Definition

Mozambique is a Southern African tropical country; it forms a 4330 km coastline on the Indian Ocean side. It is one of the continent’s five former Portuguese colonies, with the economy relying mainly on agriculture and mining.

1. Land and Society

1.1. Geography

The Republic of Mozambique (Figure 1) is a developing country located on the southeastern coast of Southern Africa [1,2,3], occupying 801,590 km2 [4,5] (13,000 km2 comprising inner water such as rivers and lakes [6]).

Figure 1.

Map of Mozambique.

The Indian Ocean forms its eastern coastline (4330 km) [6] and shares its southwestern border with South Africa and Eswatini (former Swaziland), western with Zimbabwe and Zambia, northwestern with Malawi, and northern with Tanzania [4,7,8]. Its temperatures are higher nearby the coast (25–27 °C during summer and 20–23 °C during winter) and reduce as one enters the continent [6].

Mozambique has eleven provinces, including the capital Maputo City [8,9]. The country’s southern region comprises Maputo City, Maputo province, Gaza, and Inhambane [10]. Maputo City, with 1,122,607 inhabitants [9], is the country’s busiest and most developed area and is relatively multicultural due to the increasing number of people from other provinces who study or find work opportunities [11]. The central region comprises Manica, Sofala, Tete, and Zambézia provinces, and the northern region encompasses Nampula, Cabo Delgado, and Niassa provinces [8].

The climate is tropical and humid [4]. Mozambique has a dry and rainy season [12]. The locals frequently describe the dry season as winter because the temperature decreases steadily from mid-April to mid-July and rises until mid-September [5,13]. The rainy season has a peak temperature between December and January [13] and floods might occur in some areas (e.g., Chokwe district) [14].

The rural areas frequently lack pipe water, electricity, and access roads [15]. According to Census 2017, 35% of Mozambican households have at least one radio and 21.8% have a TV, which is the primary media to disseminate information and spread awareness throughout the population [3,16]. The statistics presented show disturbing disparity, not only regarding access to media but also regarding real estate ownership.

Only 26.4% of the population has cell phones, 4.4–5.3% have personal computers, and 5.8–7% have access to the internet [3,9]. Most people with cell phones can hardly afford the prices from the providers [9]. Internet and information technologies are scarce and irregularly distributed in terms of availability and quality [9,17]. However, recent statistics show that internet users are increasing, especially in the Maputo province [9].

1.2. History

Mozambique has a distinctive cultural identity [18], with a unique and rich culture [1] inherited from early Bantu settlers with Arab merchants, Portuguese colonizers, and Indian immigrants, among others. Although secondary orality (written or graphic records) is the main form of the perpetuation of the population’s collective memory, a significant part of the cultural identity passes across generations through primary orality (spoken information), using, for instance, proverbs, poems, nursery rhymes, folk tales, and songs [2]. The scarcity of written records before Portuguese colonialism causes it to be difficult for scientists to fully grasp the extent of the population’s historical and cultural heritage [2,19].

The oldest written records about Mozambique belong to al-Masud, who described the markets of Sofala as a source of gold [20]. The country’s name came from Mussa ibn Biki, a wealthy merchant and sheik on Mozambique Island [21]. The first contact between the local population and Portuguese colonizers occurred at the end of the 15th century when Vasco da Gama stopped in Inhambane while going to India [22]. Then, the visits became more frequent until the Portuguese finally settled to strengthen the commercial relationship with the locals. Notable explorers include Lourenço Marques and António Caldeira [23].

Before Mozambique’s unification, there were empires such as Mutapa [24] and Gaza [25], with many accounts of prosperity, treason, and war. Portugal occupied Mozambique effectively after the Berlin Conference (1884–1885), when European countries claimed ownership of the African territory [26,27] and when Mouzinho de Albuquerque captured Gaza’s emperor Ngungunhane, the last before Mozambique became a Portuguese Province [27,28].

According to Magalhães [29], when Portugal occupied Mozambique, António Enes ordered Portuguese officers to replace the traditional leaders and the colony adopted, in 1907, the Minute of the Administrative Reform of Mozambique, which was initially adopted in the South and later colony-wide. Mozambique had a Governor-General and District Governors with authority over Administrators. The lowest administrative position was the regulo (small king), a native who dealt directly with the population. Portugal colonized Mozambique and other territories for longer than other European countries partly because it assumed the position of the metropolis of a multicontinental country rather than the image of a colonizer.

The war for independence between the Front for Liberation of Mozambique (FRELIMO) and the Portuguese lasted from 1964 to 1974 [30]. After the proclamation of independence on 25 June 1975 [8,10], few Portuguese stayed and changed their nationality to Mozambican. However, most engineers, scientists, and highly skilled people returned to Portugal or migrated to areas such as Rhodesia (now Zambia and Zimbabwe) or South Africa [31,32]. The economy struggled because there was very little qualified labor [33].

For the following post-independence years (1975–1989), the new government adopted a Marxist–Leninist orientation, with a single party and centralized rule [27]. However, a 16-year civil war (1976–1992), mostly in rural areas, created a political–economic destabilization [10,34] and production crises until the peace treaty in 1992, when Mozambique transitioned from state socialism to an increasingly neoliberalist regime [33]. The then rebels, known as the Mozambican National Resistance (RENAMO), had support from Ian Smith’s Southern Rhodesian and the South African apartheid regime. RENAMO was primarily dissatisfied with the communist government, in which no citizen could have private property. From their perspective, it was unfair to live in such conditions after the struggle for independence.

Despite the problematic post-independence situation, the population was highly motivated to help consolidate the nation’s pride and sovereignty, primarily due to the charismatic leadership of President Samora Machel [35,36]. For instance, the country adhered to the Green Revolution’s agricultural movement, intensifying production, adopting modern machinery, and using chemical pesticides and fertilizers [37,38].

Mozambique’s economy changed from communist to market-oriented, introducing the so-called Economic and Social Rehabilitation Program (PRES) in 1987 [27,39]. Sponsored by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), this program included the regime change to democratic multiparty, modernization of the economy and the mode of production, mass privatization of the government’s assets, voluminous foreign investment, urban expansion, and improvements in the healthcare system [33,39]. According to Langa [40], other political transitions were post-conflict, after the Peace Treaty in 1992, the multiparty elections in 1994, and the following political decentralization.

The regime change affects social relations, shifting from a closed to an open society [18]. However, Sambo and Guambe [41] criticized that despite several Constitution amendments, they aimed to consolidate the new State’s sovereignty, not necessarily the will of the different social classes. For instance, tribalism and social inequality are still frequent [42,43], and civic space, inclusiveness, and freedom of speech are deteriorating [44]. Aliança Moçambicana da Sociedade Civil C-19 [45] stated that economic disparity is increasing in Mozambique and worldwide, resulting from an economic system based on the development and accumulation of capital reliant on the exploration of workers and nature.

Since the millennium started, Mozambique became increasingly aligned with international policies, pursuing the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), followed by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), reflected in the country’s policies, such as the Plan of Activities to Reduce Poverty [27]. Mozambique thrives after a long history of severe disease outbreaks, geopolitical tension, economic crises, and natural disasters [14]. The Mozambican Constitution has a specific protocol for an Emergency State [46], but nobody expected to use it due to a worldwide pandemic.

1.3. Population

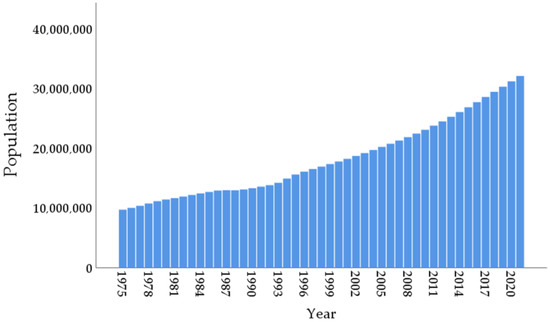

Figure 2 shows the population of Mozambique from 1990 to 2020. The period presented a constant arithmetic growth from approximately 12.5 million to almost 30 million citizens [47].

Figure 2.

Mozambican population and population growth from 1975 to 2021. Made by the author based on the data from The World Bank Group [48] and World Population Prospects [49].

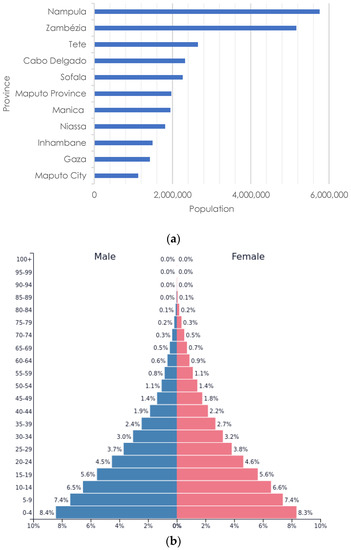

The General Population and Housing Census of 2017 [50] indicated 27,909,798 inhabitants (density: 39 inhabitants/km2 [34]), but projections from the National Institute of Statistics [51] estimated 30,832,244 inhabitants by 2021, 65% living in rural areas (67.2% of the private households), almost equally divided between men (14,885,787) and women (15,946,457). The northern and central areas are the most populated (Figure 3). The country’s southern area (Maputo City, Maputo, Gaza, and Inhambane provinces) has approximately 4 million people [10]. There are 6.3 million households [17]. The steady increase in the population is a significant reason why family planning is essential in Mozambique [52].

The population pyramid is typical of a developing country, considerably narrowing as one moves bottom–up. The population is predominantly young [10,53], with 16.6–17.6 years as the average age [10,53,54,55], 53% under 17, and a life expectancy of 60 years (in 2018) [56]. As for the main age groups: children and adolescents below 15 years old comprise 46.7% of the population, the group 16–45 years old is 38.5%, followed by 10.2% comprising the 45–59-year old, the cluster above 60 years old is 4.6% [55], and above 64 years comprise 3% [34]. The population is growing partly because of low adherence to family planning [57]. Countrywide, the use of contraceptives decreased from 17% in 2003 to 11.5% in 2011 and increased to 35% in 2019 [57,58]. If the trend remains, population growth will stabilize.

1.4. Culture and Religion

Besides being multicultural, Mozambique is multilingual [2,59]. It is among the five African countries with Portuguese as its official language [3], spoken by 37.7% of the population [2,8], used in the anthem, all official documents and communications, and the National Educational System (SNE) [8], except in international interactions or specific educational programs. There are 19 other national languages (Bantu) [59,60] (43 considering dialects [8]), which are spoken daily in informal settings. Local languages include Makwa, Swahili, Yao, Nyanja, Chuabo, Ndau, Sena, Bitonga, Changana, and Ronga.

According to da Câmara [59], the language policy inherited from colonialism disadvantages people who communicate primarily through non-official languages, considered only a cultural and educational heritage to distinguish the population’s identity as Mozambican. According to the author and general knowledge, the Portuguese “assimilated” some natives with their language and culture in late colonialism, distinguishing them as a privileged class.

Figure 3.

Mozambican population (a) per province (Made by the author based on the data from INAGE [61]) and (b) age pyramid (source: PopulationPyramid.net [62], under a Creative Commons license CC BY 3.0 IGO). According to the 2017 General Census, the estimated population is 29,496,008 [63].

Mozambicans are familiar with English because Mozambique is a member of the Commonwealth of Nations [64], all bordering countries are English-speaking, the SNE includes basic English classes from 8th to 12th grade, and there is a high exposure to songs and other multimedia content in English. Most imported products from South Africa have English labels. French is not as frequent but is also present in Mozambique and Spanish is also present due to its similarity with Portuguese and the strong relationship between Mozambique and Cuba and other Spanish-speaking countries. Minor groups speak other European languages such as Italian, Russian, and Deutsche; Asian languages such as Arabic, Hindu, Gujarati, Urdu, and Mandarin; and local languages from Nigeria, Somalia, Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Rwanda [59].

There are matriarchal and patriarchal communities, depending on areas and ethnic groups [18]. The country seems predominantly patriarchal, but the northern provinces are mainly matriarchal [65,66]. Post-independence factors such as migration—especially inter-regional—and interethnic or intertribal marriages probably affect these social systems.

According to Mutiua [67], since the early 1990s, the existing religions have expanded substantially in infrastructure and there have been new congregations or other religious institutions. Table 1 shows that the number of believers between 2007 and 2017 increased, especially the followers of Pentecostal evangelic churches [68,69], with a 2.4% increase. However, the Catholic church suffered a reduction in the percentage of followers. These trends are not surprising, considering their approaches to faith. Pentecostal churches frequently promise prosperity to their followers as a divine reward for their offers to the congregation; such offers are enough to reinvest in their infrastructures and communication channels and attract more followers and resources [70].

Table 1.

Percentage of followers of different religions in Mozambique in 2007 and 2017. Source: Adapted from Mutiua [67].

Regarding Islam, the increased number of followers might relate to the fact that men in Mozambique have to join the religion when marrying a Muslim woman and, consequently, their children are born as Muslims. On the other hand, when the man is Muslim, and the woman is from another religion, she frequently converts or does not prevent the children from being raised as Muslims. Both situations favor the expansion of Islam in Mozambique.

There are also followers and practitioners of local belief systems and spiritual practices. This group is possibly the most diverse because some can simultaneously follow the Judaic-Christian religions. Salite [71] studied farmers’ beliefs in the Gaza province; most seemed to practice or follow cults of nature and ancestors. It is well-known in Mozambique that some people have spiritual beliefs related to animals, such as snakes and some birds, associating them with ancestors or protector spirits for crops or sacred woods [72]. It is hard to know how many people belong to this group for several reasons, including a stigma and fear of traditional spiritual practices, leading some followers not to admit it publicly, and the lack of official congregations or equivalent to represent them. There is AMETRAMO (Association of Mozambican Traditional Healers) [73], but it is a syndicate rather than a religious group. The unfortunate discrimination of the traditional healers prevents the local authorities from harnessing their untapped potential, particularly regarding ethnobotanics [74].

2. Economy, Development, and Poverty

2.1. Political Economy

Despite the abundance of natural resources [1], some authors described Mozambique as low-income, underdeveloped, with an ailing economy [1,15,75], over half the population living in poverty [75], and a weak entrepreneurial and industrial capacity to respond to local demand [75,76]. The country is still defining a suitable market model and the balance with state intervention while managing the scarce financial resources compared with the current stage of the globalized economy; this is a dilemma regarding the country’s development, in which the State needs to strengthen its institutions while promoting privatization, entrepreneurship, and the contribution of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) [33].

Imports and exports are vital to the Mozambican economy. Mozambique imports several essential products for consumption [6]. The country prioritizes exports, with most products going to the Southern African Development Community (SADC) area, Europe, the US [47], and China [76]. Farmers comprise 70% of the population [45]. Agricultural export remained robust, growing annually by 16% on average between 2017 and 2019 [47]. According to Matchaya et al. [77], the country’s foremost producers of maize and other cash crops are the central provinces (Manica, Sofala, Tete, and Zambézia), followed by northern provinces (Nampula, Cabo Delgado, and Niassa). In the south, the Chókwè district is the country’s largest irrigation scheme and a major rice producer in its region, currently harnessing only 35% of its potential for agriculture [78]. Despite the considerable export volume, Betho et al. [79] warned that relying on a narrow range of products causes Mozambique to be vulnerable to fluctuations in the international market.

Currently, a dominant neoliberal policy aims to attract foreign investment for megaprojects and globalize the economy and culture, resulting in social and land inequalities [33]. Cambrão and Julião [18] described Mozambique as a risk society, with the Industrial Revolution and globalization affecting its political, economic, social, technological, and legal environment. According to Fobra and Mavundla [80] and Nuvunga et al. [81], some phenomena, such as the devaluation of metical (the local currency), an increase in interest rate, and inflation, have added to high-profile financial scandals and crises and discouraged investors. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) was among such investors [82].

Unemployment reduced from 20.7% in 2014 to 17.5% in 2020 [9]. About 70–90% of the active Mozambican population works in the informal sector—usually, family businesses [16,83]—or has no defined occupation [18,33,84] and 50% comprise low-income vendors, domestic servants, or building security officers [85]. According to Aliança Moçambicana da Sociedade Civil C-19 [45], 10% of the active population comprises unpaid workers. People move daily from slums to capital cities through overcrowded minibusses to perform subsistence activities [86]. Regarding commerce, it sometimes occurs in farmers’ markets, sometimes door-to-door, and sometimes in the streets [16]. In Maputo and other urban areas, the informal market is vital to curtail the inefficiencies of the formal sector [76,87].

Urbanization is a challenge in Mozambique, as the physical distance between the municipal authorities and slum residents causes governance to be difficult [88,89]. As the country became independent, the new socialist State lead the territorial planning, promoting population expansion around cities, primarily for low-income citizens [90]. The lack of land planning instruments drove the situation increasingly out of control [88]. The citizens living in slums face a lack of land tenure or security [88], vulnerability to leptospirosis and other infectious illnesses [91], overcrowding, substandard housing, poor sanitation and drainage, waste mismanagement, faulty road systems, public spaces, electricity, communications, no access to credit, and other social amenities [88,91]. The slums are occupying an increasing amount of space [91], now 60% of the urban population [88], as people migrate from rural to urban areas. Some examples of slums are the suburban districts of KaMavota, KaMaxakeni, Lhamankulu, and KaMbukwana in Maputo City [91,92]. Some examples in Beira include Macurungo, Manga, and Munhava.

The primary source of income in slums is the informal economy [90,91]. Informal workers lack legal protection, social security, pension, formal funding, or hiring qualified labor [33,45,93,94]. Nevertheless, Mazzolini et al. [87] stated that the informal sector is not ignored or neglected. Around 95% of women practice non-qualified work, primarily subsistence agriculture [47,93]. Informal workers frequently have low purchasing power or savings for a sustainable lifestyle and their income can only ensure a one-day livelihood [76]. Vendors must frequently move, always searching for the best suppliers and clients, generating low and fluctuating income [16].

2.2. Economic Growth and Development

Mozambique is a low-income country [95], among the world’s poorest economies [82], with an average gross domestic product (GDP) per capita of USD 493 [96] in 2020 and USD 503 in 2021 [95], with 60% resulting from the informal sector [83]. The GDP is significantly (40%) generated in informal activities [93] and the sector is expanding [83]. Betho et al. [79] stated that construction, machinery, and transport equipment are the main investment-driving sectors in Mozambique, but mining is among the most influential, with some already established companies and others still building their plants.

From 1996 to 2001, the country had a sustained 8% annual economic growth; from 2002 to 2015, it stabilized at 4–5%, and from the second half of 2015, the growth started to slow down [82]. The period of steady growth, considered among the continent’s best economic performances, resulted primarily from the mining, metal processing, and energy industries [76,82] and critical companies include Mozal, Sasol, and Vale do Rio Doce. Mozal is an industrial complex with an aluminum refinery as its primary activity [97]. This company is the country’s first megaproject based on foreign investment, paving the way for others to finance mining and other sectors. Sasol extracts and exports natural gas from Pande and Temane districts to South Africa [98], the Brazilian company Vale do Rio Doce explored mineral coal for some time [99], and other megaprojects intend to explore liquid natural gas in the Palma district, Cabo Delgado province [1,100,101]. Daly [102] predicts that Mozambique’s economy will increasingly rely on exploring Cabo Delgado’s gas and Salvucci and Tarp [82] add that if the country establishes its total capacity to explore the liquid gas and coal reserves found in the early 2010s, the country’s wealth will increase exponentially.

Tourism is another strategic area for the country’s development, partially due to its contribution to the economy and potential for growth [1]. Recent discouraging events, such as warfare and inflation, certainly discourage tourism, which is a fact notable for the decreasing number of international and local tourists since 2014 [103]. However, the country’s natural resources and cultural heritage are a “fertile ground” for investment, generating employment, and a stimulus to other sectors (e.g., transport and communication), thus alleviating poverty [1]. As the pandemic entered Mozambique, the country had 2462 hotel facilities, 3986 bars, and 336 travel agencies, in total employing approximately 64 thousand people [1]. However, there is a need to decentralize tourism, as Maputo City has 35% of all the country’s hotel facilities [101]. Some destinations, such as the Gorongosa National Park, are thriving and showing how tourism in Mozambique can have a global impact, even after the 16-year war and other minor armed conflicts in the area [104,105].

2.3. Poverty

Several surveys allowed an understanding of poverty trends in Mozambique [82]. Mozambique has a high poverty rate [17,79] and reducing it is among the country’s challenges [106], but it has not been easy [33], as the cost of living keeps increasing [83]. People living below the poverty line (USD 1.90, according to The World Bank Group [107]) decreased from 69.4% (1996–1997) to 53% (2002–2003), 52% (2008–2009), and 46% (2014–2015) [47,82,108]. Nuvunga et al. [81] estimated the pre-COVID-19 poverty rate to be 41–46% (from 10.5 to 11.3 million people), but Aly and Alar [109] presented contrasting and less optimistic information, suggesting that since 2016 the poverty rate might have risen to 55–60% due to a crisis and high inflation following a financial scandal and loss of investors, warfare, and natural calamities (to be further discussed in Section 6). Other sources support the latter authors and agree that more than 50% of Mozambicans live with less than USD 1.00 daily, often earned through informal work [45,47]. Among the people living in poverty, 10 million are children [109].

Few people in poverty can improve their situation and some intermittently move in and out of poverty, primarily due to the alternate dry and rainy seasons [82]. The average income can barely ensure subsistence, with 42.5% of the population living in food insecurity [33,45,110], with unpredictable daily income [33]. Furthermore, the number of poor people between 2009 and 2015 increased by 700,000 individuals due to population growth [108]. The prevalence of undernutrition is 27.9% [110], particularly in the most impoverished rural areas [33]. Around 43% of Mozambican children have chronic undernutrition [111].

Nuvunga et al. [81] described the social support policy in Mozambique. According to them, the country has the National Basic Social Security Strategy (ENSSB) and related multisectoral plans enforced by the National Institute of Social Security (INSS), National Institute of Social Action (INAS), and other institutions. It is part of ENSSB to allocate 2.23% of the GDP to social protection for at least 28% of vulnerable households. Most of these target households are in rural areas [67]. There is also support from non-governmental organizations to alleviate poverty and stimulate development [112].

Multidimensional poverty is stagnating or worsening [82] and it is more prevalent in the country’s central and northern areas [47,82,93], ironically the most productive [77], due to the historically strong centralization of economic power in the south, especially in Maputo City and the homonymous province [81]. It is challenging to distribute food to the population [15], particularly in the southern provinces, with less local production and a high reliance on imports from South Africa [33,45].

As the economy improved, between 2008–2009 and 2014–2015, the Gini increased from 0.42 to 0.47, i.e., consumption inequality increased significantly [82]. There is also a weak inclusion to reduce structural inequalities between cities and rural areas or between the capital and the provinces [81]. Inequality is visible, even within an area, particularly in urban settings. In Maputo, for example, there is an area with tall buildings, large houses, and tarred roads inherited from the colonial era, contrasting with densely inhabited slums with precarious or unfinished constructions [86,113]. Besides inequality, regional disparities, and natural disasters, poverty also results from low agricultural productivity compared to other parts of the world [82].

Access to clean water and electricity are also challenges [18,114]. Approximately 17% of the urban population and 48–52% of rural people have clean water [33,45]. Most refugees from the conflict in Cabo Delgado, crowding in camps and houses, cannot access clean water [115]. Nearly 22.2% of the Mozambican population (including 26% of the children) have electricity [33,75] and the remaining must rely on batteries (41.1%), firewood (12.2%), oil derivatives (7.6%), candles (4%), or other energy sources (3.9%) [116]. Solar energy is also becoming popular [17].

3. Education, Human Development, and Science

3.1. Preschool to High School Education and Human Development

Culimua and de Figueiredo [3] and Teixeira et al. [17] comprehensively overview Mozambique’s National Educational System (SNE) and the following description is a synthesis of both sources. According to them, SNE started “from scratch” as the country became independent (in 1975) due to the need to reform the strongly segregated system of the Portuguese colonialists. The priority was to decolonize people’s mentality, promoting the sense of freedom and sovereignty. By then, 98% of the population were illiterate. The government introduced the first autonomous SNE through the law 4/83 of 23 March 1983, massifying education as an equal right of all citizens. The priority was to ensure social cohesion and national unity without considering sociocultural differences.

According to Teixeira et al. [17], SNE went through three stages: (1) just after the independence until the early 1980s, when the main focus was educating adults to improve the workforce; (2) during the climax of the post-independence civil war, late 1980s and early 1990s, in which the country’s destabilization resulted in the discontinuation of educational programs; and (3) after the Peace Treaty and first democratic elections (in 1994), with remarkable improvements of the entire educational system.

The Ministry of Education and Human Development (MINEDH) administrates the SNE. The general SNE subsystem comprises preschool education (to support the parents’ educations), first-degree (5 years) and second-degree (2 years) primary levels, basic secondary level (3 years), and pre-university (2 years) before higher education. SNE aims to develop and consolidate the students’ skills in communication, natural and social sciences, mathematics, and practical and technological activities [3,30]. Such skills are essential to join higher education.

There are other components of SNE. The Technical and Professional Education (ETP) subsystem is also part of the government’s developmental strategy [117], which is aimed at people intending to join the workforce or improve their skills without necessarily joining higher education. SNE includes adult education, teachers’ training, and higher education [30]. A critical supplement of SNE is extracurricular education, which includes nonrequired but advantageous competencies such as sports and performing arts [3].

Most public educational facilities do not present the desirable quality [17,112], but education and literacy are fundamental rights and development priorities [17]. Nearly 8.3 million people pursue the primary and secondary levels in all provinces [18,109]. The government offers primary education for free [3,109] and the cost of secondary education per student is USD 9.43–11.78 annually, a cost usually covered by parents in the case of young students [109]. District Administrators encourage schools to alleviate their financial constraints and support students in hardships through strategic partnerships, but such collaborations are rare [112].

Some issues are still to be overcome in education, such as high dropout levels, illiteracy, and low student success rate [118]. The dropout rate before the third grade is over 33.3% and more than 50% of students quit school before completing the elementary level [30,119]. Approximately 47.2% of people of school age are not studying and the situation worsens as people age, especially in rural areas and women, who frequently drop out due to early marriages [17]. Furthermore, there is significant educational inequality, as a privileged group has access to high-quality educational standards while the majority study under high-quantity–low-quality standards [3]. Such differences can result in a vicious circle and significantly increase the intellectual gap between people from distinct social classes.

According to Vasco [15] and Lázaro and Fontana [116], Mozambique’s human development is unsatisfactory. According to the 2017 national Census, 47.2% of the 22,243,373 people above five years old were illiterate, 51.6% literate, and the remaining 1.2% were in an unclear situation [17,120,121]; 57% live in rural areas [120]. There are substantial disparities in physical or financial access to education, socially and geographically [3]. Over 95% of third-graders could adequately read and write, 26% of 5–12-year-old children were not studying and 68% of 12–13-year-olds were still in elementary schools [109].

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the Ministry of Education and Human Development (MINEDH) and its partners struggled to ensure the studies of victims of natural disasters, providing temporary study shelters [119]. Matsinhe [122] stated that the Ministry of Education received 77% of the expected 1,500,000 new enrollments in elementary schools. Furthermore, the government built 4526 classrooms between 2016 and 2019. Unfortunately, warfare and natural disasters destroyed 7322 classrooms, seriously compromising the investment.

3.2. Science, Technology, and Higher Education

Science and technology in Mozambique are emerging. The country promotes science through several initiatives and partnerships, mainly from research centers and higher education institutions. There seems to be a strong political will for innovation; one good example is the intention of Eduardo Mondlane University (UEM), the country’s oldest, to become focused on research [123]. Dominant research areas in Mozambique strategically focus on the country’s development and some examples are agriculture, health, fisheries, environment, and African studies. Unfortunately, in practical terms, most research in Mozambique does not seek innovation. In other words, instead of developing products, services, or methods, most studies aim to register, catalog, or assess phenomena with existing methods or tools, usually imported. At the moment, such a paradigm seems to be part of what the country needs to create for the foundations of a coherent and sustainable countrywide scientific enterprise.

It is well-known that information technologies worldwide are increasingly affordable and improving in functionality and their impact in virtually all sectors of activities is remarkable. Similar to most developing countries, Mozambique imports technology and the people, especially younger generations, are becoming progressively more technologically literate. However, the situation is still far from desirable, as only 4.4% of Mozambicans have computers and 6.6% have access to the internet [75]. Other fields, such as biotechnology, molecular biology, precision agriculture, aquaculture, or other advanced scientific subjects, are gaining attention in academic circles [124,125,126].

It would be reasonable to discuss higher education in the previous section. However, in Mozambique, this subcategory of education is under the tutelage of the Ministry of Science and Technology and Higher Education (MCTES), perhaps because the government intends to cause them to be more research driven. MCTES is new compared to most homologous initiatives, as the President of the Republic created it on 17 January 2000 [127], and a special committee reformed it on 21 January 2021 [128]. MCTES is responsible for universities, academies, higher education institutions, the National Research Fund (FNI), several research institutes, and other academic or scientific organizations.

Higher education used to be scarce in Mozambique. Until 1994, there were only three institutions (all public), all in Maputo City, and by 2014 there were 46 (18 public and 28 private) [129]. At the end of 2020, 22 public and 31 private higher education institutions totaled 53 [130]. The public comprised nine universities, eight higher institutes, two tertiary schools, and three academies [30]. According to Uacane and Pego [131], the number increased to 54 in 2021. The number keeps rising because the government promotes education, research, and entrepreneurship [132]. The country’s southern region, particularly the capital, still has most institutions for tertiary education [131], but there is an increasing degree of decentralization. The institutions dedicated to higher education differ substantially in quality, facilities, lecturers’ skills (e.g., computer literacy), and expertise [131].

Similar to virtually everywhere else, Mozambique seems receptive to distance education, particularly online [131,133]. Several institutions, especially higher education, are starting to share educational content through specialized platforms such as Moodle and resources such as the Mozambican Research and Education Network (MoRENet) [75,131]. Still, the study by Uacane and Pego [131] at Licungo University (UniLicungo) revealed that its academic community barely used laptops, desktops, or tablets, although 89.1% had cell phones. Furthermore, the researchers did not explain the generation of such phones, though this aspect is a crucial pertinent negative to assess the situation further, considering that the large majority carries these devices. Still, one must assume that the authors were informed enough to know that most were not smartphones, leading them to say there was a weak IT culture in the university, worsened by a lack of training in digital platforms. This issue is not specific to that institution, as personal computers and access to the internet are scarce in Mozambique [75,116]. At UniLicungo, most people (78.9%) who benefited from any computer looked up to it and manifested the desire to continue using it.

4. The Healthcare System and the Burden of Disease

4.1. The National Healthcare System

The Ministry of Health has chosen to pursue the goal of universal health coverage [8], particularly between 2006 and 2016, by modernizing the service, introducing services such as e-Health, and strengthening medical teams, with support from European and North American governments and NGOs and international agencies [33]. E-Health, adopted in 2017 by the National Health Service (SNS), now focuses on training professionals and exchanging experiences with other countries [134]. Still, 95% of health facilities are primary centers, the only alternative in rural areas [8], and limited access to health care is an obstacle to obtaining health as a human right [83].

National health policies are becoming neoliberal [33], but significant challenges are ahead, as SNS is under-resourced [95], with a shortage of infrastructure and medical equipment [47,83] and limited access to other essential facilities such as clean water and hygiene [6]. Some authors describe Mozambique’s healthcare system as prevailingly weak [47,95,111,135] and heavily reliant on foreign donors [8], although access to health is virtually free, with consultation costing approximately USD 0.016 and medication costing USD 0.079 [109]. It looks “good on paper,” but there are significant challenges regarding access to healthcare, especially in rural areas and the country’s northern provinces [8]. For instance, the average distance for a patient to reach the nearest healthcare unit is 15.2 km in the Niassa province, a distance below the 8 km recommended by WHO [136]. Nearly 66.9% of the population needs one hour by car to reach a primary healthcare unit [8]. On average, for every 10,000 residents, there are seven hospital beds, with 41% of those beds reserved for maternal care [95].

Qualified human resources are scarce in several healthcare units [33,134]. Mozambique has 77 health professionals (nine physicians) per 100,000 inhabitants [95,137]. From 2006 to 2012, the number of physicians increased from 606 to 1722, most working as general clinicians in the public sector [33]. Many district capitals only have nurses in the healthcare units, often working in the daytime only because most districts have limited access to electricity or tap water [86]. Furthermore, most healthcare professionals have limited training in disease research and control [47,83].

4.2. The Burden of Disease

Giordani et al. [84] said that Mozambique still needs to strengthen its capacity to control well-known maladies such as malaria and cholera. There are significant disparities between urban and rural areas [114]. The limited waste and sewage management capacity and deficient water distribution systems worsen the country’s situation by enabling the dissemination of hygiene-related comorbidities [33,95].

Traditional medicine is the primary healthcare for nearly 60% of the population in Mozambique, causing healers to be a pivotal component of the country’s healthcare system [110]. The Mozambican Traditional Physicians’ Association (AMETRAMO) works with the Ministry of Health (MISAU) to regulate traditional healing and harness the country’s biodiversity for the sake of the population’s well-being [138,139]. Hlashwayo et al. [110] added that 10–15% of the national flora’s 5500 plant species have medicinal applications.

Mozambique has a cumulative burden of infectious and chronic maladies [95], frequently resulting from poverty, limited access to clean water, and a flawed health system [8]. The country’s leading causes of death are HIV/AIDS, neonatal disorders, tuberculosis, malaria, stroke, lower respiratory infections, diarrheal diseases, ischemic heart disease, congenital disabilities, and road injuries [140,141]. These issues, particularly HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis, significantly shorten life expectancy at birth, attracting donor-funded initiatives [8].

Malaria is endemic, partially due to the country’s rainy tropical climate. The prevalence is high and responsible for 29% of hospital deaths in general and 42% of infant (<5-year) deaths [95].

HIV/AIDS is particularly relevant because Mozambique is among the most affected countries worldwide, with an approximated prevalence among people aged 15–49 years of 11.5% [4,33] reported in 2020 and 13.2% reported in 2022 [95]. Mozambique presented the world’s eighth highest malaria incidence in 2018, with a high case fatality rate [10].

Mozambique is among the 20 countries with the highest tuberculosis incidence, with 361 cases per 100,000 people in 2019, reflecting the 110,000 new cases that year [142]. Tuberculosis and its sequelae are among the diseases associated with pneumonia in the Central Hospital of Maputo, the others being asthma and bacterial infections [143]. Furthermore, 38% of HIV-infected patients have tuberculosis [95].

In September 2020, there were 17 thousand pregnant women and there was a prediction of 4700 newborns with complications and the need for pediatric care [144]. Infant and maternal death are also common [33], frequently due to infectious diseases, anemia, or undernourishment [145,146,147]. There are strategic programs to promote maternal and neonatal health [33]. According to Chimbutane et al. [148], anemia among rural 0–5-year-old children was 49.5% in 2018.

Non-communicable diseases are highly prevalent among young adults [95]. According to Sumbana et al. [55], a recent survey indicated that hypertension, diabetes, and other non-communicable diseases were responsible for 28% of deaths in Mozambique. Currently, obesity is 11.5% prevalent in urban areas and 2.6% in rural areas, higher in women (6.2%) than men (2.3%). The authors added that the prevalence of non-communicable diseases in Mozambique is increasing, potentially causing the population to be more susceptible to COVID-19. This information is vital because COVID-19 seems severe for people with non-communicable diseases [149].

At least once in a lifetime, the ordinary Mozambican citizen expects exposure to measles, tetanus, or other infectious diseases, which is why Mozambique started the National Immunization Program soon after its independence in 1975 [4,10]. All pregnant women receive a vaccine for tetanus (TT) and children receive the pentavalent DPT-HepB-Hib to prevent diphtheria, hepatitis B, Haemophilus influenza type B, pertussis, and tetanus; they also received the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV), bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) for tuberculosis, and oral polio vaccine (OPV). Furthermore, several campaigns have promoted adherence to healthcare, immunization, pre-natal consultation, and treatment of endemic diseases [150]. According to Martins et al. [10], Mozambique has the widest age range of BCG-vaccinated people in Africa because, between 1976 and 1978, all children and adolescents below 15 years old [34], 97% of the country’s population, and 99% of people living in Maputo City received the vaccine. The same authors stated that the 16-year civil war was more detrimental in rural areas, substantially reducing vaccine coverage.

5. International Relations and Diplomacy

5.1. Diplomatic Profile

After its independence, Mozambique worked on the institutional consolidation of its foreign affairs, focusing on constructing its sovereignty, and FRELIMO has been the leading party for approximately all along, leading some people to confound it with the State [151]. Most initial efforts to build the nation were unsuccessful due to warfare [152]. There is some effort for decentralization, as the Council of Ministers [153] ratified Decree 2/2020 on 8 January.

Mozambique’s internal diplomacy is based on the western democratic model, aiming for regional economic development [154], peace, democracy, political stability, security, and the reduction in poverty [152]. Currently, the country is diplomatically proactive, primarily by exerting soft power [40,155] through intercultural relations, collaborating with NGOs and other governments to tackle development challenges, and offering investment opportunities to multinationals. The country uses culture irregularly to approach other nations through cooperation agreements, but it is implicit within the main goals of the country’s foreign affairs [155]. Regarding megaprojects, the country made the highest effort to attract them between 1987 and 2005 and several are now well-established [154].

To understand how Mozambique interacts with other countries, it is crucial to consider how several dimensions, such as internal, regional, and international, are all connected and influencing each other [40].

5.2. Domestic Affairs

Regarding internal affairs, the country is initially a nation-state with the common goal of defining its identity after the burden of colonialism, then combatting the rebels during the civil war [40]. Samora Machel’s government was nationalist and Marxist–Leninist with a State-party, regarding RENAMO as an enemy. The main challenge was to build the State and centralize the political authority [151].

Joaquim Chissano introduced a model of external affairs featuring the abandonment of communism, opening the country’s economy to a free market [154]. With the multiparty democratic regime, internal affairs and state sovereignty still determine the country’s foreign policy [151]. Mozambique envisions sustainable development with particular attention to mitigating poverty and related issues [40].

5.3. African Relations

Mozambique belongs to Southern Africa, although by its location, some might consider the country as part of East Africa. As the country became independent, it started consolidating development goals and political relations with the surrounding countries [152]. Mozambique was a Frontline State (FLS) (against Apartheid) and a founding member of the Southern Africa Development Coordination Conference (SADCC), now known as the Southern African Development Community (SADC) [40,152,156]. The latter has longstanding history of mutual support among the members in several matters. Such support can be from political and military, economic, transport and communications, and many other sectors. Such a relationship with the surrounding countries firmly molded Mozambican diplomacy [151].

Mozambique is also a member of the African Union (AU) [156] (formerly Organisation de l’Unité Africaine [French] or OUA), an African intergovernmental organization founded on 25 May 1963 to promote peace, security, and development of its 55 member States [157]. As an active member, Mozambique has led several AU initiatives, including hosting the African Union Conference of Ministers of Health, in Maputo City, between 18 and 22 September 2006, on Repositioning Family Planning to Reduce Unmet Need [158].

5.4. Global Relations

Internationally, Mozambique initially opted for non-alignment and developed activism against colonial exploitation and Apartheid [40]. When the Cold War and Apartheid ended, the focus changed to collaboration in several other causes. During the entire period to establish peace between FRELIMO and RENAMO, the United Nations (UN) sent a mission called ONUMOZ (United Nations Operations in Mozambique), functioning between 1992 and under Security Council Resolution 797, to coordinate the implementation of the Rome Peace Treaty [159]. Besides, the country is a member of several UN organizations and, on 1 January 2023, Mozambique will be a non-permanent member for two years [160].

Mozambique is a member of the Community of Portuguese-Speaking Countries (CPLP) and an observer of the Commonwealth of Nations, and Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie, besides participating in several other multilateral and bilateral agreements and organizations. Such engagement in international relations opens several opportunities for businesses, students, and the public sector. They also allow the country to receive support when needed. For instance, CPLP allowed Mozambique to support East Timor when the country needed independence from Indonesia and East Timor to help Mozambique when cyclone Idai occurred [161]. On the other hand, international platforms facilitate networking and establishing channels to share the country’s goods.

5.5. Overall Impact

International relations and diplomacy are an integral part of Mozambique’s governance. The country’s liberal political posture significantly increased the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), especially in the late 1990s and early 2000s, mainly due to the emergence of mining to channel raw materials abroad, but there was little sustainable development [151]. Wasse [154] added that megaprojects to restructure the economy were ineffective due to poor execution. On the other hand, participation in international organizations allows Mozambique to expand its cultural heritage abroad through festivals, artist exchange events, and cooperation, thus contributing to the consolidation of the African identity [156].

5.6. Comments

In line with the idea of Júnior [156], it seems reasonable to consider that Mozambique should harness more of its cultural wealth, expanding it abroad as a component of its soft power to obtain more attention from potential partners in several sectors. Perhaps the country should follow the example of small countries such as Jamaica and other Caribbeans or Cape Verde, with a strong presence in the international arena, even with relatively small portions of land and a reduced population.

6. Zeitgeist: “The Perfect Storm” in Mozambique

COVID-19 did not find Mozambique in its best shape [6,30]. The country already had a history of destruction due to the post-independence civil war (1977–1992) [82] and floods in 1995 and 2000 [33,74]. As COVID-19 arrived, Mozambique faced multiple crises slowing down the economy and degenerating the living standards [81,82]: economic crisis due to an unsustainable hidden debt [7,81,162], armed conflicts [33,76,103], recovery from natural disasters [33,76,79], and related outbreaks of infectious diseases [33]. Thus, the political, economic, and social environment was unfavorable to receive one more calamity. Furthermore, there was a widespread panic due to the country’s discouraging environment, added to the tremendous misinformation through social media and sensationalist press, besides the statistics of COVID-19 dissemination and related death rates published. Hanlon [163] described war, natural disasters, and COVID-19 as triplo flagelo [triple scourge, in Portuguese]. Thus, adding the economic crisis to the equation, Mozambique faces a quadruple scourge, increasing the poverty rate [79].

The flood in 2000 in the country’s south still impacts the economy, mainly because Mozambique lost touristic infrastructures or means to access them and the supply of crucial resources such as water or electricity [1]. It is true that much has been recovered or even improved from the situation before the flood, but one can only imagine how things would have been if the country did not face the calamity and kept the economic growth witnessed in the late 1990s early 2000s [164].

Manuel Chang, a former Minister of Finance, and other government officials orchestrated an illegal scheme to obtain over USD 800 million from international banks [165,166], later found out to be more than USD 2,7 billion [167], resulting in the so-called dívida oculta [“hidden debt,” in Portuguese] [111,162,168], with the name sometimes attenuated by the mainstream media to dívidas não-declaradas [“undeclared debts,” in Portuguese] [167]. The information leaked in 2016 caused panic and public mistrust of the government, leading partners to withdraw their support and negatively impacting the economy [81,111]. The case remains unresolved as this manuscript is under preparation [167] and there is no prospect of a short-term resolution [81].

The Cabo Delgado province is facing military and humanitarian crises due to terrorism [1,81]. The districts of Mocímboa da Praia, Macomia, Muidumbe, and Quissanga districts are under armed attacks by the so-called Al-Sunnah wa Jamo (ASWJ) Islamist-linked insurgents, with unclear motivations [41,115,136] since October 2017, thus threatening the national security in the region [18,41,102]. Some sources associate the perpetrators with Al-Shabaab [94,115,163], the jihadist fundamentalist group [169], and according to Daly [102], in 2019, the perpetrators claimed affiliation with the Islamic State. The battle, comprising more than 600 attacks [83], caused more than 2100 deaths (more than 60% civilians), displaced approximately 355,000 people (13% of the population) by mid-2020 [83,115], and caused infrastructure loss, besides the proliferation of waterborne disease, as displaced people frequently settled in unsanitary conditions [94,102,115]. By 19 October 2020, there were 424,202 displaced [83] and, by mid-2021, the number had risen to nearly 530,000 [81]. More recent estimations indicate the displacement of approximately 700,000 people, which is still increasing [83]. Some infrastructure destroyed included 20 health facilities, schools, houses, and government properties [115]. Aliança Moçambicana da Sociedade Civil C-19 [45] mentioned attacks also in the Nampula province.

ASWJ is becoming more lethal and sophisticated and the attacks have become more frequent, with tactics to promote government mistrust [102]. The Lancet mentioned horrifying brutality in the Muidumbe district [115]. Chingotuane et al. [170] added an example of 23 March 2020, when the group invaded the town of Mocímboa da Praia, defeated the local Defense and Security Forces, and raised their black flag. It might have been a symbolic act because the same source mentioned that the insurgents remained there for hours and left voluntarily without any intervention from the Defense and Security Forces. In mid-August 2020, ASJM took over the port and city of Mocímboa da Praia again [102]. The government and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) provided shelters for 10,000 refugees in Pemba city, with similar initiatives throughout the country [115]. Several entities have been visiting Cabo Delgado to support the refugees [1,101].

The warfare might sabotage the recently established projects to explore natural gas in the Rovuma River Basin [33,109], discovered in the early 2010s [33]. For instance, Mocímboa da Praia is 90 km south of the Palma district’s international megaprojects for natural gas prospection and extraction [1,170]. Such gas reserves, capable of increasing Mozambique’s GDP sevenfold in 25 years [102], attracted large corporations such as Exxon-Mobil Corp. and Total SE [170].

Sofala and Manica provinces were also under political instability since mid-2019 due to a group led by Mariano Nhongo, a self-proclaimed Renamo Military Joint [41,83], responsible for several guerrilla attacks [170,171,172]. This conflict was due to internal disagreement between leaders of the Renamo political party after the death of the long-lasting President, Afonso Dhlakama [172]. The Military Joint is causing uneasiness and fear to residents and visitors in some districts of the provinces affected [170].

Just before Mozambique presented the first confirmed case of COVID-19, almost all the countries, including all the surroundings, already had cases [7,173]. Most people were probably mentally prepared to face the pandemic within the national borders due to the widespread panic through social media [18], pessimistic predictions from British scientists [174,175], and discouraging information such as the GHSI assessment ranking Mozambique 153rd out of 195 countries regarding pandemic response capability [176]. Additionally, if the pandemic was virtually everywhere by mid-March 2020, why would Mozambique be any different?

Recent intense tropical storms hit roughly the same areas of armed conflicts (Cabo Delgado and Sofala provinces) plus Manica, Tete, Zambézia, and Nampula [18,33,76,109]. The threat of tropical storms seems regular, occurring yearly [103], usually between January and April. The cyclones Idai [177] and Kenneth [115,178] in 2019 were responsible for the most damage, but the tropical storms known as Chalane [179] and Eloise [180] also caused significant losses. It is still difficult to reach part of the population due to the destruction by the cyclones [79]. Table 2 shows some of the losses. There might be a direct relationship between the number of people displaced and the storm’s magnitude, as the events directly affected the infrastructure. The population is higher in the north of Mozambique, mainly in the Nampula province, where cyclone Kenneth hit. Kenneth is among the strongest storms recorded in African history [178].

Table 2.

Losses due to the recent tropical storms in Mozambique.

The number of deaths reduced as time passed, with Idai (in Sofala province) showing the highest number of deceased and perhaps the highest destruction of houses, infrastructure, and commercial assets [81]. For Chalane and Eloise, the decrease in deaths might be due to their low magnitude, but Idai and Kenneth differed, probably due to their timing. Idai was the first event when the country was generally less prepared for tropical storms.

Mozambique had several floods, particularly in the south (Chókwè district) [181], but tropical cyclones were less frequent. After Idai, the United Nations updated the 2018–2019 Mozambique Humanitarian Response Plan [182] and it was a good starting point to respond to Kenneth two months later. A similar work followed cyclone Kenneth [183], combined with the Early Warning, Alert, and Response System (EWARS) [178], and other post-cyclone initiatives might also be the reasons for a more effective response to the Chalane and Eloise tropical storms.

The sources in Table 1 mentioned infrastructure losses potentially affecting the country’s capacity to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, cyclone Kenneth alone destroyed 19 health facilities in northern Mozambique [178], worsening the already limited access to healthcare services [109]. In addition, Aly and Alar [109] added that the storms weakened the entire economic activity by disturbing the main ports and several businesses. Krauss et al. [184] believe that environmental factors will increasingly impact people’s livelihoods.

7. Conclusive Remarks

Post-independence Mozambique completes 50 years in 2025, the country being understandably in an informed trial-and-error process of nation-building. For instance, the government published the most recent revision of the Constitution in 2018 [46]. In some aspects, the country shows the developmental pattern of several other countries of the Global South, including some constraints such as corruption. Mozambique still faces the infrastructural and socioeconomic consequences of the 16-year civil war, contrasting with the 1989 Program for Social and Economic Rehabilitation investment opportunities [185]. The country’s situation is becoming increasingly complex due to natural calamities, disease outbreaks, conflicts, the discovery of natural resources, scandals, government decisions, and globalization. Despite its cultural and historical uniqueness, Mozambique has plenty to learn from countries that have gone through similar experiences.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data on Mozambican population growth from 1975 to 2021 is available on the World Bank Group (https://data.worldbank.org/country/mozambique?view=chart, accessed on 4 October 2022) and World Population Prospects (http://data.un.org/Data.aspx?d=PopDiv&f=variableID%3a12, accessed on 4 October 2022) websites.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Guambe, J.J.J.; da Silva, J.J.; Victor, R.B.; Azevedo, H.A.M.d.A.; Chundo, D.M.I.; Gerente, B.J. COVID-19, Transporte Aéreo e Turismo em Moçambique. Geo. UERJ 2021, e61344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhamona, E.; Manjate, T. O provérbio e a retórica da prevenção contra a COVID-19 durante o estado de emergência nas cidades de Maputo e da Matola (Moçambique). In Ensaios Interdisciplinares em Humanidades; da Silva Filho, A.V., Subuhana, C., de Mello, I.M., de Carvalho, R.O., de Oliveira, M.R.D., Eds.; Editora Autografia Edição e Comunicação Ltda.: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2020; Volume 4, pp. 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Culimua, A.S.; de Figueiredo, S.L.F. O ensino secundário e o recurso às TICs em tempos da COVID-19 em Moçambique. In Proceedings of the VII Congresso Nacional da Educação, Campina Grande, Brazil, 2–4 December 2021; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Cambaza, E.M. The African miracle: Why COVID-19 seems to spread slowly in Sub-Saharan Africa. Rev. Cient. UEM Sér. Ciênc. Bioméd. Saúde Pública 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambaza, E.M.; Viegas, G.C.; Cambaza, C.M. Potential impact of temperature and atmospheric pressure on the number of cases of COVID-19 in Mozambique, Southern Africa. J. Public Health Epidemiol. 2020, 12, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langa, E.S.; Massuanganhe, J.A.; Nhanala, G.A. O impacto do coronavírus (COVID-19) e as mudanças climáticas na taxa de câmbio: Abordagem multivariada para Moçambique. Prometeica-Rev. De Filos. Y Cienc. 2022, 210–226. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/8579728.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2022). [CrossRef]

- Nyusi, F.J. Comunicação à Nação de Sua Excelência Filipe Jacinto Nyusi, Presidente da República de Moçambique, Sobre a Situação da Pandemia do Corona Vírus—COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.presidencia.gov.mz/por/content/download/9052/64281/version/1/file/Comunica%C3%A7%C3%A3o+%C3%A0+Na%C3%A7%C3%A3o+-+16.07.2020.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Denhard, L.; Kaviany, P.; Chicumbe, S.; Muianga, C.; Laisse, G.; Aune, K.; Sheffel, A. How prepared is Mozambique to treat COVID-19 patients? A new approach for estimating oxygen service availability, oxygen treatment capacity, and population access to oxygen-ready treatment facilities. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, C.R.; da Silva, S.R. Práticas de consumo de smartphones no contexto de pandemia de COVID-19: Um olhar etnográfico para as apropriações das mulheres de Maputo–Moçambique Smartphone consumption practices in the context. Comun. Mídia E Consumo 2022, 19, 148–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, H.F.B.; Loquiha, O.; Hansine, R.; Macicame, I.; Maure, G.A.; Marrufo, T.J.; Sacarlal, J.; Abacassamo, F.; Mucavele, H.; Saúte, F.C.M. COVID-19 morbidity and case fatality rate: An analysis of possible confounding factors. J. Infect Dis. 2020, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambaza, E. Influence of population density and access to sanitation on Covid-19 in Mozambique. Ang. J. Health Sci. 2021, 2, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uamusse, M.M.; Aljaradin, M.; Nilsson, E.; Persson, K.M. Climate Change observations into Hydropower in Mozambique. Energy Procedia 2017, 138, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Classic Portfolio. Seasons: Mozambique—When to Go & What to Pack. Available online: http://www.classic-portfolio.com/PDF_Documents/Clients/Mozambique/SEASONS%20-%20MOZAMBIQUE.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- Ducrot, R.; Leite, M.; Gentil, C.; Bouarfa, S.; Rollin, D.; Famba, S. Strengthening the capacity of irrigation schemes to cope with flood through improved maintenance: A collaborative approach to analySe the case of Chókwè, Mozambique. Irrig. Drain. 2018, 69, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasco, S.A.J. Aplicabilidade do marketing digital como meio de promoção do marketing social em meio à pandemia da covid-19 no contexto moçambicano. Rev. Cient. UEM Sér. Ciênc. Bioméd. Saúde Pública 2021. Available online: http://www.revistacientifica.uem.mz/revista/index.php/cbsp/article/view/24 (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Frederico, M.; Matsinhe, C. Resistência à Adopção das Medidas de Prevenção da COVID-19 em Moçambique; Centro de Estudos Africanos, Universidade Eduardo Mondlane: Maputo, Mozambique, 2020; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, R.A.G.; Gonçalves, A.C.P.; Jorge, A.N. Educação remota no contexto da COVID-19 em Moçambique: Um olhar sobre as condições de acesso: Um olhar sobre as condições de acesso. SciELO Prepr. 2022. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1590/SciELOPreprints.4193 (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Cambrão, P.; Julião, D. COVID-19 and its Implications in Mozambique: An Anthropo-sociological Analysis. Rev. Electrónica Investig. E Desenvolv. 2020, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ki-Zerbo, J. (Ed.) História Geral da Africa: Metodologia e Pré-História da África. UNESCO: Brasília, Brazil, 2010; Volume 1, p. 990. [Google Scholar]

- Times, P.I. The East African Coast: An Historical and Archaeological Review. In An Economic History of Tropical Africa, 1st ed.; Konczacki, Z.A., Konczacki, J.M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1977; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Vertriest, W.; Saeseaw, S. A Decade of Ruby from Mozambique: A Review. Gems Gemol. 2019, 55, 162–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J. Adamastorying Mozambique: “Ualalapi” and “Os Lusíadas”. Luso-Braz. Rev. 2000, 37, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Evers, T. Iron Age Trade in the Eastern Transvaal, South Africa. S. Afr. Archaeol. Bull. 1974, 29, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, D.P. Ethno-History of the Empire of Mutapa. Problems and Methods. In The Historian in Tropical Africa; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 105–126. [Google Scholar]

- Liesegang, G. The 17th–19th Century Zimunye Tradition and 19th Century Nguni Empire Archaeology in Mozambique. Stud. Afr. Past 2019, 6. Available online: https://sap.udsm.ac.tz/index.php/sap/article/view/93 (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Idejiora-Kalu, N. Understanding the effects of the resolutions of the 1884–85 Berlin Conference to Africa’s Development and Euro-Africa relations. Prague Pap. Hist. Int. Relat. 2019, 2, 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Edgar, C. A glance at Mozambican dairy research. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2018, 13, 2945–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, D.L. Joaquim Mouzinho de Albuquerque (1855–1902) ea política do colonialismo. Anal. Soc. 1980, 16, 295–318. [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães, J.P. Trajetórias e Resistências de Mulheres sob o Colonialismo Português (Sul de Moçambique, XX); Universidade de São Paulo: São Paulo, Brazil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zeca, K.S.H.X. A Capacidade Estatal e as demandas da sociedade no contexto da COVID-19 no setor da educação em Moçambique. Conjunt. Austral 2021, 12, 07–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamunda, T. In Defence of White Rule in Southern Africa: Portuguese–Rhodesian Economic Relations to 1974. South Afr. Hist. J. 2019, 71, 394–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhart, G. Independence comes to Mozambique. Afr. Today 1975, 22, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva, C.A.; Monie, F.; Mulhaisse, R.A. Pandemia de coronavírus/COVID-19 em Moçambique: Desafios de reflexão sobre os contextos territoriais e socioeconômicos da política de saúde. Geosaberes 2020, 11, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, H.F.B.; Hansine, R. Análise epidemiológica e demográfica da COVID-19 em África. An. Inst. Hig. E Med. Trop. 2020, 19, 7–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maúngue, H.B. Para uma sociologia do carisma na atualidade: Ensaio para leitura do carisma de Samora Machel. Em Tese 2014, 11, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langa, P. O homem na sociedade ou a sociedade no homem: Desafios epistémico e metodológico para uma análise sociológica do carisma de Samora Machel. Rev. Ang. Sociol. 2014, 13, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajisa, K.; Payongayong, E. Potential of and constraints to the rice Green Revolution in Mozambique: A case study of the Chokwe irrigation scheme. Food Policy 2011, 36, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilomboleni, H. African Green Revolution, food sovereignty and constrained livelihood choice in Mozambique. Can. J. Afr. Stud./Rev. Can. Des Études Afr. 2018, 52, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloi, J.A. Políticas e Estratégias de Combate à Pobreza e de Promoção do Desenvolvimento em Moçambique: Elementos de Continuidade e Descontinuidade. Rev. Estud. Políticas Públicas 2018, 4, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langa, E.N.B. Diplomacia e política externa em Moçambique: O primeiro governo pós-independência-Samora Machel. Rev. Bras. De Estud. Afr. 2021, 6, 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sambo, A.S.; Guambe, E. Abordagem ‘One Size Fits All’ Pode não ser a Mais Acertada: Declaração de Estado de Sítio em Cabo Delgado e Estado de Calamidade Pública Noutras Províncias do País? 2020. Available online: https://www.cartamz.com/index.php/politica/item/5785-declaracao-de-estado-de-sitio-em-cabo-delgado-e-estado-de-calamidade-publica-noutras-provincias-do-pais (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Muchacona, J.J.; Romão, J.C. Da Reconstrução Económica à Emergência do Regime Democrático em Moçambique. Rev. Eletrônica Discente História. Com. 2018, 5, 86–99. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, F.B.G. “A intestina batalha” socialista moçambicana através de ‘Crônica da Rua 513.2′, de João Paulo Borges Coelho. Abril: Rev. Estud. Lit. Port. E Afr.-NEPA UFF 2018, 10, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.; Forquilha, S. Navigating Civic Space in a Time of COVID-19: Mozambique Country Report; Institute for Social and Economic Studies: Maputo, Mozambique, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Aliança Moçambicana da Sociedade Civil C-19. WordPress.com, 2020. Available online: https://aliancac19.wordpress.com/ (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Assembleia da República de Moçambique. Lei da Revisão Pontual da Constituição da República de Moçambique. In Boletim da República: Publicação Oficial da República de Moçambique; de Moçambique, A.d.R., Ed.; Imprensa Nacional de Moçambique: Maputo, Mozambique, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 3–41. [Google Scholar]

- Niquice, A.R.; Filippi, E.E. Desafios socio-económicos de Moçambique no contexto da COVID-19. Rev. Cient. UEM Sér. Ciênc. Bioméd. Saúde Pública 2021. Available online: http://revistacientifica.uem.mz/revista/index.php/cbsp/article/view/103 (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- The World Bank Group. Mozambique. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/country/mozambique?view=chart (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- World Population Prospects. Total Population, Both Sexes Combined (Thousands). Available online: http://data.un.org/Data.aspx?d=PopDiv&f=variableID%3a12 (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- INE. Censo 2017: IV Recenseamento Geral da População e Habitação; Instituto Nacional de Estatística: Maputo, Mozambique, 2017; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística. INE Destaques—Instituto Nacional de Estatistica. Available online: http://www.ine.gov.mz/ (accessed on 9 August 2021).

- Galle, A.; Vermandere, H.; Griffin, S.; de Melo, M.; Machaieie, L.; Van Braeckel, D.; Degomme, O. Quality of care in family planning services in rural Mozambique with a focus on long acting reversible contraceptives: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Women’s Health 2018, 18, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marotta, C.; Nacareia, U.; Estevez, A.; Tognon, F.; Genna, G.; De Meneghi, G.; Occa, E.; Ramirez, L.; Lazzari, M.; Di Gennaro, F.; et al. Mozambican Adolescents and Youths during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Knowledge and Awareness Gaps in the Provinces of Sofala and Tete. Healthcare 2021, 9, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worldometers.info. Mozambique Population (LIVE). Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/mozambique-population/ (accessed on 9 August 2021).

- Sumbana, J.; Sacarlal, J.; Rubino, S. Air pollution and other risk factors might buffer COVID-19 severity in Mozambique. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries 2020, 14, 994–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moretti-Marques, R.; Salcedo, M.P.; Filho, D.C.; Lopes, A.; Vieira, M.; Cintra, G.F.; Ribeiro, M.; Changule, D.; Daud, S.; Rangeiro, R.; et al. Telementoring in gynecologic oncology training: Changing lives in Mozambique. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2019, 30, 150–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capurchande, R.D.; Coene, G.; Roelens, K.; Meulemans, H. Between compliance and resistance: Exploring discourses on family planning in Community Health Committees in Mozambique. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e006529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, S.C.; Constant, D.; Fraga, S.; Osman, N.B.; Harries, J. “There Are Things We Can Do and There Are Things We Cannot Do.” A Qualitative Study About Women’s Perceptions on Empowerment in Relation to Fertility Intentions and Family Planning Practices in Mozambique. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 2022, 3, 824650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Câmara, C.L. COVID-19 e o multilinguismo em Moçambique. Rev. Cient. UEM Sér. Ciênc. Bioméd. Saúde Pública 2021, 1–13. Available online: http://www.revistacientifica.uem.mz/revista/index.php/cbsp/article/view/130 (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Patel, S.; Majuisse, A.; Tem, F. Manual de Línguas Moçambicanas: Formação de Professores do Ensino Primário e Educação de Adultos; Ministério da Educação e Desenvolvimento Humano (DNFP & INDE) and Associação Progresso: Maputo, Mozambique, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- INAGE. População. Available online: https://www.portaldogoverno.gov.mz/por/Mocambique/Populacao (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- PopulationPyramid.net. Mozambique 2018. Available online: https://www.populationpyramid.net/mozambique/2018/ (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Maunze, X.H.; Dade, A.; Zacarias, M.d.F.; Cubula, B.; Alfeu, M.; Mangue, J.; Mouzinho, R.; Cassimo, M.N.; Zunguze, C.; Zavale, O.; et al. IV Recenseamento Geral da População e Habitação, 2017: Resultados definitivos—Moçambique; Instituto Nacional de Estatística: Maputo Mozambique, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Collinge, J. Criteria for commonwealth membership. Round Table 1996, 85, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento Santos, Á.R.; de Macedo Mendes, A. A mulher na narrativa de Paulina Chiziane: Ressignificando papéis de gênero na sociedade moçambicana. Estrema-Rev. Interdiscip. De Humanid. 2015, 7, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Szmidt, R. O legado tradicional africano e as influências ocidentais: A formação da identidade e da moçambicanidade na literatura pós-colonial de Moçambique. In Proceedings of the VII Congresso Ibérico de Estudos Africanos, Lisbon, Portugal, 9–11 September 2010; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mutiua, C. Religião no contexto da COVID-19 em Moçambique: Desafios e oportunidades adaptativas; Centro de Estudos Africanos, Universidade Eduardo Mondlane: Maputo, Mozambique, 2020; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Premawardhana, D. Faith in flux: Pentecostalism and mobility in rural Mozambique; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2018; p. 228. [Google Scholar]

- van de Kamp, L. Violent Conversion: Brazilian Pentecostalism and Urban Women in Mozambique; Boydell & Brewer: Woodbridge, UK, 2016; Volume 1, p. 236. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Kamp, L. Burying life: Pentecostal religion and development in urban Mozambique. In Development and Politics from Below; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 152–171. [Google Scholar]

- Salite, D.L.J. The Role of Cultural Beliefs in Shaping Farmers’ Behavioural Decisions to Adapt to Drought Risks in Gaza Province-Southern Mozambique. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Reading, Reading, UK, May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Simbine, M.G.Z. Fatores Antrópicos e Conservação da Floresta Sagrada de Chirindzene, Gaza-Moçambique. Master’s Thesis, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal, July 2013. Available online: https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt/bitstream/10216/67495/2/24443.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Jozane, T. Desafios para Regulamentação das Práticas da Medicina Tradicional e Alternativa no Sistema Nacional de Saúde em Moçambique: Documento Provisório; Universidade Eduardo Mondlane: Maputo, Mozambique, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guambe, A.J. Desafios da psicologia e da pesquisa no pós-COVID-19: Um olhar a partir do contexto de Moçambique. Rev. Psicol. Divers. E Saúde 2020, 9, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhampinga, D.A.A.; Chitata, P.A. Estratégias e desafios do ensino da matemática durante a pandemia da COVID-19 em Moçambique. Rev. Interdiscip. Em Ensino De Ciências E Matemática 2021, 1, 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mussagy, I.H. Os Efeitos do COVID-19 em Moçambique: A Economia em Ponto Morto; Universidade Católica de Moçambique: Beira, Mozambique, 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matchaya, G.; Nhlengethwa, S.; Greffiths, J.; Fakudze, B. Maize Grain Price Trends in Food Surplus and Deficit Areas of Mozambique under COVID-19. 2020. AKADEMIYA: COVID-19 Bulletin. Available online: https://akademiya2063.org/uploads/Covid-19-Bulletin-007.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Ismael, F.; Mbanze, A.; Ndayiragije, A.; Fangueiro, D. Understanding the Dynamic of Rice Farming Systems in Southern Mozambique to Improve Production and Benefits to Smallholders. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]