Abstract

A systematic review of the literature investigating the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychological and psychosocial factors was completed. Published literature was examined using electronic databases to search psychosocial factors such as beliefs and media persuasion, social support, coping, risk perception, and compliance and social distancing; and psychological factors as anxiety, stress, depression, and other consequences of COVID-19 that impacted mental health among the pandemic. A total of 294 papers referring to the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (December 2019–June 2020) were selected for the review. The findings suggested a general deterioration of mental health, delineating a sort of “psychological COVID-19 syndrome”, characterized by increased anxiety, stress, and depression, and decreased well-being and sleep quality. The COVID-19 effect on the psychological dimensions of interest was not the same for everyone. Indeed, some socio-demographic variables exacerbated mental health repercussions that occurred due to the pandemic. In particular, healthcare workers and young women (especially those in postpartum condition) with low income and low levels of education have been shown to be the least resilient to the consequences of the pandemic.

1. Introduction

As of 21 February 2022, SARS-CoV-2 has infected more than 423 million individuals worldwide and caused more than 5.8 million deaths [1]. During the first months of 2020, the globe was under lockdown: the confinement measures which constituted an emergency protocol imposing restrictions on the free movement of persons [2]. These restrictive measures had various effects on people’s daily life, and physical and mental health. This review arose from the need to summarize and schematize the many psychological publications related to the first wave of COVID-19, as they appear to be very large. The authors aim to provide a complete review of the literature on the psychological impact that the first wave (December 2019–June 2020) of COVID-19 had on a global level, to identify which factors related to the pandemic were most impacting people’s mental health.

The results of the review regard the first wave of the pandemic (2019–2020). Therefore, this impact is unrepeatable in the future, also regarding resilience and transformative resilience. The findings could indicate a specific structure that could be attributed to a “psychological COVID-19 syndrome”, characterized by symptoms relatable to anxiety, depression, stress, less wellbeing and more sleep problems.

We chose to analyze different variables of mental health studied in previous pandemics (Ebola, SARS, MERS, Novel influenza A, Equine influenza, etc.), in addition to psychosocial dimensions which proved to be essential to mitigate the spread of Coronavirus [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. The authors decided to build on the dimensions considered in previous pandemics to observe whether these variables were also present in the current COVID-19 pandemic. For easy reading of the review, we divided the work into two sections: (1) Psychosocial Variables, and (2) Observables related with Mental Health.

For this systematic review, 294 articles published between December 2019 and June 2020 were analyzed, resulting in a large, heterogeneous literature, with a total sample of 732,852 subjects from more than 30 countries. Although the collected works are often based on non-representative samples, their large number and the possibility of cross-referencing the results common to these studies allows on the one hand to overcome the possible problem of unrepresentativeness, and on the other to grasp the existence of an effect, assuming the heterogeneity of the samples used by these works.

The authors hypothesize that from this systematic review can be derived the psychosocial and psychopathological areas most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, and likewise, that can be delineated a profile of the most vulnerable individual to these types of issues. So, in this perspective, this review can be useful both for future research and for the current management of the pandemic emergency.

2. Review Methodology

In this section, details about the systematic review approach are provided. We relied on an adapted version of the systematic qualitative review approach by Higgins and colleagues [11]. The authors searched all the papers that included the relationship between COVID-19 and psychological variables of interest.

As a first step, we asked academic information specialists to search for COVID-19 scientific papers that fulfilled our inclusion criteria. These were: written in English language; published between December, 2019 and June, 2020; being an empirical study, project report or review; published in a scholarly peer-reviewed journal and/or conference proceedings; those related to psychological dimensions and mental health (i.e., psychological disorders, risk perception, beliefs, coping, compliance, social support).

The specialists completed their task consulting the databases of PsycInfo, PsycArticles, PubMed, Science Direct, PsyArXiv, NCBI, medRxiv, and Elsevier repository. The authors on their part contributed to the search by consulting Google and Google Scholar to increase the chances of identifying the widest range of sources possible. The consultation took place between April and May 2020. A total of 7381 sources were considered. Subsequently, the authors’ results were compared with those of the experts, and duplicates were removed. To select the papers, search terms such as “COVID-19”, “Psychology”, “Psychological”, “Psychological effect”, “Mental health” were included in the research. For a more complete list of all the search terms, see Appendix A. Based on the inclusion criteria, only 480 sources were accessed as full-text: 303 papers were eligible since they met the inclusion criteria.

At the title review stage, sources were most commonly rejected because they fulfilled two or more of the following exclusion criteria: were only citations, commentary, or books; were papers published before 2019; those not related to the psychological dimensions and mental health (i.e., psychological disorders, risk perception, beliefs, coping, compliance, social support); articles not in English language. At the abstract and full paper review stages, papers were most commonly rejected for: demonstrating no inclusion of a psychological variable, having incomplete results, using qualitative measures and articles where data analysis was not suitable for the systematic review process (e.g., lack of descriptive statistics, no correlation coefficients provided for the variables of interest).

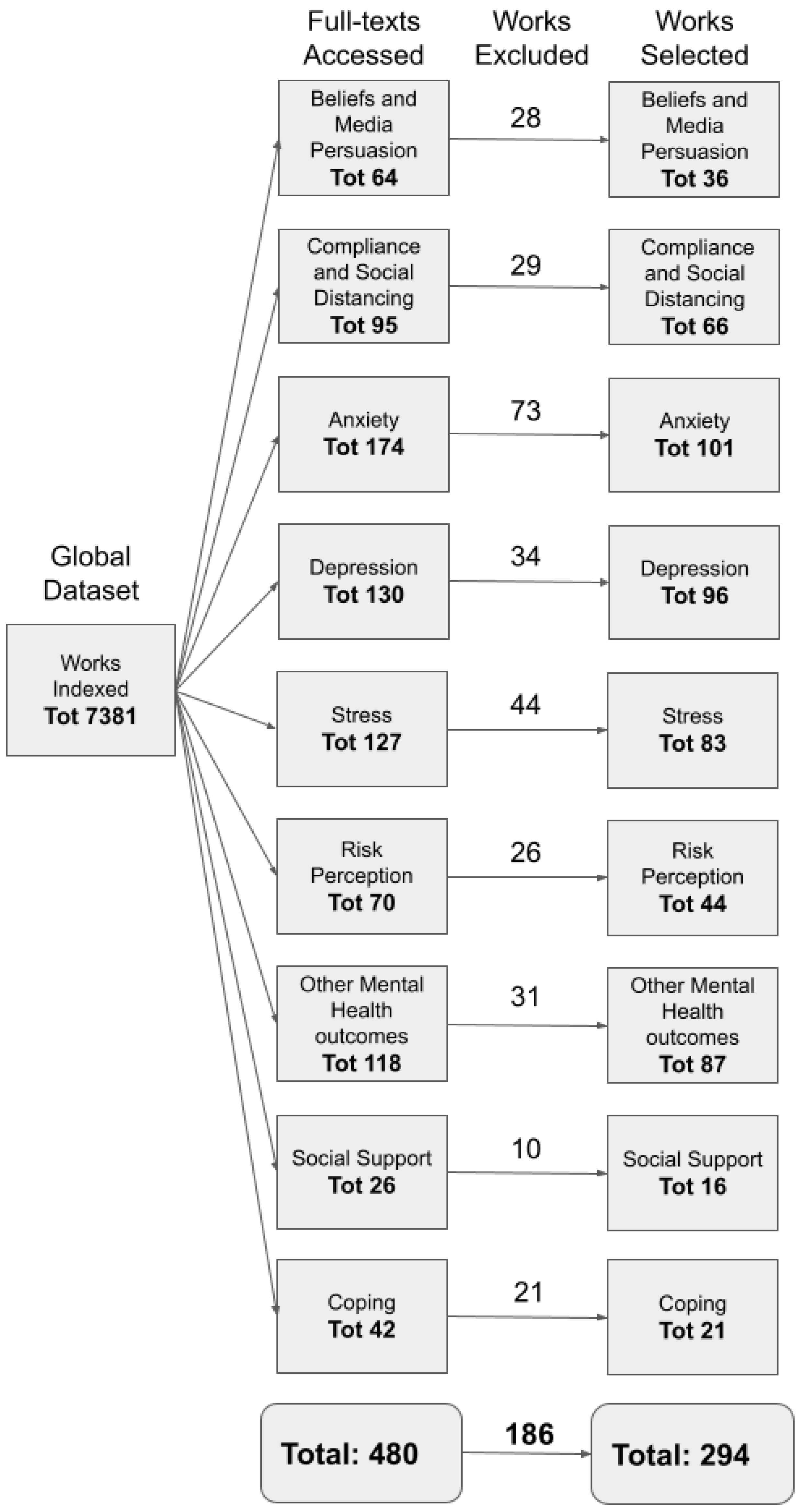

A flow diagram of the systematic search is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Diagram showing the information flow through the review: the number of works identified, included and excluded.

This review is divided into two main sections: (1) Psychosocial Variables, and (2) Observables related to Mental Health. The first section is in turn divided into different subsections: Beliefs and Media Persuasion, Social Support, Coping, Risk Perception, and Compliance and Social Distancing. The second section is in turn divided into different subsections: Anxiety, Stress, Depression, and Other consequences of COVID-19 on Mental Health. These are the dimensions that emerged most during the analysis of the literature about COVID-19. The subdivision in these paragraphs was formulated to make reading easier. Every subsection is divided into “Introduction ”, “Measures”, and “Results”.

Postponed to the “Discussion” paragraph is the possibility of connecting in a single design all the results emerging from the various sections, towards a definition of a psychological COVID-19 syndrome. For an easier reading, you can consult Table A1 (placed in the Appendix A) that contains the main information of the papers analyzed.

8. Mental Health Variables: Anxiety

8.1. Introduction

We chose to analyze anxiety because research on past epidemics, like SARS, MERS, swine flu and Ebola, revealed a wide range of negative psychosocial impacts, of which anxiety was one of the main outcomes [7,37,183,184,185,186]. In particular, the quarantine had a huge impact on people: when comparing quarantined versus non-quarantined individuals, the first were more likely to show psychological distress and to have a high prevalence of psychological symptomatology [187]. A recent study about the COVID-19 emergency indicated that “53.8% of respondents rated the psychological impact of the outbreak as moderate or severe; (…) 28.8% of respondents reported moderate to severe anxiety symptoms” [186].

Additionally, uncertainty may exacerbate the already existing detrimental effect of the pandemic on anxiety [188]. Anxiety is not just an outcome of the pandemic but could also have repercussions on behaviours implemented during the pandemic.

In the work of [185], it emerged that high and low anxiety individuals [189] behaved differently on some specific COVID-19 related conducts. High anxiety individuals may cause crowding (and thus increase the likelihood of infection), but at the same time they may be reluctant to seek medical assistance for fear of transmission, whereas individuals with low anxiety were found reluctant to comply with preventive measures [185].

8.2. Measures

The already validated questionnaires used to measure anxiety are reported in Table 11.

Table 11.

Validated tools to measure “Anxiety”. In the table are reported the psychological tools adopted by the studies taken into account, their internal consistency (reliability), and their frequency.

Only four papers decided to use ad hoc measures for anxiety [16,41,161,211].

8.3. Results for Anxiety

Fitzpatrick et al. (2020) [212] and Guo et al. (2020) [213] highlighted high and medium levels of anxiety in the USA and China populations. Pandemic related distress was associated with anxiety: specifically, perceiving symptoms of COVID-19 (fever, cough, etc.), loneliness and stress increased anxiety levels [214,215].

Following protective measures, like mask-wearing and handwashing, were related to lower anxiety levels [23,168,216]. Nonetheless, adopting these protections appeared as not enough for drastically lowering anxiety; instead, adhering to social isolation policies appeared as essentials to reduce anxiety levels [38].

Anxiety was also increased by social contexts. People who knew someone infected by COVID-19 [7,58,110,217,218,219,220] reported a higher level of anxiety. Anxiety was also higher in people with a positive COVID-19 diagnosis [201,221,222,223]. Unexpectedly, longer periods of lockdown did not lead to high anxiety levels [119,224,225].

Individuals with a higher level of COVID-19 knowledge were more likely to report a higher level of anxiety [16,23,41,157], but, despite this, up-to-date and accurate health information, along with being aware of the risks of the pandemic, were protective factors against the pandemic’s psychological burden [186,226]. The exposure time to COVID-19 information was associated with greater anxiety levels [211,216,226,227], as well as worries and concerns about COVID-19 [37,118,223,228,229].

Risk perception also played a role in shaping people’s anxiety in the pandemic scenario. Indeed, people who perceived a high risk and a realistic high threat reported higher levels of anxiety [6,96,122,133,230].

Anxiety was also studied and investigated in some specific populations, like medical-care workers. Several papers analyzed samples composed healthcare personnel (doctors, nurses, physical therapists etc.), finding a high prevalence of anxiety symptoms [70,157,220,222,231,232,233,234,235]. Although, according to [8], there was no significant difference in anxiety levels among doctors, nurses and pharmacists. Instead, the essential aspect that appeared to affect healthcare personnel anxiety levels is the time spent in the hospital [72]. In addition, healthcare workers who believed the virus was developed in a lab reported higher levels of anxiety [235].

In conclusion, several studies found that lower anxiety was associated with a higher life satisfaction [236,237], higher crisis management appraise [238], higher perceived level of health [7], a higher number of leisure activities [7], more physical activity and exercise [226,239,240] and resilience [24,133,229]. Instead, higher anxiety was associated with loneliness [24], bad distress tolerance [24], more significant changes in daily life [7], paralyzing worry [229], reduced appetite [229], and engagement in COVID-19 prosocial acts [64].

Anxiety levels during the pandemic were associated with age, gender, social condition, socio-demographic variables, culture and psychological variables. The results are shown below.

Age: 21 papers found a strong relation between anxiety and age [4,118,143,157,187,221,222,224,225,239,241,242,243,244,245,246,247,248,249,250,251,251]. Specifically, 16 reports claimed that younger age seems to be associated with higher anxiety [4,118,187,201,221,224,225,239,241,242,243,244,245,247,248,249,251,252,253]. Only three papers argued the opposite [222,246,254]. Instead, specific anxiety for COVID-19 was higher with older age [248].

Gender: There are numerous articles that have found a strong correlation between gender and anxiety [4,157,255,256,257]. In almost all articles, the female gender was associated with a higher level of anxiety than men [8,16,67,104,161,185,187,221,222,225,233,242,243,244,245,250,258,259,260,261,262,263]. Females reported being more influenced by anxiety and experiencing more negative emotion [161]. Just one article seems to find mixed results, reporting higher GAD-7 scores for males than females [263].

Social Condition: Several studies have shown that a higher level of education is correlated with an increased anxiety about COVID-19 [67,201], particularly individuals with a lower level of education than middle school are more anxious [224]. Other studies show that high levels of anxiety appear to be income-related: lower income leads to higher levels of anxiety [187,233,248,256].

Socio-demographic variables: Research shows that unemployment, self-employment, private sector employment, lack of formal education, family size, and paternity (>2 children) were associated with a higher likelihood of negative mental health [247]. The confidence in the physician’s ability to diagnose COVID-19 infection, the decrease in the probability of contracting it and the lower frequency of seeking information about it, because of satisfaction with the information received, have been protective factors against negative mental health, like anxiety [247]. Another protective factor against COVID-19 anxiety is living in urban areas and living with parents [58]. Instead, longer working time and more years of work increased the risk of anxiety [220,261]. Finally, living in heavily crowded areas, where the social distancing requirements are lacking, could lead to higher levels of anxiety [264]. Students, especially abroad ones [54], experienced relatively greater anxiety during the period of the epidemic [7,265], except if they considered themselves healthy [155]. Research has also observed that levels of anxiety among medical students have decreased with the introduction of distance learning [37].

Culture: Only Liu et al. [24] investigated and found significant differences possibly due to culture diversity. In their study, Asian Americans, Hispanic/Latinos reported lower anxiety levels than Whites [24].

Comorbidity: Anxiety measured during COVID-19 epidemic showed different comorbidity effects [55,56,58,67,70,221,229,262,266,267,268]. People with psychological anxiety disorders appeared more vulnerable to the impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on their mental health in terms of well-being and quality of life [220,221]. Anxiety during the COVID-19 epidemic was associated with negative affect [269], PTSD symptoms [268] and risk of postpartum depression [266,267]. The well known relationship between anxiety and sleep disorders [188] seemed to be confirmed also about Coronavirus specific anxiety. Indeed, Coronavirus anxiety levels were higher in people with sleep disorders (like insomnia) and poor sleep quality [70,99,188,227,270,271,272]. Only one article [273] found no significant correlation between anxiety and sleep disorders.

Table 12 shows information about the papers analyzed for the study of anxiety.

Table 12.

Anxiety. Summary of sources, with the number of papers analyzed, the total sample size, the provenance of the sample and the mediator variables. “MTurk” is used to indicate a sample extended worldwide.

9. Mental Health Variables: Stress

9.1. Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak has caused public panic and mental health stress [10]. McEwen and colleagues [274] defined stress as an adaptive psycho-physical reaction in response to a physical, social or psychological stimulus, called a “stressor”. Stress-related responses are cognitive, emotional, behavioural and physiological [74,275]. During the first wave, the pandemic had an unprecedented impact on social lives around the world and can be viewed as a global stressor induced, beyond the risk for health, by the social isolation and distancing measures [276,277,278]. There is a lack of psychological literature related to epidemics (e.g., Ebola, Swine flu) or global pandemics; the last pandemic was the Spanish Flu of 1918, but there is not enough research about this [6]. The few recent studies about epidemics noted that there was increased stress due to the epidemic and quarantine [247]. Quarantine has been associated with high stress levels, depression, anxiety, irritability, insomnia, burnout, and physical symptoms [6,38,75,225,279]. Furthermore, being quarantined is associated with acute stress and trauma-related disorders, like Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) [57,75,225,280,281,282,283]. In particular, during the first wave of COVID-19, PTSD appeared as characterized by involuntary memories of the trauma such as intrusions or nightmares, persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the traumatic event, negative alterations in cognitions and mood that are associated with the trauma, as well as alterations in arousal and reactivity that are associated with the trauma [281,283]. Those populations who were more at risk, such as health workers, were more likely to develop this kind of disorder [10,57,225,284].

Moreover, the disruptive changes of the work market also led to higher general levels of stress [285]. For instance, many people had lost their jobs because of the pandemic, others had to work from home while taking care of the family (i.e., remote working) [7], especially teachers who were forced to rely on information and communication technology (ICT) despite their technological literacy and/or fluency [286]. In particular, this pandemic seemed to psychologically affect healthcare providers and other workers, since they were on the front line [284]. Additional factors that seem to exacerbate stress levels in the population during isolation or quarantine [287] were an incorrect perception about the transmission of the virus [288] and conspiratorial beliefs [46].

9.2. Measures

The validated questionnaires used to measure stress are reported in Table 13.

Table 13.

Validated tools to measure “Stress”. In the table are reported the psychological tools adopted by the studies taken into account, their internal consistency (reliability), and their frequency. 1: Modified version of PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 [289]; 2: adapted from the 14–item Perceived Stress Scale [290].

9.3. Results for Stress

The COVID-19 pandemic and the consequent lockdown period increased the level of stress in the population [5,7,78,259,307], and this was likely to increase as the number of lockdown days increased [287,308]. Higher levels of stress were associated with: loss of job/education [89,309], having to go out to work [187], having an acquaintance infected with COVID-19 [89,187,247], likelihood of contracting the virus [310], more hygiene behaviors [247,256,310], history of stressful situations [187], medical problems [74,187], risk perception and COVID-19 specific fear/worries [10,74,133,247,259,310], perception of changes in life [74], dysfunctional coping strategies (i.e., denial, substance use, behavioral disengagement) [55,74,245], loneliness [10], perceiving physical symptoms as COVID-19 [215], belief in conspiracy theories [46], low distress tolerance [10], low social support [10,55,276], and decreased sleep quality [271]. Protective factors for stress were associated with: resilience [259,311], greater social connectedness [276], seeking information on COVID-19 [74,89,183], up-to-date and accurate health information [186], functional coping styles (i.e., planning, religion) [74,245], internal locus of control [74], perception of being able to avoid the virus [74], satisfaction with life [237], personality traits (high agreeableness, high conscientiousness, high emotional stability and high extroversion) [74], less exposure to COVID-19 [233,273], and agreed/confidence with government measures [186,216,277]. Moreover, individuals who reported high levels of optimism, and reported that the lockdown situation also had positive aspects, had lower stress levels [277,312,313].

Interestingly, using the internet was positively associated with higher levels of stress [183,226,269,309]. For example, some studies showed that the use of social media (during the pandemic) was associated with symptoms of PTSD [183], because on these platforms there was information available that is not necessarily based on well-founded facts [226]. This could lead to confusion and uncertainty among individuals about the preventive measures taken to reduce the spread of the COVID-19 virus. The minimisation and unacceptability of the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic has been associated with stress [226]. When people reported more stress related to COVID-19, they felt less satisfied, less engaged, and more conflicted in their relationships [181]. For example, one study [7] saw how those who had a relationship without cohabitation perceived more individual and relational stress during lockdown [7].

The category of healthcare workers reported higher levels of stress [127,220,221,254,260,268,281,288]; and in particular, females reported to be more stressed than males [168,220,314]. According to [87], the main factors associated with stress were: concerns for personal safety, concerns for their families, and concerns for patient mortality; the factors that reduced stress were: correct guidance, and use of protective behaviors for prevention.

Furthermore, other studies showed correlations between stress and low social support [70], lack of psychological therapy [315], poor sleep quality [314], hyperarousal symptoms [314], risk perception [127], worries and knowledge about COVID-19 [127].

Finally, different studies showed that stress was strongly associated with symptoms of burnout (i.e., depersonalization, emotional exhaustion) [233,268,316]. In particular, females [279,284], those who were exposed to COVID-19 patients [285,316], and long-term workers [279,284] reported high levels of burnout.

Stress levels during the pandemic were associated with age, gender, social condition, culture and comorbidity. The results are shown below.

Age: results showed a significant impact of age on stress levels [74]. A lot of papers reported higher stress and PTSD levels among the younger individuals rather than the older one [7,75,118,187,243,247,258,260,277,308,317,318,319,320]. These results are not found within the medical staff sample [87].

Gender: numerous articles have reported a significant relation between gender and stress, with females reporting higher levels of stress and PTSD than males [10,74,186,187,220,221,225,237,242,243,247,252,259,260,277,281,282,309,317,319,320,321,322], in particular, women who have been in direct contact with a COVID-19 patient [260], or those who have a recent exposure history in Wuhan [282]. Accordingly to Newby and colleagues [310], not only women, but also those who identify as non-binary or with a different gender were associated with higher self-reported stress. Finally, Cai and colleagues [87] found that factors that could reduce stress (i.e., correct guidance and effective safeguards for prevention from disease transmission) had a larger impact on females than males.

Social Condition: people with lower education experienced higher levels of stress [74,252]. Regarding the difference between occupations, those who had undergone the greatest change in work, like medical staff and teachers, showed themselves as the most stressed [275,286,288]. Indeed, teachers and healthcare workers continued to work in emergency circumstances. Unemployment and discontinued working activity (working more) were also associated with higher stress [7,225,247,309]. Finally, lower incomes [56,233,247], student status [186,265,269,308,323], marital status [247,317], large families [74,317], and more years of working [220] were associated with more stress.

Culture: Geographical differences in the effect of the pandemic were few and fragmentary, but are reported below. Italian, Chinese, Nigerian and Aboriginal populations reported high prevalence of stress symptoms [231,280,310]. Australians were more stressed than the Chinese population, but less than Italians [256]. The Austrian population was less stressed than the Chinese population [226].

Comorbidity: During the COVID-19 pandemic, a significant positive correlation was observed between stress and depression [251,309,312], anxiety [251,312], sleep [283], physical illness [220,262,310,320,324], somatization [312], and history of mental disorders [220,259,310].

Table 14 shows information about the papers analyzed for the study of stress.

Table 14.

Stress. Summary of sources, with the number of papers analyzed, the total sample size, the provenance of the sample and the mediator variables. “MTurk” is used to indicate a sample extended worldwide.

10. Mental Health Variables: Depression

10.1. Introduction

Depressive disorder affects thoughts, emotions, and physical health to varying degrees [325], and it often manifests as low mood, slow thinking, decreased activity, and impaired cognitive function [253]. The consequences are quite serious, ranging from interruption of interpersonal relationships to lifelong mental illness and suicidal behavior [78,253,312,326]. Previous public health pandemics have been linked to an increase in mental health problems. For example, Ebola, SARS, MERS, novel influenza A, equine influenza outbreak seemed to be associated with higher levels of depression [4,6,157]. In line with previous epidemics, the COVID-19 pandemic showed a similar effect on depression [212,222,223,272,304]. In particular, quarantine and social isolation, but also the strict prevention and control requirements, and the patients’ lack of communication with the outside world, were associated with higher rates of psychological depressive symptoms [78,185,187,214,216,223,245,251,321,327].

The pandemic not only elicited symptoms of psychological distress in people with no previous history of depressive symptoms, but also worsened them in people with a history of psychiatric disorders such as depression [78,326]. Another source of depression symptoms was individuated by the literature in the constant exposure to information about COVID-19 [185,216], combined with the uncertainty of the situation [185,251,312]. Just one of 97 papers did not capture effects of the pandemic on depression levels [214].

10.2. Measures

The already validated questionnaires used to measure depression are reported in Table 15. Only two studies used ad hoc questionnaires to analyze depression [328,329].

Table 15.

Validated tools to measure “Depression”. In the table are reported the psychological tools adopted by the studies taken into account, their internal consistency (reliability), and their frequency.

10.3. Results for Depression

The influence of COVID-19 on depression levels is not solely attributable to the factors outlined in the introduction. There were a number of dynamics that still impact depression and were increased during the pandemic [6,212,259,310,328]. Among these factors were those related to aspects strictly connected with COVID-19 [24,111,133,157,214,215,220,225,240,243,269,345,346,347], risk perception and its reactions [96,111,129,133,143,216,247,256,309], low quality of life [55,157,214,243,259,312], and addictions [220,241].

Pregnancy was another area impacted by COVID-19, especially when it concerned depression, due to its nature as a special, but also critical, moment in womens’ lives [267]. In particular, WHO reported that about 10% of pregnant women experience a mental disorder, primarily depression [267], whose likelihood has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic [266,348,349]. Furthermore, for both pregnant women and their husbands, fear of COVID-19 was significantly associated with their depression level [191].

As for the COVID-19 pandemic effects on medical staff, there is some agreement between scholars. Some works highlighted that medical staff particularly suffered from the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of depression symptoms, due also to the increased work-related risks and workload [4,8,220,222,254]. In particular, medical staff members were more likely to have an impairment of their attention, cognitive functioning, and clinical decision-making [220]. Some others found that healthcare workers were at risk to develop depression [10,213,217,219,220,231,232,235,242,254,262,268,270,350]. However, other papers found the contrary [221,260], thus suggesting that the effect of the pandemic on the depression of health workers can be mediated by factors such as: longer average working time, more time in contact with COVID-19 patients, spending more time thinking about COVID-19, and spending more time searching for coronavirus information [217,219,270]. Some protective factors individuated specifically for healthcare workers were: maintaining contacts through social networks [265], individual resilience [281], distress tolerance [281], social support [65], and having a meaning in life [312].

Regarding the general population, literature identified a number of protective factors towards depression. In particular, resilience [24,133,259], sexual satisfaction [236], pandemic-related prosocial experiences [64], hope and zest [183], positive affect [96,243,351], confidence about overcoming COVID-19 pandemic [157,216,352], living farthest from the epidemic [273], high levels of family support [24,307], credibility of updates [216,247,352], home self-quarantine [269,352], having a garden [245], continuing to work [245], physical exercise [239,307], meaning in life [312], trust in medical staff [216,247], taking prevention measures [168], and optimism [307,312] were associated with lower depressive symptoms.

Depression levels during the pandemic were associated with age, gender, social condition, culture and psychological variables. The results are shown below.

Age: Age seemed to be significantly associated with depression [157]. Younger people reported a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic [4,7,184,221,225,235,239,242,243,245,247,248,249,258,347]. Conversely, older people showed lower depression levels [7].

Gender: The findings showed that women had higher levels of depression than men [4,8,10,67,157,186,187,220,221,222,225,239,242,243,247,254,255,258,259,260,262,272,307,321,347], in line with pre-COVID-19 literature [353,354]. A prolonged exposure to domestic hostility due to quarantine worsened the symptoms [259]. Just one research found the contrary [310].

Social Condition: An association between sociodemographic variables and depression was captured: lower levels of education, unemployment, lower income, living in urban areas, living in crowded areas where it is impossible to maintain social distance, not having a child, having an acquaintance infected with COVID-19 have been associated with higher levels of depression [6,8,67,185,187,226,233,245,247,248,253,264,347]. Remote working was associated with lower depressive symptoms [245], while being a student seemed to be significantly associated with higher levels of depression [4,8,186,254,265,310].

Culture: Some differences related to culture were found: during the COVID-19 pandemic, Chinese, Asian Americans, and Israeli Arabs were at low risk of present depressive symptoms, compared to Spanish, White Americans, and Israeli Jewish [7,24,355]. According to Gobbi and colleagues [326], Turkish had the lowest level of depression, compared to Canadians, Pakistanians, and Americans [326].

Comorbidity: Anxiety [38,96,223,345], stress [214,312], sleep difficulties [223,271], history of mental health issues and chronic illness [220,221,255,259,262,268,310,347,356] were consistent predictors of higher depression during COVID-19 pandemic. These results also are in line with pre-COVID-19 literature [353,354].

Table 16 shows information about the papers analyzed for the study of Depression.

Table 16.

Depression. Summary of sources, with the number of papers analyzed, the total sample size, the provenance of the sample and the mediator variables. “MTurk” is used to indicate a sample extended worldwide.

11. Mental Health Variables: Other Consequences of COVID-19 on Mental Health: Wellbeing, Psychological Distress, Fear of COVID-19 and Sleep

11.1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, as well as previous epidemics (such as SARS, H1N1, Ebola virus), have caused other psychological consequences with respect to those considered in the previous paragraphs, both on individuals affected by these diseases, as well as on the non-infected ones [3,5,8,9]. In particular, four constructs about Mental Health and Quality of Life domains will be examined below due to their connection with the COVID-19 outbreak.

Wellbeing: Living under the threat of the pandemic and its consequences represented a significant challenge to wellbeing [329,350,357]: indeed, the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic was linked to worsening in wellbeing and mental health [9,329,358]. The sudden outbreak of COVID-19 and the preventive measures had a strong impact reducing the quality of life of the population [5,93]: forcing a drastic change in habits and routines [359], reducing social contact [329], and restricting freedom of movement as a consequence of social isolation [5]. Both the sudden outbreak of a new and unknown virus and the measures adopted to decrease its spread have had a strong impact on the mental health and the psychological well-being of the population [5].

Psychological Distress: Variables positively associated with psychological wellbeing were negatively associated with psychological distress [360]. APA defined psychological distress as a set of painful mental and physical symptoms that are associated with normal fluctuations of mood in most people [361]. Furthermore, Arvids Dotter and colleagues [362] defined psychological distress as a state of emotional suffering associated with stressors and demands that are difficult to cope with in daily life. When facing something new or unknown, such as the COVID-19 virus, a lack of effective treatment can lead to psychological distress in health care professionals as well as in patients [362]. The risk of getting infected, the lockdown scenario, and the consequent changes in habits may contribute to feelings of loneliness (connected to social isolation) and psychological distress [5,359,363].

Risk factors associated with greater distress were: not having an adequate supply (of food or goods of first need) [364], quarantine [364,365], low level of health perception [364], risk control [364], risk perception [364], low social support (family) [363], negative coping styles [75], delay in returning to work and school [365], negative thoughts [366], being close to potential risk groups [9], and work environment [3]. In the pandemic, healthcare workers are at high risk of psychological distress [357]: they were worried about overtime work, the stigma of the illness, and the health of their families and themselves [279]. While, protective factors associated with distress were: taking personal prevention/protection and clothing disinfection measures, clear communication of directives, and precautionary measures [364].

Fear of COVID-19: Fear is a negative emotion accompanied by excessive levels of emotive avoidance concerning particular stimuli, and it is an adaptive danger response [133,178,367]. It is associated with clinical phobias [178], social anxiety [178], risk perception [367], health anxiety [367], bad psychological and physical health [133], use of social media [367], high neuroticism and worries [366]. However, fear to some extent can be helpful for people in terms of leading them to comply in protective behaviours against COVID-19 [107,133,178].

In particular, it is also necessary to define the fear of COVID-19, that is based on four basic pillars: fear of the body, significant others, uncertainty, and action/inaction [9,368]. Especially the uncertainty led to changes in habits that are associated with decreased wellbeing and increased psychological distress [9,178].

Sleep: Finally, sleep is an indispensable physiological process in maintaining physical health [369] and sleep quality is a key indicator of health [70]. The stressful situations caused by the COVID-19 pandemic appeared to enhance symptoms such as sleep suppression, increased wakefulness, insomnia, difficulty falling asleep, maintaining sleep, waking up early, daytime sleepiness, nightmares and daytime dysfunction, and other sleep-related disorders [69,70,188,273,283,369]. On the other side, social support appeared to reduce stress and consequently improve sleep quality, and also enhance wellbeing [70].

11.2. Measures

Wellbeing: The validated questionnaires used to measure wellbeing are reported in Table 17.

Table 17.

Validated tools to measure “Wellbeing”. In the table are reported the psychological tools adopted by the studies taken into account, their internal consistency (reliability), and their frequency.

Different research used ad hoc questionnaires to analyze wellbeing [17,38,122,212,233,329].

Distress: The validated questionnaires used to measure distress are reported in Table 18.

Table 18.

Validated tools to measure “Distress”. In the table are reported the psychological tools adopted by the studies taken into account, their internal consistency (reliability), and their frequency.

Different research used ad hoc questionnaires to analyze distress [8,45,90,166,310,363,366].

Fear of COVID-19: The validated questionnaires used to measure the fear of COVID-19 are reported in Table 19.

Table 19.

Validated tools to measure “Fear of COVID-19”. In the table are reported the psychological tools adopted by the studies taken into account, their internal consistency (reliability), and their frequency.

Different research used ad hoc questionnaires to analyze fear [37,107,133,212,277,390].

Sleep: The already validated questionnaires used to measure sleep are reported in Table 20.

Table 20.

Validated tools to measure “Sleep”. In the table are reported the psychological tools adopted by the studies taken into account, their internal consistency (reliability), and their frequency.

Different research used ad hoc questionnaires to analyze sleep quality [69,188,256,269,395].

11.3. Results for Other Consequences of COVID-19 on Mental Health

The influence of COVID-19 on the levels of wellbeing, distress, fear, and sleep appeared as mediated by different factors that are reported below.

Wellbeing: The initial stages of the pandemic had minimal detrimental effects on wellbeing [68]. Several studies found that quarantine [310,359], living in regions with higher COVID-19 prevalence [309], loneliness [214,329,396,397], risk perception [3,122], conspiracy beliefs [45], suspected infection [71], spending time searching for information about COVID-19 [71], searching information on social media [3,359], not practicing prevention measures [3], fear of COVID-19 [9,17,397,398], intolerance of uncertainty [9], rumination [9], exhaustion [397], internet addiction [357], work overload [398], stressful life events [357], negative coping styles [71,86,93], and substance use [93] were associated with lower levels of mental wellbeing. On the contrary, physical exercise [239,399], positive coping strategies (e.g., emotional support, humor, religion) [8,71,77,93], optimistic attitude [35] (Imtiaz et al., 2020a), hope [106,183,329], resilience [106,329], perception of effective protective measures [397], satisfaction at work [397], good social support [71,357,398], and higher self-efficacy [3,398] were associated with an increase of wellbeing levels.

Regarding healthcare workers, it is demonstrated that their workload had a significant negative impact on their psychological wellbeing [279,400].

Distress: Greater mental distress was evident post lockdown [8,214]. The decrease in distress during the initial phase was attributed to preventive measures (including medical support and resources to stop the spread of the virus) [304]. Among the healthcare workers, high levels of distress were found [90,397,401,402], finding also that those who believed the virus was developed intentionally in a lab reported higher levels of distress [401].

Fear: Regarding the fear of COVID-19, it was associated with psychological distress and life satisfaction [170,228,403]: this was a mediating factor between intolerance of uncertainty and wellbeing [9]. According to Mertens and colleagues [367], there are four predictors of the fear of COVID-19: health anxiety, regular media use, social media use, and risks for loved ones [367]. Nevertheless, COVID-19 fear has been shown to predict positive changes in behavior (social distancing, hand hygiene) [107,170,178,390]. Furthermore, people who had higher levels of risk perception experienced more fear, and they were more inclined to develop a mental disorder [133,228]. Finally, between healthcare workers there was also a negative correlation between fear of COVID-19 and wellbeing [279,400,403,404].

Sleep: Reporting sleep-related functional problems was significantly associated with higher distress [397]. During quarantine, sleep timing markedly changed: people went to bed and woke up later, and spent more time in bed, but, paradoxically, also reported a lower sleep quality [271]. The difficulty in falling asleep was the result of an increase of “presleep cognitions”, which could probably lead to PTSD [283]. According to Di and colleagues, and Bai and colleagues [395,405], even children reported sleep difficulties during the COVID-19 pandemic [395,405]. In particular, sleep disorders were higher in COVID-19 confirmed cases [223], and those who had adversity experiences/worries [69], no exercise [65], and lower social support [65,69].

According to different studies [65,184,263], healthcare workers had the highest rate of poor sleep compared to other occupations [65,184,263]. They reported more difficulty in falling asleep [314], short sleep duration [314], and more sleep disturbance like insomnia [231,314].

Wellbeing, distress, fear and sleep levels during the pandemic were associated with age, gender, social condition, culture and comorbidity.

Age: Several studies have shown that being younger and having negative self-perceptions about ageing were associated with increased discomfort [5,75,309,319,359,363,364,406,407]. Thus, as a result, older people with positive self-perceptions of ageing seem to be more resistant during the COVID-19 outbreak [8,86,363,397]. In contrast with these findings, only Zhang and colleagues [365] argued that age was positively associated with psychological distress [365]. Nevertheless, an effect of the quarantine was found even on young people: children and adolescents in quarantine suffered greater psychological distress than children and adolescents not in quarantine [166]. Sleep disorders were more frequent in younger people [256,288,408]. In particular, as far as COVID-19 hospitalized patients are concerned, sleep disorders are greater in people aged 50 and over [223].

Gender: Several studies showed that being female was associated with higher levels of distress, and lower levels of psychological wellbeing [5,86,183,233,239,309,319,363,364,397,406,407,409,410]. Finally, fear of COVID-19 was more severe in females than in males [411]. Most of the papers found the prevalence of sleep disorders as insomnia [225,408] or poor sleep quality was higher among women [256]. Only Zhpu and colleagues [263] found conflicting results: in their paper, the sleep quality of men was worse than that of women [263].

Social Condition: People who were unemployed [309,407,409] or who had just lost their job reported higher psychological distress levels [406]. As for the workers, faculty, post-doctoral researchers and students showed lower levels of wellbeing than staff members [233,345]. Another significant association was found with marital status: those who were married had higher levels of wellbeing than those who were divorced because they had more social contacts and social support [318]. A relationship emerged between job loss, being single, and sleep disorders [69,256]. In particular, unemployed mothers or mothers who continued to work outside were more likely to suffer from sleep disorders than those who continued working at home or stopped working during lockdown [405].

Culture: Only one paper investigated cultural differences. According to Kimhi and colleagues [355], Arab respondents expressed a significantly higher level of COVID-19 distress compared with Jewish ones, who, on the contrary, reported higher levels of well-being and resilience [355].

Comorbidity: Having a background illness [239,310,324,398], depression [214,350], anxiety [214,329,350,412], stress [214], burnout [397], sleep problems [397], alcohol abuse [350], and OCD [38] were found to increase psychological distress. For what concerns fear, this was significantly related to depression [133,327], anxiety [133,234,327], specific phobias [327], stress [133,277], health anxiety [228], and general poor mental health [212]. PTSD [283,314], anxiety [70,188,223,256,269,271,272,408], physical dysfunctions [223], stress [70,256,269,271,369], depression [256,269,271], and general mental illness [69] were associated with sleep problems.

Table 21 shows information about the papers analyzed for the study of Wellbeing, Psychological Distress, Fear of COVID-19 and Sleep.

Table 21.

Other consequences of COVID-19. Summary of sources, with the number of papers analyzed, the total sample size, the provenance of the sample and the mediator variables. “MTurk” is used to indicate a sample extended worldwide.

12. Discussion

This review aimed to explore the impact of the first wave of COVID-19 on people, analyzing different psychological and psychosocial dimensions. To identify the domains impacted by COVID-19 we relied on previous pandemic literature (e.g., Ebola, SARS, MERS, Novel influenza A, Equine influenza), and chose to reanalyze them in the current one. The analysis of the results revealed that the dimensions most impacted by COVID-19 among psychosocial variables were: beliefs about COVID-19, coping strategies, risk perception, social support, and compliance and social distancing.

In particular, regarding the three fundamental moderators about beliefs and media persuasion (attitudes, knowledge, and finding news on social networks) the analysis of works showed that, although some attitudes were optimistic (e.g., the probability of being infected was perceived as low), most participants took precautionary measures to prevent infection [34]. On the contrary, higher levels of negative thoughts (e.g., fatalism toward the pandemic) were associated with lower behavioral intentions to comply with protective measures [36]. Furthermore, accurate knowledge about COVID-19 predicted more information-seeking behaviour, the ability to discern between true and false information, compliance with preventive measures, and showed lower panic reactions, a lower level of anxiety, and greater risk perception [25,41,126]. The major sources people used to seek information during the pandemic were TV and social media, but these also led to an increase in disinformation and a spread of fake news and conspiracy theories [16,17,43]. Regarding conspiracy theories about COVID-19, some studies showed that subjects who believed in them complied less with the suggested protective behaviours and were less likely to get vaccinated [18,51,52]. On the contrary, those whose core beliefs (beliefs that guide individuals in their identity) were less influenced by the pandemic reported to engage more in social isolation measures [38].

Beliefs about COVID-19, its transmission, and its protective measures, demonstrated to strongly influence compliance with them. In particular, low compliance was associated with belief in conspiracy theories, impulsivity, and self-centered behaviour [48,49]; instead, higher compliance with protective measures was associated with fear of COVID-19, trust in government and science, and higher risk perception [134,154,169,179].

The risk perception has shown a double effect: on the one hand, a higher risk perception induces higher levels of compliance, for example, in terms of compliance with social distancing [56]. On the other hand, however, it can lead to avoidant behaviors, such as being reluctant to seek medical assistance for fear of transmission, which can damage both the health of the individual and make the management of the pandemic more difficult, probably due to the sense of loss of control that is notoriously associated with high levels of risk perception [100,185].

Quarantine, and the COVID-19 pandemic in general, also had negative social consequences. For example, many social support networks have been interrupted: indeed, social distancing led to boredom, loneliness, social isolation fatigue, anxiety, and depression [54,135,159]. Nevertheless, social support proved to be crucial and had a positive impact on coping with the COVID-19 pandemic [56,59,66]. The results showed that positive coping strategies were correlated with less distress, fear, and general vulnerability, and higher wellbeing. In contrast, negative coping strategies (e.g., substance use, behavioral disengagement) were related to higher stress, distress, fear, and anger [77,79,88].

In addition, psychological dimensions regarding some areas of mental health, specifically anxiety, stress, depression, wellbeing, and sleep, were impacted due to the pandemic.

Restrictive measures had, in general, a protective effect on anxiety, whereas being more in contact with the virus resulted in higher levels of it. In particular, anxiety was negatively related to protective measures from COVID-19 [23,73,168], whereas it related positively to testing positive for COVID-19, being in an environment exposed to COVID-19 [58,110,219], knowing people who were COVID-19 positive [201,221,222], and having more knowledge about COVID-19 [16,23,41].

The COVID-19 pandemic was also associated with higher levels of depression, both in people with a history of psychiatric disorders and in others [78,326]. These results seemed to be due to quarantine and social isolation, but also to the constant exposure to information about COVID-19 [187,223,251].

Stress appeared to be positively related to the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent lockdown period [7,78,307]. This effect is buffered by some protective factors, such as lower exposure to COVID-19 [233,273] and some personality traits, such as emotional stability and conscientiousness [74].

The research has highlighted some risk and protection factors of wellbeing during the pandemic. Quarantine, living in areas with high virus prevalence, overexposure to COVID-19 information, and conspiracy theories seem to decrease wellbeing; while exercise, positive coping strategies, and greater social support seem to promote it [8,399].

The pandemic also impacted the distress experienced by people, particularly of those who were already physically and/or mentally ill. Indeed, poor sleep quality was positively correlated with stressful situations caused by the COVID-19 pandemic [69,273,369].

Overall, the COVID-19 experience may be useful to derive some evidence-based insights to be applied in case of future similar emergencies. Concerning compliance, promoting a correct risk perception in the population by disseminating correct information [17,19,20,39,46,169], and suggesting effective (and positive) coping strategies [71,77,87,91,93,94], would be helpful in increasing the degree of compliance with governmental measures [39,48,76,95,102,104,105,120,123,127,134,137,139,142,148,152,169,178]. Nonetheless, compliance is also affected by the perception of the effectiveness of such restrictions. For this reason, a better media campaign, focused not on fear but on efficiency (and self-efficacy), would be ideal, in the event that an extreme situation, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, should recur [21,24,40,41,46,49,169].

As highlighted by the literature, different management of the emergency would have also led to better psychosocial and psychological outcomes. In this regard, social support appeared to ease emergency management [55,66,67,69,70,71]. Greater social support was also useful in reducing the levels of anxiety, depression, stress, that ultimately contributed to people’s compliance with the rules, fear of contagion, and management of the emergency (both collectively and individually) [55,67,70,71]. Given the widespread increase in psychological/psychiatric symptoms (anxiety, depression, stress, insomnia, and psychological distress) [4,58,64,96,225,233,243,271,319,347], countries all over the world, especially those most affected by the virus, should envisage in such situations a prompter professional support to citizens, so to prevent the emerging or worsening of symptoms.

Finally, one of the factors identified in the scientific literature as key to countering the pandemic was resilience. Resilience resulted in stress [259,311], anxiety [24,57,133], and depression [157] protective factors, and has a positive relationship with wellbeing [329]. Resilience is fundamental in enabling people to change their behaviour in response to stressful events, like the COVID-19 pandemic, which in this specific case may prevent someone from getting sick or dying. For this reason, resilience appears to promote readiness to change, which is one of the factors that enable communities to respond adequately to emergencies such as a pandemic [12,13,14].

As described above, the pandemic affected several psychological dimensions. However, its effect appeared to be conditioned by a few factors that allowed us to qualitatively describe the psychological and socio-demographic profile of the most resilient people. The factors that more frequently had a significant influence on the previously analyzed variables are: age, gender, culture, social condition, healthcare workers and workload.

As for age, younger people appeared to be less resilient: they were more affected in terms of both psychosocial variables and mental health. Young people showed greater compliance with preventive measures, probably due to their greater risk perception and knowledge of the virus. Despite their major levels of compliance, young people suffered more from the effects of quarantine, implemented negative coping strategies more often, and suffered more from psychological distress and, in general, mental health problems (i.e., anxiety, depression, stress) [24,40,73,74,143,154,157,166,347].

Similarly, women were most affected by the pandemic: they tended to comply more with the rules because they were more worried and perceived greater risks, so they mainly used emotionally focused coping strategies. Again, despite showing higher compliance levels, women were more susceptible to anxiety, depression, stress, sleep disorders, and distress than men [89,114,139,187,223,363,408]. Furthermore, post-partum depression increased during the pandemic [266,348,349]. In light of this, young women appear to be the least resilient, especially under certain conditions such as postpartum.

An effect of culture was particularly evident on beliefs: collectivist societies seemed to have more accurate beliefs about COVID-19 than individualist societies [47,49]. However, the levels of risk perception, as well as people’s mental health, apart from possible cultural factors, appeared to be affected by the levels of contagion around the world. So, it was not possible to distinguish between the two causes which one influences more the results [78,127].

Lower levels of education were associated with more fear of dying by COVID-19, perception of susceptibility to the infection and worse overall knowledge about the pandemic [47], more anxiety [247], stress [258] and depression [347].

Lower income and unemployment were associated with higher levels of anxiety [247], stress [56], depression [347], higher levels of distress [406] and more sleep disorders [69,256]. The results about compliance and social distancing were conflicting regarding income [40,101,141,149].

Finally, healthcare workers experienced an increase in workload that led to several consequences, including higher risk perception [127], higher levels of anxiety [184], stress [288], depression [222], less wellbeing [232], worse sleep quality [184], and higher risk of psychological distress [357]. Healthcare workers implemented coping strategies like religious strategies, acceptance, planning, physical activity, virtual support groups, talk therapy, and positive framing [8,87,90]. Of these factors, some (e.g., age, gender) are known to be relevant to mental health even before the pandemic; nevertheless, the papers we analyzed did not distinguish the effects of these variables before and after the pandemic.

In conclusion, the aim of the paper was to research how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the psychological health of the global population during the first wave. In particular, we investigated which psychosocial and psychological variables were most affected, delineating a first and preliminary picture of symptoms related to COVID-19 that could be called “psychological COVID-19 syndrome”. This syndrome appeared to be characterized by an increase in stress, depression, anxiety, sleep disturbance, and distress related symptoms. Healthcare workers were the most affected by the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, as they found themselves on the front lines facing the virus and experienced a sudden increase in workload. In addition to healthcare workers, the results showed that people who proved less resilient were young women, with low income and low education, particularly if they were in post-partum condition. In light of this, it would be hopeful to implement prevention and aid projects for these individuals, particularly affected by the pandemic.

The number of studies about the psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic is increasing. However, the literature available until June 2020 was still in the early stages of maturity. Therefore, thanks to the articles published since June 2020, the “psychological COVID-19 syndrome”, hypothesized in this review through the first wave studies, could be modified or expanded. Future research should investigate the second and third waves of the pandemic so that comparisons can be made with the present research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G. and M.D.; methodology, A.G. and M.D.; investigation, V.F., C.P. and C.S.; data curation, V.F., C.P. and C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, V.F., C.P. and C.S. and M.D.; writing—review and editing, V.F., C.P., C.S., M.D. and A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Search Strategy: PsycInfo, PsycArticles, PubMed, Science Direct, PsyArXiv, NCBI, medRxiv, and Elsevier repository.

Searched Terms:

COVID-19 AND Psychological (Search results: 1010)

COVID-19 AND Psychology (Search results: 2160)

COVID-19 AND Risk perception (Search results: 116)

COVID-19 AND Coping strategy (Search results: 17)

COVID-19 AND Coping strategies (Search results: 91)

COVID-19 AND Personality (Search results: 314)

COVID-19 AND Personality Traits (Search results: 177)

COVID-19 AND Risk Perception (Search results: 116)

COVID-19 AND Fear (Search results: 300)

COVID-19 AND Anxiety (Search results: 626)

COVID-19 AND Psychology learning (Search results: 87)

COVID-19 AND Psychology resilience (Search results: 129)

COVID-19 AND Psychology self-efficacy (Search results: 15)

COVID-19 AND Psychology motivation (Search results: 39)

COVID-19 AND Psychology self-esteem (Search results: 15)

COVID-19 AND Psychology communication (Search results: 124)

COVID-19 AND Psychology control (Search results: 264)

COVID-19 AND Psychology optimism (Search results: 21)

COVID-19 AND Psychology workplace (Search results: 31)

COVID-19 AND Psychology Psychological (Search results: 365)

COVID-19 AND Psychology employee (Search results: 337)

COVID-19 AND Psychology sleep (Search results: 106)

COVID-19 AND Psychology depression (Search results: 84)

COVID-19 AND Psychology mental health (Search results: 798)

COVID-19 AND Psychology panic (Search results: 98)

COVID-19 AND Social distancing

COVID-19 AND Messages

COVID-19 AND Media

Table A1.

Main characteristics of the studies reviewed: reference, country, sample size, impacted dimension, and main findings (n = 294). Main characteristics of the studies reviewed.

Table A1.

Main characteristics of the studies reviewed: reference, country, sample size, impacted dimension, and main findings (n = 294). Main characteristics of the studies reviewed.

| Ref | Country | Sample Size | Impacted Dimension | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [136] | Germany | 419 | Compliance | People use protective measures primarily to protect themselves and only secondarily to protect others. Social distancing and washing hands are the most implemented. |

| [135] | USA | 895 | Compliance | Those with higher levels of boredom perceived social distancing as more difficult and adhered less. |

| [158] | Ireland | 500 | Compliance | Evidence to support communications that inform people about recommended behaviors. |

| [19] | USA | 1022 | Beliefs/ | Up-to-date and accurate specific health information Media Persuasion and special precautionary measures have been associated with a lower psychological impact. |

| [178] | MTurk | 324 | Compliance | “COVID-19 fear” is a predictor of a positive change in behavior (social distancing, better hand hygiene). |

| [67] | China | 144 | Anxiety, Depression, | Presence of depressive and anxiety symptoms Social Support in patients with COVID-19. Lower perceived social support appears to be related to an increase of the symptoms. |

| [137] | Brazil, Colombia, | 2285 | Compliance | Preventive measures are perceived as Germany, Israel, more effective when control levels are Norway, USA higher and the perceived risk is lower. |

| [21] | MTurk | 2176 | Beliefs/ | self-interested framing isn’t more Media Persuasion effective than prosocial framing. |

| [105] | USA | 1591 | Risk | Subjects demonstrated a growing awareness Perception of the risk and reported engaging in protective behaviors with increasing frequency. |

| [76] | China | 4607 | Risk | People with low self-control are more Perception vulnerable and more in need of psychological help to maintain mental health. |

| [34] | China | 6910 | Beliefs/ | Although attitudes towards COVID-19 were optimistic, Media Persuasion most residents took precautions to prevent infection. |

| [134] | MTurk | 525 | Compliance | Those who perceive COVID-19 as a serious threat and those who have greater faith in science are more likely to act in accordance with guidelines. |

| [145] | Italy | 894 | Compliance | Respondents were more likely to reduce their self-isolation if the quarantine extension turned out to be longer than they expected. |

| [282] | China | 2091 | Stress | The prevalence of post-traumatic stress symptoms in China one month after the outbreak was 4.6%. |

| [43] | Poland, UK | 652 | Beliefs/ | The prejudice towards foreign nationalities was Media Persuasion sensitive to the epidemiological situation. |

| [155] | China | 4607 | Compliance | Emotional and behavioral reactions were slightly influenced by the outbreak of COVID-19. |

| [163] | Germany, | 2192 | Compliance | Inducing empathy for those most vulnerable to the virus UK, USA promotes motivation to adhere to social distancing. |

| [304] | China | 52,730 | Other Consequences | Over time, levels of distress have significantly decreased. It can be partly attributed to the effective prevention and control measures taken by the Chinese government. |

| [42] | USA | 1709 | Beliefs/ | Those who are least likely to rely on their Media Persuasion intuitions and who have lower basic scientific knowledge were the worst at discerning fake news. |

| [367] | Holland | 439 | Other Consequences | Four predictors of "COVID-19 fear" were found: intolerance to uncertainty, health anxiety, increased media exposure, and risks to loved ones. |

| [130] | Italy | 1573 | Risk perception | In line with international literature, for the Italian population, too, experimental data confirmed a decrease in risk propensity of around 17.4% during the lockdown. |

Table A2.

Main characteristics of the studies reviewed, pt.2. Main characteristics of the studies reviewed.

Table A2.

Main characteristics of the studies reviewed, pt.2. Main characteristics of the studies reviewed.

| Ref | Country | Sample Size | Impacted Dimension | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [254] | China | 600 | Anxiety, | There were anxiety in 6.33% and Depression depression in 17.17% of the sample. |

| [231] | Nigeria | 884 | Anxiety, Stress, | Results revealed significant difference in Depression, the prevalence of depressive symptoms, insomnia symptoms, Other consequences post-traumatic stress symptoms and clinical anxiety symptoms with a higher prevalence reported by the healthcare personnel. |

| [65] | China | 7071 | Anxiety, Depression, | Doctors and nurses had more psychological Other Consequences, symptoms while defending against Social Support the outbreak than before. |

| [10] | China | 1315 | Anxiety, Depression, | A total of 1315 frontline HCWs were included, of which 49.1% Stress reported a moderate to severe stress 10.7% reported moderate anxiety to severe and 12.4% reported a major depression. |

| [92] | China | 30,077 | Beliefs/Media | The COVID-19 outbreak improves Chinese people’s Persuasion, Coping, ability to see the meaning of negative experiences. Risk Perception |

| [310] | Australia | 5071 | Stress, Depression, | More than three quarters of participants reported that Other consequences their mental health had been worse since the outbreak. A small proportion reported improvements in their mental health since the outbreak |

| [167] | UK | 520 | Compliance | There are significant associations between analytical thinking and compliance. Those who use slow cognitive styles are more likely to maintain social distance and reject COVID-19 conspiracy theories. |

| [144] | USA | 501 | Compliance | Greater conscientiousness was directly associated with adherence to guidelines, indirectly associated with greater self-efficacy. |

| [217] | China | 150 | Anxiety, Depression | The participants had severe anxiety and depression. |

| [267] | Turkey | 260 | Anxiety, Depression | the COVID-19 exerted statistically significant effects on psychology, social isolation, and BDI and BAI scores. |

| [224] | China | 992 | Anxiety | A clinical significance of anxiety symptoms was observed in 9.58% of the respondents. |

| [140] | Denmark | 799 | Compliance | People’s age (positively), levels of emotionality (positively), and the dark personality D factor (negatively) explain who is most willing to accept restrictions. |

| [142] | Switzerland | 705 | Compliance | The governmental rules were more effective and stronger among the older respondents, while having a lower risk perception. |

| [406] | Australia | 551 | Other consequences | 31% reported severe psychological distress, 35% in those with job loss and 28% in those still employed but working less. Those who had significantly greater odds of high psychological distress were younger, female, had lost their job and had lower social interactions. |

| [162] | USA | 789 | Compliance | Most teens reported not engaging in pure social distancing (70%), but were monitoring the news (75%) and performing disinfectant behavior(88%) |

| [56] | USA | 500 | Depression, Anxiety, | Findings highlight the importance of social connection to Other consequences mitigate negative psychological consequences. |

| [219] | China | 882 | Anxiety, Depression | The overall prevalence of GAD and depressive symptoms were 33.73%, and 29.35%, respectively. |

| [153] | USA | // | Compliance | Quarantine rules resulted in a significant flattening of the curve for Google searches for suicidal ideation, anxiety, negative thoughts and sleep disturbances. |

| [247] | India | 873 | Anxiety, Depression, | The prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress Stress were 18.56%, 25.66%, and 21.99%. |

| [258] | Brazil | 1460 | Anxiety, Depression, | Levels of stress, depression and anxiety were all Stress predicted by gender, food quality, psychotherapy frequency, exercise frequency, work outside, education level and age. |

| [18] | MTurk | 220 | Beliefs/ | Participants who believed that COVID-19 was a hoax or a Media Persuasion bio-weapon indicated less compliance with restrictive behaviors and greater commitment to self-centered preparedness behavior. |

Table A3.

Main characteristics of the studies reviewed, pt.3. Main characteristics of the studies reviewed.

Table A3.

Main characteristics of the studies reviewed, pt.3. Main characteristics of the studies reviewed.

| Ref | Country | Sample Size | Impacted Dimension | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [369] | China | 26 | Stress, | ISI was positively correlated with total sleep time, Other Consequences and negatively correlated with deep sleep; patient SRQ scores were positively correlated with TST, sleep efficiency and REM. SRQ-20 and sex were risk factors for insomnia. |

| [171] | USA | 503 | Compliance | Agreeableness and conscientiousness predicted endorsement of social distancing, hygiene, and the appeal of health messages in general. Dark traits (psychopathy, meanness, and disinhibition) predicted low endorsement of health behaviors. |

| [169] | MTurk | 1665 | Compliance, Beliefs/ | Some indication was found that concern about COVID-19 Media Persuasion and beliefs about others’ behavior may predict behavior change. |

| [73] | China | 1600 | Coping | The general population with a history of visits to Wuhan, those with a history of epidemics, ant those who perceived more severe impacts of the COVID-19 epidemic on their lives, emotional control, and epidemic-related dreams had a higher level of psychological distress than those with none or little of these experiences. During the C-19 outbreak, the degree of concern about media reports influenced the general population’s level of psychological distress and coping style. Media reports could influence the perception of the disease and the preventive measures implemented. |

| [139] | Norway | 8676 | Risk Perception | Increased media exposure, perception of measures as effective, and of the epidemic as a serious endeavor lead to positive predictions for health protection behavior. |

| [25] | Perù | 225 | Risk Perception | Knowledge is highly correlated with education, occupation, and age. |

| [221] | Spain | 3550 | Anxiety, | A substantial portion of the sample analyzed Depression, exhibited symptoms of depression, anxiety, Stress stress, and PTSD as measured on validated scales. In addition, respondents showed high levels of concern for their own health and that of relatives such as their parents, as well as for the social and economic situation resulting from the COVID-19 crisis. |

| [20] | USA | 955 | Beliefs/ | The effectiveness of the fear intervention was less Media Persuasion dependent on the strength of the emotional response than the prosocial intervention. In contrast, the prosocial message was more effective in increasing the willingness to self-isolate if it produced a strong, positive, emotional response. Both fearful and prosocial messages were equally effective in stimulating engagement in protective behavior. |

| [91] | China | 97 | Coping | Mindfulness reduced daily anxiety. The sleep duration of participants in this condition was less affected by increased infections in the community than participants in the control condition. |

| [22] | MTurk | 210 | Beliefs/ | Social distancing is significantly influenced by situational awareness. Media Persuasion Information sources, formal and informal were found to be significantly related to perceived understanding. |

| [248] | England | 2025 | Anxiety, | Higher levels of anxiety, depression, and trauma symptoms Depression, were reported, but not dramatically so. Anxiety Stress and depression symptoms were predicted by low income, loss of income, and preexisting health conditions. C-19-specific anxiety was greater in older participants. |

| [109] | Vietnam | 391 | Risk Perception | 11% of respondents did not actively search for information on C-19, while over 80% admitted to searching at least 2 times per day. |

Table A4.

Main characteristics of the studies reviewed, pt.4. Main characteristics of the studies reviewed.

Table A4.

Main characteristics of the studies reviewed, pt.4. Main characteristics of the studies reviewed.

| Ref | Country | Sample Size | Impacted Dimension | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [350] | China | 1074 | Anxiety, | A higher rate of anxiety, depression, hazardous Depression, and harmful alcohol use, and lower mental well-being Other Consequences in the Chinese population following the C-19 pandemic. The findings also revealed that young people are in a more vulnerable position in terms of mental health conditions and alcohol use. Young people are at higher risk for stress (despite lower mortality) as they take information from social media. |

| [58] | China | 7143 | Anxiety | 0.9% of respondents had severe anxiety, 2.7% moderate anxiety, and 21.3% mild anxiety. Living in urban areas, family income stability, and living with parents were protective factors against anxiety. Having relatives or acquaintances infected with COVID-19 was a risk factor for increased anxiety. Economic effects and effects on daily life, as well as delays in academic activities, were positively associated with anxiety symptoms, whereas social support was negatively correlated with anxiety level. |

| [109] | Vietnam | 391 | Risk Perception | 11% of respondents did not actively search for information on COVID-19, while over 80% admitted to searching at least 2 times per day. |

| [359] | Spain | 584 | Other consequences | Participants reported an important increase in negative affect and an important decrease in positive affect during the lockdown period, compared to before the lockdown. |

| [24] | China | 10,905 | Beliefs/Media Persuasion | In general, 74.1% of participants acknowledged the effectiveness of overall control measures and it was negatively correlated with regional number of existing cases. |

| [246] | China | 194 | Anxiety, | The overall prevalence of depressive symptoms, Depression, generalized anxiety and somatic symptoms were Stress 37.6%, 32.5% and 50%, respectively. |

| [147] | China | 1920 | Compliance | All studies together confirms that intentions to wear a face covering are higher in the priming reason condition compared to the priming emotion condition. |

| [280] | Italy | 2286 | Stress | Significant correlations were found among COVID-19-PTSD scores, general distress and sleep disturbance. |

| [44] | USA | 1034 | Other Consequences | Self-reported emotions showed that women were more worried, anxious, scared, and sad than men, and these results were supported by language differences. In addition, models showed that men wrote more frequently about concerns related to their health than women. |

| [164] | China | 1011 | Anxiety | The prevalence of moderate to severe anxiety was 4–5 times its normal level in urban China. The majority engaged in all six behaviors. Confusion about the reliability of information significantly fueled public anxiety levels. |

| [120] | Vietnam | 345 | Risk Perception | Those who use medical masks have a higher perception of risk than other people. This implies that people chose to wear a medical mask before the pandemic broke out perceive a higher risk than their counterpart. People tend to perceive greater risk as they age. |

| [47] | China | 1075 | Beliefs/ | The majority of respondents appear to take the risk of C-19 Media Persuasion (on themselves, their community, and their livelihood) very seriously and are aware of ways to reduce risk. Education was an important demographic determinant, and the impact of age is likely associated with both education and life experience. |