1. Introduction

The economic consequences of the recent surge in international migration are increasingly dominating political debates on [im]migration policy. Despite passionate political debates, our understanding of the economic consequences of migration remains inadequate. Foreign direct investment (FDI) research is thought to be the domain of economists and financial analysts. Many economies rely heavily on FDI and remittances from migrants to fund their fiscal budgets. However, governments are seen to prioritise attracting FDI and technology transfers to serve as a conduit for a significant source of revenue for businesses [

1]. There is a dearth of research on the relationship between migration and FDI. Buch et al. [

2] and Bhattacharya and Groznik [

3] discovered a correlation between migration and FDI. Kugler and Rapoport [

4], in their article, found a negative correlation between the two. Despite extensive research into the influence of various factors, the more subtle connections and feedback mechanisms that have built the global economy have gotten scant attention. The effect of migration on FDI is one such connection that merits consideration.

Migration has been an area of geo-demographic domain, while FDI is an economic one. FDI and migration are regarded as risk-averse strategies in developing countries such as India. For example, as immigrants in Spain grow, Spanish imports and exports to and from the countries of origin grow. This relationship endures over time and influences migration patterns. It has been, for example, demonstrated that FDI and remittances sent by Spaniards have an inverse relationship with emigration from Spain. As the economy weakens, FDI declines, while the number of Spaniards moving to the USA and sending money home increases.

Since the COVID-19 outbreak in early 2020, the world has been experiencing major health, social, political and economic consequences [

5,

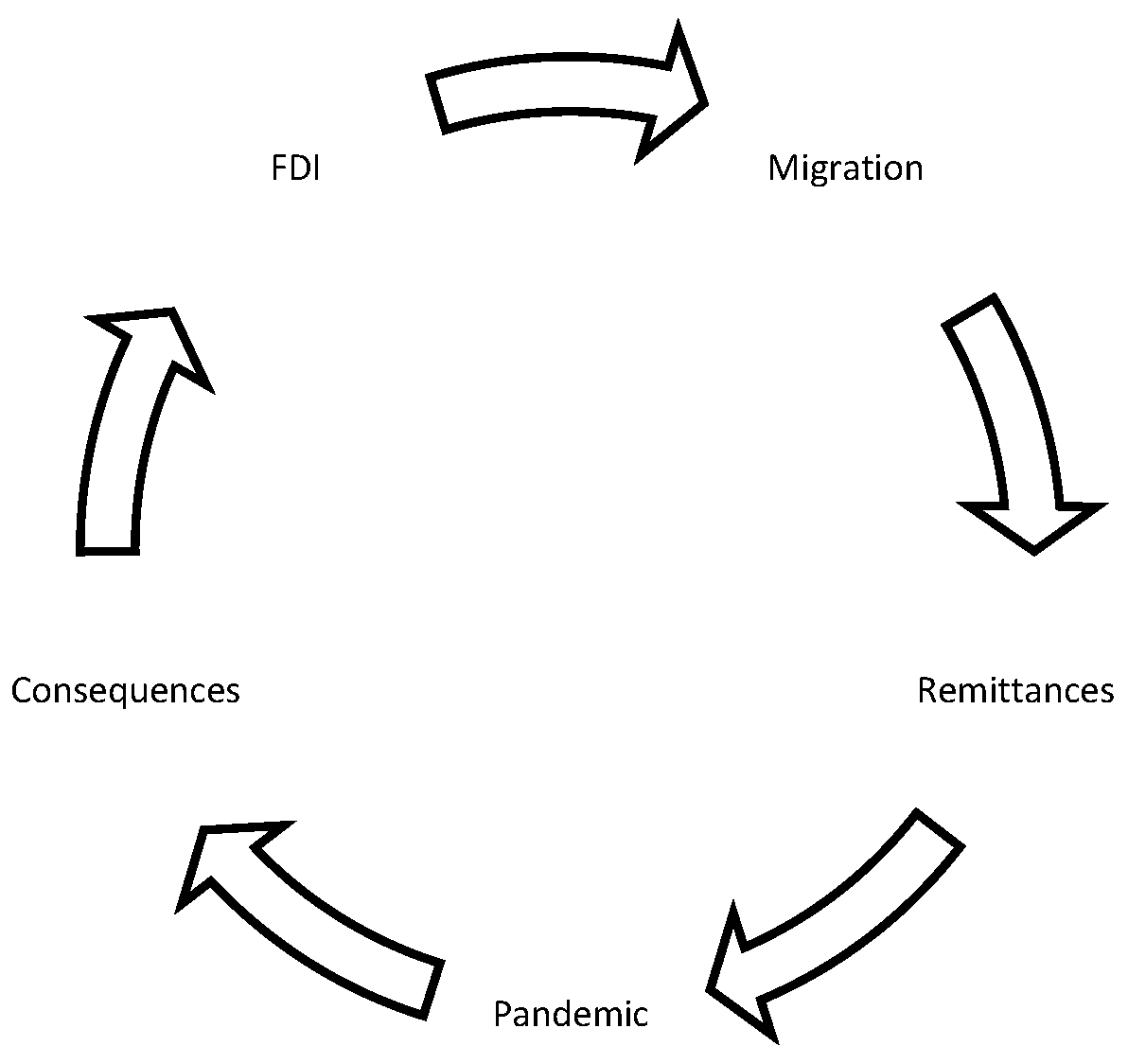

6]. Apparently, these three aspects (migration, FDI and the pandemic, (see

Figure 1). may sound like an incoherent triad. This article explores the influence of COVID-19 epidemic on the South Asian economy, especially India given the predicted decline in FDI and international funding. The flow of FDI and foreign aid from developed to developing countries would obviously be affected as the economies of the large, industrialised countries suffered. Hence, in this article, we attempt to uncover relationships among these three in relation to India’s migration and FDI and the impact of the pandemic.

The economic climate has a significant impact on the spread of a pandemic. As far as we can know, worldwide pandemics have had significant economic effects at various times throughout history. For example, the SARS epidemic impacted China and Southeast Asia [

7,

8]. Numerous places were gripped by SARS-related panic, which hindered economic growth, job creation, and a range of other ordinary social activities [

7]. East Asia incurred a cost of between USD 20 billion and USD 25 billion as a result of SARS [

7]. FDI and exports were both negatively impacted by the SARS outbreak, which had a long-lasting effect on the Chinese economy. Foreign tourist visits were 25% lower in July 2003 than in July 2002. The number of new investment contracts signed during those months fell precipitously [

7].

Governments worldwide appear to have failed in their efforts to reduce the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. FDI into emerging and developing economies has been badly affected by the COVID-19 epidemic’s impact. According to the UNCTAD, between 30% and 40% of global FDI flows were anticipated to drop between 2020 and 2021. Developing and underdeveloped countries face the brunt of the decline in FDI inflows [

9].

In the first six months following the advent of COVID-19, investor concern was evident in all major areas of FDI. For instance, greenfield project announcements decreased by 37 percent, international mergers and acquisitions decreased by 15 percent, and cross-border project financing announcements decreased by 25 percent [

10], making debates concerning the impact of COVID-19 on FDI relevant. However, the characteristics of OECD and emerging states that participate in international financial markets are significantly distinct [

10]. The lockdown precautions had differing effects on various types of businesses.

This article is organised in the following order: At the outset, we explored FDI, migration, and COVID-19, and we also examined how pandemics affect global economy. Following that, we outline the objectives and methods of our study. Then, we have examined FDI in the context of migration as well as the impact of COVID-19 on FDI flow and its relationship with labour mobility. Given our research’s focus on India, the following section of this study examines the relationships between these three concepts in India. Finally, we reach a conclusion.

2. Objectives and Methods

No research has been performed to date to prove that the COVID-19 pandemic is impacting FDI influx to South Asia, especially to India, because of the migratory (in/out) labour flow.

Studies show that pandemics tend to reduce FDI flow. The study of Anuchitworawong and Thampanishvong [

11] found that more severe natural disasters reduce FDI to Thailand. Multinational businesses (MNCs) weigh the risks of entering a new foreign market, including natural calamities [

12]. This pandemic has an impact on MNCs’ investment decisions and FDI flows as well [

13]. We attempt to figure out how the epidemic in South Asian economies, especially India, has affected the relationship between FDI and labour migration.

According to Hoxhaj et al. [

14], foreign capital inflows and the employment of skilled foreign workers are highly complementary. Our research indicates that FDI and skilled migration to India operate in tandem. Foreign firms increase the flow of human capital to their investment locations through the recruitment of foreign skilled personnel. A dearth of skilled labour in the destination country may necessitate the employment of more overseas workers. In nations with an abundance of skilled labour, international corporations favour native workers over imported ones. This demonstrates that when international companies are able to identify the appropriate talent in the local labour market, they can replace foreign workers with local ones.

This section focuses mainly on the methodological approaches to this research. A review of the past one and half years of research on COVID-19 and migration on the web was carried out. The data for this study came from secondary sources. We conducted substantial ‘Internet research’ [

15] that resulted in the discovery of a variety of online publications, documents, and newspaper articles on FDI, migration, and COVID-19. Internet research enabled us to collect secondary data on the economic impact that COVID-19 restrictions are having on poor countries. Additionally, we conducted in-depth assessments of the available literature on FDI, COVID-19, and their long-term effects on migrants, labour mobility, and economies worldwide.

2.1. Migration, FDI and COVID-19

FDI is critical to India’s economic growth and development. FDI in India contributes to long-term economic growth and development in two ways: by creating new jobs and expanding current manufacturing enterprises. For instance, FDI was concentrated in the computer, software, and hardware industries, as well as the pharmaceuticals and medications industry. On the other hand, the banking and insurance industries contribute to the stability of the Indian economy and the growth of the foreign currency market. Due to the fact that FDI always helps to create jobs in a country and also promotes small businesses, Vyas [

16] feels that this investment approach contributes to the country’s global image improvement. The term foreign direct investment (FDI) refers to an entity resident in another economy (known as a direct investor) seeking long-term interest, implying a long-term relationship between the direct investor and the direct investment firm as well as a significant degree of investor influence over the receiving enterprise’s management [

17].

FDI comes in a variety of forms, but the most usual is the acquisition of a substantial stake in a foreign company. Due to India’s restrictive and cumbersome approach to FDI, FDI into India declined by 26% in 2021 from the previous year. Additionally, India afterwards rebounded the flow in FDI due in part to the absence of substantial acquisitions. According to official data, the amount was anticipated to be USD 48.5 billion in October 2021 which was constant from April to October 2021. Inflows of FDI into India totalled USD 42.9 billion in the first half of 2022. Despite the current economic condition, studies indicate that inflows have not diminished. According to the government, the record number of deals struck this year (2022) has aided in maintaining the inflow. There was a significant increase over 2013′s total foreign investment of nearly USD 35 billion.

COVID-19 disruptions were predicted to have a long-term impact on migration [

18]. In the near future, individuals who travel to and from work may be unable to do so unless they qualify for an exemption (such as scientists, doctors, journalists, and politicians). This will have a profound effect on individuals, businesses, and even food security. Families already struggling to navigate immigration and visa systems may find themselves separated for an entirely new reason, as the majority of international migrants remains unable to return home. Businesses may accelerate the development of automation capabilities in response to current and future quarantines or “stay at home” orders [

19], thereby rapidly eliminating some occupations traditionally occupied by migrants. Preventing migrants from traveling to agricultural fields has far-reaching effects on the global food supply.

As a direct result of the border closure and recession, millions of jobs were lost globally, with migrant workers suffering the greatest losses across all areas [

20]. In most industries, COVID-19 layoffs disproportionately affected migrants, the majority of whom were on temporary visas. As a result, global inequality increased dramatically. Since the start of COVID-19, more than 160 million people have slipped into poverty due to decreased international trade and fewer foreign visitors. Meanwhile, during this pandemic, nearly daily millionaires have been created [

21]. The wealth of the 22 richest men in the world exceeds that of the entire population of Africa. In fact, the long-term migration effects of the epidemic are anticipated to aggravate global inequality.

Economic repercussions are uneven, with negative demand shocks concentrated in the economies hardest hit by COVID-19 and supply chain disruptions felt most acutely in economies reliant on FDI, remittances and global value chains. Investment’s influence will become even more tightly concentrated in the future. The bulk of low-skilled migrant workers are unable to work remotely [

22]. Due to the fact that low-income individuals must commute to work, their risk of catching and transmitting COVID-19 is increased [

20]. Millions of people who depend on daily labour in the informal sector were forced to choose between contracting an infection or starving to death due to their deplorable living conditions. Camp residents (migrants, refugees, IDPs, and stateless individuals) and slum dwellers are significantly more revealing. They will spend the rest of their lives imprisoned in tight, dark, and damp conditions [

23,

24].

Capital expenditures by MNEs and their worldwide affiliates has hindered with the onset of COVID-19. As manufacturing facilities are closed or operated at reduced capacity, investment in new physical assets and expansions got halted. COVID-19 is having a large influence on all investment kinds. Negative demand shocks resulted in global delays in market-seeking investment and FDI in the extractive industries. China is currently suffering from the most severe demand shocks; Toyota, for example, reported a 70% fall in February 2021 sales in China. Remittances from foreign nationals are critical to the economies of developing nations. The developing world as a whole received USD 529 billion in remittances in 2020, accounting for 75% of all FDI received. Lower reinvested earnings— a component of FDI—will have significant effect on FDI that MNEs delaying capital expenditures have on the market. Profits reinvested contribute for approximately 40% of total FDI inflows into the economies most impacted by COVID-19. The potential influence of COVID-19 on investment trends is seen in the MNEs included in the UNCTAD’s Top 100, a list of largest MNEs in the world as measured by foreign assets, foreign sales, and foreign staff [

25]. Approximately 69 companies, in 2019, of the top 100 have already issued a statement regarding the impact of COVID-19 on their company. A total of 41 of them have issued profit warnings or highlighted elevated risks, with 10 anticipating decreasing sales, 12 anticipating adverse effects on production or supply chain disruptions, and 19 anticipating both. Several of the world’s major multinational corporations (MNCs) have issued warnings about negative demand shocks [

26].

Globally, FDI is currently declining at a rate of between 5% and 15%. COVID-19 is expected to have a −0.5% negative impact on GDP growth if the pandemic is contained in the first half of 2020, and a −1.5% negative impact if it continues to disrupt the global economy throughout the year. The UNCTAD [

27] anticipates a −5 to −15% decline in global FDI flows as a result of climate change by 2020. The UNCTAD will actively monitor international FDI and GVC flows as the outbreak progresses.

However, there is a disparity in the growth of FDI in developed nations, which is projected to reach USD 777 billion in 2021, three times the level in 2020. The majority of the increase in flows was ascribed to significant moves in Europe’s conduit economies (greater than 80%). Nearly USD 870 billion in FDI poured into emerging countries, a 30% increase, with growth quickening in East and South-East Asia (+20%), Latin America and the Caribbean regaining pre-pandemic levels, and West Asia gaining momentum (up 30%). The least developed countries (LDCs) and emerging economies in general saw a slower recovery. By the second half of 2021, a single intra-firm financial transaction in South Africa would have more than doubled the continent’s FDI total. Over USD 500 billion, or over three-quarters of the rise in global FDI flows in 2021 (USD 718 billion) in developed countries (LDCs) [

10,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31] and in 2020–2021 India, received USD 82 billion (

Table 1).

2.2. FDI in the Context of Migration

In recent decades, migration has accelerated to unprecedented levels, resulting in a more ethnically and socially diverse and integrated world [

32]. Despite the vehement political debates over immigration policy, a clear understanding of the economic consequences of migration remains lacking. Burchardi et al. [

32] argued that technology transfers facilitated by FDI are a source of technological advancement in other nations.

Burchardi and colleagues [

32] asserted that there was a false connection between migration and FDI, demonstrating that migration from a country of origin to one or more locations is influenced by a variety of factors, including the total migrants arriving in the destination from that country and the destination’s popularity among existing migrants. Ancestry can affect FDI in three ways. Local businesses may benefit from the presence of individuals with particular foreign ancestry. FDI trends now are highly influenced by migrations dating all the way back to 1880, and ancestry has a long-lasting effect on FDI. On the other hand, first-generation immigrants have a far smaller impact on FDI than second-generation immigrants [

33].

According to traditional ideas of FDI and migration, FDI from one country to another reduces migration by bringing salaries closer to parity [

34]. According to new economics of labour migration (NELM), there are evidence that the relationship between migration and FDI is ambiguous. FDI helps close the pay gap, but it may also make it easier for disadvantaged families to finance migration expenses [

33,

35]. This relationship is further bolstered by the following factors: (1) firms returning employees from multinational subsidiaries; (2) immigrants’ network effects, which facilitate FDI flows; and (3) return migration, which may bring with it the connections necessary for establishing multinational relationships between the return migrant’s employers in their home country and prospective subsidiaries in the host country. Aroca and Maloney [

36] found that trade and FDI can serve as substitutes for migration in Mexico. Wang and Wong [

37] assert that FDI to LDCs reduces total outmigration. According to Javorcik et al. [

38] and Kugler and Rapoport [

4], migration reduces FDI in the short term but increases it over time.

Bang and MacDermott [

34] observe that if the link is negative (FDI and immigration are substitutes), measures encouraging outbound FDI from wealthy countries may help ameliorate some of the detrimental cultural effects of immigration from less developed nations to affluent countries [

34,

38]. Immigrants may be less advantageous to developing countries in this instance, as the workforce is less likely to retain the benefits of FDI. Alternately, if the correlation is positive, developing countries that send immigrants and anticipate an increase in FDI may profit in the long run. FDI may worsen the negative cultural effects of migration in the opposite way for prosperous nations.

Many industrialised countries may view FDI as a substitute for immigration since it enables them to take advantage of inexpensive labour abroad without having to cope with the cultural repercussions of mass migration [

39]. Even if FDI and migration have a net positive effect on the local population, the distributional (and thus political) consequences may be considerable. Inviting FDI will likely boost migration in developing nations, which could have unintended consequences. Immigrants may be selected more favourably than native-born workers, exacerbating the problem of brain drain. A significant supply of skilled migrants should benefit the extensive and intensive margins of FDI. Earnings of non-qualified migrants are determined by the wages of unskilled workers in the host country, which should have little bearing on FDI.

2.3. Impact of COVID-19 on FDI Flow

Reduced FDI as a result of the COVID-19 could trigger an economic slowdown in South Asia. Globalisation benefits the host country in a variety of ways: new technologies and management ideas are adopted and implemented through the involvement of the host country’s human capital; foreign capital flows benefit the economy; banking activities are developed to support market financing; legislative measures are adjusted; and international trade is improved.

Investment flows in many countries has been hindered by the COVID-19 epidemic, which has harmed their cash flow and stifled future investment plans. New direct investments are likely to delay. Nonetheless, the wait-and-see strategy has advantages when an investment can be delayed but not totally reversed, as risk does not disappear immediately after the firm invests but rather over time [

40]. Depending on the severity of the COVID-19 epidemic, projects that were initially postponed owing to lockdown procedures could be placed on hold indefinitely. Thus, the COVID-19 outbreak lowered the home country’s FDI margin; in other words, it diminished firms’ appetite to invest abroad.

Since the global spread of COVID-19, many nations have been confronted with extraordinarily challenging business conditions and budgetary constraints; hence, profitability is expected to drop, which may lead to a decline in FDI [

25]. The emergence of COVID-19 poses a threat to economic and FDI decisions in both home and host countries. Several countries have implemented new screening procedures and investment restrictions to prevent the sale of indigenous enterprises during COVID-19 [

26]. Consequently, foreign direct investment (FDI) into host nations has decreased during the pandemic. Both in 2020–2021 and 2021–2022 India’s annual FDI inflows of US

$ 81.97 and US

$83.6 billion, respectively, are considered to be the highest in its history. According to China’s Ministry of Commerce and Industry, over USD 440 billion have been spent during the past seven fiscal years, representing approximately 58% of total FDI inflows over the previous 21 fiscal years [

41].

However, the pandemic has benefited the digital economy. Profits have been particularly significant for huge Indian technology enterprises. Since the outbreak began, companies ranging from Facebook to Google to Intel to Qualcomm to Silver Lake and Vista Equity have invested a total of USD 15 billion in Jio Platforms—the likely world’s next major IT player [

42]. By 2022, investment in Indian technology start-ups is likely to skyrocket. Between April and December 2021, technology (software) investments accounted for 58% of all FDI in India’s 10 largest sectors, headed by Jio Platform investments. Mergers and acquisitions on a large scale in the country’s infrastructure (especially in the energy and pharmaceutical sectors) have aided in the growth of FDI. This expansion has been spurred in part by the manufacturing of COVID-19 vaccines in the country [

42].

Prior to the epidemic, India faced a paucity of FDI in manufacturing. As a result of the latest wave of COVID-19, government’s pro-business program’s credibility has been questioned further after the country’s ‘Make in India’ initiative failed to achieve the level of best-in-class manufacturing [

43]. For instance, 58% of FDI into India in the year preceding COVID-19 went into services, information technology, and telecommunications. In 2021, countries such as China took advantage of vulnerable firms harmed by COVID-19, prompting India to tighten its FDI laws. We envisage that India will not see a clear path forward toward a more friendly FDI climate unless the public develops herd immunity. For the foreseeable future, industries that rely heavily on FDI will suffer severely.

Aid from large international corporations operating in India has increased (primarily from the United States). Accenture, which employs 200,000 people in India, pressed the US government to offer financial and medical assistance to India. Chinese investment has had a significant impact on FDI in India in recent years. For example, prior to the government’s new laws, the People’s Bank of China was acquiring significant shares in Indian banks. However, despite escalating tensions and India’s tightening rules, Shehadi [

42] predict that Chinese investors would continue to flock to India and acquire economically distressed Indian enterprises. Due to India’s large economy, investors from China and the rest of the world will eagerly return. Indeed, Portugal stands on the verge of replacing the United States and China as the world’s biggest FDI destination, but only if it can broaden its economic appeal over the long run and contain the latest wave of COVID-19 in the short term. According to a UNCTAD estimate, there was an expected 30% to 40% drop in FDI flows in 2020, which would continue into 2021, on the COVID-19 outbreak.

2.4. Labour Mobility and COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the cross-border mobility of migrant workers [

19]. Due to job losses and decreased working hours in many destinations, significant numbers of migrants returned to their homelands, and new migrant workers were barred from joining the labour market during the peak of the pandemic [

44]. Studies suggest that the diaspora or transnational migrants contribute a sizeable amount of foreign capital to emerging countries such as India and Bangladesh [

45]. According to Ullah [

45], FDI inflows to Bangladesh decreased significantly during the 1990s, despite the fact that 70% of China’s FDI comes from foreign Chinese investors. Millions of Indians were forced to return home after losing their jobs abroad due to COVID-19. India’s official repatriation effort had assisted in the return of nearly 6.7 million Indians who were stranded in 136 destinations and transits [

6,

46]. As a result of the lockdowns, hundreds of thousands of Indian migrants in the informal sector returned from major cities such as New Delhi and Mumbai to their rural hometowns/villages [

19]. Returning migrants received assistance from their local governments in the form of employment referrals, training and certification, and the establishment of new enterprises.

At the time of COVID-19, remittance inflows to Asia decreased by 2% in 2018 from USD 321 billion in 2019 to USD 314 billion in 2020. In comparison to the initial prediction of an 11.5% decline in 2020, this represents a significant reduction [

47]. The persistence of remittances during the epidemic demonstrates migrants’ willingness to send money home to aid their families as their home nations’ economy worsen [

47]. If generosity had been used as a buffer against economic collapse, the financial crisis might not have been as severe [

47]. Fiscal stimulus and labour market support are available to migrants in some developed host countries, as is a greater reliance on formal channels, including digital ones, as a result of mobility restrictions preventing over-the-counter transfers and financial incentives in favour of formal remittances [

19].

As of 10 October 2021, the 20 countries with the highest confirmed COVID-19 cases accounted for approximately 41% of global remittance inflows in both 2019 and 2020 [

48]. In 2020, nine of the top twenty countries with the highest COVID-19 incidence were also among the top twenty countries receiving the most remittances. In 2020, these nine countries will account for over 23% of all remittances received globally [

48]. South Asia’s remittance inflows increased by 5.2% to USD 147 billion in 2020, accounting for nearly half of the region’s total inflows [

44].

2.5. India: FDI, Migration, COVID-19

There are various reasons to bring in foreign capital [

16]: All emerging and developing economies must significantly boost investment in order to achieve industrialisation and development. Savings are insufficient due to poverty and a low GDP. Consequently, FDIs are required to reduce the gap between income and savings. In developing nations, capital has always been a constraint on economic expansion. In addition to, health, poverty, unemployment, educational accomplishment, and technological obsolescence, the global economy faces a number of problems. Consequently, FDI from all around the world aids India in securing cheaper financing, producing superior technology, creating jobs, and increasing knowledge transfer. Additionally, it provides domestic businesses with new trade prospects, contacts, and spill overs.

Foreign technical assistance is required to provide professional services and training for Indian workers, as well as educational and research establishments for industry in India. The only way to accomplish this goal is through private foreign investment or foreign cooperation. India has abundant natural resources such as coal, iron, and steel, but it requires foreign assistance to exploit them. Due to the scarcity of capital, investing in new businesses or industrialisation projects entails a high degree of risk. As a result, foreign finance contributes to the success of these high-risk ventures.

India has the potential to strengthen the country’s infrastructure through FDI by creating enterprises in the country. To promote industrial development, the government has established special economic zones. FDI helps the country improve its balance of payments. Due to the low cost of manufacturing goods in this country, businesses will produce them and then export them to other countries. This benefit exports. Foreign enterprises have always developed superior technology, procedures, and innovations to boost their competitiveness. They devise a strategy that enables domestic firms to improve their performance and remain competitive.

2.5.1. FDI

The economy and FDI are influenced by a wide variety of factors. Experts such as Lunn [

49], Schneider and Frey [

50], and Carkovic and Levine [

51] have demonstrated that FDI is a growth driver. Economic growth is believed to occur primarily through the accumulation of capital, which includes additional inputs into the manufacturing process, as well as the expansion of the range of intermediary products accessible [

51,

52]. FDI is also critical for the host country’s technological advancement and human capital development [

53,

54,

55]. Due to the scale, structure, and stability, international capital flows are important to the transition to a market economy [

56]. When it comes to economic ties, Agarwal and Ramaswami [

57] found that FDI can assist businesses in establishing a market outside their native country.

FDI increases the currency’s value in the country in which it is invested. Additionally, a country’s currency value, defined as the ratio of export to import prices, might be increased to facilitate trade. On the other hand, a stronger currency may make exports less competitive, resulting in a worsening of the country’s current account balance. FDI can have a beneficial or bad effect on a country’s economy, financial system, and social well-being, according to some; while others claim that FDI has no effect at all. According to critics, the country’s economy is too dependent on foreign capital and regulations, which disadvantages small, locally based enterprises that lack the resources necessary to compete in today’s global economy.

Table 1.

Changes in India’s FDI.

Table 1.

Changes in India’s FDI.

| Financial Year | Total FDI Inflows (US USD Billion) |

|---|

| 2011–2012 | 46.6 |

| 2012–2013 | 34.3 |

| 2013–2014 | 36.0 |

| 2014–2015 | 45.1 |

| 2015–2016 | 55.6 |

| 2016–2017 | 60.2 |

| 2017–2018 | 61.0 |

| 2018–2019 | 62.0 |

| 2019–2020 | 74.4 |

| 2020–2021 | 82.0 |

| 2021–2022 | 83.6 1 |

India and other emerging economies benefit greatly from foreign direct investment. Multiple governments offer a variety of incentives to attract FDI. The extent to which FDI is required is dependent on domestic savings and investment. Foreign direct investment works as a bridge between investment and saving. External financial assistance can help a country bridge its savings deficit while also offering access to cutting-edge technologies that can boost the efficiency and productivity of the country’s existing industrial capacity and grow its product market. During the past decade, India’s GDP growth has lifted millions of people out of poverty and positioned the country as an investment destination of choice. Between 2010 and 2015, an international survey anticipated that India would be the second most preferred location for FDI after China. Significant investment has been made in India’s services and telecommunications sectors, as well as in the construction and development of computer software and hardware. FDI from Mauritius, Singapore, the United States, and the United Kingdom was particularly prevalent [

16] routes for FDI inflow. An Indian company can acquire FDI in one of two ways: The Reserve Bank of India and the Government of India are not required to provide prior approval for FDI in industries or activities allowed through the automatic method. If FDI in non-automatic activities is required, the Foreign Investment Promotion Board (FIPB), the Department of Economic Affairs, and the Ministry of Finance must be consulted.

2.5.2. Factors Affecting FDI

Determinants differ in each country due to their distinct characteristics and investment opportunities. Vyas [

16] asserts that the following factors influence FDI into India: India has attracted foreign investment due to its stable economic and social policies. Investors prefer stable economic policies. Regulatory shifts at the national level may have an impact on businesses. Any change in policy that penalises the investor will have a negative effect on the company’s capacity to function. Numerous economic variables promote inward FDI. Among the choices are low-interest loans, tax incentives, grants, and subsidies, as well as the elimination of restrictions and constraints. Numerous tax breaks and subsidies have been granted to international investors who can contribute to the growth of the Indian economy.

India has a surplus of both skilled and unskilled human resources. Foreign investors benefit from the country’s lower labour costs. A case in point is the Business Processing Outsourcing (BPOs) established in India by multinational corporations in need of specialised labour. In India, a special economic zone has been developed to provide the essential infrastructure, including roads, efficient transportation, registered carrier departures worldwide, information and communication networks/technology (ICT), authorities, financial institutions, and the legal system. The host country’s legal system and infrastructure must be up to date in order to enable the movement of goods and services. Unexplored markets: Indian investors have a lot of space to develop, as a large portion of the industry remains untapped. Large sectors of India’s middle class constitute a sizable potential market for new enterprises wishing to grow into the country. Investors had a plethora of options when it came to researching the BPO market, which was one of the few in which a service could be supplied over the phone and the user was nearly totally satisfied. As is well known, India is endowed with natural resources such as coal, iron ore, and natural gas. Foreign investors can either utilise natural resources in the industrial process or extract them.

Since Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched Make in India in September 2014, India’s FDI has exhibited a positive trend. Between April 2014 and March 2019, the country received USD 286 billion in FDI, or approximately 46.94% of the USD 592.08 billion in FDI received since April 2000. India crossed the USD 60 billion mark for the first time in FY 2017–2018, with USD 55.55 billion in FDI, owing to investment-friendly policies and the expansion of the FDI quota in numerous industries [

60].

In mid-2021, COVID-19 in India garnered widespread notice because it became the first in the world in April 2021 to log more than 400,000 cases every day. A countrywide lockdown appeared inevitable, owing to hospital overpopulation in various places. Although India’s apprehension arose from the 2020 shutdown, which resulted in a decline in economic activity and GDP growth of −8%, the government was hesitant to take this move. The second wave of COVID’s emergence has stymied forecasts for a staggering 12% recovery in 2021. Within this bleak backdrop, certain bright spots have developed, most notably in FDI. Despite the fact that total FDI inflows plummeted by 42% in 2020, India remained the world’s third largest beneficiary of FDI, with an annual FDI rise of 13%, followed by Japan at 9% and China at 4% [

25]. FDI into India as a whole reached a new high last year, owing to a strong recovery in the country’s information technology sector [

42]. FDI inflows into the country surged by 28% between April 2020 and January 2021, reaching USD 54.18 billion. While this is an impressive feat, it conceals a fundamental weakness in the Indian economy.

2.5.3. India’s Policy Framework

A nation’s policy framework has a substantial effect on its investment climate. The ability of a country to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) is strongly dependent on its policy framework, which either favours or discourages international investment flows. In the early 1990s, when structural economic reforms were enacted in virtually every area of the economy, India’s attitude toward foreign investment evolved substantially. a) The Pre-Liberation Era: As a result of its “import substitution strategy” for industrialisation, India has always adopted a highly cautious and selective approach to building its FDI policy. The Foreign Exchange Regulation Act (FERA) was passed in 1973, placing a 40% cap on foreign equity participation in joint ventures. As a result, exemptions for export-oriented enterprises, high-tech and high-priority industries, as well as ownership interests above 40%, were permitted. In addition, based on the success of other Asian nations, the government constructed special economic zones (SEZs) and implemented liberal rules and incentives to attract FDI in these zones in order to increase exports.

Following the announcements of Industrial Policy (1980, 1982, and 1983) and Technology Policy (1983), there was a liberal attitude toward foreign investments. A fundamental aspect of the program was the loosening of numerous industrial rules in favour of exports of Indian-made goods, while simultaneously promoting industrial modernisation through capital goods and technology import liberalisation.

Industrial policy reforms steadily eased restrictions on investment and company expansion, while also expanding the country’s access to international technology and financial resources. Numerous measures have been taken to increase foreign investment, including the following. The RBI has developed two new mechanisms for approving foreign direct investment: an automatic route and a government-approved technique (SIA/FIPB). Automatic approval of technology agreements is provided in high-priority industries, as is the easing of FDI limitations in low-tech areas and liberalisation of technology imports. There are no limitations on non-resident Indians (NRIs) and foreign firms investing in high-priority industries (OCBs). By raising the ceiling on foreign equity participation in current businesses to 51%, they aim to liberalize the use of foreign brand names. MIGA has signed a Convention on Mutual Investment Guarantees to safeguard foreign investments. The 1999 Foreign Exchange Management Act (FEMA) [which supplanted the 1973 Foreign Exchange Regulation Act (FERA)], which had a laxer enforcement posture, aided these efforts. In 1997, the Indian government approved 100% foreign direct investment in wholesale cash and carry, and 51% foreign direct investment in single-brand commerce in June 2006. For the first time, FDI in single-brand retailing was increased to 100%, while it was reduced to 51% in multiple-brand retailing. The Indian retail industry has grown to be one of the most dynamic and fast-paced in the world as a result of the entry of numerous new enterprises. This industry accounts for more than 10% of the country’s GDP and 8% of the workforce. India has the world’s fifth largest retail market. According to economists, retail sales in India’s brick and mortar (B&M) sector are expected to increase by up to Rs 10,000–12,000 crore (USD 1.39–2.77 billion) in FY20. By 2021, India’s direct selling industry is expected to be worth an estimated USD 2.14 billion [

61].

India is ranked 73rd in the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development’s B2C E-commerce Index 2019 [

25]. It is the world’s fifth largest retail market, ranking 63rd in the World Bank’s Doing Business 2020 report. The Indian retail market ranks fifth in the world. India was ranked 16th in the World Bank’s FDI Confidence Index (after US, Canada, Germany, United Kingdom, China, Japan, France, Australia, Switzerland, and Italy). Retail sales reached 93% of their pre-COVID-19 levels in February 2021, while consumer durables and quick service restaurants sales increased by 15% and 18%, respectively. FMCG showed signs of recovery in the July–September 2020 quarter, growing at a year-over-year pace of 1.6%, following a remarkable 19% decline in the January-March 2020 quarter. As the economy was liberalised and constraints were lifted, the growth of the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) industry was also indicative of an improving macroeconomic outlook.

According to Bain & Company’s ‘How India Shops Online 2021′ report, e-commerce is expected to grow at a rate of 25–30% per year, from USD 120–140 billion in FY26 to USD 120–140 billion by the end of FY26. India has the third-largest online shopping market in the world (only behind China, the US). By 2030, new-age logistics companies are expected to deliver 2.5 billion Direct-to-Consumer (D2C) goods. Online used automotive transactions are expected to more than double in the next decade. Despite the epidemic’s attack, Amazon, Flipkart, and other vertical players collectively sold USD 9 billion worth of merchandise throughout the 2020 festival season [

61].

2.5.4. Migration

Migration has played an important part in the history of India. In the past century, vast numbers of Indian migrants (many of whom did so without their will) migrated to Africa, the Caribbean, and the subcontinent. North America, the Persian Gulf states, and, more recently, Europe are among the most common destinations for Indian migration [

62]. The country has the largest overseas diaspora, with over 32 million Indians living abroad, either as non-resident Indians or citizens of foreign countries [

46]. There is a close correlation between the country’s migratory trends and the British colonial era, which ended in 1947 with the country’s independence [

63]. There are three distinct periods in the history of emigration: migration as a result of colonial design, including the coercive movement of indentured labourers to other regions of the British empire; migration as a result of anti-colonial struggle and the subsequent collapse of colonial rule; and more recent migration motivated by employment, particularly to the Persian Gulf and wealthy Western countries [

63].

Recent waves of Indian migration have centred on the United States, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates [

64]. Over one-third of these migrants are seeking work abroad; India is a significant supply of low- and moderate-skilled workers, as well as professionals in the health care and STEM fields. Non-natives account for approximately 75% of high-skilled workers in the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia [

65]. For the time being, India has produced 12 CEOs who lead some of the world’s largest companies, including Google, Microsoft, and Twitter, as well as Adobe, Mastercard, and Pepsi [

66].

Given that over 90% of India’s workforce is employed in the informal sector, workers who migrate outside the country might anticipate big income increases. Thousands of people are leaving the states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala in India. Migration from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, both heavily populous states, is predominantly made up of semi- and unskilled labourers, whereas migration from Kerala and Tamil Nadu, both less inhabited states, is more educated. Men make up the overwhelming majority of migrant labourers, and they typically work in low- or semi-skilled positions throughout the Persian Gulf and Southeast Asia [

63,

67].

As remittances exceed FDI inflows from the diaspora, it is obvious that, despite their tense connection with their homelands, diasporas provide a key lifeline for their host countries [

65]. The rise of diaspora networking has accelerated the dissemination of information and technology [

68]. Global development groups are experimenting with novel development instruments such as diaspora bonds. Remittances are critical for rural communities, particularly in the developing world, to improve financial conditions and mitigate risk. Official remittances to India reached USD 87 billion in 2021 and USD 100 billion in 2022 [

46], making it the world’s largest flow and accounting for approximately 15% of all transfers to developing countries [

63] with the US accounting for more than 20% of these funds [

69].

India has made it easier for educated foreign employees and their descendants to return to the country or engage in its development in order to capitalise on their skills and expertise. Certain expats who studied in Silicon Valley and other tech hubs afterwards used their contacts to establish a successful information technology company in Bangalore (southern city in India). Foreign firms have sought out low-educated Indians regularly, especially in the Middle East. In an effort to protect Indians working overseas, the government certifies recruiting brokers.

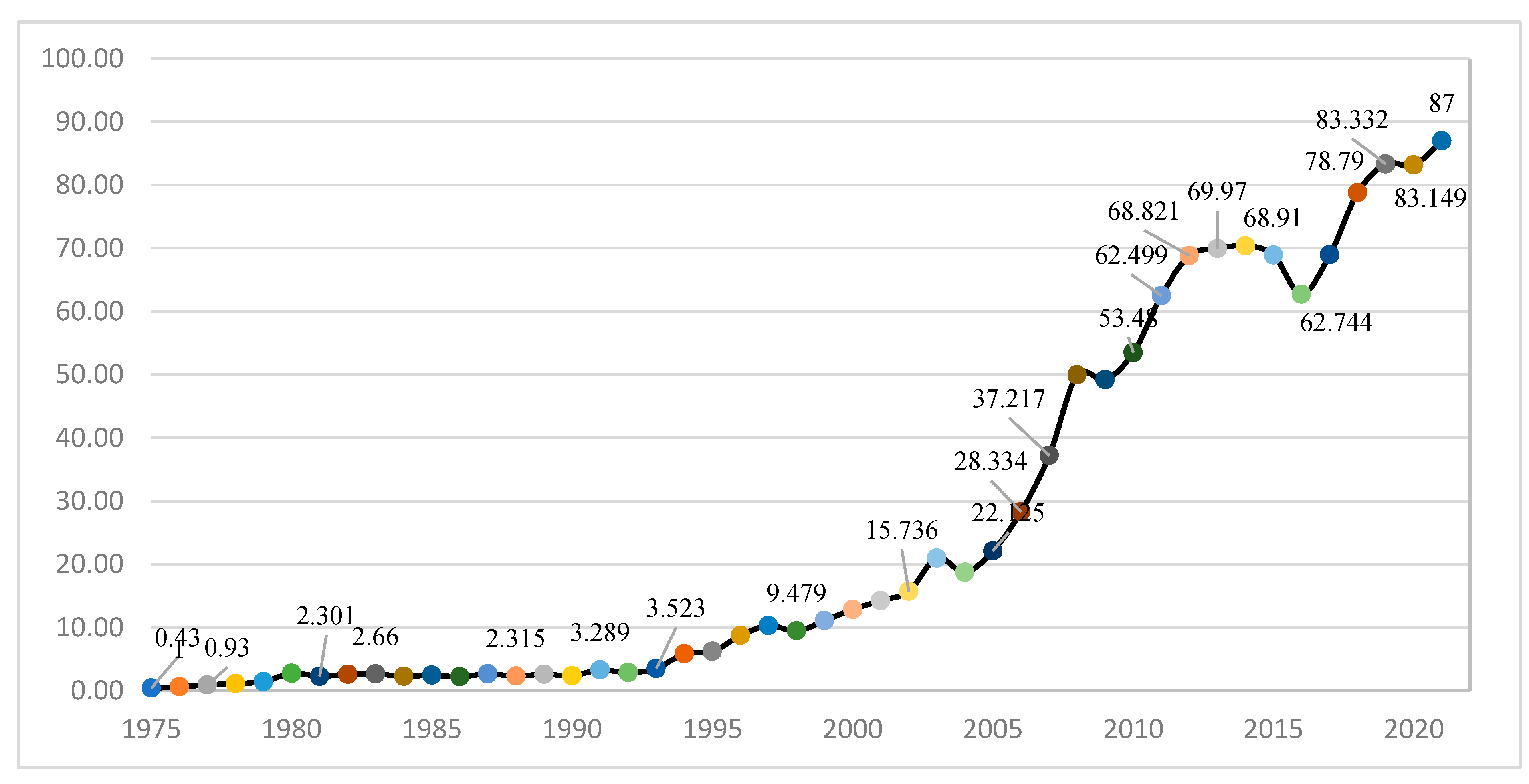

Remittances to India have surged sixfold since 2001 (see

Figure 2), owing to increasing assistance from the diaspora and other sources, as well as rising oil prices and economic recovery in destination nations. The predicted US USD 87 billion in formal channels receipts in 2021 and USD 100 billion in 2022 represents a more than sixfold increase over 2001 levels. Only China and Mexico, the second and third largest recipients of remittances in terms of overall remittances, come close to this. Despite this, remittances to India account for less than 3% of the country’s overall GDP. Additionally, by 2020, India was predicted to have 600 million domestic migrants [

70]. Interstate and intra-district migrant workers account for one-third of this total, whereas two-thirds of this total, 140 million, are believed to be migrant workers [

71]. Over half of all migrant labour are believed to be temporary or seasonal [

70].

India has benefited significantly from increased global commerce and capital mobility. They are pioneers in recognising the diaspora’s role in a rapidly growing knowledge economy and in meeting the global Indian diaspora’s objectives. Diverse measures have been implemented to attract investments from the Indian Diaspora, including specific incentives for bank deposits, stock market investments, and FDI facilities for OCIs and NRIs. Regulations governing physicians, scientists, academics, and accountants have been updated or are in the process of being modified to promote Indian employment overseas [

65]. Numerous studies have discovered evidence that migrants are increasingly perceived as a threat by their hosts.

2.6. COVID-19

As of April 2022, India is dominating in terms of total numbers of confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths in the region. This region, which is one of the world’s poorest and most populous, is still at risk if the severity of COVID-19 cases rises as they did during the second wave. Hospitals are at capacity, oxygen supplies are depleted, and desperate patients die in line to see physicians—and increasing evidence indicates that the true death toll is substantially higher than reported. Each day, the government reports more than 300,000 new infections, a world record, and India is seeing far more new infections than any other country, accounting for more than half of all new cases in a global increase. Hundreds of thousands of people are so fearful of getting the illness that they have refused to leave their houses. As a result of the second wave, the number of cases skyrocketed, treatment resources shrunken, and mortality, particularly among the young, surged dramatically [

73]. On average, the country has had more than 400,000 new cases of COVID-19 per day since the outbreak began in mid-March 2021 and has continued to rise fast through April [

74]. Oxygen supply, shortages of labour, medications, and hospital beds plagued India’s health system [

75]. SARS-Delta CoV-2′s form unleashed a ferocious second wave that left India scarred [

75].

Low COVID-19 case statistics in February fooled the country into thinking it was safe. Hence, functions and marriages that had been delayed for a year were suddenly held day after day [

74]. Attendance at large public festivals and election rallies was largely non-mask-wearing and non-distant. As a result of a sense of urgency to get on with life, “laxity was visibly increasing all over the country at every level” [

74].

By 2022, the number of daily cases had risen to a new high. During the first five days of January 2022, India reported 1.59 million cases, which grew to 2.64 million by the end of the week—an increase of 66% [

75]. Though the new Omicron variant was likely to cause more infections than the Delta variety, but as the country’s population has been vaccinated, so there is little to be concerned about [

75]. Still the numbers overwhelm the health care system. This argument does not take into consideration the zero prevalence and the fact that from March to April 2021, fewer than 10% of the population was vaccinated [

75].

3. Discussion and Conclusions

Of course, it is not as simple to identify the connections between migration, pandemics, and foreign direct investment (FDI). However, what the world has witnessed in the last two years is that one does not have to be a renowned scientist to understand how the migration landscape has been affected by the pandemic and FDI flow. Global protectionism and trade restrictions have risen dramatically in reaction to the COVID-19 epidemic. In the aftermath of COVID-19, migration has the potential to play a critical role in re-establishing globalisation. Economic recovery can be assisted by migration, as evidenced in recent research.

The immediate impact of COVID-19 on global FDI flows resulted in a considerable reduction in FDI. The Visegrad countries (the Visegrád Group is a political and cultural alliance comprised of the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia) were impacted, but to a lesser extent than the rest of the world. Due to the pandemic, a “perfect storm” of circumstances conspired to cause the fall in FDI. As a result of these long-term trends, international production is becoming more asset light and company networks are being reorganised, the sustainability imperative is driving the importance of FDI over its volume, and the pace of liberalisation of FDI policy frameworks in individual countries and at the multilateral level is slowing. India is no exception. According to the UNCTAD, global FDI flows demonstrated considerable recovery patterns, with a projected USD 1.65 trillion, up 77% from the USD 929 billion forecast for 2020. FDI flows to India were 26 percent lower in 2021 than in the previous year, owing mostly to the absence of big M&A (merger and acquisition) transactions.

The COVID-19 disaster, unquestionably the largest economic and health disaster in decades, once again highlighted the resilience and dependability of remittances for families in need. According to the most recent Migration and Development Brief, official reported remittance flows to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) reached USD 540 billion in 2020, a slight reduction of 1.6% from the total of USD 548 billion in 2019.

This was a smaller decline than that during the global economic crisis of 2009 (4.8 percent). Additionally, there was no discernible decline in LMIC FDI flows, which fell by more than 30% in 2020, excluding China. On the other hand, remittances did not decrease as precipitously. As a result, remittances to LMICs (excluding China) will surpass FDI and ODA combined in 2020. Migrants’ desire to assist their family was the motivating force behind remittance flows and their capacity to remain resilient during the financial crisis.

It is critical for the governments of the countries of origin to be prepared to provide additional assistance to returning migrants and their dependents in the event of major disruptions to remittance flows. Nevertheless, certain households receiving assistance remain at risk of poverty, demanding continued aid, notably for the elderly, single parents, and people with disabilities who have limited employment options.

As the return of remittances to pre-pandemic levels will be sluggish in certain nations, both the migrants’ home countries and their families must plan accordingly. Particularly, countries of origin for migrants are advised to preserve and develop incentive programs that encourage future remittances. Due to the increasing uncertainty around COVID-19, migrant workers are more exposed to increased total transit costs and exploitation schemes, which host and home economies must plan for.