As an indispensable component of human resources, supervisors play important roles in directing, evaluating, and coaching employees [

1]. Supervisors also play important roles in supporting employees’ work, fostering employees’ abilities, and empowering employees to achieve their career goals [

2]. The extant literature provides rich evidence that supervisors strongly impact employees’ physical and mental well-being [

3] because supervisors can enhance managerial effectiveness, promote organizational management practices, and create favorable conditions for employees [

4]. These benefits constitute a stream of study that focuses on the “bright side” of supervisor behaviors, which are essential in contributing to organizational prosperity.

Aside from the large body of research on the “bright side” of supervisor behaviors, there is a burgeoning sub-domain of supervisor behaviors that specifically focuses on workplace mistreatment, which is commonly referred to as the “dark side” of supervisor behaviors [

5]. These “dark side” behaviors embody mistreatment [

6] in which “at least one organizational member takes counter-normative negative actions or terminates normative positive actions against another member” [

7]. As a specific type of supervisor-initiated destructive behavior that generates hindrance stress [

8], abusive supervision, which refers to “subordinates’ perceptions of the extent to which supervisors engage in the sustained display of hostile verbal and nonverbal behaviors” [

9], has gained increasing attention from organization scholars [

10], because of its prevalence in the workplace [

11] and its indirect effect on employees’ physiological well-being [

12].

1. Concerns and Issues in Extant Literature

Despite the promising progress researchers have made in identifying antecedents and outcomes of abusive supervision [

4,

10], some critical questions about abusive supervision are still yet to be answered. Firstly, drawn from the theoretical framework that is built upon the Social Exchange Theory [

13], previous studies have provided support for the positive relationship between abusive supervision and workplace deviant behaviors, such as counterproductive work behaviors [

14]. However, when it comes to the supervisor-employee relationship, employees may consider reciprocating behaviors against supervisors highly risky, due to the power distance between supervisor and subordinate [

15]. As a result, although engaging in deviant behavior (e.g., counterproductive work behavior, CWB) is an option, employees might choose reconciliation, which describes employees’ proactive actions to repair and normalize the relationship with the supervisor [

16,

17], to respond to abusive supervisor.

Secondly, despite rich evidence shedding light on workplace deviance that responds to abusive supervision [

18], literature that explicates employees’ responses to abusive supervision after deviant behaviors is still underdeveloped. Building upon the idea of normalization of deviance, which describes an organizational phenomenon in which people consider deviant behaviors acceptable over time [

19], I propose that reconciliation would be less likely to be considered if deviant behaviors have been engaged at a higher level. In other words, engaging in deviant behaviors could inhibit reconciliation initiated by employees.

In addition, several factors that may moderate employees’ responses to abusive supervision are worth examining. Specifically, employees’ willingness to maintain a harmonious work atmosphere and their perceived value of the relationship with the supervisor are two factors that may moderate the effects of abusive supervision on employees because these factors are particularly important when it comes to interpersonal relationships. Therefore, this paper will address these unsolved questions through empirical investigation.

2. Theoretical Background of Abusive Supervision

As a typical example of workplace mistreatment, abusive supervision reflects workplace non-physical interpersonal behaviors initiated by supervisors [

9]. The Social Exchange Theory (SET) [

13] provides an explication of employees-initiated reciprocation to abusive supervision. According to the SET [

18], people’s interpersonal behaviors are not random and standalone, but “contingent on the actions of another person” [

20]. One important component that makes SET an overarching theory in abusive supervision literature is the principle of reciprocity [

21], which suggests that people who are treated in a certain way will feel obliged to reciprocate equivalently, either positively or negatively, to reflect justice, such that people receive what they deserve based on their deeds [

22]. When it comes to abusive supervision, this principle further suggests that people who are negatively affected by abusive supervision will respond by engaging in commensurate negative acts directed at the original perpetrator [

20].

3. Abusive Supervision and Expediency

Despite the belief that negative reciprocation is a normal response to mistreatment [

14,

20,

23], remedial actions can also be driven by mistreatment [

24]. As noted earlier, deviant behavior engagement fulfills people’s intention to reciprocate, however, not all employees who are negatively impacted by mistreatment would seek to engage in reciprocating behaviors that make the wrongdoers pay [

21] because reciprocating behaviors are subject to specific situations [

24], implying that the perceived appropriateness of negative reciprocity varies among different people. In fact, as suggested by [

17], when it comes to workplace mistreatment, some employees may choose to engage in functional responses, which represent behaviors that intend to solve problems constructively.

From the interpersonal perspective, there is a power distance, which refers to “the extent to which a society accepts the fact that power in institutions and organizations is distributed unequally” [

25] between the supervisor and employees, and power distance determines employees’ responses to injustice perceptions [

16]. Specifically, relative power inferiority emerges when subordinates evaluate their hierarchical status in comparison to that of their supervisor [

17,

26], making employees who are impacted by abusive supervision believe their options to reciprocate are limited [

15] and feel hesitant to engage in reciprocal behaviors [

16,

27].

Further, previous studies have indicated that power is the main component in a dyadic relationship between supervisor and subordinate [

28]. Under the circumstance of supervisory abuse, because of power distance, a subordinate may attempt to reconcile the relationship with the supervisor because it is expedient and beneficial for them to maintain a normalized relationship with higher-status individuals [

27], who control more resources [

29].

Reconciliation embodies a proactive, interpersonal behavior, such as being friendly, expressing the willingness to repair the current relationship and start a renewed relationship [

17,

24,

27], reflecting the effort initiated by employees to extend acts of goodwill toward abusive supervisors and repair the relationship [

30], and restoring the relationship [

27]. Therefore, choosing reconciliation would be helpful for subordinates to secure future rewards such as political and social advantages.

Hypothesis 1. There is a positive relationship between abusive supervision and employee-initiated reconciliation with an abusive supervisor.

4. Need for Harmony as a Moderator

Employees’ need for harmony can impact the effect of abusive supervision on reconciliation, such that employees who are willing to maintain group harmony and avoid group disintegration are more likely to engage in reconciliation with their abusive supervisor. In recent decades, the concept of “harmony” has been extended to business contexts. [

31] contended that harmony within an organization reflects the integration and embeddedness of an individual with an organization, representing an interrelated organizational network. From this standpoint, organizational harmony focuses on the level of agreement and fit among people within an organization, such that the higher the level of agreement and fit, the higher the organizational harmony, and vice versa [

32].

The essence behind organizational harmony is well-maintained interpersonal relations. In the organizational context, a person usually considers him/herself to be a “relational self”, such that a person’s organizational identity is defined by the role he/she assumes in the organization [

33]. When it comes to abusive supervision, the mistreatment undermines employees’ relational selves by putting stress and threats upon their relationships with their supervisors. Under this circumstance, if an employee considers his/her relational self to be important, this employee would be more willing to reconcile the relationship with the supervisor because reconciliation plays a significant role in repairing and normalizing the problematic relationship. On the other hand, if an employee does not worry about the jeopardized relational self, he/she will be less concerned about disintegrating the relationship with the organization and less willing to reconcile the relationship with the supervisor. In fact, as indicated by [

34], when an employee worries little about the jeopardized relationship within the organization, the employee would be less likely to engage in constructive and functional behaviors.

Further, From the institutional responsibility perspective, employees tend to maintain or enhance their individual legitimacy within the organization by engaging in socially desirable behaviors because legitimacy is important when it comes to promotion or other career advance in the organization [

35]. In the context of abusive supervision, due to the power distance between supervisors and subordinates, confrontation with abusive supervisors or other deviant behaviors disobey organizational norms, generate incongruence between the employee’s behaviors and organizational values and expectations, and undermine the employee’s legitimacy [

35,

36].

Building upon the concept of individual legitimacy, employees with a higher level of need for harmony would dial down negative emotions, refrain from engaging in workplace deviant behaviors and confrontation, and de-escalating the conflict [

27], whereas engaging in direct and explicit confrontation against supervisors has high risks of losing individual legitimacy within the organization. Therefore, employees’ need for harmony can impact the extent to which they would like to reconcile with the abusive supervisor.

Hypothesis 2. Employee’s need for harmony (NFH) moderates the positive relationship between abusive supervision and reconciliation, such that the relationship is more positive when the employee’s NFH is high but turns less positive when the employee’s NFH is low.

5. Abusive Supervision and Workplace Deviance

Engaging in deviant behaviors responds to abusive supervision in a dysfunctional way. Previous studies have indicated that abusive supervision is positively associated with engaging in deviant behaviors in the workplace [

27], such as counterproductive work behaviors (CWBs) [

9,

34], which refer to behaviors from employees that intend to jeopardize their employing organization or other members within the organization, and can be seen as the indicator or operationalization of workplace deviance—socially undesirable behaviors that significantly violate organizational norms and in so doing threatened the well-being of an organization, its members, or both [

37]. In the context of abusive supervision employees are more likely to engage in CWBs that are primarily toward employing organization (e.g., engaging in CWB-O), based on the idea of the supervisor’s organizational representation [

1].

As indicated by Eisenberger et al. [

1,

38], in the workplace context, employees identify their supervisors with their hiring organizations because supervisors act as agents of the hiring organization, with a legal, moral, and fiduciary obligation to work for the interests of the organization [

39]. Similarly, Byrne [

40] pointed out that supervisors can make themselves a unique representation of the organization by developing their decision-making process. Therefore, employees would infer that the supervisor can move beyond the individual person and embody the overall organization [

41], and what is really behind the mistreatment is the employing organization, the source of the mistreatment, and the deviant behaviors that reciprocate abusive supervision would be counterproductive work behaviors toward the organization (CWB-O).

Hypothesis 3. There is a positive relationship between abusive supervision and employees’ CWB-O engagement.

6. From Deviance to Reconciliation

Employees’ deviant behaviors (e.g., CWB-O) engagement is negatively related to reconciliation because of employees’ normalization of deviance. The idea of normalization of deviance describes an organizational phenomenon in which people consider deviant or socially undesirable behaviors would seem to normal and acceptable [

19,

42]. When an employee engages in deviant behaviors that intend to reciprocate abusive supervision, over time, the employee will feel his/her behaviors that go against the organizational norms and expectations are less problematic, making them feel less pressured to engage in activities that undermine their legitimacy within the organization [

35]. As a result, over time, employees who engage in deviant behaviors would be less willing to reconcile the relationship with an abusive supervisor because they feel engaging in deviant behaviors makes employees believe deviance is acceptable, and it is unnecessary to constructively normalize the relationship with the abusive supervisor.

Hypothesis 4. There is a negative relationship between CWB-O and employee-initiated reconciliation with an abusive supervisor.

7. Value of Relationship as a Moderator

Employees’ perceived value of the relationship between supervisor and employee impacts employees’ reconciliation engagement after deviant behaviors. As indicated by Hobfoll [

43], employees’ workplace behaviors are driven by the pursuit of future rewards and benefits. When an employee perceives his/her relationship with a supervisor to be valuable, with mutual respect and appreciation between supervisor and employee [

44], the employee will feel more obligated to reconcile and normalize the relationship with the supervisor after engaging in deviant activities because maintaining the valuable relationship with supervisor is the way to acquire and secure benefits and rewards from the supervisor [

17,

26]. In a similar vein, relationship quality impacts employees’ perceptions of the work environment and work attitudes [

45], such that people are more likely to “work it out” with blamed others (e.g., abusive supervisor) in situations whereby high-quality and valuable relationship exists [

24].

Therefore, in the case of abusive supervision, if an employee perceives the relationship with an abusive supervisor to be valuable, the expectation of potential benefits and future rewards from the supervisor outweigh the negative effect of the supervisor’s mistreatment, making employees feel more obligated to reconcile the relationship with their supervisor after their deviant behaviors.

Hypothesis 5. Employees’ perceived value of a relationship with an abusive supervisor (VOR) moderates the negative association between CWB-O and reconciliation, such that the relationship is less negative when employees’ perceived VOR is high but turns more negative when employees’ perceived VOR is low.

8. Study 1 Methods, Procedures, and Results

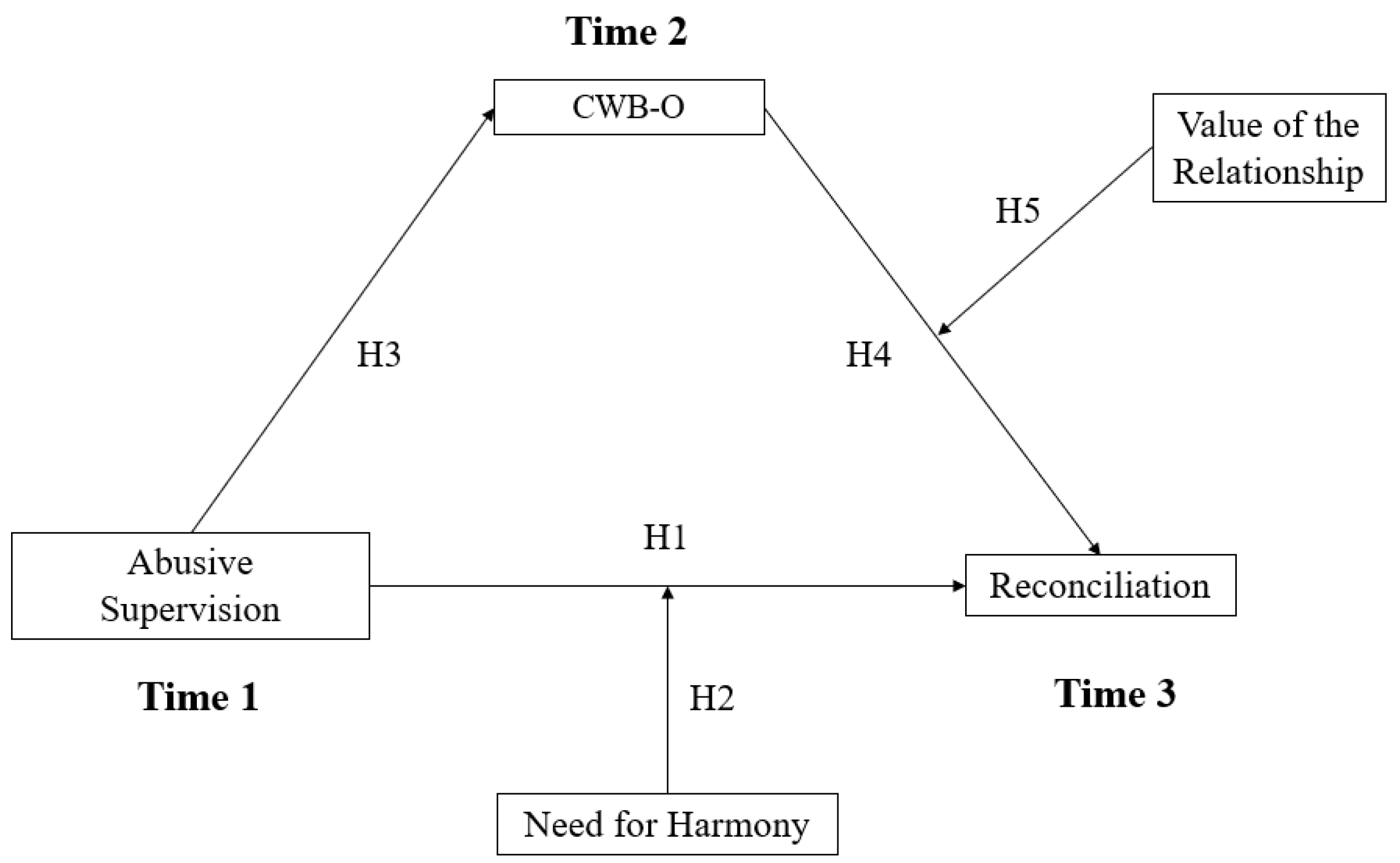

Figure 1 represents all hypotheses visually. Two studies were conducted to test the model, including one lagged-designed study (study 1) and one experiment (study 2). Study 1 empirically tested hypotheses 1 to 5 through three surveys administered to office-based working individuals in the service industry in the U.S. Study 2 recruited business school students from a university in the U.S., and utilized a between-subject, factorial design (2 × 2) experiment to examine the moderating effect of employees’ need for harmony (NFH) and the value of the relationship with supervisor (VOR) on reconciliation. By doing this, study 2 provided an additional test of the moderation effects.

9. Study 1 Sample and Procedure

Participant selection. Data was collected from a student-recruited snowball sample. Students in a U.S. university from multiple business classes invited working individuals from their acquaintances, friends, and family members working in the service industry and in office-based settings in the U.S. to participate in surveys. To ensure the data quality, two inclusion criteria were applied to each sample based on data collection quality maintenance practices [

46]. Firstly, only working individuals (i.e., people who are employed as part-time or full-time employees) were eligible to participate in the study. Secondly, participants had to have a supervisor to directly report to in their jobs when participating in the study.

Data collection procedure. For all participants, three surveys were delivered to reflect the temporal order of the conceptual model. Specifically, the first survey was administered in week 1, the second survey was administered in week 3, and the third survey was administered in week 5. The two-week interval is a reasonable interval for this type of study [

47].

Table 1 indicates the variables measured at each time point.

The surveys were delivered electronically through Qualtrics, an online survey tool. To reduce social desirability bias and to protect participants’ rights, a cover letter was provided at the beginning of the survey to request recipients’ voluntary participation and ensure the protection of privacy [

48]. A total of 276 working individuals participated in the time 1 survey, among which 223 of them finished the time 2 survey, and 195 of them finished the time 3 survey.

10. Study 1 Measures

Except for the abusive supervision measurement scale, a Likert-type scale with a range from 1 to 5, with 1 indicating “strongly disagree”, 3 indicating “neither agree nor disagree” and 5 indicating “strongly agree” was employed. The following section describes the measurement of each construct.

Abusive supervision (ASUP). Employees perceived abusive supervision was measured by using the 15-item Abusive Supervision Scale developed by Tepper [

9]. By following the measurement developed by Tepper [

9], where “1” was “I cannot remember him/her ever using this behavior with me”, and “5” was “He/she uses this behavior very often with me”. The Cronbach Alpha of ASUP was 0.95.

Counterproductive work behaviors toward the organization (CWB-O). CWB-O was measured by using the 6-item scale developed by Dalal et al. [

49]. The Cronbach Alpha of CWB-O was 0.84.

Reconciliation (REC). REC was measured by adapting the 3-item Reconciliation Scale developed by Aquino et al. [

27]. In the context of this study, all items were adapted by adding “toward my supervisor” to reflect the supervisor-employee relationship. For instance, a sample-adapted item is “I made an effort to be friendlier and more concerned toward my supervisor”. The Cronbach Alpha for REC was 0.85.

The need for harmony (NFH). NFH was measured by using the 9-item Disintegration Avoidance Scale developed by Leung et al. [

50]. NFH was measured at time 1. The Cronbach Alpha for NFH was 0.79.

Value of the relationship (VOR). VOR was measured by using the short-revised version 3-item Working Alliance Inventory (WAI-SR) developed by Hatcher and Gillaspy [

51]. The Cronbach Alpha of VOR was 0.92.

Control variables. Control variables include age, gender, education, full-time/part-time work experience, working hours per week, and time that working with the current supervisor.

11. Study 1 Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations.

Table 2 presents the mean (M), standard deviation (SD), inter-correlations, and reliability of study variables. The effect sizes and the directions of the obtained correlations were consistent with expectations. As indicated in

Table 2, the reliability test indicated the Cronbach Alpha values of all constructs were between 0.79 and 0.95, which indicates a good level of reliability [

52,

53]. Some findings are worth mentioning here. For instance, abusive supervision is positively correlated with CWB-O (0.38 **) and reconciliation (0.16 *), and VOR is negatively correlated with CWB-O (−0.32 **).

Test of the measurement model. To assess the appropriateness of the measurement model, I performed a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) by using Mplus 8 [

54]. In this study, I specified five latent factors to represent ASUP, CWB-O, REC, VOR, and NFH. The fit of the 5-factor model indicated good fit with the data, with χ

2 (619, N = 276) = 1145.70,

p < 0.00, χ

2/df = 1.58; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.06; Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 0.90; comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.90; Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) = 0.06. In comparison, a model in which all items were loaded onto one single factor showed poor fit with the data, with χ

2 (629, N = 276) = 2897.62,

p < 0.00, χ

2/df = 4.61, RMSEA = 0.11, TLI = 0.56, CFI = 0.59, SRMR = 0.12. As indicated in

Table 3, these results suggest there is a significant model fit reduction (Δχ

2 = 1751.92, Δdf = 10) in the 1-factor model, compared with the 5-factor model [

55]. In the 5-factor model, all items achieved reasonable loadings, between 0.45 and 0.91 [

56,

57], except one NFH item with a loading of 0.35. The lower-loading NFH item was retained given past research providing evidence for the scale’s validity [

50,

58].

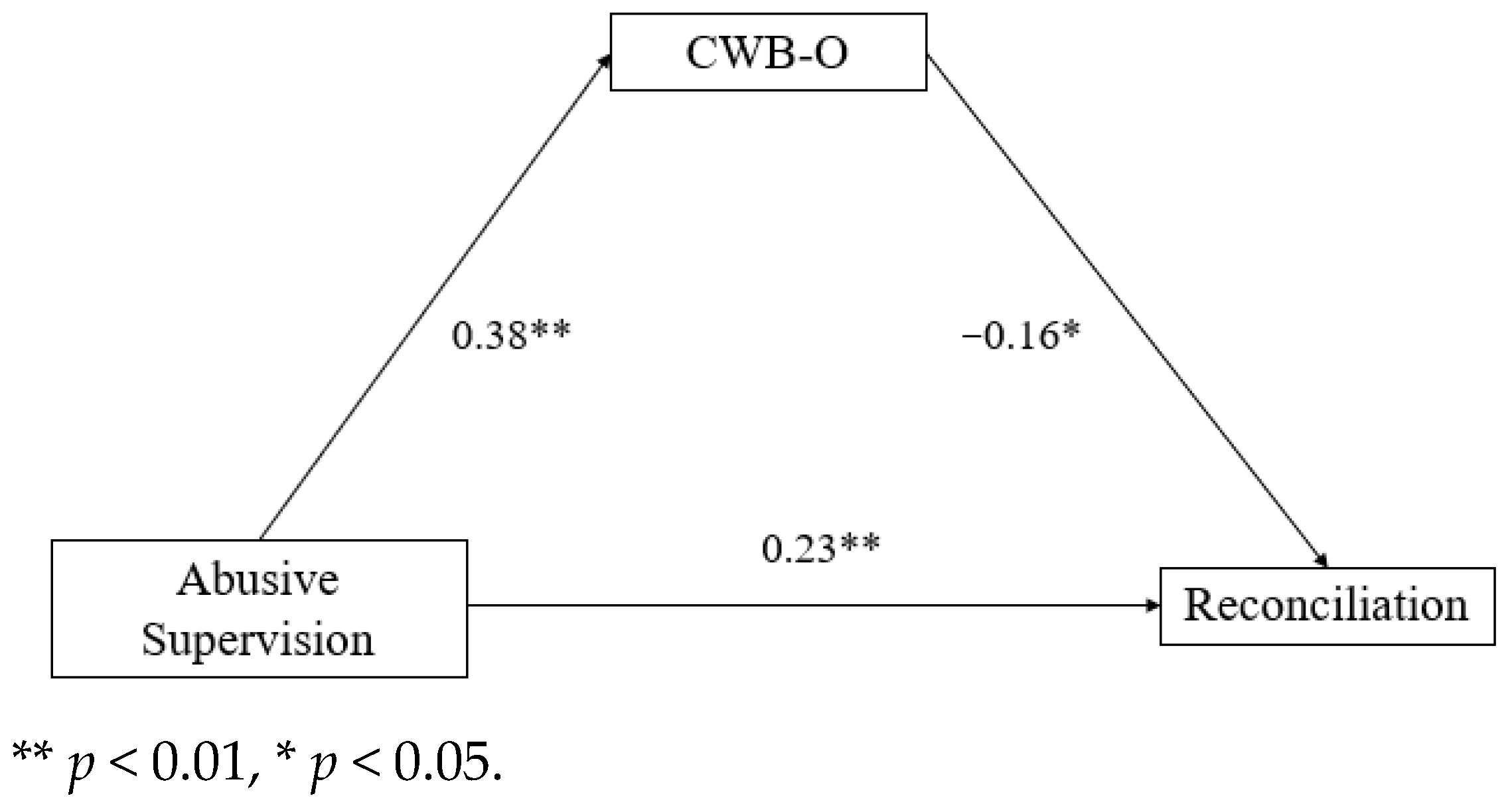

12. Hypotheses Testing

Mediation tests. Hypotheses were tested using Mplus 8 [

54]. Path analyses were employed to test the hypothesized effects from ASUP to REC, ASUP to CWB-O, and CWB-O to REC. As shown in

Figure 2 and

Table 4, the mediation model tested Hypothesis 1, which posited there is a positive relationship between ASUP and REC. The results indicated there is a positive and significant relationship (b = 0.23 **) between ASUP and REC. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

The mediation model also tested Hypothesis 3, which posited there is a positive relationship between ASUP and CWB-O. The results indicated there is a positive and significant relationship between ASUP and CWB-O (b = 0.38 **). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

Further, the mediation model tested Hypothesis 4, which posited that there is a negative relationship between CWB-O and REC. The results indicated a negative and significant relationship (b = −0.16 *) between CWB-O and REC. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

In addition, following the rules of testing indirect, direct, and total effects in a mediation model suggested by Edwards and Lambert [

59], I examined these effects by employing the following formulas. The results can be found in

Table 5. As shown in

Table 5, the results indicated there are significant positive direct effects and total effects in the mediation model, providing additional support to the hypothesized mediation.

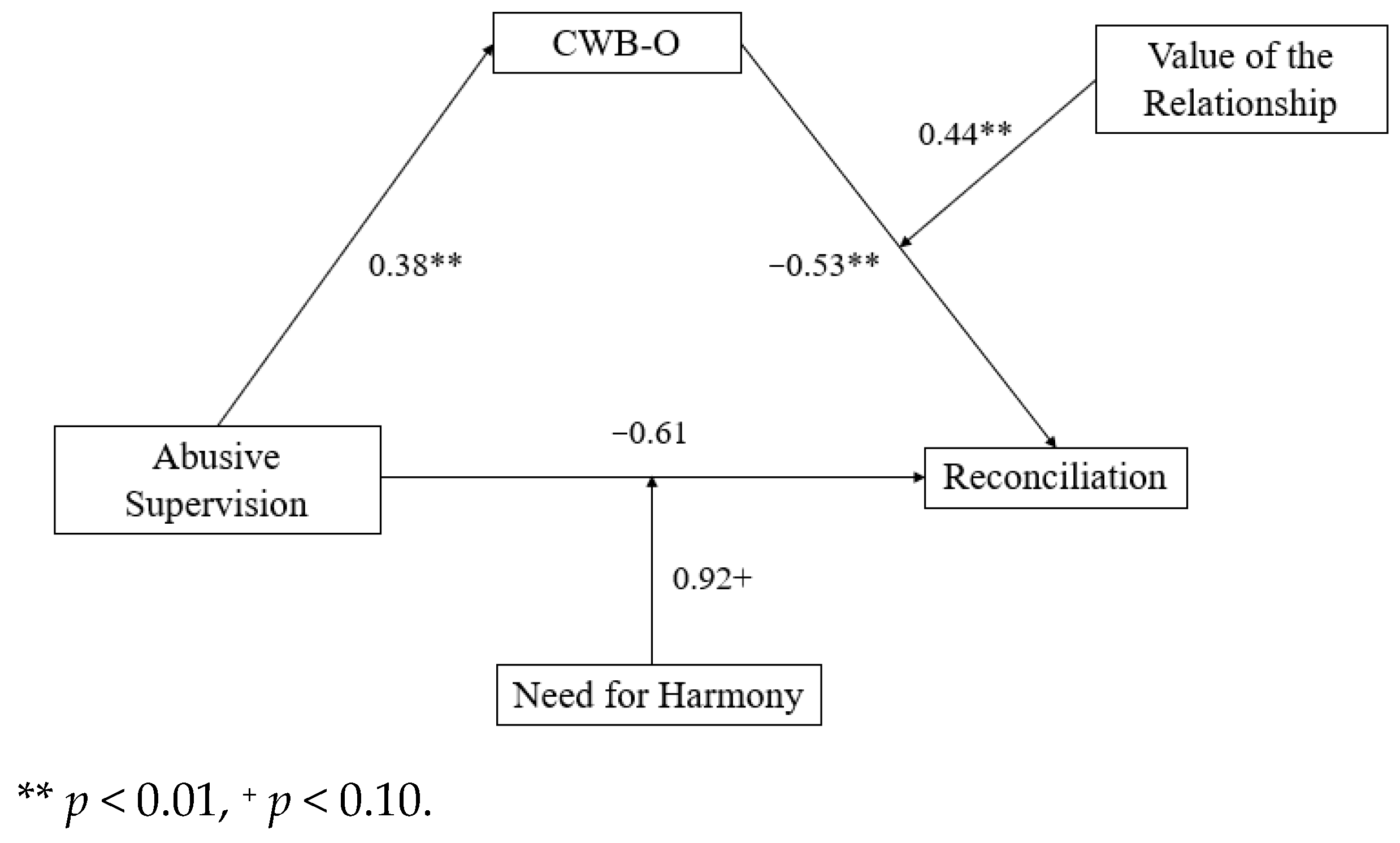

Moderated mediation tests. In the next step, I specified a moderated mediation model with two moderators (i.e., NFH and VOR) to test the moderation effects, which reflects hypotheses 2 and 5. As shown in

Figure 3 and

Table 6, the results indicated that NFH significantly moderated the relationship between ASUP and REC (b = 0.92

+), such that employees are more likely to engage in relationship reconciliation to respond to abusive supervision when NFH is at a higher level. This result provided support to Hypothesis 2.

Figure 4 provides a visual representation of the moderation effect of NFH.

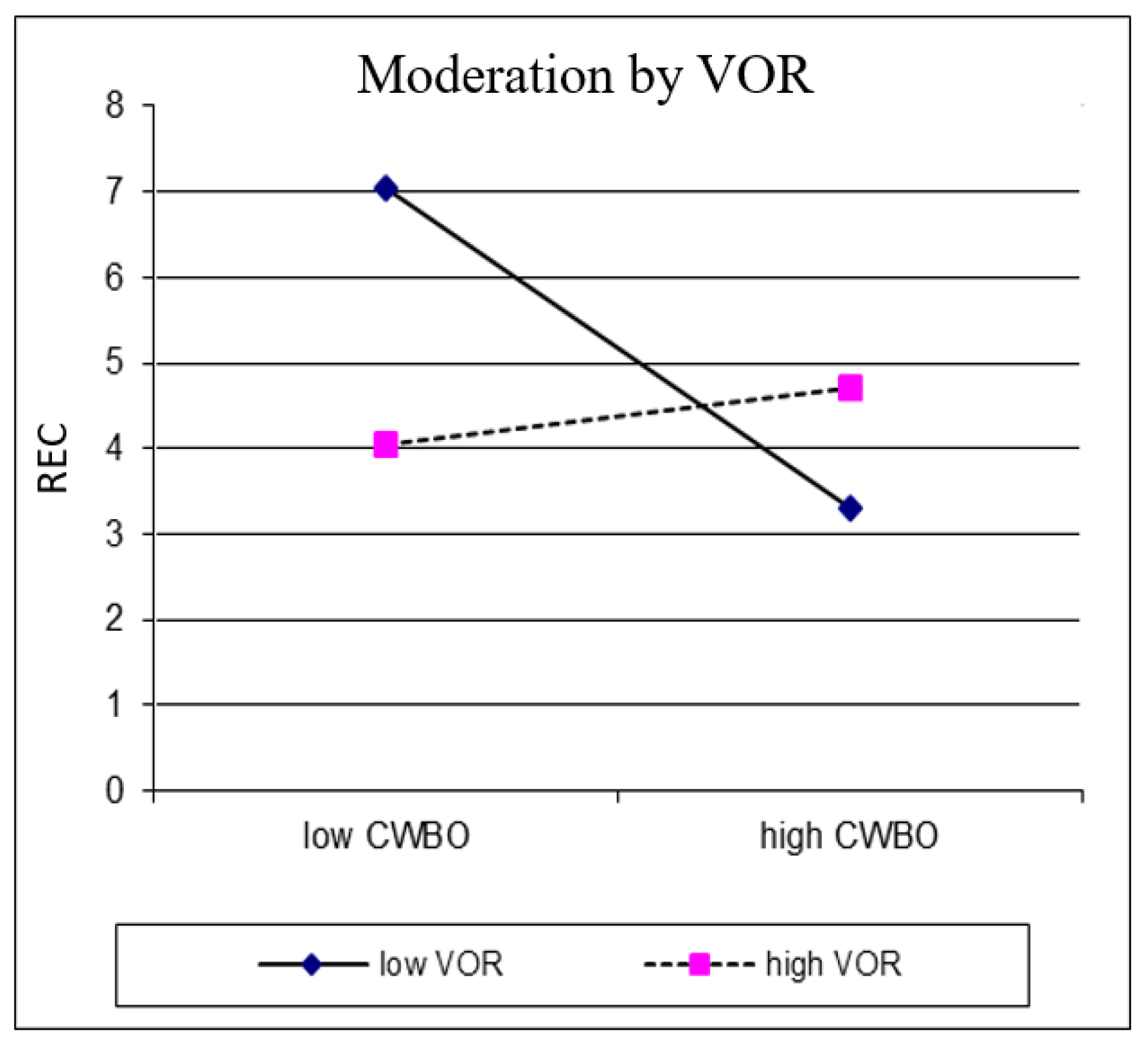

As shown in

Figure 3 and

Table 6, the results from the model indicated that VOR significantly moderated the relationship between CWB-O and REC (b = 0.44 **), such that employees are more likely to engage in REC following CWB-O, when VOR is at a higher level. This result provided support to Hypothesis 5.

Figure 5 provides a visual representation of the moderation effect of VOR.

13. Common Method Variance Test

To test common method variance and its potential biasing effect, I conducted an unmeasured latent method construct (ULMC) approach [

60]. After evaluating a five-factor measurement model (ASUP, VOR, NFH, CWB-O, and REC) and establishing acceptable fit (CFI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.06), I added an orthogonal latent common method factor to test for presence of common method effects (CFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.05). The ULMC accounted for an average of 28.6% of the variance in the substantive indicators, which is well below the cut-off of 70% [

61].

14. Study 1 Discussion

Study 1 yielded some results that deserve discussion. Although previous studies have shown that mistreatment within an organization evokes negative reciprocity towards those who are responsible for the mistreatment [

14], Study 1 results indicate that when it comes to supervisor-subordinate relationships, employees can respond to mistreatment by repairing and normalizing the relationship with wrongdoers, such that over time, employees are willing to engage in behaviors that reconcile their relationships with abusive supervisors. The results also indicated that employees’ need for harmony (NFH) impacts their reconciliation behaviors (REC), such that employees are more likely to engage in REC when their NFH is at a higher level.

Study 1 results also suggest that employees who experience abusive supervision and choose to respond with negative reciprocation (CWB-O) will be less likely to restore and normalize the relationship with the perpetrator, implying that once employees have engaged in negative reciprocating behaviors, they would not consider reconciliation to be a viable solution to workplace mistreatment. Further, despite the negative relationship between CWB-O and REC, the results indicated that employees’ perceived VOR impacts their REC engagement, such that employees are more likely to engage in REC following CWB-O engagement when perceived VOR is at a higher level.

Study 1 also has limitations. For example, study 1 is based on a survey-based study, which limits its ability to infer the causal relationship of interest. To address this limitation, study 2 employs two experiments with the manipulation of NFH (Study 2a) and VOR (Study 2b), which are the two moderators tested in study 1. Study 2 uses an experimental design that directly manipulated moderators (i.e., NFH and VOR), allowing me to replicate the results in Study 1 and draw stronger causal inferences from these moderators. Specifically, study 2a tested the effect of abusive supervision on reconciliation by manipulating NFH, and study 2b tested the effect of CWB-O on reconciliation by manipulating VOR.

15. Study 2 (2a and 2b) Methods, Procedures, and Results

Study 2a sampling. Participants were recruited from business school students in the U.S. A total of 181 students participated in this study, of which 163 students provided valid responses (90.1% of the total participants). Hinkin and Tracey [

62] and Schriesheim et al. [

63] posited that college students and individuals with a similar level of education have sufficient intellectual ability to answer job-related questions without being necessarily biased. Furthermore, 65% of participants were male. Participants averaged 20.70 (SD = 1.71) years, 0.63 (SD = 1.24) year of full-time work experience, 12.21 (SD = 14.26) working hours per week, and 0.86 years (SD = 1.41) of work with the current supervisor.

Study 2a procedure. Consistent with the experiment design in extant workplace mistreatment studies [

27], at the beginning of the experiment, participants were notified they will be presented with materials about abusive supervision and will be asked to situate themselves into the story, in other words, they were asked to imagine themselves as the recipient of hypothetical workplace mistreatment. The story included information about an abusive supervisor and manipulated NFH (high vs. low), such that participants are randomly assigned to either (1) high NFH or (2) low NFH condition [

Appendix A]. After reading the story, participants were asked to report their intention to reconcile.

Study 2a Measures. Study 2 measures began with manipulation check questions, followed by questions discussed below.

The need for harmony (NFH). NFH was measured by using the same scale used in study 1. To be used in the experiment context, all items were stated by using the same stem. A sample item is “based on this person’s experience, if you were this person, to what extent do you agree that when people are in a more powerful position than you, you should treat them in an accommodating manner”. The Cronbach Alpha of NFH was 0.91.

Reconciliation (REC). Reconciliation was measured by using the same scale used in study 1. To be used in the experiment context, all items were stated by using the same stem. A sample item is “based on this person’s experience, if you were this person, to what extent do you agree that you should make an effort to be friendlier and more concerned toward your supervisor?” The Cronbach Alpha of REC was 0.90.

Control variables. Control variables were the same as in Study 1.

Study 2a Results. Manipulation check. Since the need for harmony (NFH) was manipulated in study 2a, a manipulation check was performed to test whether this manipulation had the intended effect. An independent sample

t-test showed that participants’ perceived NFH was significantly higher in high NFH scenarios (M = 3.94) than in low NFH scenarios (M = 2.45), indicating that the manipulation of NFH was effective.

Table 7 provides maculation check results.

Effect on NFH. I performed an independent sample

t-test to examine whether the different levels of NFH can impact REC. The result provided support for the moderating effect of NFH. Specifically, as indicated in

Table 8, NFH significantly impacts participants’ willingness of engaging in reconciliation behaviors, such that participants were significantly more inclined to pursue reconciliation (M = 4.33) in the high NFH condition, compared with participants in the low NFH condition (M = 2.88).

Table 8 provides

t-test results as well.

Study 2b sampling. A total of 181 business school students in the U.S. participated in this study, of which 156 students provided valid responses (86.19% of the total participants). Furthermore, 58.97% of participants were male. Participants averaged 20.50 (SD = 1.24) years old, 0.59 (SD = 1.08) year of full-time work experience, 13.06 (SD = 15.45) working hours per week, and 0.52 years (SD = 0.78) of work with the current supervisor.

Study 2b procedure. Same as the procedure in study 2a, participants were notified they will be presented with materials about abusive supervision and will be asked to situate themselves into the story. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the two scenarios: (1) engaged CWB-O to respond to abusive supervision with manipulated high VOR and (2) engaged CWB-O to respond to abusive supervision with manipulated low VOR [

Appendix A]. After reading the story, participants were asked to report their willingness to reconcile with their abusive supervisor.

Study 2b Measures. Study 2 measures began with manipulation check questions, followed by questions discussed below.

Value of the relationship (VOR). VOR was measured by using the same scale used in study 1. To be used in the experiment context, all items were stated by using the same stem. A sample item is “based on this person’s experience, if you were this person, to what extent do you agree that your supervisor and you respect each other?” The Cronbach Alpha of VOR was 0.95.

Reconciliation (REC). Reconciliation was measured in the same way as Study 2a. The Cronbach Alpha of REC was 0.90.

Control variables. Control variables were the same as in Study 1.

Study 2b Results. Manipulation check. Since the VOR was manipulated in study 2b, a manipulation check was performed to test whether these variables had the intended effect. An independent sample

t-test showed that participants perceived NFH to be significantly higher in high NFH scenarios (M = 3.79) than in low NFH scenarios (M = 1.37), indicating that the manipulation of NFH was effective.

Table 9 provides maculation check results.

Effect on VOR. I performed an independent sample

t-test to examine whether the different levels of VOR can impact REC. The result provided support for the moderating effect of VOR. Specifically, as indicated in

Table 10, VOR significantly impacts participants’ willingness of engaging in reconciliation behaviors, such that participants were significantly more inclined to pursue reconciliation (M = 3.56) when in the high VOR condition, compared with the low VOR condition (M = 2.96).

Table 10 provides the

t-test results as well.

16. Study 2 Discussion

By using an experimental design, studies 2a and 2b provide additional support to the moderating effects of NFH and VOR on influencing participants’ willingness to initiate reconciliation. Specifically, as indicated in

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9 and

Table 10, participants’ willingness of pursuing REC is impacted by NFH and VOR, such that when experiencing abusive supervision, participants were more likely to reconcile the relationship with the abusive supervisor when they have a higher level of NFH. Furthermore, after engaging in workplace deviant behaviors (e.g., CWB-O) as a response to abusive supervision, participants were more likely to reconcile the relationship with the abusive supervisor when they have a higher level of VOR.

17. General Discussion

This paper offers several contributions. Firstly, building on the perspective of power distance, this paper moved beyond the prevailing theoretical framework built on the SET and extended extant abusive supervision literature by detailing the outcomes of workplace mistreatment over time. Currently, the SET is playing a major role in the workplace offense literature [

4] and many studies in this domain focus on victims’ reciprocating behaviors, leaving non-retaliatory responses notably underdeveloped. It is also noteworthy to explore the possibility of expediency, especially when mistreatment takes place between supervisors and subordinates. Specifically, in the workplace context, it is not always the case that people respond to supervisors’ mistreatment by engaging in negative reciprocating behaviors. Instead, due to the power distance between employees and their supervisors as well as employees’ willingness to maintain their organizational legitimacy, people may choose not to engage in negative reciprocating behaviors. Therefore, the choice of not engaging in reciprocating behaviors can be a type of expediency, which is a way to cope with supervisor-related mistreatment without negative reciprocating behaviors because these behaviors will impede career advancement in the future. This paper extended the research on employees’ expedient behaviors by examining the direct effect of abusive supervision on reconciliation, which contributed to identifying employees’ expediency-seeking behavior in the workplace context.

Secondly, this paper contributed to the research on employees’ coping strategies for abusive supervision by examining the role of deviant behaviors toward the organization (i.e., CWB-O). Specifically, as predicted, the results indicated that employees were more likely to engage in CWB-O after experiencing abusive supervision, confirming that employees engage in negative reciprocating behaviors toward their hiring organization after they consider they are mistreated by their supervisor. This result implied that employees would consider supervisors to represent and embody the organization they work for. Further, over time, employees’ deviant behaviors (e.g., CWB-O) following abusive supervision will make them feel it is normal and acceptable to engage in problematic workplace activities, and CWB-O engagement will make employees feel it is not necessary to normalize the relationship with abusive supervisor through reconciliation.

Last but not least, this paper contributed to abusive supervision literature by examining two factors that moderate employees’ coping behaviors that respond to abusive supervision. Specifically, employees are more likely to engage in reconciliation following CWB-O engagement when they perceive a higher level of VOR. In addition, employees are more likely to engage in reconciliation following abusive supervision when they perceive a higher level of NFH.

18. Theoretical Implications

This paper provides several theoretical implications that deserve discussion. The findings provided support for both the indirect effect and the direct effect of ASUP on reconciliation. Specifically, for the direct effect, in study 1, when it comes to abusive supervision, employees are likely to respond to mistreatment by repairing and normalizing the relationship with abusive supervisors. This result provided support to the idea that in the organizational context, due to power distance and individual legitimacy maintenance are still important factors that influence employees’ reciprocating behaviors. Results also indicated that employees’ NFH significantly moderates the positive relationship between abusive supervision and reconciliation, such that employees engage in a higher degree of REC following ASUP when they take group harmony seriously.

Study 2 provided some additional support for the moderating effect of NFH. For the indirect effect, despite previous studies that have shown that mistreatment within an organization evokes negative reciprocity towards those who are responsible for it [

14], study 1 revealed that employees who experience abusive supervision will reciprocate against the hiring organization. Furthermore, study 1 supported the idea of normalized deviation, such that over time, workplace deviant behaviors (e.g., CWB-O) make employees feel there is no need to reconcile with abusive supervisors. This result also suggests that CWB-O engagement makes reconciliation become an unobligated and unnecessary behavior.

These results, taken together, indicated (1) a positive relationship between abusive supervision to CWB-O, (2) a negative relationship between CWB-O and reconciliation, and (3) a negative indirect effect from abusive supervision to reconciliation through CWB-O. Despite the negative indirect effect, as indicated in

Table 5, the total effect was still positive, suggesting that abusive supervision generally leads to reconciliation over time. In addition, despite the finding of a negative relationship between CWB-O and REC, the results indicated that employees are more likely to reconcile following CWB-O engagement when they believe their relationships with abusive supervisors are valuable (i.e., VOR is high). Study 2 provided additional support to the moderating effect of VOR as well.

19. Practical Implications

Some practical implications deserve discussion as well. Firstly, organizations usually focus on the bright side of supervisors’ behaviors, such as influential supervision and supervisor effectiveness. However, it is also noteworthy to pay attention to the dark side of supervisor behaviors. Previous studies have revealed there is a cross-level “trickle-down” pressure [

8,

64], such that the pressure of pursuing higher business performance transfers from the organization to supervisors, and supervisors can further transfer it to individual employees through the behaviors that they consider to be effective supervision [

65]. However, part of what supervisors believe to be effective supervision might be interpreted by subordinates as abusive supervision. Therefore, organization leaders should scrutinize their behaviors and ensure their self-perceived effective supervision does not turn into abusive supervision.

Secondly, the direct effect of abusive supervision on reconciliation revealed that employees may engage in expediency-seeking behaviors to respond to workplace mistreatment. Although seeking expediency does not reflect justice restoration and problem-solving at the workplace, it might serve employees’ best interest when pursuing expediency instead of taking arduous and risky measures to reciprocate, due to power distance between supervisor and employee, employees’ resource dependence, and organization’s expectation of conformity. By keeping this in mind, organization leaders should note that the absence of negative reciprocating behaviors following abusive supervision does not mean that abusive supervision is not an issue, instead, they should note that negative reciprocation might occur in the future when power distance becomes smaller, or when employees feel they no longer depend on the abusive supervisor to achieve their career advancement. Furthermore, reconciliation is subject to the employees’ need for harmony, such that employees are more willing to initiate reconciliation when they consider harmony within the organization important.

Thirdly, the indirect effect revealed intricacies of the underlying mechanism, which would otherwise be difficult to reveal. Specifically, based on the results of indirect effect, over time, employees who experience abusive supervision will engage in CWB-O to respond, and CWB-O engagement makes employees less likely to reconcile with abusive supervisors. This result suggests that CWB-O engagement could inhibit the likelihood of reconciliation. Therefore, organization leaders should seek ways to minimize the occurrence of employee-initiated CWBs by demotivating employees to engage in CWBs and encouraging employees to “speak out” in the form of confidential channels [

66,

67], or at least provide opportunities to make employees “think twice” before engaging in CWBs.

Last but not least, from the business effectiveness perspective, knowledge and intelligence sharing among employees within an organization is an important factor that contributes to organizational development, and employees’ perceived emotional safety and trust are important foundations for employees to share knowledge and intelligence [

68]. However, as a toxic interpersonal activity, abusive supervision will impede knowledge and intelligence sharing because it depletes employees’ psychological resources and makes employees feel unsafe sharing their knowledge and intelligence. Therefore, business leaders should have an adequate level of emotional intelligence to control their behaviors and ensure employees have positive psychological conditions. Furthermore, since the context of this study is abusive supervision among office-based workers, and workers in the professional service industry, such as the management consulting field [

69], are part of the office-based workers. This study will provide support and guidance to working professionals in the management consulting field as well.

20. Limitations and Future Research

This paper is not without limitations. I would like to point out the following limitations, future research that will potentially address these limitations, and future directions that will expand the extant literature. Firstly, this paper was based on a lagged design and an experiment with manipulated variables, however, all data were reported from a single source. Future research should pay more attention to multi-source data, such as data from workers’ colleagues and preferably supervisors.

Secondly, this paper’s topic is about the dark side of organizational behaviors and socially undesirable behaviors, creating pressure for participants to honestly report their actual perceptions and reactions. Future research in this area should consider including observable or objective variables, such as employees’ performance appraisal records, number of turnovers, and days of sick leave per year so that the limitation of perceptual variables can be potentially addressed.

Thirdly, although study 2 was able to test the moderating effect of NFH and VOR by employing the independent sample t-test, the experiment in study 2 was based on hypothetical scenarios, such that participants only read hypothetical stories and provide the answer to survey questions. This type of experiment has been utilized in previous studies to examine how a manipulated factor influences the reactions to workplace mistreatment, however, people might behave in ways that are different from what they report, in other words, it is possible for people not to “walk the talk”. Therefore, it would be beneficial to examine the causal relationship by conducting behavior-based experiments.

Further, both study 1 and study 2 collected data from surveys, which created a common method variance (CMV). Study 1 attempted to decrease CMV by setting up a 2-week time interval between each survey and employed the ULMC approach to test CMV and received acceptable results, however, it would be more effective to decrease CMV if data can be collected from more than one format by using a combination of survey, behavioral observation, and interview in future research.

Last but not least, human resource challenges in today’s business environment should be considered in future research. For example, many organizations are negatively impacted by labor shortages and great resignation. These challenges make it necessary for companies to rethink abusive supervision and other forms of workplace mistreatment, such as bullying and harassment because employee turnover will keep increasing if a company cannot solve issues related to workplace mistreatment. Future work should focus on approaches to prevent abusive supervision from occurring in the workplace as abusive supervision will jeopardize employees’ physiological and psychological well-being.

21. Conclusions

Abusive supervision has been found to beget employee-related issues. This paper moved beyond the prevalent SET perspective and explicated a moderated mediation model that detailed employees’ reactions to abusive supervision. Specifically, I found employees are likely to reconcile with their abusive supervisors because of the motivation of seeking expediency and pursuing future rewards. Meanwhile, I found after engaging in workplace deviant behaviors, employees are less likely to reconcile with their abusive supervisor. Furthermore, employees’ perceived value of the relationship with the supervisor and their need for harmony influence their reactions to abusive supervision.