Development of a Test Bed to Investigate Wetting Behaviours of High-Temperature Heavy Liquid Metals for Advanced Nuclear Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

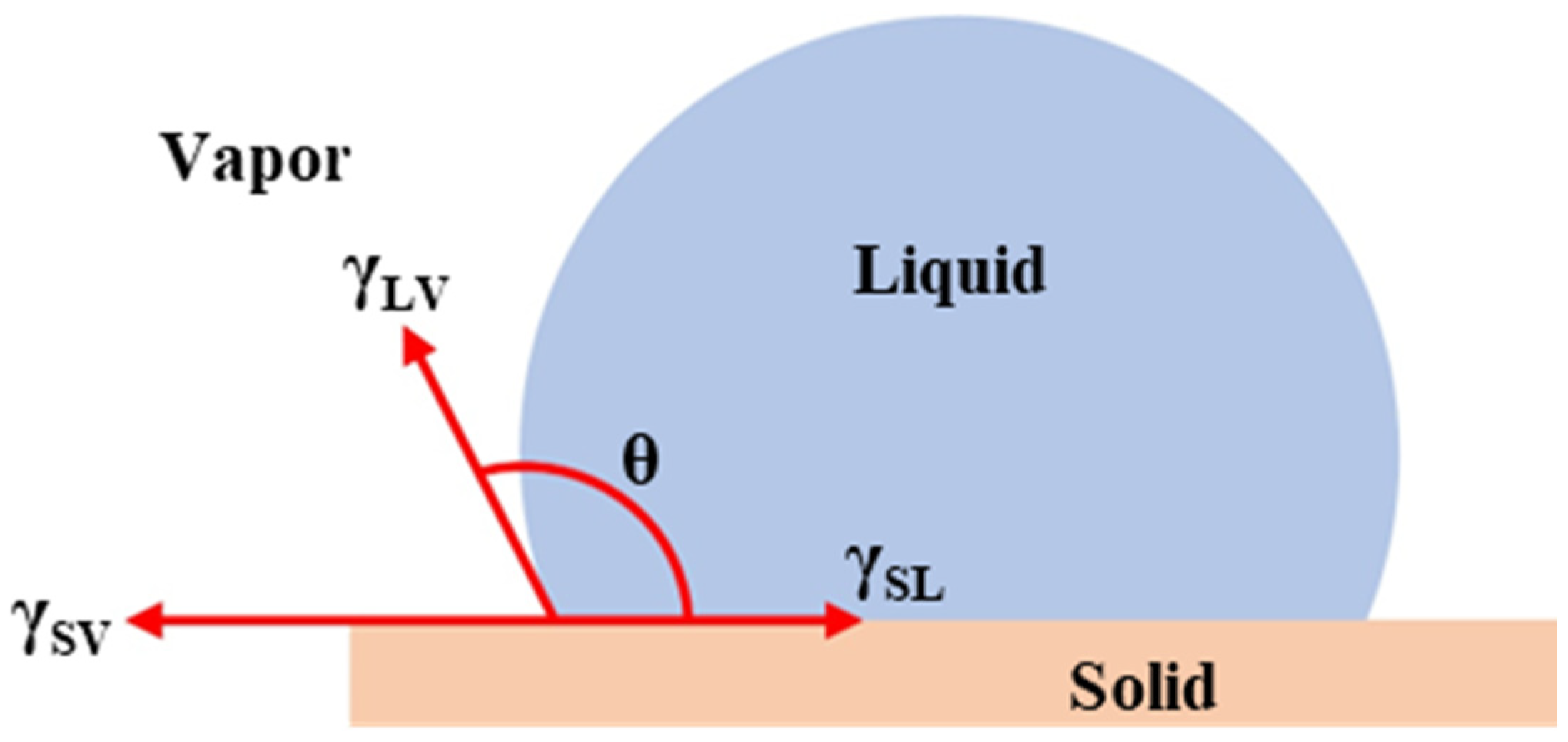

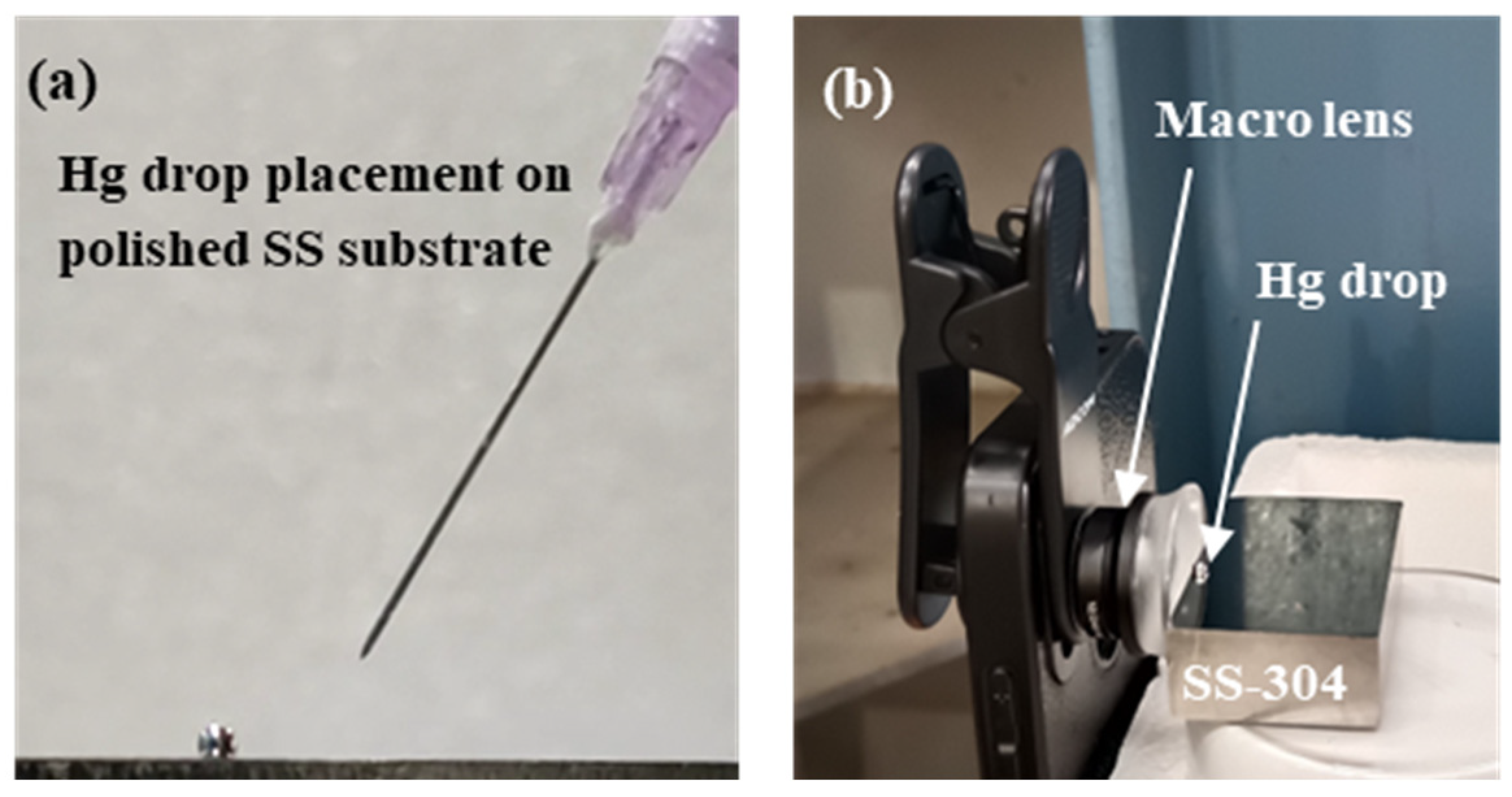

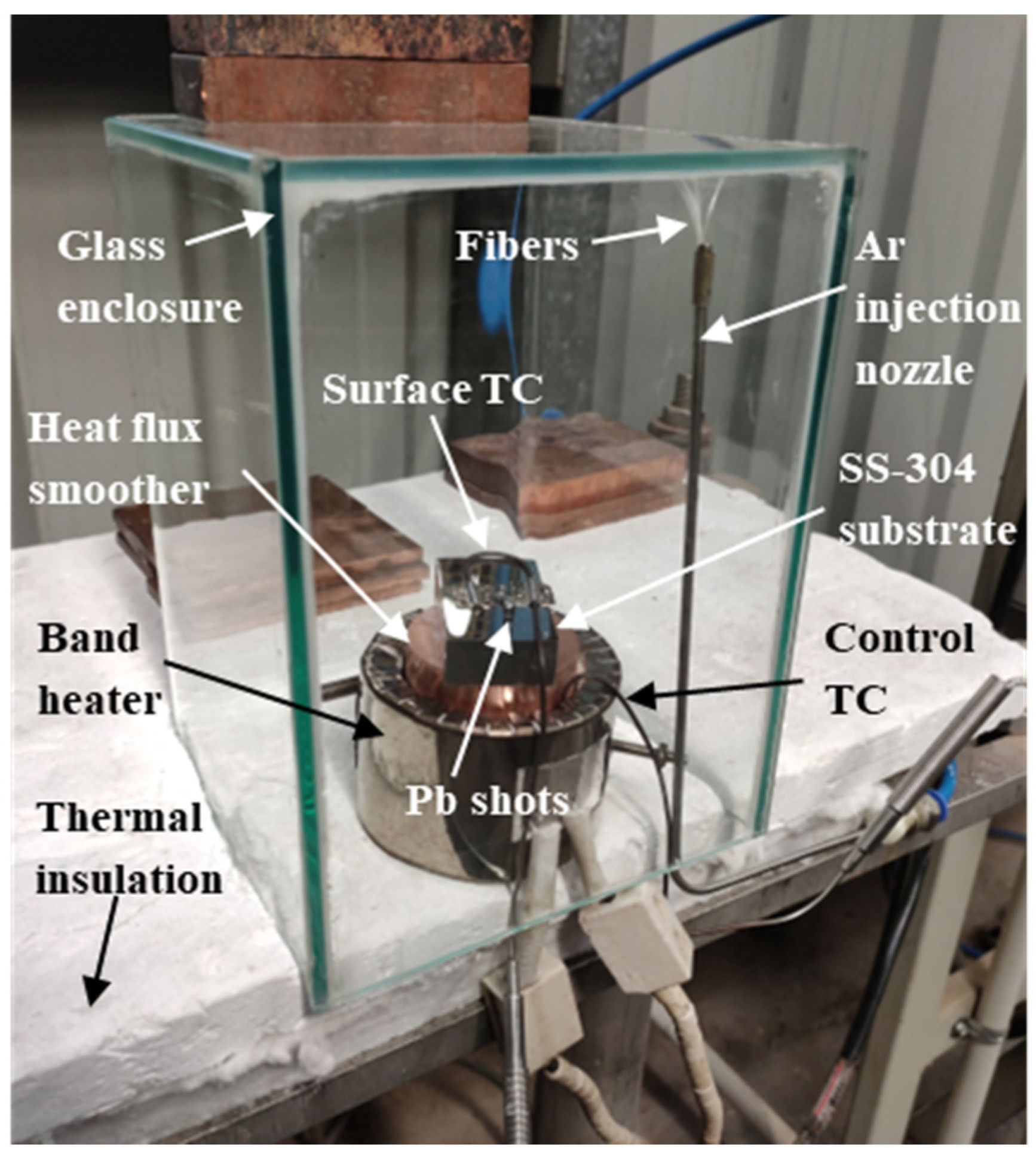

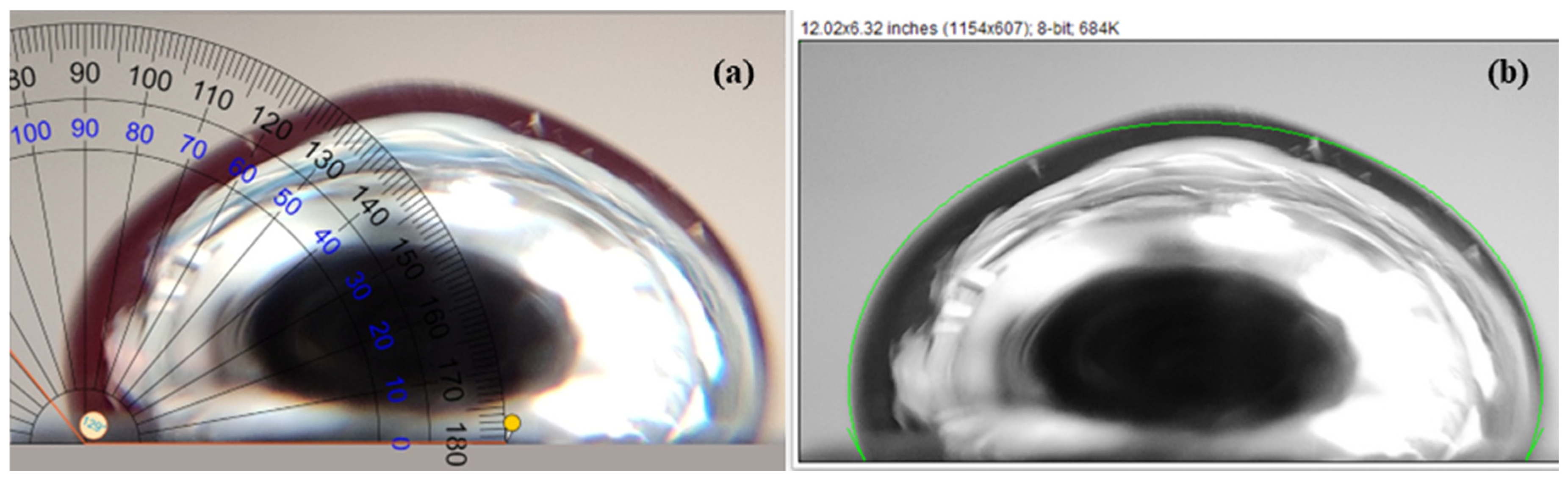

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Room-Temperature Measurements

3.2. High-Temperature Measurements for Molten Pb

3.3. Sources of Uncertainties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nuclear Energy Agency. Handbook on Lead-Bismuth Eutectic Alloy and Lead Properties, Materials Compatibility, Thermal-Hydraulics and Technologies; No. 7268; NEA: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks, J.R. Lead, Bismuth, Tin and Their Alloys as Nuclear Coolants. Nucl. Eng. Des. 1971, 15, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, P.; Del Nevo, A.; Moro, F.; Noce, S.; Mozzillo, R.; Imbriani, V.; Giannetti, F.; Edemetti, F.; Froio, A.; Savoldi, L.; et al. The DEMO Water-Cooled Lead–Lithium Breeding Blanket: Design Status at the End of the Pre-Conceptual Design Phase. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. A Review of Steel Corrosion by Liquid Lead and Lead–Bismuth. Corros. Sci. 2009, 51, 1207–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yang, C.; You, Y.; Yin, H. A Review of Corrosion Behavior of Structural Steel in Liquid Lead–Bismuth Eutectic. Crystals 2023, 13, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraswat, A.; Sasmal, C.; Prajapati, A.; Bhattacharyay, R.; Chaudhuri, P.; Gedupudi, S. Experimental Investigations on Electrical-Insulation Performance of Al2O3 Coatings for High Temperature PbLi Liquid Metal Applications. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2022, 167, 108856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, R.; Ningshen, S. Corrosion Behaviour of P-91 Steel and Type 316 LN Stainless Steel with and Without a Ceramic Coating in the Lead with Oxygen at 550 °C. J. Nucl. Mater. 2023, 574, 154181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraswat, A.; Fraile, A.; Gedupudi, S.; Bhattacharyay, R.; Chaudhuri, P. A Comprehensive Review of Experimental and Numerical Studies on Liquid Metal-Gas Two-Phase Flows and Associated Measurement Challenges. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2025, 213, 111104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, J.; Knapp, J.; Burrows, R.; Montague, R.; Arndt, J.; Walters, S. Achieving Wetting in Molten Lead for Ultrasonic Applications. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2024, 56, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolentsev, S.; Li, F.-C.; Morley, N.; Ueki, Y.; Abdou, M.; Sketchley, T. Construction and Initial Operation of MHD PbLi Facility at UCLA. Fusion Eng. Des. 2013, 88, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueki, Y.; Hirabayashi, M.; Kunugi, T.; Nagai, K.; Saito, J.; Ara, K.; Morley, N.B. Velocity Profile Measurement of Lead-Lithium Flows by High-Temperature Ultrasonic Doppler Velocimetry. Fusion Sci. Technol. 2011, 60, 506–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzel, T. Instrumentation. In Handbook on Lead-Bismuth Eutectic Alloy and Lead Properties, Materials Compatibility, Thermal-Hydraulics and Technologies; No. 7268; Nuclear Energy Agency NEA: Paris, France, 2015; Chapter 11; pp. 731–839. [Google Scholar]

- Zinkle, S.J.; Busby, J.T. Structural Materials for Fission & Fusion Energy. Mater. Today 2009, 12, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odette, G.R.; Zinkle, S.J. Structural Alloys for Nuclear Energy Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Narh, K.A.; Dwivedi, V.P.; Grow, J.M.; Stana, A.; Shih, W.-Y. The Effect of Liquid Gallium on the Strengths of Stainless Steel and Thermoplastics. J. Mater. Sci. 1998, 33, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawel, S.J. Summary of Mercury Compatibility Issues for the Spallation Neutron Source Target Containment and Ancillary Equipment; ORNL/TM-2002/280; Oak Ridge National Laboratory: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Stalder, A.F.; Melchior, T.; Müller, M.; Sage, D.; Blu, T.; Unser, M. Low-Bond Axisymmetric Drop Shape Analysis for Surface Tension and Contact Angle Measurements of Sessile Drops. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2010, 364, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Urrutia, A.; de Arroiabe, P.F.; Ramirez, M.; Martinez-Agirre, M.; Bou-Ali, M.M. Contact Angle Measurement for LiBr Aqueous Solutions on Different Surface Materials Used in Absorption Systems. Int. J. Refrig. 2018, 95, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiak, K.J.; Wilson, M.C.T.; Mathia, T.G.; Carval, P. Wettability Versus Roughness of Engineering Surfaces. Wear 2011, 271, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somlyai-Sipos, L.; Baumli, P. Wettability of Metals by Water. Metals 2022, 12, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.C. Surface Properties of Mercury. Chem. Rev. 1972, 72, 575–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, A.H.; Klemm, R.B.; Schwartz, A.M.; Grubb, L.S.; Petrash, D.A. Contact Angles of Mercury on Various Surfaces and the Effect of Temperature. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1967, 12, 607–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rallo, M.; Heidel, B.; Brechtel, K.; Maroto-Valer, M.M. Effect of SCR Operation Variables on Mercury Speciation. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 198–199, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

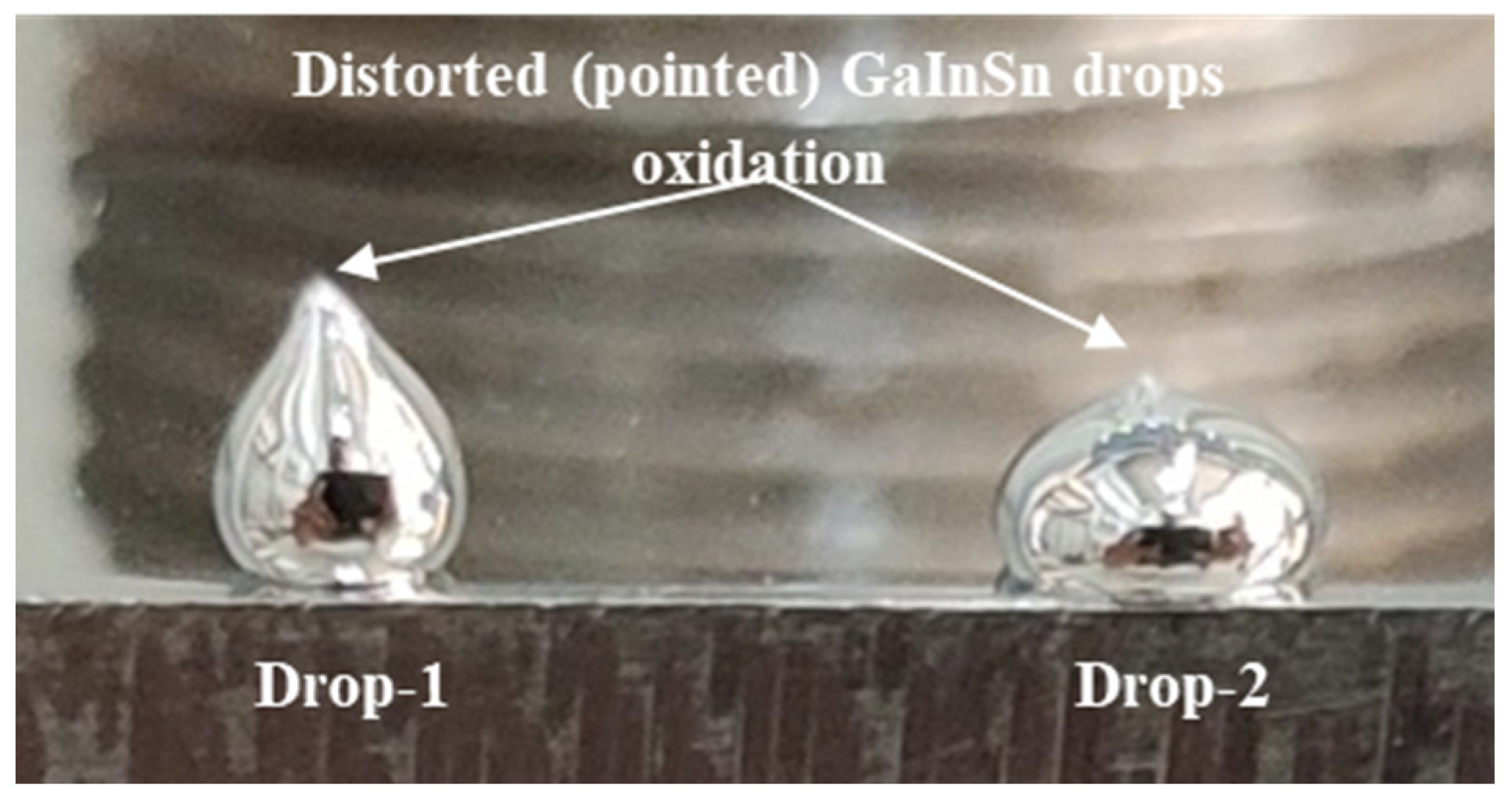

- Du, J.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Min, Q. How an Oxide Layer Influences the Impact Dynamics of Galinstan Droplets on a Superhydrophobic Surface. Langmuir 2022, 38, 5645–5655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, E.A. On the Wetting States of Low Melting Point Metal Galinstan and Wetting Characteristics of 3-Dimensional Nanostructured Fractal Surfaces. Master’s Thesis, Mechanical and Materials Engineering Department, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Sen, P.; Kim, C.-J. Characterization of Nontoxic Liquid-Metal Alloy Galinstan for Applications in Microdevices. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 2012, 21, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshipura, I.D.; Persson, K.A.; Truong, V.K.; Oh, J.-H.; Kong, M.; Vong, M.H.; Ni, C.; Alsafatwi, M.; Parekh, D.P.; Zhao, H.; et al. Are Contact Angle Measurements Useful for Oxide-Coated Liquid Metals? Langmuir 2021, 37, 10914–10923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickey, M.D. Emerging Applications of Liquid Metals Featuring Surface Oxides. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 18369–18379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

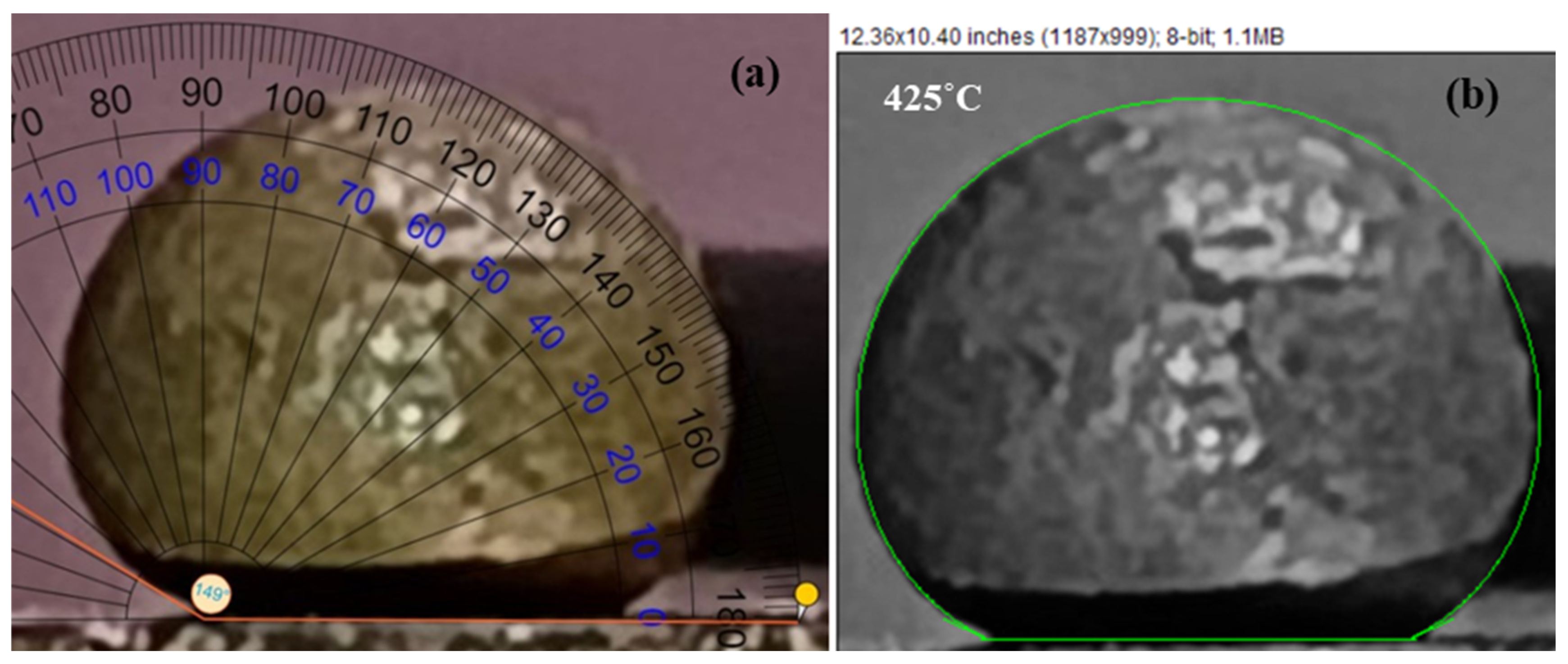

- Eustathopoulos, N.; Sobczak, N.; Passerone, A.; Nogi, K. Measurement of Contact Angle and Work of Adhesion at High Temperature. J. Mater. Sci. 2005, 40, 2271–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuranno, D.; Gnecco, F.; Ricci, E.; Novakovic, R. Surface Tension and Wetting Behaviour of Molten Bi–Pb Alloys. Intermetallics 2003, 11, 1313–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protsenko, P.; Terlain, A.; Jeymond, M.; Eustathopoulos, N. Wetting of Fe–7.5%Cr Steel by Molten Pb and Pb–17Li. J. Nucl. Mater. 2002, 307–311 Pt 2, 1396–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courouau, J.L. Chemistry Control and Monitoring Systems. In Handbook on Lead-Bismuth Eutectic Alloy and Lead Properties, Materials Compatibility, Thermal-Hydraulics and Technologies; No. 7268; Nuclear Energy Agency NEA: Paris, France, 2015; Chapter 4; pp. 185–238. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.L.; Kuhn, A.T.; Amann, M.A.; Hausinger, M.B.; Konarik, M.M.; Nesselrode, E.I. Computerised Measurement of Contact Angles. Galvanotechnik 2010, 101, 2502–2512. [Google Scholar]

- Handschuh-Wang, S.; Gan, T.; Wang, T.; Stadler, F.J.; Zhou, X. Surface Tension of the Oxide Skin of Gallium-Based Liquid Metals. Langmuir 2021, 37, 9017–9025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shone, A.; Koyn, Z.; Kamiyama, B.; Perez, E.; Barrus, L.; Bartlett, N.; Allain, J.P.; Andruczyk, D. HIDRA-MAT Liquid Metal Droplet Injector for Liquid Metal Applications in HIDRA. Fusion Eng. Des. 2022, 180, 113193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, C.L.; Marchhart, T.; Kawashimo, K.; Nieto-Perez, M.; Parsons, M.S.; Schamis, H.; Allain, J.P. A Liquid Metal Dropper for Experiments on the Wettability of Liquid Metals on Plasma Facing Components. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2023, 94, 103506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pair | θDirect imaging | θLBADSA | % Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| H2O/SS | 59.00° ± 1.22° | 61.09° ± 2.05° | 3.54 |

| Hg/SS | 149.67° ± 3.27° | 136.10° ± 4.41° | −9.07 |

| Ga/SS | 129.33° ± 3.39° | 119.72° ± 0.80° | −7.43 |

| GaInSn/SS | 115.83° ± 1.83° | 114.79° ± 1.40° | −0.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saraswat, A.; Bhattacharyay, R.; Chaudhuri, P.; Gedupudi, S. Development of a Test Bed to Investigate Wetting Behaviours of High-Temperature Heavy Liquid Metals for Advanced Nuclear Applications. Liquids 2025, 5, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/liquids5040033

Saraswat A, Bhattacharyay R, Chaudhuri P, Gedupudi S. Development of a Test Bed to Investigate Wetting Behaviours of High-Temperature Heavy Liquid Metals for Advanced Nuclear Applications. Liquids. 2025; 5(4):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/liquids5040033

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaraswat, Abhishek, Rajendraprasad Bhattacharyay, Paritosh Chaudhuri, and Sateesh Gedupudi. 2025. "Development of a Test Bed to Investigate Wetting Behaviours of High-Temperature Heavy Liquid Metals for Advanced Nuclear Applications" Liquids 5, no. 4: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/liquids5040033

APA StyleSaraswat, A., Bhattacharyay, R., Chaudhuri, P., & Gedupudi, S. (2025). Development of a Test Bed to Investigate Wetting Behaviours of High-Temperature Heavy Liquid Metals for Advanced Nuclear Applications. Liquids, 5(4), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/liquids5040033