Abstract

During the COVID-19 pandemic, lockdown and working from home (WFH) were two significant non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) deployed to stop the spread of the virus and also maintain economic activity. Lockdown caused significant socio-economic disruptions and varied in efficacy by location, even while it helped slow the spread of the virus and provided medical personnel with more time to respond to the crisis. WFH, however, was introduced to mitigate business collapse, and it presented crucial benefits such as flexibility and reduced commuting. However, it also presented major challenges, including work–life conflicts, productivity concerns, and mental health issues. By examining the short- and long-term effects of these NPIs on various sectors and demographics, this study assesses their efficacy in crisis management, and our results show that although WFH and lockdowns were essential for crisis management, their effectiveness varied depending on sectoral differences, timing, and implementation tactics. Furthermore, the ongoing shift towards hybrid work underscores the need for adaptive policies that balance productivity, mental well-being, and economic sustainability. Moreover, future research should focus on exploring the long-term implications of WFH and hybrid work models in order to ensure better preparedness for future crises and refine existing NPIs for more effective crisis management.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak of the 21st century emerged as an unprecedented global crisis. As with most large-scale crises, the implementation of established social measures, often framed within the scope of crisis management, became imperative to contain the spread of the virus. These measures are typically aimed at providing medical professionals sufficient time to develop effective remedies such as vaccines and therapeutic treatments. Commonly adopted social strategies in times of public health emergencies include school closures, curfews, movement restrictions, social distancing, and lockdowns. Collectively, these interventions are frequently categorized as non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs)—a classification that underscores their role in offering health authorities critical time to assess the severity, morbidity, and mortality associated with an outbreak [1]. NPIs also encompass the rapid identification and isolation of infected individuals, quarantine enforcement, and physical distancing protocols aimed at minimizing secondary transmissions. Historically, such approaches have proven effective in managing the spread of both endemic and pandemic diseases. In contrast, vaccines have generally not played a primary role in the initial management of pandemics and epidemics. This is largely due to the timeline of vaccine development and distribution in light of the fact that when they become publicly available, the crisis has often already become widespread or surpassed its initial wave [2].

As a global response, nearly all countries implemented lockdown as one of the most prominent measures to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, alongside other hygienic practices. While lockdowns did not immediately halt the transmission of the virus, given that infection rates remained high in some regions despite their enforcement, they nevertheless provided critical time for authorities and health professionals to develop additional responses and explore medical solutions [3]. In cases where lockdowns were perceived to have been ineffective, the issues often stemmed from poor timing or inadequate planning during implementation [3]. Furthermore, the effectiveness of lockdowns may have been compromised when applied in isolation, without being complemented by other preventative measures such as regular handwashing, minimizing physical contact (e.g., handshakes and hugs), and practicing social distancing.

Although widely regarded as effective during pandemics—particularly in the absence of pharmaceutical interventions—the prolonged implementation of lockdowns began to yield unintended or secondary consequences across societies. These adverse impacts spanned various sectors, including the global economy, food security, education, tourism, hospitality, sports, gender relations and domestic abuse, leisure, and mental health, among others [4]. These outcomes were not entirely unexpected, given the restrictions on individual movement, which in many cases required official approval for any form of travel. In terms of economic consequences, many businesses were unable to withstand the financial strain imposed by lockdowns and where feasible, resorted to adopting flexible work arrangements. This led to the emergence of working from home (WFH) as a critical component of the lockdown policy during the COVID-19 crisis. While WFH is fundamentally a work model, during the pandemic, it was deployed as a resilience strategy and designed to mitigate business collapse, ensure operational continuity, and preserve employment.

Despite the current context marked by the availability of vaccines and effective treatment options for COVID-19, it remains essential to evaluate the effectiveness and socio-economic impacts of lockdown and WFH as crisis management measures employed during the pandemic. This evaluation is crucial because lockdowns have historically been used in managing various health crises, including the 14th-century plague. When comparing these historical applications to their use during the COVID-19 outbreak, the differences in outcome are not particularly striking. Therefore, it is imperative to critically assess the design and timeliness of lockdown implementation, as well as to evaluate how it is combined with other public health measures such as physical distancing, widespread testing, and rigorous hygiene practices. The primary objective of such assessments is to optimize the efficacy of future crisis responses while minimizing adverse socio-economic consequences. This approach will be instrumental in enhancing preparedness for potential future disease outbreaks that may necessitate the use of lockdown as a crisis management strategy.

Although a considerable volume of literature exists on the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated concepts, the socio-economic impacts of the pandemic remain insufficiently explored [5]. In particular, the long-term societal effects of WFH on urban economies, organizational culture, and mental health have not been fully examined. There is also ongoing uncertainty surrounding the evolution of WFH and whether the currently popular hybrid work model can deliver sustainable socio-economic and public health benefits. The majority of existing studies tend to emphasize the public health implications of the pandemic, often overlooking its influence on firm management and organizational resilience [6]. Furthermore, WFH is predominantly treated as a mere work model in many studies, despite its profound implications during the pandemic. In contrast, this study conceptualizes WFH as a crisis management strategy rather than as simply a work model. It focuses on its integration with the lockdown policy and its associated impacts on mental health and overall well-being. To the best of our knowledge, the classification of WFH as a crisis management tool remains underexplored. This underscores the importance of understanding its role within organizational resilience strategies and broader crisis management frameworks. Moreover, while some research has addressed short-term adaptations to WFH, which include impacts on productivity, mental health, and economic indicators like GDP or employment, there is still limited focus on its long-term effectiveness across different sectors and demographic groups. Although certain studies have highlighted the security-related benefits of WFH during the pandemic [7], its broader effectiveness requires further investigation. Lastly, the long-term impacts of WFH, particularly under varying work conditions, remain significantly under-researched. With hybrid work models becoming increasingly common, there is a pressing need to examine how they may affect aspects such as productivity, mental health, social isolation, and work–life balance. A deeper understanding will enable employees to better manage expectations and help employers design more effective support systems. These insights are essential for the development of robust organizational policies and cultures that facilitate the successful implementation of both WFH and hybrid work arrangements.

The purpose of the current study, therefore, is to evaluate the socio-economic impacts of lockdown and WFH by examining both phenomena as crisis management and resilience measures adopted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Achieving this objective will aid in determining whether these strategies remain as effective as they were historically and whether they can be relied upon as efficient and sufficient tools for managing future crises. Additionally, this study seeks to identify both the short-term and potential long-term socio-economic impacts of WFH, particularly as hybrid working continues to be adopted across many organizations. By exploring sector-specific and demographic variations in these impacts, the study aims to contribute meaningful insights that can support better preparedness and response strategies for future crises. The evaluation is conducted from a conceptual standpoint, and the findings are intended to guide the development of policies that facilitate more effective implementation of WFH and lockdown measures as crisis management tools. Furthermore, the outcomes of this study will help highlight key areas where further empirical and longitudinal research is needed.

2. Background

2.1. The Concept of Crisis Management

Understanding the concept of crisis management is deeply rooted in an understanding of the concept of crisis itself. Since a crisis can be described from various perspectives, crisis management can likewise be explained from different angles, depending on the nature of the crisis in question. The absence of a universally accepted definition of crisis limits the development of crisis management as a theoretical field of study, despite the existence of several converging definitions found in the literature [8]. Crises have been described from a wide range of perspectives, depending on the academic field, discipline, or specific context. From the standpoint of public management, a crisis is defined as a situation that exceeds the capacity of existing structures and processes to manage and protect the public [9]. A notable example of this is the experience of the general public during the COVID-19 pandemic. From a corporate perspective, a crisis is often seen as an event that marks a turning point—one that can steer the organization either toward success or failure [10]. In organizational contexts, however, a situation is typically considered a crisis only when it generates significant controversy among stakeholders [11]. In addition to the multiple definitions of crisis, a variety of overlapping terms—such as catastrophe, disaster, emergency, incident, and event—further complicate efforts to establish a single, clear definition [9]. Despite this complexity, most definitions of crisis share at least three core characteristics: (1) a threat to existing goals and values, (2) a limited time frame for decision making, with high stakes, and (3) numerous unpredictable elements and uncertainties surrounding the situation [9].

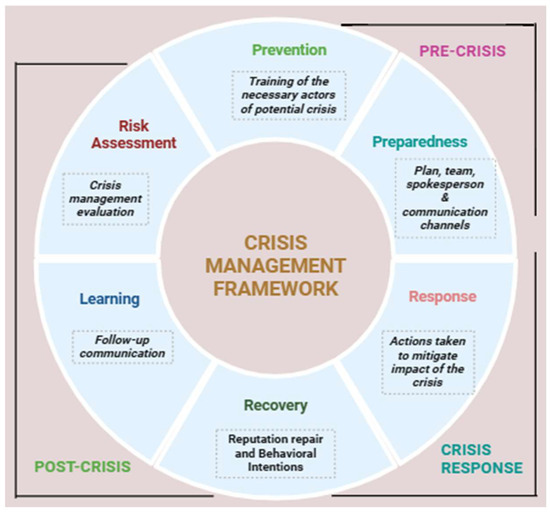

Building on the explanation of crisis provided above, it is important to understand that crisis management is a process designed to prevent or mitigate the damage a crisis can inflict on the public, a corporation, or an organization and its stakeholders [12]. It is better understood as an ongoing process rather than a singular event—hence, it is commonly divided into three main phases: pre-crisis, crisis response, and post-crisis. As illustrated in Figure 1 below, these three phases can be further broken down into individual components, collectively referred to as the crisis management cycle. The components of this cycle include, but are not limited to, prevention, preparedness, response, recovery, learning, and risk assessment [9]. The holistic integration of these phases and their components forms the conceptual framework of crisis management [12]. According to Pursiainen (2017), although a crisis itself may be temporary, crisis management is a continuous process that becomes a critical activity, even during periods between crises [9].

Figure 1.

Crisis management framework; adapted from Tony Jacques, 2007 [13].

2.2. Resilience Theory

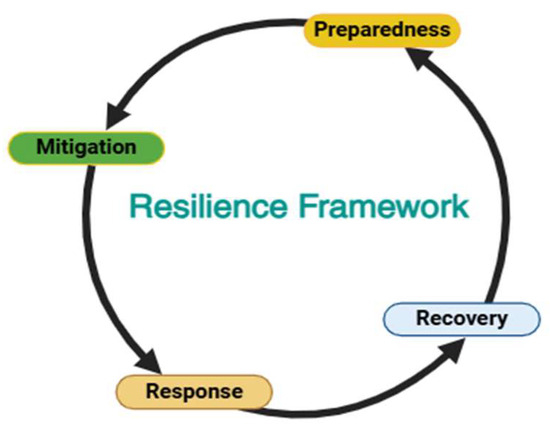

Resilience is another concept closely associated with crisis management. It is a psychological construct that has played a significant role in the study of risk management [14,15]. The definition and assessment of resilience are context-dependent and therefore, vary based on the specific object of analysis [14]. In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, resilience is most appropriately viewed through an economic lens, making economic resilience the central focus in this context. However, other forms of resilience—such as infrastructural, community, and disaster resilience—are also widely recognized [14]. Economic resilience refers to a community’s financial stability and capacity to recover, assessed using factors such as housing capital, income equality, employment rates, business size, and access to healthcare [16]. It is generally defined as the ability of a system to recover from a severe shock and includes both inherent and adaptive forms of resilience [17]. Like many resilience frameworks, economic resilience is composed of four key components: preparedness, mitigation, response, and recovery, as illustrated in Figure 2 below. Although the world was largely unprepared for the COVID-19 pandemic, the introduction of policies such as lockdowns and movement restrictions helped to mitigate the severity of its impact. These measures paved the way for response actions like WFH, which helped steer the global economy back toward recovery [18]. WFH became a crucial part of the resilience strategy during the pandemic [19,20]. This phenomenon exemplified the core elements of economic resilience. Had WFH not been implemented and the global workforce remained idle under lockdown while awaiting a cure, the world economy might have collapsed, with little prospect of recovery.

Figure 2.

Basic economic resilience cycle.

In addition, organizational resilience became highly relevant and clearly manifested during the pandemic. Once the economy is impacted, the effects inevitably cascade down to individual organizations. Organizational resilience, therefore, refers to the accumulated cultural capacity of an organization to understand risks and adverse events, absorb the resulting pressure, and ultimately protect its social capital and reputation [21,22]. Organizational resilience is built upon four key pillars: preparedness, responsiveness, adaptability, and learning, which are closely aligned with the economic resilience cycle illustrated in Figure 2. These pillars are further supported by foundational elements of cultural and social capital, such as trust and a strong sense of organizational identity. Together, these form the basis of organizational resilience [23]. During the lockdown period, many organizations were compelled to adopt alternative methods of supervision and management. Most notably, they had to place significant trust in their employees to perform effectively without direct physical oversight—an essential step to ensure business continuity. Furthermore, organizations began implementing intervention and support measures to assist employees in overcoming the challenges of working from home. These initiatives were critical to maintaining optimal performance and improving job satisfaction under the new working conditions.

2.3. Implementation of Lockdown and WFH as Crisis Management Measures During the COVID-19 Pandemic

When the crisis management cycle is applied to the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, lockdown emerges as one of the major actions taken in response to the crisis. It was implemented in various forms across different countries [24]. Many of these approaches have historical roots in medieval medicine and previous pandemics, and they have proven to be effective both in the past and during the COVID-19 era. One of the earliest strategies adopted during the initial wave of the coronavirus was the elimination strategy, notably employed by Taiwan and South Korea. These countries became role models for their ability to maintain social and economic activities even at the peak of the outbreak. Their success was largely attributed to proactive measures, including widespread testing, contact tracing, and the isolation of confirmed cases [25]. On the other hand, Australia and New Zealand implemented comprehensive lockdowns through strict border closures. Although these countries also achieved a significant level of success in managing the outbreak, it came at a higher socio-economic cost [26]. In contrast, most European countries, along with the World Health Organization (WHO), adopted a “flattening the curve” approach. This strategy aimed to slow the spread of the virus, minimize economic disruption, and prevent the collapse of healthcare systems [27]. Countries such as Brazil and the United States, which downplayed the severity of the virus and failed to implement coordinated national responses, experienced higher mortality and morbidity rates—outcomes that could potentially have been avoided with more centralized action [28,29]. In addition to lockdowns, many governments enforced complementary measures such as rapid case identification, quarantine protocols, and physical distancing. These were key components of lockdown policies aimed at preventing secondary transmission within the general population [1].

Most of the measures adopted during the coronavirus outbreak can be said to have bypassed the pre-crisis phase of the crisis management framework, aligning more closely with the crisis response phase. Comprehensive lockdowns, for instance, were clearly response measures, as were many other interventions implemented at the time. This is largely because crises of such high magnitude are often unforeseen and therefore, not adequately anticipated—making it difficult to begin the management cycle with the pre-crisis phase. However, in the case of a future recurrence, the post-crisis phase—characterized by learning and risk assessment—should inform improved prevention and preparedness strategies during the pre-crisis phase. Thus, lockdowns clearly fall under the crisis response phase of the crisis management framework. Similarly, within the resilience cycle, lockdowns can be considered response measures, as they were adopted in reaction to the sudden emergence of the pandemic. At that point, there were few viable alternatives available.

However, comprehensive lockdowns could only be sustained for a limited period due to their significant impact on both society and the economy. For instance, many companies were forced to shut down during the prolonged global lockdown triggered by COVID-19. Additionally, public frustration grew over time, leading people to pressure authorities to ease the restrictions—either by lifting curfews or relaxing social distancing measures [30]. This situation created an urgent need for alternative crisis management strategies that could sustain business operations, even amid ongoing restrictions. Consequently, the widespread adoption of teleworking, or (WFH), became a vital response measure during the lockdown period.

Teleworking, although primarily recognized as a work model, was introduced as a follow-up measure to the lockdown. After all, no one knew when the coronavirus would come to an end, with some speculating that it might become a recurring issue, like the seasonal flu [30]. The introduction of teleworking during the lockdown served a dual purpose: it helped curb the spread of the virus while allowing socio-economic activities to continue or gradually resume under restricted conditions [27]. This solidifies teleworking’s role as a recovery measure within the post-crisis phase of the crisis management cycle, as well as within the recovery phase of the resilience cycle—demonstrating that it is more than just a work model. In both frameworks, teleworking can be viewed as a key recovery component, contributing to the revival of the broader situation. In fact, its adoption could be said to have revitalized the economy and saved numerous businesses that were on the brink of collapse. Although it was not introduced as a direct response to combat the outbreak, nor as a form of retaliation against the crisis, teleworking played a critical role in restoring the remaining fragments of the economy by enabling economic activities to resume and gradually return to stability.

As a resilience measure during the pandemic, teleworking can arguably be considered one of the most dramatic developments in labor history. It provided employees with greater control over when and how they worked, as well as more time to spend with their families [31]. This marked a significant shift from the pre-pandemic era, during which most organizations were reluctant to encourage teleworking, often viewing it as more detrimental than beneficial [32]. Another key reason for the previous lack of its widespread adoption was the absence of modern internet infrastructure and software tools. These technologies—now widely available—have greatly influenced the ability of organizations to swiftly adapt to new working patterns when the need arises [33]. Despite its rapid expansion during the pandemic, the concept of teleworking is not entirely new. Over the past decade, some companies had previously permitted a portion of their workforce to work from home [34]. For example, in EU countries, the percentage of people working remotely, either part- or full-time, had been steadily increasing, even before COVID-19—from 7.7% in 2008 to nearly 14% in 2017. This gradual growth reflects a slow but consistent trend toward teleworking prior to the pandemic [35].

Consequently, the availability of modern software, increased employee ICT awareness, and contemporary organizational practices have collectively enabled the implementation of teleworking, without the need for extensive technical customization [36]. This shift was not limited to private enterprises; government employees also adapted by integrating new digital tools into their workflows. As physical offices transitioned to virtual environments, many began conducting their work online, using digital tools for communication and collaboration in innovative ways [37]. Since the onset of the crisis, numerous reports have documented a significant increase in the adoption of teleworking, underscoring the crucial role of modern technology. In simple terms, modern technology and ICT form the foundation for teleworking, making them key elements of the preparedness phase within the resilience cycle for many organizations. For instance, in a 2020 study conducted by the International Labor Office (ILO), it was reported that approximately 60% of employees in Finland shifted to working from home. Over 50% of employees teleworked in Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Denmark, while around 40% did so in Ireland, Austria, Italy, and Sweden [38]. These transitions were made possible largely due to the pre-existing digital infrastructure in these countries, thus further illustrating the essential role of technology within the resilience framework of organizations seeking to adopt teleworking.

Aside from helping to prevent the further spread of the disease, teleworking—as part of the crisis management measures implemented during the lockdown—also brought several organizational benefits. These include increased flexibility in terms of time and location, greater professional autonomy, improved work–life balance, and reduced commuting time [39]. A 2020 report by the International Labor Organization (ILO) further emphasized that teleworking played a crucial role in ensuring business continuity during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Key benefits noted include reduced travel time, fewer workplace distractions, and enhanced work–life balance, all of which contributed to improved productivity and job satisfaction [38]. In addition to these advantages, teleworking also introduced unique social benefits. Notably, it improved employment prospects for minority and underrepresented demographics—such as individuals living with disabilities, elderly employees, women with caregiving responsibilities, and people residing in rural or remote areas—more than ever before due to the widespread shift toward remote work [39]. Moreover, evidence shows a significant rise in the number of women, particularly those with childcare responsibilities, pursuing higher-paying and senior-level careers since the adoption of teleworking. These women have demonstrated a stronger inclination toward remote work compared to that of the broader workforce, as it allows them to manage both professional and family responsibilities simultaneously [40]. Historically, this was not the case. Many women had to forgo promising career opportunities due to the disproportionate burden of childcare and domestic duties [41]. Some even had to reduce their working hours or take extended leave following childbirth, which hindered their long-term career progression [42].

Nevertheless, the impacts of teleworking as a crisis management tool during the COVID-19 pandemic remain a controversial topic among renowned scholars and scientists, despite its clear usefulness in maintaining business operations and social interactions in many workplaces during lockdown [43]. One ongoing debate concerns whether or not working from home may lead to decreased productivity, particularly due to increased instances of illness and presenteeism—where employees work while unwell, often less effectively [44]. Another concern is the potential hindrance to innovation. For example, video conferencing has been criticized for limiting full human interaction, as it restricts non-verbal cues such as body posture, hand gestures, and facial expressions. This lack of physical presence can impair engagement and reduce the ability of participants to contribute at their full potential [45]. Teleworking has also been associated with several challenges, including work–family conflict, overworking, loneliness, and ambiguity, which can negatively impact employees’ mental well-being [46]. The constant presence of family members, particularly children, can significantly disrupt work focus, further affecting productivity [47,48]. In terms of health, both physical and mental issues have been widely reported. Many teleworkers have experienced an increase in musculoskeletal problems, especially upper limb disorders, often caused by poorly arranged workstations and extended periods of sitting in uncomfortable positions [49]. On the mental health front, employees have reported various issues arising from the blurred boundaries between their private space, social life, and work environment—creating an uncertain and unpredictable dynamic [50]. Experimental findings further suggest that remote work can lead to difficulties such as work–home conflict, procrastination, communication breakdowns, boredom, and feelings of isolation [51]. A remote work survey conducted in 2021 revealed that many employees struggled to disconnect from work after hours, with a significant number citing loneliness as their greatest challenge [52]. Despite these criticisms and concerns (including increased job intensity, longer working hours, and evidence of unpaid labor), teleworking is still widely regarded as an effective and necessary intervention during the pandemic [39]. Its ability to sustain economic and social activities during a global crisis underscores its value, even as debates about its long-term implications continue.

3. Socio-Economic Impacts of Lockdown and WFH

3.1. Short- and Long-Term Impacts of Lockdown and WFH

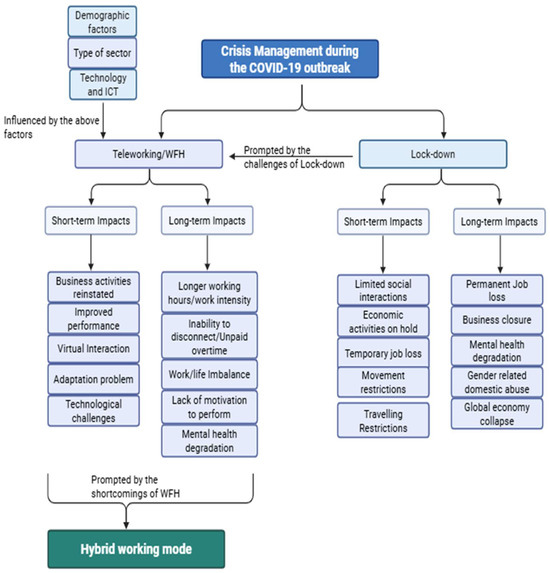

Looking at trends from past events, social interventions in crisis management have consistently proven effective on a short-term adoption scale [53,54]. In most cases, these measures were never meant to fully resolve the crisis, but rather to manage its impact while awaiting more permanent solutions. During the COVID-19 pandemic, both lockdown and WFH arrangements emerged as highly effective interventions and were arguably among the most impactful available options at the time. Although they were implemented in close succession and often interdependently, each served a distinct purpose and functioned differently over time. Lockdown primarily aimed to reduce the rate of virus transmission by limiting physical contact between individuals. In contrast, WFH ensured the continuity of essential services and economic activity amid movement restrictions. Realistically, comprehensive lockdowns can only be sustained for a short period [55]. Prolonged lockdowns risk collapsing national economies and exacerbating societal issues. In regions where lockdowns persisted for longer durations, many individuals reported heightened levels of boredom and psychological stress, with negative consequences for mental health [56]. Moreover, a significant increase in domestic violence (particularly against women) was reported during extended lockdowns, often attributed to the enforced proximity of partners in tense or abusive household environments [57]. Additional socio-economic consequences included widespread business closures and job losses, further highlighting the unsustainable nature of extended lockdowns. These realities reinforce the notion that while lockdown is an effective immediate response, it cannot serve as a long-term solution. Conversely, WFH presents a different case, with both short- and long-term implications that vary widely, depending on organizational structure, individual circumstances, and technological readiness.

Initially, the introduction of WFH helped people reconnect with the outside world in a meaningful way, even when physical interaction was impossible due to comprehensive lockdowns [58]. It effectively brought work to the people and enabled virtual interactions that helped maintain a sense of community and productivity [59]. As such, the adoption of WFH provided much-needed relief to the public and helped resuscitate essential services within society. Many were able to return to work, albeit from the safety and comfort of their homes. However, the implementation of WFH was not without its challenges. Many employees struggled to adapt to this new mode of work, especially given the abruptness of its adoption [60]. Others lacked the necessary technological resources or expertise, requiring additional support and supervision [61]. Even when the system was fully operational, many workers found it difficult to unplug after regular working hours [62]. As a result, they often worked extra hours unintentionally and in many cases, without compensation [63,64]. These challenges underscore the fact that full-scale WFH impacts individuals and organizations differently over time. The long-term effects can be significant enough to necessitate alternative resilience strategies such as hybrid work models to mitigate the diminishing returns associated with prolonged remote working.

After working from home for an extended period, many employees found it increasingly difficult to unplug from work, experienced heightened feelings of loneliness, and struggled to stay motivated [52]. In addition to the challenges of disconnecting, some workers reported that their jobs became more intense over time under the WFH model [65]. This intensification may be a result of converting the time once spent commuting into additional working hours, thereby unintentionally extending the workday. In some cases, working hours even began earlier than usual, often under the pretext of virtual meetings, which further contributed to the sense of intensification [65]. Many teleworkers were observed to engage in unpaid overtime, working longer hours and investing extra effort in exchange for the flexibility to determine where and when they worked [66]. Increased job intensity and prolonged working hours have thus become common side effects of long-term teleworking, ultimately affecting employees’ work–life balance [39]. Initially, the core objectives of teleworking were to eliminate commute time and improve work–life balance [67]. While the elimination of commute time was clearly achieved, the improvement in work–life balance was more fleeting. Over time, the boundary between work and personal life began to blur, and many employees found themselves losing the balance they once had. Despite being perceived as more devoted, enthusiastic, and satisfied with their jobs, many workers struggled to draw a clear line between their home and work responsibilities after prolonged teleworking [68]. Over time, WFH began to feel increasingly similar to conventional office work for some employees. The initial excitement faded, and some workers reported that the experience no longer felt any different from working onsite. In terms of mental health, psychological challenges persisted for many, even while working remotely [65], particularly when reflecting on their experiences during the lockdown. Another emerging issue was the rise of presenteeism (where workers appeared to be engaged in work but were not genuinely productive). This was especially evident when employees were unwell but still expected to perform their duties remotely [69]. Overall, diminishing returns were observed over time, especially concerning perceived performance. Many employees acknowledged an initial boost in productivity after transitioning to remote work, but this surge did not last [70]. Motivation declined, and their perceived performance eventually mirrored that of their previous office-based routines or even fell below them [71].

From an organizational standpoint, long-term WFH has had positive cost implications for some companies, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) whose operations allow for the elimination of physical office spaces. However, many other companies were quick to call their staff back to the office [72], largely due to the challenges faced by management in effectively supervising remote workers. Despite these setbacks, the adoption of WFH across various job roles continues to rise in many organizations [73], indicating that the long-term effects of remote work are not entirely negative. In response to the challenges of sustained remote work, many companies have begun to implement hybrid work models. This approach allows employees to work from home on some days, while returning to the office on others, helping to preserve the benefits of WFH (such as reduced commuting time and improved work–life balance) while mitigating its long-term drawbacks. Moreover, the adoption of more flexible work arrangements, such as a four-day workweek instead of the traditional five, could help reduce the long-term impact of remote work on employees. Companies can also support their teleworkers by offering mental health packages, including access to paid therapy sessions and other wellness resources. For employees working under hybrid models, physical attendance at the office could be customized to suit individual needs. For example, mandatory in-office appearances could be limited to once every two weeks, giving workers the flexibility to choose when to work onsite. This would allow employees to manage their own balance, popping into the office when remote work feels isolating or overwhelming. After all, many workers reported that the aspect of teleworking they missed the most during lockdown was face-to-face interaction with their colleagues [65]. Maintaining some degree of in-person connection could therefore play a crucial role in sustaining morale and productivity in the long term. Figure 3 below presents an outline of the short- and long-term socio-economic impacts of implementing lockdown and WFH as crisis management measures during the lockdown.

Figure 3.

Outline of the socio-economic impacts of lockdown and teleworking as crisis management measures during COVID-19 outbreak, with influencing factors.

3.2. Industry-Specific and Demographic Variations in the WFH Implementation Process

At the organizational level, the impact of WFH has varied significantly across different industries and sectors. One major determinant of WFH adoption is company size, as larger organizations are generally more likely than smaller ones to implement flexible work arrangements like teleworking [74]. Additionally, not all professions can be performed remotely. The extent to which a job can be executed from home, commonly referred to as teleworkability, played a critical role in determining the feasibility of WFH during the COVID-19 pandemic, and it continues to do so today [75]. Another key factor in successful telework implementation is the availability of modern internet infrastructure and software tools. These technological enablers allowed many organizations to quickly deploy their workforce to remote setups. Unsurprisingly, WFH was initially adopted most easily by ICT-based companies, as they were already well-equipped with the necessary digital tools prior to the pandemic [33]. There has also been considerable discussion regarding the impact of lockdown on digital work tools and planning processes. The urgency of maintaining business continuity accelerated the adoption of new technologies across numerous industries [76]. In fact, since the pandemic, the pace of digitalization has increased notably, with more companies shifting toward technology-driven operations to enable remote work [38]. As a result, teleworking and ICT-based mobile work have expanded rapidly across various business models. Although initially implemented as a reactive measure following the lockdown, WFH has now become an integral part of many organizations’ operational strategies [39].

Nonetheless, the impacts of teleworking have varied significantly across different sectors, with some experiencing fewer challenges than others. For instance, individuals in ICT-based roles tend to report lower levels of technostress while working from home compared to workers in other sectors, who had to quickly adapt to using unfamiliar technologies to enable remote work [77]. While this gives ICT professionals a distinct advantage, they often face difficulties in maintaining a healthy work–life balance, as they are more likely to become engrossed in work and neglect personal activities [78]. The academic sector presents a different scenario. Teachers’ productivity during remote work has been observed to fluctuate over time [79], largely influenced by the level of student engagement and cooperation [80]. Many students, especially during online classes, face distractions in their home environments or struggle with connectivity issues, which in turn affects the effectiveness of the teaching process. These challenges are less prevalent in traditional classroom settings, where physical presence helps minimize distractions and technical interruptions [81]. In contrast, workers in the service industry experienced relatively fewer disruptions. Many service providers had already implemented online service options (particularly via telephone) even before the pandemic to reduce office congestion and minimize physical contact with clients [82]. This was especially true for the banking sector, where mobile banking apps and online customer support systems were already widely used [83]. In the healthcare sector, although most doctors and nurses remained on the frontlines and had to work physically in hospitals, there was a notable rise in telemedicine services [84]. Online and telephone consultations became common, with in-person visits limited to cases requiring close monitoring or surgical intervention. Public sector employees, however, generally reported lower productivity levels while working from home over time. It became common for these workers to extend their duties into non-working hours [85]. Many initially experienced technostress [86], which later evolved into a lack of motivation and increased distractions from their home environments, all contributing to a decline in perceived performance [87]. Across nearly all sectors, supervisors reported difficulties in effectively monitoring their teams remotely [88], which contributes to a general reluctance to adopt long-term teleworking as a permanent work model.

The socio-demographic impacts of WFH offer another dimension to the varied perspectives on teleworking, with different groups experiencing its effects in distinct ways. Minority demographics—such as individuals with disabilities, elderly employees, women with caregiving responsibilities, and residents of rural or remote areas, have gained improved employment prospects due to the widespread adoption of teleworking [39]. The growing popularity of WFH has particularly expanded opportunities for people with disabilities, enabling many to secure paid employment that may have been inaccessible to them previously [89]. However, if organizations were to mandate a full return to physical offices, it could potentially reverse these gains, especially for individuals with physical disabilities who might struggle to commute or navigate traditional workspaces. In such cases, they may face unemployment or have to make considerable efforts to attend in-person work, which could further marginalize them. Although the availability of jobs remains limited for some people with disabilities (whether remote or in-person), the shift to WFH has led many employers to adopt a more inclusive attitude, especially when their business models support remote operations [90]. That said, the benefits of WFH have not been equally distributed. Digital infrastructure disparities between urban and rural areas have hindered many rural residents from fully capitalizing on remote work opportunities [91]. As a result, the potential of teleworking remains underutilized in numerous rural communities. Interestingly, some urban-based teleworkers have begun relocating to rural areas, driven by the flexibility of remote work and the reduced need to live in densely populated cities. This migration has contributed to a noticeable population increase in some rural communities [92].

Teleworking has also revealed notable differences in impact across gender lines, with women generally showing a greater inclination toward working from home than other segments of the workforce [93]. This trend is largely attributed to the fact that women often bear the primary responsibility for childcare, unlike men, who have been observed to prefer other household tasks over direct childcare [94,95]. The need to balance professional duties with family and childcare responsibilities has thus made remote work a more appealing option for many women. Mothers of young children, in particular, have reported experiencing higher levels of psychological distress compared to those without such caregiving responsibilities [96]. This group also reported greater difficulty in maintaining a balance between work and personal life during the lockdown compared to their male counterparts [40]. One major reason cited was the frequent interruptions from children who require constant attention, which significantly hinders a woman’s ability to achieve or maintain a healthy work–life balance. Furthermore, women are statistically more likely than men to experience cyberbullying and online harassment while teleworking [97], contributing to heightened levels of psychological distress and depression. The issue of domestic violence also intensified during the COVID-19-related lockdown, with increased vulnerability reported among female teleworkers across the EU [98]. This raises serious concerns about the home environment being a safe space for all. Conversely, many men reported higher levels of job satisfaction while teleworking, often finding it more enjoyable than traditional office-based work [99]. Interestingly, some studies found that women, despite the additional challenges, reported no decrease in work efficiency following the shift to teleworking [100], suggesting a potentially higher level of adaptability or resilience. In contrast, male gender has been associated with lower perceived productivity in certain studies [101]. Nevertheless, increased productivity has been reported by many teleworkers across both genders, indicating that while gender-specific experiences differ, the overall effectiveness of WFH is not limited by gender alone [102].

In terms of age, older workers have generally reported greater satisfaction with WFH, appreciating the opportunity it offers to spend more quality time with their families [103]. However, another study indicated no significant difference in job satisfaction among teleworkers across different age groups, although it did find that younger workers tend to prefer the conventional office-based work mode [104]. Interestingly, a separate study showed that both Gen Z and baby boomers reported higher levels of job satisfaction compared to that reported by other generational groups [105]. Regarding job performance, younger workers are more likely to report higher productivity, partly due to their greater familiarity and comfort with ICT tools compared to that of older workers [106]. Older teleworkers, by contrast, faced notable challenges during the initial adoption of WFH, often struggling with technologies such as video conferencing and digital collaboration tools due to their limited prior exposure [107]. Nonetheless, older workers have been observed to better manage the balance between work and nonwork activities than their younger counterparts [108], indicating a more effective optimization of remote work arrangements. Additionally, during the lockdown, many older teleworkers leveraged their life experience to reframe the crisis as an opportunity for personal growth and development [109]. One reason younger professionals often struggle to achieve a functional work–life balance is their relative lack of professional experience, both in identifying what they value and in maintaining harmony between personal and professional domains [110]. Concerning mental health, psychological distress among teleworkers has been found to correlate more strongly with factors such as habits, work demands, and educational level rather than demographic variables like age [111]. Generally, flexible work arrangements like WFH have been observed to impact employees’ physical and mental well-being across all age groups [110]. Moreover, the ability to maintain a positive mental state while teleworking is often attributed more to access to health-related resources and the effective use of personal resilience strategies than to age itself [112].

Younger, unmarried workers were reported to suffer the most mental health challenges associated with WFH during the restrictions imposed by the lockdown [113]. While workers living with family members had the advantage of in-person social interaction [114], younger, single individuals likely experienced heightened levels of loneliness, boredom, anxiety, and other psychosocial stressors due to isolation. In some cases, productivity levels showed no significant differences among new teleworkers across various demographics, including marital status [115]. Parenthood has also been identified as a contributing factor to conditions that influence both mental health and quality of life among teleworkers [116]. For example, teleworking mothers have reported more frequent distractions and interruptions during work hours compared to other teleworkers, which can negatively affect their productivity [117]. In households with children and partners, background distractions have been cited as a key factor contributing to inconsistent job performance while working from home [118]. Male parents, however, have been reported to work fewer hours than female parents, which may explain their higher job satisfaction, while females reported experiencing greater levels of fatigue [119]. Overall, the implications of marital status and parenthood appear to be more significant among female than male teleworkers, suggesting that targeted support measures are necessary to improve the WFH experience for women [120].

Table 1 below gives a summary of the varying impacts of WFH across different sectors and socio-demographic groups, along with key influencing factors, as earlier discussed.

Table 1.

Summary of sectoral and demographic variations in the socio-economic implications of adopting WFH.

4. Addressing Knowledge Gaps and Future Considerations

The long-term societal impact of WFH on urban economies can only be fully understood through its continued adoption by professionals across various sectors. Without sustained practice, the full scope of its implications may remain underexplored. A shift in organizational culture to better accommodate WFH is essential in addressing ongoing uncertainties about its long-term viability and evolution. While the hybrid work model is currently popular among professionals, its long-term sustainability is still uncertain. Therefore, further research into the hybrid model is crucial to understanding its socio-economic and public health implications [121,122]. Viewing WFH as more than just a work arrangement, but also as a public health and societal intervention will help reveal its broader impacts, particularly those witnessed during the lockdown period. Furthermore, if hybrid work is considered a direct outcome of WFH, it is worth exploring what the future progression of hybrid work might look like. Such foresight could inform strategies surrounding organizational resilience and crisis management. Additionally, further studies are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of WFH across different demographic groups and professional sectors, alongside continued implementation and observation over time.

Despite the widespread and near-universal implementation of lockdown measures and the global adoption of WFH during the COVID-19 pandemic, several crisis management implications remain unresolved. Key uncertainties persist around fundamental concepts such as employee productivity and performance over extended periods of remote work. While some studies suggest that teleworking may positively impact workers’ mental health [123,124], others challenge this assumption, indicating that experiences can differ significantly across demographic groups [109,125]. These contrasting perspectives underscore the need for continued research into the socio-economic impacts of both lockdown and WFH, with careful consideration of all relevant factors and demographic variations.

Additionally, it is important to emphasize the factors responsible for the varied experiences reported by workers across different sectors during teleworking. Identifying and understanding these factors will help employees become more aware of the potential challenges they may face and enable them to better manage or even prevent possible shortcomings. Future studies could explore these variations through cause-and-effect evaluations, examining how different conditions contribute to different outcomes. Furthermore, the role of time in the implementation of WFH should be a key consideration—particularly in assessing whether significant differences exist between short- and long-term impacts, and between periods of crisis and non-crisis. This temporal perspective can offer deeper insights into the sustainability and effectiveness of remote work practices.

5. Limitations of the Study

This study is not based on original research and does not include primary data, which constitutes a major limitation. The absence of empirical evidence may increase the potential for bias in the interpretations and conclusions drawn. Additionally, as a conceptual review, the scope of this study is inherently limited compared to that of a systematic review, which would typically encompass a broader and more rigorous examination of the existing literature. Nonetheless, the objective of this study is to highlight the importance of the subject and to encourage further empirical research in this area. The timeframe also poses a limitation; a longitudinal approach would have provided deeper and more comprehensive insights into the long-term implications of WFH than those currently available.

6. Recommendations

Based on the projections of this study and the lessons learned from the COVID-19 crisis, it becomes imperative to recognize lockdown and WFH as vital crisis management measures. As such, clearly defined guidelines for their implementation should be developed in preparation for potential future crises. Organizations should incorporate the crisis management framework and resilience theory cycle into their operational models on a continuous basis. This would allow for ongoing assessment of both current and emerging situations, ensuring a more adaptive response. Moreover, policies for implementing crisis response measures, such as lockdown and WFH, should be structured in phases, with adjustments made based on the evolving nature and severity of the crisis. For instance, total lockdown should no longer be the immediate response, given its substantial negative economic impacts experienced globally. Instead, a combination of less severe interventions—such as temporary curfews and limited social gatherings—can be initially employed and subsequently re-evaluated based on real-time assessments. Employers should also be mandated to offer tailored support to employees depending on their specific WFH challenges and to regularly review teleworking conditions to ensure maximum effectiveness. This will help staff adapt more efficiently to WFH arrangements, making future deployments more seamless. Furthermore, the financial burden of setting up a functional home office should not fall solely on employees. Employers must bear this cost without reducing employee compensation, and standardized requirements for home office setups should be introduced. These standards must prioritize ergonomic considerations and ensure that all teleworkers have access to a productive and health-conscious work environment.

Moreover, on the subject of WFH, many professionals continue to work from home despite being called back to their physical workplaces [121,122]. This highlights that WFH remains a significant mode of work for a substantial number of employees. However, due to the challenges experienced during its rapid implementation amidst the pandemic, WFH has evolved into various forms across different professions. In most cases today, employees no longer work entirely from home but instead split their time between remote and onsite work, following a hybrid work model [126,127]. Others may even engage in frequent travel or “work-from-anywhere” arrangements, while maintaining full-time roles [128], often to avoid the monotony and psychological challenges associated with prolonged WFH [52,56]. In light of these developments, it is strongly recommended that both policymakers and employers continue to support and refine the hybrid work model. Progressive, employee-centered policies should be introduced to ensure its sustainability. For instance, regulations could define appropriate working hours for teleworkers to help prevent excessive overtime and ensure that any extra hours worked are properly compensated. Additionally, employers should be required to offer comprehensive support packages tailored to the unique needs of remote workers. This could include fully paid therapy sessions or mental health support programs, with employers actively encouraging their utilization. Finally, there is a need for the regular reassessment of key performance indicators (KPIs) for remote workers. By aligning KPIs with the realities of WFH, organizations can better assess whether telework remains a suitable option for each employee, based on its impact on performance and well-being.

Meanwhile, many businesses are believed to have already begun re-evaluating their human resource policies and workforce strategies in response to expected developments in the labor market following the pandemic. These efforts are largely aimed at enhancing employee adaptability to hybrid working arrangements, which are generally considered less challenging than full-time WFH. Despite these efforts, it is essential that organizations demonstrate a greater willingness to implement the previously discussed recommendations and policy suggestions. Doing so will not only yield more favorable outcomes but also foster an organizational culture that is more receptive to hybrid work. Furthermore, early research conducted during the onset of the pandemic emphasized that the COVID-19 crisis presented a unique opportunity to explore the potential of remote working and distance learning. It also opened up new avenues for international collaboration and cross-border employment opportunities [129]. Therefore, further research on this subject is strongly encouraged. In particular, longitudinal studies are necessary to assess the long-term impacts of WFH and its sector-specific implications. Additionally, comparative studies between the hybrid work model and traditional WFH practices would provide valuable insights into the sustainability, effectiveness, and adaptability of these evolving work models.

7. Conclusions

The goal of this study was to assess the socio-economic impacts of lockdown and WFH as crisis management measures during the COVID-19 outbreak and to explore the influence of sector types and demographic characteristics on their implementation and outcomes. The findings from this study indicate that both lockdown and WFH were critical components of crisis management during the pandemic. Their implementation revealed a range of outcomes, confirming their relevance and effectiveness in times of public health emergencies. Positive outcomes, included improved job satisfaction, reduced commuting, enhanced flexibility, and in some cases, increased performance. More importantly, these measures were instrumental in curbing the spread of the virus and preventing total economic collapse. The study also illustrated how the application of lockdown and WFH aligns with both the crisis management framework and the resilience theory, emphasizing the importance of continuous risk assessment and adaptive planning for future crises. Nonetheless, these strategies were not without challenges. Issues such as work–life conflict, decreased productivity, and mental health concerns (particularly boredom and loneliness) emerged, especially as long-term consequences. This reinforces the significance of time as a crucial variable when assessing the impacts of crisis response measures. While this study has provided valuable insights, considerable gaps remain due to ongoing debates and the complexity of the subject. These findings highlight the urgent need for further empirical and longitudinal studies, particularly in relation to the emerging hybrid work model. Such research will be vital to guide future adaptations and to develop more effective practices tailored to various sectors and demographic groups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.V.A.; methodology, D.V.A.; validation, G.B.; investigation, D.V.A.; resources, D.V.A.; writing—original draft preparation, D.V.A.; writing—review and editing, D.V.A., O.M.A. and C.B.; visualization, G.B., O.M.A. and C.B.; supervision, G.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the moral support of Izuchukwu Obasi and Seun Oladipupo contributed to this manuscript as well as their thoughtful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Monto, A.S.; Fukuda, K. Lessons from Influenza Pandemics of the Last 100 Years. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 70, 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, E.; Koopmans, M.; Go, U.; Hamer, D.H.; Petrosillo, N.; Castelli, F.; Storgaard, M.; Al Khalili, S.; Simonsen, L. Comparing SARS-CoV-2 with SARS-CoV and Influenza Pandemics. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, e238–e244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, B.K.; Verma, M.; Verma, V.K.; Abdullah, R.B.; Nath, D.C.; Khan, H.T.A.; Verma, A.; Vishwakarma, R.K.; Verma, V. Global Lockdown: An Effective Safeguard in Responding to the Threat of COVID-19. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2020, 26, 1592–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onyeaka, H.; Anumudu, C.K.; Al-Sharify, Z.T.; Egele-Godswill, E.; Mbaegbu, P. COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review of the Global Lockdown and Its Far-Reaching Effects. Sci. Prog. 2021, 104, 00368504211019854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Hakak, I.A.; Amin, F. Assessing the Coronavirus Research Output: A Bibliometric Analysis. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 0, 0972150920975116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabeil, N.F.; Pazim, K.H.; Langgat, J. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis on Micro-Enterprises: Entrepreneurs’ Perspective on Business Continuity and Recovery Strategy; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3612830 (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Belzunegui-Eraso, A.; Erro-Garcés, A. Teleworking in the Context of the COVID-19 Crisis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux-Dufort, C.; Lalonde, C. Editorial: Exploring the Theoretical Foundations of Crisis Management. J. Conting. Crisis Manag. 2013, 21, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pursiainen, C. The Crisis Management Cycle; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, S. Crisis Management: Planning for the Inevitable; Amacom, American Management Association: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ziek, P. Crisis vs. Controversy. J. Conting. Crisis Manag. 2015, 23, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisis Management: A Communicative Approach. In Public Relations Theory II; Botan, C.H., Hazleton, V., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jaques, T. Issue Management and Crisis Management: An Integrated, Non-Linear, Relational Construct. Public Relat. Rev. 2007, 33, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, J.L.; Haffenden, R.A.; Bassett, G.W.; Buehring, W.A.; Collins, M.J., III; Folga, S.M.; Petit, F.D.; Phillips, J.A.; Verner, D.R.; Whitfield, R.G. Resilience: Theory and Application; U.S. Department of Energy Office of Scientific and Technical Information: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2012; ANL/DIS-12-1. [CrossRef]

- Rutter, M. Resilience: Some Conceptual Considerations. In Social Work; Routledge: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cutter, S.L.; Burton, C.G.; Emrich, C.T. Disaster Resilience Indicators for Benchmarking Baseline Conditions. J. Homel. Secur. Emerg. Manag. 2010, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, G.T.; Kolluru, R.; Smith, M. Leveraging Public-private Partnerships to Improve Community Resilience in Times of Disaster. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2009, 39, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-T.; Hu, J.-L.; Kung, M.-H. Economic Resilience in the Early Stage of the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Across-Economy Comparison. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budnitz, H.; Tranos, E. Working from Home and Digital Divides: Resilience during the Pandemic. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2022, 112, 893–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberly, J.C.; Haskel, J.; Mizen, P. “Potential Capital”, Working From Home, and Economic Resilience; w29431; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R.; Luo, J.; Liu, M.J.; Yu, J. Understanding Organizational Resilience in a Platform-Based Sharing Business: The Role of Absorptive Capacity. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, F.; Xue, B.; Wang, D.; Liu, B. Unpacking Resilience of Project Organizations: A Capability-Based Conceptualization and Measurement of Project Resilience. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2023, 41, 102541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Edgeman, R.; AlNajem, M.N. Exploring the Intellectual Structure of Research in Organizational Resilience through a Bibliometric Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): Increased Transmission Beyond China—Fourth Update. 2020. Available online: www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/SARS-CoV-2-risk-assessment-14-feb-2020.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2023).

- Summers, J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Lin, H.-H.; Barnard, L.T.; Kvalsvig, A.; Wilson, N.; Baker, M.G. Potential Lessons from the Taiwan and New Zealand Health Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Lancet Reg. Health-West. Pac. 2020, 4, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J. Lessons from South Korea’s COVID-19 Policy Response. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2020, 50, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinn, J.O. Introduction: Towards a Sociology of Pandemics. Curr. Sociol. 2021, 69, 435–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, T. Brazil’s Covid-19 Response Is Worst in the World, Says Médecins Sans Frontières. The Guardian, 15 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, H. US COVID Response Could Have Avoided Hundreds of Thousands of Deaths: Research. 2021. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-usa-economy-idUSKBN2BH1DK (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Shaman, J.; Galanti, M. Will SARS-CoV-2 Become Endemic? Science 2020, 370, 527–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, P. The Social Perils and Promise of Remote Work. J. Behav. Econ. Policy 2020, 4, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvino, F. Kant on Remote Working: A Moral Defence. Philos. Manag. 2022, 21, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, A.; Leyer, M.; Steinhüser, M. Workers United: Digitally Enhancing Social Connectedness on the Shop Floor. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenbaum, Z. The Future of Remote Work. Monit. Psychol. 2019, 50, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Working from Home in the EU. 2018. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/DDN-20180620-1 (accessed on 6 April 2023).

- Richter, A.; Riemer, K. Malleable End-User Software. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2013, 5, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The Future of (Remote?) Work in the Public Service; Finding a New Balance Between Remote and In-Office Presence; OECD: Paris, France, 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Office. Teleworking During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond: A Practical Guide; International Labour Organisation (ILO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lodovici, M.S.; Ferrari, E.; Paladino, E.; Pesce, F.; Frecassetti, P.; Aram, E.; Hadjivassiliou, K.; Junge, K.; Hahne, A.S.; Drabble, D. The Impact of Teleworking and Digital Work on Workers and Society: Special Focus on Surveillance and Monitoring, as Well as on Mental Health of Workers; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas Llave, O.; Mandl, I.; Weber, T.; Wilkens, M. Telework and ICT-Based Mobile Work: Flexible Working in the Digital Age; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gangl, M.; Ziefle, A. Motherhood, Labor Force Behavior, and Women’s Careers: An Empirical Assessment of the Wage Penalty for Motherhood in Britain, Germany, and the United States. Demography 2009, 46, 341–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Van der Horst, M. Women’s Employment Patterns after Childbirth and the Perceived Access to and Use of Flexitime and Teleworking. Hum. Relat. 2018, 71, 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimura, A.; Yokoi, K.; Ishibashi, Y.; Akatsuka, Y.; Inoue, T. Remote Work Decreases Psychological and Physical Stress Responses, but Full-Remote Work Increases Presenteeism. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 730969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steidelmüller, C.; Meyer, S.-C.; Müller, G. Home-Based Telework and Presenteeism across Europe. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 62, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, A. The Coronavirus Is Making Us See That It’s Hard to Make Remote Work Actually Work. 2020. Available online: https://time.com/5801882/coronavirus-spatial-remote-work/ (accessed on 6 April 2023).

- Prasad, K.; Vaidya, R.W.; Mangipudi, M.R. Effect of Occupational Stress and Remote Working on Psychological Well-Being of Employees: An Empirical Analysis during COVID-19 Pandemic Concerning Information Technology Industry in Hyderabad. Indian J. Commer. Manag. Stud. 2020, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanti, T.; Guidetti, G.; Mazzei, E.; Zappalà, S.; Toscano, F. Work from Home during the COVID-19 Outbreak: The Impact on Employees’ Remote Work Productivity, Engagement, and Stress. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, e426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Becerik-Gerber, B.; Lucas, G.; Roll, S.C. Impacts of Working from Home during COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical and Mental Well-Being of Office Workstation Users. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Kiran, U.; Pandey, P.; Sharma, V. Remote Working and Its Impact on Upper Extremities. J. Ecophysiol. Occup. Health 2021, 21, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, S.; Maimaiti, R. Remote Working in the Period of the COVİD-19. J. Psychol. Res. 2021, 03, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Qian, J.; Parker, S.K. Achieving Effective Remote Working during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Work Design Perspective. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 70, 16–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, B.R.; Mukhopadhyay, B.K. Managing Remote Work: Changes, Challenges, and Choices. 2021. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/356503361_Managing_Remote_Work_Changes_Challenges_and_Choices#fullTextFileContent (accessed on 6 April 2023).

- An, B.Y.; Porcher, S.; Tang, S.-Y.; Kim, E.E. Policy Design for COVID-19: Worldwide Evidence on the Efficacies of Early Mask Mandates and Other Policy Interventions. Public Adm. Rev. 2021, 81, 1157–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Done, A.; Voss, C.; Rytter, N.G. Best Practice Interventions: Short-Term Impact and Long-Term Outcomes. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, R.; Luhar, S.; Khan, N.; Choudhury, S.R.; Matin, I.; Franco, O.H. Long-Term Strategies to Control COVID-19 in Low and Middle-Income Countries: An Options Overview of Community-Based, Non-Pharmacological Interventions. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 743–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutzer, F.; Frajo-Apor, B.; Pardeller, S.; Plattner, B.; Chernova, A.; Haring, C.; Holzner, B.; Kemmler, G.; Marksteiner, J.; Miller, C.; et al. Psychological Distress, Loneliness, and Boredom Among the General Population of Tyrol, Austria During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 691896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, C.; Carrington, K.; Ryan, V.; Warren, S.; Clarke, J.; Ball, M.; Vitis, L. Locked down with the Perpetrator: The Hidden Impacts of Covid-19 on Domestic and Family Violence in Australia. Int. J. Crime Justice Soc. Democr. 2021, 10, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wethal, U.; Ellsworth-Krebs, K.; Hansen, A.; Changede, S.; Spaargaren, G. Reworking Boundaries in the Home-as-Office: Boundary Traffic during COVID-19 Lockdown and the Future of Working from Home. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2022, 18, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, B.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Haag, M. Working from Home during Covid-19: Doing and Managing Technology-Enabled Social Interaction with Colleagues at a Distance. Inf. Syst. Front. 2023, 25, 1333–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu-Curtis, C.-H. Team Transition to Virtual (Remote) Work During COVID-19 in a Call Center Environment: An Exploratory Case Study. Ph.D. Thesis, Trident University International, Cypress, CA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2770097126/abstract/72D36574D82443DAPQ/1 (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Ortiz-Lozano, J.M.; Martínez-Morán, P.C.; Fernández-Muñoz, I. Difficulties for Teleworking of Public Employees in the Spanish Public Administration. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toniolo-Barrios, M.; Pitt, L. Mindfulness and the Challenges of Working from Home in Times of Crisis. Bus. Horiz. 2021, 64, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, L.B.; Scutelnicu, G.; Charbonneau, É. A Qualitative Study of Pandemic-Induced Telework: Federal Workers Thrive, Working Parents Struggle. Public Adm. Q. 2022, 46, 258–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayre, É.; Morin-Messabel, C.; Cros, F.; Maillot, A.-S.; Odin, N. Benefits and Risks of Teleworking from Home: The Teleworkers’ Point of View. Information 2022, 13, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillot, A.-S.; Meyer, T.; Prunier-Poulmaire, S.; Vayre, E. A Qualitative and Longitudinal Study on the Impact of Telework in Times of COVID-19. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelliher, C.; Anderson, D. Doing More with Less? Flexible Working Practices and the Intensification of Work. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.-V.; Vo-Thanh, T.; Nguyen, N.P.; Van Nguyen, D.; Chi, H. The COVID-19 Pandemic: Workplace Safety Management Practices, Job Insecurity, and Employees’ Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Saf. Sci. 2022, 145, 105527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felstead, A.; Henseke, G. Assessing the Growth of Remote Working and Its Consequences for Effort, Well-being and Work-life Balance. New Technol. Work Employ. 2017, 32, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biron, C.; Karanika-Murray, M.; Ivers, H.; Salvoni, S.; Fernet, C. Teleworking While Sick: A Three-Wave Study of Psychosocial Safety Climate, Psychological Demands, and Presenteeism. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 734245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troll, E.S.; Venz, L.; Weitzenegger, F.; Loschelder, D.D. Working from Home during the COVID-19 Crisis: How Self-Control Strategies Elucidate Employees’ Job Performance. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 71, 853–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akinwande, D.V.; Boustras, G.; Varianou-Mikellidou, C.; Dimopoulos, C.; Akhagba, O.M. Employee Teleworking (Working-from-Home) Experience Assessment during COVID-19 Lockdown: A Dual-Edged Sword. Saf. Sci. 2025, 183, 106732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, J.; Young, Z.; Bevan, S.; Veliziotis, M.; Baruch, Y.; Beigi, M.; Bajorek, Z.; Richards, S.; Tochia, C. Work After Lockdown: No Going Back: What We Have Learned Working from Home Through the COVID-19 Pandemic; University of Southampton: Southampton, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blahopoulou, J.; Ortiz-Bonnin, S.; Montañez-Juan, M.; Torrens Espinosa, G.; García-Buades, M.E. Telework Satisfaction, Wellbeing and Performance in the Digital Era. Lessons Learned during COVID-19 Lockdown in Spain. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 2507–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sostero, M.; Milasi, S.; Hurley, J.; Fernandez-Macías, E.; Bisello, M. Teleworkability and the COVID-19 Crisis: A New Digital Divide? JRC Working Papers Series on Labour, Education and Technology; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fana, M.; Milasi, S.; Napierala, J.; Fernández-Macías, E.; Vázquez, I.G. Telework, Work Organisation and Job Quality During the COVID-19 Crisis: A Qualitative Study; JRC Working Papers Series on Labour, Education and Technology; European Commission: Seville, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Matli, W. The Changing Work Landscape as a Result of the Covid-19 Pandemic: Insights from Remote Workers Life Situations in South Africa. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2020, 40, 1237–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, S.; Barrios, A. Teleworking and Technostress: Early Consequences of a COVID-19 Lockdown. Cogn. Tech. Work. 2022, 24, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, H.; Hislop, P.D. Home-Based Teleworkers: The Effect of Work Demands, Personality and ICT Use on Work>Nonwork Boundary Interruptions; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartkowiak, G.; Krugiełka, A.; Dama, S.; Kostrzewa-Demczuk, P.; Gaweł-Luty, E. Academic Teachers about Their Productivity and a Sense of Well-Being in the Current COVID-19 Epidemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotini-Shah, P.; Man, B.; Pobee, R.; Hirshfield, L.E.; Risman, B.J.; Buhimschi, I.A.; Weinreich, H.M. Work–Life Balance and Productivity Among Academic Faculty During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Latent Class Analysis. J. Women’s Health 2022, 31, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dontre, A.J. The Influence of Technology on Academic Distraction: A Review. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 3, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozuem, W.; Ranfagni, S.; Willis, M.; Rovai, S.; Howell, K. Exploring Customers’ Responses to Online Service Failure and Recovery Strategies during COVID-19 Pandemic: An Actor–Network Theory Perspective. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 1440–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, N.A.; Bayyoud, M. Impact of COVID-19 on UK Banks; How Banks Reshape Consumer Banking Behaviour during Pandemic. COVID 2023, 3, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccato, F.; Voltan, G.; Sabbadin, C.; Camozzi, V.; Merante Boschin, I.; Mian, C.; Zanotto, V.; Donato, D.; Bordignon, G.; Capizzi, A.; et al. Tele-Medicine versus Face-to-Face Consultation in Endocrine Outpatients Clinic during COVID-19 Outbreak: A Single-Center Experience during the Lockdown Period. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2021, 44, 1689–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mar, S.; Sokolic, D.; Buzeti, J. Work during Non-Work Time of Public Employees. Cent. Eur. Public Admin. Rev. 2022, 20, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarena, L.; Fusi, F. Always Connected: Technology Use Increases Technostress Among Public Managers. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2022, 52, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.A.; da Rosa, F.S. Control and Motivation in Task Performance of Public Servants at Home Office in the Face of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Rev. Gestão 2022, 30, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]