Developing Women’s Authenticity in Leadership

Abstract

1. Problem, Purpose, and Research Questions

- How do women perceive developing authenticity in leadership?

- How, if at all, do women experience authenticity development through attending a women’s leadership development program?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Developing Authenticity in Leadership

2.2. Applying Authentic Leadership to Women Leaders

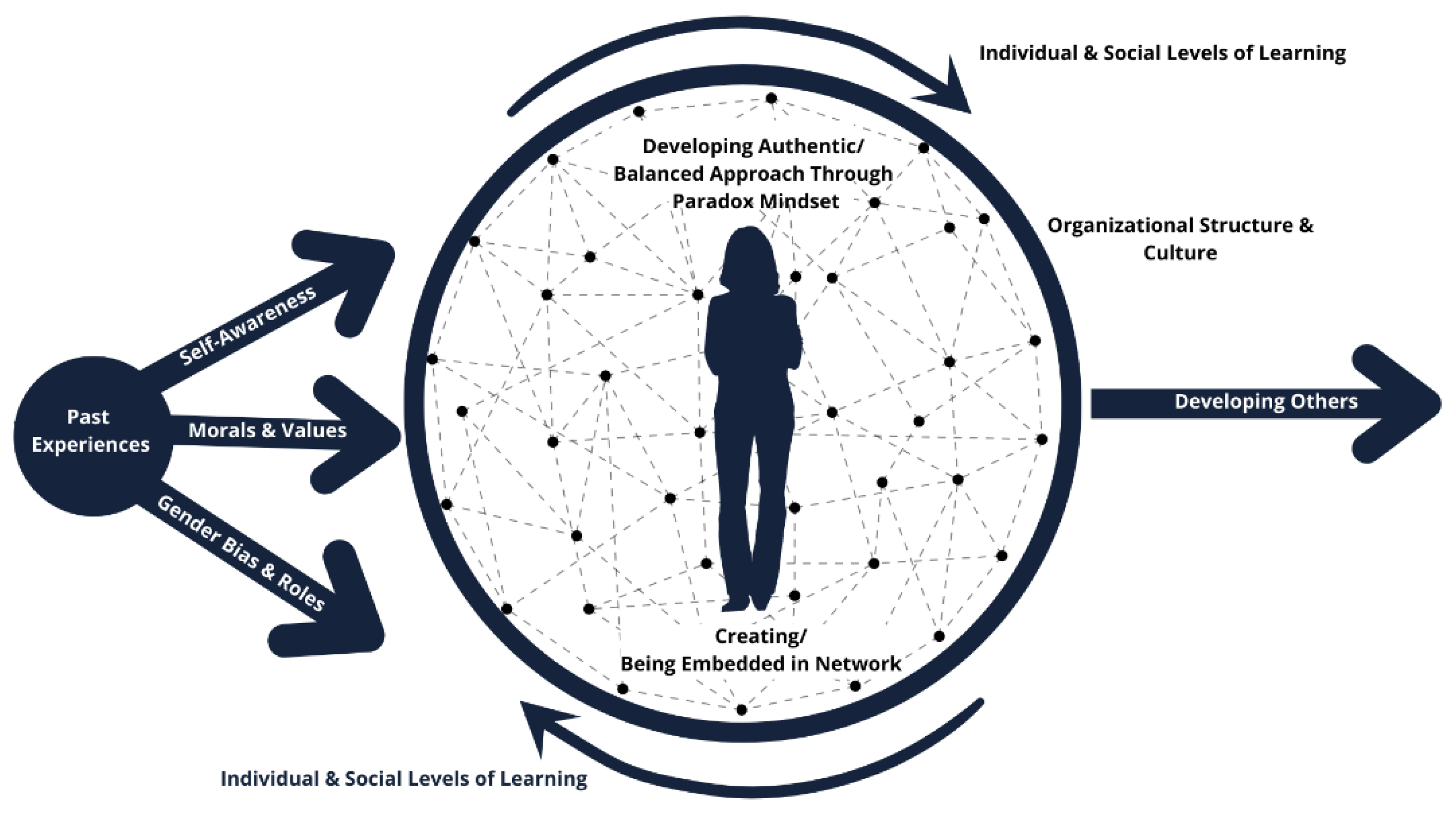

2.3. Women’s Authentic Leadership Development

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

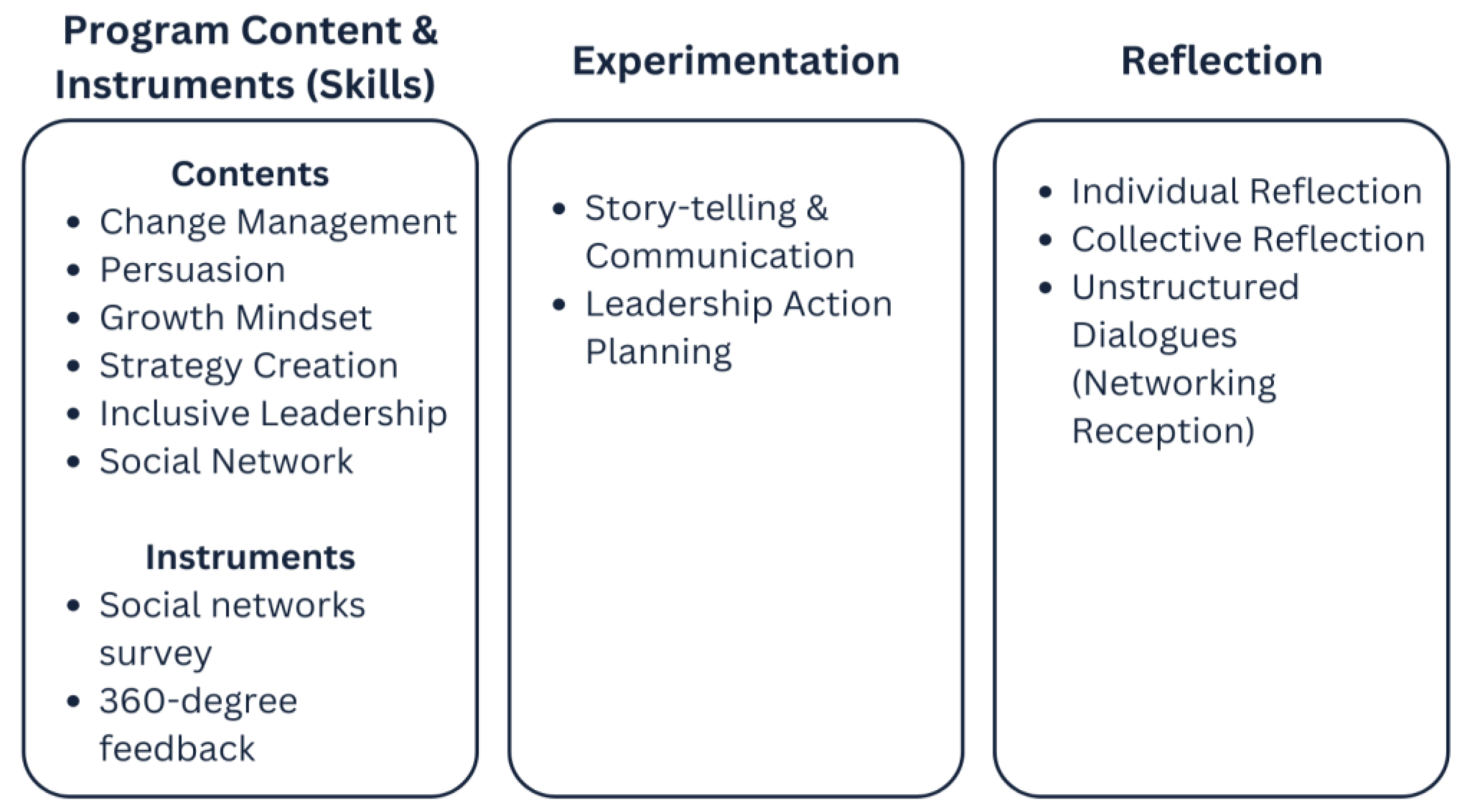

3.2. Women in Leadership Development Program Context

3.3. Data Analysis Process

4. Results

4.1. Women’s Authentic Leadership Development

4.2. Learning to Lead

4.3. Gendered Performance of Leadership

4.4. Program Evaluation and Training

4.4.1. Developing Self

4.4.2. Developing Others

4.4.3. Creating/Being Embedded in Network

5. Discussion

5.1. How Do Women Perceive Developing Authenticity in Leadership?

5.2. How Do Women Experience Authenticity Development through the Women’s Leadership Development Program?

6. Implications for Future Research and Practice

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Seo, G.; Huang, W.; Han, S.C. Conceptual review of underrepresentation of women in senior leadership positions from a perspective of gendered social status in the Workplace: Implication for HRD research and practice. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2017, 16, 35–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakradhar, S. Boardroom bound: Efforts to bring more women into biomed industry’s top ranks. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Gender Gap Report. Global Gender Gap Report Insight Report. World Econ. Forum 2022. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gender-gap-report-2022/ (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Adame, C.; Caplliure, E.; Miquel, M. Work-life balance and firms: A matter of women? J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1379–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, F.; Baykal, E.; Abid, G. E-Leadership and teleworking in times of COVID-19 and beyond: What we know and where do we go. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 590271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, E.N.; Grande, S.; Nakamura, Y.T.; Pyle, L.; Shaw, G. The development and practice of authentic leadership: A cultural lens. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Cutcher, L.; Grant, D. Doing authenticity: The gendered construction of authentic leadership. Gend. Work. Organ. 2015, 22, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L.; Wernsing, T.S.; Peterson, S.J. Authentic leadership: Development and validation of a theory-based measure. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 89–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, M.M.; O’Neil, D.A. Authentic leadership: Application to women leaders. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eich, D. A grounded theory of high-quality leadership programs. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2008, 15, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillema, H.H. Authenticity in knowledge-productive learning: What drives knowledge construction in collaborative inquiry? Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2006, 9, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woerkom, M. The concept of critical reflection and its implications for human resource development. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2004, 6, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, L.; Parent, É. Developing authentic leadership within a training context: Three phenomena supporting the individual development process. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2015, 22, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, B.; Sims, P.; McLean, A.N.; Mayer, D. Discovering your authentic leadership. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 85, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Klepper, W.M.; Nakamura, Y.T. The Leadership Credo. Dev. Lead. 2012, 24–31. Available online: https://developingleadersquarterly.com/dlq-issue-008/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Diehl, A.B.; Dzubinski, L.M. Making the invisible visible: A cross-sector analysis of gender-based leadership barriers. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2016, 27, 181–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L. Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, J.; Ashman, I. Theorizing leadership authenticity: A Sartrean perspective. Leadership 2012, 8, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, S.M.; Luthans, F. Relationship between Entrepreneurs’ Psychological Capital and Their Authentic Leadership. J. Manag. Issues 2006, 18, 254–273. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.H. The Farther Reaches of Human Nature; Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, W.L.; Cogliser, C.C.; Davis, K.M.; Dickens, M.P. Authentic leadership: A review of the literature and research agenda. Leadersh. Q. 2011, 22, 1120–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kets de Vries, M.F.R.; Korotov, K. Creating transformational executive education programs. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2007, 6, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciporen, R. The role of personally transformative learning in leadership development: A case study. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2010, 17, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beechler, S.; Ciporen, R.; Yorks, L. Intersecting journeys in creating learning communities in executive education. Action Res. 2013, 11, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilies, R.; Morgeson, F.P.; Nahrgang, J.D. Authentic leadership and eudaemonic well-being: Understanding leader–follower outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 373–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, B.; Eilam, G. ‘What’s your story?’ A life-stories approach to authentic leadership development. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 395–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrowe, R.T. Authentic leadership and the narrative self. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 419–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neider, L.L.; Schriesheim, C.A. The authentic leadership inventory (ALI): Development and empirical tests. Leadersh. Q. 2011, 22, 1146–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorks, L.; Beechler, S.; Ciporen, R. Enhancing the impact of an open-enrollment executive program through assessment. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2007, 6, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltbia, T.E.; Marsick, V.J.; Ghosh, R. Executive and organizational coaching: A review of insights drawn from literature to inform HRD practice. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2014, 16, 161–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mälkki, K. Rethinking disorienting dilemmas within real-life crises: The role of reflection in negotiating emotionally chaotic experiences. Adult Educ. Q. 2012, 62, 207–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Gooty, J. Values, emotions, and authenticity: Will the real leader please stand up? Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbit, P.L. The role of self-reflection, emotional management of feedback, and self-regulation processes in self-directed leadership development. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2012, 11, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.D.; Scandura, T.A.; Schriesheim, C.A. Looking forward but learning from our past: Potential challenges to developing authentic leadership theory and authentic leaders. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D.A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B.; Baumgartner, L.M. Learning in Adulthood, 4th ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. Learning as transformation. In Learning to Think Like An Adult: Core Concepts of Transformation Theory; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Puente, S.; Crous, F.; Venter, A. The role of a positive trigger event in actioning authentic leadership development. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 5, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, L. Authentic leadership and mindfulness development through action learning. J. Manag. Psychol. 2016, 31, 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiersch, C.; Peters, J. Leadership from the inside out: Student leadership development within authentic leadership and servant leadership frameworks. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2017, 16, 148–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, S.; Peus, C.; Frey, D. Connectionism in action: Exploring the links between leader prototypes, leader gender, and perceptions of authentic leadership. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2018, 149, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debebe, G. Navigating the double bind: Transformations to balance contextual responsiveness and authenticity in women’s leadership development. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2017, 4, 1313543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H. Achieving relational authenticity in leadership: Does gender matter? Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Karau, S.J. Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychol. Rev. 2002, 109, 573–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilman, M.E. Gender stereotypes and workplace bias. Res. Organ. Behav. 2012, 32, 113–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, H. The Authenticity Paradox. Harvard Bus. Rev. 2015, 52–59. Available online: https://hbr.org/2015/01/the-authenticity-paradox (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Belenky, M.F.; Clinchy, B.M.; Goldberger, N.R.; Tarule, J.M. Women’s Ways of Knowing: The Development of Self, Voice, and Mind; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1986; Volume 15. [Google Scholar]

- Ely, R.J.; Ibarra, H.; Kolb, D.M. Taking gender into account: Theory and design for women’s leadership development programs. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2011, 10, 474–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gipson, A.N.; Pfaff, D.L.; Mendelsohn, D.B.; Catenacci, L.T.; Burke, W.W. Women and leadership: Selection, development, leadership style, and performance. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2017, 53, 32–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimball, T.D.; Reichard, R.J.; Chan, E.L. Women’s leader development programs: Current landscape and recommendations for future programs. J. Bus. Divers. 2021, 21, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ose, S.O. Using excel and word to structure qualitative data. J. Appl. Soc. 2016, 10, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brue, K.L.; Brue, S.A. Leadership role identity construction in women’s leadership development programs. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2018, 17, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Kark, R.; Meister, A.L. Paradox versus dilemma mindset: A theory of how women leaders navigate the tensions between agency and communion. Leadersh. Q. 2018, 29, 584–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, D.R.; DeChurch, L.A.; Braun, M.T.; Contractor, N.S. Social network approaches to leadership: An integrative conceptual review. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 597–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.T.; Yorks, L. The role of reflective practices in building social capital in organizations from an HRD perspective. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2011, 10, 222–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanton, C.R. Shaping leadership culture to sustain future generations of women leaders. J. Leadersh. Account. Ethics 2015, 12, 92–112. [Google Scholar]

- Miron-Spektor, E.; Ingram, A.; Keller, J.; Smith, W.K.; Lewis, M.W. Microfoundations of organizational paradox: The problem is how we think about the problem. Acad. Manag. J. 2018, 61, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, A.; Kahrens, M.; Mouzughi, Y.; Eomois, E. A female leadership competency framework from the perspective of male leaders. Gend. Manag. 2018, 33, 138–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookfield, S.D.; Preskill, S. Discussion as a Way of Teaching: Tools and Techniques for Democratic Classrooms; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| Participant | Title | Function | Industry | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anna | President | General Management | Higher Education | US |

| Nora | Vice President | Partnership Management | Pharmaceuticals | US |

| Roberta | Producer | Information Technology | Media | Australia |

| Sally | Executive Director | General Management | Manufacturing | India |

| Naomi | Director/Owner | General Management | Chemicals | India |

| Emma | Strategic HR and Scientist | Human Resources | Research and Development | Austria |

| Yoly | Senior Director | Information Technology | Media | US |

| Themes | Sub-Themes | Research Question |

|---|---|---|

| Learning to Lead |

| Q1. How do women perceive developing authenticity in leadership? |

| Gendered Performance of Leadership |

| Q1. How do women perceive developing authenticity in leadership? |

| Program Evaluation |

| Q2. How, if at all, do women experience authentic leadership development during a women’s leadership development program? |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nakamura, Y.T.; Hinshaw, J.; Burns, R. Developing Women’s Authenticity in Leadership. Merits 2022, 2, 408-426. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits2040029

Nakamura YT, Hinshaw J, Burns R. Developing Women’s Authenticity in Leadership. Merits. 2022; 2(4):408-426. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits2040029

Chicago/Turabian StyleNakamura, Yoshie Tomozumi, Jessica Hinshaw, and Rebecca Burns. 2022. "Developing Women’s Authenticity in Leadership" Merits 2, no. 4: 408-426. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits2040029

APA StyleNakamura, Y. T., Hinshaw, J., & Burns, R. (2022). Developing Women’s Authenticity in Leadership. Merits, 2(4), 408-426. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits2040029