How the Microbiome Affects Canine Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Dental

3. Cardiac Disease

4. Gut Microbiome

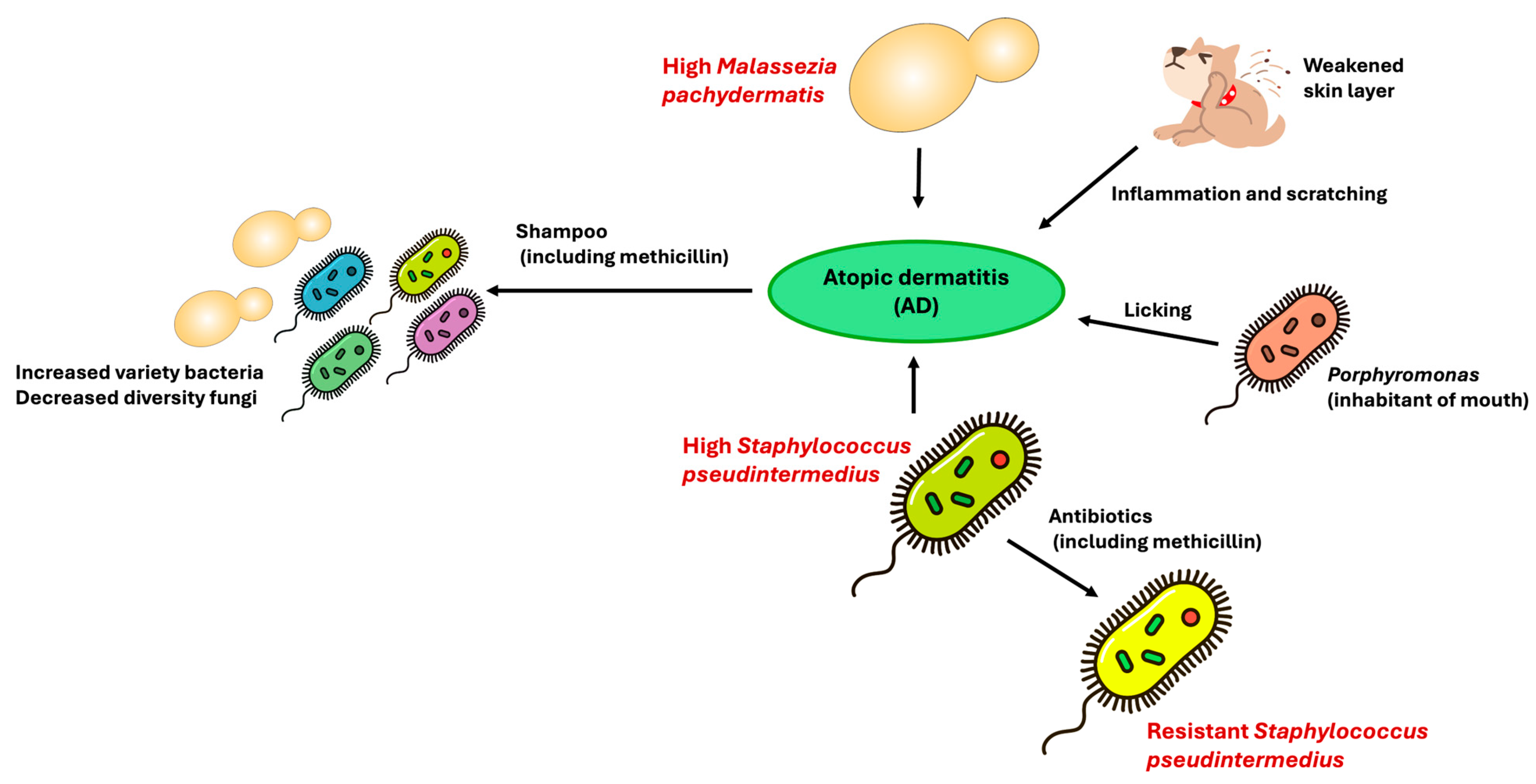

5. Skin

6. Renal

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

List of Abbreviations

| AD | Atopic Dermatitis |

| CHF | Congestive Heart Failure |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| CVHD | Chronic Valvular Heart Disease |

| GI | Gingival Index |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| PD | Periodontal Disease |

| SCFAs | Short-Chain Fatty Acids |

| TMA | Trimethylamine |

| TMAO | Trimethylamine N-oxide |

| TSLP | Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin |

References

- Boon, E.; Meehan, C.J.; Whidden, C.; Wong, D.H.-J.; Langille, M.G.I.; Beiko, R.G. Interactions in the Microbiome: Communities of Organisms and Communities of Genes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 38, 90–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.-X.; Chen, X.-Y.; Wang, J.-Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in Health and Diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira Dos Santos, J.D.; Cunha, E.; Nunes, T.; Tavares, L.; Oliveira, M. Relation between Periodontal Disease and Systemic Diseases in Dogs. Res. Vet. Sci. 2019, 125, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Pinteño, A.; Pilla, R.; Suchodolski, J.; Apper, E.; Torre, C.; Salas-Mani, A.; Manteca, X. Age-Related Changes in Gut Health and Behavioral Biomarkers in a Beagle Dog Population. Animals 2025, 15, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AL-Amrah, H.; Aburokba, R.; Alotiby, A.; AlJuhani, B.; Huri, H.; Garni, N.A. The Impact of Dogs Oral Microbiota on Human Health: A Review. Biosci. Biotechnol. Res. Asia 2024, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, C.; Holcombe, L.J. A Review of the Frequency and Impact of Periodontal Disease in Dogs. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2020, 61, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löe, H. The Gingival Index, the Plaque Index and the Retention Index Systems. J. Periodontol. 1967, 38, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, J.L.; Bauer, A.E.; Croney, C.C. A Cross-Sectional Study to Estimate Prevalence of Periodontal Disease in a Population of Dogs (Canis familiaris) in Commercial Breeding Facilities in Indiana and Illinois. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.Y.; Darveau, R.; Kaeberlein, M. Oral Health in Geroscience: Animal Models and the Aging Oral Cavity. GeroScience 2018, 40, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, M.D.; Wallis, C.V.; Milella, L.; Colyer, A.; Tweedie, A.D.; Harris, S. A Longitudinal Assessment of Periodontal Disease in 52 Miniature Schnauzers. BMC Vet. Res. 2014, 10, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruparell, A.; Wallis, C.; Haydock, R.; Cawthrow, A.; Holcombe, L.J. Comparison of Subgingival and Gingival Margin Plaque Microbiota from Dogs with Healthy Gingiva and Early Periodontal Disease. Res. Vet. Sci. 2021, 136, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santibáñez, R.; Rodríguez-Salas, C.; Flores-Yáñez, C.; Garrido, D.; Thomson, P. Assessment of Changes in the Oral Microbiome That Occur in Dogs with Periodontal Disease. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bello, A.; Buonavoglia, A.; Franchini, D.; Valastro, C.; Ventrella, G.; Greco, M.F.; Corrente, M. Periodontal Disease Associated with Red Complex Bacteria in Dogs. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2014, 55, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niemiec, B.A.; Gawor, J.; Tang, S.; Prem, A.; Krumbeck, J.A. The Bacteriome of the Oral Cavity in Healthy Dogs and Dogs with Periodontal Disease. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2022, 83, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwack, K.H.; Jang, E.Y.; Kim, C.; Choi, Y.S.; Lee, J.H.; Moon, J.H. Porphyromonas gulae and canine periodontal disease: Current understanding and future directions. Virulence 2025, 16, 2449019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, J.L.; Ley, R.E. The Human Gut Bacteria Christensenellaceae Are Widespread, Heritable, and Associated with Health. BMC Biol. 2019, 17, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadê-Neto, C.R.; Rodrigues, R.R.; Louzada, L.M.; Arruda-Vasconcelos, R.; Teixeira, F.B.; Viana Casarin, R.C.; Gomes, B.P.F.A. Microbiota of Periodontal Pockets and Root Canals in Induced Experimental Periodontal Disease in Dogs. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2019, 10, e12439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruyama, N.; Mori, A.; Shono, S.; Oda, H.; Sako, T. Evaluation of changes in periodontal bacteria in healthy dogs over 6 months using quantitative real-time PCR. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2018, 21, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glickman, L.T.; Glickman, N.W.; Moore, G.E.; Goldstein, G.S.; Lewis, H.B. Evaluation of the Risk of Endocarditis and Other Cardiovascular Events on the Basis of the Severity of Periodontal Disease in Dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2009, 234, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, C.; Bonagura, J.; Ettinger, S.; Fox, P.; Gordon, S.; Haggstrom, J.; Hamlin, R.; Keene, B.; Luis-Fuentes, V.; Stepien, R. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Canine Chronic Valvular Heart Disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2009, 23, 1142–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, A.; French, A.T.; Dukes-McEwan, J.; Corcoran, B.M. Ultrastructural Morphologic Evaluation of the Phenotype of Valvular Interstitial Cells in Dogs with Myxomatous Degeneration of the Mitral Valve. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2005, 66, 1408–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, R.I.; Black, A.; Culshaw, G.J.; French, A.T.; Else, R.W.; Corcoran, B.M. Distribution of Myofibroblasts, Smooth Muscle–like Cells, Macrophages, and Mast Cells in Mitral Valve Leaflets of Dogs with Myxomatous Mitral Valve Disease. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2008, 69, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadian, M.; Corcoran, B.M.; Han, R.I.; Grossmann, J.G.; Bradshaw, J.P. Collagen Organization in Canine Myxomatous Mitral Valve Disease: An X-Ray Diffraction Study. Biophys. J. 2007, 93, 2472–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corcoran, B.M.; Black, A.; Anderson, H.; McEwan, J.D.; French, A.; Smith, P.; Devine, C. Identification of Surface Morphologic Changes in the Mitral Valve Leaflets and Chordae Tendineae of Dogs with Myxomatous Degeneration. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2004, 65, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, L.H.; Fredholm, M.; Pedersen, H.D. Epidemiology and Inheritance of Mitral Valve Prolapse in Dachshunds. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 1999, 13, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mow, T.; Pedersen, H.D. Increased Endothelin-Receptor Density in Myxomatous Canine Mitral Valve Leaflets. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1999, 34, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, E.; Gring, C.N.; Griffin, B.P. Mitral Valve Prolapse. Lancet 2005, 365, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Previti, A.; Biondi, V.; Passantino, A.; Or, M.E.; Pugliese, M. Canine Bacterial Endocarditis: A Text Mining and Topics Modeling Analysis as an Approach for a Systematic Review. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reagan, K.L.; Visser, L.C.; Epstein, S.E.; Stern, J.A.; Johnson, L.R. Outcome and Prognostic Factors in Infective Endocarditis in Dogs: 113 Cases (2005–2020). J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2022, 36, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlez, K.; Eisenberg, T.; Rau, J.; Dubielzig, S.; Kornmayer, M.; Wolf, G.; Berger, A.; Dangel, A.; Hoffmann, C.; Ewers, C.; et al. Corynebacterium Rouxii, a Recently Described Member of the C. Diphtheriae Group Isolated from Three Dogs with Ulcerative Skin Lesions. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 2021, 114, 1361–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tresch, M.; Watté, C.; Stengard, M.; Ritter, C.; Brodard, I.; Feyer, S.; Gohl, E.; Akdesir, E.; Perreten, V.; Kittl, S. Corynebacterium Oculi-Related Bacterium May Act as a Pathogen and Carrier of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Dogs: A Case Report. BMC Vet. Res. 2023, 19, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reboli, A.C.; Farrar, W.E. Erysipelothrix Rhusiopathiae: An Occupational Pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1989, 2, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.T.G.D.; Souza, A.M.D.; Campos, S.D.E.; Macieira, D.D.B.; Lemos, E.R.S.D.; Favacho, A.R.D.M.; Almosny, N.R.P. Bartonella Henselae and Bartonella Clarridgeiae Infection, Hematological Changes and Associated Factors in Domestic Cats and Dogs from an Atlantic Rain Forest Area, Brazil. Acta Trop. 2019, 193, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambon, J.J. Actinobacillus Actinomycetemcomitans in Human Periodontal Disease. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1985, 12, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, J.E.; Kittleson, M.D.; Pesavento, P.A.; Byrne, B.A.; MacDonald, K.A.; Chomel, B.B. Evaluation of the Relationship between Causative Organisms and Clinical Characteristics of Infective Endocarditis in Dogs: 71 Cases (1992–2005). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2006, 228, 1723–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, J.; Matthewman, L.; Xia, D.; Wilshaw, J.; Chang, Y.-M.; Connolly, D.J. The Gut Microbiome in Dogs with Congestive Heart Failure: A Pilot Study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oršolić, N.; Knežević, A.H.; Šver, L.; Terzić, S.; Bašić, I. Immunomodulatory and Antimetastatic Action of Propolis and Related Polyphenolic Compounds. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 94, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schober, K.E.; Hart, T.M.; Stern, J.A.; Li, X.; Samii, V.F.; Zekas, L.J.; Scansen, B.A.; Bonagura, J.D. Detection of Congestive Heart Failure in Dogs by Doppler Echocardiography: Congestive Heart Failure in Dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2010, 24, 1358–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasini, E.; Aquilani, R.; Testa, C.; Baiardi, P.; Angioletti, S.; Boschi, F.; Verri, M.; Dioguardi, F. Pathogenic Gut Flora in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2016, 4, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Baeza, Y.; Hyde, E.R.; Suchodolski, J.S.; Knight, R. Dog and Human Inflammatory Bowel Disease Rely on Overlapping yet Distinct Dysbiosis Networks. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 16177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, X.C.; Tickle, T.L.; Sokol, H.; Gevers, D.; Devaney, K.L.; Ward, D.V.; Reyes, J.A.; Shah, S.A.; LeLeiko, N.; Snapper, S.B.; et al. Dysfunction of the Intestinal Microbiome in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Treatment. Genome Biol. 2012, 13, R79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlin, E.T.; Rush, J.E.; Freeman, L.M. A Pilot Study Investigating Circulating Trimethylamine N-oxide and Its Precursors in Dogs with Degenerative Mitral Valve Disease with or without Congestive Heart Failure. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2019, 33, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeisel, S.H.; Warrier, M. Trimethylamine N-Oxide, the Microbiome, and Heart and Kidney Disease. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2017, 37, 157–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janeiro, M.; Ramírez, M.; Milagro, F.; Martínez, J.; Solas, M. Implication of Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) in Disease: Potential Biomarker or New Therapeutic Target. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilla, R.; Suchodolski, J.S. The Role of the Canine Gut Microbiome and Metabolome in Health and Gastrointestinal Disease. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 6, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, K.E.; Pfaffinger, J.M.; Ryznar, R. The Interplay between Gut Microbiota, Short-Chain Fatty Acids, and Implications for Host Health and Disease. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2393270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, H.; Trivedi, M.; Gurjar, T.; Sahoo, D.K.; Jergens, A.E.; Yadav, V.K.; Patel, A.; Pandya, P. Decoding the Gut Microbiome in Companion Animals: Impacts and Innovations. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mahony, S.M.; Clarke, G.; Borre, Y.E.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Serotonin, Tryptophan Metabolism and the Brain-Gut-Microbiome Axis. Behav. Brain Res. 2015, 277, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honneffer, J.B.; Steiner, J.M.; Lidbury, J.A.; Suchodolski, J.S. Variation of the Microbiota and Metabolome along the Canine Gastrointestinal Tract. Metabolomics 2017, 13, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magne, F.; Gotteland, M.; Gauthier, L.; Zazueta, A.; Pesoa, S.; Navarrete, P.; Balamurugan, R. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio: A Relevant Marker of Gut Dysbiosis in Obese Patients? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, F.; Hehemann, J.-H.; Rebuffet, E.; Czjzek, M.; Michel, G. Environmental and Gut Bacteroidetes: The Food Connection. Front. Microbiol. 2011, 2, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, N.-R.; Whon, T.W.; Bae, J.-W. Proteobacteria: Microbial Signature of Dysbiosis in Gut Microbiota. Trends Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groussin, M.; Mazel, F.; Sanders, J.G.; Smillie, C.S.; Lavergne, S.; Thuiller, W.; Alm, E.J. Unraveling the Processes Shaping Mammalian Gut Microbiomes over Evolutionary Time. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, G.; Hagen-Plantinga, E.A.; Hendriks, W.H. Dietary Nutrient Profiles of Wild Wolves: Insights for Optimal Dog Nutrition? Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, S40–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L.M.; Chandler, M.L.; Hamper, B.A.; Weeth, L.P. Current Knowledge about the Risks and Benefits of Raw Meat–Based Diets for Dogs and Cats. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2013, 243, 1549–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, R.H.; Lawes, J.R.; Wales, A.D. Raw Diets for Dogs and Cats: A Review, with Particular Reference to Microbiological Hazards. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2019, 60, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finley, R.; Ribble, C.; Aramini, J.; Vandermeer, M.; Popa, M.; Litman, M.; Reid-Smith, R. The Risk of Salmonellae Shedding by Dogs Fed Salmonella-Contaminated Commercial Raw Food Diets. Can. Vet. J. Rev. Vet. Can. 2007, 48, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Hellgren, J.; Hästö, L.S.; Wikström, C.; Fernström, L.; Hansson, I. Occurrence of Salmonella, Campylobacter, Clostridium and Enterobacteriaceae in Raw Meat-based Diets for Dogs. Vet. Rec. 2019, 184, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix, A.P.; Souza, C.M.M.; De Oliveira, S.G. Biomarkers of Gastrointestinal Functionality in Dogs: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2022, 283, 115183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaglio, A.E.V.; Grillo, T.G.; Oliveira, E.C.S.D.; Stasi, L.C.D.; Sassaki, L.Y. Gut Microbiota, Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Colorectal Cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 4053–4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jergens, A.E.; Guard, B.C.; Redfern, A.; Rossi, G.; Mochel, J.P.; Pilla, R.; Chandra, L.; Seo, Y.-J.; Steiner, J.M.; Lidbury, J.; et al. Microbiota-Related Changes in Unconjugated Fecal Bile Acids Are Associated With Naturally Occurring, Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus in Dogs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sancak, A.A.; Rutgers, H.C.; Hart, C.A.; Batt, R.M. Prevalence of Enteropathic Escherichia Coli in Dogs with Acute and Chronic Diarrhoea. Vet. Rec. 2004, 154, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cani, P.D.; Bibiloni, R.; Knauf, C.; Waget, A.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Delzenne, N.M.; Burcelin, R. Changes in Gut Microbiota Control Metabolic Endotoxemia-Induced Inflammation in High-Fat Diet–Induced Obesity and Diabetes in Mice. Diabetes 2008, 57, 1470–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnauck, A.; Lentle, R.G.; Kruger, M.C. The Characteristics and Function of Bacterial Lipopolysaccharides and Their Endotoxic Potential in Humans. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 35, 189–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, J.; Guarner, F.; Bustos Fernandez, L.; Maruy, A.; Sdepanian, V.L.; Cohen, H. Antibiotics as Major Disruptors of Gut Microbiota. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 572912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Mazcorro, J.F.; Suchodolski, J.S.; Jones, K.R.; Clark-Price, S.C.; Dowd, S.E.; Minamoto, Y.; Markel, M.; Steiner, J.M.; Dossin, O. Effect of the Proton Pump Inhibitor Omeprazole on the Gastrointestinal Bacterial Microbiota of Healthy Dogs. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2012, 80, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilla, R.; Gaschen, F.P.; Barr, J.W.; Olson, E.; Honneffer, J.; Guard, B.C.; Blake, A.B.; Villanueva, D.; Khattab, M.R.; AlShawaqfeh, M.K.; et al. Effects of Metronidazole on the Fecal Microbiome and Metabolome in Healthy Dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2020, 34, 1853–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, D.A.; Noble, P.J.M.; Sánchez-Vizcaíno, F.; Dawson, S.; Pinchbeck, G.L.; Williams, N.J.; Radford, A.D.; Jones, P.H. Pharmaceutical Prescription in Canine Acute Diarrhoea: A Longitudinal Electronic Health Record Analysis of First Opinion Veterinary Practices. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chermprapai, S.; Ederveen, T.H.A.; Broere, F.; Broens, E.M.; Schlotter, Y.M.; Van Schalkwijk, S.; Boekhorst, J.; Van Hijum, S.A.F.T.; Rutten, V.P.M.G. The Bacterial and Fungal Microbiome of the Skin of Healthy Dogs and Dogs with Atopic Dermatitis and the Impact of Topical Antimicrobial Therapy, an Exploratory Study. Vet. Microbiol. 2019, 229, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadlec, K.; Schwarz, S. Antimicrobial Resistance of Staphylococcus Pseudintermedius. Vet. Dermatol. 2012, 23, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Both, M.; Csukai, M.; Stumpf, M.P.H.; Spanu, P.D. Gene Expression Profiles of Blumeria Graminis Indicate Dynamic Changes to Primary Metabolism during Development of an Obligate Biotrophic Pathogen. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 2107–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues Hoffmann, A.; Patterson, A.P.; Diesel, A.; Lawhon, S.D.; Ly, H.J.; Stephenson, C.E.; Mansell, J.; Steiner, J.M.; Dowd, S.E.; Olivry, T.; et al. The Skin Microbiome in Healthy and Allergic Dogs. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e83197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixit, A.B.; Lewis, W.H.; Wedner, H.J. The Allergens of Epicoccum Nigrum Link. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1992, 90, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, D.; Marsella, R.; Pucheu-Haston, C.M.; Eisenschenk, M.N.C.; Nuttall, T.; Bizikova, P. Review: Pathogenesis of Canine Atopic Dermatitis: Skin Barrier and Host–Micro-organism Interaction. Vet. Dermatol. 2015, 26, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chermprapai, S.; Broere, F.; Gooris, G.; Schlotter, Y.M.; Rutten, V.P.M.G.; Bouwstra, J.A. Altered Lipid Properties of the Stratum Corneum in Canine Atopic Dermatitis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Biomembr. 2018, 1860, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsella, R. Atopic Dermatitis in Domestic Animals: What Our Current Understanding Is and How This Applies to Clinical Practice. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivry, T.; Dunston, S.M. Expression Patterns of Superficial Epidermal Adhesion Molecules in an Experimental Dog Model of Acute Atopic Dermatitis Skin Lesions. Vet. Dermatol. 2015, 26, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobiella, D.; Archer, L.; Bohannon, M.; Santoro, D. Pilot Study Using Five Methods to Evaluate Skin Barrier Function in Healthy Dogs and in Dogs with Atopic Dermatitis. Vet. Dermatol. 2019, 30, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-R.; Kim, S.-M.; Kim, J.-H. A Pilot Study of Alterations of the Gut Microbiome in Canine Chronic Kidney Disease. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1241215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipov, A.; Shahar, R.; Sugar, N.; Segev, G. The Influence of Chronic Kidney Disease on the Structural and Mechanical Properties of Canine Bone. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2018, 32, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartges, J.W. Chronic Kidney Disease in Dogs and Cats. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2012, 42, 669–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohia, S.; Vlahou, A.; Zoidakis, J. Microbiome in Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD): An Omics Perspective. Toxins 2022, 14, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchodolski, J.S. Analysis of the Gut Microbiome in Dogs and Cats. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2022, 50, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Rodriguez, E.; Fernandez-Prado, R.; Esteras, R.; Perez-Gomez, M.V.; Gracia-Iguacel, C.; Fernandez-Fernandez, B.; Kanbay, M.; Tejedor, A.; Lazaro, A.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.; et al. Impact of Altered Intestinal Microbiota on Chronic Kidney Disease Progression. Toxins 2018, 10, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jazani, N.H.; Savoj, J.; Lustgarten, M.; Lau, W.L.; Vaziri, N.D. Impact of Gut Dysbiosis on Neurohormonal Pathways in Chronic Kidney Disease. Diseases 2019, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzatti, G.; Lopetuso, L.R.; Gibiino, G.; Binda, C.; Gasbarrini, A. Proteobacteria: A Common Factor in Human Diseases. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 9351507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Lim, S.Y.; Ko, Y.S.; Lee, H.Y.; Oh, S.W.; Kim, M.G.; Cho, W.Y.; Jo, S.K. Intestinal Barrier Disruption and Dysregulated Mucosal Immunity Contribute to Kidney Fibrosis in Chronic Kidney Disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2019, 34, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, C.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, D. Molecular Pathogenesis of Klebsiella Pneumoniae. Future Microbiol. 2014, 9, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikuchi, M.; Ueno, M.; Itoh, Y.; Suda, W.; Hattori, M. Uremic Toxin-Producing Gut Microbiota in Rats with Chronic Kidney Disease. Nephron 2017, 135, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Arango, L.F.; Barrett, H.L.; Wilkinson, S.A.; Callaway, L.K.; McIntyre, H.D.; Morrison, M.; Dekker Nitert, M. Low Dietary Fiber Intake Increases Collinsella Abundance in the Gut Microbiota of Overweight and Obese Pregnant Women. Gut Microbes 2018, 9, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukavina Mikusic, N.L.; Kouyoumdzian, N.M.; Choi, M.R. Gut Microbiota and Chronic Kidney Disease: Evidences and Mechanisms That Mediate a New Communication in the Gastrointestinal-Renal Axis. Pflügers Arch.-Eur. J. Physiol. 2020, 472, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Organism | Categorization | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Porphyromonas gingivalis | Anaerobic, Gram-negative | Found in mouth, urogenital tract, and gastrointestinal tract. Can cause swelling and infection. |

| Tannerella forsythia | Anaerobic, Gram-negative | A member of Bacteroidota phylum and part of red complex of periodontal pathogens. Associated with increased risk of esophageal cancer. |

| Actinomyces sp. | Anaerobic, Gram-positive | Filamentous and branching; Pleiomorphic. Enter via mucosal membranes, especially oral, and cause opportunistic infection |

| Treponema denticola | Anaerobic, Gram-negative | Highly proteolytic spirochaete |

| Christensenella sp. | Anaerobic, Gram-negative | Non-spore forming, nonmotile bacteria that is known as healthy part of human gut microbiota but found as part of periodontal disease-causing oral biofilms in dogs |

| Methanobrevibacter oralis | Anaerobic, Gram-positive | Methanogenic archaeon mainly associated with oral cavity. Coccobacillus shaped and non-motile |

| Peptostreptococcus canis | Anaerobic, Gram-positive | Coccus bacterius in the subgingival plaque of dogs |

| Campylobacter rectus | Facultative Anaerobe, Gram-negative | Pathogen in chronic periodontitis and can induce bone loss |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Graham Valbuena, M.; Esposito, M.M. How the Microbiome Affects Canine Health. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 5, 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040148

Graham Valbuena M, Esposito MM. How the Microbiome Affects Canine Health. Applied Microbiology. 2025; 5(4):148. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040148

Chicago/Turabian StyleGraham Valbuena, Mariah, and Michelle Marie Esposito. 2025. "How the Microbiome Affects Canine Health" Applied Microbiology 5, no. 4: 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040148

APA StyleGraham Valbuena, M., & Esposito, M. M. (2025). How the Microbiome Affects Canine Health. Applied Microbiology, 5(4), 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040148