1. Introduction

The financial system, which fundamentally serves to accumulate and distribute monetary assets, operates based on two models: the Continental and the Anglo-American model. Irrespective of the models, recent decades have witnessed a significant growth potential within the system, driven by a convergence of technological advancements and the benefits of accelerated globalization [

1]. However, in the first decade of the twenty-first century, the first indicators of an economic downturn began to emerge in the form of market turbulences. Consequently, market participants found themselves impacted by the emerging global pandemic amidst an economic recession caused by slowing productivity growth, attributed not solely to the 2007–2008 global economic and financial crisis but also to underlying structural economic issues, as noted by the International Monetary (IMF) [

2].

The early twenty-first century was characterized by constant technological progress. The economic growth in the second decade was challenged by a new threat in the form of the onset of a global pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The disease called COVID-19 brought about turbulence in the world market, which affected all market actors, has few parallels in modern history. The pandemic has caused significant disruption to health systems, triggering widespread panic and uncertainty around the world. The combination of uncertainty and panic lead to the disruption of transactional market mechanisms, which resulted in the gradual onset of the Pandemic Economic Crisis. This type of crisis has been seen several times in modern history. However, given its scale, the currently emerging crisis differs from previous ones in many respects. The presented study brings a systematic insight into the issue of Pandemic economic crises in the context of financial systems. The factors that created the conditions for strong growth at the beginning of the economic cycle have thus been exhausted by the slowdown in the pace of technological convergence and the ageing of the workforce. In conjunction with the saturation of world trade, these factors pose a significant threat to the system. In the years preceding the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the growth was marked by the postponement of serious problems, which in turn created the environment for the emergence of a recession [

3].

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, which emerged at the beginning of 2020, has affected all market players. Its rapid spread led to extensive restrictions, concerning primarily mobility, which ultimately disrupted traditional logistics flows. Studies on this issue suggest that the global economy has been severely affected by the combined effect of adverse factors culminating at the time of the onset of the global pandemic. In the light of these adverse factors, there is still a great deal of uncertainty regarding the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic where the first ones could be noticed as early as in the first year of the pandemic, mainly in the form of rising inflation and disrupted logistics chains [

4]. Despite these indicators, the impact of the pandemic on the world economy was greatly underestimated in its beginnings, leading to weaker stimulus measures [

5]. Changes in the global economy occurred mainly at the level of consumption structure. The changes in consumer buying behavior gradually evolved into a global crisis that damaged the economy and depleted the health sector. It can be assumed that the disruption of the whole ecosystem will lead to socio-economic changes [

6]. In this context, the present study brings the topic of pandemic economic crises closer to a wider professional public. At the same time, the authors aim to summarize the findings for further research on the issue.

2. Theoretical Background

The term economic crisis refers to a broader downturn in economic activity, including factors such as a decrease in GDP, increased unemployment, and a weakening in consumer spending. In contrast, financial crisis is characterized by a disruption to financial markets and institutions. This leads to liquidity shortages and credit crunches [

7]. The term economic and financial crisis appears quite frequently in the available literature [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Considering the global dimension of this term, one of the first crises that corresponded to the above definition was the Tulip Economic Crisis, also known as “Tulip Mania”, which was a speculative bubble in the 17th century in Dutch Republic, characterized by an irrational frenzy for tulip bulbs, leading to exorbitant prices and eventual market collapse [

8]. Later on, a crisis called the Panic of 1873 occurred during the period of industrialization. The panic began with the collapse of the stock market in Europe. Investors began to sell off the investments they had in American projects, particularly in railways. However, it brought nearly two decades of stagflation, a period known as the Long Depression [

12], or the Great Depression in the United States. It was not until the events of 1929 and 1930 that new standards were set. The main triggers of this historical landmark were a combination of adverse historical events such as wars and major fires, as well as economic events, such as the demonetization of silver in the Anglo-Saxon world. However, the term economic and financial crisis itself is much broader, as it refers not only to finance, but also crises affecting services, manufacturing, the commercial sector, etc. [

13].

Musílek et al. [

14] defined a sovereign financial crisis as a situation when a country is unable to repay its loan obligations. These are problems with financial management of the state. As a result, a financial crisis can be the starting point of a currency crisis or a credit crunch. Both cases, however, are associated with a significant deterioration in most financial indicators, which is manifested by liquidity shortage in the financial system, widespread insolvency of financial institutions, an increase in the volatility of rates of return on financial instruments, a significant decline in the value of financial and non-financial assets, and a substantial reduction in the scale of the allocation of savings in the financial system. According to Lisý et al. [

15], financial crisis is a situation in the financial market where asset prices fall due to investors’ loss of confidence in domestic assets. As a result, the investors then seek to invest in financial assets abroad.

Oztek and Ocal [

16] describe the traditional division of financial crises into two types: (i) crises that occur during cyclical economic development, and (ii) crises that are caused by factors of a predominantly exogenous nature. Those crises are associated with factors of the external environment, such as politics and finance.

Regardless of the specific nature of crises, financial markets bear the risk of turbulence caused by crises in a significantly negative way. Nevertheless, the emergence and evolution of crises can be mitigated by financial policy instruments. According to Goodell [

17], however, such fluctuations can have a long-lasting impact on the overall economic wealth. During such fluctuations, an initial sign effect on financial markets can be observed in the form of more than 25% loss in their value.

Since the outbreak of the pandemic, many economists have focused mainly on stock markets when analyzing its effects. In many studies published on stock markets, authors have used a variety of methods to collect and analyze research material [

18], focusing mainly on data relating to the performance of individual companies, unemployment rates, gross domestic product and overall data relating to the dynamics of pandemics.

The present study analyzes the issue of economic crises, particularly in the context of pandemics that have occurred in the last century. Emphasis is put on the area of financial markets, which are perceived as important indicators of turbulence in the global economy. The source of the data is the academic literature as well as scholarly studies published on the issue. For the purposes of the study, mostly secondary data were used. The main scientific methods used in the study are analysis and synthesis, with decomposition and abstraction constituting an integral methodological support apparatus.

The main outcome of this study is a brief summary of research findings in this area and a thorough examination of the interrelationships between pandemics and financial crises, with their significant relationships coming to the fore.

3. Discussion on the Effects of Pandemics on Global Economy

In modern history, there have been several pandemics that have affected the world economy. The first pandemic in this period was caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus, known as the Spanish flu (1918–1919). According to available data, it infected one third of the world’s population and killed 50 million people [

19]. The pandemic was followed by a global economic recession with a 6% decline in GDP per capita [

20]. During this period, a widespread recession broke out in developed countries. The recession was slowed down by the stock market, which developed significantly during this period, especially in the United States. Most of this development was due to the investment of spare funds in the shares of the companies that formed the backbone of the national economy at the time. However, this gave rise to market anomalies which, at the end of the third decade of the twentieth century, led to the crash on the New York Stock Exchange (Black Thursday in 1929) in the same period when the Great Depression began [

21]. In the following decades, several health situations occurred but did not reach the level of a global pandemic.

Other major pandemics of the twentieth century included repetitive influenza epidemics. The Asian flu, which occurred in China in 1957 and resulted in two million deaths, meant a significant drop in GDP growth in economic response, including a global contraction of around 2%. The slowdown in economic growth was the result of a variety of factors, including disruptions in production, trade and consumption as a result of the pandemic. In particular, different sectors experienced mixed impacts. Sectors closely linked to international trade and travel, such as transport and tourism, have been particularly hard hit. Indeed, fears about the economic impact of the flu have led people to become risk averse, affecting investment decisions and contributing to the downturn in markets [

22]. Next, in 1968, the Hong Kong flu pandemic killed twice as many people as the previous pandemic and caused a global economic decline of 0.3–0.5%. Production disruptions, labor shortages and changes in consumer behavior are factors that could have contributed to the downturn. Different sectors were affected to different degrees. Sectors such as healthcare and pharmaceuticals may have seen increased activity, while sectors dependent on face-to-face contact, such as tourism and hospitality, may have suffered. In 1977, Russia experienced an influenza A pandemic, also known as the H1N1 pandemic, which had a noticeable impact on both stock markets and global GDP, resulting in a decline in global GDP of around 0.1–0.2%. Investor sentiment during the Russian flu pandemic may have played a key role in shaping market dynamics. The pandemics of the twentieth century culminated in 1997 with the first of three epidemics of avian influenza (H5N1), which also affected economies and caused a sharp decline in sectors such as tourism, leading to estimated global losses of billions of dollars. Avian influenza (H5N1) recurred in China between 2003 and 2018 [

23]. A SARS epidemic caused by SARS-CoV or SARS-CoV-1 was reported in 2002–2003 in China. In terms of the impact of the epidemic on the economy, the SARS epidemic in 2003 led to a reduction of two percentage points in China’s gross domestic product growth in the second quarter of 2003, from 11.1% in the first quarter to 9.1% in the second quarter. In terms of the impact of the epidemic on the economy, the SARS epidemic in 2003 reduced China’s GDP growth by two percentage points in the second quarter of 2003, from 11.1% in the first quarter to 9.1% in the second quarter [

24]. Businesses in the tourism and hospitality sector experienced a significant decline. Airlines, hotels and travel agencies faced reduced demand as people refrained from travelling due to fears of contracting the virus. Airlines, both domestic and international, experienced a sharp decline in passenger numbers. Hotels and accommodation providers experienced a decline in bookings as tourists cancelled or postponed their travel plans. [

24].

The H1N1pdm09 virus, commonly referred to as swine flu, first emerged in the 1970s. It did not cause serious problems on a global scale until around four decades later. The World Health Organization declared swine flu a pandemic in 2009. Nevertheless, due to the prevailing global financial crisis at that time, its impact on the financial market cannot be precisely measured. According to Stiglitz [

25], the global financial crisis in 2009 was triggered by a combination of several adverse factors that had their roots in the financial crisis of 2007–2008. This period is referred to as the Great Recession, dating from 2007 to 2009. As such, the crisis erupted in the USA, and the author sees the causes of the crisis mainly in the application of the neoliberal model of economic governance, which established market law as the sole means of controlling and regulating the economy. In the course of 2009, the effects of the global economic crisis were widely felt across all areas of the real economy. In particular, the world market experienced a decline in demand for products and services, and the uncertainty caused by the crisis in the financial markets froze the economic processes that determine supply. This, in turn, resulted in a global recession and induced significant macroeconomic imbalances in various countries such as Ukraine, Argentina, Russia, and Mexico [

26]. In economic terms, the market lost approximately 2.2% of the global GDP in 2009.

The Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa in 2014 had a significant impact on the global economy, causing damage in excess of thirty billion US dollars [

27]. Remarkably, however, the epidemic did not disrupt the stability of stock markets and the momentum of the major indices. Despite the lack of direct impact on financial markets, the Ebola epidemic led to a decline in foreign direct investment (FDI) in the affected regions, as investors adopted a cautious stance in response to the heightened uncertainty and associated risks. Several sectors, including agriculture, mining and services, bore the brunt of the epidemic’s impact. Agricultural production fell as labor shortages and movement restrictions disrupted farming activities. The countries most affected by the Ebola epidemic, Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea, experienced economic contraction. Disruptions to trade, production and labor markets contributed to an overall decline in economic activity [

28].

In 2015, another health threat in the form of Zika fever was recorded, caused by the virus of the same name. The disease spread across both American continents and the Pacific region. Although the epidemic was declared over in February 2016, at the same time, the World Health Organization declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern concerning clusters of microcephaly cases and neurological disorders in areas affected by the Zika virus [

29]. According to Peixoto et al. [

30], the Zika virus epidemic had a severe economic impact on the affected countries, worsening socioeconomic inequalities and perpetuating cycles of poverty and disease. In particular, the 2015–2016 Zika virus outbreak has had significant health consequences, particularly in relation to birth defects. There has been no documented widespread impact on the global economy comparable to major global events such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

SARS-CoV-2, formerly 2019-nCoV virus, started the new coronavirus pandemic at the turn of 2019 and 2020. In modern history, this was the first pandemic, which, due to its scope, represented both a global health and economic threat. In its beginnings, the financial markets almost immediately recorded the turbulence that the spreading pandemic was causing to fragile economies across the world market. In February 2020, China’s Shanghai Stock Exchange Composite index fell by more than 8%. At the same time, all Western stock markets rose and opened at daily all-time highs. The situation changed quickly with the pandemic posing a global threat to the stock market and making the market development difficult to predict. Salisu and Vo [

31] used a database of twenty national markets most affected by the pandemic and regions with the highest mortality during the pandemic. The authors investigated whether online health reports can be used to predict stock returns. The results show that the model that includes the health news index outperforms the benchmark model of historical averages, indicating the importance of health news search as a good predictor of stock returns.

Sharif et al. [

32] investigated the time-frequency interactions between oil prices, pandemics, financial instability, geopolitical tensions, and the stock market in the United States using a Granger causality test based on the wavelet model and wavelet coherence. Conversely, the authors faced limitations arising from the dependence on a particular timeframe of the data, potential sensitivity to the chosen analytical methods, and the assumption of causal relationships based on correlations. Ma, Rogers, and Zhou [

33] compared the global economic and financial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic with those of past epidemics and pandemics, such as SARS in 2017, H1N1 in 2009, MERS in 2012, Ebola in 2014, and Zika in 2016, as described by Jamison et al. [

34]. A common feature is the apparent economic crisis, which was characterized by an immediate decline in real GDP growth in all affected countries, followed by a relatively rapid recovery. Nevertheless, economic performance remains below pre-shock levels for several following years. This pattern is consistent with the aftermath of other health crises, which often show a negative economic impact followed by a gradual recovery, albeit with varying degrees and durations of economic downturn. Studies by Ali, Alman, and Rizvi [

35]; Dawson [

36]; and Iyke [

37] confirms the negative impact that COVID-19 had on exchange rate returns, corporate values, and stock market volatility. In parallel with these findings, observations of macroeconomic instability arising from the COVID-19 pandemic in different financial scenarios appears in the literature and in relevant scholarly papers. Goodell [

17] discusses the economic and societal implications of COVID-19 and finds parallels with previous crises. The behavior of financial markets during the COVID-19 crisis is studied in detail by Conlon and McGee [

38] and Corbet, Larkin and Lucey [

39], with a focus on examining the correlation with gold and cryptocurrency prices. Their research consistently provides evidence that Bitcoin does not function as a security or safe haven during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the findings from these studies are potentially subject to limitations attributable to the extraordinary nature of the crisis. The dynamic correlations identified during this exceptional timeframe do not necessarily translate to all market conditions, requiring caution in extrapolating these results as a solid basis for incorporating Bitcoin into a mainstream portfolio.

Yarovaya, Matkovskyy, and Jalan [

40] analyzed herding behavior in cryptocurrency markets during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the authors, herding behavior remains conditional on bull or bear market days but does not intensify during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, Azimli [

41] used quantile regression to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the level and form of financial dependence in the United States. Based on this, the author identified a higher degree of dependence in the financial sector with a higher percentage of market returns and portfolios. Other studies analyze stock market volatility in emerging markets in the Middle East, South America, and Central and Eastern Europe [

42,

43]. Other studies focus mainly on the pandemic and its impact on tourism stocks (beach stocks) listed on the Chinese stock exchange, i.e., the country where the pandemic started [

44]. The global pandemic has caused considerable market volatility, with almost all economic sectors experiencing deviations from their benchmarks. With the spread of the pandemic to other countries (Italy, Spain, Germany, USA), the quotations of the main indices of almost all countries fell at the end of February 2020 [

45]. According to the World Bank [

46], the COVID-19 recession saw the fastest and steepest decline in consensus growth forecasts of any global recession since 1990. Despite a relatively unfavorable forecast for 2020, which predicted the worst recession since the Great Depression, the economy is slowly recovering as the pandemic recedes. In the January 2023 update of the World Economic Outlook, the International Monetary Fund [

47] forecasts global growth to fall to 2.9% in 2023. The 2023 forecast is 0.2 percentage points higher than the October 2022 World Economic Outlook forecast, but below the historical average of 3.8%. Rising interest rates continue to weigh on economic activity. Global inflation is expected to fall to 6.6% in 2023 and 4.3% in 2024, which is still above the pre-pandemic levels. In line with this, Grigoriev, Pavlushina, and Muzychenko [

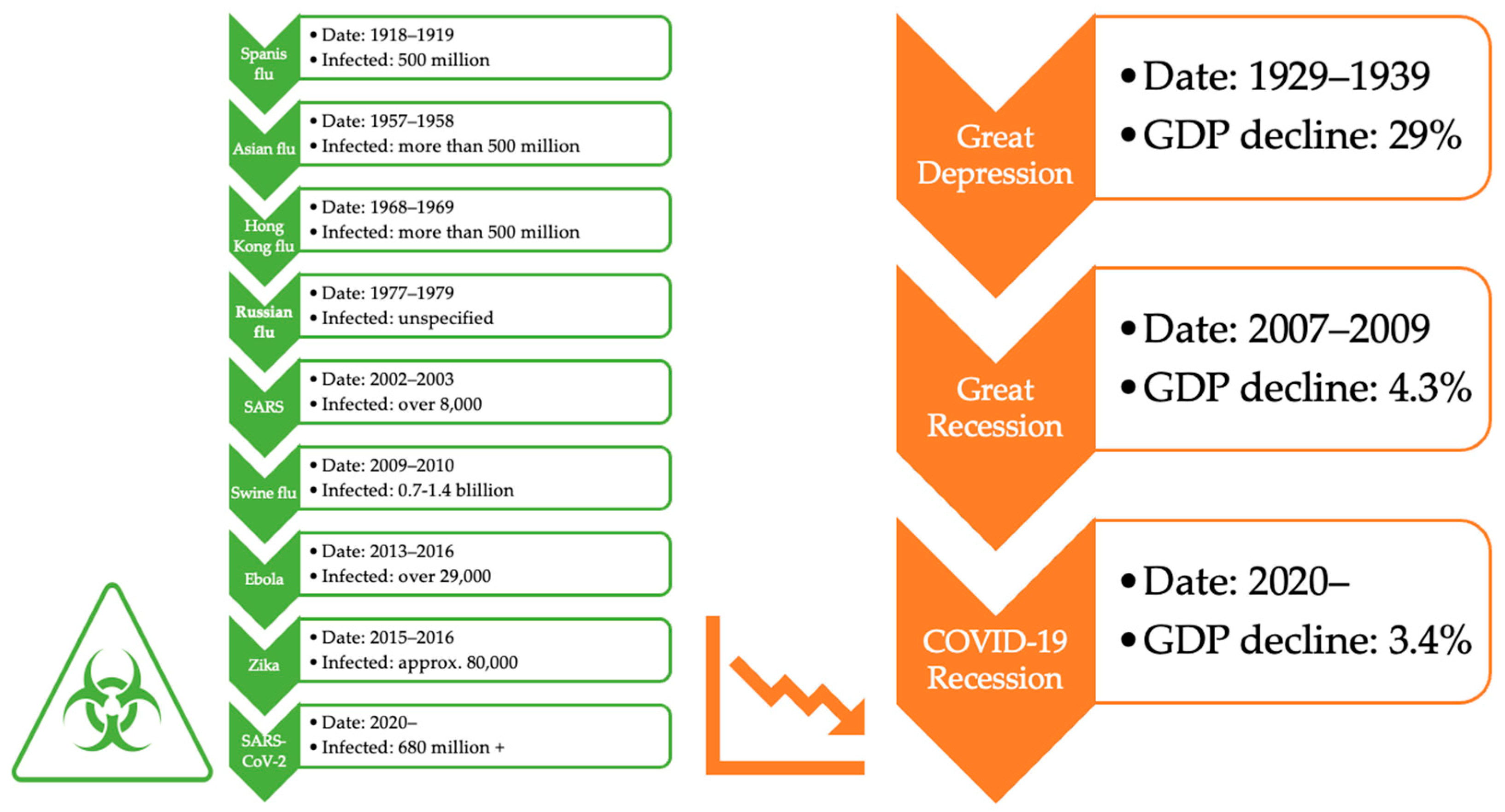

45] argue that for the first time in history, the extent of the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly affected both the global economy and financial markets. Finally, in the context under study, it should be noted that the world economy has faced several pandemic crises in the last century. Nevertheless, when considering the scale and consequences, it is clear that the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, commonly referred to as COVID-19, has had the most significant impact on the current economic situation. In contrast, neither the COVID-19 pandemic nor the previous pandemics can be directly attributed to the credit crunches we have examined in our research. These credit crises are, to some extent, a by-product of economic crises and their subsequent consequences. The following

Figure 1 visualizes the timelines of economic and pandemic crises as follows:

4. Conclusions

The global economy is a complex and fragile ecosystem with the global market at its core. Within this ecosystem, market participants move in a turbulent environment shaped by the interplay of internal and external forces. The COVID-19 pandemic has undoubtedly become a significant external dynamic that is having a major impact on the current global market. However, the diminishing impact of COVID-19 is not the only health crisis affecting the current market economy. In order to provide a comprehensive understanding of economic crises in the context of pandemics that have spanned the past century, this article places particular emphasis on the key role of financial markets, which serve as fundamental indicators of global economic turbulence. Our analytical approach relies largely on secondary sources within the academic literature, which are further strengthened by valuable insights contributed by experts in the field. The approach includes analytical and synthetic methods, which are complemented by decomposition and abstraction techniques. The core of our efforts lies in the synthesis and consolidation of a diverse body of knowledge that brings together multiple perspectives on this complex topic. Within this framework of contextual examination, it is clear that the COVID-19 pandemic does not exist in isolation. Rather, it forms part of a broader story of pandemics that have left an unforgettable mark on the world economy over the past century. However, the unprecedented scale of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has had a profound impact on the economy and financial markets, overshadowing the impact of all previous pandemics in modern history. This observation raises the intriguing idea that this pandemic-induced crisis is closely linked to the growing interdependence of the world economy. This raises an urgent question: will this interdependence continue to grow and foster even deeper global economic interconnectedness, or could future challenges force a rethinking of the interconnected global economic environment? In overcoming the challenges of pandemic crises and their implications for the global economy, further research and analysis is recommended to better understand the dynamics of interdependence, resilience and adaptability in the face of unforeseen external shocks. Such research can inform policy decisions and strategies to mitigate the impact of future crises on the global market.

The study highlights the lasting economic impact of pandemics and underscores the critical need for prudent planning in response to health crises. At the same time, it highlights the increasing interdependence of the world economy, which makes it more vulnerable to external shocks such as pandemics. As a result, robust strategies need to be put in place to mitigate this vulnerability. The research findings further suggest that global economies need to place a strong emphasis on resilience and adaptability in order to effectively face unforeseen challenges.

Combining this knowledge, the following definition can be formulated: market is a place where the forces of supply and demand meet. They are also a means of creating a complex network of economic interdependencies. At the global level, this discourse refers to the overarching realm of the world market, which is the fundamental framework on which the global economy is based. The global economy functions as a complex ecosystem. A pandemic economic crisis is a profound and widespread economic disruption caused by a global pandemic, characterized by unprecedented scale, economic and financial impact, and a critical need for research and policies to address the challenges and vulnerabilities of global interdependence.