false information in all type of news and, especially, in those of a political nature.

As Romero-Rodríguez, Valle-Razo and Torres Toukoumidis [88] claim, the public’s confidence in the 20th-century media has been transferred to the new-millennium media. A few decades ago, news published in print media was considered credible by the public; nowadays, messages sent through social networks by a trusted contact are considered more credible, no matter whether they are true or false. On the other hand, the active role played by the public when creating and disseminating news in social networks enables higher levels of freedom unreachable in traditional media [5]. This can be positive or negative depending on the public’s intention, as social media users can contribute to spreading disinformation, either intentionally or unintentionally.

4. Conclusions

The abundance of studies on the reception of disinformation among audiences from different media cultures contrasts with the rare research conducted on the audience’s perception of this phenomenon. The bibliographical review that has been carried out on this occasion has sought to systematize the information available to date and to detect possible research gaps. The results of the analysis show a series of similarities between audiences from different geographical areas and also some differences that could be analyzed in future studies by experts.

Regarding the Q1 research question, similarities are observed at a global level regarding the audience’s actual ability to detect false information, which, in addition, is consistent with the level of disinformation perceived according to research published in countries of Europe, North America, Latin America, Africa and Asia. Although there are differences based on demographic variables such as age, education or the political orientation of the audience. Thus, older citizens, with a higher level of academic training and with a left-wing political orientation would be perceived as the most capable of facing the impact of disinformation. Although these results are likely to vary depending on the political and media culture of some countries with authoritarian regimes in areas such as the African continent or Asia.

In general terms, it is observed that the actual level of disinformation endured by the audience is somewhat higher than the perceived one, especially by young people (between 37% and 49% of actual disinformation compared to 34% of perceived disinformation), which means that the public believe they are less uninformed than they really are. Possibly, due to the difficulty in admitting that someone cannot tell the difference between true and false information or because some individuals are not able to perceive disinformation at all. This outcome could be worrying in democratic terms because many important decisions, such as voting, will be taken on the basis of weak or false information.

On the other hand, and with respect to the Q2 research question, the results indicate that global audiences do not seem to be overly concerned about the volume of disinformation they consume on a daily basis, both in democratic and autocratic regimes, and that is spread through different information channels. The public does not seem to be fully aware of the negative impact of fake news -global percentages range between 54% and 74% of the world population-, otherwise disinformation circulating through digital media and social networks has not had as big an impact on decision-making processes as assumed. On the one hand, the results are consistent with the low level of disinformation perceived by the audience, but, on the other hand, the results would be questioning the conclusions of previous empirical research that warn about the negative impact of disinformation and, above all, on relevant decision-making processes. The development of more in-depth research on the perception of disinformation that addresses the analysis of variables such as age, gender, education or the level of exposure to fake news would shed more light on this aspect.

In connection with the Q3 research question, the results also indicate that the audience’s perception of social networks and the high level of disinformation disseminated through that channel has been normalized because, despite the fact that users are aware of the danger that social networks represent, they tend to be more distrustful of traditional media. The reasons may be cultural, ideological or of another nature, either way, this situation encourages a careful reflection of how the media can restore their reputation and regain the audience’s confidence. New informative practices should be implemented, practices that would be more credible and objective, strategies able to withstand the competition of social networks and that make the media look more appealing, especially before new audiences like digital natives who primarily get informed through social networks instead of traditional media.

The bibliographical review work carried out on this occasion brings new knowledge on how disinformation is perceived and experienced by global audiences, revealing an existing gap between reception and perception studies with respect to disinformation consumption by different types of public. The study can be replicated at a local or regional level in order to obtain more detailed and comparative results that expand the scarce existing knowledge on how the audience perceives disinformation and fake news spreading at this time. Future research could focus on the analysis of sociocultural factors as well as media habits of audiences from diverse political cultures and the impact of disinformation perceived by the public in other decision-making processes other than voting, among others.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created in this study. All the data included or mentioned in this review are available and can be consulted on the references section of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Nyhan, B.; Reifler, J. When Corrections Fail: The Persistence of Political Misperceptions. Political Behav. 2010, 32, 303–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeks, B.E.; Garrett, R.K. Electoral Consequences of Political Rumors: Motivated Reasoning, Candidate Rumors, and Vote Choice during the 2008 U.S. Presidential Election. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 2014, 26, 401–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunther, R.; Beck, P.A.; Nisbet, E.C. “Fake news” and the defection of 2012 Obama voters in the 2016 presidential election. Elect. Stud. 2019, 61, 102030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantarella, M.; Fraccaroli, N.; Volpe, R. Does fake news affect voting behaviour? Res. Policy 2023, 52, 104628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejias, U.A.; Vokuev, N.E. Disinformation and the media: The case of Russia and Ukraine. Media Cult. Soc. 2017, 39, 1027–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freelon, D.; Wells, C. Disinformation as Political Communication. Political Commun. 2020, 37, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, S.; Tenove, C. Disinformation as a Threat to Deliberative Democracy. Political Res. Q. 2020, 74, 703–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, K.; Wang, S.; Lee, D.; Liu, H. Mining Disinformation and Fake News: Concepts, Methods, and Recent Advancements. In Disinformation, Misinformation and Fake News in Social Media; Lecture Notes in Social Networks; Shu, K., Wang, S., Lee, D., Liu, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapantai, E.; Christopoulou, A.; Berberidis, C.; Peristeras, V. A systematic literature review on disinformation: Toward a unified taxonomical framework. New Media Soc. 2021, 23, 1301–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, J.P.; Gradim, A. A Working Definition of Fake News. Encyclopedia 2022, 2, 632–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, K.; Wang, S.; Liu, H. Beyond News Contents: The Role of Social Context for Fake News Detection. In Proceedings of the Twelfth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining (WSDM’19), Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 11–15 February 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 312–320. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.; Qi, P.; Sheng, Q.; Yang, T.; Guo, J.; Li, J. Exploring the Role of Visual Content in Fake News Detection. In Disinformation, Misinformation and Fake News in Social Media; Lecture Notes in Social Networks; Shu, K., Wang, S., Lee, D., Liu, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosińska, K.A. Disinformation in Poland: Thematic classification based on content analysis of fake news from 2019. Cyberpsychology J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2022, 15, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, H.; Roy, P.; Saba-Sadiya, S.; Tang, J. Multi-Source Multi-Class Fake News Detection. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Santa Fe, NM, USA, 20–26 August 2018; pp. 1546–1557. [Google Scholar]

- Pedriza, S.B. Sources, Channels and Strategies of Disinformation in the 2020 US Election: Social Networks, Traditional Media and Political Candidates. J. Media 2021, 2, 605–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybyla, P.; Borkowski, P.; Kaczynski, K. Countering Disinformation by Finding Reliable Sources: A Citation-Based Approach. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Padua, Italy, 18–23 July 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rodny-Gumede, Y. Fake it till you make it: The role, impact and consequences of fake news. In Perspectives on Political Communication in Africa; Mutsvairo, B., Karam, B., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 203–219. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman, H.; Madrid-Morales, D. An Exploratory Study of “Fake News” and Media Trust in Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa. Afr. J. Stud. 2019, 40, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, H. Fake news from Africa: Panics, politics and paradigms. Journalism 2020, 21, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, D. Teaching media in a ‘post-truth’ age: Fake news, media bias and the challenge for media/digital literacy education. Cult. Educ. 2019, 31, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygren, T.; Frau-Meigs, D.; Corbu, N.; Santoveña-Casal, S. Teachers’ views on disinformation and media literacy supported by a tool designed for professional fact-checkers: Perspectives from France, Romania, Spain and Sweden. SN Soc. Sci. 2022, 2, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoro-Montarroso, A.; Cantón-Correa, J.; Rosso, P.; Chulvi, B.; Panizo-Lledot, Á.; Huertas-Tato, J.; Calvo-Figueras, B.; Rementeria, M.J.; Gómez-Romero, J. Fighting disinformation with artificial intelligence: Fundamentals, advances and challenges. Prof. Inf. 2023, 32, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, C.; Hartwig, K.; Kirchner, J.; Schlegel, N. Fake News Perception in Germany: A Representative Study of People’s Attitudes and Approaches to Counteract Disinformation. In Tagungsband WI 2019. Human Practice. Digital Ecologies. Our Future, Proceedings of the 14. Internationale Tagung Wirtschaftsinformatik (WI 2019), Siegen, Germany, 23–27 February 2019; Asssociation for Information Systems: Darmstadt, Germany, 2019; pp. 1069–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C. Fake News: Audience Perceptions and Concerted Coping Strategies. Digit. J. 2021, 9, 636–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Horning, M. Reluctant to Share: How Third Person Perceptions of Fake News Discourage News Readers from Sharing “Real News” on Social Media. Soc. Media Soc. 2020, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandoc, E.C., Jr.; Lim, Z.W.; Ling, R. Defining “Fake News”: A Typology of Scholarly Definitions. Digit. J. 2017, 6, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Herrero, D.; Amores, J.J.; Sánchez-Holgado, P. Citizen Perceptions of Fake News in Spain: Socioeconomic, Demographic, and Ideological Differences. Publications 2021, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondwe, G. Audience Perception of Fake News in Zambia: Examining the Relationship between Media Literacy and News Believability. 2023; pp. 1–16. Available online: https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/ggondwezunda/files/audience_perception_of_fake_news2.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Tilly, C. Big Structures, Large Processes, Huge Comparisons; Russel Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Allcott, H.; Gentzkow, M. Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election. J. Econ. Perspect. 2017, 31, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakidou, M.; Morani, M.; Cushion, S.; Hughes, C. Audience understandings of disinformation: Navigating news media through a prism of pragmatic scepticism. Journalism 2022, 24, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazer, D.M.J.; Baum, M.A.; Benkler, Y.; Berinsky, A.J.; Greenhill, K.M.; Menczer, F.; Metzger, M.J.; Nyhan, B.; Pennycook, G.; Rothschild, D.; et al. The science of fake news. Science 2018, 359, 1094–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaster, R.; Lanius, D. Speaking of Fake News. In The Epistemology of Fake News; Bernecker, S., Flowerree, A.K., Grundmann, T., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; pp. 19–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfert, A. Fake News: A Definition. Informal Log. 2018, 38, 84–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, M.D.; Sundar, S.S.; Le, T.; Lee, D. “Fake News” Is Not Simply False Information: A Concept Explication and Taxonomy of Online Content. Am. Behav. Sci. 2019, 65, 180–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, C. Information Disorder: The Essential Glossary. Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy. 2018. Available online: https://firstdraftnews.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/infoDisorder_glossary.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Klein, D.; Wueller, J. Fake news: A legal perspective. J. Internet Law 2017, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bakir, V.; McStay, A. Fake News and The Economy of Emotions: Problems, causes, solutions. Digit. J. 2018, 6, 154–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egelhofer, J.L.; Lecheler, S. Fake news as a two-dimensional phenomenon: A framework and research agenda. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 2019, 43, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rini, R. Fake News and Partisan Epistemology. Kennedy Inst. Ethics J. 2017, 27, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallis, D.; Mathiesen, K. Fake news is counterfeit news. Inq. Interdiscip. J. Philos. 2019, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, R.K.; Graves, L. “News You Don’t Believe”: Audience Perspectives on Fake News. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Report. 2017. Available online: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/our-research/news-you-dont-believe-audience-perspectives-fake-news (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Hameleers, M.; Brosius, A.; Marquart, F.; Goldberg, A.C.; van Elsas, E.; de Vreese, C.H. Mistake or Manipulation? Conceptualizing Perceived Mis- and Disinformation among News Consumers in 10 European Countries. Commun. Res. 2021, 49, 919–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, S.J. Motivated Fake News Perception: The Impact of News Sources and Policy Support on Audiences’ Assessment of News Fakeness. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2020, 98, 1059–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; Rand, D.G. Research note: Examining false beliefs about voter fraud in the wake of the 2020 Presidential Election. Harv. Kennedy Sch. Misinf. Rev. 2021, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T’Serstevens, F.; Piccillo, G.; Grigoriev, A. Fake news zealots: Effect of perception of news on online sharing behavior. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 859534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennycook, G.; Epstein, Z.; Mosleh, M.; Arechar, A.A.; Eckles, D.; Rand, D.G. Shifting attention to accuracy can reduce misinformation online. Nature 2021, 592, 590–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FECYT. Desinformación Científica en España (Informe de Resultados). Fundación Española Para la Ciencia y Tecnología. 2022. Available online: https://www.fecyt.es/es/publicacion/desinformacion-cientifica-en-espana (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Paskin, D. Real or fake news: Who knows? J. Soc. Media Soc. 2018, 7, 252–273. [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Jang, S.M.; Mortensen, T.; Liu, J. Does Media Literacy Help Identification of Fake News? Information Literacy Helps, but Other Literacies Don’t. Am. Behav. Sci. 2019, 65, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, J.; Santos, S. Percepción de las noticias falsas en universitarios de Portugal: Análisis de su consumo y actitudes. Prof. Inf. 2019, 28, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guess, A.; Nagler, J.; Tucker, J. Less than you think: Prevalence and predictors of fake news dissemination on Facebook. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, B.G.; Córdoba-Cabús, A.; López-Martín, Á. Las fake news y su percepción por parte de los jóvenes españoles: El influjo de los factores sociodemográficos. Doxa Comun. Rev. Interdiscip. Estud. Comun. Cienc. Soc. 2022, 36, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; Rand, D.G. Fighting misinformation on social media using crowdsourced judgments of news source quality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 2521–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casero-Ripollés, A.; Doménech-Fabregat, H.; Alonso-Muñoz, L. Percepciones de la ciudadanía española ante la desinformación en tiempos de la COVID-19: Efectos y mecanismos de lucha contra las noticias falsas. ICONO 14. Rev. Cient. Comun. Tecnol. Emerg. 2023, 21, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson Reuters Foundation. Georgia: Media Consumption and Audience Perceptions Research. 2021. Available online: https://epim.trust.org/application/velocity/_newgen/assets/TRFGeorgiaReport_ENG.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Gualda, E.; Rúas, J. Conspiracy theories, credibility and trust in information. Commun. Soc. 2019, 32, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masip, P.; Suau, J.; Ruiz-Caballero, C. Percepciones sobre medios de comunicación y desinformación: Ideología y polarización en el sistema mediático español. Prof. Inf. 2020, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardèvol-Abreu, A. Influence of Fake News Exposure on Perceived Media Bias: The Moderating Role of Party Identity. Int. J. Commun. 2022, 16, 4115–4136. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. Eurobarometer Report, Fake News and Disinformation Online, Flash Eurobarometer 464, April 2018. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/at-your-service/es/beheard/eurobarometer?year=2018&type=eng.aac.eurobarometer.filters.allTypes (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Buturoiu, R.; Durach, F.; Udrea, G.; Corbu, N. Third-person Perception and Its Predictors in the Age of Facebook. J. Media Res. 2017, 10, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbu, N.; Oprea, D.-A.; Negrea-Busuioc, E.; Radu, L. ‘They can’t fool me, but they can fool the others!’ Third person effect and fake news detection. Eur. J. Commun. 2020, 35, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabile, B.; Grant, A.; Purohit, H.; Harris, K. Sex, Lies, and Stereotypes: Gendered Implications of Fake News for Women in Politics. Public Integr. 2019, 21, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, B. The Perils of Perception: Why We’re Wrong about Nearly Everything; Atlantic Books: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Grinberg, N.; Joseph, K.; Friedland, L.; Swire-Thompson, B.; Lazer, D. Fake news on Twitter during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Science 2019, 363, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinsley, A. Cued up: How audience demographics influence reliance on news cues, confirmation bias and confidence in identifying misinformation. ISOJ J. 2021, 11, 89–109. [Google Scholar]

- Pennycook, G.; Rand, D.G. The Psychology of Fake News. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2021, 25, 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardle, C.; Derakhshan, H. Information Disorder. Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policymaking; Council of Europe Report; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, G. Politics of Fake News: How WhatsApp Became a Potent Propaganda Tool in India. Media Watch 2017, 9, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.L.; Taneja, H. The small, disloyal fake news audience: The role of audience availability in fake news consumption. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 3720–3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, N.; Fletcher, R.; Schulz, A.; Andı, S.; Robertson, C.T.; Nielsen, R.K. Digital News Report 10th Edition. Reuters Institute. 2021. Available online: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2021 (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Pew Research Center. Many Americans Believe Fake News Is Sowing Confusion. 2016. Available online: http://www.journalism.org/2016/12/15/many-americans-believe-fake-news-issowing-confusion/ (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Rodríguez-Virgili, J.; Serrano-Puche, J.; Fernández, C.B. Digital Disinformation and Preventive Actions: Perceptions of Users from Argentina, Chile, and Spain. Media Commun. 2021, 9, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhou, D.; Wang, W. Being my own gatekeeper, how I tell the fake and the real—Fake news perception between typologies and sources. Inf. Process. Manag. 2023, 60, 103228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadlington, L.; Harkin, L.J.; Kuss, D.; Newman, K.; Ryding, F.C. Perceptions of fake news, misinformation, and disinformation amid the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative exploration. Psychol. Popul. Media 2023, 12, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, N.; Fletcher, R.; Eddy, K.; Robertson, C.T.; Nielsen, R. Digital News Report 2023. Reuters Institute. 2023. Available online: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2023-06/Digital_News_Report_2023.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Valenzuela, S.; Halpern, D.; Araneda, F. A Downward Spiral? A Panel Study of Misinformation and Media Trust in Chile. Int. J. Press. 2022, 27, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varona-Aramburu, D.; Sánchez-Muñoz, G. Las redes sociales como fuentes de información periodística: Motivos para la desconfianza entre los periodistas españoles. Prof. Inf. 2016, 25, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Sexta. Tommaso Debenedetti Interview. La Roca, Broadcasted on 14 May 2023. 2023. Available online: https://n9.cl/9qe63 (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Van Duyn, E.; Collier, J. Priming and Fake News: The Effects of Elite Discourse on Evaluations of News Media. Mass Commun. Soc. 2018, 22, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheufele, D.; Krause, N. Science audiences, misinformation, and fake news. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 7662–7669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldacci, E.; Buono, D.; Gras, F. Fake News and Information Asymmetries: Data as Public Good (Conference). London. 2017. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319503207_Fake_News_and_Information_Asymmetries_Data_as_Public_Good (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Kuklinski, J.H.; Quirk, P.J.; Jerit, J.; Schwieder, D.; Rich, R.F. Misinformation and the Currency of Democratic Citizenship. J. Politics 2000, 62, 790–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sides, J.; Citrin, J. European Opinion About Immigration: The Role of Identities, Interests and Information. Br. J. Political Sci. 2007, 37, 477–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berinsky, A.J. In Time of War: Understanding American Public Opinion from World War II to Iraq; Chicago Studies in American Politics; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ofcom. Drivers of Perceptions of Due Impartiality: The BBC and the Wider News Landscape; Qualitative Research Report; Jigsaw Research: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. Eurobarometer Report. Standard Eurobarometer 92—Autumn 2019. 2019. Available online: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2255 (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Romero-Rodríguez, L.M.; Valle-Razo, A.; Torres-Toukoumidis, A. Hacia una Construcción Conceptual de las Fake News: Epistemologías y Tipologías de las Nuevas Formas de Desinformación. In Poder y Medios en las Sociedades del Siglo XXI; Pérez-Serrano, M.J., Alcolea-Díaz, G., Nogales-Bocio, A.I., Eds.; Egregius Ediciones: Seville, Spain, 2018; pp. 259–273. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).