1. Introduction

The widespread use of pipeline transport characterised the second half of the 20th century. During this period, pipeline transport was used to transport homogeneous liquids, gases, polymer solutions, solid bulk materials, containers, air mixtures and hydro mixtures [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Of all these pipeline transport types, the transport of aqueous suspensions containing solid particles smaller than 100 microns is considered the most complex and promising area. The peculiarities of the interactions among solid-phase particles in the suspension and with the liquid phase impose additional requirements on the calculation of hydraulic and technological parameters for this type of transport [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. The experience of domestic and foreign specialists indicates that such problems cannot be solved solely by methods of hydrodynamics of a heterogeneous medium. This scientific problem lies at the intersection of several sciences: hydrodynamics, rheology and physical chemistry [

2,

7,

9,

10]. Pipeline hydrotransport of structured suspensions (SS) has seen its most significant development in the technologies of manufacturing and transporting water–coal fuel (WCF) [

2,

3,

5,

6,

8,

9,

13,

14]. At the time when the idea of burning coal in the form of a structured water–coal suspension arose, well-developed methods of hydromechanics already existed for flows of polymer solutions of various concentrations in chemical technologies [

15,

16] or clay solutions in drilling and well cementing technologies [

17,

18,

19]. This made it possible to quickly create the scientific basis for calculating the hydraulic parameters of pipeline systems for supplying WCS and to implement them in industry [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. These methods are mainly based on accounting for the rheological characteristics of WCS, and the operating modes of hydrotransport systems did not provide for stops and restarts. Experience operating pipeline systems for supplying WCF has shown that most SS, unlike other types of hydraulic mixtures with solid particles larger than 100 microns, can remain stable for several days, with a uniform distribution of solid-phase particles throughout the volume. This means that flushing the system after shutdown and before start-up is not necessary. This raised new questions for researchers about WCF’s stability. That is why the further development of methods for calculating the parameters of pipeline transportation of WCF can be considered the application of the theory of stability of lyophobic colloids by Derjaguin–Landau–Verwey–Overbeek (DLVO); this made it possible to take into account the influence of gravitational and repulsive forces of an ionic–electrostatic and Van der Waals nature on flow regimes and hydrotranport parameters [

2,

7]. New prospects for applying the scientific basis for calculating pipeline transport of WCF emerged at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries, when the first technologies for pressure hydrotransport of mineral processing waste in the form of SS began to be developed and implemented [

4,

16]. Later, technologies for developing man-made deposits and deposits formed in artificial storage facilities began to be developed [

6,

20,

21]. To this, we should add the latest approaches to enrichment waste storage facilities, which provide for their reprocessing and disposal, already being designed on the basis that SS will be used [

1,

4,

8,

14].

Thus, SS pipeline transport technologies have good prospects for use in the 21st century. Still, their widespread and effective implementation requires modernisation of the scientific basis for calculating the main parameters and operating modes, which will take into account not only rheological and hydraulic characteristics but also ionic–electrostatic and Van der Waals forces.

The main difference between SS flow in a pipeline and Newtonian fluid flow is the presence of an undeformed flow core located along the flow axis. Traditionally, the ratio of the initial tangential stress to the tangential stress of hydraulic friction on the inner surface of the pipe is used to determine the radius of the undeformed flow core. However, some experimental studies of SS pressure flows in pipelines indicate that the radius of the undeformed flow core obtained in this way cannot be used at minimal values or near unity [

15,

22]. The reasons for this phenomenon are unknown. The methods limit these intervals, assuming that, in the first case, turbulent flow has already been achieved and, in the second, laminar flow has already begun. There is a hypothesis that these effects are manifestations of ion-electrostatic and Van der Waals forces.

Recent experimental studies confirm that rheological behaviour of coal–water slurries (CWS) is highly sensitive to particle size distribution, solids loading, and dispersant chemistry, with modern dispersants (including sustainable lignin based molecules) able to reduce apparent viscosity and modify yield stress and thixotropy in ways that directly affect pipeline pressure drop and plug core formation [

23]. Comparative rheometry and pressure pipe tests further demonstrate that apparent yield stress and shear thinning indices measured in laboratory rheometers must be interpreted with caution when applied to long distance hydrotransport, because wall slip, particle migration and structural rebuilding under low shear can alter the effective core radius in service conditions [

24,

25].

At the particle scale, DLVO remains a useful baseline for estimating the balance of electrostatic repulsion and van der Waals attraction, but recent reviews emphasise important refinements: ion-specific (Hofmeister) effects, surface heterogeneity, and medium-dependent Hamaker constants can substantially shift interaction potentials and aggregation thresholds for mineral and coal particles [

26,

27,

28]. Experimental and theoretical work on nanoparticle and mineral systems shows that the total interaction energy is not always well represented by classical DLVO alone; non-DLVO contributions and ion-specific adsorption can change both the magnitude and sign of the interaction energy at relevant separations [

29,

30,

31].

Bridging micro- and macro-scales, recent studies have quantified how interparticle interaction energies translate into macroscopic stability and restructuring under shear, linking zeta potential and dispersant adsorption to measurable changes in rheology and sedimentation propensity [

23,

32,

33]. These works support the approach taken here of treating the lyophobicity parameter as a measurable function that modifies the radius of the undeformed core through additional energetic terms, rather than as an abstract correction factor [

23].

From a hydrotransport engineering perspective, contemporary reviews and field studies of paste and slurry pipelines highlight that pipeline performance (deposition velocity, restart behaviour, wear) depends on the interplay between yield stress, thixotropy and particle interactions, and that predictive models must therefore couple rheological constitutive laws with interaction energy informed stability criteria to be reliable for design and operation [

34]. This multi-scale coupling is particularly important for coal-based slurries where mineral inclusions and surface chemistry produce variable Hamaker constants and ion specific behaviour that affect both short-term shear stability and long-term storage stability [

27,

28].

2. Methods

According to the results obtained within the framework of the DLVO theory and adapted to the conditions of the pressure flow of the WCF, the destruction of the suspension structure, accompanied by an uneven distribution of solid phase particles throughout the suspension volume, occurs when the following condition is met [

2,

11,

16,

20,

21]:

where

is the total energy of interaction between two spherical particles in a liquid;

is the external energy of the flow directed at destroying the bond between the two particles.

Regarding the formula for determining the total interaction energy of two spherical particles in a liquid, most researchers propose the classical dependence of the DLVO theory [

2,

11,

16,

20,

21]:

where

—reverse Debye radius, in most cases 10

8 m

−1;

—parameter of energy interaction of solid phase particles SS;

—absolute dielectric permeability of liquid phase SS, 7.26 × 10

−10 F/m;

—radius of solid phase particles SS, m;

—potential of a diffuse particle of a double electric layer on the surface of solid phase particles SS, V;

—distance between solid phase particles SS, m;

—constant equal to 3.14;

—dimensionless distance between particles of the solid phase of SS, m;

—Hamaker constant, J.

While calculating the external energy of a flow aimed at destroying the connection between two particles, different researchers propose different approaches [

2,

3,

7,

10,

11,

12,

14,

16,

21].

There is a well-known hypothesis that this energy is proportional to the difference in the velocities of the flows impinging on two adjacent particles [

2,

3]:

where

is the Coriolis coefficient;

is the density of the liquid phase;

is the difference in the velocities of the flows impinging on two adjacent particles in the coagulation structure, m/s;

S is the cross-sectional area of the flow impinging on a single particle, m

2;

is the duration of the flow, s.

The authors of dependence (3) do not explain why the energy of the flow is considered rather than the energy of the particles obtained from the flow. There is also no explanation of how to calculate the values of S and t. In general, the duration of the flow is characteristic of turbulent flows, with corresponding velocity pulsations along and across the flow. However, the structure breaks down before turbulence develops. The presence of the Coriolis coefficient in formula (3), which reflects the uneven distribution of the kinetic energy of the flow across the cross-sectional area, also requires additional justification.

Other authors believe that the external energy of the flow directed at destroying the connection between two particles is the kinetic energy of these particles, and propose the following dependence [

5,

7]:

where

is the difference in the velocities of the particles under consideration relative to each other, m/s;

is the density of the solid phase.

Dependence (4) is very close to the difference in kinetic energies of interacting particles, provided that their sizes and densities are the same. However, in this case, instead of the square of the difference in the velocities of the particles under consideration relative to each other, it is necessary to use the difference in the squares of the velocities of these particles.

Within the hypothesis on which formula (4) is based, different results can be obtained for estimating the relative radius that defines the flow region where SS will not be destroyed, if different patterns of velocity distribution along the pipe radius are assumed [

10,

11,

12,

14,

16,

21]. There are known cases of using the logarithmic law [

20,

21], which does not correspond to the conditions in the layer between the inner surface of the pipeline and the undeformed flow core. Many specialists who have studied the peculiarities of non-Newtonian fluid flow in a pipeline note that if we consider the destruction of the suspension structure during SS flow in a pipeline, the velocity distribution in the layer near the pipeline surface will correspond to the following dependence [

10,

11,

16]

where

U—local flow velocity SS;

—pipe radius, m;

—current radius value, m;

—relative current radius;

—tangential stress of hydraulic friction on the inner surface of the pipe, Pa;

—dynamic viscosity coefficient of the liquid phase of the fluid, kg/m/s;

—relative radius of the undeformed flow core;

—initial tangential stress of the fluid flow, Pa;

—pressure difference at the beginning and end of the pipeline, Pa;

—pipeline length, m.

The flow velocity (5) represents the near-wall shear layer before the onset of fully developed turbulence. This profile is therefore assumed valid for laminar and pre-transitional regimes, and for flows in which near-wall shear dominates the deformation of the suspension structure. In practice, this corresponds to pipe Reynolds numbers below the conventional transition threshold.

Using dependence (5), the difference in the velocities of two particles of the solid phase SS, after neglecting the square of the relative distance between the particles of the solid phase SS, can be calculated using the following formula [

16]:

which made it possible to obtain a condition under which the structure of the suspension is destroyed when the SS flows in the pipeline [

16]:

where

is the maximum value of the relative radius at which the suspension structure is still preserved during the flow of SS in the pipeline;

is the relative distance between the particles of the solid phase of SS. We adopt the uniform convention that the suspension structure is destroyed when the polynomial expression

P(

s) satisfies

P(

s) ≤ 0; this convention is used for (7), (10) and (11).

Note that the double sign in the second formula (7) appeared after taking the square root, i.e., it reflects a mathematical pattern, not a physical one. In addition, note that under the first root on the right side of the second formula (7) is the relative value of the total interaction energy of two spherical particles in a liquid, the first formula (2). This value is zero at equilibrium points but becomes positive or negative in other cases. At the same time, if we consider the second formula (7) at equilibrium points, its second term is zero. It coincides with the dependence for determining the relative radius at which the suspension structure is still preserved during SS flow in the pipeline, solely based on rheological and hydraulic characteristics, the second formula in (5).

In our opinion, if we consider that the external energy of the flow directed at destroying the connection between two particles is the kinetic energy of these particles, then it must be equal to the difference in the kinetic energies of the adjacent particles. That is, with the exact sizes and densities of these particles, this difference in kinetic energies will be proportional to the difference in the squares of the velocities at which each of the compatible particles will move under the action of the flow:

where

is the velocity of the particle with the smaller current radius, m/s;

is the velocity of the particle with the larger current radius, m/s.

The results of fundamental research on the flow of hydro-mixtures through pipelines, carried out by domestic authors [

1,

4,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

16,

20,

21], indicate that the difference between the velocity of the liquid phase and the hydraulic size of this particle determines the velocity of a solid particle in a hydro-mixture flow. Based on this experimental fact and using the first formula from (5), after the appropriate transformations, we write the following dependencies to calculate the velocities of each of the adjacent particles:

where

—hydraulic particle size of the solid phase, m/s.

Neglecting in the second formula (9) the quadratic term with the relative distance between the particles of the solid phase SS yields

The difference between the squares of the velocities in dependence (8) can be easily written as follows

where

—dimensionless hydraulic particle size of the solid phase, m/s.

Considering the first formula of the last two (8), the first formula of (2) and inequality (1), and taking into account that

After the appropriate transformations, we obtain a condition under which the structure of the suspension is destroyed when the SS flows in the pipeline, in the form of the following inequality:

where

is the lyophobicity parameter, which takes into account the influence of gravitational and repulsive forces of an ionic–electrostatic and Van der Waals nature. The lyophobicity parameter

B is dimensionless here.

The results of the analysis of the orders of magnitude on the left side (10) indicate that the second term of this polynomial can be neglected in comparison with the others. The dimensionless hydraulic particle size of the solid phase, in the case of WCF and most mineral processing wastes, is several orders of magnitude smaller than the square of the dimensionless thickness of the deformed part of the flow. The dimensionless hydraulic size

b is small because

w <<

U near the wall layer used in (5); empirically,

b =

O (10

−3–10

−2). Based on this, inequality (10) can be rewritten as follows:

If we consider condition (7) at equilibrium points, when 0

B, we obtain a restriction on the relative current radius

which coincides with the dependence for determining the relative radius at which the suspension structure is still preserved during SS flow in the pipeline, based exclusively on rheological and hydraulic characteristics, the second formula in (5).

Note that in inequality (11), the lyophobicity parameter contains the relative value of the total interaction energy of two spherical particles in a liquid, the first of the formulas (2), but not under the square root, as is the case in formula (7). That is, if we consider (11) away from equilibrium points, the value of the lyophobicity parameter becomes either positive or negative, and the form of the inequality (11) changes. However, the sign of the lyophobicity parameter does not affect the sign of the discriminant of the corresponding cubic equation, which must be solved to determine the intervals of inequality (11). The sign of this discriminant depends on the ratio of the lyophobicity parameter and the relative radius of the undeformed flow core. This discriminant will be positive if the inequality

and the cubic Equation (11) has one real root, which is determined by the formula

With a positive discriminant, regardless of the sign of the lyophobicity parameter, we obtain the following formula for calculating the maximum value of the relative radius at which the suspension structure is still preserved during SS flow in the pipeline:

where

is the real root of Equation (11), determined by formula (12).

The effect of the lyophobicity parameter sign is a restriction imposed by

on the value of the relative current radius. Thus, in the case of a positive lyophobicity parameter,

, the relative current radius is limited from above:

and when negative,

, from below:

Condition (14) is physically impossible, since it presupposes the existence of a destruction boundary in the middle of the flow region where there is no deformation.

With a negative discriminant, the following inequality holds:

Regardless of the sign of the lyophobicity parameter, there are three valid roots of Equation (11):

and the intervals of existence of the solution of inequality (11) will be

Here s is the current relative radius (normalised by pipe radius R); a is the undeformed core relative radius. The roots s′ and s″ denote secondary relative radii that delimit intervals where the structure is destroyed; s* denotes the maximum admissible relative radius at which the structure is still preserved (physically meaningful root with a ≤ s* ≤ 1).

The influence of the sign of the lyophobicity parameter lies in the values of the second interval limits. Thus, in the case of a positive lyophobicity parameter,

, the values

and

are calculated as the sums of the relative radius of the undeformed flow core and the roots of Equation (11):

and in the case of a negative parameter,

, as differences:

The first constraint in (16), as well as (14), is physically impossible, i.e., with a negative discriminant in (11), only the second constraint in (16) needs to be considered. Formulas (17) and (18) show that in the case of a positive lyophobicity parameter, , the maximum value of the relative radius at which the suspension structure is still preserved during SS flow in the pipeline will exceed the relative radius of the undeformed flow core, which is determined by the rheological characteristics of SS. Conversely, for a negative lyophobicity parameter, the maximum relative radius at which the suspension structure is still preserved during SS flow in the pipeline will be less than the relative radius of the undeformed flow core, which is determined by the rheological characteristics of SS.

3. Results and Discussion

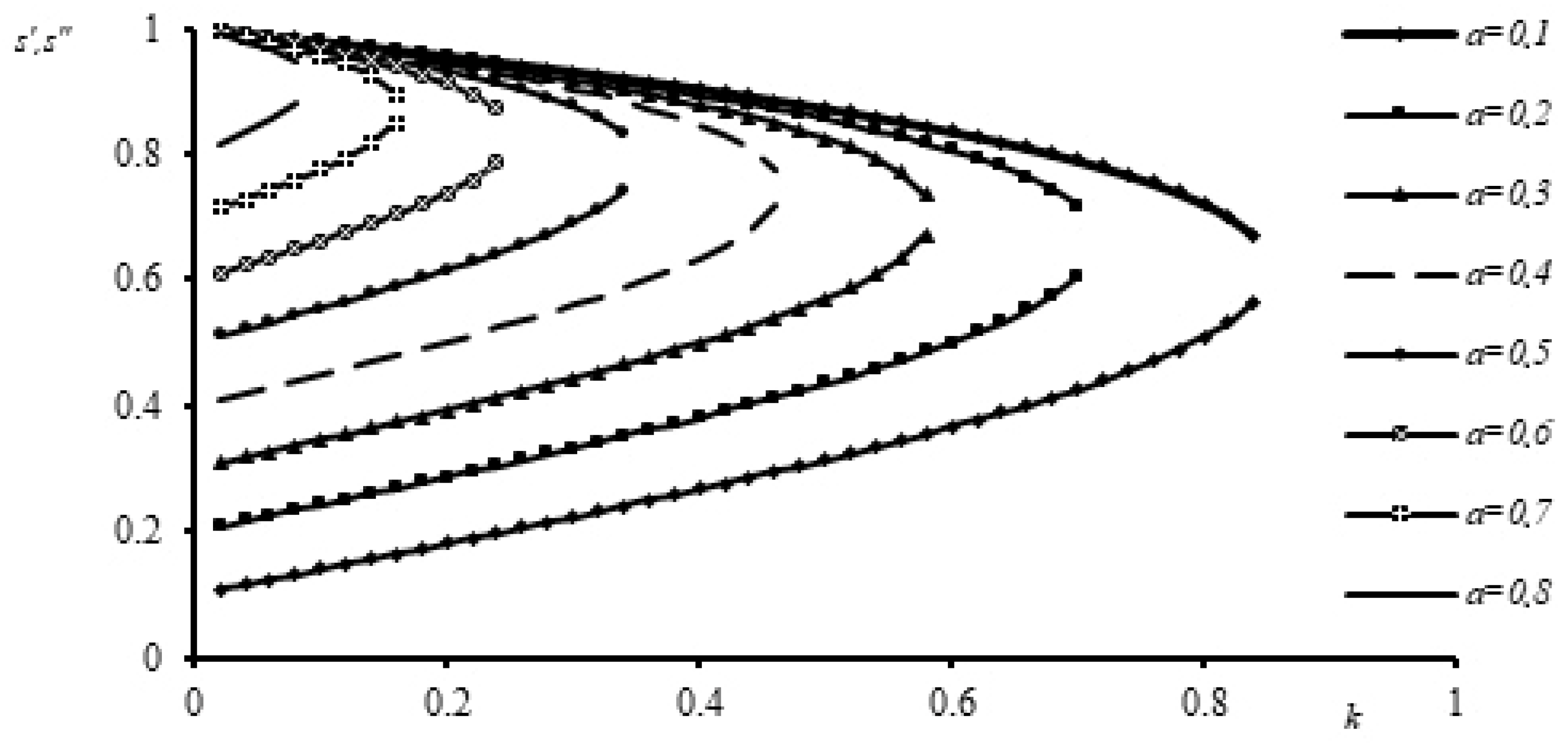

Analysis of formulas (11)–(18) indicates that the value of the lyophobicity parameter can be determined as a proportional function of the relative radius of the undeformed flow core

which allows, in the case of a positive discriminant, to determine the solution (12) in the following form

where

is the lyophobicity function (

Figure 1);

is the proportionality coefficient,

. The proportionality coefficient

k is not arbitrary, and also is dimensionless.

k increases with stronger electrostatic repulsion, lower van der Waals attraction, larger pipe radius and lower wall shear. Practically,

k can be estimated from measurable quantities: ζ-potential (electrophoretic mobility), ionic strength, (material pairing tables), and hydraulic calculation.

Calculations using the first formula (20) (

Figure 2) show that the values of the real root of Equation (11), determined by formula (12), may exceed the corresponding value of the relative radius of the undeformed flow core, which makes the values negative

(

Figure 3).

It is impossible to determine analytically the permissible values of the proportionality coefficient and the relative radius of the undeformed flow core that satisfy the condition

, given the nonlinear nature of the dependence (20). The results of numerical processing of the second formula from (20) show that the dependence of the lyophobicity function on the proportionality coefficient, with an accuracy acceptable for engineering calculations

, can be approximated by a step function:

Considering formulas (21), (20) and (13) together with the requirement of a positive value

, we obtained the following restrictions:

where

is the permissible value of the proportionality coefficient;

is the allowable value of the relative radius of the undeformed flow core.

By analogy with the case of a positive discriminant, in the case of a negative discriminant, the value of the lyophobicity parameter can be determined using (19), but with a different interval of existence:

which allows calculating the roots of Equation (11) (

Figure 4) and the corresponding limits at which the suspension structure is destroyed during SS flow in the pipeline (

Figure 5), since it becomes possible to calculate the cosine of the characteristic angle:

Figure 5 shows that the conditions of physical reality correspond to the second interval (16) (

Figure 6), the width of which is calculated using the following formula (

Figure 7):

where ∆ is the width of the interval relative to the current radius, where the suspension structure is destroyed during SS flow in the pipeline.

Note that when calculating using formulas (16)–(22), the value of the proportionality coefficient

is determined by the following formula:

Estimation pathway of k: measure ζ-potential (e.g., electrophoretic mobility) → compute from ionic strength → obtain x = 1/; select A for coal–water pairing; compute from hydraulic design; select R, a; evaluate F from flow energy definition; insert into (23) to compute k.

Comparison to Reported Anomalies at Small and Near-Unity Core Radii

The introduction noted that methods based solely on rheology fail for minimal and near-unity relative core radii [

15,

22]. In our framework,

Near-unity a→1: (1 − a)2 diminishes, and the free term a2B dominates. For B > 0 with positive discriminant, the unique root yields s* > a, implying a destruction boundary intruding into the undeformed region—physically ruled out and consistent with the empirical ‘invalid near unity’ observations. The model thus flags non-admissible solutions rather than mis-predicting feasible radii.

Very small a→0: (1 − a)2 is large, and the linear term enforces s* ≈ a unless B < 0 (dominant attraction), which reduces s* < a and narrows the stable zone, reproducing premature structure loss reported experimentally. Parameter sweeps over measured ζ-potential and ionic strength ranges show that the transition between admissible and inadmissible solutions aligns with the observed bounds. These results demonstrate how including DLVO interactions in the cubic inequality explains the anomalous regimes without ad hoc exclusions.

Taking into account various restrictions on the proportionality coefficient that exist for different values of the discriminant of Equation (11), relation (23) allows to limit the total interaction energy of two adjacent spherical particles in a liquid.

where

F is the external energy parameter of the flow.