Making Visible Leadership Characteristics and Actions in Fostering Collective Teacher Efficacy: A Cross-Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

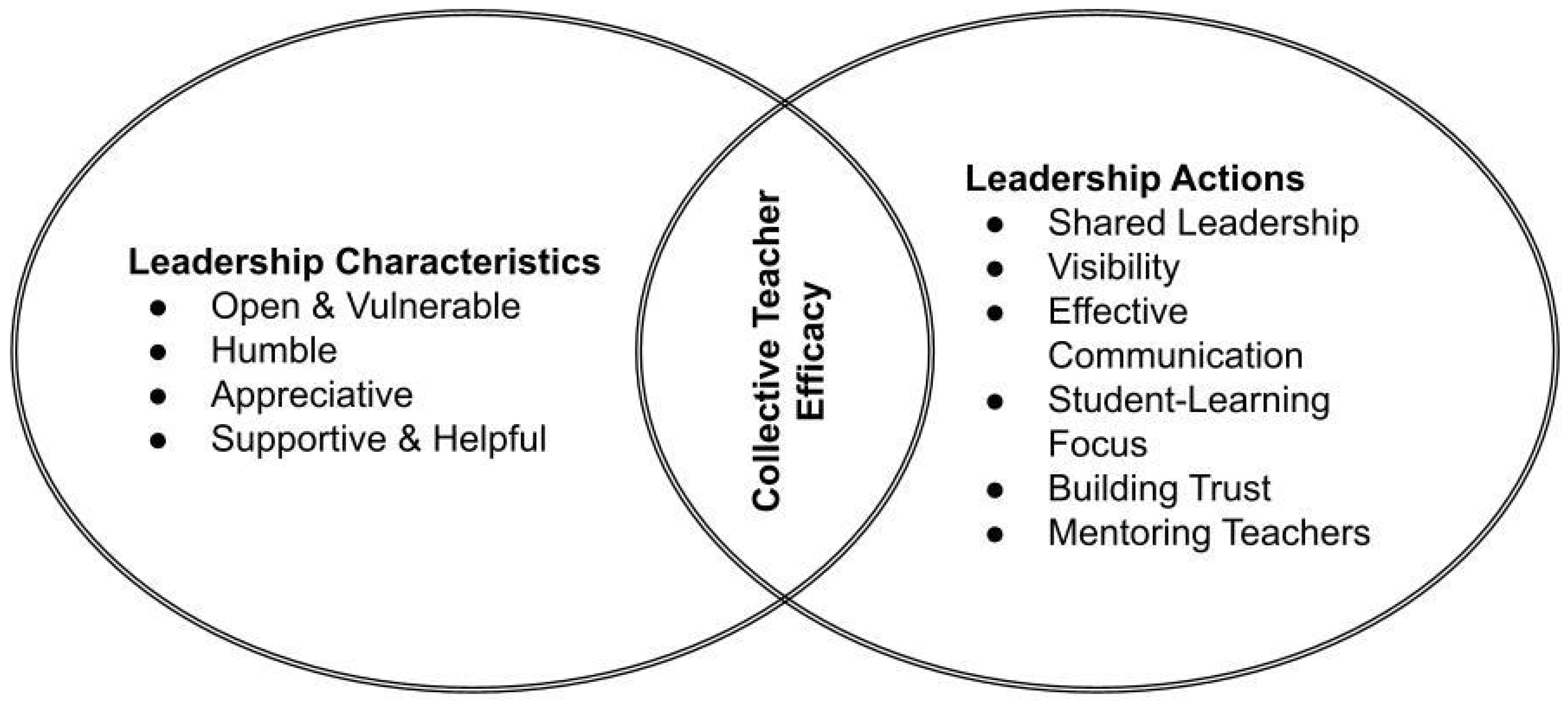

2. Purpose of the Study and Research Questions

- What are the leadership characteristics of school principals in high-achieving Title I schools for developing and nurturing CTE?

- What are the leadership actions at high-achieving Title I schools for developing and nurturing CTE?

3. Review of the Literature

3.1. Collective Teacher Efficacy

School Leadership and CTE

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Participants

4.1.1. Case 1: Patzun Elementary School Participants

4.1.2. Case 2: Escuintla Elementary School Participants

4.2. Materials

4.2.1. CTE Scale

4.2.2. Principal Semi-Structured Interview Protocol

4.2.3. Teacher Semi-Structured Focus Group Protocol

4.3. Procedures

4.4. Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Sociocultural Element: Leadership Characteristics

5.1.1. Characteristic: Being Open and Vulnerable

When your leaders and your mentors are honest, vulnerable and open, and they share their concerns with you, it [produces] this umbrella effect, an overarching effect that if they’re going to be open with you, you feel safe to be open with them. And I think that [creates] a culture of mutual respect. And we’re all in this together…we’re all trying to meet the same goals. It helps us to just follow [our] leader.

We don’t ever like to propose things and then not do it ourselves…I [model] a mindfulness lesson for about five minutes in faculty meetings with the teachers because it’s not fair that I’m preaching it and then not practicing it.

Vulnerability, trust, being honest and open, I think these are critical pieces to our sustainability…I was on a teaching team that had these four things and we were able to talk honestly about data and truly converse about improving student outcomes because we were not so busy hiding behind the data…I feel that’s been the heart of [our success]. It’s the coaching model and the data-focused culture that has created a safe space where we’re focused on being better educators to support our kids. We’re not hiding…we’re not [avoiding] talking about data.

5.1.2. Characteristic: Being Humble

I didn’t go into this position because I love power. That’s not my personality… It’s not really important for me to have the power, or have the final say. I think it’s important to get opinions from everyone and have that discussion. [I look for] a team effort in making decisions and talking out ideas.

5.1.3. Characteristic: Being Appreciative

5.1.4. Characteristic: Being Supportive & Helpful

Monday through Thursday from 10:00–10:30, I tradeoff between second or third grade…We do Read Naturally with kids for that half hour of time…Then I go in the lunchroom. I help with lunch. Most days I end up on the playground helping with recess duty because then there’s two eyes on the playground instead of one. Yesterday, I was the librarian. Our librarian was absent, so I went and read stories to our kindergarten and second grade.

It really helps for your administration to be positive and more of a support then a critical person…When I was so lucky to get a job here, I immediately felt comfortable. Everybody made me feel really welcome. A big part of that was our principal…We know she has our backs. She’s in our corner. We know that 100%.

5.2. Sociocultural Element: Leadership Actions

5.2.1. Action: Shared Leadership

We have committee meetings where teachers have an opportunity to develop leadership…and then individuals are able to facilitate those meetings…Everybody on the faculty…determines who will be representatives for each of these committees. I allow them to decide which [committee] is going to be of most benefit to them.

I’ve worked in a school before where it was…like a dictatorship…People are unhappy with decisions being made [with] no input from others…I remember at that point thinking, ‘This is kind of taking the joy away from the job’. And, so I’ve always tried to keep in mind the teachers’ perspective…So, a lot of times I ask for input when making decisions…If possible, I try to involve teachers, or aides, or whoever…I try and involve them in the decision-making process…I think you get a lot more buy-in when you have ownership from others.

5.2.2. Action: Leader Visibility in School and in Community

We do a lot of home visits. If we don’t see [students] in two days, you can pretty much expect me and our counselor to be knocking at [their] door and just checking up on [them]…We’re a neighborhood school so we usually just put on our coats and we’ll walk to the house…We do a lot of home visits for tardies and absences…We’ll say hey if you want, we can wait 10 to 15 min while you get [your child] ready and we’ll take them to school.

One thing I love about [our principal] is she always puts herself in the classroom…If we need a substitute teacher [she’s] in the classroom. If somebody’s gone…and we need someone to fill in she jumps in. She is constantly keeping herself in the classroom so she doesn’t forget what it’s like to be a classroom teacher. That makes a big difference for us as teachers knowing that she’s willing to do that.

- Escuintla’s principal added,

I went into education for the kids and that’s why I’m here. It’s not because I wanted to have a desk job and sit behind a computer…I try to keep relevant and keep connected to the kids and the staff.

- For Escuintla’s principal, being visible allows her to build relationships and to have an ongoing pulse of the school’s happenings.

5.2.3. Action: Effective Communication

Passing down the hall, or in the library [it’s easy to address student needs]…The library is where most of our teachers’ aides run groups. And so, you come in here and you can catch four to five different aides and have that conversation if needed.

5.2.4. Action: Student-Learning Focus

5.2.5. Action: Building Trust

When we’re doing what we’re supposed to do, you need the trust from the admin that we will do it. Admin will still check in with us. We’re still accountable. But, we’re not constantly looking over our shoulders wondering if [the principal] is going to attack us. That’s why I can go to [our principal] and ask him [anything] without fear of what’s going to happen to me. And that makes a better environment for everyone.

- The principal reiterated the importance of this trust when he said,

- The principal realized the importance of trusting his teachers and allowing them the freedom of making choices. This trust helped the teachers to gain confidence.

I feel like we can be vulnerable. I can share weaknesses or problems that I have without being nervous…The aide or somebody will walk in my classroom and I’ll say, ‘I could use some help with these manipulatives.’ I had an aide say, ‘Well, have you thought of this?’ I loved that she…would feel comfortable giving me advice…I feel [safe asking questions and getting advice] when it comes to our faculty meetings and we share successes and concerns…It’s so nice to be able to be vulnerable and ask for help without feeling belittled.

- Another teacher included the following regarding the safe trusting feelings that were had among staff member:

When we’re done [with interventions], I ask the aides, ‘How did that go?’ ‘Did you like [the intervention]?’ ‘Did the students like it?’…So, I just open up to them letting them know I care about what they think…We’re just being vulnerable with each other.

- These statements suggest that the teachers feel safe and trust being vulnerable with others through asking others’ opinions. At Escuintla trust is seen in valuing others’ abilities and skills, or simply by trusting others.

5.2.6. Action: Mentoring Teachers

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

7.1. Limitations

7.2. Educational Importance

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CTE | Collective teacher efficacy |

| FRL | Free and/or reduced lunch |

| SES | Socio-economic status |

References

- Ford, O.D.; Grace, R. The impact of poverty on student outcomes. Ala. J. Educ. Leadersh. 2017, 15, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- McFarland, J.; Hussar, B.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, K.; Hein, S.; Diliberti, M.; Forrest Cataldi, E.; Bullock Mann, F.; Barmer, A. The Condition of Education 2019; NCES 2019-144; National Center for Education Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, D.J. Double Jeopardy: How Third-Grade Reading Skills and Poverty Influence High School Graduation; Annie E. Casey Foundation: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, C.M.; Arnold, N.W. The Title I program: Fiscal issues and challenges. Int. J. Educ. Reform 2015, 24, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, R.D.; Hoy, W.K.; Hoy, A.W. Collective teacher efficacy: Its meaning, measures, and impact on student achievement. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2000, 37, 479–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. Collective teacher efficacy: An introduction to its theoretical constructs, impact and formation. Int. Dialogues Educ. 2019, 6, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, S.B.; Tisdell, E.J. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation, 4th ed.; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W. H. Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard, R.D.; Hoy, W.K.; Hoy, A.W. Collective efficacy beliefs: Theoretical developments, empirical evidence, and future directions. Educ. Res. 2004, 33, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M.; Barr, M. Fostering student learning: The relationship of collective teacher efficacy and student achievement. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2004, 3, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Thought and Language; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard, R.D.; Skrla, L. The influence of school social composition on teachers’ collective efficacy beliefs. Educ. Adm. Q. 2006, 42, 216–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, W.K.; Sweetland, S.R.; Smith, P.A. Toward an organizational model of achievement in high schools: The significance of collective efficacy. Educ. Adm. Q. 2002, 38, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calik, T.; Sezgin, F.; Kavgaci, H.; Kilinc, A.C. Examination of relationships between instructional leadership of school principals and self-efficacy of teachers and collective teacher efficacy. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2012, 12, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar]

- Cansoy, P. Transformational school leadership: Predictor of collective teacher efficacy. Sak. Univ. J. Educ. 2020, 10, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fancera, S.F.; Bliss, J.R. Instructional leadership influence on collective teacher efficacy to improve school achievement. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2011, 10, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, C. School principals’ transformational leadership styles and their effects on teachers’ self-efficacy. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2019, 7, 622–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Versland, T.M.; Erickson, J.L. Leading by example: A case study of the influence of principal self-efficacy on collective efficacy. Cogent Educ. 2017, 4, 1286765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, R.D. Collective efficacy: A neglected construct in the study of schools and student achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 93, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldridge, J.M.; Fraser, B.J. Teachers’ views of their school climate and its relationship with teacher self-efficacy and job satisfaction. Learn. Environ. Res. 2016, 19, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.A.; Hogaboam-Gray, A.; Gray, P. Prior student achievement, collaborative school processes, and collective teacher efficacy. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2004, 3, 163–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissom, J.A.; Egalite, A.J.; Lindsay, C.A. How Principals Affect Students and Schools: A Systematic Synthesis of Two Decades of Research; The Wallace Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nordick, S.; Putney, L.G.; Jones, S. The principal’s role in developing collective teacher efficacy: A cross-case study of facilitative leadership. J. Ethnogr. Qual. Res. 2019, 13, 248–260. [Google Scholar]

- Skaalvik, E.M.; Skaalvik, S. Dimensions of teacher self-efficacy and relations with strain factors, perceived collective teacher efficacy, and teacher burnout. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 99, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfi, B.; Gielen, S.; De Fraine, B.; Verschueren, K.; Meredith, C. School-based social capital: The missing link between schools’ socioeconomic composition and collective teacher efficacy. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 45, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moolenaar, N.M.; Sleegers, P.J.C.; Daly, A.J. Teaming up: Linking collaboration networks, collective efficacy, and student achievement. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2012, 28, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K.; Patten, S.; Jantzi, D. Testing a conception of how school leadership influences student learning. Educ. Adm. Q. 2010, 46, 671–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, R.D.; LoGerfo, L.; Hoy, W.K. High school accountability: The role of perceived collective efficacy. Educ. Policy 2004, 18, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balyer, A.; Ozcan, K. Cultural adaptation of headmasters’ transformational leadership scale and a study on teachers’ perceptions. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 2012, 49, 103–128. [Google Scholar]

- Spradley, J.P. The Ethnographic Interview; Waveland Press: Long Grove, IL, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy. In Encyclopedia of Human Behavior; Ramachandran, V.S., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994; Volume 4, pp. 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mendenhall, D.R.; Jones, S.H.; Putney, L.G. Making Visible Leadership Characteristics and Actions in Fostering Collective Teacher Efficacy: A Cross-Case Study. Merits 2025, 5, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits5020012

Mendenhall DR, Jones SH, Putney LG. Making Visible Leadership Characteristics and Actions in Fostering Collective Teacher Efficacy: A Cross-Case Study. Merits. 2025; 5(2):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits5020012

Chicago/Turabian StyleMendenhall, Donald R., Suzanne H. Jones, and LeAnn G. Putney. 2025. "Making Visible Leadership Characteristics and Actions in Fostering Collective Teacher Efficacy: A Cross-Case Study" Merits 5, no. 2: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits5020012

APA StyleMendenhall, D. R., Jones, S. H., & Putney, L. G. (2025). Making Visible Leadership Characteristics and Actions in Fostering Collective Teacher Efficacy: A Cross-Case Study. Merits, 5(2), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits5020012