1. Introduction

The territorial brand is a global development strategy. It has been utilized by over 50% of countries worldwide since the 1980s. Spain was the pioneer in creating its first brand. This process involves establishing an association between a territory and a brand. The brand serves as a distinctive sign and provides recognition. It also acts as a mediator for the social actors engaged in the production and development of the territory. This scientific essay discusses the state of the art of territorial brands. It is based on interdisciplinary theories of territorial and regional development. The goal is to analyze the contributions of territorial brands to policy, theory, and development analysis in multiple dimensions.

Creating brands for countries, regions, and cities is part of place branding, as proposed by Anholt [

1]. Place branding aims to establish a reputation for places in different spatial settings [

2,

3,

4,

5]. The concept revolves around unifying a core set of ideas that drive and differentiate these places [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Place branding is often associated with economic and tourism development and encompasses a complex process involving various strategies. According to Cleave et al. [

11], place branding has gained increasing importance in economic and regional development due to global competition for business investment. Territorial brand, an integral part of this process, serves as a strategy for legitimizing social actors’ discourses, as Almeida emphasized [

12]. This implies that the theme extends beyond exclusive associations with business investments, economic growth, and tourism development. Instead, it encompasses multiple dimensions of regional development.

Several authors have made significant contributions to place branding to emphasize the importance of place as a source of identity and competitiveness. Mihajlović [

13] explored the role of discourses in shaping regional identity and formulating regional development strategies. The study concluded that discourses play a crucial role in regional identity formation and provide valuable frameworks for regional policies. Oliveira [

14] emphasized the need to consider collaborative branding strategies to build regional advantage. These strategies aim to position regions, increase visibility, and incorporate discourses. An example of such an advantage is recognizing artisan products as a form of social capital in territorial and regional development [

15]. Bowen and Miller [

16] highlighted the economic impact of craft products, like beer, on local economies through the concept of “social terroir”. This concept fosters social and economic sustainability by connecting local social actors and utilizing marketing strategies to stimulate tourism. It also extends to terroir-based products, such as wines and sparkling wines, which receive brand through geographical indications.

Almeida and Cardoso [

17] introduced a novel classification for territorial brands, citing examples such as the Vale do Vinhedo in southern Brazil and the Champagne region in France. Both examples utilize territorial brands to promote various forms of development, including social, economic, regional, and sustainable development. Pinheiro et al. [

18] highlight that regions experience economic complexity and tend to diversify as they evolve. The authors note that the diversification process has positive aspects in terms of economic development. However, it can also have negative consequences, contributing to regional inequalities. Goodwin [

19] and Harrison [

20] emphasized delineating regions based on a hierarchical structure of ‘territorially rooted’ socio-spatial scales.

On the other hand, the relational view regards the region as open and discontinuous, shaped by a network of connections. The authors considered the need for interaction between these elements in different contexts and moments to ensure the overall coherence of social and capitalist formations. Therefore, with the growing demand for sustainability and the constant transformations in cities, regions, and countries worldwide, complex scenarios arise where the territorial brand becomes increasingly prevalent.

Notably, there is a significant need for more scientific research to understand the importance of territorial brands for regional development, especially considering the rapid transformations occurring in urban society [

12]. Previous research has outlined various perspectives on place branding [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25], but few have specifically focused on the link between the theme and regional development. The study primarily relied on Almeida’s [

12] research on territorial brands as a cultural product in regional development. It highlights the complex relationship between brands and territories, sometimes resulting in a marketing logic.

This study raises an important issue about using terminologies from other areas in specific contexts, which can lead to misunderstandings and misinterpretations of their meanings [

17]. It is important to note that terms such as “brand” and “logo” have distinct meanings in the specialized literature on branding and marketing [

26,

27]. Therefore, considering that creating a logo for a city or country will automatically result in a territorial brand is inadequate. In this case, the action would be merely an isolated advertising promotion initiative by governments aiming to boost the local or national economy for a short period. Moreover, differentiating the government brand, which can change every two or four years, from the territorial brand is essential. When examining the territorial brand as a cultural product, it becomes evident that multiple social actors play a crucial role, including the territory itself. This involvement encompasses various dynamics, territorialities, interests, strategic collaborations, conflicts, and partnerships, contributing significantly to regional development.

By creating a territorial brand, social actors form a vast network of internal and external relationships that influence the production of the territory. In this sense, Almeida [

12] addresses regional development through the territorial brand, highlighting that social actors create narratives that build and strengthen the identities of places, promoting different types of development, including regional development. The discussion also involves reflecting on the centrality and protagonism of cities [

28] that have a territorial brand, configuring themselves as strategically marked spaces.

How regional development theories are applied to the discussion of territorial brand is the central question of this study. The territory is a social and collective product “branded” like a commodity. However, this “branding” is more complex due to the complexity of the territory itself. When a brand is assigned to a territory, regardless of its geographical scale, this act influences the territorial and regional dynamics, requiring efforts for its operationalization. Thus, the territorial brand uses strategies that confer the status of the protagonist social actor to the territory, although this dynamic is not readily perceptible.

According to this argument, the territorial brand provides the territory the role of social actor and protagonist, suggesting that it is the territory itself, not the actors who occupy it, who seek to realize their interests in the produced space. This perspective leads the “branded” territory to become the voice of all social actors in the discourse when it only represents the interests of a specific group of social actors. Territorial brand is a stratagem social actors use to legitimize their interests in each territory. This stratagem can be subtle, efficient, and effective if used correctly.

This study aims to explore the conceptualization of the territorial brand from two approaches to regional development: cultural studies and urban studies. This theoretical debate seeks to understand why social actors create a brand for a particular space and the relationship that unites the brand and territory. Almeida [

12] argues that the creation and management of a brand expose the existence of a power structure to legitimize the interests of social actors through the discourse contained in the territorial brand. In this sense, the discussions proposed in this study seek to expose different perspectives on the territorial brand as a cultural product within the framework of regional development. Moreover, branding has a sociocultural approach that extends to territorial brands, making them dependent on a plurality of social actors [

29] and their narratives [

1,

2,

3,

30,

31,

32].

Understanding territorial brands implies understanding their capacity to influence the production of space and territorial dynamics. However, understanding these brands also demands understanding their territorialities. In this sense, Almeida [

12] says that for a territorial brand in the scope of regional development, there must be dual territorialities (that of the social actors and that of the brand), one territoriality being intrinsic to the other. The literature discusses that branding a territory can generate the construction of narratives that promote the place, stimulating different types of development, including regional development. Moreover, territorial brands are more than their logo, as they subjectively convey the ideologies and beliefs of social groups. The dynamics of these brands diffuse discourses that naturalize implicit interests of social actors, influencing the representations, identities, and power relations of and in the territory. The sociocultural approach to branding implies a plurality of social actors involved in creating and managing territorial brands, reflecting the narratives and ideologies of these groups [

1,

2,

29,

30,

31,

32]. The analysis of these aspects is fundamental to understanding the relationship between territorial brand and regional development.

The article contributes to the existing debates, placing place branding in the field of academic and scientific investigation of regional development through territorial brand. Thus, the area of place branding studies is expanded, encompassing an area of knowledge not usually associated with the theme. When one leaves the local scope and enters the regional, territories can only sometimes identify and value their internal potential. The discussion extends to how a territory is transformed into a territorial brand and becomes part of the management through place branding. By thinking and articulating branding as a development strategy (territorial and regional), the territory’s identity and dynamics become stronger, stimulating a sense of regional unity. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the role of place branding, but in addition to places, regions also need to be prepared to adopt a brand that represents them. Otherwise, there will be isolated marketing or advertising actions applied in each geographical space.

Thus, place branding plays a vital role in a region’s development if the internal character of the region is maintained. In turn, regional development promotes the local, allowing regions to be considered a set of territorial brands articulated by an endorsing brand, that of the region. This research paper provides an expanded understanding of place branding, further exploring its role in regional development through the territorial brand. The facets identified in this research can provide practical and valuable constructs for place branding practices. Therefore, they can become the basis of a proper place branding framework with a more generic application in terms of regional development.

1.1. Methodology

The methodology relies on bibliographical research encompassing discussions on the theories of regional development (such as cultural, urban, and regional studies) and place branding. Consequently, this study does not employ case study details, focusing on the theories that shape the concept of “territorial brand in regional development”.

Bibliographical research is an appropriate methodology for investigating the theme proposed in this study. This methodology provides an overview and a deeper understanding of the topic. Thus, the methodology adopted in this research consisted of a review and critical analysis of the main theories about regional development (cultural, urban, and regional studies) and place branding in the scientific literature. As a result of these sources’ analyses, knowledge will advance regarding the theme of a territorial brand in the context of regional development.

1.1.1. Method

The inductive content analysis allowed the identification and interpretation of the information collected (even if scarce) from the available literature on the concepts of regional and territorial brand development and the relationships between them [

33,

34]. Almeida’s [

12] study was the only one that addressed this issue, providing the basis for this study. Thus, two broad concepts guided the theoretical discussion to achieve the study’s objective, arriving at the interdisciplinary discussion of a territorial brand in the scope of regional development.

In addition, three questions originating from the objective supported the study:

- (1)

What are the theoretical discussions on territory that serve as a stage for the territorial brand?

- (2)

What territorialities are involved in the territorial brand?

- (3)

What theoretical discussions have recently been involved in the territorial brand?

Finally, the paper answers the central question of how the territorial brand discusses regional development theories. Thus, the objective is met, through theoretical arguments, allowing the exploration and conceptual discussion of the territorial brand from primarily three theories of regional development: cultural, urban, and regional studies. Cultural studies are an interdisciplinary field of research that explores how meanings are produced, created, and disseminated in society [

35,

36]. Urban studies are based on the study of city development, considering everything related to life in the city and to the individuals who inhabit it, except the rural [

37,

38]. Regional studies investigate regional logic to act and modify the territory concretely and abstractly, according to what target interests someone or a social group. It appropriates space as a form of regional planning through representation [

39,

40].

In addition, the paper adopts the theoretical essay format, which, according to Jones [

41] and Jaakkola [

41], makes it possible to explore findings and deepen interpretations on a topic. Supported by illustrative cases arranged in the discussions in

Section 4, the study exposes the theories that support the relationships between territorial brand and regional development. The existing literature on place branding needs to address regional development, and this study is an opportunity to introduce new theories to the observed gap.

1.1.2. Data Collection

The data collection originated from articles published in the Scopus platform that presented, even minimally, relationships with the theories investigated in the study. Thus, from the keywords “territorial brand” AND “regional development”, three results emerged [

8,

17,

42]. Furthermore, through the snowball technique [

43], the Scopus articles led to other articles used in the research. Acting in this way was necessary because, except for Almeida [

12], no publications referred directly to the relationships between territorial brand and regional development, and its use in this study was appropriate.

The study was conducted based on two keywords related to a previous study [

12]. To be selected in this research, the articles published needed to have a relationship between the two topics. If a study focused only on economic development, it was discarded because it focused on regional development. The title and abstract of the manuscript were considered in the initial phase to establish this relationship. In the second phase, the selected articles were read in their entirety. Only three studies were considered among the Scopus publications because they presented a clear connection between the keywords.

The snowball technique was used to broaden the scope of the publications. Thus, the references used by the authors of the selected studies led to other articles and so on if there was a connection with the keywords mentioned. This approach resulted in 13 studies included in

Table 1, showing the contributions and limitations of each one.

In addition,

Table 1 presents the correlations between place branding and regional development. This strategy was adopted because territorial brand is present in both theories but in different ways.

1.1.3. Data Analysis

The research employed an inductive content analysis to interpret the data collected from recent publications by comparing them with illustrative cases.

1.1.4. Rigorous Study Selection, Data Analysis, and Interpretation of Results

The rigorous selection of the studies included in this study was ensured through clear and objective criteria. The keywords “territorial brand” and “regional development” were used to identify relevant studies on the Scopus platform. From the results obtained, we applied selection criteria that considered the direct relationship between the topics and the approach to the concepts investigated. The small number of selected articles does not invalidate the study, but makes it clear that the theme has not been explored in depth in the specialized literature. This fact is already a result of the research.

After the studies were selected, an appropriate analysis of the collected data was performed. The articles were read in their entirety to obtain a comprehensive understanding of their contributions and limitations. Special attention was given to how the studies addressed the relationship between territorial brand and regional development.

The interpretation of the results was based on the theories discussed in the literature review and the information collected in the selected studies. Inductive content analysis was applied to identify patterns, trends, and insights relevant to the study’s theme. Interpretations were based on the data collected and supported by relevant theoretical references.

Thus, a rigorous selection of studies, an adequate analysis of the data collected, and a reasoned interpretation of the results were key aspects considered in this study to ensure the quality and reliability of the conclusions reached.

1.1.5. Organization of the Study

Three parts organized the study. The first part introduces the theme of the territorial brand. The second part discusses the concepts of territory, territorialities, and territorial brands, crossing urban and cultural studies. Finally, final considerations appear.

3. Territorial Brand in Regional Development—Theory

When regional development is addressed, discussions of place branding are minimal or absent. However, the regional development concept is typical, depending on the philosophical current addressed. For Vazquez-Barquero [

62], Sotarauta [

63], and Cappellin [

64], for example, regional development is about transforming its endogenous potential into active resources toward a specific problem. However, territorial brand only sometimes comes from this context and is managed in ways other than through place branding. The territory suffers internal and external influences, including to be, in what Anholt [

2] called, a global map of places. The use and articulation of territorial brand as a regional development strategy will also depend on the interests of social actors in the use and appropriation of a collectively produced space. Notably, the “regional” scope is formed from local environments, such as cities.

Jokela [

41] highlights two debates about branding cities. One debate highlights a differentiation strategy of entrepreneurial cities engaged in interspatial competition. The proposed discussion intersects with the studies of Harvey [

65], who offers critical insights into the utilization of corporate strategies in urban management. For example, Portugal’s capital, Lisbon, adopted in 2017 a new territorial brand, generating the reputation of an entrepreneurial city [

66]. This reputation derives from a private power event associated with startups. Thus, the Lisbon brand seeks to “transform” the city into a great business incubator. Jokela [

41] mentions another case of urban entrepreneurship, the brand of the city of Helsinki. Helsinki’s strategy is to transform the city into an entrepreneurial and facilitative platform linked to entrepreneurship extended to society. Brown et al. [

67] use another terminology, called entrepreneurial ecosystems (EEs), associating it with regional clusters. The author’s terminology is also addressed to cities and regions that call themselves entrepreneurial, criticizing the simplistic appeal of EEs due to places not being like people. In this sense, Almeida [

12] also mentions that brands and territories are not people to be protagonists of something in the discussion about territorial brands. However, personifying an object or something that is not human is a strategy used by marketing to connect “things” to people and institutions. This means that approaching territorial brand also refers to the strategies of a reputation of places through power relations, personifying the territory as a protagonist social actor.

Moreover, it is a territorial marketing strategy aimed at local development. Ashworth and Voogd [

68] proposed steps to build a territorial brand involving research, competition analysis, the definition of a positioning strategy, implementation, and monitoring. Therefore, both Lisbon and Helsinki, illustrative cases of this study, use this strategy to generate development, especially economic development. It is necessary to clarify that economic development is a part of regional development, but it is not only economic issues that qualitatively build a region. This perspective is the most significant confusion that the regional development concept carries, leading to different perspectives on territory and region.

Kurikka et al. [

69], in turn, contemporaneously remodels Harvey’s [

65] concept when referring to “Regional opportunity Spaces”. The new perspective sustained by the authors addresses how social actors seek and construct opportunities in regions, linking opportunity spaces to the social filters that shape people’s perceptions. Although presented as a new perspective, the terminology of Kurikka et al. [

69] is like that of Harvey [

65], Jokela [

41], and Brown et al. [

67], in that the directive of entrepreneurship is the provision of opportunities. One of these “entrepreneurial” “opportunities” refers to the creation of territorial brand for cities, regions, and countries to meet the demand of globalization and to be present in what Anholt [

2] called a “global map of places”.

The second debate presented by Jokela [

41], also discussed by Lucarelli [

70], considers place branding as an urban policy and a form of planning. As a form of planning, Almeida and Rezende [

66] exposed territorial brand as an urban instrument that contributes to urban planning. However, the presence of the territorial brand, in the case of Brazil, for example, could be more extensive in urban planning and regional tourism plans. Authors such as Eshuis and Edwards [

71] pointed out that place branding has influenced ideas about communities and districts, especially in urban regeneration programs. From this perspective, branding is a new governance strategy for citizen perceptions of public management. Eshuis and Edwards [

71], both from the field of public administration, pointed out that this is one of the roles of place branding. Anholt [

1] points out that place branding generates a reputation for the city, while, for Almeida [

12], government brand differs from place branding and territorial brand. Here is an example of confusion in other fields’ branding terminology.

The confusion begins in choosing two strands, whether branding and marketing are synonymous. This essay starts from the perspective that the terms are not the same, although they come from close origins. Branding is the strategic management of brands [

71] and may extend to government brands from a neoliberal governance perspective. However, despite being a micro aspect of brand, place branding does not address corporate or public brands (government brands) but the brands of territories at different scales (countries, regions, cities, and streets). A government can create a brand for the city (top-down format), as in most of the specialized literature on the subject and in empirical cases, or a city can create its brand in the bottom-up format, regardless of the government (e.g., Helsinki, Lisbon, Dals Långed). The culture, as a power structure [

72], plays a central role in territorial branding, because it is where its basic material is found.

The symbolic dimension builds the territorial brand and is mediated by the brand’s and social actors’ territoriality, leading to what Almeida [

12] called “double territoriality”. As a cultural artifact, the territorial brand is within cultural studies highlighting the influence, not dependence, on political–economic relations. From this view, culture becomes a product that extends beyond its economic nature. From this transformation, cultural studies emerge as communicative processes in apprehending culture and how society is organized. Thus, communication is a means of spreading culture and its forms of production, building sense and meaning for its processes.

The relationship between culture and communication is, therefore, characterized by dependence. In this context, the territorial brand becomes an integral part of regional development. Its cultural and communicative nature plays a crucial role in transmitting values, reputations, discourses, territorialities, and power relations. For Almeida [

12], the territorial brand seen from the viewpoint of regional development encompasses four axes: brand, territory, strategic articulations, and dual territorialities. The territory is remolded by the power relations that are established and by those that are in dispute with the hegemonic power. The legitimacy of the discourses of social actors finds a strategic and articulated ally in the territorial brand. Culture and communication are inseparable, and the media mediate a symbolic and ideological power in constant conflict and consensus [

73,

74].

The territorial brands use the media to achieve their purpose, spreading an intentional discourse of social actors. Discourses are (de)legitimized, and identities are (re)created or (re)invented in the establishment of territorialities and ideologies contained in the territorial brand. From cultural studies [

73,

75], the territorial brand produces meanings in which a social structure of power exists. The concept’s interdisciplinary nature stems from continuous transformation, interrogating everyday practices and their relationships, revealing hierarchies and power ties [

73]. Similar to how the author of a work (the artist) also expresses the point of view of his group or social class in his works, providing them with a social stamp, the territorial brand, when created, reveals, through culture, the discourses and ideologies contained in the territory it represents. With this understanding, Almeida and Cardoso [

17] developed a novel typology of territorial brands, exposing the ideologies and discourses of social actors in territorial and regional representation.

Table 1 presents the theories’ main contributions and limitations on place branding and regional development related to territorial brands.

Table 1.

Theories and correlations between place branding and regional development.

Table 1.

Theories and correlations between place branding and regional development.

| Authors | Theories | Correlations between the Theories |

|---|

| Contributions | Limitations | Place Branding | Regional Development |

|---|

| [68] | They created steps to build a territorial brand, focused on entrepreneurship. | Entrepreneurship synonymous with economic capital. | The steps involve: research, competitor analysis, definition of a positioning strategy, implementation, and monitoring. | Place branding theory linked more to economic development. |

| [62] | Endogenous capital as a territorial asset. | Disregards the power of economic capital in the development of a region. | Strengthening the image and reputation of the site. | Importance of endogenous capital for the region and its development. |

| [64] |

| [63] |

| [65] | Entrepreneurial cities engaged in an interspace competition. | Positioning entrepreneurship tied only to economic capital. | Place branding as tool for territorial competitiveness. | Seen as a differentiation strategy for entrepreneurial cities engaged in interspace competition. |

| [41] |

| [2] | Creating the image and reputation of places through place branding. | It only considers the local scale. | Places managed as if they were brands. | Endogenous regional development, until 2018, did not include the discussion of place branding. |

| [71] | Applying branding in urban regeneration areas. | Link to economic development only. | Role of branding as a governance strategy in managing citizen perceptions of public management. | Relationship in the political role of regional development. |

| [70] | Association of place branding as public policy. | It only considers the local scale. |

| [12] | Creation of the concept of “Territorial brand in regional development” realized from the theories of endogenous regional development on multiple socio-spatial scales. | Separation of the concept of brand and branding, delimiting the scope of the concept. | It inserts the power relations in the construction, maintenance, and dispute of brands linked to territories and regions. | Territory is remolded by the power relations that are established and by those that are in dispute with hegemonic power. |

| [67] | Entrepreneurial ecosystems (EEs), associated with regional clusters. | Criticism of the simplistic appeal of EEs due to places not being people. | Place branding is used to identify ideas about communities and districts, especially in urban regeneration programs. | Regional clusters can be associated with regional development through economic gain for the regions. |

| [69] | Creation of the concept of “Regional Opportunity Spaces”. | Focus especially on economic capital as the transforming element of the region, without considering other elements vital to regional development. | Local reputation associated with opportunities arising from entrepreneurship. | It concerns how social actors seek and construct opportunities in regions, linking spaces of opportunity to the social filters that shape people’s perceptions. |

| [17] | Creation of the “TRBrand” classification model. | The typologies considered are only those that come from the theories of regional development and place branding. | Creates a typology of territorial brand associated also with place branding and regional development. | New typology of territorial brands linked to regional development. |

The theories discussed in this study present a theoretical–interdisciplinary basis in which place branding and regional development meet in different contexts through the territorial brand. Regional development was distant from place branding until Almeida [

12] correlated the territorial brand as a product of regional development, extending beyond economic development. The study sought to bring these concepts closer together (

Table 1), resulting in a complex discussion for territories and regions “marked” by territorial brands and management by the process of place branding. This perspective shows that the relationship between brand, territory, and region is complex and is only sometimes observed in these areas, approaching a new interdisciplinary theory.

Thus, this research employs Almeida’s concept as its foundation, as it encompasses a broader scope than previous concepts that solely address economic and touristic development.

“The concept of the territorial brand because of the cultural approach of Regional Development refers to the creation of symbolic value, the articulation of the actors as to the plurality of identities present in a territory, the way they use this brand and make it a significant asset for the territory and, consequently, for the region. In addition, the construction of narratives about the territory and the strategies used to construct a brand that articulates a set of actors are incorporated into the concept. The territorial brand is, therefore, a multifaceted concept that can be understood as an intentionally organized movement between elements, discursive and visual, articulated by social actors of a given territory that draw on culture and territorial identity to create a specific brand for that space, distinguishing it from others” [

12] (p. 247).

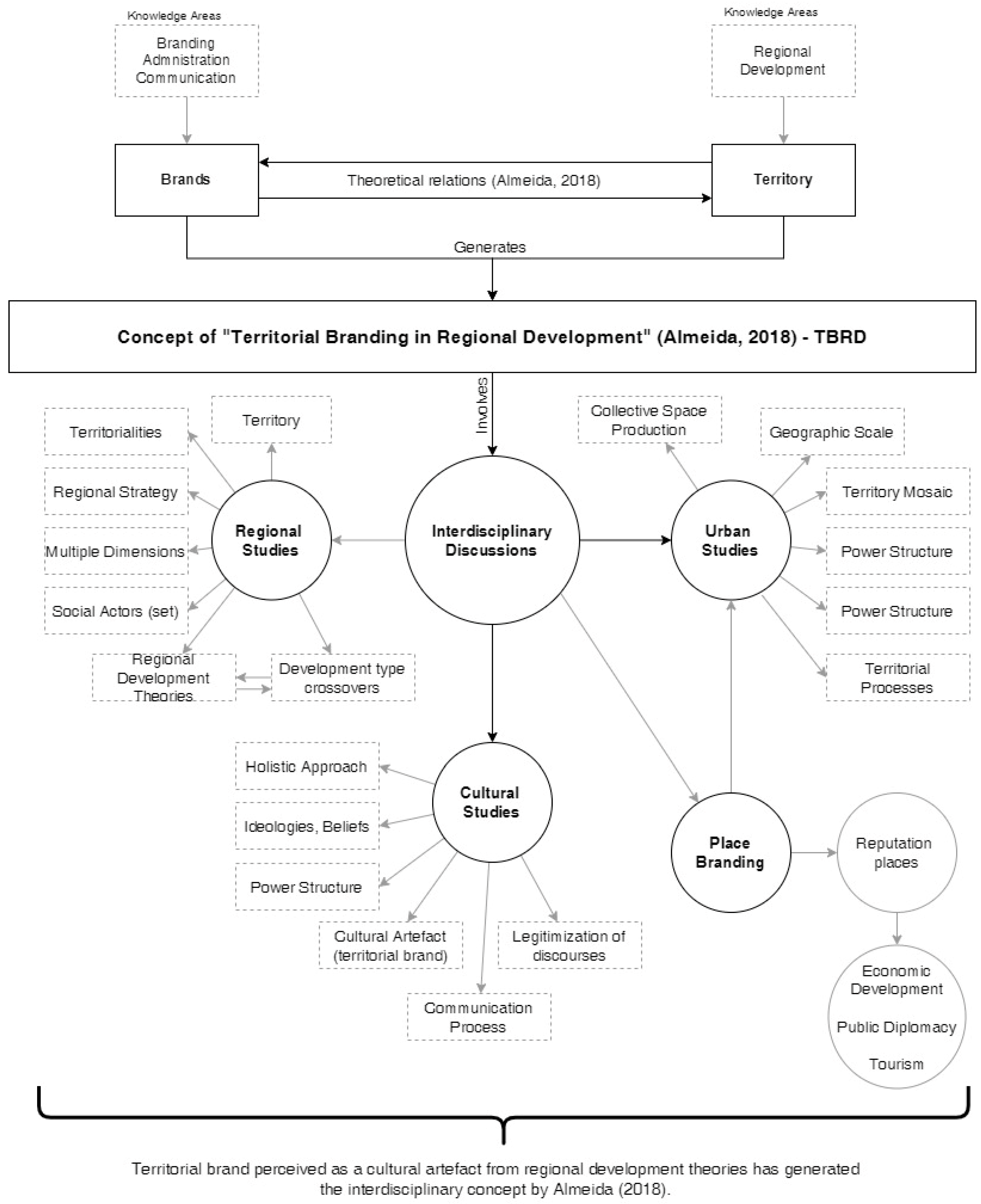

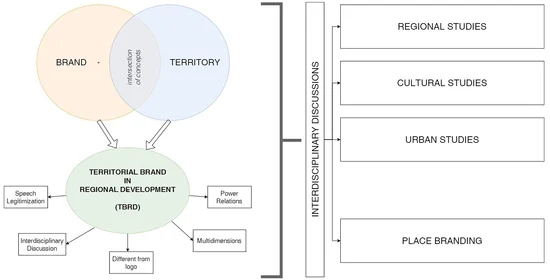

The discussions proposed in this study generated the conceptual model of the territorial brand investigated from the theories of endogenous regional development (

Figure 1) and the concept of “territorial brand in regional development”. It is important to note that the “Theoretical Integration of Regional Development in Territorial Brand- Model” starts from a model originally proposed in 2018. Furthermore, the model (

Figure 1) emphasizes the importance of an integrated approach, combining theories of regional development and territorial brand.

The model presented exposes the interdisciplinary discussions that involve territorial brands in the context of regional development. It is perceived that the involvement of place branding as a territorial management process is mainly focused on economic development.

Large areas of knowledge cover the initial concepts of brand and territory, located at the central top of the model. From the analysis of the theoretical relationships between these themes, the concept of the “territorial brand in regional development”, proposed by Almeida [

12] emerged. Thus, the 2023 conceptual diagram represents an expansion of the original research conducted in 2018.

Drawing on regional development theories and interdisciplinary discussions, the territorial brand emerges. It is an approach that examines the territorial brand from multiple theoretical perspectives, considering mainly three significant areas of study: regional, cultural, and urban. These studies are intertwined with the theories of place branding, resulting in a hybrid theory encompassing the territorial brand. A territorial brand should be considered a cultural artifact in endogenous regional development. This artifact incorporates a power structure capable of legitimizing the discourses of social actors about and within the territory. These discourses also extend to the regions in their multiple scales. Therefore, this is a complex discussion that culminates in the formation of a new theory for regional development.

At the same time, the model generated also presents a set of research proposals for future studies.

4. Conclusions and Prospects

The proposed discussion met the study’s objective by reflecting on the territorial brand from the theories of regional development, particularly cultural and urban studies, with the specific objective of identifying the reasons social actors create a territorial brand. The arguments developed in the reflection of this essay were based on interdisciplinary studies already carried out, such as those of Hall [

73], Hoggart [

74], Williams [

72], Thompson [

75], and Almeida and Cardoso [

17]. From this debate, some motives that lead social actors to create a territorial brand emerged, such as the need for differentiation, the construction of identities, and the legitimation of discourses. The “brand” of a territory (city, region, country, street, square) crosses territory, territorialities, and place branding, becoming a complex discussion affecting urban, regional, global, and contemporary societies differently.

The debate about the territorial brand from the theories of regional development was only possible after realizing that the concept of territory is in its essence. When there is no such perception, there is only a logo applied commercially to the territory, but there is no brand that spreads beliefs and ideologies. The “brand” of a territory takes place because it is a social and collective product, albeit a complex one. The study indicates that the territorial brand in the scope of regional development results from processes of (dis)order and (re)ordering in producing a space collectively delimited by power relations. Thus, the territorial brand of a city does not refer to all the spaces of a city, but only to some spaces (or fragments of territory) intentionally chosen by social actors. This situation is discussed by Coy [

58], who sees the city as a mosaic of territories.

4.1. Contributions

Territorial brand follows the theories of regional development, especially endogenous development. Significant logical contributions to the academic and scientific field explore the relationship between territorial brand and regional development. These contributions span a period dating back to the 1980s and have relevance in multiple skiffs.

The contributions extend to broadening the field of studies on place branding. By introducing the concept of territorial brand as a cultural product in the context of regional development, the essay extends beyond traditional approaches that focus only on the economic and tourism investments of places. The research recognizes the territorial brand as a strategy that legitimizes the discourses of social actors and encompasses various dimensions of regional development. Moreover, the study adopts an interdisciplinary approach, incorporating territorial and regional development theories and cultural and urban studies. This perspective allows for the analysis of the narratives and ideologies of the different social groups involved in creating and managing territorial brands.

Additionally, the essay discusses territorial dynamics and the dynamics of identity. By investigating how territorial brands influence the production of space and territorial dynamics, the study covers the debate of territorialities (social actors and brands). Finally, practical contributions identify important facets, providing elements for constructing the “Theoretical Integration of Regional Development in Territorial Brand-Model”. These are the logical and global contributions of the manuscript, highlighting its relevance in expanding the knowledge about a territorial brand and its relations with regional development.

4.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

Providing a reflection on the importance of the debate on territorial brand in the development of regional economies is the purpose of the study. Through an interdisciplinary approach, the discussions presented in this research highlight some issues surrounding territorial brands. The topic is relevant from theoretical and empirical perspectives and contributes to opening broader dialogues in regional and global perspectives. Thus, a multidisciplinary dialogue can highlight what is at stake in debates about cities, regions, and countries in the context of regional development. Thus, this study can be helpful for researchers, students, place branding, and local government managers in applying multiple concepts to aid local and regional planning.

The results indicate that regardless of the top-down or bottom-up process, the territorial brand can negatively or positively impact cities, countries, and regions, depending on the interests of the social actors who produce that space, differentiating territories among themselves. Another direction points to the presence of the debate on the territorial brand in the scope of regional development, but still in a timid way.

Thus, the interdisciplinary approach highlights regional discussions involving the territorial brand. The research is relevant from theoretical and empirical perspectives and seeks to open up broader dialogues from regional and global perspectives. A multidisciplinary dialogue can elucidate the issues at stake in debates about cities, regions, and countries in the context of regional development. The results indicate that regardless of the top-down or bottom-up processes, the territorial brand can positively or negatively impact cities, countries, and regions, depending on the interests of the social actors that produce this space, differentiating territories from one another.

The research also has value in filling this gap and providing important insights for researchers, students, place-branding professionals, and local managers.

4.3. Limitations of the Research and Future Suggestions

Despite the study’s limitations, it is acknowledged that it analyzes the territorial brand in isolation related to regional development without exploring the various types of development and their relationships. The intersection of the various types of development in the territorial brand is presented as a future research suggestion, building a research agenda on the topic. Moreover, the format of a scientific essay is short, requiring clipping into the broad discussion of which the territorial brand is a part. The topic is broad but no less critical for regional development. It is also suggested that studies be carried out with details of cities, states, and countries compared among themselves. The construct of economic clusters needs further discussion within the paper.

4.4. Proposals for Future Research

Based on the findings and discussions presented in this study, several propositions for future research can be put forward. Firstly, further investigation is needed to examine the long-term effects of territorial brands on regional development. This could involve longitudinal studies that track the evolution of territorial brands and their impact on economic, social, and environmental aspects of the regions over time.

Secondly, an in-depth analysis of the role of stakeholders in the creation and management of territorial brands would provide valuable insights. Understanding the perspectives and motivations of various actors, such as local governments, businesses, community organizations, and residents, can shed light on the dynamics and effectiveness of territorial branding initiatives. Additionally, exploring the cultural dimensions of territorial brands and their influence on regional identity and community cohesion would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of this phenomenon. This could involve qualitative studies that delve into the narratives, symbols, and rituals associated with territorial brands, and how they shape the sense of belonging and attachment among residents.

Furthermore, comparative studies across different regions and countries can provide insights into the contextual factors that influence the success or failure of territorial branding strategies. By examining cases with varying levels of economic development, cultural diversity, and governance structures, researchers can identify best practices and lessons learned that can inform future territorial branding efforts.

Lastly, the exploration of innovative approaches and technologies in territorial branding is an area ripe for further investigation. The emergence of digital platforms, social media, and data analytics presents new opportunities and challenges for the creation and management of territorial brands. Future research could explore the potential of these tools in reaching target audiences, measuring the effectiveness of branding campaigns, and fostering engagement and participation among stakeholders. By addressing these proposed research areas, scholars and practitioners can deepen their understanding of territorial brands and their implications for regional development. These studies can provide valuable insights and guidance for policymakers, local communities, and organizations involved in territorial branding initiatives.

4.5. Concluding Remarks

A plurality of dimensions is present in the relationship between brands and territories, connecting multi- and interdisciplinary insights systematically and grounded to understand how and why regions, countries, and cities create and use territorial brands. These findings are relevant to academics, researchers, policymakers, and brand strategists.

Several significant conceptual advances and constantly growing empirical insights from specific cases have contributed to refining the understanding of regional development. As a result, the territorial brand presents itself as a contemporary topic of regional development. Nevertheless, more is needed to know about the multidimensional effects of territorial brands for regions in the short and long term. Moreover, existing studies tend to not establish connections between brands, territories, regions, and development. Nevertheless, recent research indicates, albeit timidly, such approximations, highlighting the topic’s relevance for regional development.