Performance Analysis of Seawater Desalination Using Reverse Osmosis and Energy Recovery Devices in Nouadhibou

Abstract

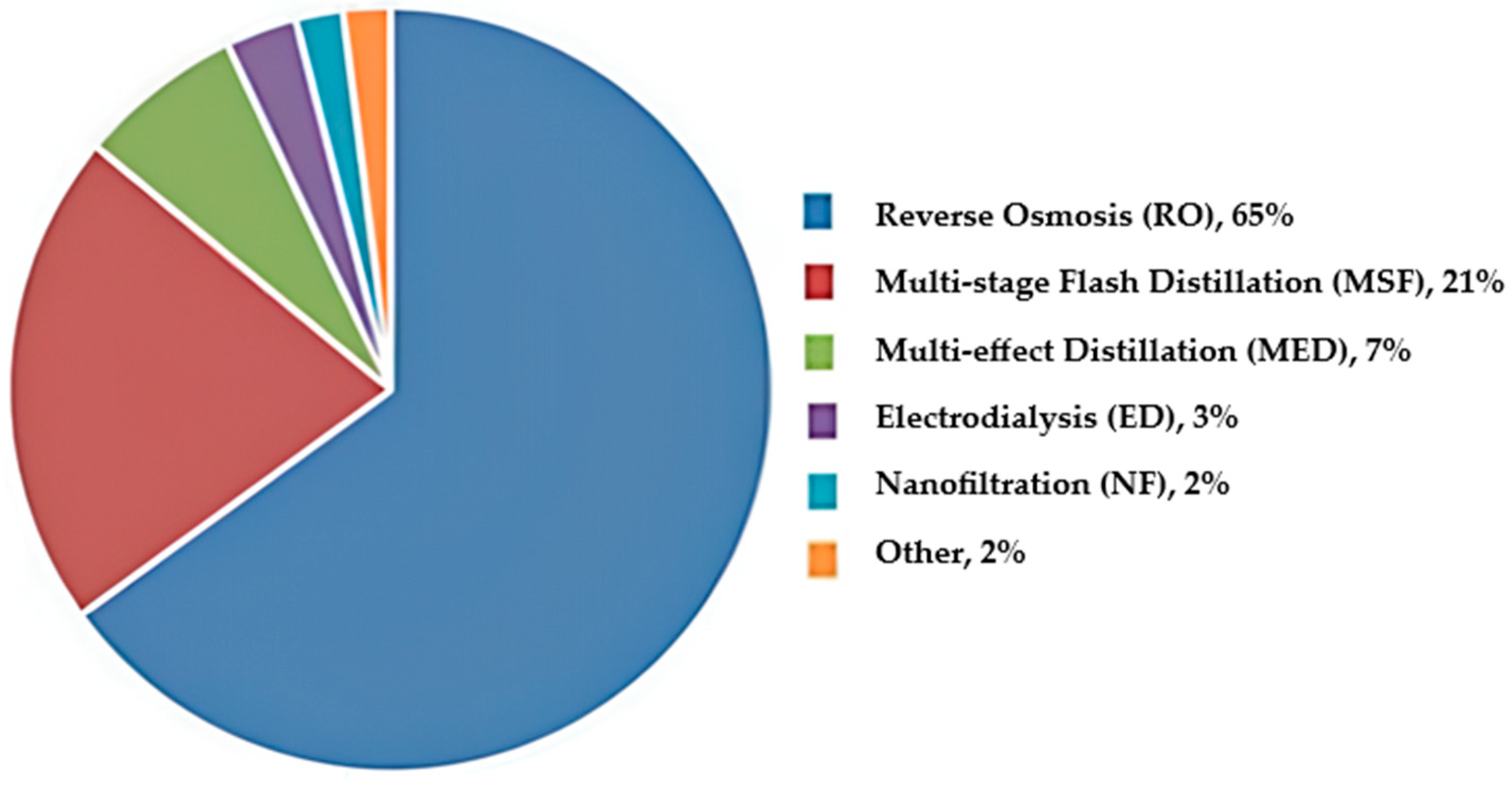

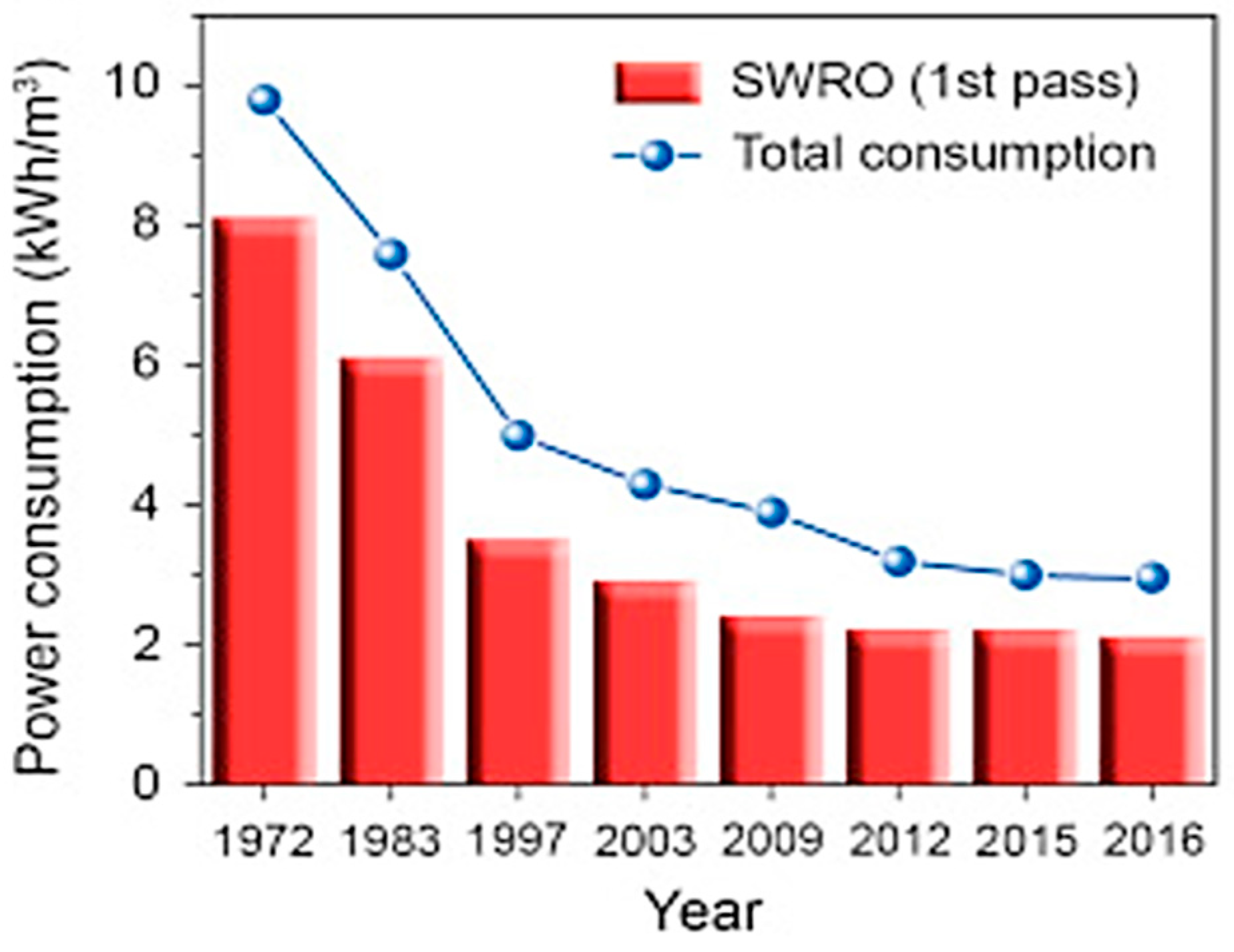

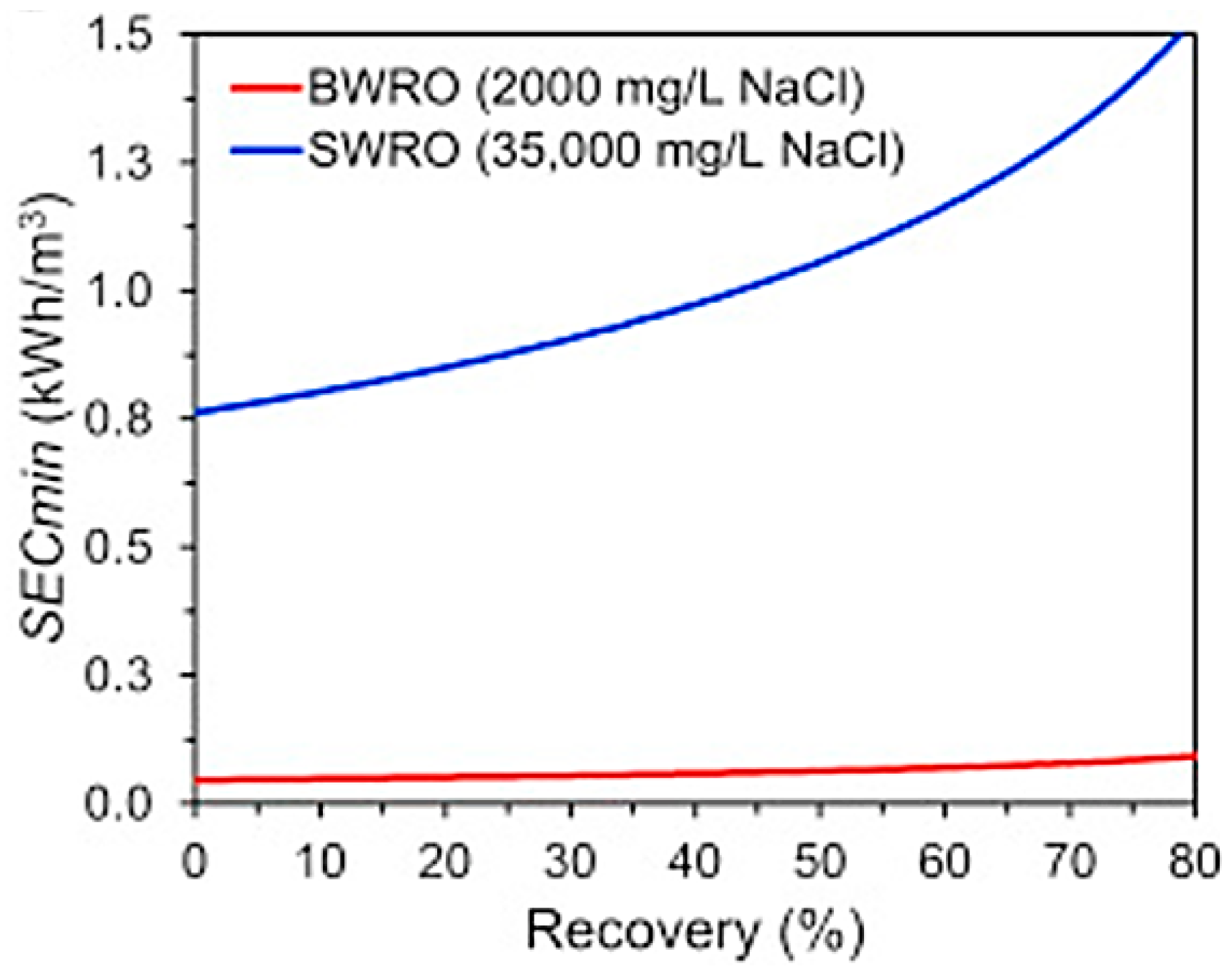

1. Introduction

2. Energy Recovery Devices

- Pressure exchangers (PEXs): these reduce the energy consumption of the HP-pump unit, due to the high efficiency of the PEX by transferring the concentrate pressure at the outlet of the membrane system to the raw feed water [27].

- These isobaric ERDs have an operating efficiency of up 98% [28]. This technique is widely used in large-scale reverse osmosis (SWRO) desalination plants [27]. Pressure exchangers provide similar or slightly higher energy recovery efficiency, often with lower capital and maintenance costs. Their compact and modular design makes them suitable for systems with space limitations, and their simpler mechanical components contribute to higher reliability and easier maintenance [27,28].

3. Description of the Studied Plant

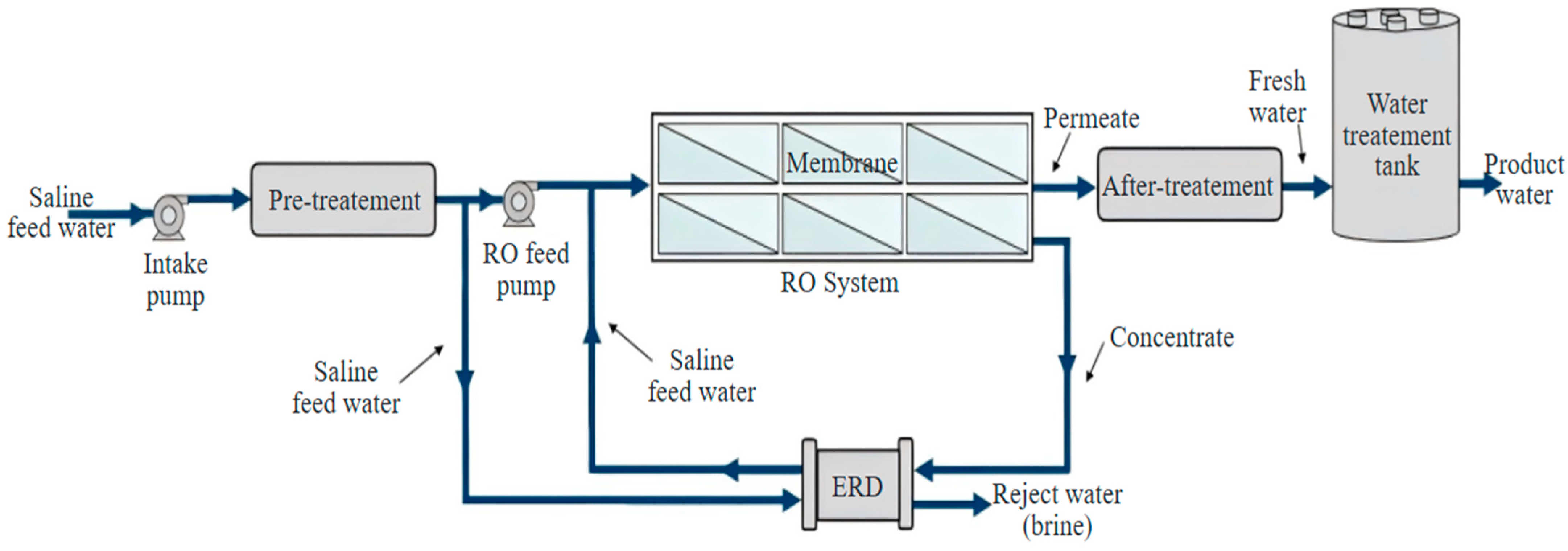

4. System Modeling and Mathematical Formulation

4.1. RO Mathematical Model

- Permeate, which passes through the membrane;

- Concentrate (retentate), which is retained by the semi-permeable film; contains the rejected salts and other particles.

4.2. ERDs Mathematical

4.2.1. Splitter Unit

4.2.2. High Pressure Pump Unit

4.2.3. Mixer Unit

4.2.4. Booster Pump Unit

4.2.5. Pressure Exchanger Unit

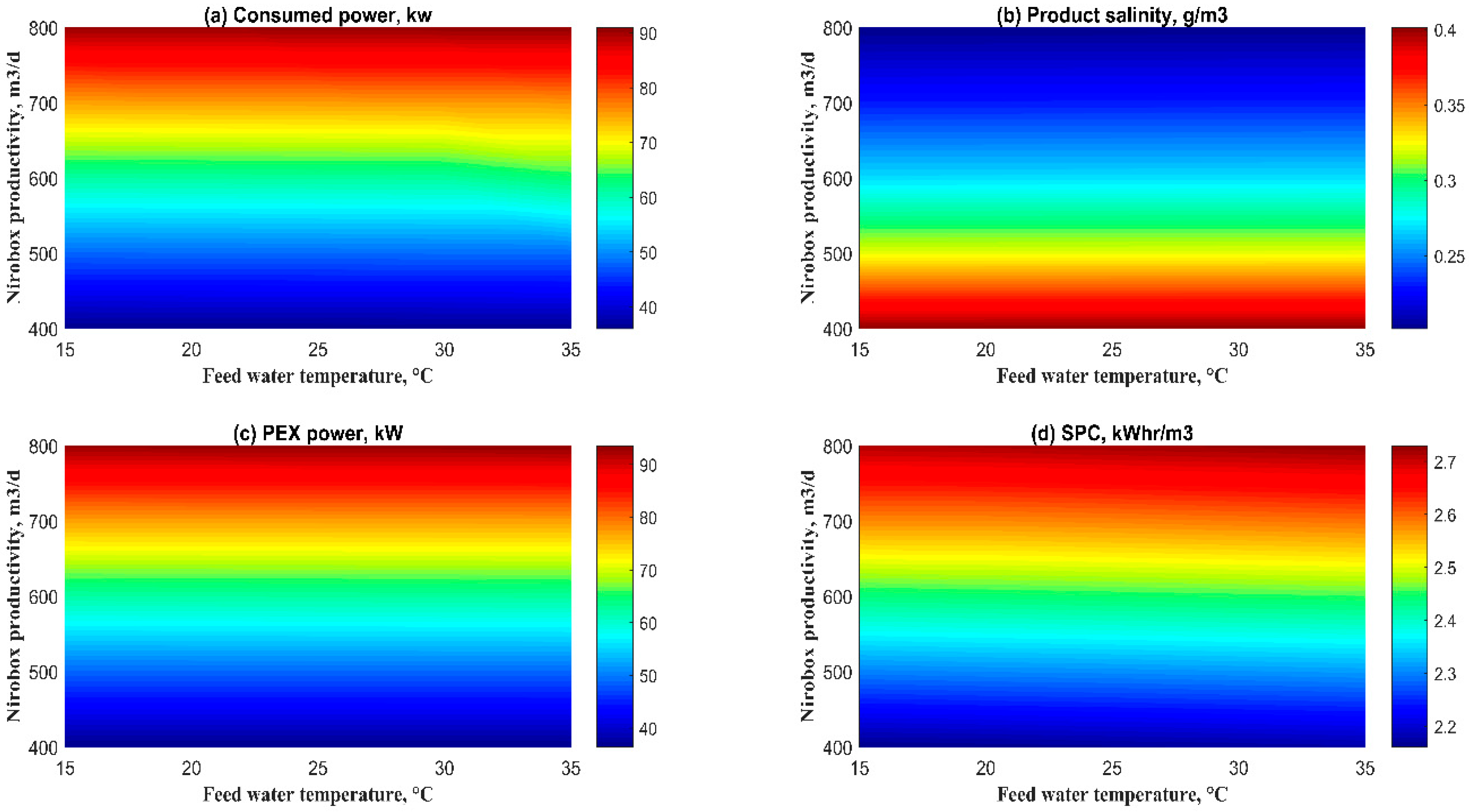

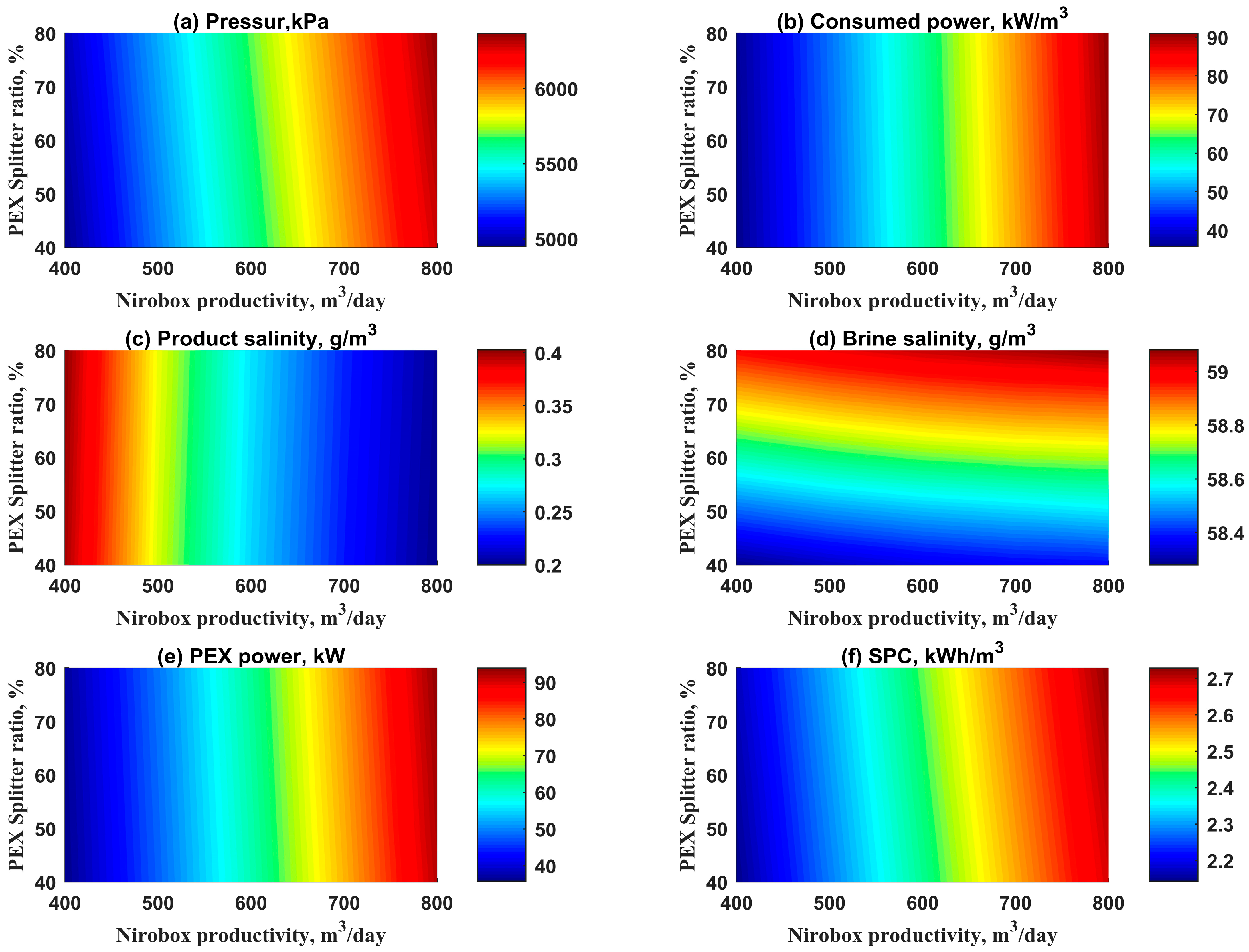

5. Results and Discussions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| A | Area, m2 |

| BF | Backing factor, % |

| CIP | Cleaning-In-Place |

| Cp | Specific heat capacity, kJ/kg °C @ constant pressure |

| FF | Fill factor, % |

| HP | High pressure, bar |

| HHP | High pressure pump |

| LF | Load factor, % |

| LP | Low pressure, bar |

| M | Mass flow rate, m3/h, kg/s |

| Max | Maximum |

| Min | Minimum |

| Nbr, N, n, | Number, # |

| P | Power, kW, or Pressure, bar |

| PEX | Pressure exchanger |

| pH | potential Hydrogen, # |

| RO | Reverse Osmosis |

| RR | Recovery ratio, % |

| SPC | Specific power consumption, kWh/m3 |

| SR | Salt rejection, % |

| T | Temperature, °C |

| TDS | Total Dissolved Solids, ppm |

| k | Permeability |

| X | Salinity ratio, g/kg (ppm) |

| Y | Extraction percentage, % |

| Subscripts | |

| a, amb | Ambient |

| av | Average |

| b | Brine |

| d | Distillate product, discharge |

| e | Element |

| f | Feed |

| h | High, Hour |

| i | In |

| o | Out |

| p | Product or pump |

| th | Thermal |

| total | Total |

| s | Salt |

| spl | Splitted feed |

| t | Time |

| w | Water |

| Greek symbol | |

| Δ | Difference |

| η | Efficiency, % |

| ρ | Density, kg/m3 |

| π | Osmotic pressure, kPa |

References

- Tianbao, S.; Lu, L.; Jianwei, B.; Xidong, X.; Yulian, Y.; Chunyou, P. Key points of design and equipment selection of reverse osmosis seawater desalination high-pressure system. Water Purif. Technol. 2019, 38, 131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Kalyan, I.; Nayak, A.K.; Khobragade, M.U. Addressing the global water crisis: A comprehensive review of nanobiohybrid applications for water purification. In Nanobiohybrids for Advanced Wastewater Treatment and Energy Recovery; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2023; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, W. Global Water Crisis: Too Little, Too Much, or Lack of a Plan; Christian Science Monitor: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Baseer, M.A.; Kumar, V.V.; Izonin, I.; Dronyuk, I.; Velmurugan, A.K.; Swapna, B. Novel hybrid optimization techniques to enhance reliability from reverse osmosis desalination process. Energies 2023, 16, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, C.; Franks, R.; Andes, K. Operational performance and optimization of RO wastewater treatment plants. Singap. Int. Water Week Singap. 2010. Available online: https://membranes.com/wp-content/uploads/Documents/Technical-Papers/Application/Waste/Operational-Performance-and-Optimization-of-RO-Wastewater-Treatment-Plants-1.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Panagopoulos, A.; Haralambous, K.-J. Environmental impacts of desalination and brine treatment-Challenges and mitigation measures. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 161, 111773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kress, N. Marine Impacts of Seawater Desalination: Science, Management, and Policy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Eke, J.; Yusuf, A.; Giwa, A.; Sodiq, A. The global status of desalination: An assessment of current desalination technologies, plants and capacity. Desalination 2020, 495, 114633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, M. Sustainable seawater reverse osmosis desalination as green desalination in the 21st century. J. Membr. Sci. Res. 2020, 6, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Aroussy; Saifaoui, D.; Lilane, A. Exergetic and thermo-economic analysis of different multi-effect configurations powered by solar power plants. Desalination Water Treat 2021, 235, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Karaghouli, A.; Kazmerski, L.L. Energy consumption and water production cost of conventional and renewable-energy-powered desalination processes. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 24, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.; Qadir, M.; van Vliet, M.T.; Smakhtin, V.; Kang, S. The state of desalination and brine production: A global outlook. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 1343–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilane, A.; Saifaoui, D.; Aroussy, Y.; Hariss, S.; Oulhazzan, M. Experimental study of a pilot membrane desalination system: The effects of transmembrane pressure. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 30, 970–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilane, A.; Saifaoui, D.; Aroussy, Y.; Chouiekh, M.; Eldean, M.S.; Mabrouk, A. Simulation and optimization of pilot reverse osmosis desalination plant powered by photovoltaic solar energy. Desalination Water Treat. 2022, 258, 16–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stover, R.L. Seawater reverse osmosis with isobaric energy recovery devices. Desalination 2007, 203, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettani, M.; Bandelier, P. Techno-economic assessment of solar energy coupling with large-scale desalination plant: The case of Morocco. Desalination 2020, 494, 114627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stover, R.L. Retrofits to improve desalination plants. Desalination Water Treat. 2010, 13, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adda, A.; Naceur, W.M.; Abbas, M. Modélisation et optimisation de la consommation d’énergie d’une station de dessalement par procédé d’osmose inverse en Algérie. J. Renew. Energ. 2016, 19, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essa, F.A.; Selim, F. Improving the operation of small reverse osmosis plant using Pelton turbine and supplying emergency electric loads. Energy Sources Part. Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2023, 45, 12040–12055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanezi, A.A.; Altaee, A.; Sharif, A.O. The effect of energy recovery device and feed flow rate on the energy efficiency of reverse osmosis process. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2020, 158, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zahrani, A.; Orfi, J.; Al-Suhaibani, Z.; Salim, B.; Al-Ansary, H. Thermodynamic analysis of a reverse osmosis desalination unit with energy recovery system. Procedia Eng. 2012, 33, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, F.; Nie, S.; Yin, F.; Lu, W.; Ji, H.; Ma, Z.; Kong, X. Numerical and experimental research on the integrated energy recovery and pressure boost device for seawater reverse osmosis desalination system. Desalination 2022, 523, 115408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voutchkov, N. Energy use for membrane seawater desalination–current status and trends. Desalination 2018, 431, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Kim, J.; Yang, D.R.; Hong, S. Towards a low-energy seawater reverse osmosis desalination plant: A review and theoretical analysis for future directions. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 595, 117607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fievrez, E.; Bonnélye, V. Impact environnemental du dessalement: Contraintes et avancées. Rev. THE 2009, 142, 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Schunke, A.J.; Herrera, G.A.H.; Padhye, L.; Berry, T.-A. Energy recovery in SWRO desalination: Current status and new possibilities. Front. Sustain. Cities 2020, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, S.; Wang, K.; Xiao, Y.; Ma, Q.; Song, D.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Y. Developmental impediment and prospective trends of desalination energy recovery device. Desalination 2024, 578, 117465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-García, A.; Nuez, I.; Khayet, M. Performance assessment and modeling of an SWRO pilot plant with an energy recovery device under variable operating conditions. Desalination 2023, 555, 116523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niasse, M.; Afouda, A.; Amani, A. Reducing West Africa’s Vulnerability to Climate Impacts on Water Resources, Wetlands, and Desertification: Elements for a Regional Strategy for Preparedness and Adaption; IUCN–the World Conservation Union: Gland, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Noureddine, G.; Eslamian, S.; Katlane, R. Status of water resources and Climate change in Maghreb regions (Mauritania, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya). Int. J. Water Sci. Environ. Technol. Sci. Press. Int. Ltd. 2021, 6, 67–94. [Google Scholar]

- Okafor, J.C.; Ononogbu, O.A.; Ojimba, A.C.; Ani, C.C. Trans-border Mobility and Security in the Sahel: Exploring the Dynamics of Forced Migration and Population Displacements in Burkina Faso and Mali. Society 2023, 60, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntaghry, K.; Thiam, A.; Habib, S.M.S.; Faye, K.; Faye, M. Evaluation of suitable sites for concentrated solar power desalination systems: Case study of Mauritania. Environ. Res. Commun. 2024, 6, 085020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacoub, E.; Tayfur, G. Spatial and temporal of variation of meteorological drought and precipitation trend analysis over whole Mauritania. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2020, 163, 103761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddah, H.A.; Alzhrani, A.S.; Almalki, A.M.; Bassyouni, M.; Abdel-Aziz, M.H.; Zoromba, M.; Shihon, M.A. Determination of the treatment efficiency of different commercial membrane modules for the treatment of groundwater. J. Mater. Env. Sci. 2017, 8, 2006–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mengesha, A.; Sahu, O. Sustainability of membrane separation technology on groundwater reverse osmosis process. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2022, 7, 100457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilane, A.; Saifaoui, D.; Ettami, S.; Chouiekh, M.; Aroussy, Y.; Eldean, M.A.S. Modeling and simulation of solar chimney/HWT power plant for the assistance of reverse osmosis desalination and electric power generation. Desalination Water Treat. 2023, 286, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, A.; Bennett, J.M.; Marchuk, A.; Marchuk, S.; Biggs, A.J.W.; Raine, S.R. Validating laboratory assessment of threshold electrolyte concentration for fields irrigated with marginal quality saline-sodic water. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 205, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaf, M.A. Thermo-economic comparisons of different types of solar desalination processes. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 2012, 134, 031001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilane, A.; Saifaoui, D.; Ettami, S.; Chouiekh, M.; Aroussy, Y. Simulation and optimization of a RO/EV pilot reverse osmosis desalination plant powered by PV solar energy: The application to brackish water at low concentration. Eur. Phys. J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 97, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilane, A.; Saifaoui, D.; Hariss, S.; Jenkal, H.; Chouiekh, M. Modeling and simulation of the performances of the reverse osmosis membrane. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 24, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.E.; Hashaikeh, R.; Diabat, A.; Hilal, N. Mathematical and optimization modelling in desalination: State-of-the-art and future direction. Desalination 2019, 469, 114092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaf, M.A. Design and Simulation of Solar Desalination Systems; Suez Canal University: Ismailia, Egypt, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, Y.; Irfan, M.; Gul, S. Modeling Approach to Estimate Energy Consumption of Reverse Osmosis and forward Osmosis Membrane Separation Processes for Seawater Desalination. Mater. Proc. 2024, 17, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Mg2+ | Ca2+ | Na+ | K+ | SO42− | HCO3− | Cl− | pH | T (°C) | Turbidity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TDS (mg/L) | 1403 | 441 | 11,640 | 428 | 2920 | 152.8 | 20,932 | 8.17 | 25.5 | <1 |

| Operating Specifications | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| LG Chem 440ES membrane | Surface | 41 m2 |

| Rejection ration | 99.8% | |

| Min. Salt Rejection | 99.6% | |

| Max. HP Applied | 82.7 bar | |

| Max. Chlorine concentration | <0.1 ppm | |

| Max. Temperature of operation | 45 °C | |

| pH Range, Continuous (Cleaning) | 2–11 (2–13) | |

| Max. Feedwater turbidity | 1.0 NTU | |

| Max. Feed flow | 17 m3/h | |

| Max. Pressure drop | (1.0 bar) | |

| PEX iSave 50 | Max. HP out—HP in | 5 bar |

| Max. HP out | 83 bar | |

| Min. HP out | 40 bar | |

| Max. LP in (MAWP) | 5 bar | |

| Min. HP in | 2 bar | |

| Min. pressure LP in | 2 bar | |

| Differential pressure (LP in, max—LP out, max) | 0.53 bar | |

| Speed | [525–650] rpm | |

| Flow at min. speed, HP out, in | 42 m3/h | |

| Flow at max. speed, HP out | 52 m3/h | |

| Max. allowable working flow, LP in | 57.2 m3/h | |

| Salinity at 40% RR | 2–3% | |

| Motor Efficiency at 60 bar | 93.7% | |

| Pressure vessel | Producer company | Belvessel |

| Model | BEL8-S-1000 | |

| Max. operating pressure | 69 bar | |

| Min. operating pressure | 1 bar | |

| Max. operating pressure | 49 °C | |

| Min. operating temperature | 5 °C | |

| MATLAB Results | Experimental Results | |

|---|---|---|

| Specified parameters | ||

| Tamb, °C | 25 | 25 |

| TSeawater, °C | 20 | 20 |

| Feed water salinity, kg/m3 | 38 | 38 |

| Nbr of pressure elements, - | 5 | 5 |

| Nbr of vessels, - | 10 | 10 |

| RO surface, m2 | 41 | 41 |

| Total surface, m2 | 2050 | 2050 |

| HPP efficiency, % | 80 | 80 |

| Recovery ratio, % | 34.25 | 34.25 |

| Feed splitter ratio, % | 68 | 67 |

| RO-PEX system performance data | ||

| SPC, kWh/m3 | 2.52 | 2.55 |

| Pressure, kPa | 5862 | 6060 |

| Feed flow rate, m3/h | 80 | 80 |

| Brine flow rate, m3/h | 52.60 | 52.60 |

| Brine salinity, kg/m3 | 58.85 | -- |

| Product salinity, kg/m3 | 0.2451 | 0.291 |

| Salt rejection, % | 99.37 | 98.44 |

| Product flow rate, m3/h | 27.4 | 27.4 |

| Feed to the booster pump, m3/h | 54.4 | 56.9 |

| Split flow rate by PEX unit, m3/h | 26.6 | 27.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ghadhy, A.; Lilane, A.; Faraji, H.; Ettami, S.; Boulezhar, A.; Saifaoui, D. Performance Analysis of Seawater Desalination Using Reverse Osmosis and Energy Recovery Devices in Nouadhibou. Liquids 2026, 6, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/liquids6010002

Ghadhy A, Lilane A, Faraji H, Ettami S, Boulezhar A, Saifaoui D. Performance Analysis of Seawater Desalination Using Reverse Osmosis and Energy Recovery Devices in Nouadhibou. Liquids. 2026; 6(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/liquids6010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhadhy, Ahmed, Amine Lilane, Hamza Faraji, Said Ettami, Abdelkader Boulezhar, and Dennoun Saifaoui. 2026. "Performance Analysis of Seawater Desalination Using Reverse Osmosis and Energy Recovery Devices in Nouadhibou" Liquids 6, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/liquids6010002

APA StyleGhadhy, A., Lilane, A., Faraji, H., Ettami, S., Boulezhar, A., & Saifaoui, D. (2026). Performance Analysis of Seawater Desalination Using Reverse Osmosis and Energy Recovery Devices in Nouadhibou. Liquids, 6(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/liquids6010002