Abstract

The aim of this study is to assess the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on undergraduate students’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors on hand and mobile phone hygiene. An anonymous self-reported questionnaire was distributed among 100 Greek male and female undergraduate students of all academic years who attended healthcare as well as non-healthcare curriculums. Descriptive statistics and statistical tests (chi-squared and Wilcoxon signed-rank test) were used (α = 5%). Students provided better responses during COVID-19, compared to the period before the COVID-19 pandemic, concerning their hand washing frequency (p < 0.001), hand washing circumstances, certain hand washing procedures, as well as their mobile phones’ cleaning/disinfection methods and frequency (p < 0.001). Statistically significant differences were observed between males and females in their knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors on hand and mobile phone hygiene, followed by faculty and year of studies. Overall, being a final-year female undergraduate student of health sciences has a positive influence on correct knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors on hand and mobile phone hygiene.

1. Introduction

Mobile phones are considered an essential “high-touch” handheld item in today’s society [1]. They are part of the so-called “emotional technology” and an integral accessory for both professional and private life. Users have an emotional relationship with their mobile phones and feel connected to them as a consequence of the personalized services provided through them [2]. As society moves towards the use of this advanced technology, many people do not consciously realize how often they touch their phones or where they use them [1].

The use of mobile phones in multiple places has been found to increase the risk of cross-contamination, especially in cases where no special care for phone cleaning and disinfection is taken. Mobile phones act as a reservoir of microorganisms, as well as a vector of infections [3]. Microorganisms that are present on the surface of a mobile phone can be transferred to the user’s skin or to other surfaces and food, where they can survive and multiply [4]. Further, the heat generated during their operation, as well as their placement in a pocket, creates the right conditions for the incubation of pathogenic microorganisms [1].

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, mobile phone manufacturers stated that the use of 50% alcohol damages the mobile phone screen. Many microorganisms, including SARS-CoV-2, cannot be eliminated by alcohol concentrations below 55%. In fact, two of the biggest mobile phone companies (Apple and Samsung) did not recommend the use of any chemical substances or sprays for cleaning the mobile phone screen. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, both Apple and Samsung have revised their user support guidelines, stating that 70% isopropyl alcohol, or disinfectant wipes, can be used to wipe the exterior of mobile phones when powered off [5].

Even the complacency that the use of protective accessories on mobile phones reduces their microbial load seems to be disproved. It was found that the application of plastic protective cases, films, and screen protectors, does not affect the levels of microbial load and colonization on mobile phones, as their use remains unchanged, even with these materials applied. In any case, the use of alcohol-based disinfectants can effectively reduce the number of colonies on mobile phones by 75% [6].

While mobile phone contamination in hospital settings has been thoroughly studied, there are little data on mobile phone contamination in the academic community [7]. The use of mobile phones is widespread among undergraduate students, serving social and academic purposes. Those who attend programs in health sciences use their mobile phones during their internship in hospitals or in clinical laboratories. At the same time, students of other sciences also use their mobile phones when they practice or work in offices, where a large number of people are usually present [8].

In addition, mobile phones can act as “Trojan horses” in the spread of pathogens, especially during epidemics and pandemics, but this does not mean that the importance of proper hand hygiene should be underestimated. Specifically, during the COVID-19 pandemic, hand hygiene has been recommended as a key infection control strategy by all leading health organizations [9]. Although the role of healthcare workers’ hands in the spread of nosocomial infections has also been highlighted by many previous studies, there are still only a few studies investigating the hand hygiene of undergraduate students.

It is, therefore, obvious that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the hygiene behaviors of certain social groups remain unstudied. The aim of this study is to assess the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on undergraduate students’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors on hand and mobile phone hygiene in a Greek university setting. The findings of this study are considered of great importance, as they provide a clear view of how the COVID-19 pandemic triggered the changes in students’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors on hand and mobile phone hygiene based on their sex, faculty, and year of studies, where differences are expected.

2. Materials and Methods

The self-reported questionnaire method was used for the assessment of the undergraduate students’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors on hand and mobile phone hygiene.

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted between February and May 2022. The Alexandreia campus of the International Hellenic University, located in the Sindos region of Thessaloniki, Greece, was selected as the setting to conduct the research. This campus consists of faculties of healthcare as well as non-healthcare curriculums, making it the ideal setting for the purposes of this study.

At the time of the study, emergency governmental measures to protect public health against the risk of further spread of COVID-19 had been enacted by law for the entire Greek territory, thus for all Greek Universities as well. Therefore, the use of masks was mandatory for all students, teachers, or other staff of the university, in all indoor and crowded outdoor areas of the university, while the conduct of classes was in-person with maximum room capacity. In addition, the entire academic community was required to adhere to personal hygiene measures and was advised to use alcohol-based hand sanitizers. Finally, informational posters on the use of masks and personal hygiene measures were posted in all areas of the campus, while instructional brochures for proper hand washing were posted above each toilet sink.

2.2. Study Population

A convenience sample of 100 passing male and female undergraduate students of all academic years, who attended healthcare as well as non-healthcare curriculums, participated in the study. The participation was voluntary, and the inclusion criteria were as follows: undergraduate students aged at least 18 years old; undergraduate students who attended curriculums at the Alexandreia campus of the International Hellenic University; undergraduate students who had a mobile phone device; undergraduate students who consented to participate in the study.

Therefore, the exclusion criteria were as follows: students under 18 years old; post-graduate students, doctoral students, or any other member and staff of the university’s academic community; undergraduate students who did not attend any curriculums of the campus; students who did not have a mobile phone device; students unwilling to consent for participation in the study. Given the above criteria and parameters, the sample size is considered satisfactory [8]. Finally, the study was conducted unannounced, on different days, and at random working hours of each week, while the study’s sampling point was each time placed at different and random locations and faculties of the university campus in order to collect a representative sample and to minimize the “Hawthorne effect” [10].

2.3. Questionnaire

An anonymous self-reported questionnaire was distributed to the participants, assessing their knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors on hand and mobile phone hygiene. The questionnaire consisted of 40 questions, which were separated into three main parts: Q1–Q5 for demographics (Part A); Q6–Q32 for hand hygiene (Part B); Q33–Q40 for mobile phone hygiene (Part C). For the composition of the study’s questionnaire, part of the questions from the research questionnaires of Głabska et al. on hand hygiene [11], as well as of Cicciarella Modica et al. on mobile phone hygiene [9], were used after permission was obtained by contacting the research teams’ correspondence.

The questionnaire was translated to Greek, which is the mother language of the study’s participants, applying a triple translation method (initially from English to Greek, then from Greek to English, and finally from English to Greek) in order to avoid any discrepancies and misunderstandings [12]. Before its intended use, the questionnaire was pilot tested by 10 participants matching the inclusion criteria to ensure that it was accurate and understandable [13]. The time required to complete the questionnaire was estimated to be 10 min.

Some of the questions (Q13, Q15–Q32, and Q35–Q36) were divided into two parts, asking the participants each question twice; for the period before the COVID-19 pandemic and for the period during the COVID-19 pandemic. To enable an easier recall, the period before COVID-19 was defined as the period when there was no mask use obligation and social distancing enforcement at universities, while the period during COVID-19 was defined as the current state that existed at the time of the study. Such a recall period is considered to be reliable for studies conducted on adults concerning various behaviors [11]. In this article, the results of these particular questions asked for the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods of COVID-19 are presented.

More specifically, a close-ended question concerning the hand washing frequency was asked, with the following ordinal answers available: “not at all”, “1–2 times/day”, “3–5 times/day”, “6–10 times/day”, “11–15 times/day”, “16–20 times/day”, “21–30 times/day”, and “>30 times/day”. In addition, the hand washing circumstances were also asked as close-ended questions, offering the ordinal answers: “never”, “sometimes”, and “always”. The asked circumstances of hand washing each began with “I wash my hands…” completed each time with the following phrases: “after coming back home”, “after handshaking”, “after using public transportation”, “after money exchange”, “before touching sick people”, “after touching sick people”, and “after blowing my nose” [11].

Moreover, the hand washing procedures were assessed through close-ended questions, providing the following ordinal answers: “never”, “sometimes” and “always”. The following hand-washing procedures were asked: “I roll up my sleeves to wash my hands”, “I remove my watch and bracelets to wash my hands”, “I remove rings before or when washing my hands”, “I use soap to wash my hands”, “I wash my hands with warm water”, “I soak my hands before using soap”, “I spread the soap foam over the entire surface of my hands”, “I turn off the faucet in a public place by hand”, “I turn off the faucet at home by hand”, “I dry my hands with a disposable towel”, and “I dry my hands with a cloth towel” [11].

Finally, concerning mobile phone hygiene before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, participants were asked two questions about the frequency as well as the means used for the cleaning/disinfection of their mobile phones. In particular, a close-ended question about the frequency of their mobile phones’ cleaning/disinfection was asked, with the following ordinal choices: “never”, “once a year”, “once every 6 months”, “once a month”, “once a week”, and “every day”. Those who did clean/disinfect their mobile phones were also asked what means they use, for cleaning/disinfecting their mobile phones, with the following nominal choices available: “alcohol/alcohol solution”, “disinfectant gel”, “wet wipes”, “cloth/fabric”, and “other (a blank space was provided, in order to register any other item the students used, to clean/disinfect their mobile phones)” [9].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM® Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS®) for Windows®, version 29. Descriptive analyses were performed using frequency tables and clustered bar charts. Pearson’s chi-squared test was also used to test the independence between qualitative variables. In addition, in order to assess the differences between the two data periods (before COVID-19 and during COVID-19) collected from the same sample for different ordinal variables, the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used. The statistical significance level was set at α = 0.05 (two-tailed).

2.5. Ethics Approval

The research protocol of this study received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the University of West Attica (approval protocol code: 99754/9 November 2021). In addition, permission was granted by the Rectorate of the International Hellenic University of Greece in order to conduct the research exclusively at the premises of the Alexandreia campus, located in the area of Sindos—Thessaloniki, Greece. Participation in the study was voluntary. Participants were informed about the study’s procedures, which were written in detail on the first pages of the informed consent document. Written informed consent was received from each participant. The self-reported questionnaires distributed were anonymous, and neither any personally identifiable information nor the participants’ medical history was asked. The anonymity of the participants, as well as the confidentiality of their answers, was ensured in every stage of the study, and all collected data were used for research purposes only.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Description

The demographic characteristics of the study’s sample are presented in Table 1. A sample of 100 undergraduate students (51 males and 49 females) consented to take part in this study who attended healthcare (55%) as well as non-healthcare (45%) curriculums. Most of the students were in their final (fourth or greater) year of study (35%), followed by first-year (24%), second-year (22%), and third-year (19%) students. Public transportation was used by the majority of students (69%), while the rest of the students used private vehicles (30%) and walking (1%) in order to reach the university campus. As for the attendance frequency, most of the students reached the university campus on all five working days of the week (34%), followed by those who were present every four times/week (26%), three times/week (26%), twice/week (9%), once/week (4%), or other attendance frequency (1%).

Table 1.

The demographic characteristics of the studied sample of undergraduate students.

3.2. Hand Hygiene

The daily frequency of students’ hand washing before COVID-19 as well as during the COVID-19 pandemic periods is shown in Table 2. A significant (p < 0.001) increased frequency of hand washing during COVID-19 was observed compared to the period before the COVID-19 pandemic. The majority of students (32%) stated a hand washing frequency of 6–10 times/day during COVID-19, while for the period before the COVID-19 pandemic, most students (37%) washed their hands 3–5 times/day. It is worth mentioning that concerning the period before COVID-19, some participants were not washing their hands (1%) or doing so 1–2 times/day (21%), while during the COVID-19 pandemic, these responses were reduced (0% for “not at all” and 6% for “1–2 times/day”, respectively).

Table 2.

The declared hand washing frequency of the studied sample of undergraduate students for the periods before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

All of the assessed circumstances of hand washing were found as statistically significant and are presented in Table 3. The share of participants, who always washed their hands on each of the assessed circumstances, was significantly higher during the COVID-19 period compared to the period before the COVID-19 pandemic. The highest rates of hand washing during the COVID-19 period were stated for circumstances “after coming back home” (90%) and “after touching sick people” (89%).

Table 3.

The declared hand washing circumstances of the studied sample of undergraduate students, for the periods before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, less than half of the assessed hand washing procedures, namely those “I remove my watch and bracelets to wash my hands” (p = 0.002), “I remove rings before or when washing my hands” (p = 0.011), “I turn off the faucet in a public place by hand” (p < 0.001) and “I dry my hands with a disposable towel” (p < 0.001), were statistically significant, as shown in Table 4. The rest of the procedures assessed presented similar response rates between the two studied periods; thus, no statistically significant differences were observed. In general, the highest compliance rates during the COVID-19 period were declared for only two of the assessed hand-washing procedures, namely those of “I use soap to wash my hands” (93%) and “I spread the soap foam over the entire surface of my hands” (90%).

Table 4.

The declared hand washing procedures of the studied sample of undergraduate students, for the periods before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.3. Mobile Phone Hygiene

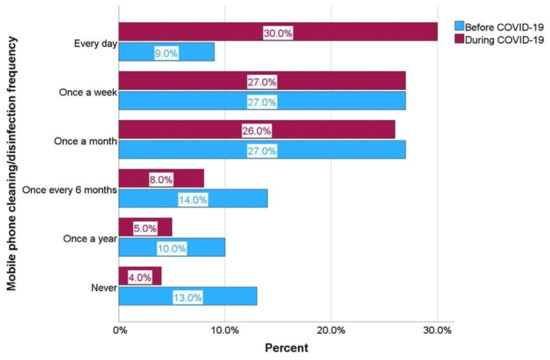

The cleaning/disinfection frequency of students’ mobile phones between the periods before and during the COVID-19 pandemic is shown in Figure 1. A significant (p < 0.001) increased frequency of mobile phone cleaning/disinfection was observed during COVID-19, compared to the period before the COVID-19 pandemic. The majority of students cleaned/disinfected their mobile phones once a week (27%) or once a month (27%) before COVID-19, while during COVID-19, most students (30%) cleaned/disinfected their mobile phones every day. It is worth mentioning that the share of students who never cleaned/disinfected their mobile phones (13%) before COVID-19 reduced significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic (4%). Moreover, students who cleaned/disinfected their mobile phones every day remarkably increased, between the two studied periods, from 9% before COVID-19 to 30% during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 1.

Mobile phones’ cleaning/disinfection frequency before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

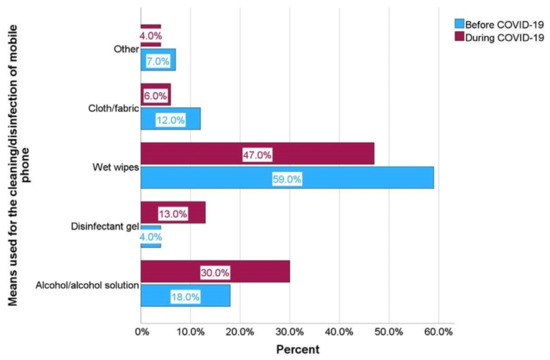

As for the means used by students for cleaning/disinfecting their mobile phones, the results are presented in Figure 2. Wet wipes were the most popular means used by the majority of undergraduate students in both studied periods (59% before COVID-19 and 47% during the COVID-19 pandemic). However, the use of cloth/fabric, wet wipes, or other means became less popular during the COVID-19 period, in which an increased use of alcohol/alcohol solution and disinfectant gel was observed.

Figure 2.

Means used for the cleaning/disinfection of mobile phones before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.4. Influence of Sex, Faculty, and Year of Studies

Statistically significant differences were observed, between males and females, in certain hand washing circumstances and procedures, as well as in frequency and means of mobile phones’ cleaning/disinfection, as presented in Table 5. Female participants provided better responses overall, in terms of knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors on hand and mobile phone hygiene, compared to male participants, on each of the studied parameters. However, while female students mostly used wet wipes to clean/disinfect their mobile phones, male students preferred the use of more effective means, such as alcohol/alcohol solution and disinfectant gel, for the same purpose.

Table 5.

Statistically significant hand washing circumstances and procedures, as well as the frequency and means of mobile phones’ cleaning/disinfection, in relation to the participants’ sex *.

Hand washing frequency during the COVID-19 period (p = 0.010), as well as hand washing before touching sick people before the COVID-19 pandemic (p = 0.013), were significantly influenced by the students’ year of studies, as shown in Table 6. Final-year students performed better in terms of hand washing frequency, followed by third-year, first-year, and second-year students. Accordingly, final-year students also provided better responses in terms of hand washing before touching sick people, followed by first-year, second-year, and third-year students.

Table 6.

Statistically significant hand washing frequency and circumstances in relation to the participants’ year of studies *.

Finally, faculty was only associated with hand washing before touching sick people, the periods before COVID-19 (p = 0.002), as well as during the COVID-19 pandemic (p = 0.003). Undergraduate students who attended healthcare curriculums offered better responses compared to those who belonged to non-healthcare curriculums, as presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Statistically significant hand washing circumstances in relation to the participants’ faculty *.

4. Discussion

This study assessed the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors on hand and mobile phone hygiene of Greek undergraduate students in a university setting, using an anonymous self-reported questionnaire. There was an equal share between male and female participants, as well as students who attended healthcare and non-healthcare curriculums from all years of study. The majority of participants reached the university’s premises, on all working days of each week, through the use of public transport. Τhis fact is a cause for concern, indicating the increased health risk faced by students due to frequent and continuous crowding and contact with various surfaces, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic period. A previous study also indicated that university students are at risk of infection due to living and working in close proximity to one another [14].

In terms of hand hygiene, an increased hand washing frequency was observed between the two studied periods. Students’ majority washed their hands more frequently during COVID-19 than in the period before the COVID-19 pandemic. Similar results were observed in previous studies, where the daily hand washing frequency of most students ranged between 6–10 times as well [15,16]. Indicatively, the nation-wide study by Głabska et al. conducted in Poland, with a sample of 2323 secondary school students aged 15–20 years old, investigated hand hygiene behaviors before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results showed that the majority’s hand washing frequency (58.4%) during the COVID-19 pandemic was significantly higher (p < 0.0001, 6–15 times/day) compared to the period before COVID-19 (3–10 times/day). In addition, those who stated that they only washed their hands whenever was considered necessary before COVID-19 (35.6%, p < 0.0001), during COVID-19, they always washed their hands after each hand-involving occasion (54.8%) [11].

Moreover, it appears that pandemic situations lead to an increased hand washing frequency. In a previous study conducted during the “swine flu” (H1N1) pandemic period in 2009, Park et al. reported an increased hand washing frequency among participants compared to one year prior [17]. In this study, however, despite the increased frequency of hand washing during the COVID-19 period, a fairly large proportion of participants caused concern due to their reduced frequency of hand washing, even during the pandemic.

Improvement in responses was also observed among participants in all of the studied hand-washing circumstances between the two studied periods. During the COVID-19 period, the proportion of participants who always wash their hands increased significantly compared to the period before the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings are in agreement with the results of a previous study by Głabska et al., where the same hand-washing circumstances were assessed, leading to similar responses, thus, significance levels [11]. Comparing the results of this study and those of the study by Głabska et al., similar response rates of “always” are observed between the two population samples during COVID-19, concerning their hand washing “after coming back home” (90% and 90.1% respectively) and “after touching sick people” (89% and 85%, respectively), as stated by the highest share of participants in both studies [11].

High response rates of hand washing after touching sick people have also been observed in previous studies [18,19]. While it is broadly known that hand hygiene must be performed before touching sick people [20], a significantly small proportion of students declared that they always wash their hands before touching sick people, compared to those who do so after touching sick people, in both of the studied periods. This finding suggests that the principles learned by students are more self-protection oriented rather than patient-protection oriented, especially in healthcare curriculums [21].

Such behaviors cause concern, as they endanger the health of patients by exposing them to various microorganisms. Bacteria, for instance, are the most dominant group of the human skin microbiome, including species of coagulase-negative staphylococci, especially Staphylococcus epidermidis, anaerobic Propionibacterium acnes, Corynebacterium, Micrococcus, Streptococcus, and Acinetobacter. The pathogenic nature of Staphylococcus epidermidis, relies on the skin condition, as well as the individual properties of the bacterial strain. Similarly, Staphylococcus aureus, which is considered a pathogenic species, may be part of the normal skin flora of approximately 10–20% of healthy people [22]. Human hands, in particular, are the main contributors to the interpersonal, intrapersonal, and environmental transfer of microorganisms [23]. In contrast, only four of the assessed hand washing procedures, namely those “I remove my watch and bracelets to wash my hands”, “I remove rings before or when washing my hands”, “I turn off the faucet in a public place by hand”, and “I dry my hands with a disposable towel”, presented a statistically significant improvement in participants’ responses between the two studied periods. In particular, it is worth mentioning that during COVID-19, fewer participants turned off the faucet in a public place by hand compared to the period before the COVID-19 pandemic, as also proved in a previous study [24]. The rest of the studied hand washing procedures had similar response rates before COVID-19, compared to the period during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, it appears that the COVID-19 pandemic had less effect on the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of undergraduate students concerning these hand-washing procedures. However, comparing the results of this study and those of the study by Głabska et al., similar response rates of “always” are observed between the two population samples during COVID-19 concerning the use of soap (93% and 94.7%, respectively), as stated by the highest share of participants in both studies [11].

As for the means used for hand hygiene, alcohol is the main active substance used in alcohol-based hand disinfectants due to its ability to denature proteins and inactivate all enveloped and most non-enveloped viruses. It is most effective at concentrations between 60% and 80% by significantly reducing the bacterial colonies on the skin, but it is incapable of eliminating most spores [25]. Furthermore, ethanol-based and isopropanol-based hand disinfectants are effective against bacteria and viruses, while soap washes away bacteria and viruses by dissolving the oily layer on the skin’s surface. In particular, SARS-CoV-2 and influenza A virus were inactivated more promptly on skin surfaces compared to other surfaces such as stainless steel, glass, and plastic. The SARS-CoV-2 survived longer on human skin than the influenza A virus, with survival times of 9.04 h and 1.82 h, respectively, which increases the risk of contact transmission, thus accelerating the COVID-19 pandemic. However, both SARS-CoV-2 and influenza A virus were completely inactivated within 15 s by applying 80% w/w ethanol on human skin [26].

Therefore, hand disinfectants are considered supplementary means for hand washing, which are more effective in removing bacteria and viruses compared to washing hands with just water. Indicatively, a significant decrease in residual fluorescence and bacterial colonies was observed after washing hands with soap under running water, after hand sanitization with an alcohol gel disinfectant, as well as after wiping hands with antibacterial wet wipes, compared to hand hygiene using only running water [27]. However, there are still ongoing debates concerning the effectiveness and preference between alcohol-based hand disinfectants and soap against pathogens [25]. Similarly, the results of this study cannot clearly demonstrate the efficacy or the participants’ preference between these two hand hygiene methods. Furthermore, there is a strong association of colonization between the hands and surfaces. As demonstrated by the findings of a study that analyzed a total of 69 pairs of samples obtained from hands and surfaces, in all cases, the same bacterial species were recovered, both from the hand and from the respective environmental surface where the sample was taken [28]. Another study compared the type of microorganisms between smartphone touchscreens and participants’ hands. It was found that only 22% of the microbiome of their hands coincided with that of their mobile phones, while for those who shared their mobile phone with others, their hands’ microbiome was only 17% similar to that of their mobile phones. Male participants shared their mobile phones more with other people by 82%, compared to females [29]. It is therefore understood that most of our mobile phones’ microbial load is of external origin.

According to the scoping review of Olsen et al., most studies identified the presence of bacteria on mobile phones, with Staphylococcus aureus, Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci, and Escherichia coli as the most dominant species, both in healthcare and community mobile phone samples. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Acinetobacter sp., and Bacillus sp. were also identified in over a third of the studies in healthcare settings. Although this review focused on the microbial identification of mobile phones in healthcare and community settings, rather than the issue of SARS-CoV-2 itself, it exposed the possible contribution of mobile phones to the transmission of microbial infections in epidemic and pandemic situations [30]. The presence of pathogenic bacteria species, such as MRSA and Escherichia coli, on hands and mobile phones is a cause for concern, especially in high-risk environments of healthcare and food-handling settings [23].

Apart from bacteria, viruses can also be transferred between a person’s contaminated skin and a fomite surface, especially in cases of high-contact surfaces such as mobile phones [31]. Respiratory viruses, in particular, have the ability to persist on surfaces for a few days, contributing to nosocomial transmission [32]. Previous studies have shown the presence of viral RNA from epidemic viruses, including metapneumovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, and rotavirus [32], as well as the presence of viral DNA from epidemic viruses, such as respiratory adenovirus and bocavirus, on the mobile phones of healthcare workers [33]. However, no viral culture was conducted in the above studies; thus, the viability of the detected viruses on mobile phones remained undetermined [34]. In contrast, the presence of infectious influenza A and B virus RNA has previously been detected on the mobile phones of patients with laboratory-confirmed influenza [35].

Regarding the SARS-CoV-2 survival on various surfaces, in the study of Riddell et al., virus isolates of SARS-CoV-2 were detected and remained infectious for up to 28 days at 20 °C, on all non-porous surfaces such as glass, polymer, stainless steel, vinyl, and paper. At 30 °C, infectious virus isolates still remained for 7 days on stainless steel, polymer, and glass surfaces, as well as for 3 days on vinyl and cotton cloth. At 40 °C, however, (a surface temperature threshold that can be reached during the operation of a mobile phone), the recovery of the SARS-CoV-2 virus was significantly lower than it was both at 20 °C and 30 °C [31]. Other studies suggested that the SARS-CoV-2 virus can remain viable on plastic surfaces for up to 7 days, while only for up to 3 h on paper [36,37]. Overall, a descending classification of the virus stability on each surface material indicates that the SARS-CoV-2 virus survives longer on polypropylene materials, followed by plastic, glass, stainless steel, pig skin, cardboard, banknote, cotton, wood, paper, tissue, and copper surfaces [36]. The persistence of SARS-CoV-2 on glass and vinyl surfaces, which happen to be the most common mobile phone materials, is a cause for concern, suggesting that mobile phones are a potential source of transmission, and should therefore be disinfected [31]. Therefore, hand hygiene alone may be less effective because cleaned hands could be recontaminated by touching contaminated personal objects or surfaces. Thus, the cleaning of mobile phones or other frequently used objects or touched surfaces should be considered [35].

In this study, most participants cleaned/disinfected their mobile phones once a week or once a month before COVID-19, while during the COVID-19 pandemic, most of them did so every day. Similar results were observed in the study by Ahmad et al., where 22.4% of participants cleaned their phones daily, 27% weekly, and 19.7% once a month [38]. However, while there is a significant increase in daily mobile phone cleaning/disinfection during COVID-19, compared to the period before the COVID-19 pandemic, a relatively large proportion of undergraduate students still performs inadequately in terms of mobile phone cleaning/disinfection frequency.

As for the cleaning/disinfection methods of students’ mobile phones, wet wipes were the most popular means used by the majority of undergraduate students before COVID-19 as well as during the COVID-19 pandemic, followed by alcohol/alcohol solution, disinfectant gel, cloth/fabric, and other means. Similarly, in the study by Ahmad et al., wet wipes were used by the majority of participants (38.6%) in order to clean their mobile phones, followed by alcohol-based disinfectant solution (16.6%), hand sanitizer (12%), and other means (2.7%) [38]. In this study, however, it is worth mentioning that during the COVID-19 period, the use of cloth/fabric, wet wipes, or other means became less popular and were partially replaced by alcohol/alcohol solution and disinfectant gel.

Moreover, in a study conducted among 304 undergraduate students, out of 151 who belonged to health sciences, 72% (n = 109/151) stated that they use their mobile phones in hospital or laboratory settings. Only 60% (n = 183/304) of all participants declared that they clean or disinfect their devices. Unfortunately, 78% (n = 142/183) of those students stated that they simply clean their devices, while 97% (n = 138/142) of them rubbed their mobile phones on their clothes, on their hands, by using a towel, or a wet cloth. The remaining 3% (n = 4/142) is a shocking example of a lack of knowledge on proper cleaning procedures since they cleaned their devices by exhaling on the surface of their mobile phones, and later rubbing them onto their clothes. Only a small percentage of 22% (n = 41/183) stated that they disinfect their mobile phones using antimicrobial substances [8].

Participants’ sex was found to greatly influence the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of undergraduate students in terms of hand and mobile phone hygiene. Female participants demonstrated a higher overall performance on certain hand washing circumstances and procedures, as well as in the frequency and means of their mobile phones’ cleaning/disinfection. There are several studies that identified sex as a determinant of hand and mobile phone hygiene among undergraduate students, indicating a better level of knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors in females than in males [13,14,15,39,40,41,42,43]. In this study, however, male participants preferred the use of more effective means, such as alcohol/alcohol solution and disinfectant gel during COVID-19, compared to females, who mostly used wet wipes in order to clean/disinfect their mobile phones. In addition, a possible explanation for females’ better response rates on the removal of bracelets, watches, and rings when hand washing is due to the widespread use of such accessories by them, compared to males.

The year of studies also influenced the participants’ attitudes and behaviors in terms of hand washing frequency during the COVID-19 period and hand washing before touching sick people before the COVID-19 pandemic. It was found that senior students washed their hands more frequently during COVID-19 compared to the students in their junior years of studies, as proved by previous studies as well [18,24]. Moreover, in this study, senior-year students also washed their hands before touching sick people, in the period before the COVID-19 pandemic, compared to the students in their junior years of studies. This behavior is observed, especially in the case of healthcare students, where first and second-year students do not come in contact with or have the responsibility of a patient, which leads to a lack of appreciation of the importance of hand washing [44].

As for the field of education, faculty was another determinant of hand washing among undergraduate students. Participants who attended curriculums of health sciences provided better responses on hand washing before touching sick people in both of the studied periods (before COVID-19, as well as during the COVID-19 pandemic) compared to students of other sciences. Healthcare students also performed better in terms of hand hygiene in previous studies, compared to non-healthcare students [16,45], especially in cases of previous and after direct contact with a patient [40]. A possible explanation of these differences in response rates is that healthcare undergraduate students come in contact with sick people/patients more frequently due to their job’s nature. However, there is evidence that students tend to overestimate their knowledge and adherence to hand hygiene practices, especially those involved in healthcare [16].

In general, young adults aged between 18 and 29 years old are considered a heterogeneous population. Thus, the identification of differences in their knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors on hand and mobile phone hygiene could be useful in terms of public health policy making and health education planning, especially in the context of greater awareness, such as the COVID-19 pandemic [45]. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study that investigates the influence of COVID-19 on hand and mobile hygiene combined, among Greek undergraduate students of healthcare and non-healthcare studies, based on their sex, faculty, and year of studies. The results of this study suggest that an increased emphasis should be given, on the education of undergraduate students, on hand and mobile phone hygiene topics, especially in junior years of non-healthcare and healthcare curriculums, as proposed by other studies as well [18,46]. Through the inclusion of the above topics in their main curriculum, the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of future healthcare and non-healthcare professionals are enhanced.

Finally, the limitations of the present study include the following: the self-reporting of information regarding hygiene habits [47], the cross-sectional design, which does not allow for causality conclusions [48], as well as the convenience sampling, used that affects the generalizability of these results [49]. Nevertheless, this study provides a clear view and additional information on the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors on hand and mobile phone hygiene. Longitudinal data are necessary to further unravel the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the above-mentioned variables. Future research should focus on investigating the transmissibility of SARS-CoV2 or other respiratory viruses among undergraduate students due to mobile phone use, as well as their isolation and viability on students’ mobile phone surfaces.

5. Conclusions

It is evident that the COVID-19 pandemic greatly affects the hand and mobile phone hygiene knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of Greek undergraduate students. Statistically significant differences were observed, concerning students’ hand washing frequency and hand washing circumstances, between the two studied periods. In general, students demonstrated an increased adherence to hand and mobile phone hygiene practices during COVID-19, compared to the period before the COVID-19 pandemic. However, only a few of the assessed hand-washing procedures were altered due to the COVID-19 pandemic, indicating a lesser degree of behavioral change, in that case, between the two studied periods. Mobile phone cleaning/disinfection frequency also increased during COVID-19, while wet wipes and alcohol/alcohol solutions were the most preferred means used by students in order to clean/disinfect their mobile phones. Moreover, statistically significant differences were observed, between male and female participants, regarding their knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors on hand and mobile phone hygiene, followed by their faculty and year of studies. Overall, being a final-year female undergraduate student of health sciences has a positive influence on correct knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors on hand and mobile phone hygiene.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.G. and K.M.; Data curation, D.D. and V.C.; Formal analysis, D.D. and V.C.; Investigation, D.D.; Methodology, P.G.; Project administration, P.G. and K.M.; Resources, P.G.; Software, D.D. and V.C.; Supervision, P.G.; Validation, V.C., P.G. and K.M.; Visualization, D.D.; Writing—original draft, D.D.; Writing—review and editing, D.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the SPECIAL ACCOUNT FOR RESEARCH GRANTS—UNIVERSITY OF WEST ATTICA.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the UNIVERSITY OF WEST ATTICA (protocol code 99754/9 November 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The research data are available on request by contacting the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to sincerely thank the Rectorate of the International Hellenic University of Greece for granting permission to conduct our research at the premises of the Alexandreia campus, located in the area of Sindos—Thessaloniki Greece, as well as all of the students who participated in the study. We would also like to sincerely thank the research teams of Głabska et al. and Cicciarella Modica et al. for allowing us to use part of their research questionnaires’ questions for the composition of our study’s questionnaire.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Szeto, J.; Sidhu, B.; Shaw, F. Increased Organic Contamination Found on Mobile Phones after Touching It While Using the Toilet. BCIT Environ. Public Health J. 2015, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovca, A.; Rednak, B.; Godič Torkar, K.; Jevšnik, M.; Bauer, M. Students’ Mobile Phones-How Clean Are They? Sanit. Inženirstvo 2012, 6, 6–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, E.B.M.; Agnes, M.B.; Konkewicz, L.R.; Thomas, A.L.K.; Jacques, J.; Madeira, M.N. Analysis of the Presence of Organic Matter (ATP) in Mobile Devices of Healthcare Workers in Hospitals. Clin. Biomed. Res. 2017, 37, 38–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, H.S.; Abaza, A.F. Microbial Contamination of Mobile Phones in a Health Care Setting in Alexandria, Egypt. GMS Hyg. Infect. Control 2015, 10, Doc03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, S.K.; Pathak, V.K.; Kumar, M.M.; Raj, U.; Priya P, K. COVID-19 and Mobile Phone Hygiene in Healthcare Settings. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-H.; Chen, C.-J.; Wu, H.-Y.; Chen, I.; Chang, Y.-H.; Yang, P.-H.; Wang, T.-Y.; Chen, L.-C.; Liu, K.-T.; Yeh, I.-J.; et al. Plastic Wrap Combined with Alcohol Wiping Is an Effective Method of Preventing Bacterial Colonization on Mobile Phones. Medicine 2020, 99, e22910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kõljalg, S.; Mändar, R.; Sõber, T.; Rööp, T.; Mändar, R. High Level Bacterial Contamination of Secondary School Students’ Mobile Phones. Germs 2017, 7, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gonzáles, N.E.; Solorzano-Ibarra, F.; Cabrera-Díaz, E.; Gutiérrez-González, P.; Martínez-Chávez, L.; Pérez-Montaño, J.A.; Martínez-Cárdenas, C. Microbial Contamination on Cell Phones Used by Undergraduate Students. Can. J. Infect. Control 2017, 32, 211–216. [Google Scholar]

- Cicciarella Modica, D.; Maurici, M.; D’Alò, G.L.; Mozzetti, C.; Messina, A.; Distefano, A.; Pica, F.; De Filippis, P. Taking Screenshots of the Invisible: A Study on Bacterial Contamination of Mobile Phones from University Students of Healthcare Professions in Rome, Italy. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, I.; Raza, A.; Razaa, S.A.; Sadar, A.B.; Qureshi, A.U.; Talib, U.; Chi, G. Surface Microbiology of Smartphone Screen Protectors Among Healthcare Professionals. Cureus 2017, 9, e1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głąbska, D.; Skolmowska, D.; Guzek, D. Population-Based Study of the Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Hand Hygiene Behaviors—Polish Adolescents’ COVID-19 Experience (PLACE-19) Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounou, L.; Katelani, S.; Panagiotopoulou, K.-I.; Skouloudaki, A.-I.; Spyrou, V.; Orfanos, P.; Lagiou, P. Hand Hygiene Education of Greek Medical and Nursing Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 54, 103130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, C.; Cheung, K.L. Knowledge, Socio-Cognitive Perceptions and the Practice of Hand Hygiene and Social Distancing during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study of UK University Students. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickie, R.; Rasmussen, S.; Cain, R.; Williams, L.; MacKay, W. The Effects of Perceived Social Norms on Handwashing Behaviour in Students. Psychol. Health Med. 2018, 23, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergin, A.; Bostanci, M.; Onal, O.; Bozkurt, A.I.; Ergin, N. Evaluation of Students’ Social Hand Washing Knowledge, Practices, and Skills in a University Setting. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2011, 19, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbouthieu Teumta, G.M.; Niba, L.L.; Ncheuveu, N.T.; Ghumbemsitia, M.-T.; Itor, P.O.B.; Chongwain, P.; Navti, L.K. An Institution-Based Assessment of Students’ Hand Washing Behavior. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 7178645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.-H.; Cheong, H.-K.; Son, D.-Y.; Kim, S.-U.; Ha, C.-M. Perceptions and Behaviors Related to Hand Hygiene for the Prevention of H1N1 Influenza Transmission among Korean University Students during the Peak Pandemic Period. BMC Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van De Mortel, T.F.; Kermode, S.; Progano, T.; Sansoni, J. A Comparison of the Hand Hygiene Knowledge, Beliefs and Practices of Italian Nursing and Medical Students. J. Adv. Nurs. 2012, 68, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Villar, D.; Del-Moral-Luque, J.A.; San-Román-Montero, J.; Gil-de-Miguel, A.; Rodríguez-Caravaca, G.; Durán-Poveda, M. Hand hygiene compliance with hydroalcoholic solutions in medical students. Cross-sectional study. Rev. Esp. Quimioter. Publ. Of. Soc. Esp. Quimioter. 2019, 32, 232–237. [Google Scholar]

- Graf, K.; Chaberny, I.F.; Vonberg, R.-P. Beliefs about Hand Hygiene: A Survey in Medical Students in Their First Clinical Year. Am. J. Infect. Control 2011, 39, 885–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambil-Martin, J.; Fernandez-Prada, M.; Gonzalez-Cabrera, J.; Rodriguez-Lopez, C.; Almaraz-Gomez, A.; Lana-Perez, A.; Bueno-Cavanillas, A. Comparison of Knowledge, Attitudes and Hand Hygiene Behavioral Intention in Medical and Nursing Students. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2020, 61, E9–E14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skowron, K.; Bauza-Kaszewska, J.; Kraszewska, Z.; Wiktorczyk-Kapischke, N.; Grudlewska-Buda, K.; Kwiecińska-Piróg, J.; Wa\lecka-Zacharska, E.; Radtke, L.; Gospodarek-Komkowska, E. Human Skin Microbiome: Impact of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Factors on Skin Microbiota. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmonds-Wilson, S.L.; Nurinova, N.I.; Zapka, C.A.; Fierer, N.; Wilson, M. Review of Human Hand Microbiome Research. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2015, 80, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamadah, R.; Kharraz, R.; Alshanqity, A.; AlFawaz, D.; Eshaq, A.M.; Abu-Zaid, A. Hand Hygiene: Knowledge and Attitudes of Fourth-Year Clerkship Medical Students at Alfaisal University, College of Medicine, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2015, 7, e310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotfinejad, N.; Peters, A.; Tartari, E.; Fankhauser-Rodriguez, C.; Pires, D.; Pittet, D. Hand Hygiene in Health Care: 20 Years of Ongoing Advances and Perspectives. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, e209–e221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirose, R.; Ikegaya, H.; Naito, Y.; Watanabe, N.; Yoshida, T.; Bandou, R.; Daidoji, T.; Itoh, Y.; Nakaya, T. Survival of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and Influenza Virus on Human Skin: Importance of Hand Hygiene in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e4329–e4335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.S. Comparison of the Degree of Bacterial Removal by Hand Hygiene Products. J. Dent. Hyg. Sci. 2022, 22, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancholi, P.; Healy, M.; Bittner, T.; Webb, R.; Wu, F.; Aiello, A.; Larson, E.; Latta, P.D. Molecular Characterization of Hand Flora and Environmental Isolates in a Community Setting. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 5202–5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadow, J.F.; Altrichter, A.E.; Green, J.L. Mobile Phones Carry the Personal Microbiome of Their Owners. PeerJ 2014, 2, e447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M.; Campos, M.; Lohning, A.; Jones, P.; Legget, J.; Bannach-Brown, A.; McKirdy, S.; Alghafri, R.; Tajouri, L. Mobile Phones Represent a Pathway for Microbial Transmission: A Scoping Review. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 35, 101704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddell, S.; Goldie, S.; Hill, A.; Eagles, D.; Drew, T.W. The Effect of Temperature on Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 on Common Surfaces. Virol. J. 2020, 17, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillet, S.; Berthelot, P.; Gagneux-Brunon, A.; Mory, O.; Gay, C.; Viallon, A.; Lucht, F.; Pozzetto, B.; Botelho-Nevers, E. Contamination of Healthcare Workers’ Mobile Phones by Epidemic Viruses. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016, 22, 456.e1–456.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantais, A.; Grattard, F.; Gagnaire, J.; Mory, O.; Plat, A.; Lleres-Vadeboin, M.; Berthelot, P.; Bourlet, T.; Botelho-Nevers, E.; Pozzetto, B.; et al. Longitudinal Study of Viral and Bacterial Contamination of Hospital Pediatricians’ Mobile Phones. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meltzer, E.; Regev-Yochay, G. Mobile Phones and Respiratory Viral Infections. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 224, 1629–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Bueno de Mesquita, P.J.; Leung, N.H.L.; Adenaiye, O.; Tai, S.; Frieman, M.B.; Hong, F.; Chu, D.K.W.; Ip, D.K.M.; Cowling, B.J.; et al. Viral RNA and Infectious Influenza Virus on Mobile Phones of Patients with Influenza in Hong Kong and the United States. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 224, 1730–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corpet, D.E. Why Does SARS-CoV-2 Survive Longer on Plastic than on Paper? Med. Hypotheses 2021, 146, 110429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, A.W.H.; Chu, J.T.S.; Perera, M.R.A.; Hui, K.P.Y.; Yen, H.-L.; Chan, M.C.W.; Peiris, M.; Poon, L.L.M. Stability of SARS-CoV-2 in Different Environmental Conditions. Lancet Microbe 2020, 1, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Q.; Zubair, F.; Asif, A.; Khan, J.K.; Imran, F. Microbial Contamination of Mobile Phone and Its Hygiene Practices by Medical Students and Doctors in a Tertiary Care Hospital: A Cross-Sectional Study. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. Update 2021, 1, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zil-E-Ali, A.; Cheema, M.A.; Wajih Ullah, M.; Ghulam, H.; Tariq, M. A Survey of Handwashing Knowledge and Attitudes among the Healthcare Professionals in Lahore, Pakistan. Cureus 2017, 9, e1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L.J.; McEnroe-Petitte, D.M.; van de Mortel, T.; Nasirudeen, A.M.A. A Systematic Review on Hand Hygiene Knowledge and Compliance in Student Nurses. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2018, 65, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüttpelz-Brauns, K.; Obertacke, U.; Kaden, J.; Hagl, C.I. Association between Students’ Personality Traits and Hand Hygiene Compliance during Objective Standardized Clinical Examinations. J. Hosp. Infect. 2015, 89, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakarman, M.A.; Baig, M.; Malik, A.A.; Gazzaz, Z.J.; Mostafa, M.M.; Zayed, M.A.; Balubaid, A.S.; Alzahrani, A.K. Hand Hygiene Knowledge and Attitude of Medical Students in Western Saudi Arabia. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baier, C.; Albrecht, U.-V.; Ebadi, E.; Vonberg, R.-P.; Schilke, R. Knowledge about Hand Hygiene in the Generation Z: A Questionnaire-Based Survey among Dental Students, Trainee Nurses and Medical Technical Assistants in Training. Am. J. Infect. Control 2020, 48, 708–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, R.; Razee, H.; Seale, H. Facilitators and Barriers around Teaching Concepts of Hand Hygiene to Undergraduate Medical Students. J. Hosp. Infect. 2014, 88, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barcenilla-Guitard, M.; Espart, A. Influence of Gender, Age and Field of Study on Hand Hygiene in Young Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study in the COVID-19 Pandemic Context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 13016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erasmus, V.; Otto, S.; De Roos, E.; van Eijsden, R.; Vos, M.C.; Burdorf, A.; van Beeck, E. Assessment of Correlates of Hand Hygiene Compliance among Final Year Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Study in the Netherlands. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e029484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althubaiti, A. Information Bias in Health Research: Definition, Pitfalls, and Adjustment Methods. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2016, 9, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savitz, D.A.; Wellenius, G.A. Can Cross-Sectional Studies Contribute to Causal Inference? It Depends. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2022, kwac037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, J.; Putnick, D.L.; Bornstein, M.H. More than Just Convenient: The Scientific Merits of Homogeneous Convenience Samples. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 2017, 82, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).