Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Anxiety, and Depression in Post-COVID-19 Patients Undergoing Psychotherapy: A Nonrandomized Clinical Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

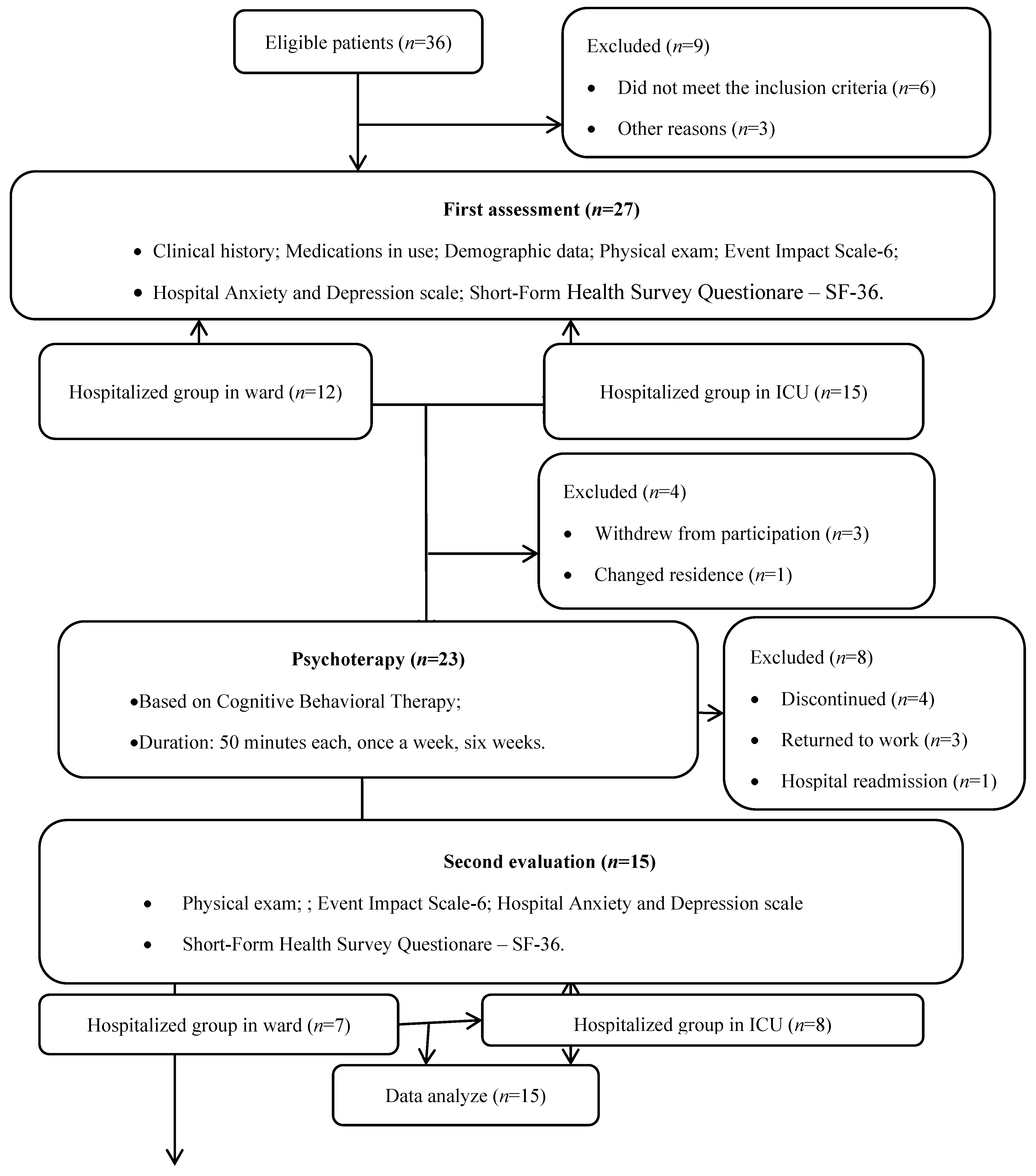

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Ethical Aspects

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

2.3.2. Impact of Events Scale-6 (IES-6)

2.3.3. Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36)

2.4. Psychological Intervention

2.5. Statistical Analysis and Sample Size

3. Results

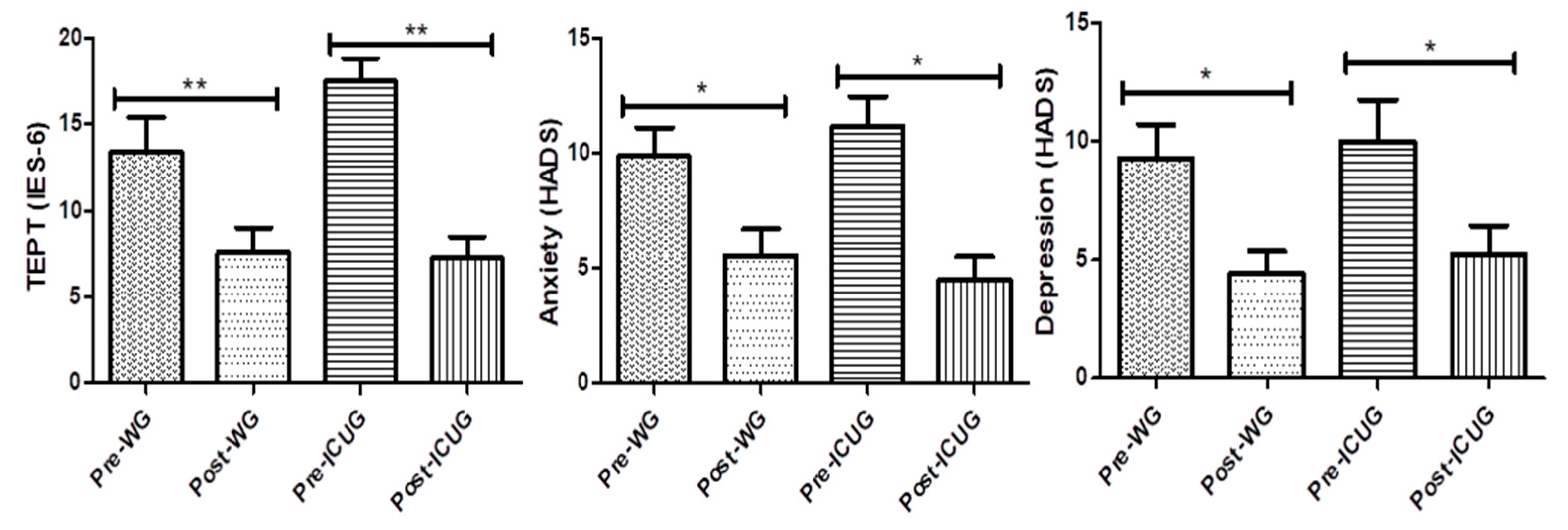

Intragroup Changes (Pre- vs. Post-Intervention)

- PTSD: both in the WG group (p = 0.001; d = 1.19) and ICUG group (p = 0.004; d = 2.71, 95% CI [1.19, 4.05]).

- Anxiety: both in the WG group (p = 0.014; d = 1.63) and ICUG group (p = 0.014; d = 1.55, 95% CI [0.49, 2.51]).

- Depression: both in the WG group (p = 0.014; d = 0.99) and ICUG group (p = 0.014; d = 1.12, 95% CI [0.16, 1.98]).

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Results

4.2. Implications

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. 2021. Available online: https://covid19.who.int (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- World Health Organization. Diagnostic Testing for SARS-CoV-2: Interim Guidance. COVID-19: Laboratory and Diagnosis. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/diagnostic-testing-for-sars-cov-2 (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Jung, G.; Ha, J.S.; Seong, M.; Song, J.H. The Effects of Depression and Fear in Dual-Income Parents on Work-Family Conflict During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sage Open 2023, 13, 21582440231157662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, A.; Achak, D.; Saad, E.; Hilali, A.; Youlyouz-Marfak, I.; Marfak, A. Post-COVID-19 mental health and its associated factors at 3-months after discharge: A case-control study. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2022, 17, 101141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Molina, A.; García-Carmona, S.; Espiña-Bou, M.; Rodríguez-Rajo, P.; Sánchez-Carrión, R.; Enseñat-Cantallops, A. Neuropsychological rehabilitation for post-COVID-19 syndrome: Results of a clinical programme and six-month follow up. Neurologia (Engl. Ed.) 2022, 39, 592–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.M.; Wong, J.G.; McAlonan, G.M.; Cheung, V.; Cheung, C.; Sham, P.C.; Chu, C.-M.; Wong, P.-C.; Tsang, K.W.; Chua, S.E. Stress and psychological distress among SARS survivors 1 year after the outbreak. Can. J. Psychiatry 2007, 52, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Shin, H.-S.; Park, H.Y.; Kim, J.L.; Lee, J.J.; Lee, H.; Won, S.-D.; Han, W. Depression as a Mediator of Chronic Fatigue and Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms in Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Survivors. Psychiatry Investig. 2019, 16, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, N.; Zhao, Y.-M.; Yan, W.; Li, C.; Lu, Q.-D.; Liu, L.; Ni, S.-Y.; Mei, H.; Yuan, K.; Shi, L.; et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of long term physical and mental sequelae of COVID-19 pandemic: Call for research priority and action. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altundal Duru, H.; Yılmaz, S.; Yaman, Z.; Boğahan, M.; Yılmaz, M. Individuals’ Coping Styles and Levels of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Turkey: A Web-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Sage Open 2023, 13, 21582440221148628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filgueiras, A.; Stults-Kolehmainen, M. Risk Factors for Potential Mental Illness Among Brazilians in Quarantine Due To COVID-19. Psychol. Rep. 2022, 125, 723–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellan, M.; Soddu, D.; Balbo, P.E.; Baricich, A.; Zeppegno, P.; Avanzi, G.C.; Baldon, G.; Bartolomei, G.; Battaglia, M.; Battistini, S.; et al. Respiratory and Psychophysical Sequelae Among Patients With COVID-19 Four Months After Hospital Discharge. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2036142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerle, M.B.; Sales, D.S.; Pinheiro, P.G.; Gouvea, E.G.; de Almeida, P.I.F.; de Araujo Davico, C.; Souza, R.S.; Spedo, C.T.; Nicaretta, D.H.; Alvarenga, R.M.P.; et al. Cognitive Complaints Assessment and Neuropsychiatric Disorders After Mild COVID-19 Infection. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2023, 38, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Li, X.; Gu, X.; Zhang, H.; Ren, L.; Guo, L.; Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Cui, D.; Wang, Y.; et al. Health outcomes in people 2 years after surviving hospitalisation with COVID-19: A longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 863–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taquet, M.; Geddes, J.R.; Husain, M.; Luciano, S.; Harrison, P.J. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: A retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jassas, H.K.; Al-Hakeim, H.K.; Maes, M. Intersections between pneumonia, lowered oxygen saturation percentage and immune activation mediate depression, anxiety, and chronic fatigue syndrome-like symptoms due to COVID-19: A nomothetic network approach. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 297, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akova, İ.; Kiliç, E.; Özdemir, M.E. Prevalence of Burnout, Depression, Anxiety, Stress, and Hopelessness Among Healthcare Workers in COVID-19 Pandemic in Turkey. Inquiry 2022, 59, 469580221079684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolato, B.; Carvalho, A.F.; Soczynska, J.K.; Perini, G.I.; McIntyre, R.S. The Involvement of TNF-α in Cognitive Dysfunction Associated with Major Depressive Disorder: An Opportunity for Domain Specific Treatments. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2015, 13, 558–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, X.; Liu, Y.; Lei, X.; Li, P.; Mi, D.; Ren, L.; Guo, L.; Guo, R.; Chen, T.; Hu, J.; et al. Characterization of spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 on virus entry and its immune cross-reactivity with SARS-CoV. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badenoch, J.; Cross, B.; Hafeez, D.; Song, J.; Watson, C.; Butler, M.; Nicholson, T.R.; Rooney, A.G. Post-traumatic symptoms after COVID-19 may (or may not) reflect disease severity. Psychol. Med. 2023, 53, 295–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.P.; Chesney, E.; Oliver, D.; Pollak, T.A.; McGuire, P.; Fusar-Poli, P.; Zandi, M.S.; Lewis, G.; David, A.S. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Yao, Q.; Gu, X.; Wang, Q.; Ren, L.; Wang, Y.; Hu, P.; Guo, L.; Liu, M.; Xu, J.; et al. 1-year outcomes in hospital survivors with COVID-19: A longitudinal cohort study. Lancet 2021, 398, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huth, D.; Bräscher, A.K.; Tholl, S.; Fiess, J.; Birke, G.; Herrmann, C.; Jöbges, M.; Mier, D.; Witthöft, M. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with post-COVID-19 condition (CBT-PCC): A feasibility trial. Psychol. Med. 2024, 54, 1122–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuut, T.A.; Müller, F.; Csorba, I.; Braamse, A.; Aldenkamp, A.; Appelman, B.; Assmann-Schuilwerve, E.; Geerlings, S.E.; Gibney, K.B.; Kanaan, R.A.A.; et al. Efficacy of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Targeting Severe Fatigue Following Coronavirus Disease 2019: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 77, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Jiang, R.; Chen, N.; Qu, W.; Liu, D.; Zhang, M.; Fan, H.; Zhao, Y.; Tan, S. Self-help cognitive behavioral therapy application for COVID-19-related mental health problems: A longitudinal trial. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2021, 60, 102656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Des Jarlais, D.C.; Lyles, C.; Crepaz, N.; TREND Group. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: The TREND statement. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolovski, A.; Gamgoum, L.; Deol, A.; Quilichini, S.; Kazemir, E.; Rhodenizer, J.; Oliveira, A.; Brooks, D.; Alsubheen, S. Psychometric properties of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in individuals with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): A systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2024, 46, 1230–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosey, M.M.; Leoutsakos, J.-M.S.; Li, X.; Dinglas, V.D.; Bienvenu, O.J.; Parker, A.M.; Hopkins, R.O.; Needham, D.M.; Neufeld, K.J. Screening for posttraumatic stress disorder in ARDS survivors: Validation of the Impact of Event Scale-6 (IES-6). Crit. Care 2019, 23, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.E., Jr.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med. Care 1992, 30, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.S.; Beck, A.T.; Knapp, P.; Meyer, E.; da Rosa, S.M. Terapia Cognitivo-Comportamental: Teoria e Prática, 2nd ed.; Artmed: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, J.S.; Knapp, P.; da Rosa, S.M.M. Terapia Cognitivo-Comportamental: Teoria e Prática, 3rd ed.; Artmed: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Zhou, F.; Hou, W.; Silver, Z.; Wong, C.Y.; Chang, O.; Huang, E.; Zuo, Q.K. The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances in COVID-19 patients: A meta-analysis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2021, 1486, 90–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, M.G.; De Lorenzo, R.; Conte, C.; Poletti, S.; Vai, B.; Bollettini, I.; Melloni, E.M.T.; Furlan, R.; Ciceri, F.; Rovere-Querini, P.; et al. Anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors: Role of inflammatory and clinical predictors. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 89, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrijo, M.; Oliveira, M.C.; Oliveira, A.C.; Lino, M.E.M.; Souza, S.K.; Afonso, J.P.R.; Moura, R.S.; Fonseca, D.R.; Fonseca, A.L.; Tomaz, R.S.; et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression in post-COVID19 patients: Integrative review. Man. Ther. Posturology Rehabil. J. 2022, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro-Delmo, J.; Portillo De-Antonio, P.; Porras-Segovia, A.; de León-Martínez, S.; Figuero Oltra, M.; del Pozo-Herce, P.; Sánchez-Escribano Martínez, A.; Abejón Pérez, I.; Vera-Varela, C.; Postolache, T.T.; et al. Onset of mental disorders following hospitalization for COVID-19: A 6-month follow-up study. COVID 2023, 3, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlake, J.H.; Wesselius, S.; van Genderen, M.E.; van Bommel, J.; Boxma-de Klerk, B.; Wils, E.J. Psychological distress and health-related quality of life in patients after hospitalization during the COVID-19 pandemic: A single-center, observational study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldızeli, S.O.; Kocakaya, D.; Saylan, Y.H.; Tastekin, G.; Yıldız, S.; Akbal, Ş.; Özkan, S.; Arıkan, H.; Karakurt, S. Anxiety, Depression, and Sleep Disorders After COVID-19 Infection. Cureus 2023, 15, e42637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasselli, G.; Zangrillo, A.; Zanella, A.; Antonelli, M.; Cabrini, L.; Castelli, A.; Cereda, D.; Coluccello, A.; Foti, G.; Fumagalli, R.; et al. Baseline Characteristics and Outcomes of 1591 Patients Infected With SARS-CoV-2 Admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA 2020, 323, 1574–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, A.N.; Zhu, S.; Cooper, N.; Roderick, P.; Alwan, N.; Tarrant, C.; Ziauddeen, N.; Yao, G.L. Impact of Covid-19 on health-related quality of life of patients: A structured review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.-T.; Yang, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Cheung, T.; Ng, C.H. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 228–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First, M.B. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Volume 201, pp. 727–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonazza, F.; Borghi, L.; di San Marco, E.C.; Piscopo, K.; Bai, F.; Monforte, A.D.A.; Vegni, E. Psychological outcomes after hospitalization for COVID-19: Data from a multidisciplinary follow-up screening program for recovered patients. Res. Psychother. 2021, 23, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanbehzadeh, S.; Tavahomi, M.; Zanjari, N.; Ebrahimi-Takamjani, I.; Amiri-Arimi, S. Physical and mental health complications post-COVID-19: Scoping review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2021, 147, 110525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coventry, P.A.; Meader, N.; Melton, H.; Temple, M.; Dale, H.; Wright, K.; Cloitre, M.; Karatzias, T.; Bisson, J.; Roberts, N.P.; et al. Psychological and pharmacological interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid mental health problems following complex traumatic events: Systematic review and component network meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, J.; Schwarzer, G.; Gerger, H. Comparative Efficacy and Acceptability of Pharmacological, Psychotherapeutic, and Combination Treatments in Adults With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Network Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 904–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.C.; Carrijo, M.M.; Afonso, J.P.R.; Moura, R.S.; Oliveira, L.F.R.; Fonseca, A.L.; Melo, V.V.; Lino, M.E.M.; Sousa, B.N.; Póvoa, E.R.; et al. Effects of hospitalization on functional status and health-related quality of life of patients with COVID-19 complications: A literature review. Man. Ther. Posturology Rehabil. J. 2022, 20, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germann, N.; Amozova, D.; Göhl-Freyn, K.; Fischer, T.; Frischknecht, M.; Kleger, G.-R.; Pietsch, U.; Filipovic, M.; Brutsche, M.H.; Frauenfelder, T.; et al. Evaluation of psychosomatic, respiratory, and neurocognitive health in COVID-19 survivors 12 months after ICU discharge. COVID 2024, 4, 1172–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koullias, E.; Fragkiadakis, G.; Papavdi, M.; Manousopoulou, G.; Karamani, T.; Avgoustou, H.; Kotsi, E.; Niakas, D.; Vassilopoulos, D.; Koullias, E. Long-Term Effect on Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients With COVID-19 Requiring Hospitalization Compared to Non-hospitalized COVID-19 Patients and Healthy Controls. Cureus 2022, 14, e31342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silveira, A.D.; Scolari, F.L.; Saadi, M.P.; Brahmbhatt, D.H.; Milani, M.; Milani, J.G.P.O.; Junior, G.C.; Sartor, I.T.S.; Zavaglia, G.O.; Tonini, M.L.; et al. Long-term reduced functional capacity and quality of life in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Front. Med. 2024, 10, 1289454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizanaj, N.; Gavazaj, F. Effects of depressive and anxiety-related behaviors in patients aged 30–75+ who have experienced COVID-19. COVID 2024, 4, 1041–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, J.; Cieślik, B.; Szary, P.; Rutkowski, S.; Szczegielniak, J.; Szczepańska-Gieracha, J.; Gajda, R. Association of Acute Headache of COVID-19 and Anxiety/Depression Symptoms in Adults Undergoing Post-COVID-19 Rehabilitation. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Qiao, D.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Yang, Y.; Wen, D.; Li, X.; Nie, X.; Dong, Y.; Tang, S.; et al. The Efficacy of Computerized Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Patients With COVID-19: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e26883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asimakos, A.; Spetsioti, S.; Mavronasou, A.; Gounopoulos, P.; Siousioura, D.; Dima, E.; Gianniou, N.; Sigala, I.; Zakynthinos, G.; Kotanidou, A.; et al. Additive benefit of rehabilitation on physical status, symptoms and mental health after hospitalisation for severe COVID-19 pneumonia. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2023, 10, e001377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, H.; Saffari, M.; Movahedi, M.; Sanaeinasab, H.; Rashidi-Jahan, H.; Pourgholami, M.; Poorebrahim, A.; Barshan, J.; Ghiami, M.; Khoshmanesh, S.; et al. A mediating role for mental health in associations between COVID-19-related self-stigma, PTSD, quality of life, and insomnia among patients recovered from COVID-19. Brain Behav. 2021, 11, e02138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zysberg, L.; Zisberg, A. Days of worry: Emotional intelligence and social support mediate worry in the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, X.; Jiang, J.; Xu, X.; Wu, J.; Xu, Y.; Lin, X.; Hall, J.; Xu, H.; Xu, J.; et al. The Effect of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in Patients With COVID-19: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 580827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Kong, F.; Zheng, K.; Tang, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Diao, L.; Wu, S.; Jiao, P.; et al. Effect of Psychological-Behavioral Intervention on the Depression and Anxiety of COVID-19 Patients. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 586355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vink, M.; Vink-Niese, A. Could Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Be an Effective Treatment for Long COVID and Post COVID-19 Fatigue Syndrome? Lessons from the Qure Study for Q-Fever Fatigue Syndrome. Healthcare 2020, 8, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangemi, A.; Gragnani, A.; Dahò, M.; Buonanno, C. Reducing Probability Overestimation of Threatening Events: An Italian Study on the Efficacy of Cognitive Techniques in Non-Clinical Subjects. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2019, 16, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aravind, A.; Agarwal, M.; Malhotra, S.; Ayyub, S. Effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on Mental Health Issues: A Systematic Review. Ann. Neurosci. 2024, 32, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Total (n = 15) | WG (n = 7) | ICUG (n = 8) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (sd) | 53.4 (14.1) | 51.7 (17.4) | 54.9 (11.4) | 0.68 1 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.28 2 | |||

| Female | 10 (66.7) | 6 (85.7) | 4 (50) | |

| Male | 5 (33.3) | 1 (14.3) | 4 (50) | |

| Self-reported race, n (%) | 0.5 2 | |||

| White | 2 (13.4) | 0 | 2 (25.0) | |

| Brown | 8 (53.3) | 5 (71.4) | 3 (37.5) | |

| Black | 5 (33.3) | 2 (28.6) | 3 (37.5) | |

| Educational status, n (%) | 1 2 | |||

| Incomplete elementar school | 2 (13.3) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (12.5) | |

| Complete primary school | 3 (20.0) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (25.0) | |

| High school | 7 (46.7) | 3 (42.9) | 4 (50.0) | |

| University education | 3 (20.0) | 2 (28.6) | 1 (12.5) | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| DM | 4 (26.7) | 1 (14.3) | 3 (37.5) | 0.56 2 |

| SAH | 6 (40.0) | 2 (28.6) | 4 (50.0) | 0.6 2 |

| Obesity | 3 (20.0) | 0 | 3 (37.5) | 0.2 2 |

| Anxiety, n (%) | 8 (53.3) | 2 (28.6) | 6 (75.0) | 0.13 1 |

| Depression, n (%) | 3 (20.0) | 2 (28.6) | 1 (12.5) | 0.56 1 |

| Hospitalization time, n (%) | 11.3 (10.1) | 6.4 (6.5) | 15.5 (11.2) | 0.08 1 |

| Post-Intervention | p ICUG Pre x Post 2 | p WG Pre x Post 2 | p ICUG Pre x Post 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WG (n = 7) | ICUG (n = 8) | p | WG (n = 7) | ICUG (n = 8) | p | |||

| IES | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| <10 | 2 (28.6) | 0 | 6 (85.7) | 7 (87.5) | ||||

| ≥10 | 5 (71.4) | 8 (100.0) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (12.5) | ||||

| TEPT | 1 | --- | 0.38 | 0.34 | ||||

| <1.09 | 4 (57.1) | 4 (50.0) | 7 (100.0) | 8 (100.0) | ||||

| ≥1.09 | 3 (42.9) | 4 (50.0) | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Depression (HADS-D) | 0.53 | 0.56 | --- | --- | ||||

| Unlikely diagnosis | 1 (14.3) | 2 (25.0) | 6 (85.7) | 5 (62.5) | ||||

| Possible diagnosis | 4 (57.1) | 2 (25.0) | 1 (14.3) | 3 (37.5) | ||||

| Probable diagnosis | 2 (28.6) | 4 (50.0) | ||||||

| Anxiety (HADS-A) | 1 | 0.56 | --- | --- | ||||

| Unlikely diagnosis | 1 (14.3) | 1 (12.5) | 5 (71.4) | 7 (87.5) | ||||

| Possible diagnosis | 4 (57.1) | 4 (50.0) | 2 (28.6) | 1 (12.5) | ||||

| Probable diagnosis | 2 (28.6) | 3 (37.5) | ||||||

| Variable | Pre-Intervention | Pos-Intervention | Analysis Pre vs. Post | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WG Mean (DP) | ICUG Mean (DP) | WG Mean (DP) | ICUG Mean (DP) | WG (p; Cohen’s d) | ICUG (p; Cohen’s d) | |

| TEPT | 13.43 (4.92) | 17.50 (3.78) | 7.57 (3.50) | 7.25 (3.49) | 0.001; 1.19 | 0.004; 2.71 |

| Depression (HADS) | 9.29 (3.77) | 10.00 (4.93) | 5.57 (3.05) | 4.50 (2.93) | 0.014; 0.99 | 0.014; 1.12 |

| Anxiety (HADS) | 9.86 (3.34) | 11.13 (3.80) | 4.43 (2.44) | 5.25 (3.37) | 0.014; 1.63 | 0.014; 1.55 |

| Pre-Intervention | Post-Intervention | p ICUG Pre x Post 2 | p WG Pre x Post 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-36 | ICUG | WG | p 1 | ICUG | WG | p 1 | ||

| Functional capacity | 28.7 (19.3) | 50.7 (30.6) | 0.11 | 56.2 (25.6) | 62.1 (24.5) | 0.65 | 0.01 | 0.17 |

| Physical aspects | 0 | 42.8 (42.6) | 0.006 2 | 28.1 (33.9) | 46.4 (36.6) | 0.33 | 0.04 | 0.79 |

| Pain | 55.5 (30.0) | 58.6 (27.2) | 0.84 | 71.2 (27.7) | 64.6 (24.9) | 0.63 | 0.13 | 0.41 |

| General health status | 48.6 (15.1) | 50.3 (19.2) | 0.85 | 55.5 (11.6) | 64.6 (16.9) | 0.24 | 0.18 | 0.01 |

| Vitality | 49.4 (18.0) | 50.7 (7.3) | 0.55 | 63.1 (18.7) | 62.1 (20.8) | 0.92 | 0.01 | 0.12 |

| Social aspects | 48.4( 25.4) | 55.3 (25.9) | 0.61 | 65.6 (23.8) | 67.8 (27.8) | 0.87 | 0.12 | 0.15 |

| Emotional aspects | 25 (23.8) | 61.9 (35.6) | 0.01 | 58.3 (38.8) | 57.1 (16.2) | 0.94 | 0.01 | 0.8 |

| Mental Health | 52.7 (22.3) | 52.6 (14.7) | 0.98 | 66.5 (21.8) | 66.8 (17.5) | 0.97 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carrijo, M.M.; Oliveira, M.C.; Canedo, W.A.O.; Afonso, J.P.R.; Paixão, H.N.C.; Alves, L.R.; Palma, R.K.; Oliveira-Silva, I.; Silva, C.H.M.; Oliveira, R.F.; et al. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Anxiety, and Depression in Post-COVID-19 Patients Undergoing Psychotherapy: A Nonrandomized Clinical Trial. COVID 2025, 5, 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5110184

Carrijo MM, Oliveira MC, Canedo WAO, Afonso JPR, Paixão HNC, Alves LR, Palma RK, Oliveira-Silva I, Silva CHM, Oliveira RF, et al. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Anxiety, and Depression in Post-COVID-19 Patients Undergoing Psychotherapy: A Nonrandomized Clinical Trial. COVID. 2025; 5(11):184. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5110184

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarrijo, Marilúcia M., Miriã C. Oliveira, Washington A. O. Canedo, João Pedro R. Afonso, Heren N. C. Paixão, Larissa R. Alves, Renata K. Palma, Iranse Oliveira-Silva, Carlos H. M. Silva, Rodrigo F. Oliveira, and et al. 2025. "Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Anxiety, and Depression in Post-COVID-19 Patients Undergoing Psychotherapy: A Nonrandomized Clinical Trial" COVID 5, no. 11: 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5110184

APA StyleCarrijo, M. M., Oliveira, M. C., Canedo, W. A. O., Afonso, J. P. R., Paixão, H. N. C., Alves, L. R., Palma, R. K., Oliveira-Silva, I., Silva, C. H. M., Oliveira, R. F., Oliveira, D. A. A. P., Andraus, R. A. C., Vieira, R. P., Castelnuovo, G., Capodaglio, P., & Oliveira, L. V. F. (2025). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Anxiety, and Depression in Post-COVID-19 Patients Undergoing Psychotherapy: A Nonrandomized Clinical Trial. COVID, 5(11), 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid5110184