Explain Again: Why Are We Vaccinating Young Children against COVID-19?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- COVID-19 (SARS-CoV2) can make children very sick and cause children to be hospitalized. In some situations, the complications from infection can lead to death.

- Children are as likely to be infected with COVID-19 (SARS-CoV2) as adults.

- Children can get very sick from COVID-19.

- Children can have both short and long-term health complications from COVID-19.

- Children can spread COVID-19 (SARS-CoV2) to others, including at home and school.

- COVID-19 (SARS-CoV2 infection) is usually mild in most children, but it can make some children unwell.

- One dose of the COVID-19 vaccine gives good protection against your child getting seriously ill, but two doses give stronger and longer-lasting protection.

- Vaccinating children can also help stop the spread of COVID-19 (SARS-CoV2) to other people, including within schools.

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results & Discussion

- The CDC estimates that from the 2010–2011 season to the 2019–2020 season, flu-related hospitalizations among children younger than 5 years old have ranged from 7000 to 26,000 in the United States.

- From the 2004–2005 season to the 2019–2020 season, flu-related deaths in children reported to CDC during regular flu seasons have ranged from 37 to 199 deaths. (During the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, 358 pediatric flu-related deaths were reported to CDC from April 2009 to September 2010.)

- Also of note, even though individual flu deaths in children must be reported to CDC, “it is likely that not all deaths are captured and that the number of actual deaths is higher. CDC has developed statistical models that account for the underreporting of flu-related deaths in children to estimate the actual number of deaths. During 2019–2020, for example, 199 deaths in children were reported to CDC but statistical modelling suggests approximately 434 deaths may have occurred” [6].

- It does not benefit them now [23];

- It will not benefit them in the future (as the systemic immunity will not last them into an adult age group that is susceptible) [15];

- It is NOT effectively contributing to any sensible global viral eradication program of the SARS-CoV2 viruses [20].

- Antibody mediated (mostly IgE) hypersensitivity reactions, predominately arising from sensitivity developed to carrier oils and adjuvants in the vaccine formulations. Symptoms usually manifest within minutes and hours [25].

- Delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions (type IV hypersensitivity); T-cell mediated reactions that can be both CD4+ and/or CD8+ dependent, with a target allergen presented via major histocompatibility molecules to T-cell receptors. Activation of CD4+ T cells results in cytokine mediated inflammation, which is typically confined to a local area, but can sometimes be widespread. In reactions where CD8+ T cells are involved, the release of perforin and granzyme can lead to bystander cell injury and death by apoptosis [26]. Symptoms of delayed hypersensitivity generally have onset within 6 h to weeks and can range widely from localized skin symptoms to disseminated rashes with systemic symptoms and/or blistering of the skin and mucosal surfaces [27].

- Immunologically mediated neurological complications: such as Guillain–Barré syndrome, Muller Fisher syndrome and other demyelinating neuropathies (Bell’s palsy, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, etc.) are known adverse events related to immunization [28,29]. These can be ongoing for many months and years.

- Antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE); whole dead virion protein vaccination can prime a new pathway by which a virus can propagate and spread within immune cells enabled by antibody mediated opsonization (ADE), thereby exacerbating severe illness caused by the viral infection in certain immunized individuals [30]. This is generally screened for very early in vaccine research and development [31].

4. Conclusions

- This study revealed that mRNA vaccine effectiveness against hospitalization during the Omicron variant surge declined from 85% to 73% for children aged 12 to 17.

- Amongst children aged 5 to 11, effectiveness fell even more significantly, from 100% to 48%.

- Vaccine effectiveness against testing positive declined from 66% to 51% among children aged 12 to 17. In the 5 to 11 years group, effectiveness dropped from 68% to 12%.

- In the last week of January, vaccine effectiveness against infection among 12-year-olds was 67%, but substantially lower at just 11% for 11-year-olds.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vashishtha, V.M.; Kumar, P. Emergency use authorisation of Covid-19 vaccines:An ethical conundrum. Indian J. Med. Ethics 2021, 6, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Hasegawa, K.; Ma, B.; Fujiogi, M.; Camargo, C.A.; Liang, L. Association of obesity and its genetic predisposition with the risk of severe COVID-19: Analysis of population-based cohort data. Metabolism 2020, 112, 154345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/recommendations/children-teens.html (accessed on 6 February 2022).

- Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coronavirus-covid-19/coronavirus-vaccination/coronavirus-vaccine-for-children-aged-12-to-15/ (accessed on 6 February 2022).

- Cunningham, R.M.; Walton, M.A.; Carter, P.M. The Major Causes of Death in Children and Adolescents in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2468–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/spotlights/2020-2021/pediatric-flu-deaths-reach-new-high.htm (accessed on 6 February 2022).

- Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/2018-2019.html (accessed on 6 February 2022).

- Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/aboutus/transparencyandgovernance/freedomofinformationfoi/covid19deathsinukforchildrenfromages0to19sincemarch2020 (accessed on 6 February 2022).

- Cromer, D.; van Hoek, A.J.; Jit, M.; Edmunds, W.J.; Fleming, D.; Miller, E. The burden of influenza in England by age and clinical risk group: A statistical analysis to inform vaccine policy. J. Infect. 2014, 68, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/aboutus/transparencyandgovernance/freedomofinformationfoi/deathsfrominfluenzaonlyin2019and2020intheuk (accessed on 6 February 2022).

- Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/281174/uk-population-by-age/ (accessed on 6 February 2022).

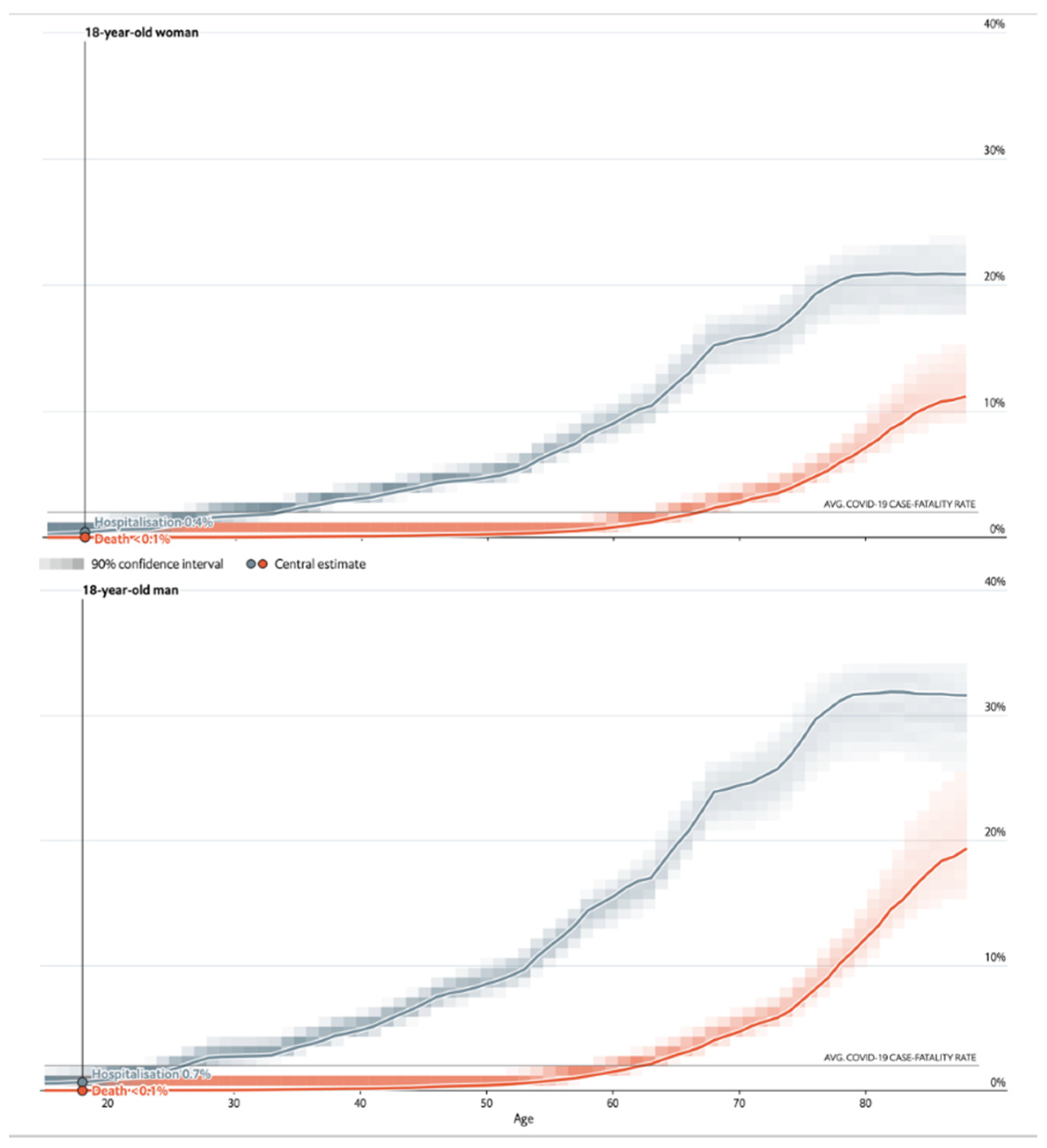

- See How Age and Illnesses Change the Risk of Dying from Covid-The Economist. Available online: https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/covid-pandemic-mortality-risk-estimator (accessed on 11 March 2021).

- Available online: https://covid19researchdatabase.org/ (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Vahidy, F.S.; Pischel, L.; Tano, M.E.; Pan, A.P.; Boom, M.L.; Sostman, H.D.; Nasir, K.; Saad, B. Real World Effectiveness of COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines against Hospitalizations and Deaths in the United States. Ome Medrxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edridge, A.W.D.; Kaczorowska, J.; Hoste, A.C.R.; Bakker, M.; Klein, M.; Loens, K.; Jebbink, M.F.; Matser, A.; Kinsella, C.M.; Rueda, P.; et al. Seasonal coronavirus protective immunity is short-lasting. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1691–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekine, T.; Perez-Potti, A.; Rivera-Ballesteros, O.; Strålin, K.; Gorin, J.-B.; Olsson, A.; Llewellyn-Lacey, S.; Kamal, H.; Bogdanovic, G.; Muschiol, S.; et al. Robust T Cell Immunity in Convalescent Individuals with Asymptomatic or Mild COVID-19. Cell 2020, 183, 158–168.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katikireddi, S.V.; Cerqueira-Silva, T.; Vasileiou, E.; Robertson, C.; Amele, S.; Pan, J.; Taylor, B.; Boaventura, V.; Werneck, G.L.; Flores-Ortiz, R.; et al. Two-dose ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine protection against COVID-19 hospital admissions and deaths over time: A retrospective, population-based cohort study in Scotland and Brazil. Lancet 2021, 399, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borio, L.L.; Bright, R.A.; Emanuel, E.J. A National Strategy for COVID-19 Medical Countermeasures. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2022, 327, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-age.html (accessed on 6 February 2022).

- Baker, R.E.; Park, S.W.; Wagner, C.E.; Metcalf, C.J.E. The limits of SARS-CoV-2 predictability. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 5, 1052–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/explorers/coronavirus-data-explorer? (accessed on 6 February 2022).

- Xiao, Y.; Li, Y.; Du, N.; Luo, L.; Su, D. Challenges facing Chinese primary care in the context of COVID-19. Fam. Pract. 2022, 179, 214–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostoff, R.N.; Calina, D.; Kanduc, D.; Briggs, M.B.; Vlachoyiannopoulos, P.; Svistunov, A.A.; Tsatsakis, A. Why are we vaccinating children against COVID-19? Toxicol. Rep. 2021, 8, 1665–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadri, S.S. Key Takeaways from the U.S. CDC’s 2019 Antibiotic Resistance Threats Report for Frontline Providers. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 48, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, C.A.; Rukasin, C.; Beachkofsky, T.M.; Phillips, E.J. Immune-mediated adverse reactions to vaccines. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 85, 2694–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justiz Vaillant, A.A.; Vashisht, R.; Zito, P.M. Immediate Hypersensitivity Reactions. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513315/ (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Williams, S.E.; Klein, N.P.; Halsey, N.; Dekker, C.L.; Baxter, R.P.; Marchant, C.D.; LaRussa, P.S.; Sparks, R.C.; Tokars, J.I.; Pahud, B.A.; et al. Overview of the Clinical Consult Case Review of adverse events following immunization: Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) network 2004–2009. Vaccine 2011, 29, 6920–6927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Phillips, E.J.; Bigliardi, P.L.; Bircher, A.J.; Broyles, A.; Chang, Y.-S.; Hung, S.-I.; Lehloenya, R.; Mockenhaupt, M.; Peter, J.; Pirmohamed, M.; et al. Controversies in drug allergy: Testing for delayed reactions. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 143, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gable, K.L.; Afshari, Z.; Sufit, R.L.; Allen, J.A. Distal Acquired Demyelinating Symmetric Neuropathy after Vaccination. J. Clin. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2013, 14, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, W.; Martina, B.; Rimmelzwaan, G.; Gruters, R.; Osterhaus, A. Vaccine-induced enhancement of viral infections. Vaccine 2009, 27, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata-Yoshikawa, N.; Shiwa, N.; Sekizuka, T.; Sano, K.; Ainai, A.; Hemmi, T.; Kataoka, M.; Kuroda, M.; Hasegawa, H.; Suzuki, T.; et al. A lethal mouse model for evaluating vaccine-associated enhanced respiratory disease during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabh3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://vaers.hhs.gov/index.html (accessed on 6 February 2022).

- Ferner, R.E.; Stevens, R.J.; Anton, C.; Aronson, J.K. Spontaneous Reporting to Regulatory Authorities of Suspected Adverse Drug Reactions to COVID-19 Vaccines Over Time: The Effect of Publicity. Drug Saf. 2022, 45, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patone, M.; Mei, X.W.; Handunnetthi, L.; Dixon, S.; Zaccardi, F.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Watkinson, P.; Khunti, K.; Anthony Harnden, A.; Coupland, C.A.C.; et al. Risk of myocarditis following sequential COVID-19 vaccinations by age and sex. Medrxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oster, M.E.; Shay, D.K.; Su, J.R.; Gee, J.; Creech, C.B.; Broder, K.R.; Edwards, K.; Soslow, J.H.; Dendy, J.M.; Schlaudecker, E.; et al. Myocarditis Cases Reported After mRNA-Based COVID-19 Vaccination in the US from December 2020 to August 2021. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2022, 327, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-vaccine-adverse-reactions/coronavirus-vaccine-summary-of-yellow-card-reporting (accessed on 6 February 2022).

- Simons, M.R.; Zurynski, Y.; Cullis, J.; Morgan, M.; Davidson, A. Does evidence-based medicine training improve doctors’ knowledge, practice and patient outcomes? A systematic review of the evidence. Med. Teach. 2019, 41, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandi, A.; Shet, A. Why vaccines matter: Understanding the broader health, economic, and child development benefits of routine vaccination. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 1900–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-12-2019-more-than-140-000-die-from-measles-as-cases-surge-worldwide (accessed on 6 February 2022).

- Feemster, K.A.; Szipszky, C. Resurgence of measles in the United States: How did we get here? Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2020, 32, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drew, L. The case for mandatory vaccination. Nature 2019, 575, S58–S60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kozlov, M. What COVID vaccines for young kids could mean for the pandemic. Nature 2021, 599, 18–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorabawila, V.; Hoefer, D.; Bauer, U.E.; Bassett, M.T.; Lutterloh, E.; Rosenberg, E.S. Effectiveness of the BNT162b2 vaccine among children 5–11 and 12–17 years in New York after the Emergence of the Omicron Variant. medRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Infections | Hospitalizations | Deaths | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV2 * | 1 million/28 million (3.5%) | 4150/28 million (0.015%) | 50/28 million (0.00018%) |

| Influenza ** | 3 million/28 million (10%) | 9800/28 million (0.035%) | 78/28 million (0.00028%) |

| AGE (Years) | Age Specific UK Population | Respiratory Virus | Annual Deaths 2019–2021 | Mortality Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 to 14 | 11,975,000 | SARS-CoV2 | 11.25 | 0.000094% |

| Influenza | 26 | 0.00022% | ||

| 15–19 | 3,651,000 | SARS-CoV2 | 16.5 | 0.00045% |

| Influenza | 4 | 0.00011% |

| Rate Compared to 18–29 Yeasrs old 1 | 0–4 Years Old | 5–17 Years Old | 18–29 Years Old | 30–39 Years Old | 40–49 Years Old | 50–64 Years Old | 65–74 Years Old | 75–84 Years Old | 85+ Years Old |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases 2 | <1× | 1× | Reference group | 1× | 1× | 1× | 1× | 1× | 1× |

| Hospitalization 3 | <1× | <1× | Reference group | 2× | 2× | 4× | 5× | 8× | 10× |

| Death 4 | <1× | <1× | Reference group | 4× | 10× | 25× | 65× | 140× | 340× |

| Vaccine | 1st and 2nd Doses | Booster | Adverse Reaction Reports | Deaths Soon after Vaccination ** | Myocarditis and Pericarditis | GB and MF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pfizer | 50.5 mil | 36.7 mil | 1,286,984 (2.55%) | 702 (0.0014%) | 1109 (0.0022%) | 92 (0.0002%) |

| Astra Zeneca | 46.7 mil | 231,168 (0.50%) | 1200 (0.0026%) | 425 (0.0009%) | 486 (0.0010%) | |

| Moderna | 3 mil | 32,936 (1.10%) | 33 (0.0011%) | 283 (0.0094%) | 12 (0.0004%) | |

| All | 136.9 million COVID-19 vaccination doses | 1,552,248 * (1.13%) | 1972 ** (0.0014%) | 130 per 100,000 (expect 37–47 per 100,000) | 40 per 100,000 (expect 2 per 100,000) | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iles, R.K.; Makhzoumi, T.S. Explain Again: Why Are We Vaccinating Young Children against COVID-19? COVID 2022, 2, 492-500. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid2040036

Iles RK, Makhzoumi TS. Explain Again: Why Are We Vaccinating Young Children against COVID-19? COVID. 2022; 2(4):492-500. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid2040036

Chicago/Turabian StyleIles, Ray Kruse, and Tarek Sultani Makhzoumi. 2022. "Explain Again: Why Are We Vaccinating Young Children against COVID-19?" COVID 2, no. 4: 492-500. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid2040036

APA StyleIles, R. K., & Makhzoumi, T. S. (2022). Explain Again: Why Are We Vaccinating Young Children against COVID-19? COVID, 2(4), 492-500. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid2040036