Medical Student Voices on the Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Motivation to Study: A Mixed-Method Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analyses

2.5. Ethical Statement

3. Results

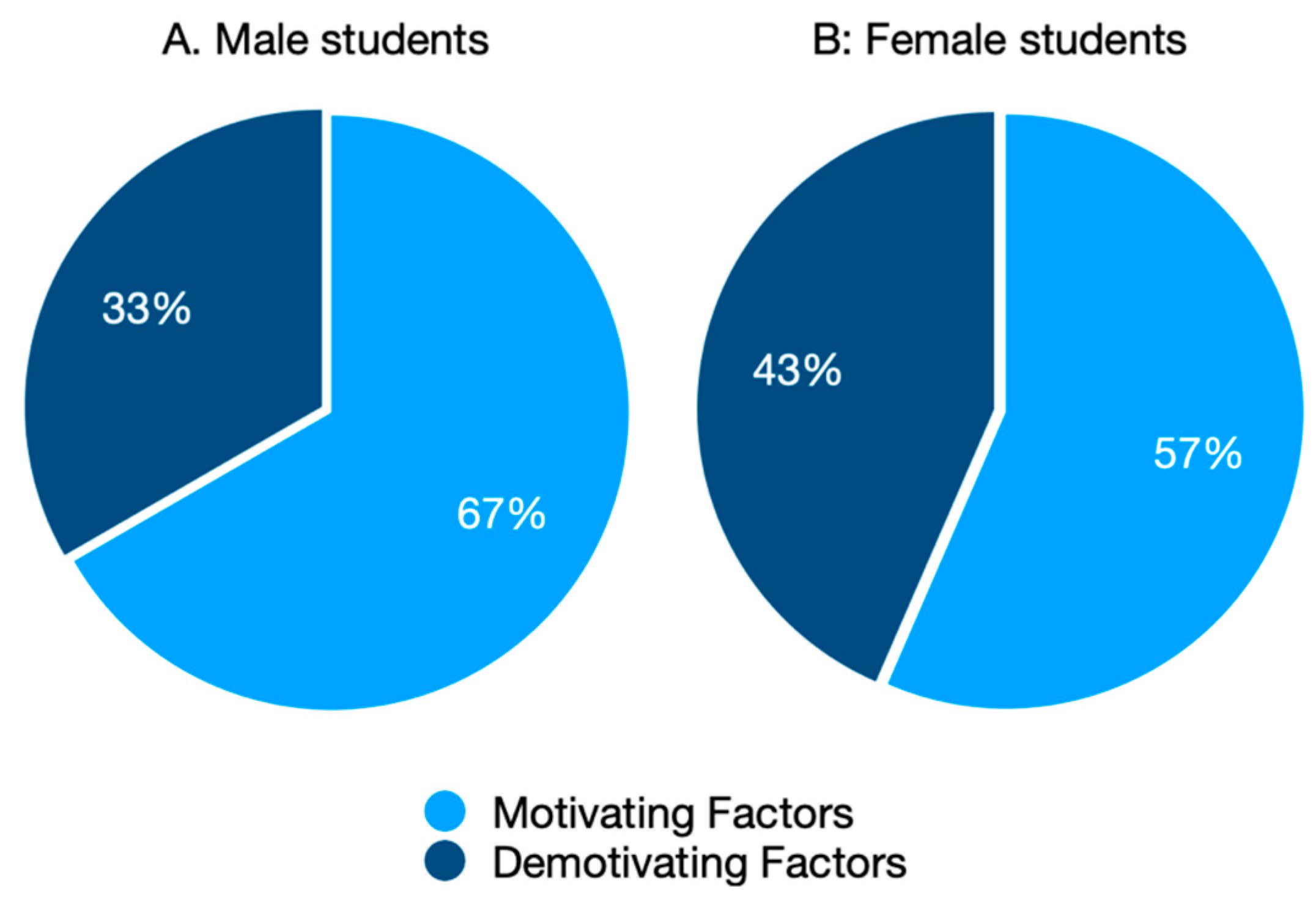

3.1. Motivation Status

3.2. Coding Analysis

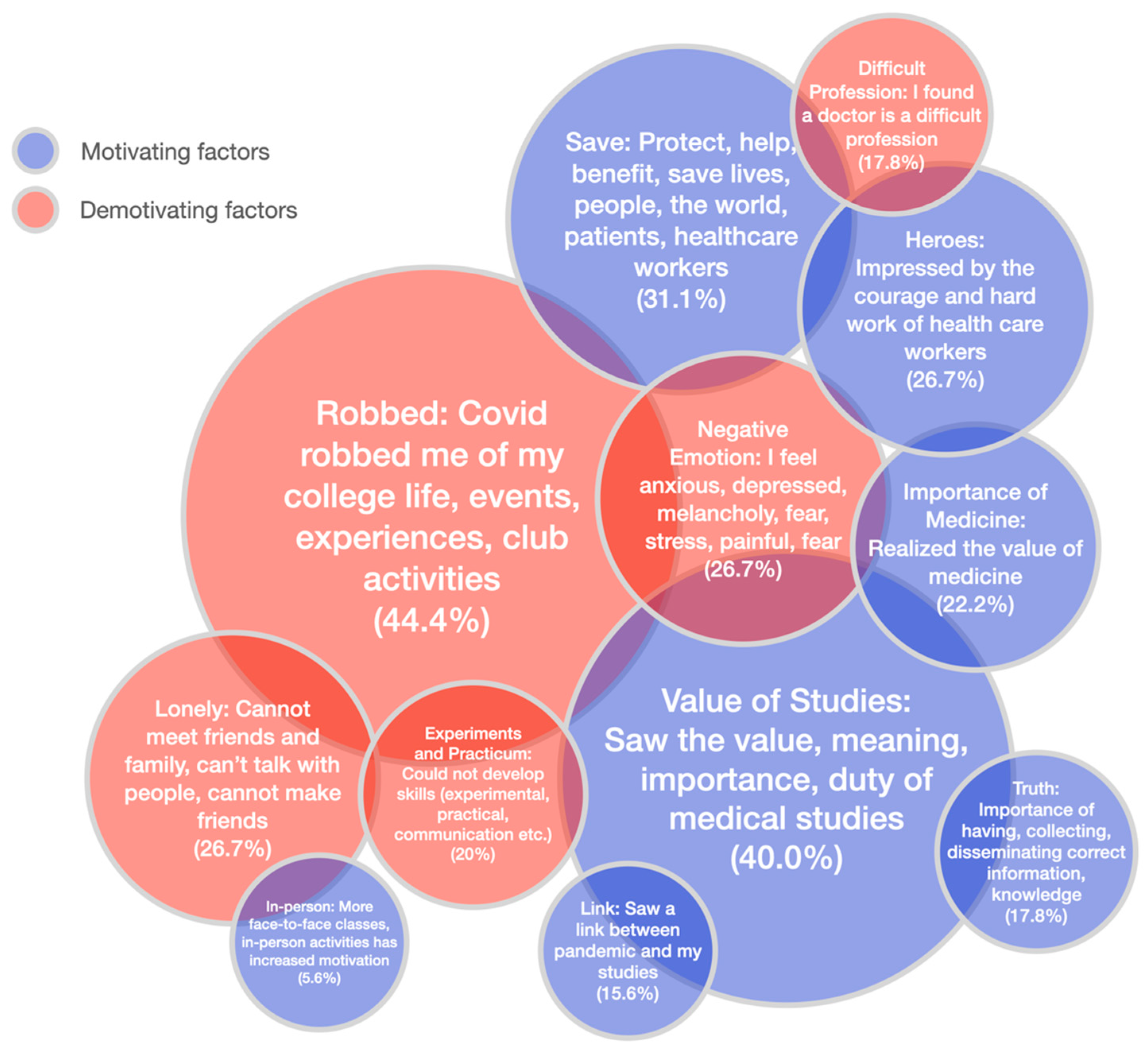

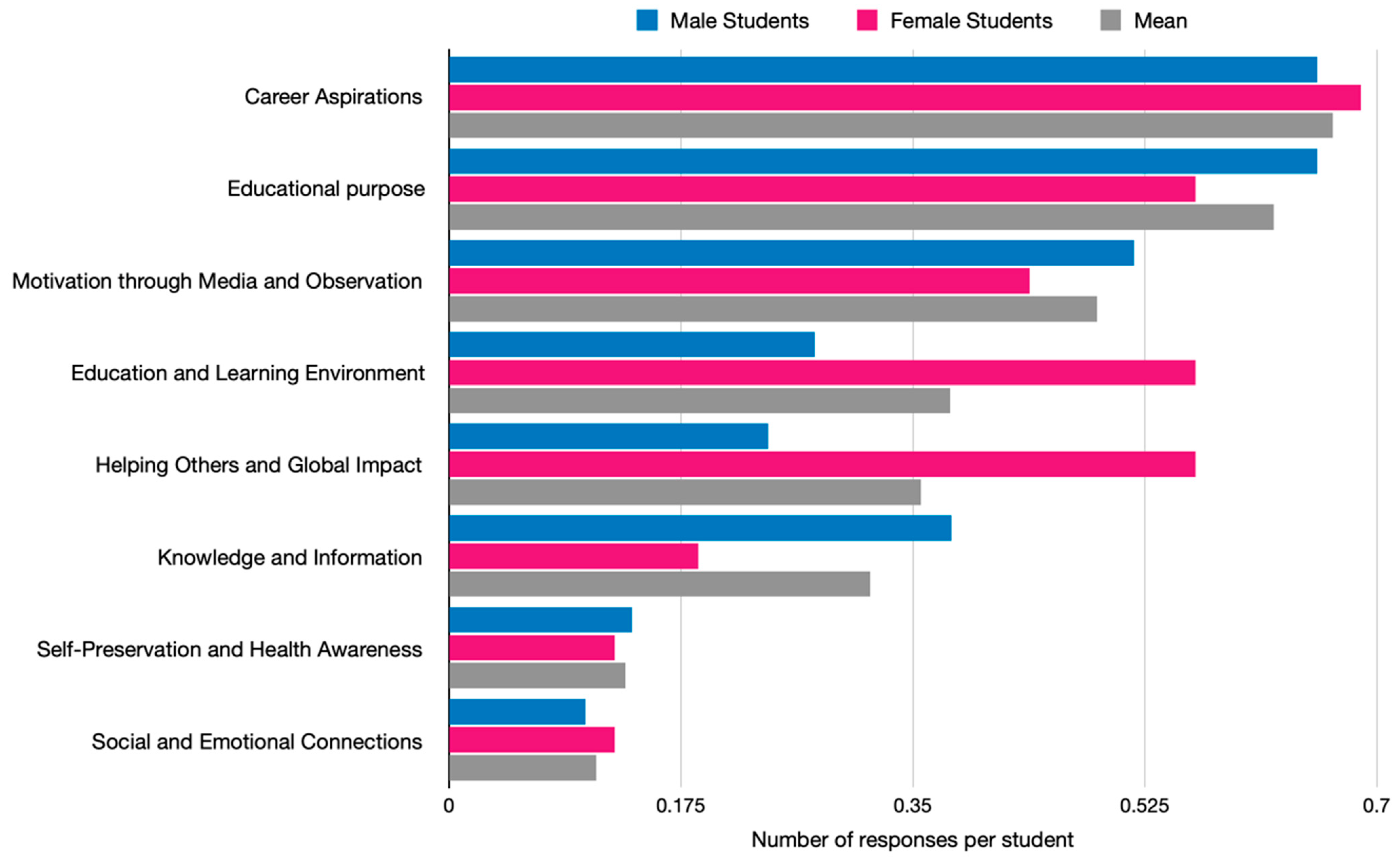

3.2.1. Coding Analysis of Motivational Factors

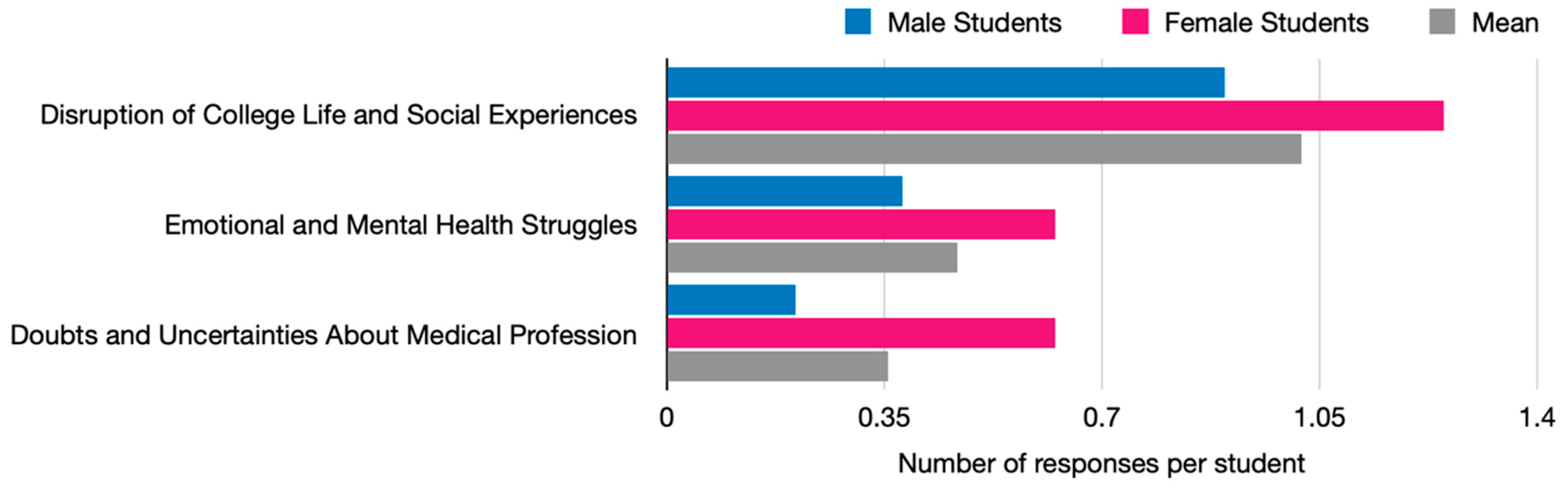

3.2.2. Coding Analysis of Demotivational Factors

3.3. Collaborative Autoethnography Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Medical Student Motivation during COVID-19

4.2. Demotivational Factors

4.3. Motivational Factors

4.4. Gender Differences in Medical Student Motivation

4.5. Educational Environment and Implications for Medical Curricula

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Results of the Sub-Analysis of the Interactions and Associations between the Factors

| Heroes | Total: 38 | |||||||||||

| Truth | 3 | Total: 22 | ||||||||||

| Save | 7 | 2 | Total: 40 | |||||||||

| In-Person | 1 | 1 | 3 | Total: 20 | ||||||||

| Link | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | Total: 19 | |||||||

| Value of Studies | 4 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 4 | Total: 50 | ||||||

| Importance of Medicine | 5 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 7 | Total: 32 | |||||

| Robbed | 3 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | Total: 41 | ||||

| Negative Emotions | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 6 | Total: 35 | |||

| Lonely | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 4 | Total: 32 | ||

| Experiments and Practicum | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 5 | Total: 31 | |

| Difficult Profession | 6 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Total: 25 |

| Heroes | Truth | Save | In-Person | Link | Value of Studies | Importance of Medicine | Robbed | Negative Emotions | Lonely | Experiments and Practicum | Difficult Profession |

Appendix B

Appendix B.1

Appendix B.2

Appendix B.3

References

- Cook, D.A.; Artino, A.R., Jr. Motivation to Learn: An Overview of Contemporary Theories. Med. Educ. 2016, 50, 997–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusurkar, R.A.; Ten Cate, T.J.; Vos, C.M.; Westers, P.; Croiset, G. How motivation affects academic performance: A structural equation modelling analysis. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2013, 18, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Li, S.; Zheng, J.; Guo, J. Medical students’ motivation and academic performance: The mediating roles of self-efficacy and learning engagement. Med. Educ. Online 2020, 25, 1742964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, R.D.; Manuel, R.S.; Borges, N.J.; Bott, E.M. Calling, vocational development, and well-being: A longitudinal study of medical students. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 79, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelaccia, T.; Viau, R. Motivation in medical education. Med. Teach. 2017, 39, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusurkar, R.A.; Ten Cate, T.J.; Van Asperen, M.; Croiset, G. Motivation as an independent and a dependent variable in medical education: A review of the literature. Med. Teach. 2011, 33, e242–e262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harries, A.J.; Lee, C.; Jones, L.; Rodriguez, R.M.; Davis, J.A.; Boysen-Osborn, M.; Kashima, K.J.; Krane, N.K.; Rae, G.; Kman, N.; et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical students: A multicenter quantitative study. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusurkar, R.A.; Croiset, G.; Ten Cate, O.T.J. Twelve Tips to Stimulate Intrinsic Motivation in Students through Autonomy-Supportive Classroom Teaching Derived from Self-Determination Theory. Med. Teach. 2011, 33, 978–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, C.A.; Harackiewicz, J.M.; Priniski, S.J.; Canning, E.A.; Tibbetts, Y.; Hyde, J.S. Promoting Persistence in the Biological and Medical Sciences: An Expectancy-Value Approach to Intervention. J. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 111, 1462–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricotta, D.N.; Huang, G.C.; Hale, A.J.; Freed, J.A.; Smith, C.C. Mindset Theory in Medical Education. Clin. Teach. 2019, 16, 159–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilcha, R.J. Effectiveness of virtual medical teaching during the COVID-19 crisis: Systematic review. JMIR Med. Educ. 2020, 6, e20963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, B.; Jegatheeswaran, L.; Minocha, A.; Alhilani, M.; Nakhoul, M.; Mutengesa, E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on final year medical students in the United Kingdom: A national survey. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, Z.; Wilcox, H.; Leung, L.; Dearsley, O. COVID-19 and the mental well-being of Australian medical students: Impact, concerns and coping strategies used. Australas. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 649–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Hao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; He, L.; et al. The prevalence and risk factors of mental problems in medical students during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 321, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arima, M.; Takamiya, Y.; Furuta, A.; Siriratsivawong, K.; Tsuchiya, S.; Izumi, M. Factors associated with the mental health status of medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study in Japan. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e043728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, Y.; Ochi, K.; Tokumasu, K.; Obika, M.; Hagiya, H.; Kataoka, H.; Otsuka, F. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the psychological distress of medical students in Japan: Cross-sectional survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e25232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahara, M.; Mashizume, Y.; Takahashi, K. Mental health crisis and stress coping among healthcare college students momentarily displaced from their campus community because of COVID-19 restrictions in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komasawa, N.; Terasaki, F.; Nakano, T.; Saura, R.; Kawata, R. A text mining analysis of perceptions of the COVID-19 pandemic among final-year medical students. Acute Med. Surg. 2020, 7, e576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruta, J.; Takayashiki, A.; Goto, R.; Maeno, T.; Ozone, S.; Maeno, T. Has novel coronavirus infection affected the professional identity recognised by medical students?—A historical cohort study. Asia Pac. Sch. 2023, 8, OA2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, M.; Nishiya, K.; Kaneko, K. Transition from undergraduates to residents: A SWOT analysis of the expectations and concerns of Japanese medical graduates during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayers, T.; Mathis, B.J.; Ho, C.K.; Morikawa, K.; Maki, N.; Hisatake, K. Factors affecting undergraduate medical science students’ motivation to study during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, P.H.; Scholz, M. Gender as an underestimated factor in mental health of medical students. Ann. Anat. 2018, 218, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukushima, K.; Fukushima, N.; Sato, H.; Yokota, J.; Uchida, K. Association between nutritional level, menstrual-related symptoms, and mental health in female medical students. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayers, T.; Mathis, B.J.; Maki, N.; Maeno, T. Japanese Medical Students’ English Language Learning Motivation, Willingness to Communicate, and the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. Med. Educ. 2023, 2, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, K.; Scacco, J.M. Content Analysis, Quantitative. In The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods; Matthes, J., Davis, C.S., Potter, R.F., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapadat, J.C. Ethics in autoethnography and collaborative autoethnography. Qual. Inq. 2017, 23, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, L.; Christensen-Strynø, M.B.; Frølunde, L. Thinking with autoethnography in collaborative research: A critical, reflexive approach to relational ethics. Qual. Res. 2022, 22, 761–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blalock, A.E.; Akehi, M. Collaborative autoethnography as a pathway for transformative learning. J. Transform. Educ. 2018, 16, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsby, E.R.; Davis, A.; Reilly, J.C. Collaborative autoethnography: Best practices for developing group projects. InSight J. Sch. Teach. 2021, 16, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Bailey, D. What are the barriers and support systems for service user-led research? Implications for practice. J. Ment. Health Train. Educ. Pract. 2010, 5, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, J.F.; Lesage, A.; Delorme, A.; Macaulay, A.C.; Salsberg, J.; Valle, C.; Davidson, L. User-led Research: A Global and Person-Centered Initiative. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2011, 13, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, A.; Thomas, P. User-led research and evidence-based medicine. Br. J. Psychiatry 2002, 180, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healey, M. Linking research and teaching to benefit student learning. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2005, 29, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, B.L. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences, 4th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, C.W. Other Than Counting Words: A Linguistic Approach to Content Analysis. Soc. Forces 1989, 68, 147–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, V.; de Moraes, A.G.; Khateeb, D.; Greenstein, Y.; Winter, G.; Chae, J.; Stewart, N.H.; Qadir, N.; Dangayach, N.S. Medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Chest 2021, 159, 1949–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turana, Y.; Primatanti, P.A.; Sukarya, W.S.; Wiyanto, M.; Duarsa, A.B.S.; Wratsangka, R.; Adriani, D.; Sasmita, P.K.; Budiyanti, E.; Anditiarina, D.; et al. Impact on medical education and the medical student’s attitude, practice, mental health, after one year of the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 843998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riboldi, I.; Capogrosso, C.A.; Piacenti, S.; Calabrese, A.; Lucini Paioni, S.; Bartoli, F.; Crocamo, C.; Carrà, G.; Armes, J.; Taylor, C. Mental health and COVID-19 in university students: Findings from a qualitative, comparative study in Italy and the UK. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong-Mensah, E.; Ramsey-White, K.; Yankey, B.; Self-Brown, S. COVID-19 and distance learning: Effects on Georgia State University school of public health students. Front. Public Health 2020, 547, 576227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, C.; Boente, C.; Zitouni, A.; Baelo, R.; Rosales-Asensio, E. Resilient Strategies for Internet-Based Education: Investigating Engineering Students in the Canary Islands in the Aftermath of COVID-19. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempski, P.; Arantes-Costa, F.M.; Kobayasi, R.; Siqueira, M.A.; Torsani, M.B.; Amaro, B.Q.; Nascimento, M.E.F.; Siqueira, S.L.; Santos, I.S.; Martins, M.A. Medical students’ perceptions and motivations during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metakides, C.; Pielemeier, L.; Lytras, T.; Mytilinaios, D.G.; Themistocleous, S.C.; Pieridi, C.; Tsioutis, C.; Johnson, E.O.; Ntourakis, D.; Nikas, I.P. Burnout and motivation to study medicine among students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1214320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadi, N.; Saleh, S.; Johnson, J.A.; Trinidade, A. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the lifestyle and behaviours, mental health and education of students studying healthcare-related courses at a British university. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dworkin, M.; Akintayo, T.; Calem, D.; Doran, C.; Guth, A.; Kamami, E.M.; Kar, J.; LaRosa, J.; Liu, J.C., Jr.; Perez Jimenez, I.N.; et al. Life during the pandemic: An international photo-elicitation study with medical students. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, S. Medical Student Education in the Time of COVID-19. JAMA 2020, 323, 2131–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TMS Collaborative. The perceived impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical student education and training—An international survey. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeilia, A.; Sotiropoulos, M.G.; Hanrahan, J.G.; Janga, D.; Dedeilias, P.; Sideris, M. Medical and surgical education challenges and innovations in the COVID-19 era: A systematic review. In Vivo 2020, 34 (Suppl. 3), 1603–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.; Nguyen, T.V. Motivation and preference in isolation: A test of their different influences on responses to self-isolation during the COVID-19 outbreak. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 200458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardekani, A.; Hosseini, S.A.; Tabari, P.; Rahimian, Z.; Feili, A.; Amini, M.; Mani, A. Student support systems for undergraduate medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic narrative review of the literature. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Lin, X.; He, L.; Freudenreich, T.; Liu, T. Impact of the perceived mental stress during the COVID-19 pandemic on medical students’ loneliness feelings and future career choice: A preliminary survey study. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 666588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passemard, S.; Faye, A.; Dubertret, C.; Peyre, H.; Vorms, C.; Boimare, V.; Auvin, S.; Flamant, M.; Ruszniewski, P.; Ricard, J.D. COVID-19 crisis impact on the next generation of physicians: A survey of 800 medical students. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrnes, Y.M.; Civantos, A.M.; Go, B.C.; McWilliams, T.L.; Rajasekaran, K. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical student career perceptions: A national survey study. Med. Educ. Online 2020, 25, 1798088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrel, M.N.; Ryan, J.J. The impact of COVID-19 on medical education. Cureus 2020, 12, e7492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krier, C.R.; Quinn, K.; Kaljo, K.; Farkas, A.H.; Ellinas, E.H. The effect of COVID-19 on the medical school experience, specialty selection, and career choice: A qualitative study. J. Surg. Educ. 2022, 79, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, L.P.; Dam, V.A.T.; Boyer, L.; Auquier, P.; Fond, G.; Tran, B.; Vu, T.M.T.; Do, H.T.; Latkin, C.A.; Zhang, M.W.; et al. Impacts of COVID-19 on career choices in health professionals and medical students. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byram, J.N.; Frankel, R.M.; Isaacson, J.H.; Mehta, N. The impact of COVID-19 on professional identity. Clin. Teach. 2022, 19, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Wu, H.; Zhou, W.; Shen, J.; Qiu, W.; Zhang, R.; Wu, J.; Chai, Y. Positive impact of COVID-19 on career choice in pediatric medical students: A longitudinal study. Transl. Pediatr. 2020, 9, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.Z.; Li, Z.J.; Chong, Y.M.; Xu, Y.; Fan, J.P.; Yang, Y.; Teng, Y.; Zhang, Y.W.; Zhang, W.C.; Zhang, M.Z.; et al. Chinese medical students’ interest in COVID-19 pandemic. World J. Virol. 2020, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiberman, J.A.; Nester, T.; Emrich, B.; Staley, E.M.; Bourassa, L.A.; Tsang, H.C. Coping with COVID-19: Emerging medical student clinical pathology education in the Pacific Northwest in the face of a global pandemic. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2021, 155, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, S.; Angeli, F.; Dhirar, N.; Singla, N.; Ruwaard, D. What motivates medical students to select medical studies: A systematic literature review. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, T.P.; Samudra, M.G.; Nashor, K.M.N.; Agustini, D.; Syakurah, R.A. Health professional student’s volunteering activities during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic literature review. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 797153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, M.H.V.; Ashcroft, J.; Alexander, L.; Wan, J.C.; Harvey, A. Systematic review of medical student willingness to volunteer and preparedness for pandemics and disasters. Emerg. Med. J. 2022, 39, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, V.; Quinton, N.D.; Bekker, H.L.; Roberts, T.E. Strategies and interventions for the involvement of real patients in medical education: A systematic review. Med. Educ. 2009, 43, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horsburgh, J.; Ippolito, K. A skill to be worked at: Using social learning theory to explore the process of learning from role models in clinical settings. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birden, H.; Glass, N.; Wilson, I.; Harrison, M.; Usherwood, T.; Nass, D. Teaching professionalism in medical education: A Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) systematic review. Med. Teach. 2013, 35, e1252–e1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swick, H.M.; Szenas, P.; Danoff, D.; Whitcomb, M.E. Teaching professionalism in undergraduate medical education. JAMA 1999, 282, 830–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, E.A.; Maestas, R.R.; Fryer-Edwards, K.; Wenrich, M.D.; Oelschlager, A.M.A.; Baernstein, A.; Kimball, H.R. Professionalism in medical education: An institutional challenge. Acad. Med. 2006, 81, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, S.; Southgate, L. Professionalism in medical education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2007, 23, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesema, N.; Collison, M.; Luo, C. Using medical students as champions against misinformation during a global pandemic. Acad. Med. 2022, 97, 1103–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, V.; Brunelli, L.; Conte, A.; Valdi, G.; Guelfi, M.R.; Masoni, M.; Anelli, F.; Arnoldo, L. A Web Tool to Help Counter the Spread of Misinformation and Fake News: Pre-Post Study Among Medical Students to Increase Digital Health Literacy. JMIR Med. Educ. 2023, 9, e38377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baluszek, J.B.; Brønnick, K.K.; Wiig, S. The relations between resilience and self-efficacy among healthcare practitioners in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic—A rapid review. Int. J. Health Governance 2023, 28, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finstad, G.L.; Giorgi, G.; Lulli, L.G.; Pandolfi, C.; Foti, G.; León-Perez, J.M.; Cantero-Sánchez, F.J.; Mucci, N. Resilience, coping strategies and posttraumatic growth in the workplace following COVID-19: A narrative review on the positive aspects of trauma. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buddeberg-Fischer, B.; Klaghofer, R.; Abel, T.; Buddeberg, C. The Influence of Gender and Personality Traits on the Career Planning of Swiss Medical Students. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2003, 133, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amerio, A.; Bertuccio, P.; Santi, F.; Bianchi, D.; Brambilla, A.; Morganti, A.; Odone, A.; Costanza, A.; Signorelli, C.; Aguglia, A.; et al. Gender differences in COVID-19 lockdown impact on mental health of undergraduate students. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 813130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zis, P.; Artemiadis, A.; Bargiotas, P.; Nteveros, A.; Hadjigeorgiou, G.M. Medical studies during the COVID-19 pandemic: The impact of digital learning on medical students’ burnout and mental health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guse, J.; Heinen, I.; Kurre, J.; Mohr, S.; Bergelt, C. Perception of the study situation and mental burden during the COVID-19 pandemic among undergraduate medical students with and without mentoring. GMS J. Med. Educ. 2020, 37, Doc72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibaut, F.; van Wijngaarden-Cremers, P.J.M. Women’s Mental Health in the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Glob. Womens Health 2020, 1, 588372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauhanen, L.; Wan Mohd Yunus, W.M.A.; Lempinen, L.; Peltonen, K.; Gyllenberg, D.; Mishina, K.; Gilbert, S.; Bastola, K.; Brown, J.S.L.; Sourander, A. A Systematic Review of the Mental Health Changes of Children and Young People Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 32, 995–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Rosa, V.L.; Commodari, E. University Experience during the First Two Waves of COVID-19: Students’ Experiences and Psychological Wellbeing. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 1477–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Sujan, M.S.H.; Tasnim, R.; Sikder, M.T.; Potenza, M.N.; van Os, J. Psychological Responses During the COVID-19 Outbreak Among University Students in Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0245083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Qu, Y.; Sun, H.; Huo, H.; Yin, H.; You, D. Mental Health Among Medical Students During COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 846789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Ping, S.; Liu, X. Gender Differences in Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Among College Students: A Longitudinal Study from China. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 263, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eleftheriou, A.; Rokou, A.; Arvaniti, A.; Nena, E.; Steiropoulos, P. Sleep Quality and Mental Health of Medical Students in Greece During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 775374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villadsen, A.; Patalay, P.; Bann, D. Mental Health in Relation to Changes in Sleep, Exercise, Alcohol, and Diet During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Examination of Four UK Cohort Studies. Psychol. Med. 2023, 53, 2748–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Candia, C.; Risco Miranda, C.; Durán-Agüero, S.; Candia Johns, P.; Díaz-Vásquez, W. Association Between Diet, Mental Health and Sleep Quality in University Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2023, 35, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamees, D.; Peterson, W.; Patricio, M.; Pawlikowska, T.; Commissaris, C.; Austin, A.; Davis, M.; Spadafore, M.; Griffith, M.; Hider, A.; et al. Remote learning developments in postgraduate medical education in response to the COVID-19 pandemic—A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 71. Med. Teach. 2022, 44, 466–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhar, P.; Rocks, T.; Samarasinghe, R.M.; Stephenson, G.; Smith, C. Augmented reality in medical education: Students’ experiences and learning outcomes. Med. Educ. Online 2021, 26, 1953953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, M.C.; Walsh, B.M. Telesimulation-based education during COVID-19. Clin. Teach. 2021, 18, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahart, E.R.; Gilmer, L.; Tenpenny, K.; Krase, K. Improving Resident Well-Being: A Narrative Review of Wellness Curricula. Postgrad. Med. J. 2023, 99, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, L.; Morgan, H.; Buery-Joyner, S.D.; Craig, L.B.; Everett, E.N.; Forstein, D.A.; Graziano, S.C.; Hampton, B.S.; McKenzie, M.L.; Page-Ramsey, S.M.; et al. To the Point: A Prescription for Well-Being in Medical Education. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 221, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romcevich, L.E.; Reed, S.; Flowers, S.R.; Kemper, K.J.; Mahan, J.D. Mind-Body Skills Training for Resident Wellness: A Pilot Study of a Brief Mindfulness Intervention. J. Med. Educ. Curric. Dev. 2018, 5, 2382120518773061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Steele, K.; Singh, L. Combining the Best of Online and Face-to-Face Learning: Hybrid and Blended Learning Approach for COVID-19, Post Vaccine, & Post-Pandemic World. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2021, 50, 140–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.J. Moving Forward: Embracing Challenges as Opportunities to Improve Medical Education in the Post-COVID Era. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Code, Explanation, Example Statement | Male n (%) | Female n (%) | Total n (%) | p-Value (Effect Size) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Career Aspirations | Importance of Medicine: Realized the value of medicine: “The spread of the coronavirus has reminded me of the importance of medicine”. | 5 (17.2) | 5 (31.3) | 10 (22.2) | 0.279 (0.448) |

| Good Doctor: Want to be a good doctor: “This situation makes me more motivated to study medicine. I want to study medicine more, work as a good doctor, and help many people in need”. | 4 (13.8) | 2 (12.5) | 6 (13.3) | 0.516 (0.370) | |

| Contribute: Hope to contribute to medicine, drug or vaccine development in the future: “This corona has strengthened my desire to contribute to people as a medical worker or researcher, and has motivated me to study medicine”. | 2 (6.9) | 4 (25.0) | 6 (13.3) | 0.091 (0.544) | |

| Determined: COVID made me more determined to become a medical doctor: “After COVID-19, I have a strong feeling that I should be a medical professional”. | 3 (10.3) | 0 (0) | 3 (6.7) | 0.258 (0.456) | |

| Rewarding: Doctor’s job is rewarding: “Doctors’ job is a rewarding job. I want to get to feel rewarding in my working, so the [pandemic] situation gives me some motivation”. | 2 (6.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.4) | 0.410 (0.403) | |

| Grow: Grow as a person, medical worker, doctor: “I would like to study at this university so that I can grow as a person as well as medical knowledge”. | 1 (3.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.2) | 0.590 (0.346) | |

| Shortage: Shortage of medical workers, healthcare system problems: “COVID-19 especially had a big impact on the medical setting. Even though medical supplies, beds, and human resources were not enough, doctors and nurses had to work to treat patients”. | 1 (3.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.2) | 0.644 (0.328) | |

| Vision: Can visualize the work of a medical doctor/vision for the future: “COVID-19 gave me an even clearer purpose of studying medical science and the image of the ideal doctor”. | 1 (3.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.2) | 0.644 (0.328) | |

| Category total: | 19 (65.5) | 11 (68.8) | 30 (66.7) | 0.328 § (0.651) | |

| Educational Purpose | Value of Studies: Saw the value, meaning, importance, duty of medical studies: “I began to realize that, as a medical student, I had the responsibility to acquire knowledge about the current medical care situation and think about what we can do right now as students”. | 12 (41.4) | 6 (37.5) | 18 (40) | 0.799 (0.262) |

| Link: Saw a link between pandemic and my studies: “As we learned more about the virus, we were motivated to learn more about medicine. Actually, experiencing a viral epidemic made me understand why viruses are so dangerous”. | 6 (20.7) | 1 (6.3) | 7 (15.6) | 0.202 (0.480) | |

| Opportunity: I have more chances to study medicine than other people as a medical student: “I’m medical student and have an opportunity to learn medicine in detail, so I would like to make a good use of the chance”. | 1 (3.4) | 2 (12.5) | 3 (6.7) | 0.285 (0.446) | |

| Category total: | 19 (65.5) | 9 (56.3) | 28 (62.2) | 0.700 § (0.349) | |

| Motivation through Media and Observation | Heroes: Impressed by the courage and hard work of health care workers: “When I see on TV that doctors in the field are risking their lives to deal with corona, I feel a strong desire to become a full-fledged doctor and fight COVID-19” | 7 (24.1) | 5 (31.3) | 12 (26.7) | 0.610 (0.339) |

| Media Good: Watching the news, TV about COVID, medical field: “As a result of this pandemic, medical care has been covered more and more in the mass media, and I have become more interested in medical care than ever before”. | 5 (17.2) | 1 (6.3) | 6 (13.3) | 0.408 (0.404) | |

| Innovation: Impressed by advances in medicine, vaccines: “Recently, the vaccine was made and taken. From my perspective, this is great job of researchers. I am impressed their effort and hope that we can overcome COVID-19”. | 3 (10.3) | 1 (6.3) | 4 (8.9) | 0.592 (0.345) | |

| Category total: | 15 (51.7) | 7 (43.8) | 22 (48.9) | 0.700 § (0.349) | |

| Education and Learning Environment | In-person: More face-to-face classes, in-person activities has increased motivation: “Now, I am more motivated to study medicine. We had our second semester class face to face and I was able to make friends and study with them”. | 3 (10.3) | 4 (25) | 7 (15.6) | 0.191 (0.485) |

| Online Good: Online classes are good: “The pandemic has given me a flexible environment for studying, with a great help of the university staff and lecturers. Due to enhancement of online system, students could learn from streamed video which was useful for revision, leading to a better understanding”. | 3 (10.3) | 2 (12.5) | 5 (11.1) | 0.715 (0.301) | |

| Time: Had time to reflect on my future, study more, more free time: “I think my motivation for studying has increased because I have more free time”. | 2 (6.9) | 1 (6.3) | 3 (6.7) | 0.715 (0.301) | |

| Encouraged: When I saw my friends studying hard, I was encouraged: “My motivation to study has been more motivated by classmates because they are so excellent that I always feel that I should study hard to catch up with them”. | 0 (0) | 2 (12.5) | 2 (4.4) | 0.121 (0.339) | |

| Category total: | 8 (27.6) | 9 (56.3) | 17 (37.8) | 0.147 § (0.775) | |

| Helping Others and Global Impact | Save: Protect, help, benefit, save lives, people, the world, patients, healthcare workers: “I want to help many people working at medical setting, but I cannot do anything for COVID-19 patients. In order to help many patients in the future, I should study medicine hard now”. | 6 (20.7) | 8 (50) | 14 (31.1) | 0.042 * (0.569) |

| Developing Countries: Help people in poor, developing countries, address disparities in medical care: “I was shocked by the terrible disparity with areas where medical care was not available. Medical care must be something that people can receive “equally” and “fairly”. I think it is necessary to solve these problems in the future”. | 1 (3.4) | 1 (6.3) | 2 (4.4) | 0.590 (0.346) | |

| Category total: | 7 (24.1) | 9 (56.3) | 16 (35.6) | 0.078 (0.965) | |

| Knowledge and Information | Truth: Importance of having, collecting, disseminating correct information, knowledge: “Learning a lot of medical knowledge, I can become to judge whether a medical news is true or false. It is essential to pick the true information up and decide our behavior by ourselves”. | 6 (20.7) | 2 (12.5) | 8 (17.8) | 0.516 (0.370) |

| Scientific Interest: Pandemic made me interested in medical science, virology, infection biology, new research fields: “Through the COVID-19 pandemic, I want to study virology and immunology”. | 5 (17.2) | 1 (6.3) | 6 (13.3) | 0.292 (0.443) | |

| Category total: | 11 (37.9) | 3 (18.8) | 14 (31.1) | 0.372 § (0.415) | |

| Self-Preservation and Health Awareness | Protection: Realized the importance of protecting myself, doing what I can to curb the pandemic: “I hope that the COVID-19 pandemic will be over by the time I start working as a doctor, but there is a great possibility that another infectious disease will spread. I think I need to learn well now so that I can protect myself and work for the patients in such a situation”. | 4 (13.8) | 1 (6.3) | 5 (11.1) | 0.408 (0.404) |

| Life: Realized the importance of life, health: “The pandemic has had a positive impact on my motivation mainly because it made me realize that health is the core of our social life”. | 0 (0) | 1 (6.3) | 1 (2.2) | 0.356 (0.421) | |

| Category total: | 4 (13.8) | 2 (12.5) | 6 (13.3) | 0.903 § (0.176) | |

| Social and Emotional Connections | Communication: Realized the importance of communicating, interaction, relationships with friends: “Thanks to the environment in which we are forced to take what is called “social distance,” I can experience first-hand the importance of being with and interacting with others”. | 1 (3.4) | 2 (12.5) | 3 (6.7) | 0.285 (0.446) |

| New Friends: I could make other friends because of the pandemic: “COVID-19 helped me to have wide and deep relationship with my friends”. | 2 (6.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.4) | 0.410 (0.403) | |

| Category total: | 3 (10.3) | 2 (12.5) | 5 (11.1) | 0.826 § (0.246) |

| Category | Code, Explanation, Example Statement | Male n (%) | Female n (%) | Total n (%) | p-Value (Effect Size) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disruption of College Life and Social Experiences | Robbed: COVID robbed me of my college life, events, experiences, club activities: “I think that the COVID-19 pandemic has robbed me of the college life I envisioned and deprived me of my motivation to study”. | 14 (48.3) | 6 (37.5) | 20 (44.4) | 0.486 (0.379) |

| Lonely: Cannot meet friends and family, can’t talk with people, cannot make friends: “The complete isolation, to some extent, made me feel lonely making it harder to maintain my mental health”. | 7 (24.1) | 5 (31.3) | 12 (26.7) | 0.606 (0.341) | |

| Experiments and Practicum: Could not develop skills (experimental, practical, communication etc.): “Some of the practical training specific to medical school was cancelled. For example, those held in hospitals. This led to a decrease in our motivation. In addition, instead of doing this practical training, we were shown videos and made to write reports on the training we did not do, which was just painful. Also, in the practicals where we had to do experiments, we were given only the data to discuss without actually doing the experiments”. | 2 (6.9) | 7 (43.8) | 9 (20) | 0.006 * (0.702) | |

| Online Bad: Online classes and studying at home were bad, demotivating, lack of in-person class interaction: “I think I lost a little bit of motivation in the online classes”. | 3 (10.3) | 2 (12.5) | 5 (11.1) | 0.592 (0.345) | |

| Category total: | 26 (89.7) | 20 (125) | 46 (102.2) | 0.486 § (0.523) | |

| Emotional and Mental Health Struggles | Negative Emotion: I feel anxious, depressed, melancholy, fear, stress, painful, fear: “I have never experienced such a life-threatening pandemic before, so I feel very scared”. | 7 (24.1) | 5 (31.3) | 12 (26.7) | 0.606 (0.341) |

| Helpless: I felt helpless and frustrated as a medical student: “The COVID19 crisis once made me less motivated to study because it seemed to me that there is nothing we can do to cure seriously ill patients and improve the situation. I felt that it is helpless and there is no meaning to study hard”. | 2 (6.9) | 4 (25) | 6 (13.3) | 0.107 (0.532) | |

| Media Bad: Watching the news made me anxious: “When I first heard about the pandemic through the media, I was taken aback and scared. The media mentioned the threatening situation our country’s medical care system is facing and the risks healthcare workers are taking”. | 1 (3.4) | 1 (6.3) | 2 (4.4) | 0.590 (0.346) | |

| Mask: Wearing a mask is hard: “The fact that I have to wear a mask all the time is also stressful for me”. | 1 (3.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.2) | 0.644 (0.328) | |

| Category total: | 11 (37.9) | 10 (62.5) | 21 (46.7) | 0.686 § (0.361) | |

| Doubts and Uncertainties About Medical Profession | Difficult Profession: I found a doctor is a difficult profession: “Healthcare workers including doctors have to take care of infected patients. In fact, it is a risky job. I became anxious about my life as a doctor. Possibly, I may be transferred illness in the hospital. I realized difficulty of working as a health care worker”. | 2 (6.9) | 6 (37.5) | 8 (17.8) | 0.017 * (0.649) |

| Limitations: I became aware of the limitations of medicine, medical science: “I felt that the threat of infectious diseases is very real. At the same time, by being exposed to the threat of infectious diseases, I became aware of the powerlessness of human beings and the limitations of medical science”. | 2 (6.9) | 3 (18.8) | 5 (11.1) | 0.233 (0.466) | |

| Discrimination: Experienced, witnessed discrimination, criticism of healthcare workers, medical students: “I heard the news that some healthcare workers left their hospitals because of harmful rumors or hard schedule. They are working so hard for people suffering from illness and pain, however, at the same time, the same people damage them, not appreciating for their hard working”. | 2 (6.9) | 1 (6.3) | 3 (6.7) | 0.715 (0.301) | |

| Category total: | 6 (20.7) | 10 (62.5) | 16 (35.6) | 0.062 *§ (1.005) |

| Theme | Explanation | Example Sentences from the Essays |

|---|---|---|

| Impact on Education | All three essays discuss the significant impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on education. They mention shifts to online learning, cancellations of hands-on experiences, and disruptions to the usual academic routines | “All classes, including new student orientation, shifted online, and hands-on hospital experiences were canceled. The continuation of the pandemic, which had already influenced my high school experience, left me feeling deprived of numerous opportunities”. (Appendix B.1) |

| Loneliness and Isolation | Each essay touches upon feelings of loneliness and isolation experienced by the authors during the pandemic, such as absence of classmates, solitude leading to introspection, and empathy towards others’ anxiety and loneliness | “I had a harder time focusing on online lectures without having my classmates nearby to have a little side conversation with. It was quite lonely”. (Appendix B.2) |

| Career Reflection | The essays reflect on the authors’ career aspirations and how the pandemic influenced their perceptions of their chosen paths. They discuss gaining clarity about their goals and motivations, as well as discovering alternative career paths related to healthcare beyond traditional medical practice. | “I realized that there were a variety of career paths to save people’s lives, such as basic medical scientists and social welfare researchers. Through media, I not only learned about the serious situations around the world but also witnessed the achievements in vaccine development and the critical role of public health systems. These revelations helped me clarify what I wanted to learn for 6 years of medical school”. (Appendix B.1) |

| Resilience and Adaptability | Despite the challenges presented by the pandemic, all three authors demonstrate resilience and adaptability in their responses. They find ways to cope with the changes, whether through introspection, seeking out new opportunities, or finding solace in outdoor activities. | “As a healthy 22-year-old, it forced me to adapt to unforeseen circumstances, building resilience for future uncertainties. While some classmates reported feeling lost or demotivated, the pandemic became, for me, a catalyst for self-discovery”. (Appendix B.3) |

| Positive Outcomes | Despite the difficulties, each essay also highlights positive outcomes or lessons learned from the pandemic experience. These include increased motivation to pursue medicine, appreciation for the importance of accurate information, and deeper understanding of the role of healthcare workers. | “It was inspiring seeing the hard work of medical workers. However, the main message I got from the media was that medicine isn’t perfect and you need to be prepared to become a doctor. This sense of danger increased my motivation for studying. It led me to recognize that studying is a must, but I also needed to grow as a person to become a true doctor”. (Appendix B.2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mayers, T.; Okamura, Y.; Kanaji, M.; Shimoda, T.; Maki, N.; Maeno, T. Medical Student Voices on the Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Motivation to Study: A Mixed-Method Qualitative Study. COVID 2024, 4, 1485-1512. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4090105

Mayers T, Okamura Y, Kanaji M, Shimoda T, Maki N, Maeno T. Medical Student Voices on the Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Motivation to Study: A Mixed-Method Qualitative Study. COVID. 2024; 4(9):1485-1512. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4090105

Chicago/Turabian StyleMayers, Thomas, Yui Okamura, Mai Kanaji, Tomonari Shimoda, Naoki Maki, and Tetsuhiro Maeno. 2024. "Medical Student Voices on the Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Motivation to Study: A Mixed-Method Qualitative Study" COVID 4, no. 9: 1485-1512. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4090105

APA StyleMayers, T., Okamura, Y., Kanaji, M., Shimoda, T., Maki, N., & Maeno, T. (2024). Medical Student Voices on the Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Motivation to Study: A Mixed-Method Qualitative Study. COVID, 4(9), 1485-1512. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid4090105