Abstract

The objectives of this study are to identify the importance of teleworking during the COVID-19 pandemic and, evaluate the future development of this working form, characterize the process, identify its benefits and challenges, and present some solutions to deal with telework. To this end, the following research questions were formulated: (1) What areas of telework had the most significant impact during the COVID-19 pandemic? (2) What is the impact of telework on productivity? (3) What are the positive and negative aspects of teleworking? (4) What solutions do leaders propose for telework to intensify in the future? The sample for this study consists of 159 participants holding managerial positions. The data analyses were completed and allowed us to study the challenges of leadership in teleworking in direct public administrations. The results indicate that productivity is maintained, although productivity has decreased in the education sector. The positive aspects found were flexibility, better time management, that communication became simpler, and greater motivation. As negative aspects, we found changes in leadership, communication, and lack of material. To minimise the negative aspects of teleworking, the leaders essentially mentioned mixed-work (face-to-face and teleworking), distribution of appropriate material, training, teleworking regulation, and productivity control.

1. Introduction

Unexpectedly, COVID-19 has changed the world in a way no one thought was possible. This situation poses a considerable challenge to the human resources of public and private organisations. A fast adaptation is needed to manage the resources while people are in “forced” teleworking. Effective e-leadership is essential to continue good results in this complex business environment for leaders and employees.

Before the outbreak of COVID-19, due to evolving customer demands and emerging options from technological innovations and the financial crisis, change processes had already become essential in the public sector [1].

The public sector is being tested to its limits by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has swept away the standard repertoire of foresight, protection, and resilience strategies, and brought society and the economy to a near halt [2].

Leaders at all levels of the hierarchy play a crucial role in managing organisational Paradoxes such as COVID-19. Paradoxical leadership has been defined as a “leader’s sense-giving to followers about the necessity to execute contradictory yet interrelated behaviours simultaneously to constructively deal with paradoxes and tensions in their work environment” [3].

According to [3], hat leaders who are better adaptable in paradoxical situations are more effective in leading people in complex, ambiguous, and contradictory work environments. Because paradoxes are prevalent in the public sector, public employees whose leaders support them in tolerating an ambiguous work environment and in accepting conflicting needs should be more satisfied with their jobs. Followers might show positive attitudes and behaviours in response to their subjective perceptions of leadership.

In a highly innovative and positive culture, there are often transformational leaders, who are based on premises such as the idea that people are trustworthy and have a purpose, each one manages to make a unique contribution, and complex problems are solved at the lowest possible level [4].

According to [5], effective leadership best matches behaviour, context, and need. In this sense, to truly understand a leader’s efficiency, it is necessary to understand the context in which he leads.

The COVID-19 pandemic reveals that the public sector is facing more complex problems that must be solved. The future capacity to respond to turbulent problems such as COVID-19 requires several strategies that the leaders must implement. In a study by [6], the authors concluded that efforts to decrease the formalisation and centralisation of decision-making processes to allow for greater participation by administrative staff and their leaders would enhance a transformational leadership culture.

In the future, the leadership role in the public sector will become even more demanding due to the rapid development of digitalization. As more modularised and easily integrated the organisation is, the more it will tend to adapt to new and emerging demands [2]. In the view of [7], this type of leadership has proven to be beneficial for the success of virtual teams. Before COVID-19, teleworking was steadily growing globally across many sectors. This new way of working can be found frequently in public administrations all over Europe [8]. The author suggests that empirical studies show that this new way of working in terms of temporal and spatial flexibility can improve working conditions, work outcomes, and quality of work. However, careful implementation of new ways of working is needed to secure the positive effects and reduce potential adverse side effects, such as the intensification of work or the blurring of boundaries between work and private life.

The pandemic accelerated this process, and now companies must operate with employees having to work in places different from the traditional workplace through teleworking. Managing teleworking employees means that there will be additional tasks and responsibilities for mid-level managers and direct supervisors, particularly in the early stages of introducing teleworking [9].

Teleworking is a flexible working method that is not limited by time, location, type of communication technology, and the use of information. The successful implementation of this requires technology, social, and organisational support, specifically in the form of e-leadership practices where the emergence of digital technology, and internet services have facilitated the progress of teleworking [10].

It can be a very effective work arrangement tool if correctly implemented, coupled with a range of available resources such as training and the appropriate technology [9]. The authors also enumerate the potential benefits of teleworking, which may include employee retention and cost savings, a higher level of flexibility and work-life balance, improved productivity, environmental friendliness, higher employee satisfaction, fewer work disruptions, resilience, and emergency preparedness.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) officially announced the outbreak of the coronavirus disease on 11 March 2020 as a pandemic and suggested preventive measures to contain its spread. Telework was an important measure suggested by the World Health Organisation (2020) and was successfully implemented organisations and governments worldwide.

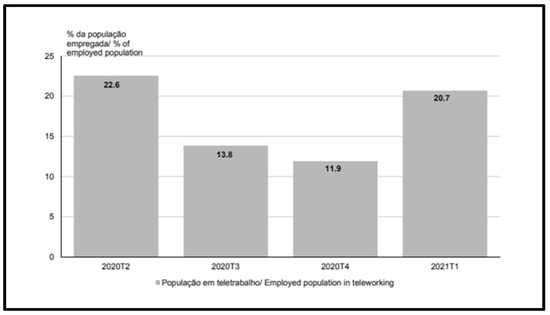

Portugal had the first cases on the 2nd of March, and 22nd of March the Government declared telework obligatory until the 1st of August. Telework became obligatory between 4 November 2021 and 6 January 2022. In the second quarter of 2020, the most significant proportion (22.6%) of the population was always employed or almost always in telework. In the third and fourth quarters of 2020, with the slowdown of the measures to contain the pandemic and the growing lack of definition, this proportion decreased, but has increased again in the first quarter of 2021, with the implementation of new restrictive measures and new confinement [11] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Statistics Portugal, Labour Force Survey (2022). Source: Statistics Portugal, Labour Force Survey (2022).

Next, the data show that the employed population who always worked or almost always were at home in the reference week and the three weeks before, according to the use of ICT—Information and Communication Technology:

This study approaches the challenges of teleworking for leaders in public administration from the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020). To study the effect of telework during the COVID-19 pandemic, this study attempts to answer the following questions:

- Question 1: What areas of telework had the most significant impact during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- Question 2: What is the impact of telework on productivity?

- Question 3: What are the positive and negative aspects of teleworking?

The study tries to present solutions to view teleworking as an opportunity. With this purpose, the question was formulated:

- Question 4: What solutions do leaders propose for telework to intensify in the future?

1.1. Portuguese Public Administration

1.1.1. Organisation

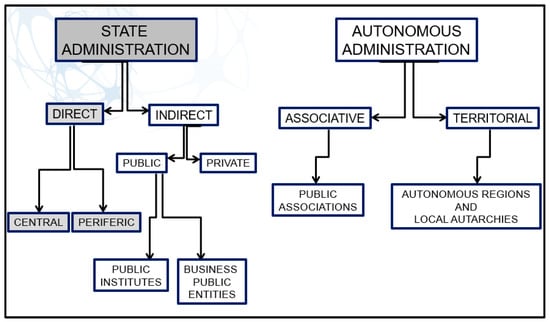

The authors in [12] present the structure and organisation of the Portuguese public administration: State Administration and Autonomous Administration (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Adapted from Amaral (2014).

The State Administration is divided into direct (central and peripheric) and indirect (public and private). We can find public institutes and public business entities in the indirect administration.

In the autonomous administration (the islands of Madeira and Açores), we have the associative (public associations) and the territorial (autonomous regions—the islands of Madeira and Açores and the local autarchies).

1.1.2. Operation

Management in the direct administration of the State is based on management by objectives. Management by objectives presupposes the clarification and understanding of the objectives by employees and public managers, the analysis of the best alternatives to achieve the objectives, and the identification of the time and effort necessary to achieve them [13]. Management by Objectives (MBO) is a management model characterized by planning and performance evaluation through quantifiable objectives and the use of indicators and targets.

The desire of the public administration is only to design institutions and management systems conducive to attracting professionals competent to manage the public policy process following the law [14]. It assumes that managers must be able to apply effective strategies so that organisations can fulfil their missions and create public value in the following years [15].

In this model, it is expected that the organisation’s employees have prior knowledge of the objectives to be achieved by them. Knowledge of the desired ambition feeds the self-assessment process of employees during the execution of their tasks to guarantee the achievement of the desired positive performance identified in the goals; and, at the same time, they foster employee motivation and a sense of belonging.

1.1.3. Evaluation

In Portugal, assessment is carried out through the Performance Management and Assessment System (SIADAP). This establishes the integrated management and performance evaluation system (Services, Managers, and Workers) in public administration. Law No. 66-B/2007 established it on 28 December, and it was amended by Law 66-B/2012, on 31 December—LOE 2013.

Its objective is to improve the performance and quality of service of the public administration. It applies to the services of direct and indirect administration of the State and, with the necessary adaptations concerning the powers of the corresponding organisms, to the services of the autonomous regional administration and the municipal administration.

There are three types: SIADAP 1, 2, and 3, respectively: The Public Administration Services Performance Assessment Subsystem, abbreviated as SIADAP 1 (annual assessment cycle); The Performance Assessment Subsystem of Public Administration Managers, abbreviated as SIADAP 2 (assessment cycle from 3 to 5 years); and The Public Administration Workers Performance Assessment Subsystem, abbreviated as SIADAP 3 (biennial).

The final evaluation results from the weighted average scores obtained in the two evaluation parameters. A minimum weighting of 60% is assigned to the “Results” parameter, and a maximum weighting of 40% to the “Skills” parameter. The final evaluation is expressed in qualitative mentions depending on the final score in each parameter in the following terms: relevant performance, final evaluation from 4 to 5, adequate performance, final rating from 2 to 3,999, inadequate performance, and final rating from 1 to 1,999.

A self-assessment is requested from the assessed, which aims to involve in the assessment process and identify opportunities for professional development.

It is mandatory and is carried out by filling in a specific form to be analysed by the evaluator, if possible, together with the person being evaluated, with a preparatory nature for the attribution of the evaluation not constituting a binding component of the performance evaluation. The recognition of excellence through the attribution of the qualitative mention of relevant performance is subject to appreciation by the Evaluation Coordinating Board. However, they have a limited number of attributions.

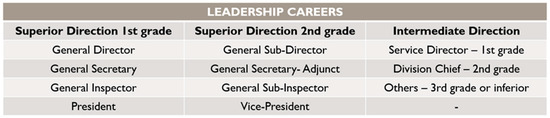

1.2. Leadership Positions

Management positions include direction, management, coordination, and control of public services and workers. Managerial positions are qualified for senior and intermediate management positions, depending on their hierarchical level, competencies, and responsibilities (DGAEP, 2022) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Leadership Careers. Source: DGAEP—2022.

The senior manager must meet the following requirements: Degree completed for at least 10 or 8 years, linked or not to the public administration, have technical competence, aptitude, professional experience, and training appropriate to their respective functions.

The middle manager must meet the following requirements: workers in public functions, graduates endowed with technical competence, and with experience in the exercise of similar functions for 6 or 4 years.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Collection Procedure

To have real information about the leaders’ challenges in the Portuguese public administration, a survey was sent to all the direct public administration services. In May 2022, the survey was sent to a total of 972 organisations and 159 of them responded (a sample of 16.4%).

The questionnaire had seven questions with a direct and fast response. It was sent by email with the link to the platform Google Forms. It contained information about the purpose of the study and the confidentiality of the answers was also guaranteed. The participation was voluntary and all of the responses were considered for the statistics. The sampling process was non-probabilistic and for convenience [16].

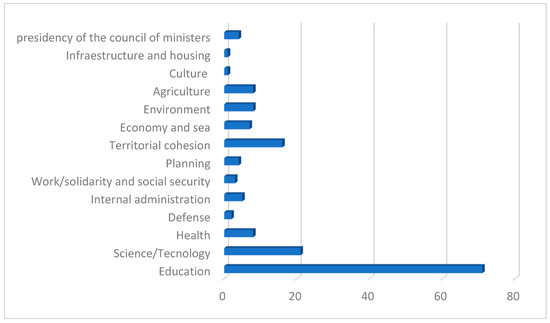

2.2. Participants

The 159 participants of this study have middle and senior management positions, currently working in a central public administration organism of the State. Among the one hundred and fifty-nine participants, four (2.5%) work in the presidency of the council of ministers, one (0.6%) in infrastructure and housing, one (0.6%) in culture, eight (5%) in agriculture, eight (5%) in environment, seven (4.4%) in the economy and sea, sixteen (10.1%) in territorial cohesion, four (2.5%) in planning, three (1.9%) in work/solidarity and social security, five (3.1%) in internal administration, two (1.3%) in defense, eight (5.1%) in health, twenty-one (13.3%) in science/ technology, and seventy-one (44,7%) in education (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Distribution of participants according to the organisation at which they work.

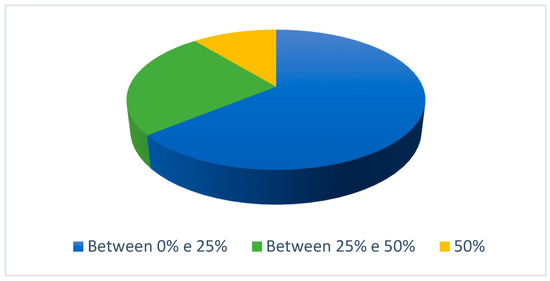

Regarding the team they lead, one hundred and sixteen (73%) of the participants affirmed that the percentage of employees telecommuting is equal to or less than 25%, nine (5.7%) that it are between 25% and 50%, and thirty-four (21.7%) that are above 50% (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Percentage of workers currently teleworking.

2.3. Data Analysis Procedure

Data were imported into SPSS Statistics software. Descriptive statistics were performed for the seven questions that make up the questionnaire.

Then, it was verified if the fact that the participants are linked to education influences the percentage of telecommuting workers and if the same influences productivity by performing chi-square tests.

2.4. Instruments

The instrument used in this study consists of seven questions, all of which were authored by the researchers of this study, based on other authors’ questionnaires. The questions are as follows: (1) What service do you work for? (2) What is the percentage of workers in telework at this moment? (3) In which areas did telework during the COVID-19 pandemic have more impact? (4) Regarding productivity in telework, decreased, kept up or increased. (5) Regarding leadership, enumerate some positive aspects of telework. (6) Regarding leadership, enumerate some negative aspects of telework. (7) Which solutions can you indicate to minimize the negative impacts of telework?

3. Results

Descriptive statistics were used to analyse all the questions formulated in this study.

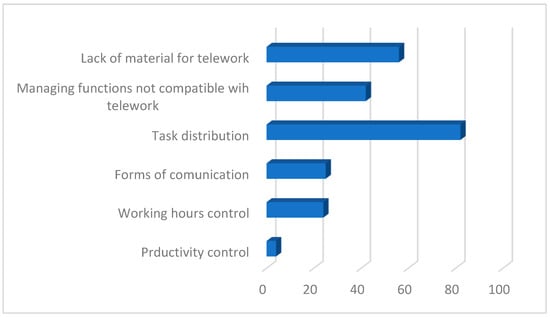

In response to the question “In which areas did telework during the COVID-19 pandemic have more impact?” the following results were obtained: four (2.5%) of the participants mentioned productivity control; twenty-four (15.1%) the working hours’ control; twenty-five (15.5%) the forms of communication; eighty-two (51.6%) the task distribution; forty-two (26.4%) the managing functions not compatible with telework; fifty-six (35.2%) the lack of material for telework (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Areas of telework during the COVID-19 pandemic with the most impact.

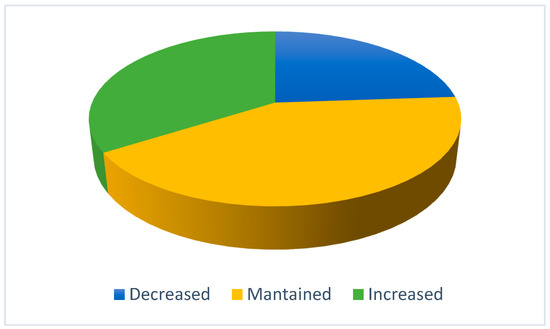

In response to Question 4, “Regarding productivity in telework: decreased, kept up or increased?”, 38 (23.9%) of the participants reported that productivity decreased, 67 (42.1%) that it was maintained, and 54 (34%) that it increased (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Productivity in telework.

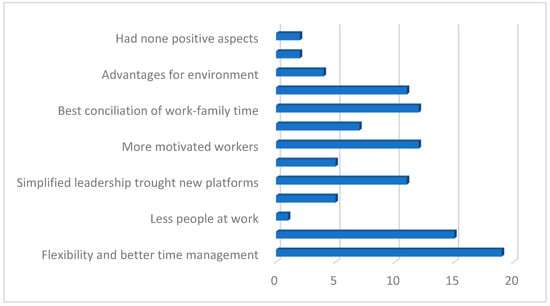

Answering the question “Regarding leadership, enumerate some positive aspects of telework”, nineteen (11.9%) of the participants referred to flexibility and better time management, fifteen (9.4%) that simplified communication, one (0.6%) fewer people at work, five (3.1%) an individual Responsibility, eleven (6.9%) that simplified leadership through new platforms, five (3.1%) better performance in institutional objectives, twelve (7.5%) more motivated workers, eleven (6.9%) an increase in productivity, four (2.5%) as advantages for the environment, two (1.3%) savings, and two (1.3%) stated that they had no positive aspects (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Positive aspects of telework.

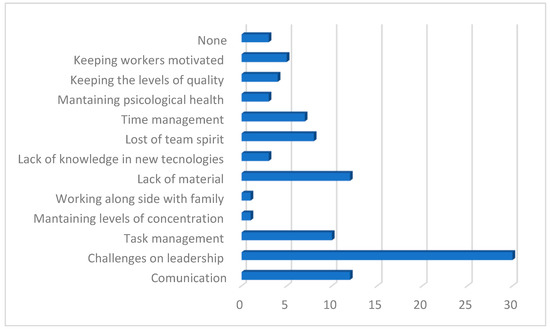

When answering the question “Regarding leadership, enumerate some negative aspects of telework”, the participants mentioned: twelve (7.5%) communication, thirty (18.9%) challenges in leadership, ten (6.3%) task management, one (0.6%) maintaining levels of concentration, one (0.6%) working alongside with family, twelve (7.5%) lack of material, three (1.9%) lack of knowledge in new technologies, eight (5%) loss of team spirit, seven (4.4%) time management, three (1.9%) maintaining psychological health, four (2.5%) keeping the levels of quality, five (3.1%) keeping workers motivated, and three (1.9%) stated that there were no negative aspects (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Negative aspects of telework.

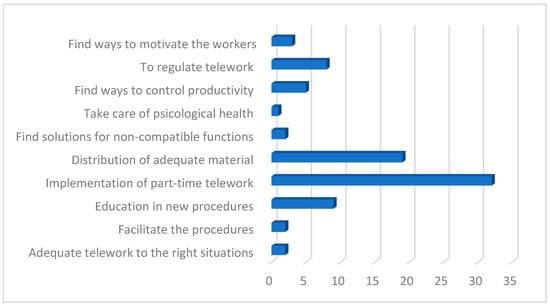

Finally, when answering the question “Which solutions can you indicate to minimize the negative impacts of telework”, the participants mentioned the following suggestions for improvement: two (1.3%) adequate telework in the right situations, two (1.3%) facilitate the procedures, nine (5.7%) education in new procedures, thirty-two (20.1%) implementation of part-time telework, nineteen (11.9%) distribution of adequate material, two (1.3%) find solutions for non-compatible functions, one (0.6%) take care of psychological health, five (3.1%) find ways to control productivity, eight (5%) to regulate telework, and three (1.9%) find ways to motivate the workers (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Solutions to minimize the negative impacts of telework.

Next, as the number of education professionals was the largest group, we tried to understand whether belonging to education influences productivity.

The chi-square test indicated that education influences productivity (ꭓ2 (2) = 8.12; p = 0.017). Among the professionals in education, 24 (33.8%) stated that productivity decreased, while only 14 (15.9%) of the other professionals reported this decrease. The increase in productivity was reported by 18 (25.4%) of the education professionals and 36 (40.9%) of the other professionals (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of the chi-square test of productivity*education.

We then tried to understand if the percentage of employees who telecommute influences productivity.

The chi-square test indicated that this influence is not significant (ꭓ2 (2) = 7.62; p = 0.094). However, it can be seen that both leaders who have between 0% and 25% of employees teleworking and those who have between 25% and 50% mainly reported that productivity was maintained. On the other hand, leaders who have more than 50% of their employees teleworking reported that productivity increased (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of the chi-square test of the percentage of teleworking workers*productivity.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The objectives of this study were: to identify the importance of teleworking during the COVID-19 pandemic and in the future; to characterize the process and its challenges; to identify the benefits of teleworking; to identify the challenges of teleworking; and to present some future solutions to deal with telework.

Firstly, it was found that of the employees led by the participants of this study, a very small percentage (between 0% and 25%), are in telework. This is possible because 44.7% of employees work in education, and these were the first workers to return to face-to-face work. In the education branch, very few employees remained in telework, especially those who were teachers up to the 12th grade.

When asked about the areas with the most significant impact during COVID-19, most participants responded that it was the distribution of tasks, followed by the lack of material for telework, the control of productivity, and working hours. These results are due, once again, to the fact that most of the participants are coordinators of school clusters, and the teaching staff are aged and have little preparation for teleworking.

In the first place, productivity was maintained, followed by an increase and then a decrease. In turn, education professionals reported a higher percentage than other professionals that productivity decreased. In contrast, concerning the increase in productivity, the other professionals reported a higher percentage. Again, this is due to the enormous difficulty of teaching young students online. When we crossed the percentage of teleworking workers and productivity, it was the heads whose team was still mostly teleworking who reported a higher increase in productivity. These results are because professionals from branches other than education are the ones who are still mostly teleworking and these professions are more suitable for teleworking.

As positive aspects of teleworking, the participants mentioned flexibility and better time management, communication became simpler, and there was greater motivation. Regarding flexibility and time management, when teleworking employees do not spend time travelling it allows them to have more time for other tasks.

As negative aspects, they mentioned changes in leadership, communication, and lack of material. These results are in line with the results obtained by [6]. In this study, leaders highlighted communication as one of the main obstacles, often caused by a lack of technical equipment to lead conferences. The electronic equipment available is crucial to developing good leadership to improve trust and social exchange between leaders and the effectiveness of virtual teams. Naturally, they mentioned the leadership changes since many leaders had to change their leadership styles. In Portugal, the predominant leadership style was transactional [17], and with mandatory telework, the leader had to learn to delegate functions. To delegate functions, the leader must be highly motivated and have competent employees [18], which is not always the case. From the perspective of [7], transformational leadership can be beneficial in virtual teams since the leader must delegate roles, as mentioned.

Finally, to minimise the negative aspects of teleworking, they essentially mentioned mixed work (face-to-face and teleworking), distribution of appropriate material, training, teleworking regulation, and productivity control. Although there has been legislation regulating telework in Portugal (Lei 83/2021, de 6 de dezembro), many leaders consider it insufficient.

The main goals of this study were achieved. We managed to have a “portrait” of what percentage of workers are in telework actually in central public administration. The leaders identified the benefits and challenges of telework and enumerated solutions for the implementation, control, and regulation in the future. However, some limitations need to be pointed out. In this study, we had no control over who responded and could not perceive what organisations would participate. We could have selected organisms and conducted a more profound study with them. Some could have implemented some tools to structure the organisations and their responses. Moreover, this study was limited to central public administration, which gives space for future research comparing the data with other administrations and private organisations would be interesting. It would also be interesting to study the implementation of the solutions for telework that the companies adopted and try to realise what could be missing.

As practical implications, it is suggested that the public administration should provide its employees with the appropriate equipment to enable them to work faster in virtual teams. In the view of [6], the development of more up-to-date solutions for public administration should be considered a high priority. Special attention should also be paid to the training of leaders, regarding the acquisition of skills related to how to communicate, give feedback, motivate employees, and support them through electronic communication.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.F. and M.J.S.; methodology, E.F. and A.M.; software, E.F. and A.M.; validation, E.F., M.J.S. and A.M.; formal analysis, E.F. and A.M.; investigation, E.F. and A.M.; resources, E.F.; data curation, A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, E.F.; writing—review and editing, E.F., M.J.S. and A.M.; visualization, M.J.S.; supervision, M.J.S. and A.M.; project administration, E.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because all participants, before answering the questionnaire, had to read the informed consent and agree to it. It was the only way they could answer the questionnaire. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study and that the results were confidential, as individual results would never be known but would only be analysed in the set of all participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors. The data are not publicly available since, in their informed consent, participants were informed that the data were confidential and that individual responses would never be known, as data analysis would be of all participants combined.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kuipers, B.S.; Higgs, M.; Kickert, W.; Tummers, L.; Grandia, J.; van der Voet, J. The management of change in public organizations: A literature review. Public Adm. 2014, 92, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Sørensen, E.; Torfing, J. The COVID-19 pandemic as a game changer for public administration and leadership? The need for robust governance responses to turbulent problems. Public Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 949–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, L.; Reuber, A.; Vogel, D.; Vogel, R. Giving sense about paradoxes: Paradoxical leadership in the public sector. Public Manag. Rev. 2020, 24, 1478–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Transformational leadership and organizational culture. Public Adm. Q. 1993, 17, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, M. The Many Facets of Leadership; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Liebermann, S.C.; Blenckner, K.; Diehl, J.H.; Feilke, J.; Frei, C.; Grikscheit, S.; Hünsch, S.; Kohring, K.; Lay, J.; Lorenzen, G.; et al. Abrupt implementation of telework in the public sector during the COVID-19 crisis. Z. Arb. Organ. Psychol. 2021, 65, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, J.; Post, C.; DiTomaso, N. Team dispersion and performance: The role of team communication and transformational leadership. Small Group Res. 2019, 50, 348–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korunka, C.; Kubicek, B.; Risak, M. New Way of Working in Public Administration, Federal Ministry for the Civil Service and Sport, DG III—Civil Service and Administrative Innovation. Available online: https://www.eupan.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Study_New_Way_of_Working_in_Public_Administration.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Centre of Expertise for Good Governance. Toolkit on Teleworking in Public Administrations, Council of Europe. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/good-governance/centre-of-expertise-and-covid (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Contreras, F.; Baykal, E.; Abid, G. E-Leadership and Teleworking in Times of COVID-19 and Beyond: What We Know and Where Do We Go. Front. Psicol. 2020, 11, 590271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INE Statistics Portugal, Labour Force Survey. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmainxpgid=ine_tema&xpid=INE&tema_cod=1114 (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Amaral, D.F. A Administração Pública: Conceito de administração, Curso de Direito Administrativo, 3rd ed.; Almedina: Coimbra, Portugal, 2014; pp. 193–207. [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira, J. Guidelines Para a Elaboração do Plano Estratégico—Boas Práticas no Setor Público; Estratégia Elementar Books: Lisboa, Portugal, 2015; pp. 21–114. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, E. Decisão na Administração Pública: Diálogo de racionalidades. Sociol. Probl. Práticas 2013, 73, 131–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, J.M. Strategic Planning for Public and Nonprofit Organizations: A Guide to Strengthening and Sustaining Organizational Achievement; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 212–234. [Google Scholar]

- Trochim, W. The Research Methods Knowledge Base, 2nd ed.; Atomic Dog Publishing: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mota, T.S.P. Um Estudo Exploratório Sobre “má” Liderança e Sobre a Liderança Destrutiva em Portugal. Master’s Thesis, Universidade de Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hersey, P.; Blanchard, K.H. Management and Organizational Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).