Microbiome Indoles Dock at the TYR61–GLU67 Hotspot of Giardia lamblia FBPA: Evidence from Docking, Rescoring, and Contact Mapping

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Computational Environment and Code Availability

2.2. Target Structure (FBPA)

Receptor Preparation

2.3. Ligand Panel and Preparation

2.4. Docking Box Definition

2.5. Docking Protocol

- ▪

- Exhaustiveness: 16;

- ▪

- Number of poses: 20;

- ▪

- Energy range: 3 kcal·mol−1;

- ▪

- Replicates: 3 random seeds (− seed 1, 2, 3);

- ▪

- Output: best binding free energy (ΔG) and all docking poses.

2.6. Vinardo Rescoring and Internal Validation

2.7. Structural/Contact Analysis

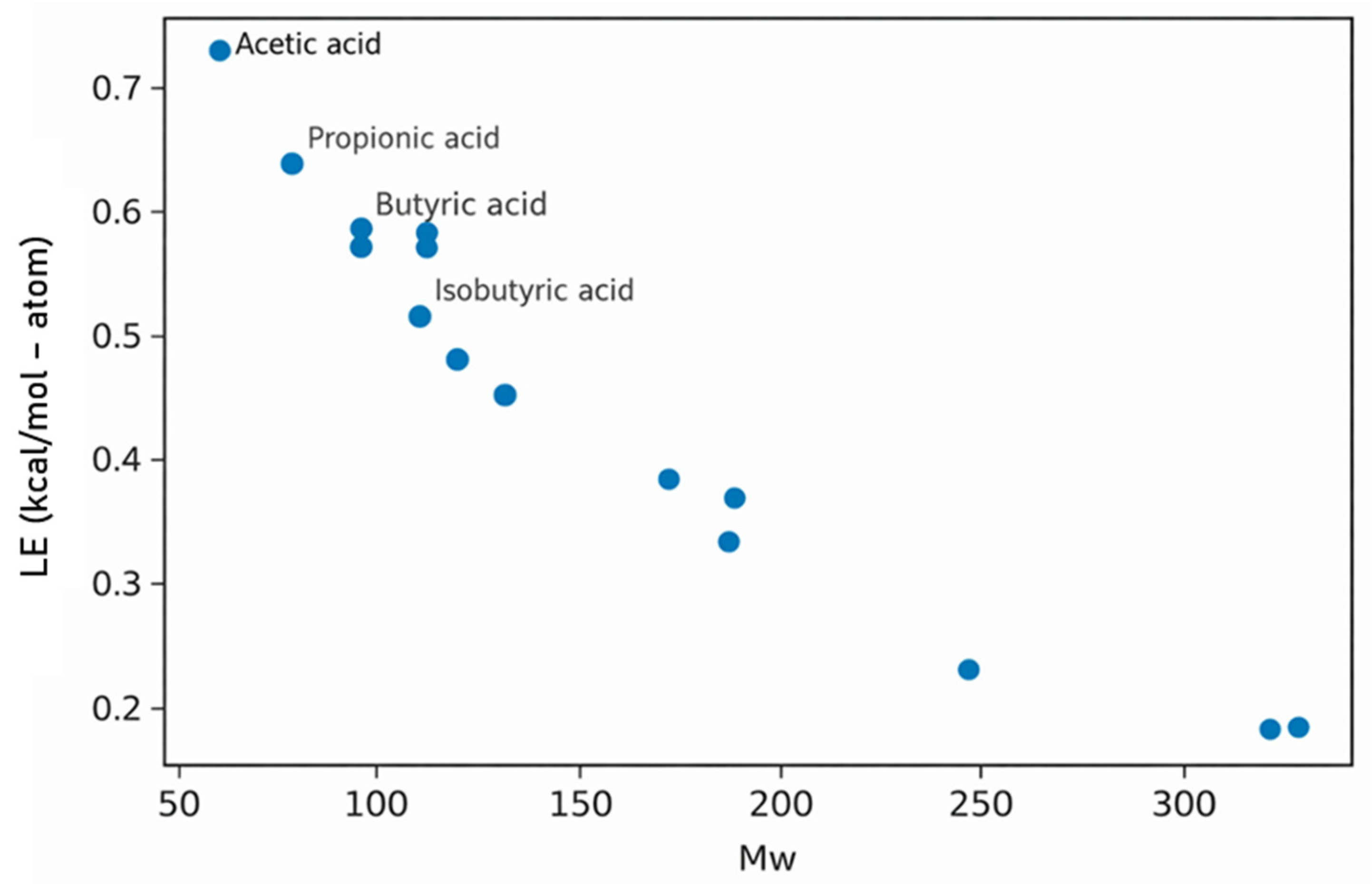

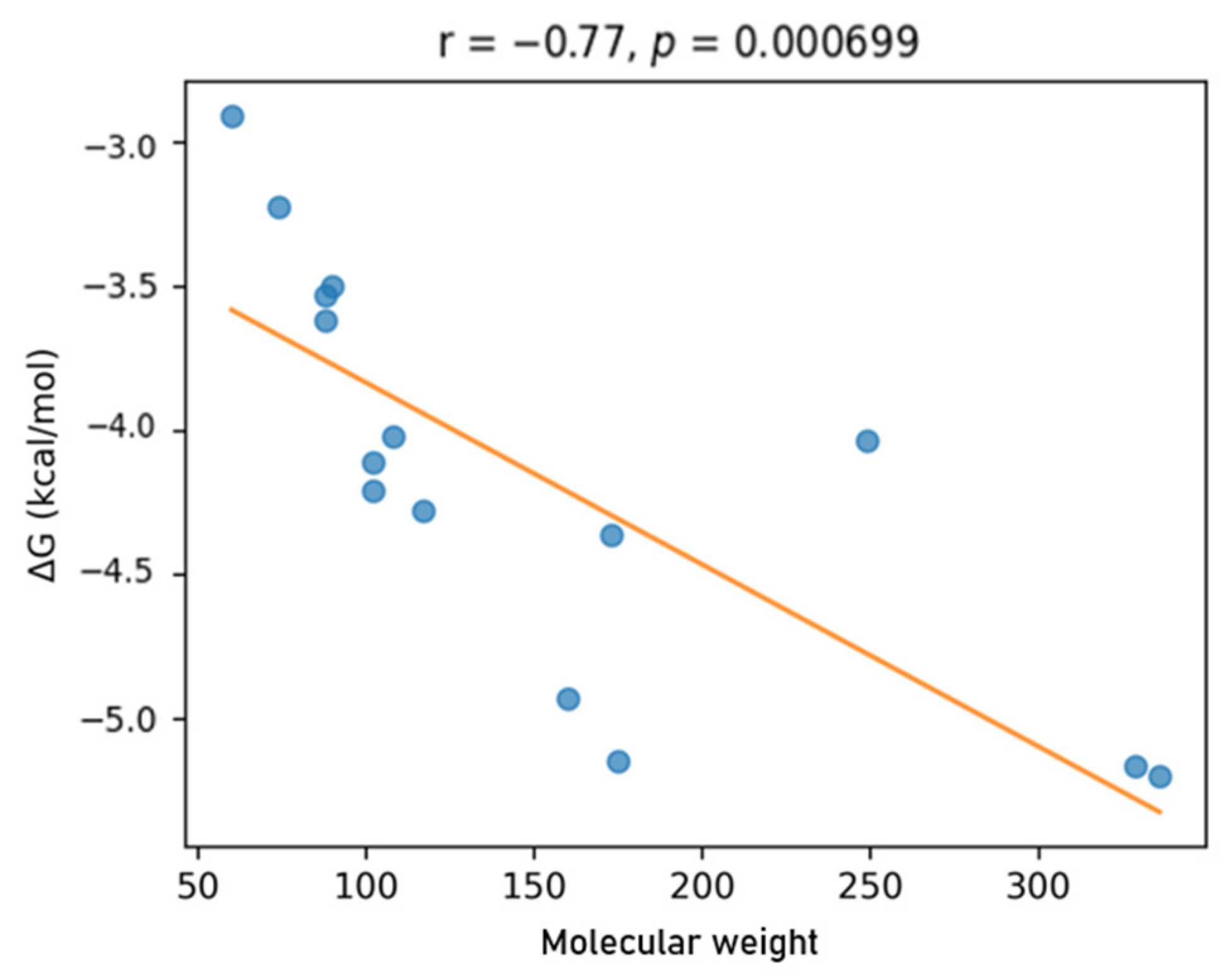

2.8. Physicochemical and Quality Metrics

Statistical Analysis

2.9. Reproducibility Checklist

2.10. Ethics Statement

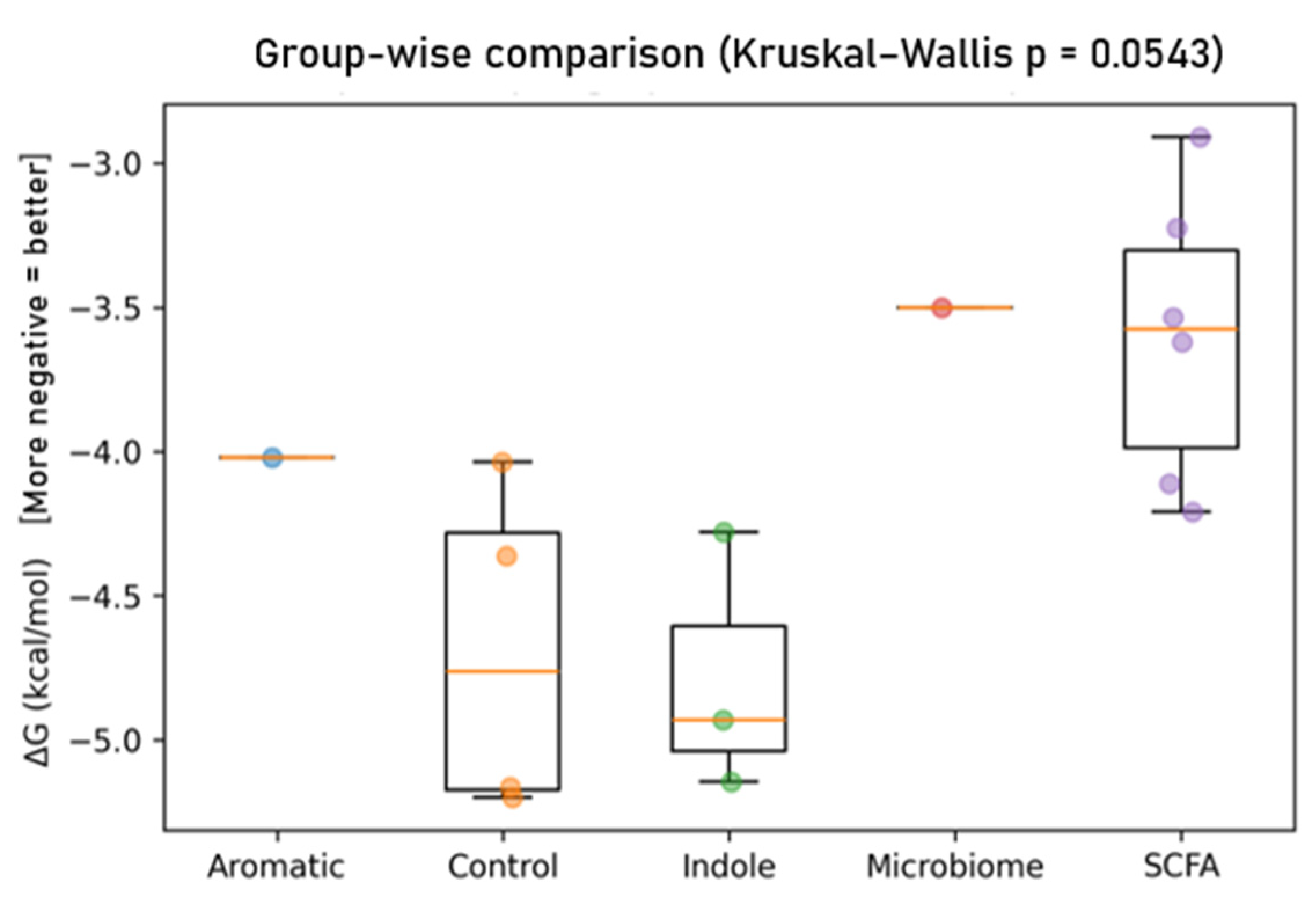

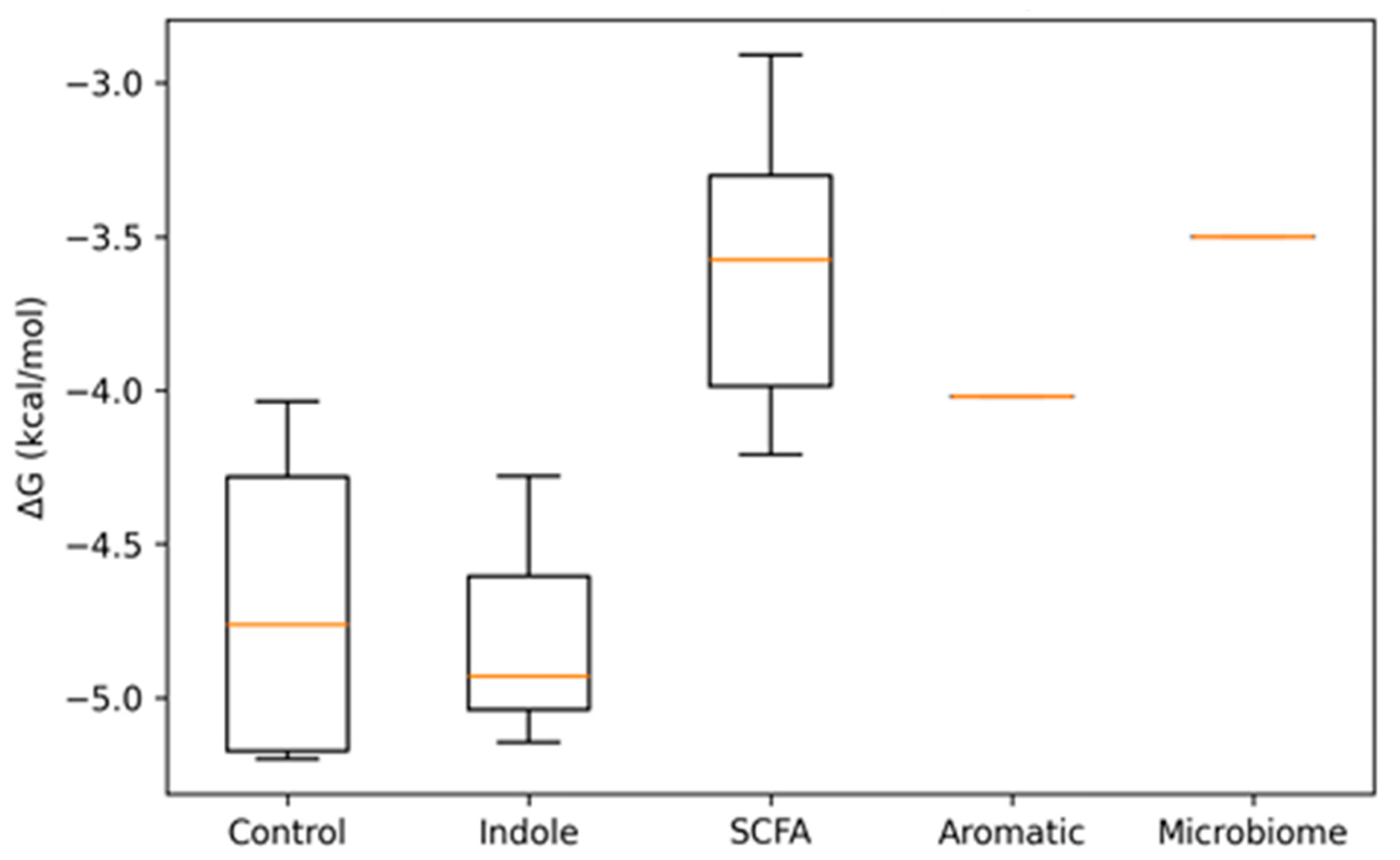

3. Results

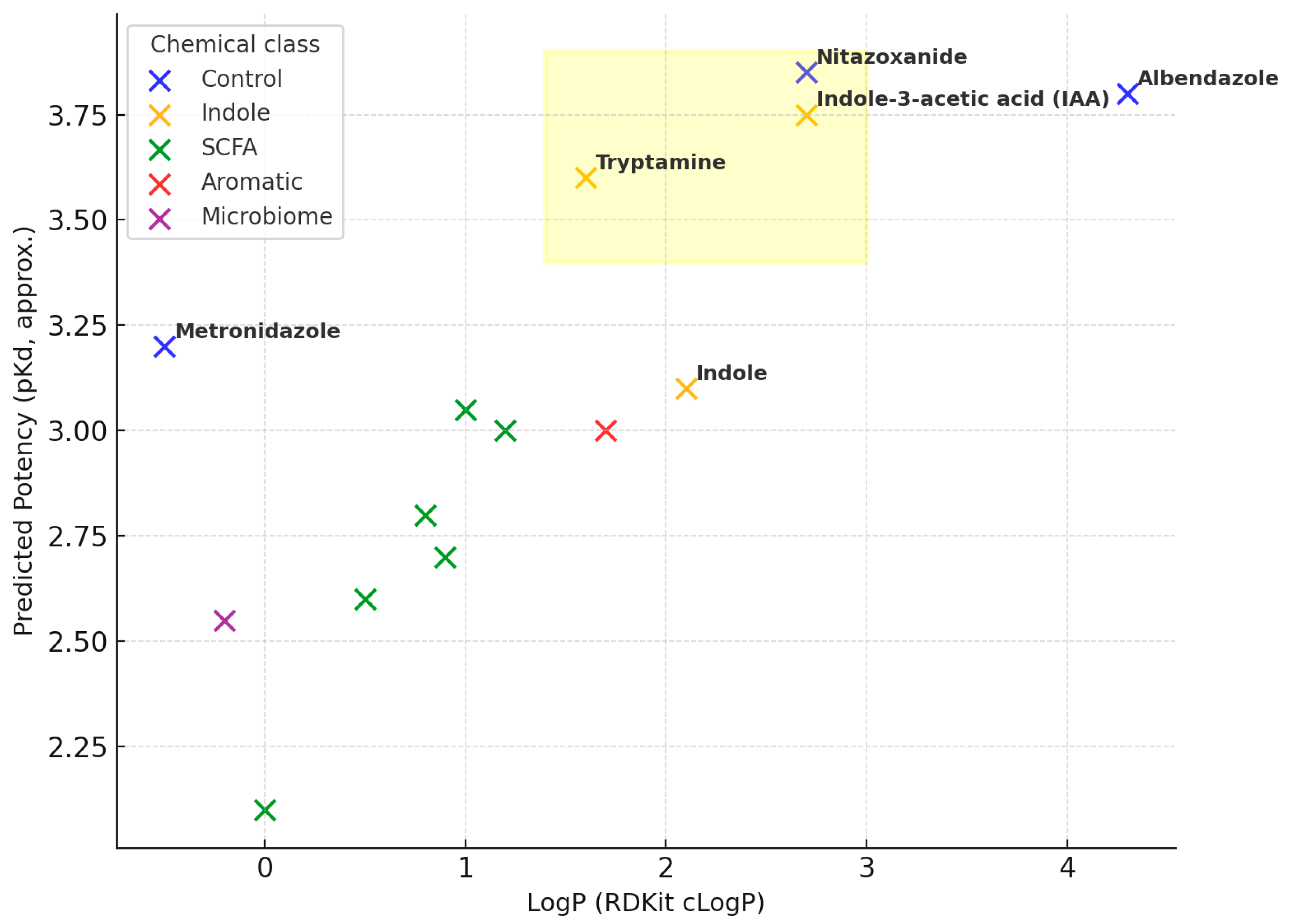

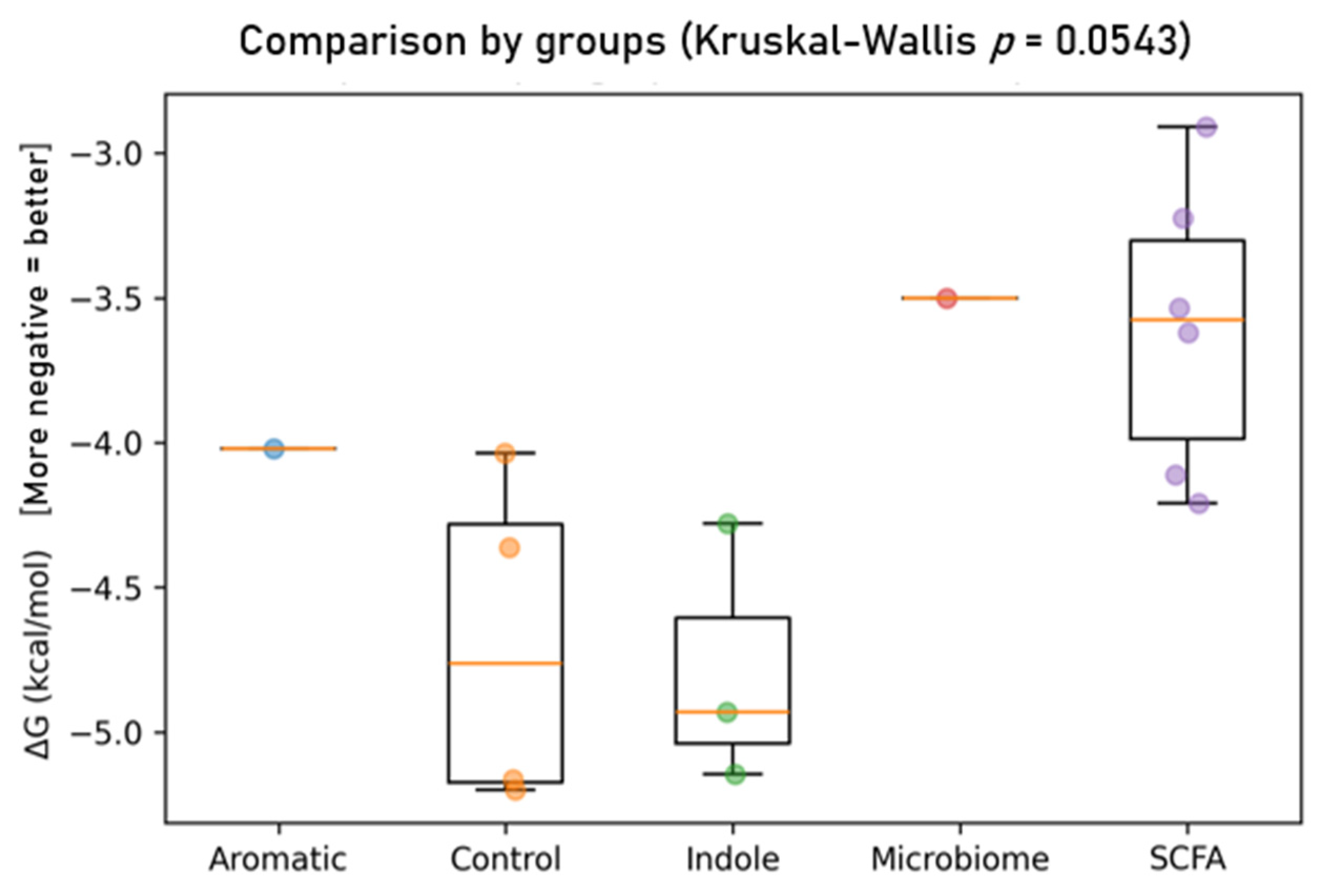

- (i)

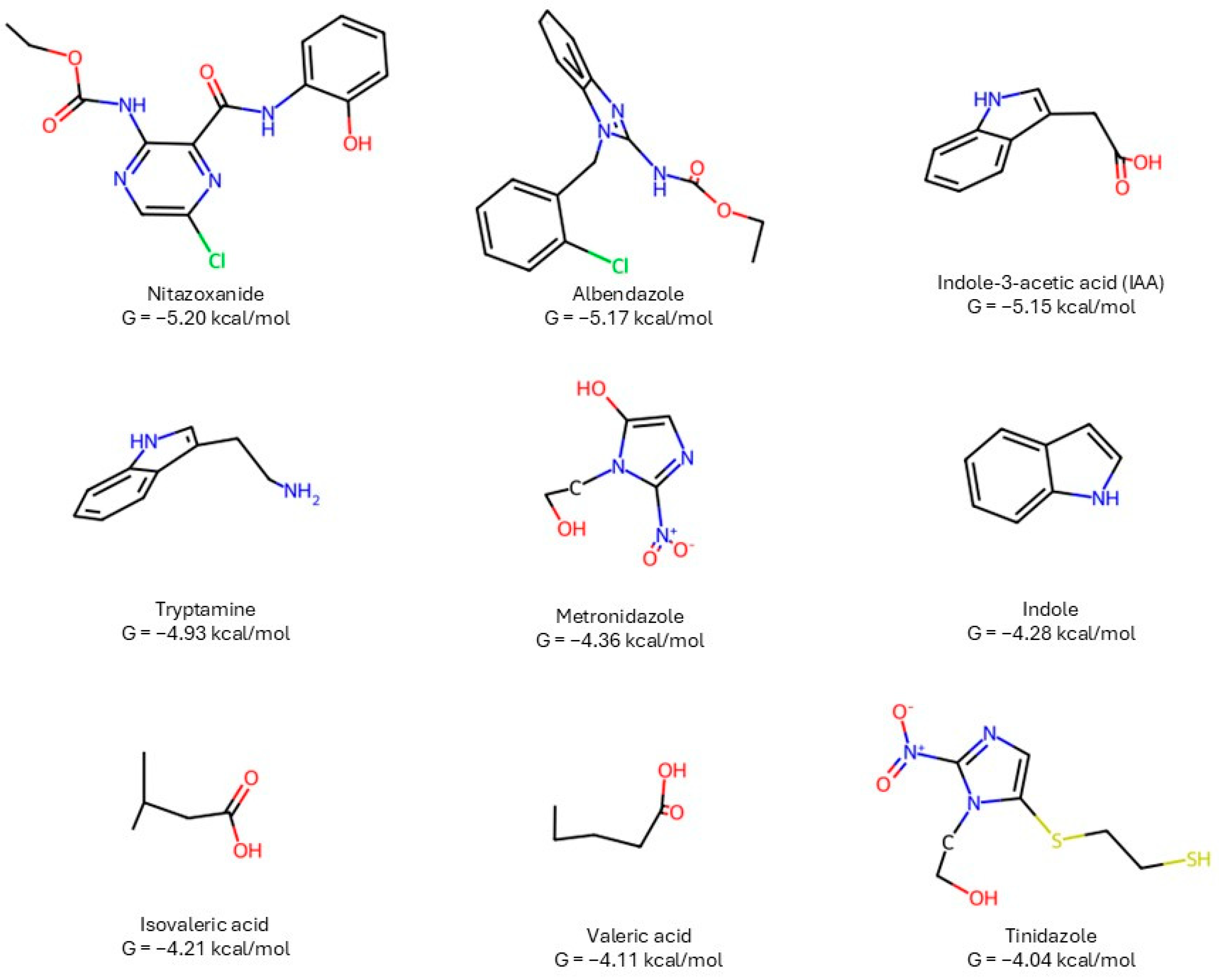

- Indoles—indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) (pKd ≈ 3.8, LogP ≈ 2.7) and tryptamine (≈3.6, 1.6)—show high potency at lower LogP;

- (ii)

- Controls—nitazoxanide (≈3.85, 2.7) achieves strong potency with moderate LogP, while albendazole (≈3.8, 4.3) is potent but lipophilicity-driven. Metronidazole sits at low LogP (~−0.5) with mid potency (~3.2). SCFAs cluster at lower potency (pKd ≈ 2.1–3.1) and modest LogP (≈0.5–1.2).

- ▪

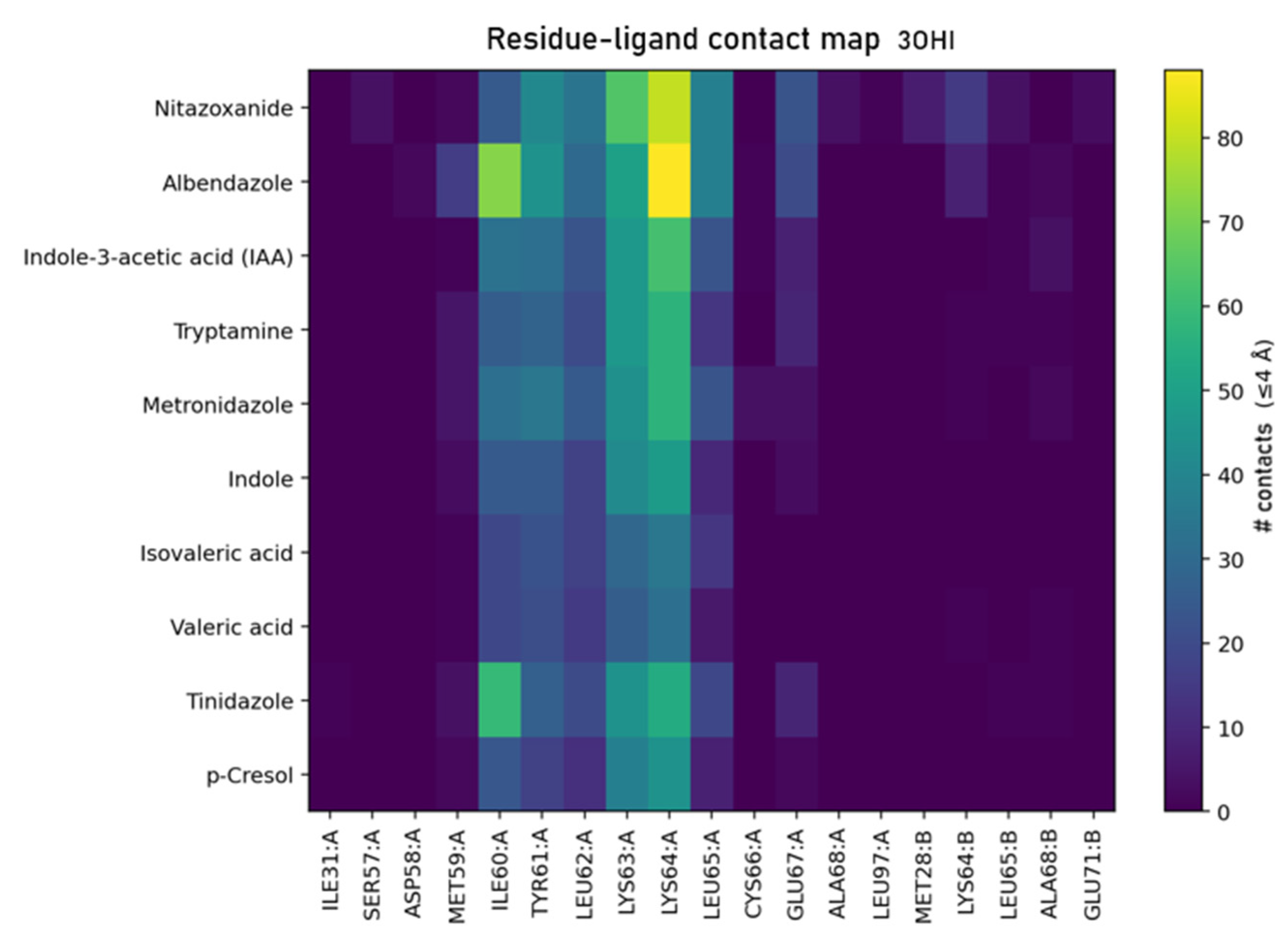

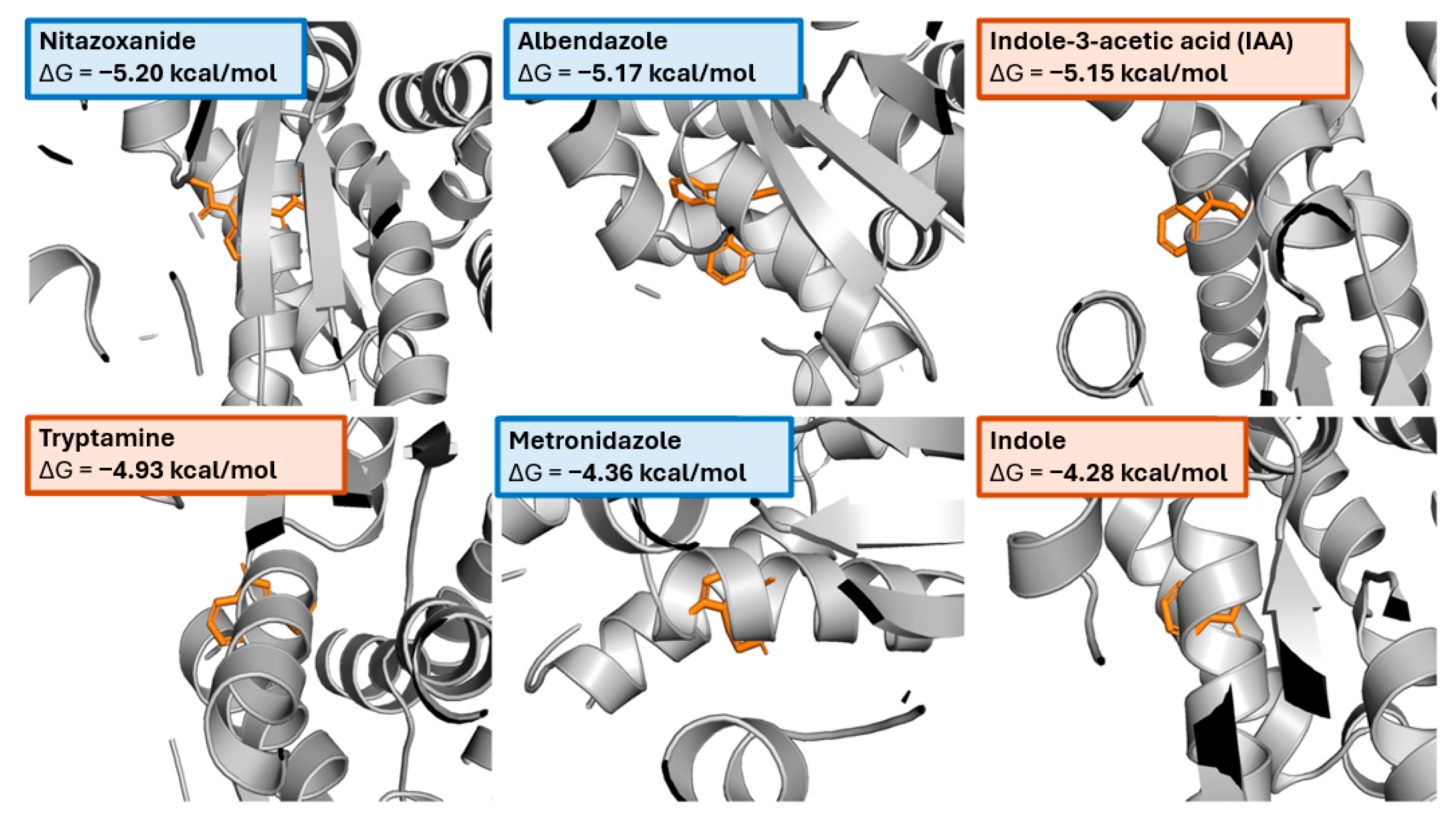

- Indole class (IAA, tryptamine, indole): rich contacts with TYR61–LEU62–LYS63 and GLU67/ALA68, consistent with π-stacking/edge-to-face against TYR61 and H-bonding near GLU67.

- ▪

- Controls: albendazole shows extensive packing (n_contacts = 373) and additional reaches to ASP58/CYS66, while nitazoxanide engages the canonical pocket but also touches residues outside the core (SER57, MET28, GLU71, LEU97), explaining its higher pose dispersion in seed-stability tests.

- ▪

- SCFAs (isovaleric/valeric acids): fewer, more superficial contacts (n_contacts ≈ 120–140) largely limited to MET59–LEU62, in line with their weaker ΔG.

- ▪

- The same hotspot (MET59–ALA68) is engaged by all top ligands, matching the contact heat map and frequency analysis.

- ▪

- Binding depth and ring orientation correlate with ΔG: IAA ≈ albendazole > tryptamine > metronidazole/indole.

- ▪

- The pocket appears aromatic-friendly (π interactions with TYR61) with a polar edge (GLU67) that the indoles exploit efficiently.

- ▪

- Indole family (IAA, tryptamine, indole): common indole ring enabling π-stacking with TYR61 and H-bonding via side-chain donors/acceptors (Fig. panels). IAA’s carboxylate side chain explains its ΔG close to the best controls.

- ▪

- Clinical controls: albendazole (benzimidazole carbamate) and nitazoxanide (thiazolide) are the top scorers; both provide extended aromatic surfaces plus heteroatoms for polar contacts near GLU67/ALA68. Metronidazole/tinidazole (nitroimidazoles) are smaller and bind more shallowly, in line with intermediate ΔG.

- ▪

- SCFAs (isovaleric/valeric): short aliphatic acids lack aromatic surface; they give fewer hydrophobic/π contacts and weaker ΔG.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gardner, T.B.; Hill, D.R. Treatment of Giardiasis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2001, 14, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabay, O.; Tamer, A.; Gunduz, H.; Arinc, H.; Tamer, L. Albendazole versus Metronidazole Treatment of Adult Giardiasis: An Open Randomized Clinical Study. World J. Gastroenterol. 2004, 10, 1215–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solaymani-Mohammadi, S.; Singer, S.M. Giardia duodenalis: The Double-Edged Sword of Immune Responses in Giardiasis. Exp. Parasitol. 2010, 126, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Crystal Structure of Fructose-bisphosphate Aldolase from Giardia lamblia (PDB ID: 3OHI). RCSB Protein Data Bank, 2010. Available online: https://www.rcsb.org/structure/3OHI (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Bäckhed, F. From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, D.J.; Preston, T. Formation of Short Chain Fatty Acids by the Gut Microbiota and Their Impact on Human Metabolism. Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Sperandio, V. Indole Signaling at the Host–Microbiota–Pathogen Interface. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Li, H.; Anjum, K.; Zhong, X.; Miao, S.; Zheng, G.; Liu, W.; Li, L. Dual Role of Indoles Derived from Intestinal Microbiota on Host Health and Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 903526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitchen, D.B.; Decornez, H.; Furr, J.R.; Bajorath, J. Docking and Scoring in Virtual Screening for Drug Discovery: Methods and Applications. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004, 3, 935–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, R. Comparative Assessment of Scoring Functions on a Diverse Test Set. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2009, 49, 1079–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeson, P.D.; Springthorpe, B. The Influence of Drug-Like Concepts on Decision-Making in Medicinal Chemistry. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007, 6, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, H.; Yao, X.; Li, D.; Xu, L.; Li, Y.; Tian, S.; Hou, T. Comprehensive Evaluation of Ten Docking Programs on a Diverse Set of Protein–Ligand Complexes: The Impact of Docking Algorithms, Scoring Functions, and Ligand Flexibility. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2016, 56, 2307–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the Speed and Accuracy of Docking with a New Scoring Function, Efficient Optimization, and Multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga, R.; Villarreal, M.A. Vinardo: A Scoring Function Based on AutoDock Vina Improves Scoring, Docking, and Virtual Screening. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, J.; Santos-Martins, D.; Tillack, A.F.; Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: New Docking Methods, Expanded Force Field, and Python Bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 3891–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Luna, J.; Grisoni, F.; Schneider, G. Drug Discovery with Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2021, 3, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, I.J.; Appleton, G.; Axton, M.; Baak, A.; Blomberg, N.; Boiten, J.-W.; da Silva Santos, L.B.; Bourne, P.E.; et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data Management and Stewardship. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cock, P.J.A.; Antao, T.; Chang, J.T.; Chapman, B.A.; Cox, C.J.; Dalke, A.; Friedberg, I.; Hamelryck, T.; Kauff, F.; Wilczynski, B.; et al. Biopython: Freely Available Python Tools for Computational Molecular Biology and Bioinformatics. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1422–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Boyle, N.M.; Banck, M.; James, C.A.; Morley, C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Hutchison, G.R. Open Babel: An Open Chemical Toolbox. J. Cheminform. 2011, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Lim-Wilby, M. Molecular Docking. Methods Mol. Biol. 2008, 443, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forli, S.; Huey, R.; Pique, M.E.; Sanner, M.F.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. Computational Protein–Ligand Docking and Virtual Drug Screening with the AutoDock Suite. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 905–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLano, W.L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System Version 2.0; DeLano Scientific: San Carlos, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Seeliger, D.; de Groot, B.L. Ligand Docking and Binding Site Analysis with PyMOL and AutoDock/Vina. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2010, 24, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaillard, T. Evaluation of AutoDock and AutoDock Vina on the CASF-2013 Benchmark. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2018, 58, 1697–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossignol, J.F. Nitazoxanide: A First-in-Class Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Agent. Antivir. Res. 2014, 110, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, A.L.; Keserü, G.M.; Leeson, P.D.; Rees, D.C.; Reynolds, C.H. The Role of Ligand Efficiency Metrics in Drug Discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shultz, M.D. Two decades under the influence of the Rule of Five and the changing properties of approved oral drugs. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 1701–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Kokubo, H. Exploring the Stability of Ligand Binding Modes to Proteins by Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2017, 57, 2514–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guterres, H.; Im, W. Improving Protein–Ligand Docking Results with High-Throughput Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60, 2189–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, R.R.; Eckmann, L. Treatment of Giardiasis: Current Status and Future Directions. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2014, 16, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekins, S.; Mestres, J.; Testa, B. In Silico Pharmacology for Drug Discovery: Applications to Targets and Beyond. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 152, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carollo, P.S.; Tutone, M.; Culletta, G.; Fiduccia, I.; Corrao, F.; Pibiri, I.; Di Leonardo, A.; Zizzo, M.G.; Melfi, R.; Pace, A.; et al. Investigating the Inhibition of FTSJ1, a Tryptophan tRNA-Specific 2′-O-Methyltransferase by NV TRIDs, as a Mechanism of Readthrough in Nonsense Mutated CFTR. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

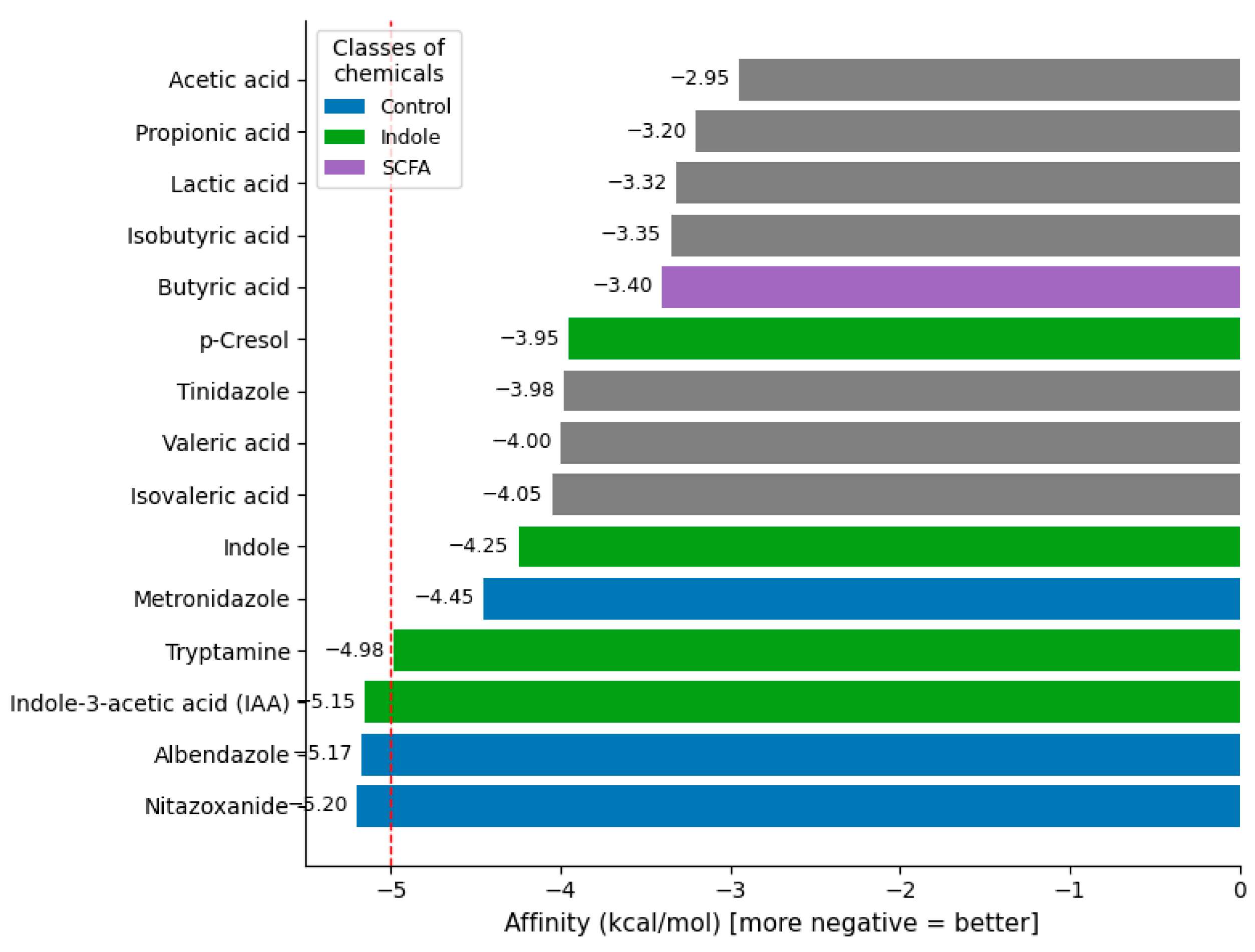

| No. | Ligand | Group | Target | Affinity (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Nitazoxanide | Control | 3OHI | −5.199 |

| 1 | Albendazole | Control | 3OHI | −5.165 |

| 2 | Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) | Indole | 3OHI | −5.147 |

| 3 | Tryptamine | Indole | 3OHI | −4.930 |

| 4 | Metronidazole | Control | 3OHI | −4.363 |

| 5 | Indole | Indole | 3OHI | −4.278 |

| 6 | Isovaleric acid | SCFA | 3OHI | −4.209 |

| 7 | Valeric acid | SCFA | 3OHI | −4.111 |

| 8 | Tinidazole | Control | 3OHI | −4.035 |

| 9 | p-Cresol | Aromatic | 3OHI | −4.021 |

| 10 | Butyric acid | SCFA | 3OHI | −3.620 |

| 11 | Isobutyric acid | SCFA | 3OHI | −3.533 |

| 12 | Lactic acid | Microbiome | 3OHI | −3.501 |

| 13 | Propionic acid | SCFA | 3OHI | −3.225 |

| 14 | Acetic acid | SCFA | 3OHI | −2.909 |

| No. | Ligand | Group | Target | Affinity (kcal/mol) | pKd (Approx.) | LE (kcal/mol per Heavy Atom) | LLE (approx.) | MolWt (g/mol) | Heavy Atoms | HBD | HBA | TPSA (Å2) | RotB | LogP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Nitazoxanide | Control | 3OHI | −5.199 | 3.811 | 0.2266 | 1.1549 | 336.0625 | 23 | 3 | 6 | 113.44 | 6 | 2.6563 |

| 1 | Albendazole | Control | 3OHI | −5.165 | 3.786 | 0.2247 | −0.5200 | 329.0931 | 24 | 2 | 4 | 65.15 | 5 | 4.3060 |

| 2 | Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) | Indole | 3OHI | −5.147 | 3.773 | 0.3959 | 1.9782 | 175.0633 | 13 | 2 | 2 | 53.09 | 2 | 1.7950 |

| 3 | Tryptamine | Indole | 3OHI | −4.930 | 3.611 | 0.4108 | 1.9449 | 160.1000 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 41.81 | 3 | 1.6691 |

| 4 | Metronidazole | Control | 3OHI | −4.363 | 3.193 | 0.3564 | 3.7092 | 173.0437 | 15 | 2 | 5 | 101.42 | 5 | −0.5180 |

| 5 | Indole | Indole | 3OHI | −4.278 | 3.138 | 0.4753 | 0.9628 | 117.875 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 41.79 | 1 | 2.1400 |

| 6 | Isovaleric acid | SCFA | 3OHI | −4.209 | 3.085 | 0.5813 | 1.9684 | 102.0680 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 37.30 | 4 | 1.1171 |

| 7 | Valeric acid | SCFA | 3OHI | −4.111 | 3.016 | 0.5162 | 1.7525 | 102.0680 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 37.30 | 4 | 1.1749 |

| 8 | Tinidazole | Control | 3OHI | −4.035 | 2.959 | 0.2690 | 1.1525 | 249.0242 | 18 | 2 | 5 | 81.19 | 8 | 0.8566 |

| 9 | p-Cresol | Aromatic | 3OHI | −4.021 | 2.947 | 0.5026 | 2.4375 | 108.0575 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 20.23 | 2 | 2.2192 |

| 10 | Butyric acid | SCFA | 3OHI | −3.620 | 2.654 | 0.6033 | 1.7827 | 88.0504 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 37.30 | 3 | 0.8700 |

| 11 | Isobutyric acid | SCFA | 3OHI | −3.533 | 2.589 | 0.5889 | 1.8629 | 88.0504 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 37.30 | 3 | 0.7270 |

| 12 | Lactic acid | Microbiome | 3OHI | −3.501 | 2.567 | 0.5855 | 3.1742 | 90.0316 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 57.53 | 3 | −0.5840 |

| 13 | Propionic acid | SCFA | 3OHI | −3.225 | 2.366 | 0.6460 | 1.7665 | 74.0368 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 37.30 | 3 | 0.8900 |

| 14 | Acetic acid | SCFA | 3OHI | −2.909 | 2.133 | 0.7273 | 2.0416 | 60.0211 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 37.30 | 3 | 1.0900 |

| No. | Ligand | Vina (kcal/mol) | Vinardo (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nitazoxanide | −4.433 | −3.175 |

| 2 | Albendazole | −5.198 | −3.524 |

| 3 | Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) | −5.107 | −4.212 |

| 4 | Tryptamine | −4.912 | −4.340 |

| 5 | Metronidazole | −4.203 | −3.022 |

| 6 | Indole | −4.271 | −3.613 |

| 7 | Isovaleric acid | −3.302 | −2.989 |

| 8 | Valeric acid | −3.343 | −3.968 |

| 9 | Tinidazole | −3.997 | −3.175 |

| 10 | p-Cresol | −4.022 | −3.671 |

| No. | Ligand | Mean ΔG (kcal/mol) | SD (kcal/mol) | n (Replicates) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Albendazole | −5.159 | 0.00497 | 3 |

| 2 | Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) | −5.138 | 0.00680 | 3 |

| 3 | Tryptamine | −4.922 | 0.01034 | 3 |

| 4 | Nitazoxanide | −4.584 | 0.43520 | 3 |

| 5 | Metronidazole | −4.270 | 0.05361 | 3 |

| Index | Ligand | Group | ΔG (kcal/mol) | No. of Contacts | Residues Contacted (Chain: Residue) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Nitazoxanide | Control | −5.199 | 345 | MET28:B, SER57:A, MET59:A, ILE60:A, TYR61:A, LEU62:A, LYS63:A, LYS64:A, LEU65:B, GLU67:A, LEU97:A |

| 1 | Albendazole | Control | −5.165 | 373 | ASP58:A, ILE60:A, TYR61:A, LEU62:A, LYS63:A, LYS64:A, LEU65:B, CYS66:A, GLU67:A, ALA68:B |

| 2 | Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) | Indole | −5.147 | 235 | MET59:A, ILE60:A, TYR61:A, LEU62:A, LYS63:A, LYS64:A, LEU65:B, CYS66:A, GLU67:A |

| 3 | Tryptamine | Indole | −4.930 | 209 | MET59:A, ILE60:A, TYR61:A, LEU62:A, LYS63:A, LYS64:A, LEU65:B, GLU67:A |

| 4 | Metronidazole | Control | −4.363 | 232 | MET59:A, ILE60:A, TYR61:A, LEU62:A, LYS63:A, LYS64:A, LEU65:A, CYS66:A, GLU67:A |

| 5 | Indole | Indole | −4.278 | 173 | MET59:A, ILE60:A, TYR61:A, LEU62:A, LYS63:A, LYS64:A, LEU65:A, GLU67:A |

| 6 | Isovaleric acid | SCFA | −4.209 | 137 | MET59:A, ILE60:A, TYR61:A, LEU62:A, LYS63:A, LYS64:A, LEU65:A |

| 7 | Valeric acid | SCFA | −4.111 | 122 | MET59:A, ILE60:A, TYR61:A, LEU62:A, LYS63:A, LYS64:A, LEU65:A, LEU65:B |

| 8 | Tinidazole | Control | −4.035 | 140 | ILE31:A, MET59:A, TYR61:A, LEU62:A, LYS63:A, LYS64:A, LEU65:A, GLU67:A, ALA68:B |

| 9 | p-Cresol | Aromatic | −4.021 | 148 | MET59:A, ILE60:A, TYR61:A, LEU62:A, LYS63:A, LYS64:A, LEU65:A, GLU67:A |

| Residue (Chain:ID) | Frequency in Top-N Ligands |

|---|---|

| TYR61:A | 10 |

| ILE60:A | 10 |

| MET59:A | 10 |

| LYS63:A | 10 |

| LYS64:A | 10 |

| LEU65:A | 10 |

| LEU62:A | 10 |

| GLU67:A | 8 |

| ALA68:B | 6 |

| LEU65:B | 5 |

| LYS64:B | 5 |

| CYS66:A | 3 |

| ASP58:A | 1 |

| ILE31:A | 1 |

| SER57:A | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Condori Mamani, A.B.; Rivera Prado, A.B.; Yparraguirre Salcedo, K.G.; Lozano, L.L.; Chambilla Quispe, V.F.; Ramirez Atencio, C.W. Microbiome Indoles Dock at the TYR61–GLU67 Hotspot of Giardia lamblia FBPA: Evidence from Docking, Rescoring, and Contact Mapping. Appl. Microbiol. 2026, 6, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol6020023

Condori Mamani AB, Rivera Prado AB, Yparraguirre Salcedo KG, Lozano LL, Chambilla Quispe VF, Ramirez Atencio CW. Microbiome Indoles Dock at the TYR61–GLU67 Hotspot of Giardia lamblia FBPA: Evidence from Docking, Rescoring, and Contact Mapping. Applied Microbiology. 2026; 6(2):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol6020023

Chicago/Turabian StyleCondori Mamani, Angelica Beatriz, Anthony Brayan Rivera Prado, Kelly Geraldine Yparraguirre Salcedo, Luis Lloja Lozano, Vicente Freddy Chambilla Quispe, and Claudio Willbert Ramirez Atencio. 2026. "Microbiome Indoles Dock at the TYR61–GLU67 Hotspot of Giardia lamblia FBPA: Evidence from Docking, Rescoring, and Contact Mapping" Applied Microbiology 6, no. 2: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol6020023

APA StyleCondori Mamani, A. B., Rivera Prado, A. B., Yparraguirre Salcedo, K. G., Lozano, L. L., Chambilla Quispe, V. F., & Ramirez Atencio, C. W. (2026). Microbiome Indoles Dock at the TYR61–GLU67 Hotspot of Giardia lamblia FBPA: Evidence from Docking, Rescoring, and Contact Mapping. Applied Microbiology, 6(2), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol6020023