Influence of Dissolved Oxygen on the Pseudomonas aeruginosa 6K-11 Rhamnolipid Production

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strain Reactivation and Scale-Up

2.2. Evaluation of Bacterial Growth

2.3. Dissolved Oxygen (DO) Concentration Monitoring

2.4. Monitoring of Rhamnolipid (RL) Production

2.5. Purification of Rhamnolipids

2.6. Rhamnolipids Quantification

2.7. Effect of Aeration on Dissolved Oxygen and RL Production

2.8. Effect of Agitation on DO and RL Production

2.9. Influence of Sodium Nitrate Concentration on RL Production

2.10. Determination of Critical Micelle Concentration

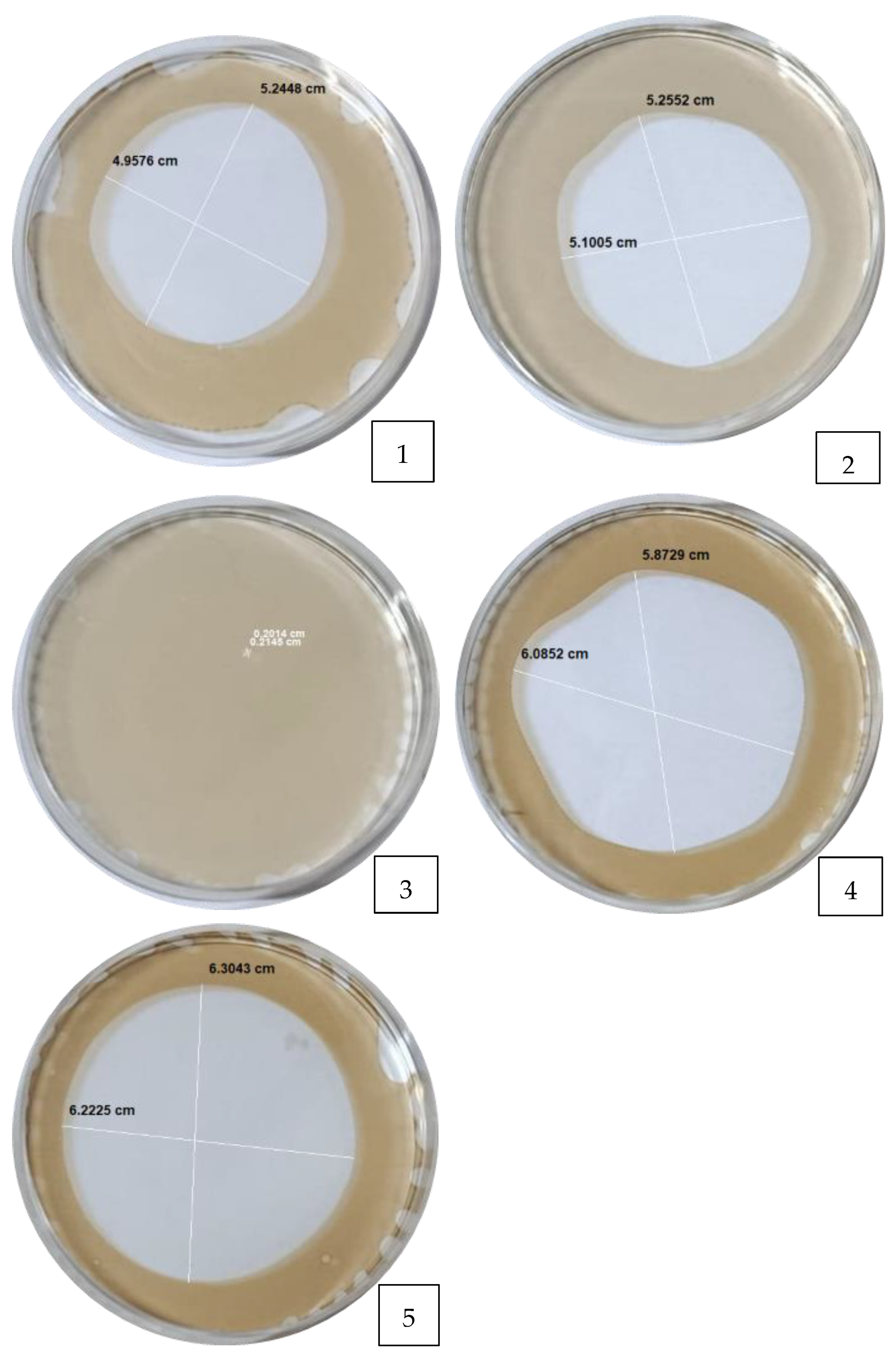

2.11. Oil Spreading Activity

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

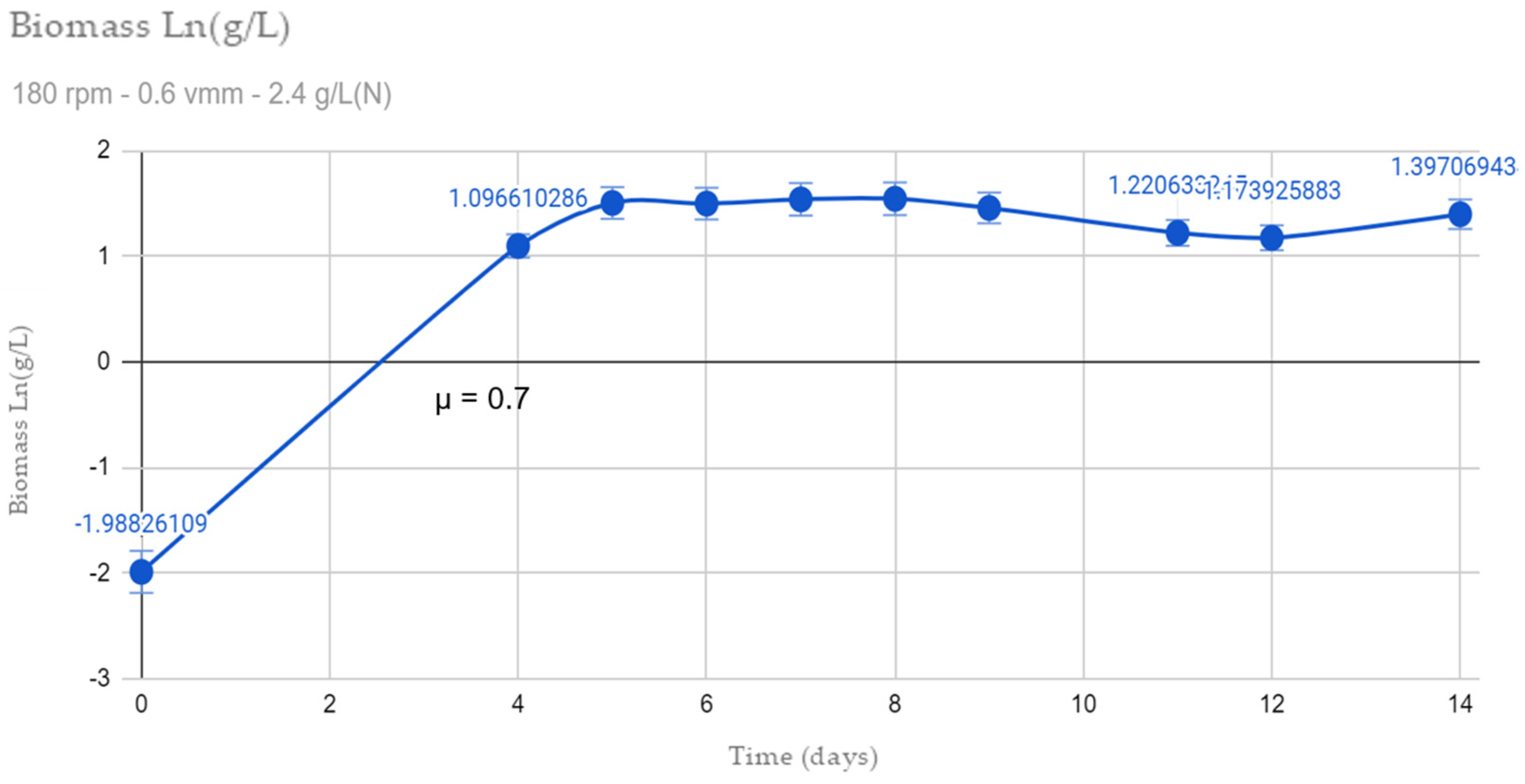

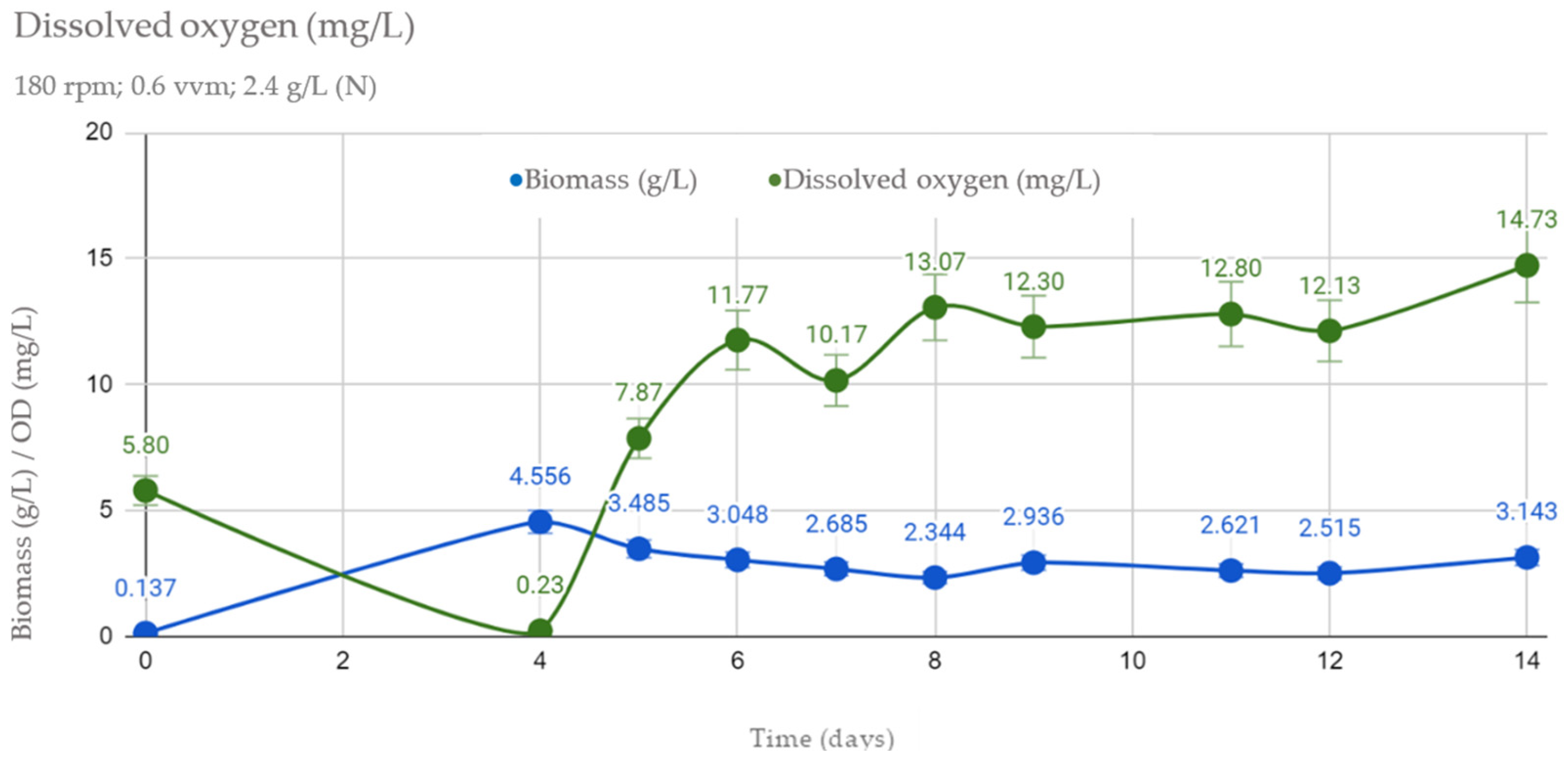

3.1. Growth Kinetics

3.2. Dissolved Oxygen Concentration (DO)

3.3. Experimental Design and Predictive Model for Rhamnolipid Production

3.4. Model Reliability

3.5. Influence of Aeration Rate, Agitation Speed and Sodium Nitrate Concentration

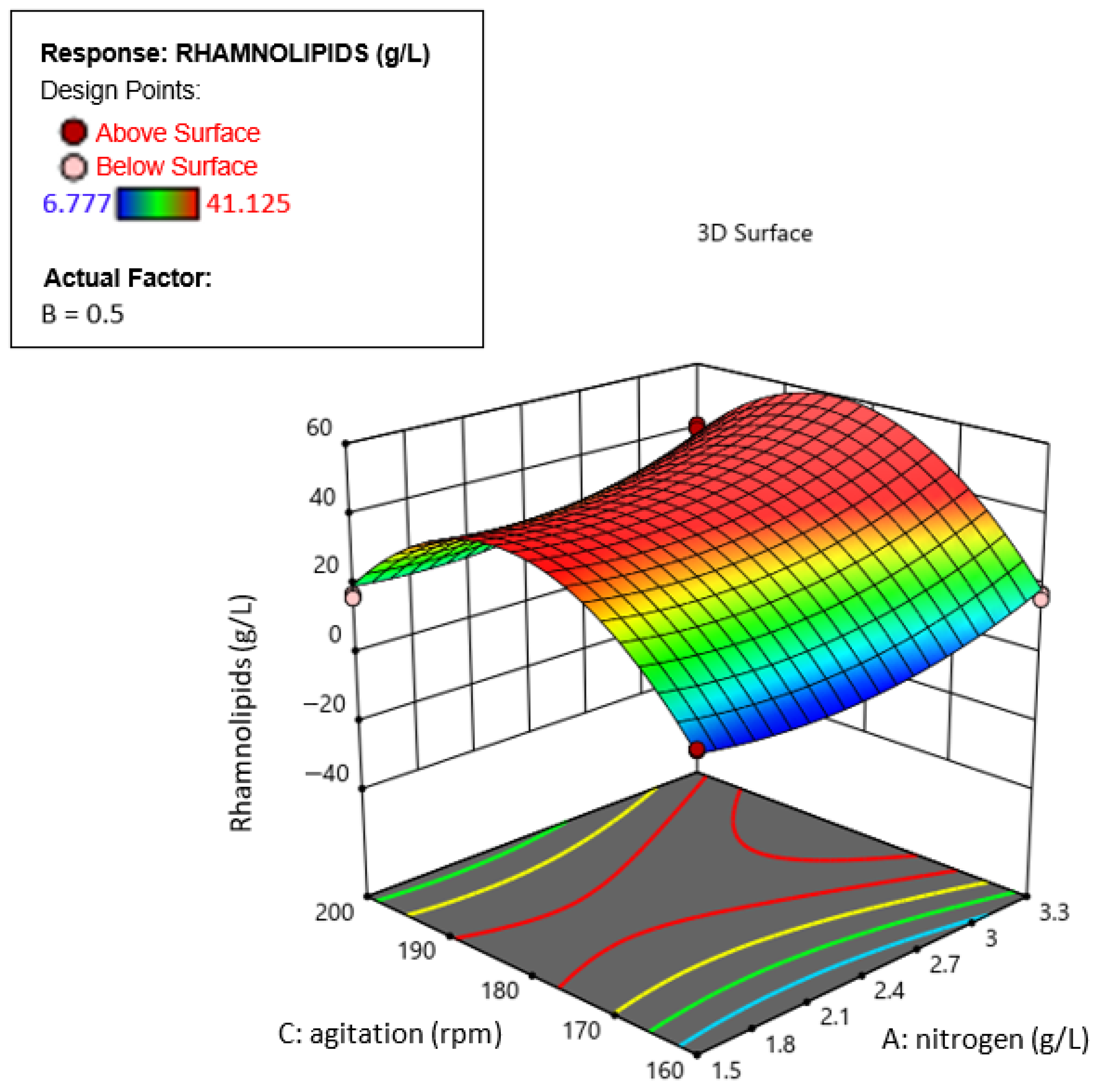

3.6. Response Surface Results

3.7. Optimization of Rhamnolipid (RL) Production

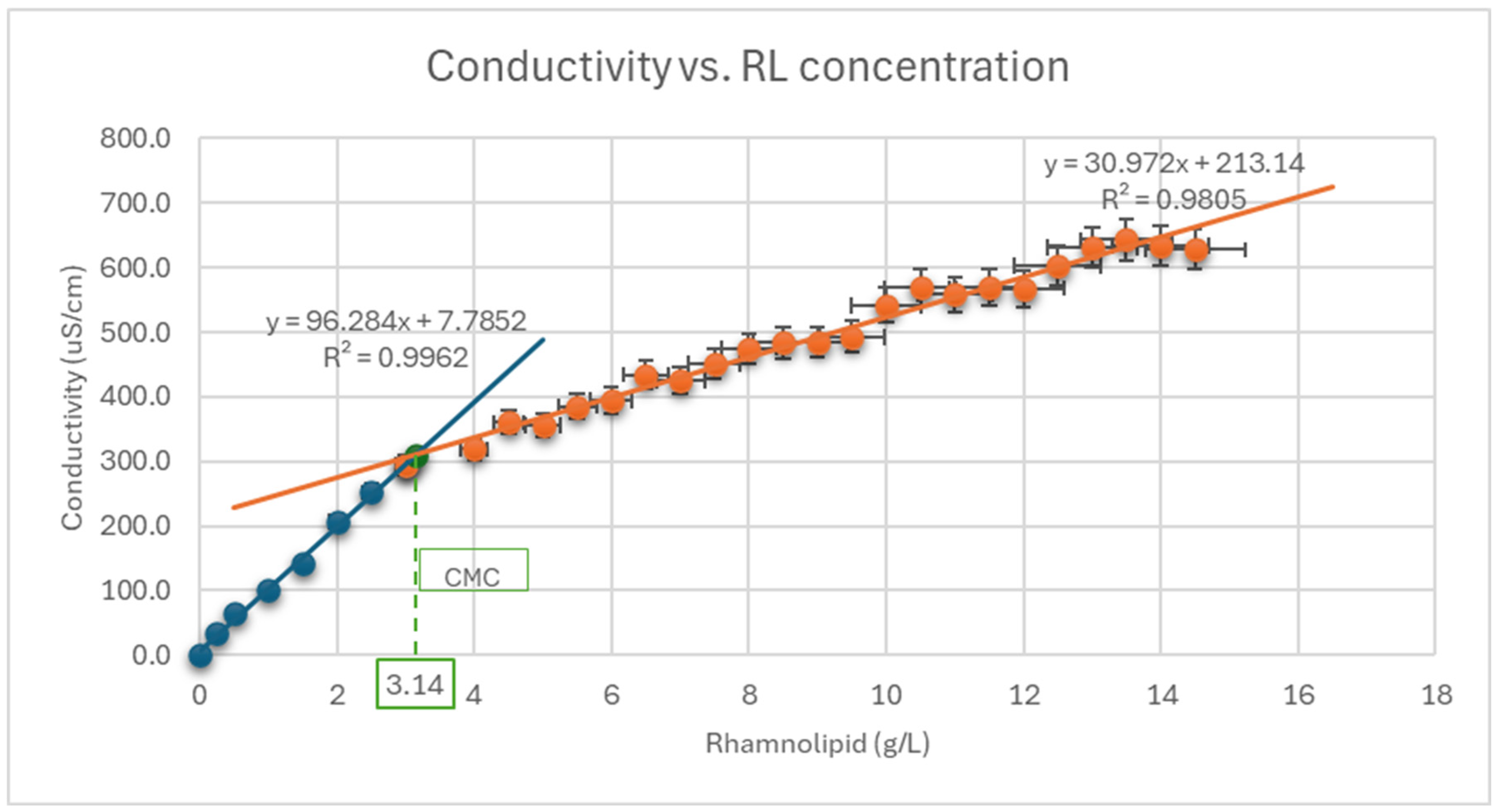

3.8. Critical Micelle Concentration

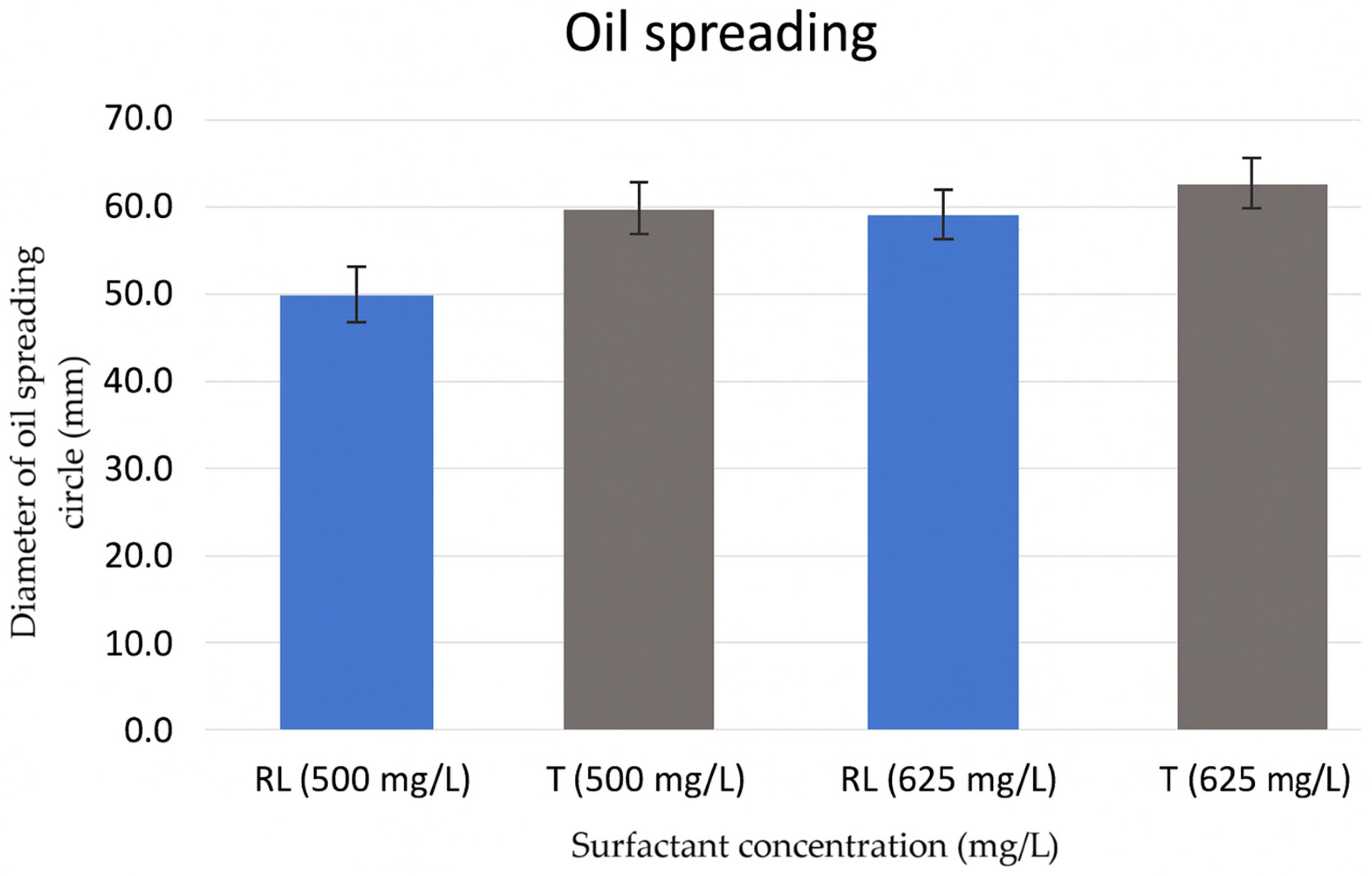

3.9. Oil Spreading Activity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CCD | Compound Central Design |

| CMC | Critical Micelle Concentration |

| RSM | Response Surface Methodology |

| DO | Dissolved Oxygen |

| RL | Rhamnolipid |

| SW | Siegmund and Wagner |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix A.2

| Nº | Factor A: Nitrogen Source (g/L) | Factor B: Aeration Rate (vvm) | Factor C: Agitation Speed (rpm) | Response: Rhamnolipids (g/L) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Theoretical | ||||

| 1 | 3.3 | 0.5 | 160 | 17.345 | 18.913 |

| 2 | 1.95 | 0.6 | 180 | 27.203 | 19.591 |

| 3 | 2.4 | 0.65 | 180 | 19.186 | 24.447 |

| 4 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 170 | 7.387 | 7.374 |

| 5 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 160 | 8.784 | 8.053 |

| 6 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 180 | 18.485 | 19.545 |

| 7 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 160 | 7.061 | 9.239 |

| 8 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 190 | 16.256 | 16.602 |

| 9 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 180 | 21.916 | 19.545 |

| 10 | 3.3 | 0.7 | 200 | 30.459 | 30.535 |

| 11 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 170 | 6.777 | 7.374 |

| 12 | 2.4 | 0.55 | 180 | 29.735 | 26.074 |

| 13 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 200 | 27.943 | 26.831 |

| 14 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 200 | 29.252 | 26.831 |

| 15 | 3.3 | 0.7 | 200 | 28.893 | 30.535 |

| 16 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 190 | 16.541 | 16.602 |

| 17 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 160 | 9.348 | 8.053 |

| 18 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 200 | 17.557 | 19.875 |

| 19 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 160 | 6.979 | 9.239 |

| 20 | 3.3 | 0.5 | 200 | 39.710 | 38.230 |

| 21 | 3.3 | 0.5 | 200 | 41.125 | 38.230 |

| 22 | 3.3 | 0.5 | 200 | 40.367 | 38.230 |

| 23 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 160 | 9.341 | 8.053 |

| 24 | 3.3 | 0.7 | 200 | 28.915 | 30.535 |

| 25 | 1.95 | 0.6 | 180 | 24.437 | 19.591 |

| 26 | 2.4 | 0.65 | 180 | 19.585 | 24.447 |

| 27 | 3.3 | 0.5 | 160 | 15.951 | 18.913 |

| 28 | 2.4 | 0.55 | 180 | 31.544 | 26.074 |

| 29 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 180 | 20.768 | 19.545 |

| 30 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 160 | 7.142 | 9.239 |

| 31 | 3.3 | 0.7 | 160 | 8.664 | 5.448 |

| 32 | 2.85 | 0.6 | 180 | 17.574 | 23.232 |

| 33 | 3.3 | 0.5 | 160 | 17.738 | 18.913 |

| 34 | 3.3 | 0.7 | 160 | 8.192 | 5.448 |

| 35 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 200 | 16.770 | 19.875 |

| 36 | 3.3 | 0.7 | 160 | 8.448 | 5.448 |

| 37 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 200 | 28.977 | 26.831 |

| 38 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 200 | 16.315 | 19.875 |

| 39 | 2.85 | 0.6 | 180 | 15.439 | 23.232 |

Appendix A.3

Appendix A.4

References

- Sarubbo, L.A.; Silva, M.d.G.C.; Durval, I.J.B.; Bezerra, K.G.O.; Ribeiro, B.G.; Silva, I.A.; Twigg, M.S.; Banat, I.M. Biosurfactants: Production, properties, applications, trends, and general perspectives. Biochem. Eng. J. 2022, 181, 108377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zeng, G.; Zhong, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, M.; Liu, G.; Yang, X.; Liu, S. Effect of rhamnolipid solubilization on hexadecane bioavailability: Enhancement or reduction? J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 322, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekhon-Randhawa, K.K.; Rahman, P.K. Rhamnolipid biosurfactants: Past, present, and future scenario of global market. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 106124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Z.; Peng, Y.; Wang, Q. Rhamnolipid production, characterization and fermentation scale-up by Pseudomonas aeruginosa with plant oils. Biotechnol. Lett. 2015, 37, 2033–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Armendáriz, B.; Cal-Y-Mayor-Luna, C.; El-Kassis, E.G.; Ortega-Martínez, L.D. Use of waste canola oil as a low-cost substrate for rhamnolipid production using Pseudomonas aeruginosa. AMB Express 2009, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.G.; Ballot, F.; Reid, S.J. Enhanced rhamnolipid production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa under phosphate limitation. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 26, 2179–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, H. Application of a Dynamic Method for the Volumetric Mass Transfer Coefficient Determination in the Scale-Up of Rhamnolipid Biosurfactant Production. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2018, 21, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paciello, L.; Parascandola, P. Determination of Volumetric Oxygen Transfer Coefficient to Evaluate the Maximum Performance of Lab Fermenters. CET J.—Chem. Eng. Trans. 2020, 79, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Bazsefidpar, S.; Mokhtarani, B.; Panahi, R.; Hajfarajollah, H. Overproduction of rhamnolipid by fed-batch cultivation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a lab-scale fermenter under tight DO control. Biodegradation 2019, 30, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Yang, X.; Xue, C.; Chen, Y.; Qu, L.; Lu, W. Enhanced rhamnolipids production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa based on a pH stage-controlled fed-batch fermentation process. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 117, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, D.G. Optimization of the Carbon Source for the Production of a Rhamnolipid Surfactant by a Native Strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa 6K11. Master’s Thesis, National University of San Marcos, Lima, Peru, 2015. Available online: https://cybertesis.unmsm.edu.pe/item/1c88b6ba-66e4-42d5-aeaa-869dcb8d5262f230 (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Guzmán, J.A. Optimization of Fermentation Parameters for the Production of Rhamnolipids by Pseudomonas aeruginosa 6K-11 in Submerged Cultures at Laboratory Scale. Master’s Thesis, National University of San Marcos, Lima, Peru, 2016. Available online: https://cybertesis.unmsm.edu.pe/item/0900ab87-ffd1-41ee-aced-dd958d68a8e0 (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Calleja, G.M. Identification of Rhamnolipids Produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa 6k-11 Contained in Halos Revealed on CTAB/MB Agar Using UPLC–MS/MS. Master’s Thesis, National University of San Marcos, Lima, Peru, 2016. Available online: https://cybertesis.unmsm.edu.pe/item/3a388105-2f79-4a60-82d0-07bf62c4f230 (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Tabuchi, T.; Martínez, D.; Hospinal, M.; Merino, F.; Gutiérrez, S. Optimización y modificación del método para la detección de ramnolípidos. Revista Peruana de Biología 2015, 22, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalde, M.A.; Merino-Rafael, F.A.; Gutiérrez-Moreno, S.M. Optimization of mineral nutrients to improve rhamnolipid production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa 6K-11. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2024, 99, 2170–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wang, L.; Nie, H.; Diwu, Z.; Nie, M.; Zhang, B. Optimization and characterization of rhamnolipid production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa NY3 using waste frying oil as the sole carbon. Biotechnol. Prog. 2021, 37, e3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, D. Rhamnolipid production from waste cooking oil using newly isolated halotolerant Pseudomonas aeruginosa M4. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsigny, M.; Petit, C.; Roche, A.-C. Colorimetric determination of neutral sugars by a resorcinol sulfuric acid micromethod. Anal. Biochem. 1988, 175, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, H.; Mayr, T.; Hobisch, M.; Borisov, S.; Klimant, I.; Krühne, U.; Woodley, J.M. Measurement of oxygen transfer from air into organic solvents. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2016, 91, 832–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Ochoa, F.; Gomez, E. Oxygen Transfer Rate Determination: Chemical, Physical and Biological Methods. In Encyclopedia of Industrial Biotechnology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuker, J.; Steier, A.; Wittgens, A.; Rosenau, F.; Henkel, M.; Hausmann, R. Integrated foam fractionation for heterologous rhamnolipid production with recombinant Pseudomonas putida in a bioreactor. AMB Express 2016, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkhipov, V.P.; Arkhipov, R.V.; Petrova, E.V.; Filippov, A. Micellar and solubilizing properties of rhamnolipids. Magn. Reason. Chem 2023, 61, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Liang, X.; Ban, Y.; Han, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, F. Comparison of Methods to Quantify Rhamnolipid and Optimization of Oil Spreading Method. Tenside Surfactants Deterg. 2016, 53, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasband, W. ImageJ 1.41o; National Institutes of Health: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. Available online: https://imagej.net/ij/ (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Zhong, C.; Ma, W. Evolution and equilibrium of a green technological innovation system: Simulation of a tripartite game model. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathania, A.S.; Jana, A.K. Utilization of waste frying oil for rhamnolipid production by indigenous Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Improvement through co-substrate optimization. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur-Asshifa, M.N.; Zambry, N.S.; Salwa, M.S.; Yahya, A.R.M. The influence of agitation on oil substrate dispersion and oxygen transfer in Pseudomonas aeruginosa USM-AR2 fermentation producing rhamnolipid in a stirred tank bioreactor. 3 Biotech. 2017, 7, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahraman, H.; Erenler, S.O. Rhamnolipid production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa engineered with the Vitreoscilla hemoglobin gene. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2012, 48, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kronemberger, F.A.; Anna, L.M.M.S.; Fernandes, A.C.L.B.; de Menezes, R.R.; Borges, C.P.; Freire, D.M.G. Oxygen-controlled Biosurfactant Production in a Bench Scale Bioreactor. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2008, 147, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.; Hammerbacher, A.S.; Bastian, M.; Nieken, K.J.; Klockgether, J.; Merighi, M.; Lapouge, K.; Poschgan, C.; Kölle, J.; Acharya, K.R.; et al. Oxygen-dependent regulation of c-di- GMP synthesis by SadC controls alginate production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 3390–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Shi, R.; Ma, F.; Han, S.; Zhang, Y. Oxygen effects on rhamnolipids production by P. aeruginosa. Microb. Cell Factories 2018, 17, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanavil, B.; Perumalsamy, M.; Seshagiri Rao, A. Studies on the Effects of Bioprocess Parameters and Kinetics of Rhamnolipid Production by P. aeruginosa NITT 6L. Chem. Biochem. Eng. Q. 2014, 28, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chayabutra, C.; Wu, J.; Ju, L.-K. Rhamnolipid production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa under denitrification: Effects of limiting nutrients and carbon substrates. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2001, 72, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Liu, S.; Xu, L.; Zhou, J.; Xin, F.; Zhang, W.; Qian, X.; Li, M.; Dong, W.; Jiang, M. Enhanced rhamnolipids production using a novel bioreactor system based on integrated foam-control and repeated fed-batch fermentation strategy. Biotechnol Biofuels 2020, 13, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azemi, M.A.F.M.; Rashid, N.F.M.; Saidin, J.; Effendy, A.W.M.; Bhubalan, K. Application of Sweetwater as Potential Carbon Source for Rhamnolipid Production by Marine Pseudomonas aeruginosa UMTKB-5. Int. J. Biosci. Biochem. Bioinform. 2016, 6, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sodagari, M.; Ju, L. Addressing the critical challenge for rhamnolipid production: Discontinued synthesis in extended stationary phase. Process Biochem. 2020, 91, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatila, F.; Diallo, M.M.; Şahar, U.; Ozdemir, G.; Yalçın, H.T. The effect of carbon, nitrogen and iron ions on mono-rhamnolipid production and rhamnolipid synthesis gene expression by Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 15442. Arch. Microbiol. 2020, 202, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Jiang, J.; He, N.; Jin, M.; Ma, K.; Long, X. High-Performance Production of Biosurfactant Rhamnolipid with nitrogen Feeding. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2019, 22, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, A.; Qureshi, M.; Ali, N.; Ali, M.; Hameed, A. Enhanced Production of rhamnolipid by P. aeruginosa using Response Surface Methodology. Asian J. Chem. 2014, 26, 1044–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albasri, H.M.; Almohammadi, A.A.; Alhhazmi, A.; Bukhari, D.A.; Waznah, M.S.; Mawad, A.M.M. Production and characterization of rhamnolipid biosurfactant from thermophilic Geobacillus stearothermophilus bacterium isolated from Uhud mountain. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1358175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, J.O.; Velásquez, W.; Chacón, Z.; Ball, M. Evaluación de la capacidad de ramnolípidos crudos para la remoción y emulsificación de hidrocarburos en un sistema modelo. Sci. J. Exp. Fac. Sci. Univ. Zulia 2015, 23, 39–50. [Google Scholar]

| Rhamnolipid Yield (mg/L) | Experimental | Theoretical |

|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SE | 25.21 ± 2.54 | 24.32 2.28 |

| Source | p-Value Sequential | Lack of Fit | Adjusted R2 | Predicted R2 | Annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.6455 | 0.6038 | |

| 2FI | 0.0017 | <0.0001 | 0.7567 | 0.7545 | |

| Quadratic | 0.0002 | <0.0001 | 0.8619 | 0.8112 | Suggested |

| Cubic | <0.0001 | 0.0800 | 0.9905 | 0.9849 | Aliased |

| Parmeter | Sum of Squares | Df | Mean of Squares | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 3354.04 | 9 | 372.67 | 27.36 | <0.0001 |

| A-Nitrogen concentration | 331.42 | 1 | 331.42 | 24.33 | <0.0001 |

| B-Aeration rate | 66.19 | 1 | 66.19 | 4.86 | 0.0356 |

| C-Agitation | 2127.17 | 1 | 2127.17 | 156.18 | <0.0001 |

| AB | 321.96 | 1 | 321.96 | 23.64 | <0.0001 |

| AC | 84.27 | 1 | 84.27 | 6.19 | 0.0189 |

| BC | 49.93 | 1 | 49.93 | 3.67 | 0.0655 |

| A2 | 20.78 | 1 | 20.78 | 1.53 | 0.2267 |

| B2 | 194.97 | 1 | 194.97 | 14.31 | 0.0007 |

| C2 | 340.90 | 1 | 340.90 | 25.03 | <0.0001 |

| Residual | 394.98 | 29 | 13.62 | ||

| Lack of adjustment | 374.37 | 5 | 74.87 | 87.22 | <0.0001 |

| Pure Error | 20.60 | 24 | 0.8585 | ||

| Cor Total | 3749.01 | 38 |

| N° | Nitrogen Source (g/L) | Aeration Rate (vvm) | Agitation Speed (rpm) | RL (g/L) | Desirability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.041 | 0.503 | 180.491 | 51.577 | 1.000 |

| 2 | 3.207 | 0.507 | 176.336 | 50.497 | 1.000 |

| 3 | 3.128 | 0.509 | 179.788 | 50.340 | 1.000 |

| 4 | 3.257 | 0.508 | 175.549 | 50.319 | 1.000 |

| 5 | 3.145 | 0.502 | 191.396 | 49.942 | 1.000 |

| 6 | 2.892 | 0.502 | 181.571 | 49.826 | 1.000 |

| 7 | 3.257 | 0.511 | 190.314 | 49.512 | 1.000 |

| 8 | 3.246 | 0.518 | 180.104 | 49.053 | 1.000 |

| 9 | 2.806 | 0.501 | 183.690 | 48.871 | 1.000 |

| 10 | 3.135 | 0.511 | 187.927 | 48.866 | 1.000 |

| 11 | 3.047 | 0.502 | 175.741 | 48.781 | 1.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alarcon-Ancajima, I.; Merino, F.; Gutierrez-Moreno, S. Influence of Dissolved Oxygen on the Pseudomonas aeruginosa 6K-11 Rhamnolipid Production. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 5, 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040147

Alarcon-Ancajima I, Merino F, Gutierrez-Moreno S. Influence of Dissolved Oxygen on the Pseudomonas aeruginosa 6K-11 Rhamnolipid Production. Applied Microbiology. 2025; 5(4):147. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040147

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlarcon-Ancajima, Ingrid, Fernando Merino, and Susana Gutierrez-Moreno. 2025. "Influence of Dissolved Oxygen on the Pseudomonas aeruginosa 6K-11 Rhamnolipid Production" Applied Microbiology 5, no. 4: 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040147

APA StyleAlarcon-Ancajima, I., Merino, F., & Gutierrez-Moreno, S. (2025). Influence of Dissolved Oxygen on the Pseudomonas aeruginosa 6K-11 Rhamnolipid Production. Applied Microbiology, 5(4), 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040147