1. Introduction

Louis XI’s long-held reputation as a pious, paranoid ruler who preferred hunting and praying to parties and processions offers only a partial view of this misunderstood monarch’s reign. As a result of the economically debilitating Hundred Years War, Louis inherited from his father, Charles VII, a jumble of principalities and a virtually bankrupt treasury. His leadership, diplomacy, and military expansion unified and stabilised the kingdom, securing the Duchy of Brittany (in 1475 with the Treaty of Senlis), the Burgundian territories (in 1477, confirmed by the Treaty of Arras with the Habsburg emperor Maximilian I in 1482), Maine, Anjou, Provence and Fourcalquier in 1481, as well as some of the lands held by the House of Armagnac in Gascony. The financial security he achieved for the monarchy by the end of his reign paved the way for his descendants to exercise dynastic ambition through patronage.

However, Louis’ historiography was working against him from the start: Thomas Basin (1412–1491), the Burgundian chronicler and bishop of Lisieux [

1] (p. 53), called him the

universelle aragne, the universal spider, a man who lived for intrigue and plots [

2] (p. 7). Before Louis acquired the Burgundian territories in 1482, Burgundian chroniclers took great pleasure in describing the chasm between the king and the Burgundian dukes in terms of their refinement and courtliness, notably Philippe de Commynes, Jean Froissart, Georges Chastellain, and Oliver de la Marche [

1] (pp. 32–33). Georges Chastellain (1405?–1475), for example, drew attention to Philip the Good’s lavish display of magnificence that wowed the crowds at Louis XI’s coronation [

3] (pp. 53–55, 85–86, 93–94). Centuries later, commentators fanned the flames of the fire lit by the Burgundian chroniclers. In 1824, Walter Scott described the king as fearful, locked up in a prison of his own making at the royal palace at Plessis [

4]. The initial chronicles presented a biased account that tainted Louis’ biography and legacy, and to which historians still frequently refer. Even at the beginning of the 21st century, his biographer depicted him as a

grand homme, a politician and statesman with expansionist, nation-building ambitions [

5]. Rarely, if ever, was he remembered as a patron. Yet closer examination of the surviving sources reveals that Louis XI’s patronage was an essential aspect of his leadership, which he exploited through a variety of media and diverse royal iconography.

The king is regarded by historians as a monarch with simple tastes who disliked spending money on luxuries. The evidence shows that on the contrary, he spent significant sums on ecclesiastical and secular architecture, religious donations, liturgical objects, and votive offerings made from precious metals by goldsmiths, and on diplomatic gifts. The vast majority of his commissions were for religious institutions. However, instead of reading this as personal pious behaviour, we need to acknowledge the extent to which he used devotional objects and religious patronage to exercise royal diplomacy, to construct a legacy, and to promote his reign during his lifetime. Although virtually nothing survives of his many goldsmith-work religious commissions, several descriptions of these objects remain in the historical record.

The king used a variety of symbols and images to promote his royal authority and the divine legitimacy of his rule. The royal coat of arms combined the regal preciousness of gold with divine, celestial blue. The fleur-de-lys (lily) in the royal arms was considered by the Valois branch of the Capetian dynasty to be a symbol of the Holy Trinity and therefore a visual confirmation of the monarch’s divine right to rule. Louis himself decreed this sacred link, saying that his nobility and dignity “were graced by the fleur-de-lys with the countenance and the mark of Heaven” [

6] (p. 219). This can be seen on a gold coin the king had minted in around 1475, which depicts on the obverse (left), a royal coat of arms with three fleur-de-lys, topped by a crown and a sun (

Figure 1). The obverse inscription reads LVDOVICVS: DEI: GRA: FRACORVm: REX (Louis, by the grace of God, king of the Franks). The reverse side of the coin (right) depicts a cross fleurdelisée with a quadrilobe at the centre. The inscription reads: XPS: VInCIT: XPS: REGnAT: ET: ImPERAT (Christ victorious, Christ the king, Christ the ruler). The winged hart, adopted from the reign of Charles VI (1368–1422) up to Francis I (1494–1547) and embraced by Louis, symbolised the immortality of the king [

6] (p. 224). However, the symbol of royal power Louis chose most often was his own image. Images and portraits of the king were used on seals, coins and medals, and especially through votive offerings (sculptures of the king made from wax or precious metals) placed in religious settings around the kingdom, to maximise the visibility of his kingship among the people.

The location of royal imagery clearly reflects the king’s political aims, and the objects and buildings Louis commissioned or patronised form a nucleus around the royal court in the Loire region, especially the city of Tours. The king also ensured that the presence of royal images—votive offerings, liturgical objects, and stained-glass windows in particular—coalesced around the territories he acquired during his reign, and in the regions that bordered them. The entry concludes with a discussion of the king’s tomb and burial place at Notre-Dame de Cléry in the Loire, the location of which ruptured from the Capetian dynasty’s traditional choice of the royal necropolis at Saint-Denis, Paris.

This entry will focus on the following themes and types of royal iconography: the royal image; sacred lineage and the coronation; piety as a political tool; saintly patrons and the Order of Saint Michael; and innovation in burial. The king was an active participant in the patronage process, expressing his direct wishes frequently through a select group of individuals in his confidence, who oversaw projects, secured quotes from artists, and ensured that orders progressed in a timely fashion. One of the most active mediators for the king, Jean Bourré (1424–1506), was a powerful figure at the court and a patron of the arts in his own right. Bourré established himself in the Touraine region with the purchase in 1465 of the château du Plessis-Bourré [

7] (p. 204). Another key mediator in the commissioning of works was Jean Bochard (?–1484), sometimes known as Boucard, or Baucart, the bishop of Avranches from 1453 to 1484 and the king’s confessor [

8] (pp. 19–20).

2. The Royal Image: Self and Family

Louis used his own image and, by extension, members of his family, to convey the authority of the monarchy to its audience. He is the monarch with the largest number of recorded portraits in medieval France thanks to the many votive gifts made in his image, in a variety of media, which he had placed in churches around the kingdom. One of the most effective methods was to have personalised life-sized figures of himself and his queen and children made in wax, and distributed around the kingdom to serve as proxies of the royal family. The first known portrait of the king is from 1467, a life-sized image in wax, given to the cathedral of Saint Esprit in Bayonne, which he followed up a few years later with a gift of a silver retable depicting the king kneeling in prayer before the Holy Spirit, made by goldsmith André Mangot [

8] (p. 91). Bayonne was in a part of the kingdom previous Capetian kings rarely visited, yet Louis placed two images of himself in Bayonne’s cathedral to remind residents and worshippers of the monarch’s role. An inventory of 1625 in Burgundy describes an effigy offered by Louis that bore nine images of French kings kneeling in prayer [

9].

In 1466, he had a wax image made of his eldest daughter, Anne of France (then aged 5), weighing 45 pounds and probably therefore life-size, to offer to the statue of Notre-Dame-de-Cléry (the church in which he chose to be buried) [

2] (p. 46). Wax ex-votos of the royal image were cheaper and faster to disseminate around the kingdom than any other medium. However, to commemorate the birth of the Dauphin in 1470, Louis tasked his close advisor Jean Bourré to have a life-sized votive image of the child made in silver to present to the church of Puy-Notre-Dame, Anjou [

8] (p. 81). Not only did this commission promote the lineage of the royal family in precious metal, it did so in a recent territorial acquisition, following the death of his uncle, King René of Anjou, in a location where he therefore needed to assert his legitimacy to rule.

Louis chose to disseminate his royal identity on engraved portrait medals, such as the example in the

Cabinet des médailles in the

Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, made by Francesco Laurana (1430–1502), an Italian artist formerly employed by Alphonso V of Aragon (1396–1458) in Naples, and from 1461 by René of Anjou (1409–1480) [

10,

11] (

Figure 2). Louis, or his advisors, commissioned the famous Italian sculptor to cast at least three portrait medals of the king. They all show the monarch in profile, turned to the right, wearing a felt hat, with an inscription in Latin,

Diu[us] Lodovicus Rex Francorum. Although we cannot be sure for whom these medals were intended, the king’s choice of a renowned Italian artist to create the first portrait medals in France reveal the monarch’s intention to use the finest, most skilled artists to commemorate the likeness of the king. It was not important that Laurana is unlikely ever to have met Louis XI [

2] (p. 56). This ‘portrait’ depicted the king as he wished to be remembered, and the addition of the inscription was all the identification needed.

Images of the king also appeared on official seals, but in a very different format to the aforementioned idealised portrait medal by Francesco Laurana. A seal used by Louis XI on a letter dated 4 October 1468, kept at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, depicts on the reverse a small circle, within which two angels hold a large coat of arms bearing the royal fleur-de-lys, topped by a crown. The obverse, however, depicts the king enthroned and front facing, holding the symbols of his divine authority to rule, the royal staff and the main de justice, in front of a textile backdrop covered with fleur-de-lys. This is a ‘seal of majesty’, in which the king is throned ‘in majesty’, a formal device that conveyed the monarch’s legitimacy through semiotics rather than physiognomic attributes. While the modern viewer might disregard such an image as a generic portrait, Louis XI and his retinue would have considered this kind of seal an accurate and recognisable depiction of the king that effectively portrayed royal status and, most importantly, authority.

3. Sacred Lineage and Coronation Imagery

The kingdom’s monarchy believed that God had approved and anointed this one line of legitimate kings, regardless of their abilities, such as Charles VI, who was mandated to rule from 1380 to 1422 despite being insane. By the time Louis XI was on the throne, this belief had strengthened, perpetuated by specific iconography repeated one generation after another, so that by Louis’ reign the king’s appointment by God was linked uniquely to the idea of French nationhood. This religious specificity was, during the end of the medieval period, the only form of national identity that people recognised or understood [

6] (p. 19).

Louis XI deliberately and successfully used imagery, especially coronation imagery, to promote the king’s sacred right to rule [

2] (p. 57). Louis seemed to have a particular attachment to the iconography of the holy ritual of his coronation, which took place on the feast of Assumption, 15 August 1461 [

3] (pp. 57–58). He sent out images representing his coronation to diverse places in his kingdom, in different media, designed to engage and impress his subjects. Cassagnes-Brouquet identified one such surviving object, a large oak chest that Louis ordered some twenty years after his coronation for the church of Saint-Aignan, Orléans, a church to which he also generously donated. (

Figure 3) The front-facing part represents in relief the iconography of the coronation of the king of France, surrounded by the twelve peers who accompany him in the sacred ritual at Reims. The king kneels at a

prie-Dieu draped in a cloth covered in fleur-de-lys, an additional symbolic reminder of the king’s special relationship with God. The chest’s original location, in a church in the territory of the duchy of Orléans, was designed to promote the sacred nature of the royal body and the divine right to rule.

The message underpinning Louis’ God-given legitimacy through coronation imagery is repeated in a different medium, in the stained-glass windows he commissioned for Evreux cathedral in Normandy. The windows decorate the cathedral’s axial chapel dedicated to

la Mére de Dieu. Throughout his reign, Louis professed a special personal devotion to the Virgin, which is often reflected in the location of his commissions, none more so than his choice of burial place at the church of Notre-Dame-de-Cléry (see

Section 6). The Evreux chapel’s central window depicts the king wearing the crown and surrounded by dignitaries, under the protection of the

Mater Omnium, in a position reserved in traditional iconography for the Holy Roman Emperor, opposite Pope Paul II, accompanied by the bishop of Evreux, Jean Balue (1421–1491) [

2] (p. 62). Another of the windows shows the king, bare-headed and kneeling at the coronation waiting to receive the crown, framed by stone tracery in the form of the fleur-de-lys (

Figure 4). The three tracery fields at the apex of the window forming the Holy Trinity of fleur-de-lys in stone was surely a deliberate reinforcement of the mystical process of the Capetian king’s coronation. One window shows the Mother of God wearing a crown topped with fleur-de-lys.

Louis used the support of stained-glass windows elsewhere to display royal propaganda [

8] (pp. 15–16). At the church of Notre-Dame in Saint-Lô, Normandy, the windows Louis commissioned depict the coronation, multiple fleur-de-lys, and the royal lineage represented by the arms of his children [

12]. The king’s strategy to disseminate the mystique of his coronation through imagery in churches was clearly effective, as we see other institutional bodies adopting the same iconography. The

capitouls of Toulouse, for example, ordered a wall painting from Antonio Contarini representing the coronation of Louis XI for their

salle du Consistoire de la Maison Communale [

2] (p. 62). Louis also adopted more ephemeral supports to portray iconography relating to his sacred right to rule for the celebrations around royal entries. When he made his first entry into one of his favoured towns, the canopy above the king was covered with fleur-de-lys, and fountains were sculpted into the shape of lilies [

6] (p. 224). Popular events such as these meant that people from all walks of life would come into contact with the royal iconography of the fleur-de-lys and associate it with the beneficence and authority of the king.

4. Piety and Politics: Goldsmith Work

Louis’s reputation for humble living was not replicated in his patronage of objects in precious metals for churches. Although the vast majority of these items were lost in the Wars of Religion or melted down during the Revolution, descriptions of them survive. As with his commissions in other media, Louis reveals geographic preferences for his generosity, with 17 goldsmith donations documented for churches in the royal territory of the Loire, and many fewer (three) in Paris [

8] (pp. 26–27). In 1466 at the royal sanctuary of Saint-Martin, Tours, the king had an image of himself in gilded silver placed opposite the saint’s holy relics (now gone, but described in the abbey’s inventory of 1493.) Then, in 1475, he added to this devotional offering with the gift of a large plate of gilded silver, inscribed in enamelled lettering

Rex Francorum Ludovicus XI hoc fecit fieri opus anno M CCCC LXXIIII, which was placed in front of the reliquary chest of Saint Martin [

2] (p. 48, footnotes 95 and 97).

Like other Christian rulers of his era, Louis would have made no distinction between piety and diplomacy when ordering precious liturgical objects and making donations to religious institutions. He was, however, an exceptionally generous patron in this area, and his political motivations were especially evident when donating to churches in territories held by his rivals. For example, after Charles the Bold died in 1477, Louis was quick to show his generosity by founding a chapel in the Burgundian duke’s territory, dedicated to Saint-Sauveur, in the church of Saint-Servais, Maastricht, and ordering for the sanctuary of Notre-Dame in Boulogne-sur-Mer, Picardy a gold heart worth 2000 ecus [

13] (p. 157). He also showed an enthusiasm for donating to pilgrimage destinations, such as the arm reliquary at Notre-Dame d’Aix-la-Chapelle in honour of Charlemagne, which miraculously still survives. This luxury devotional object includes a band of fleur-de-lys around the base, and beneath the relic’s crystal viewing window, a crystal plaque bears the arms of France surmounted by a royal crown [

8] (p. 69). The extent to which Louis believed pious donations could bring political benefits was demonstrated clearly in 1475, when he promised to the altar of Notre-Dame-de-la-Paix in the cathedral of Beauvais 3000 Tours pounds if the town managed to repel the English. The residents of Beauvais fulfilled this promise and Louis duly made the donation. Additionally after this event, Louis donated to the altar of his favourite sanctuary, Notre-Dame-de-Cléry, two models in silver of two towns where he had pulled off the most spectacular victories, at Arques and Dieppe [

2] (p. 63).

5. Saintly Patrons and the Order of Saint Michael

The king professed special devotion to a select number of saintly patrons, notably the Virgin Mary, Saint Martin of Tours and, most of all, the archangel Saint Michael. These devotional leanings are translated into the iconography and the locations of the objects he commissioned. In 1478 and 1479 in his home territory of Tours, for example, Louis had two statues of Saint Martin made, one for the chapel of Bonaventure, and the other, sculpted by Jacques François and painted by Jean Bourdichon (c.1457–c.1520), for his private chapel in Plessis—a locally important saint both for himself and for the people of Tours [

14] (p. 238).

Louis inherited a special devotion to Saint Michael from his father, Charles VII. The dragon-slaying saint was a good fit for Charles, who sought celestially endorsed military protection while fighting the Hundred Years War. Charles believed the saint had protected the sanctuary of Mont-Saint-Michel from destruction at the hands of the English, and made Saint Michael the kingdom’s guardian angel when France was finally liberated around 1450. Louis went on pilgrimage three times to Mont-Saint-Michel, the saint’s foundational town, and accorded the abbey the right to include the Capetian symbol of the three fleur-de-lys on its arms [

15] (pp. 513–542). In doing this, Louis had incorporated royal insignia on the same support as Saint Michael imagery to forge a new iconographic symbol that declared Saint Michael to be a protector of the monarchy, linking the saint inextricably to the king’s own reign. Louis used royal iconography for political aims through the considered placing of objects in locations where he needed to assert his royal authority, such as recently acquired territories and bordering regions. He offered statues of Saint Michael to several churches in such locations, including at Belpech, Aude, which neighboured the territory of the count of Foix, whose loyalty to the king was uncertain [

6] (p. 171).

The king’s special relationship with the saint, however, is seen most clearly through his foundation of a chivalric order in the saint’s name. Louis XI founded the Order of Saint Michael in 1469, its statutes decreed at Amboise on 1 August. Members had to attend annual meetings and celebrations at the seat of the order in Mont-Saint-Michel, wearing livery of white damask linen embroidered with golden-shell motifs and a chain of gold shells with a pendant depicting Saint Michael’s battle with the dragon, which they were supposed never to take off. Unlike other orders such as the Burgundian Order of the Golden Fleece, members were not allowed to join any other order. Through his leadership of the order and the imagery associated with it, Louis manipulated the saint’s reputation as guardian of the kingdom in order to reinforce the power of the monarchy and to control the aristocracy. Beaune has proposed that Louis’ order was more a cult of the king than of Saint Michael [

6] (p. 162). The king commissioned a frontispiece from his court painter, Jean Fouquet (c.1420–c.1481), for his own copy of the Statutes of the Order of Saint Michael (

Figure 5). Fouquet’s illumination places the king at the very centre of the image, wearing the order’s livery and chain of golden scallop shells. He is surrounded by the founding members, and on the wall behind him, above his head, hangs a picture of Saint Michael slaying the dragon. The archangel is dwarfed by the presence of the king. Beneath the illumination, Fouquet painted two angels wearing armour made of scallop shells, holding the chain of the order, above which sits a royal coat of arms topped with a crown. This iconography suggests that the saint, once primarily a holy protector of the kingdom, had morphed through Louis’ patronage into a symbol of loyalty to the powerful monarch. Louis used the imagery of Saint Michael to endorse and legitimise his own political achievements in his expansion of royal territory and to manipulate the aristocracy. He used images of Saint Michael in secular and religious settings to achieve this.

6. Burial and Iconographic Innovation

Generation after generation of Capetian monarchs chose the royal necropolis at Saint-Denis near Paris as their final resting place. Louis XI’s decision early on in his reign to be buried in the pilgrimage church of Notre-Dame-de-Cléry near Orléans, rather than beside previous kings and queens of France, was therefore nothing short of revolutionary. He based his decision on a special devotion to the miracle-working wooden statue of the Virgin in the church [

16] (p. 20). However, this choice was not simply motivated by piety. He believed he owed his military successes against the English, and at the Battle of Montlhéry during the League of the Public Weal (16 July 1465), to the intercessory power of Our Lady of Cléry [

2] (pp. 238–239). Louis channelled money into the beautification of the church throughout his reign, both in homage to the Virgin and to prepare a sepulchre fit for a king.

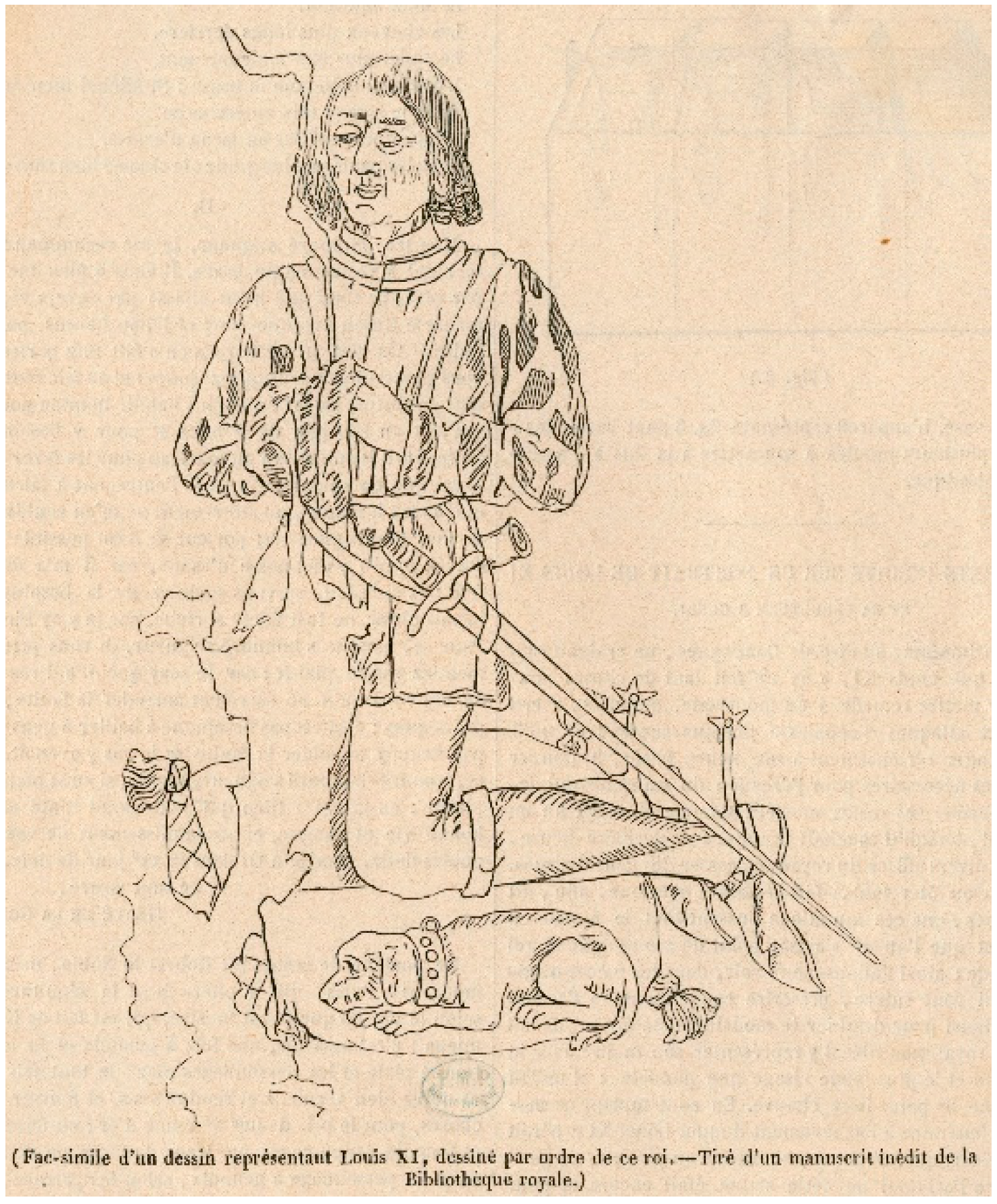

As with his choice of burial place, the tomb that Louis envisaged would hold his body marks another innovation. Recumbent stone effigies were the norm for Capetian monarchs, whereas Louis specified a kneeling effigy to be cast in bronze. The king wanted to be depicted dressed in his hunting gear, rather than in royal clothing. He initially addressed the need for a tomb in 1474, paying Jean Fouquet for a working drawing, and sculptor Michel Colombe (c.1430–1515) for a carved model of the drawing, featuring ‘the king’s portrait and likeness’ [

17] (p. 341). Louis did not approve either design and waited until 1481 before re-engaging with his tomb commission. He charged Jean Bourré with sending his wishes to Colin d’Amiens for a new design [

18] (pp. 185–194). This monument was built, and later destroyed, in the Wars of Religion in 1562, but a sketch with written instructions Bourré sent to Colin d’Amiens survives [

19] (

Figure 6).

The annotations Jean Bourré made around the sketch (not pictured) request that the sculptor modify and even improve the monarch’s appearance. He said that the king ‘[must be] dressed like a hunter, with the most handsome of faces, youthful and broad; with a slightly longish and high-set nose, as you are aware. And don’t make him bald!’ [

17] (p. 341). The instructions also specified that the effigy should be placed on the stone tomb, decorated with six coats of arms of the king, made in gilded bronze. The iconographic novelty of a kneeling effigy in bronze was adopted by future generations, including Louis’ son, the future Charles VIII and his wife Anne of Brittany, and then by the circle of elite nobles orbiting the king, including cardinal Georges d’Amboise (1460–1510) at Rouen cathedral [

20] (pp. 241–259). The king who would be remembered for his diplomacy rather than his art patronage, in reality, pioneered tomb iconography for future monarchs and their acolytes.