A Note on Computational Characterization of Dy@C82: Dopant for Solar Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Calculations

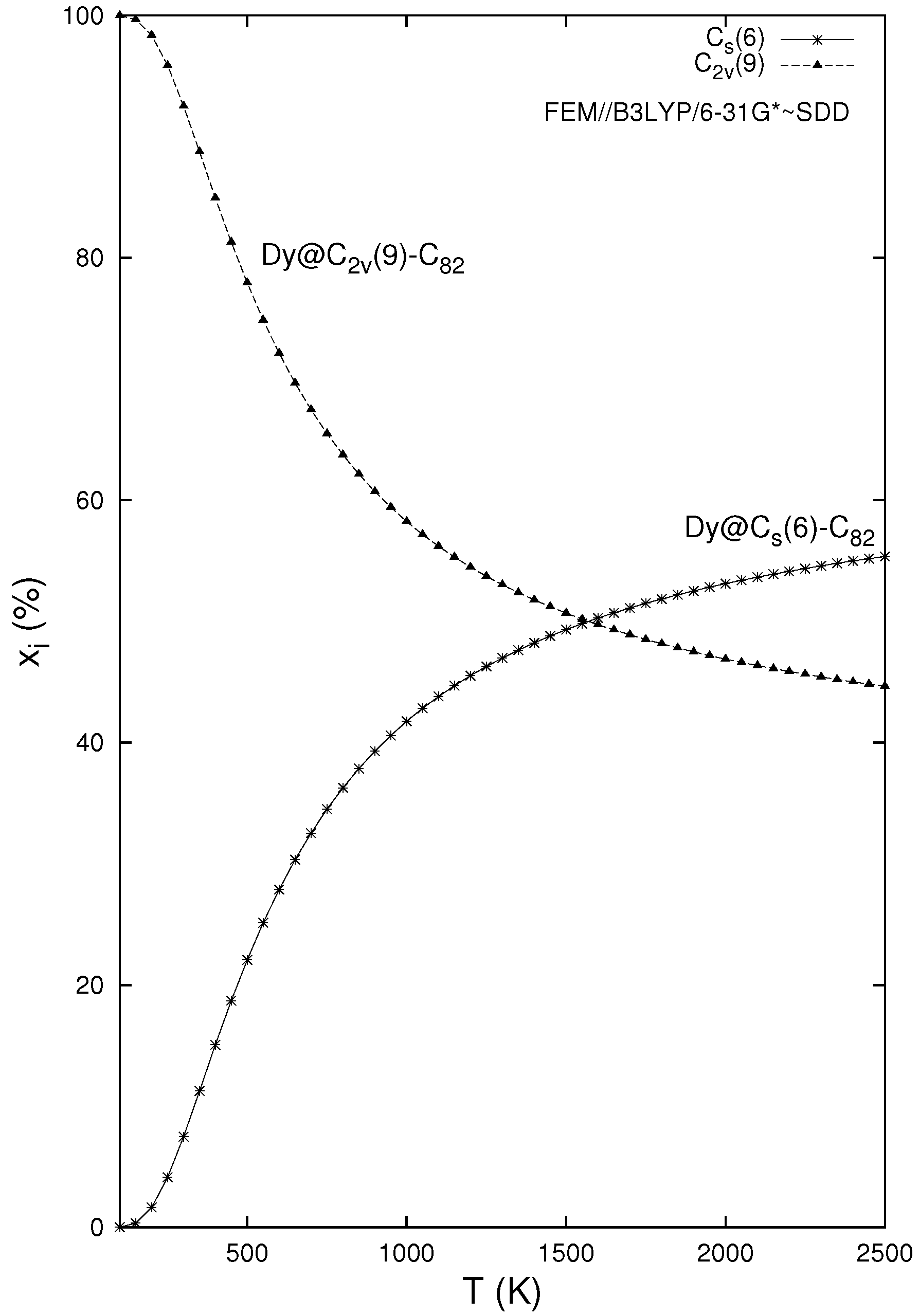

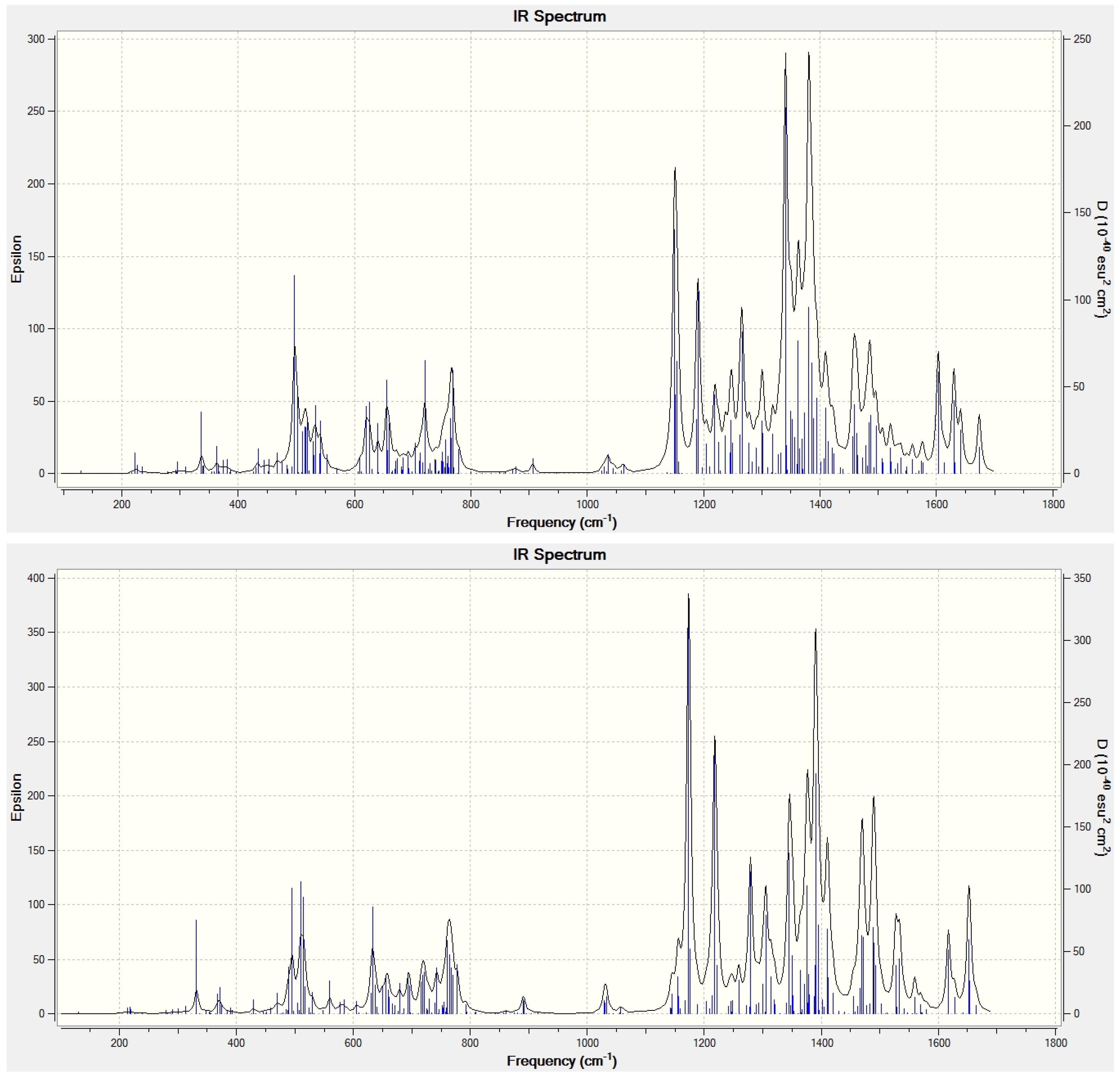

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, S.; Fan, L.; Yang, S. Preparation, characterization, and photoelectrochemistry of Langmuir-Blodgett films of the endohedral metallofullerene Dy@C82 mixed with metallophthalocyanines. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 8403–8411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Fan, L.; Yang, S. Langmuir–Blodgett films of poly(3-hexylthiophene) doped with the endohedral metallofullerene Dy@C82: Preparation, characterization, and application in photoelectrochemical cells. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 4394–4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Fan, L.; Yang, Y. Significantly enhanced photocurrent efficiency of a poly(3-hexylthiophene) photoelectrochemical device by doping with the endohedral metallofullerene Dy@C82. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004, 388, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E.A. Fullerene thin films as photovoltaic material. In Nanostructured Materials for Solar Energy Conversion; Soga, T., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 361–443. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, X.; Yu, P.; Shen, W.; Hu, S.; Akasaka, T.; Lu, X. Er@C82 as a bifunctional additive to the spiro-OMeTAD hole transport layer for improving performance and stability of perovskite solar cells. Sol. RRL 2021, 5, 2100463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Uhlík, F.; Hu, S.; Akasaka, T.; Lu, X.; Adamowicz, L. Calculated isomeric populations of Er@C82. Fullerenes Nanotub. Carbon Nanostruct. 2024, 32, 986–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumyatov, A.V.; Troshin, P.A. A review on fullerene derivatives with reduced electron affinity as acceptor materials for organic solar cells. Energies 2023, 16, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iida, S.; Kubozono, Y.; Slovokhotov, Y.; Takabayashi, Y.; Kanbara, T.; Fukunaga, T.; Fujiki, S.; Emura, S.; Kashino, S. Structure and electronic properties of Dy@C82 studied by UV–VIS absorption, X-ray powder diffraction and XAFS. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2001, 338, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Takabayashi, Y.; Haruyama, Y.; Rikiishi, Y.; Hosokawa, T.; Shibata, K.; Kubozono, Y. Preferred location of the Dy ion in the minor isomer of Dy@C82 determined by Dy LIII-edge EXAFS. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004, 388, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Xenogiannopoulou, E.; Couris, S.; Koudoumas, E.; Tagmatarchis, N.; Inoue, T.; Shinohara, H. Nonlinear optical response of some isomerically pure higher fullerenes and their corresponding endohedral metallofullerene derivatives: C82–C2v, Dy@C82(I), Dy2@C82(I), C92–C2 and Er2@C92(IV). Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004, 394, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Fan, L.; Liu, D.; Sung, H.H.Y.; Williams, I.D.; Yang, S.; Tan, K.; Lu, X. Synthesis of a Dy@C82 derivative bearing a single phosphorus substituent via a zwitterion approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 10636–10637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaura, R.; Okimoto, H.; Shinohara, H.; Nakamura, T.; Osawa, H. Magnetism of the endohedral metallofullerenes M@C82 (M = Gd, Dy) and the corresponding nanoscale peapods: Synchrotron soft x-ray magnetic circular dichroism and density-functional theory calculations. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 76, 172409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Fortea, A.; Balch, A.L.; Poblet, J.M. Endohedral metallofullerenes: A unique host-guest association. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 3551–3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, A.A.; Yang, S.; Dunsch, L. Endohedral fullerenes. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5989–6113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareev, I.E.; Nekrasov, V.M.; Dutlov, A.E.; Bubnov, V.P.; Martynenko, V.M.; Laukhina, E.E.; Veciana, J.; Rovira, C. Determination of molar extinction coefficients for endohedral metallofullerene Dy@C82(C2v). Russ. Chem. Bull. (Int. Ed.) 2016, 65, 2421–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Barbosa, M.F.S.; Alfonsov, A.; Rosenkranz, M.; Israel, N.; Büchner, B.; Avdoshenko, S.M.; Liu, F.; Popov, A.A. Thirty years of hide-and-seek: Capturing abundant but elusive MIII@C3v(8)-C82 isomer, and the study of magnetic anisotropy induced in Dy3+ ion by the fullerene π-ligand. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 25328–25342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slanina, Z.; Uhlík, F.; Feng, L.; Adamowicz, L. Calculated relative populations of Sm@C82 isomers. Fullerenes Nanotub. Carbon Nanostruct. 2018, 26, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Lee, S.-L.; Kobayashi, K.; Nagase, S. AM1 computed thermal effects within the nine isolated-pentagon-rule isomers of C82. J. Mol. Struct. (Theochem) 1995, 339, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishibori, E.; Takata, M.; Sakata, M.; Inakuma, M.; Shinohara, H. Determination of the cage structure of Sc@C82 by synchrotron powder diffraction. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1998, 298, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Kobayashi, K.; Nagase, S. Ca@C82 isomers: Computed temperature dependency of relative concentrations. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 120, 3397–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slanina, Z.; Kobayashi, K.; Nagase, S. Computed temperature development of the relative stabilities of La@C82 isomers. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004, 388, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Slanina, Z.; Mizorogi, N.; Lu, X.; Nagase, S.; Olmstead, M.M.; Balch, A.L.; Akasaka, T. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction study of three Yb@C82 isomers cocrystallized with Ni-II(octaethylporphyrin). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 18772–18778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Hao, Y.; Slanina, Z.; Gu, Z.; Shi, Z.; Uhlík, F.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, L. Popular C82 fullerene cage encapsulating a divalent metal ion Sm2+: Structure and electrochemistry. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 2103–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Lee, S.-L.; Adamowicz, L. C80, C86, C88: Semiempirical and ab initio SCF calculations. Int. J. Quantum. Chem. 1997, 63, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Uhlík, F. Temperature dependence of the Gibbs energy ordering of isomers of Cl2O2. J. Phys. Chem. 1991, 95, 5432–5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Zhao, X.; Lee, S.-L.; Ōsawa, E. C90 Temperature effects on relative stabilities of the IPR isomers. Chem. Phys. 1997, 219, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlík, F.; Slanina, Z.; Ōsawa, E. C78 IPR fullerenes: Computed B3LYP/6-31G*//HF/3-21G temperature-dependent relative concentrations. Eur. Phys. J. D 2001, 16, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Zhao, X.; Uhlík, F.; Lee, S.-L.; Adamowicz, L. Computing enthalpy-entropy interplay for isomeric fullerenes. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2004, 99, 640–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Lee, S.-L.; Adamowicz, L.; Uhlík, F.; Nagase, S. Computed structure and energetics of La@C60. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2005, 104, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Lee, S.-L.; Uhlík, F.; Adamowicz, L.; Nagase, S. Computing relative stabilities of metallofullerenes by Gibbs energy treatments. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2007, 117, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Morales-Martínez, R.; Zhang, X.; Yang, W.; Wang, Y.; Rodríguez-Fortea, A.; Poblet, J.M.; Feng, L.; Wang, S.; Chen, N. Unique four-electron metal-to-cage charge transfer of Th to a C82 fullerene cage: Complete structural characterization of Th@C3v(8)-C82. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 5110–5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Uhlík, F.; Nagase, S.; Akasaka, T.; Adamowicz, L.; Lu, X. Eu@C72: Computed comparable populations of two non-IPR isomers. Molecules 2017, 22, 1053. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, M.; Zhao, R.; Zhao, P.; Yuan, K.; Li, Q.; Zhao, X. Unmasking the optimal isomers of Ti2C84: Ti2C2@C82 Instead of Ti2C84. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 13148–13155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkley, J.S.; Pople, J.A.; Hehre, W.J. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. 21. Small split-valence basis sets for first-row elements. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 939–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.Y.; Dolg, M. Segmented contraction scheme for small-core lanthanide pseudopotential basis sets. J. Mol. Struct. (Theochem) 2002, 581, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becke, A.D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R.G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hehre, W.J.; Ditchfield, R.; Pople, J.A. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XII. Further extensions of Gaussian-type basis sets for use in molecular-orbital studies of organic-molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1972, 56, 2257–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, H.B.; McDouall, J.J.W. Do you have SCF stability and convergence problems? In Computational Advances in Organic Chemistry; Ögretir, C., Csizmadia, I.G., Eds.; Kluwer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1991; pp. 167–185. [Google Scholar]

- Slanina, Z.; Uhlík, F.; Adamowicz, L. Computations of model narrow nanotubes closed by fragments of smaller fullerenes and quasi-fullerenes. J. Mol. Graph. Mod. 2003, 21, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A.; et al. Gaussian 09, Rev. C.01; Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Slanina, Z. Equilibrium isomeric mixtures: Potential energy hypersurfaces as originators of the description of the overall thermodynamics and kinetics. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1987, 6, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z. A Program for determination of composition and thermodynamics of the ideal gas-phase equilibrium isomeric mixtures. Comput. Chem. 1989, 13, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Uhlík, F.; Zerner, M.C. isomeric structures: Relative stabilities at high temperatures. Rev. Roum. Chim. 1991, 36, 965–974. [Google Scholar]

- Slanina, Z.; Adamowicz, L. On relative stabilities of dodecahedron-shaped and bowl-shaped structures of C20. Thermochim. Acta 1992, 205, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, R.J.; Saunders, M. Transmutation of fullerenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 3044–3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slanina, Z.; Zhao, X.; Uhlík, F.; Ozawa, M.; Osawa, E. Computational modelling of the metal and other elemental catalysis in the Stone-Wales fullerene rearrangements. J. Organomet. Chem. 2000, 599, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Adamowicz, L.; Kobayashi, K.; Nagase, S. Gibbs energy-based treatment of metallofullerenes: Ca@C72, Ca@C74, Ca@C82, and La@C82. Mol. Simul. 2005, 31, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akasaka, T.; Nagase, S.; Kobayashi, K.; Walchli, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Funasaka, H.; Kako, M.; Hoshino, T.; Erata, T. 13C and 139La NMR studies of La2@C80: First evidence for circular motion of metal atoms in endohedral dimetallofullerenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1997, 36, 1643–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K.; Nagase, S.; Maeda, Y.; Wakahara, T.; Akasaka, T. La2@C80: Is the circular motion of two La atoms controllable by exohedral addition? Chem. Phys. Lett. 2003, 374, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z. Contemporary Theory of Chemical Isomerism; Academia: Prague, Czech Republic; D. Reidel Publishing Company: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1986; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Slanina, Z.; Uhlík, F.; Bao, L.; Akasaka, T.; Lu, X.; Adamowicz, L. Calculated relative populations for the Eu@C82 isomers. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2019, 726, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takata, M.; Nishibori, E.; Sakata, M.; Shinohara, H. Charge density level structures of endohedral metallofullerenes determined by synchrotron radiation powder method. New Diam. Front. Carb. Technol. 2002, 12, 271–286. [Google Scholar]

- Hehre, W.J. A Guide to Molecular Mechanics and Quantum Chemical Calculations; Wavefunction: Irvine, CA, USA, 2003; p. 435. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, F. Introduction to Computational Chemistry; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2017; p. 319. [Google Scholar]

- Campanera, J.M.; Bo, C.; Poblet, J.M. General rule for the stabilization of fullerene cages encapsulating trimetallic nitride templates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 7230–7233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Uhlík, F.; Pan, C.; Akasaka, T.; Lu, X.; Adamowicz, L. Computed stabilization for a giant fullerene endohedral: Y2C2@C1(1660)-C108. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2018, 710, 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Uhlík, F.; Lee, S.-L.; Nagase, S. Structural and bonding features of Z@C82 (Z = Al, Sc, Y, La) endohedrals. J. Comput. Meth. Sci. Eng. 2010, 10, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Uhlík, F.; Lee, S.-L.; Suzuki, M.; Lu, X.; Mizorogi, N.; Nagase, S.; Akasaka, T. Calculated temperature development of the relative stabilities of Yb@C82 isomers. Fuller. Nanotub. Car. Nanostruct. 2014, 22, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Uhlík, F.; Shen, W.; Akasaka, T.; Lu, X.; Adamowicz, L. Calculations of the relative populations of Lu@C82 isomers. Fullerenes Nanotub. Carbon Nanostruct. 2019, 27, 710–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Uhlík, F.; Akasaka, T.; Lu, X.; Adamowicz, L. Calculated relative thermodynamic stabilities of the Gd@C82 isomers. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2021, 10, 071013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.Y.; Morales-Martínez, R.; Zhuang, J.X.; Yao, Y.R.; Wang, Y.F.; Feng, L.; Poblet, J.M.; Rodríguez-Fortea, A.; Chen, N. Synthesis and characterization of two isomers of Th@C82: Th@C2v(9)-C82 and Th@C2(5)-C82. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 11496–11502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Uhlík, F.; Feng, L.; Adamowicz, L. Ho@C82 metallofullerene: Calculated isomeric composition. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 053018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, W.; Curioni, A. Freedom and constraints of a metal atom encapsulated in fullerene cages. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 834–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, A.A.; Dunsch, L. Bonding in endohedral metallofullerenes as studied by quantum theory of atoms in molecules. Chem. Eur. J. 2009, 15, 9707–9729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slanina, Z.; Uhlík, F.; Lee, S.-L.; Adamowicz, L.; Akasaka, T.; Nagase, S. Computed stabilities in metallofullerene series: Al@C82, Sc@C82, Y@C82, and La@C82. Int. J. Quant. Chem. 2011, 111, 2712–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yu, M.; Jin, H.; Liu, Z.; Yao, M.; Liu, B.; Olmstead, M.M.; Balch, A.L. Isolation of three isomers of Sm@C84 and X-ray crystallographic characterization of Sm@D3d(19)-84 and Sm@C2(13)-C84. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 5331–5338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Feng, L.; Xu, W.; Gu, Z.; Hu, Z.; Shi, Z.; Slanina, Z.; Uhlík, F. Sm@C2v(19138)-C76: A non-IPR cage stabilized by a divalent metal ion. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 4243–4248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.; Tang, Q.; Li, X.; Zhang, M.; Wan, Y.; Feng, L.; Chen, N.; Slanina, Z.; Adamowicz, L.; Uhlík, F. Isomeric Sc2O@C78 related by a single-step Stone–Wales transformation: Key links in an unprecedented fullerene formation pathway. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 11354–11361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jehlička, J.; Svatoš, A.; Frank, O.; Uhlík, F. Evidence for fullerenes in solid bitumen from pillow lavas of proterozoic age from Mítov (Bohemian Massif, Czech Republic). Geochem. Cosmochem. Acta 2003, 67, 1495–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y.; Shi, Z.; Zhou, X.; Gu, Z. Different extraction behaviors between divalent and trivalent endohedral metallofullerenes. Chem. Mater. 2004, 16, 1704–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, Y.; Tsuchiya, T.; Kikuchi, T.; Nikawa, H.; Yang, T.; Zhao, X.; Slanina, Z.; Suzuki, M.; Yamada, M.; Lian, Y.; et al. Effective derivatization and extraction of insoluble missing lanthanum metallofullerenes La@C2n (n = 36–38) with iodobenzene. Carbon 2016, 98, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Uhlík, F.; Lee, S.-L.; Adamowicz, L.; Nagase, S. Computations of endohedral fullerenes: The Gibbs energy treatment. J. Comput. Meth. Sci. Engn. 2006, 6, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Uhlík, F.; Akasaka, T.; Lu, X.; Adamowicz, L. Theoretical studies of non-metal endohedral fullerenes. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Bi, C.; Wang, D.; Huang, J. The functions of fullerenes in hybrid perovskite solar cells. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 782–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, T.; Shimada, T.; Suenaga, K.; Ohno, Y.; Mizutani, T.; Lee, J.; Kuk, Y.; Shinohara, H. Electronic properties of Gd@C82 metallofullerene peapods: (Gd@C82)n@SWNTs. Appl. Phys. A 2003, 76, 475–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.K.; Wang, C.; Zhang, M.H.; Bai, Z.B.; Xie, F.F.; Tan, Y.Z.; Guo, Y.L.; Hu, K.J.; Cao, L.; Zhang, S.; et al. A Gd@C82 single-molecule electret. Nat. Nanotech. 2020, 15, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.-S.; An, M.-W.; Chen, J.-M.; Xing, Z.; Chen, Z.-C.; Deng, L.-L.; Tian, H.-R.; Yun, D.-Q.; Xie, S.-Y.; Zheng, L.-S. Radiation-processed perovskite solar cells with fullerene-enhanced performance and stability. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2021, 2, 100646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leenaerts, O.; Partoens, B.; Peeters, F.M. Water on graphene: Hydrophobicity and dipole moment using density functional theory. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 79, 235440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rašović, I. Water-soluble fullerenes for medical applications. Mater. Sci. Tech. 2017, 33, 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bologna, F.; Mattioli, E.J.; Bottoni, A.; Zerbetto, F.; Calvaresi, M. Interactions between endohedral metallofullerenes and proteins: The Gd@C60–lysozyme model. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 13782–13789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Zhao, C.; Nie, M.; Wang, C.; Wang, T. Changing the hydrophobic MOF pores through encapsulating fullerene C60 and metallofullerene Sc3C2@C80. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 6265–6269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebowski, J.; Litwinienko, G. Metallofullerenols in biomedical applications. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 238, 114481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matnazarova, S.; Matyakubov, N.; Khalilov, U.; Yusupov, M. Influence of encapsulated transition metal atoms on the hydrophilic properties of C84 fullerene: A computational study. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2025, 869, 142067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueorguiev, G.K.; Stafström, S.; Hultman, L. Nano-wire formation by self-assembly of silicon-metal cage-like molecules. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2008, 458, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Uhlík, F.; Lee, S.-L.; Akasaka, T.; Nagase, S. Stability computations for fullerenes and metallofullerenes. In Handbook of Carbon Nano Materials; D’Souza, F., Kadish, K.M., Eds.; Materials and Fundamental Applications; World Scientific Publishing Co.: Singapore, 2012; Volume 4, pp. 381–429. [Google Scholar]

- An, D.-Y.; Su, J.-G.; Li, C.-H.; Li, J.-Y. Computational studies on the interactions of nanomaterials with proteins and their impacts. Chin. Phys. B 2015, 24, 120504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiuk, V.A.; Tahuilan-Anguiano, D.E. Complexation of free-base and 3d transition metal(II) phthalocyanines with endohedral fullerene Sc3N@C80. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2019, 722, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahuilan-Anguiano, D.E.; Basiuk, V.A. Complexation of free-base and 3d transition metal(II) phthalocyanines with endohedral fullerenes H@C60, H2@C60 and He@C60: The effect of encapsulated species. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2021, 118, 108510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlík, F.; Slanina, Z.; Bao, L.; Akasaka, T.; Lu, X.; Adamowicz, L. Eu@C88 isomers: Calculated relative populations. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 101008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhao, R.; Dang, J.; Zhao, X. Theoretical study on the stabilities, electronic structures, and reaction and formation mechanisms of fullerenes and endohedral metallofullerenes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 471, 214762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Uhlík, F.; Adamowicz, L. Theoretical predictions of fullerene stabilities. In Handbook of Fullerene Science and Technology; Lu, X., Akasaka, T., Slanina, Z., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 111–179. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, A.; Kaur, R.; Guldi, D.M. Merging Carbon Nanostructures with Porphyrins. In Handbook of Fullerene Science and Technology; Lu, X., Akasaka, T., Slanina, Z., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 219–264. [Google Scholar]

- Basiuk, V.A.; Wu, Y.F.; Prezhdo, O.V.; Basiuk, E.V. Lanthanide atoms induce strong graphene sheet distortion when adsorbed on Stone-Wales defects. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 9706–9713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gra̧dzka, E. Electrocatalytic properties of fullerene-based materials. In NanoCarbon: A Wonder Material for Energy Applications; Gupta, R.K., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2024; Volume 1, pp. 199–218. [Google Scholar]

| Species | /kcal·mol−1 | /kcal·mol−1 |

|---|---|---|

| a | 1.77 | 1.91 |

| a | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Species | /Å | p/Debye | /cm−1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c | 2.480 | 2.018 | 0.801 | 27.5 |

| c | 2.513 | 2.011 | 1.345 | 18.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Slanina, Z.; Uhlík, F.; Akasaka, T.; Lu, X.; Adamowicz, L. A Note on Computational Characterization of Dy@C82: Dopant for Solar Cells. Micro 2025, 5, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/micro5040049

Slanina Z, Uhlík F, Akasaka T, Lu X, Adamowicz L. A Note on Computational Characterization of Dy@C82: Dopant for Solar Cells. Micro. 2025; 5(4):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/micro5040049

Chicago/Turabian StyleSlanina, Zdeněk, Filip Uhlík, Takeshi Akasaka, Xing Lu, and Ludwik Adamowicz. 2025. "A Note on Computational Characterization of Dy@C82: Dopant for Solar Cells" Micro 5, no. 4: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/micro5040049

APA StyleSlanina, Z., Uhlík, F., Akasaka, T., Lu, X., & Adamowicz, L. (2025). A Note on Computational Characterization of Dy@C82: Dopant for Solar Cells. Micro, 5(4), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/micro5040049