Synergistic Antimicrobial Effect of Agro-Industrial Peel Extracts and Saccharomyces cerevisiae Against Listeria monocytogenes in Fruit Juice Matrices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Plant Materials and Collection Sites

- C. sinensis—Caluma in Los Ríos province (1°37′57″ S; 79°15′25″ W);

- A. cepa—Riobamba in Chimborazo province (1°41′46″ S; 78°39′15″ W);

- T. cacao—Vinces in Los Ríos province (1°33′00″ S; 79°44′00″ W);

- S. betaceum—Pelileo in Tungurahua province (1°22′ S; 78°32′ W).

2.3. Drying and Storage

2.4. Extraction Procedure

2.4.1. Soxhlet Extraction

2.4.2. Extract Handling

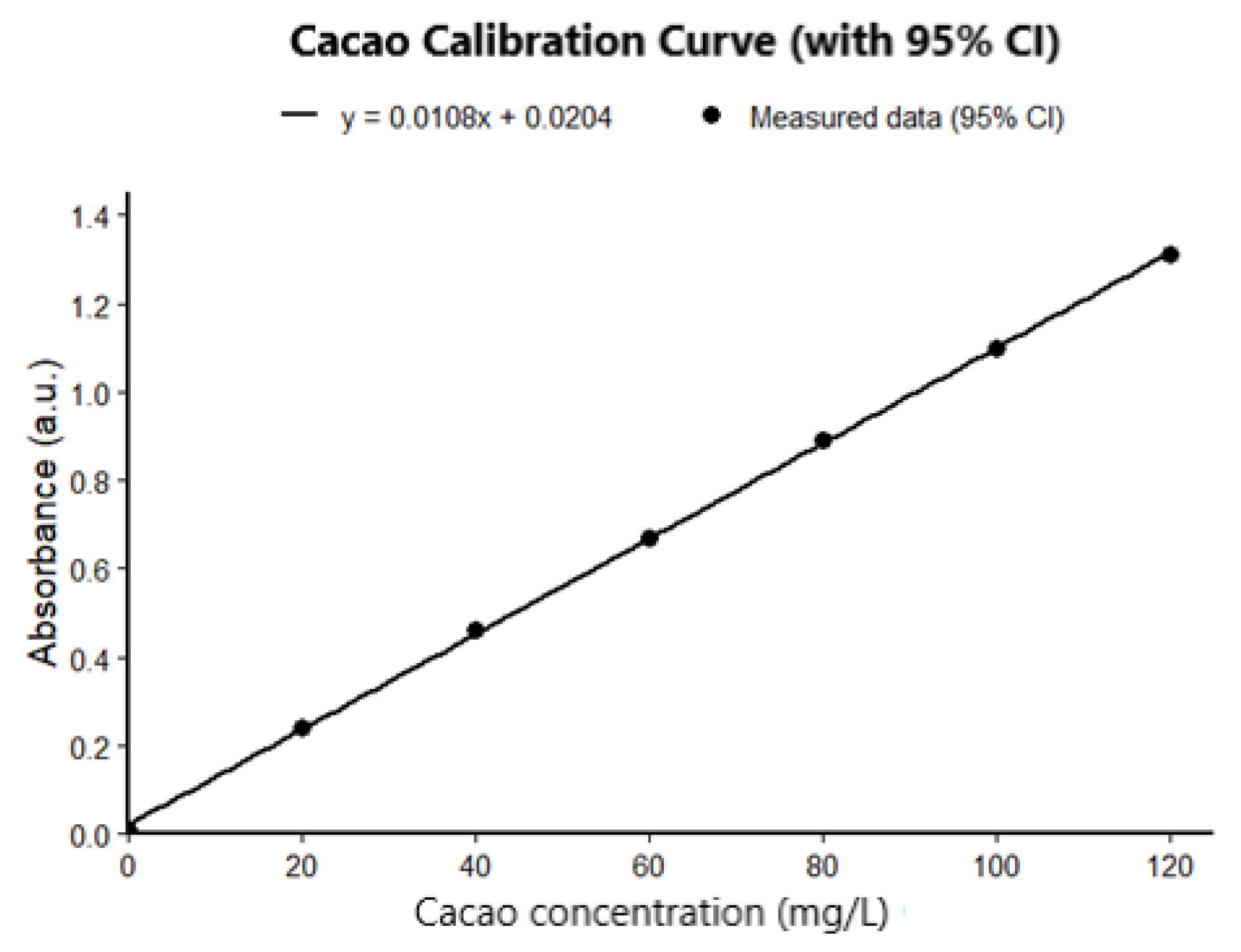

2.5. Determination of Total Polyphenol Content (TPC)

2.6. Microorganisms and Culture Conditions

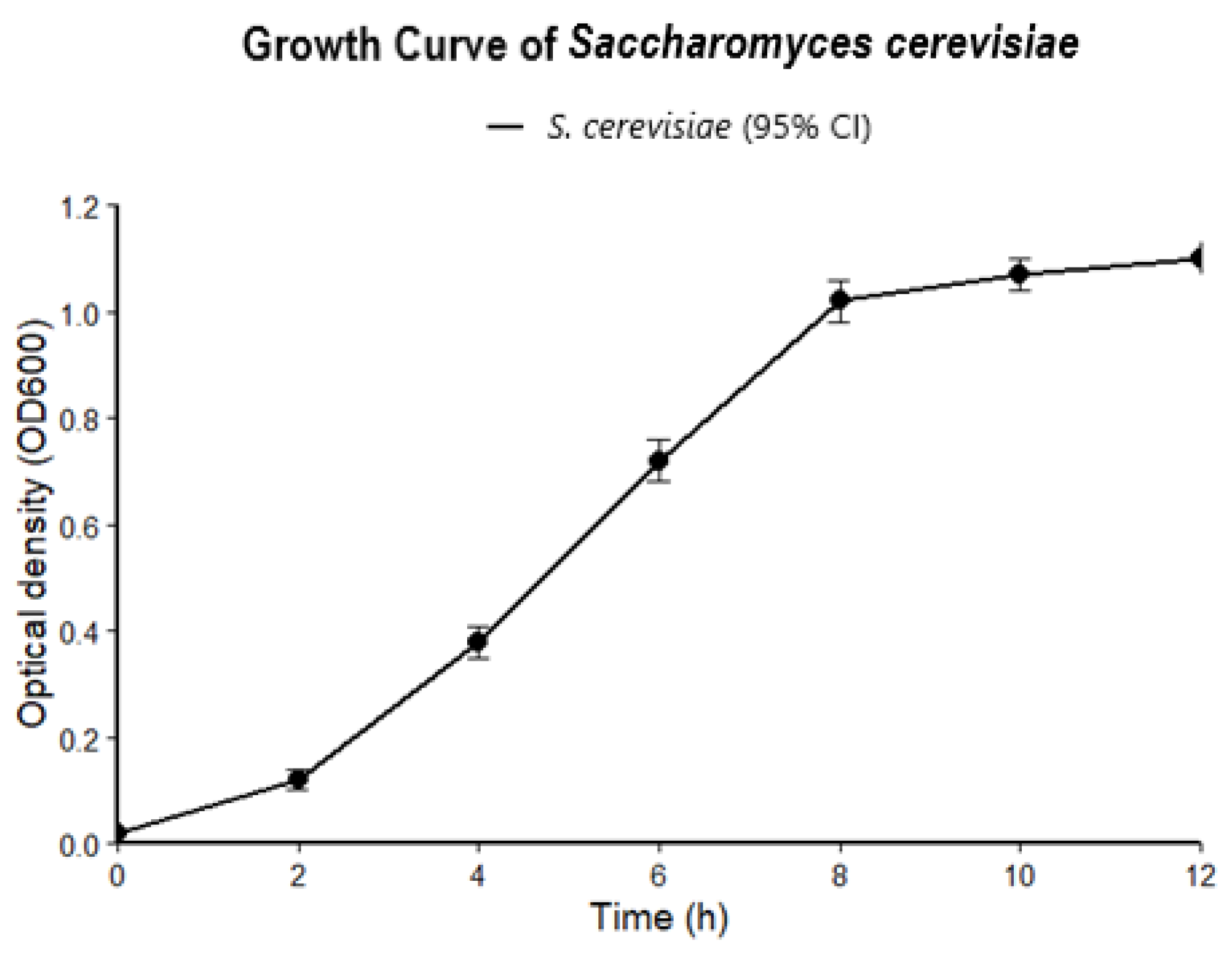

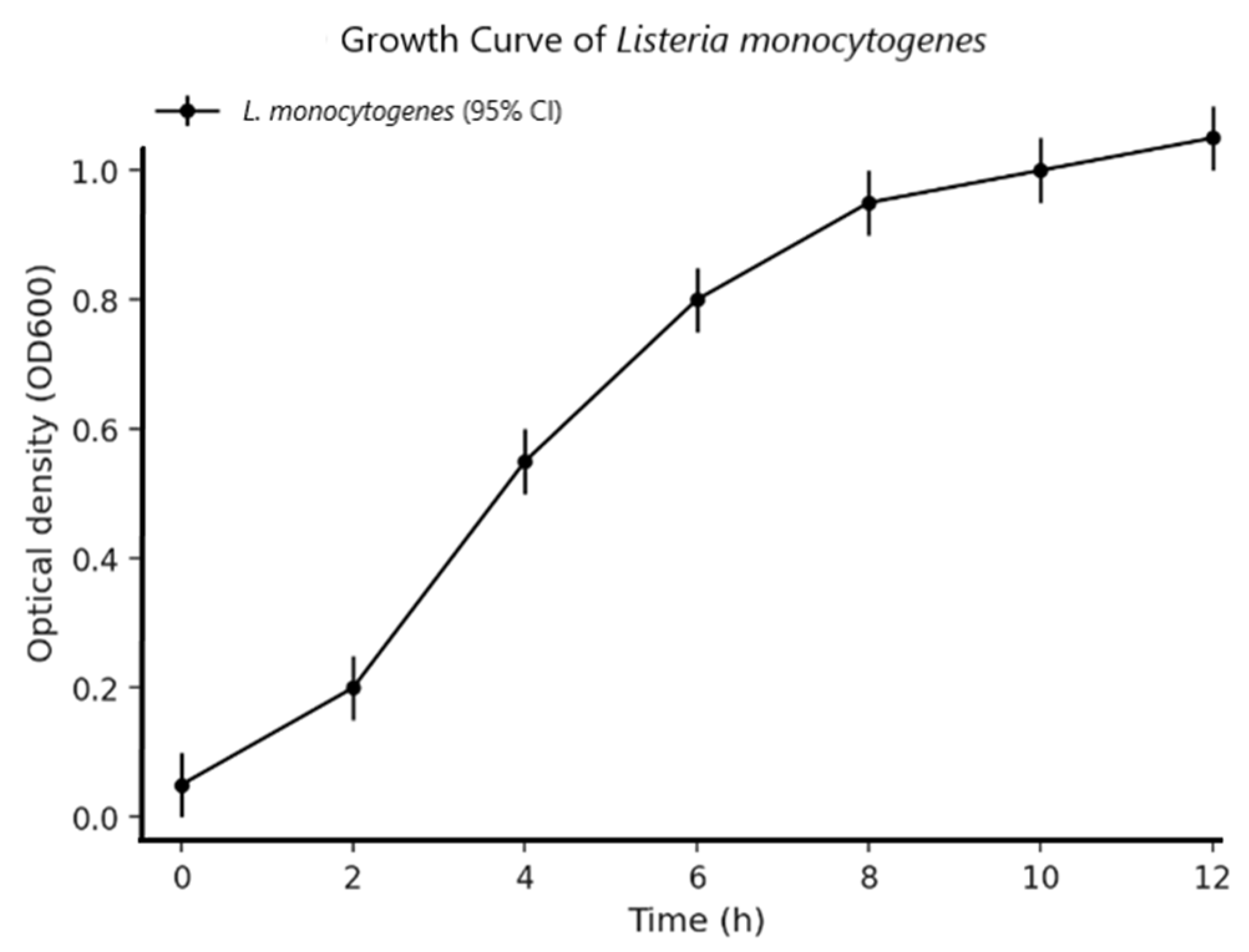

Isolation and Molecular Confirmation

2.7. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Assay

2.8. Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

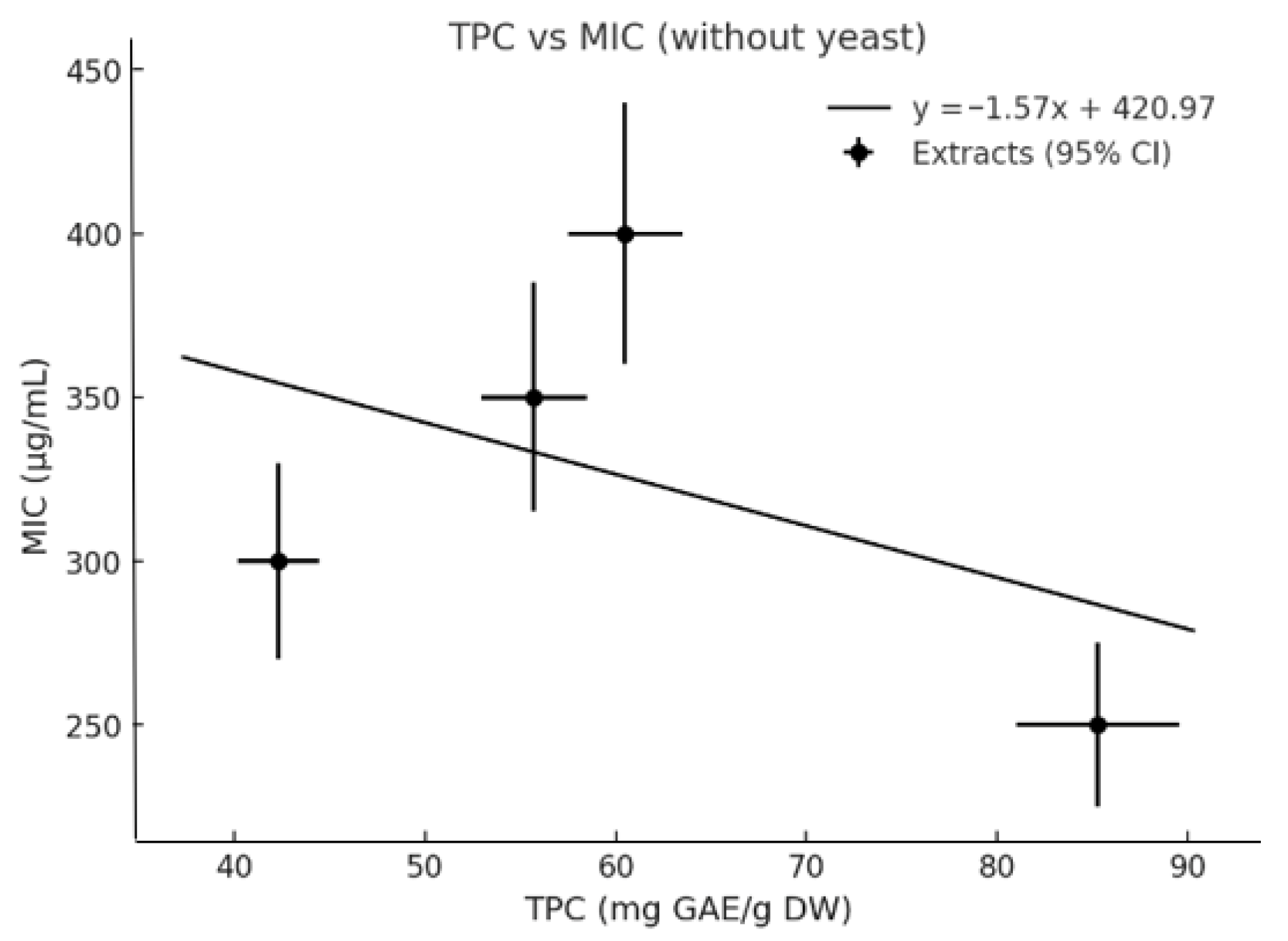

Correlation and Regression

3. Results

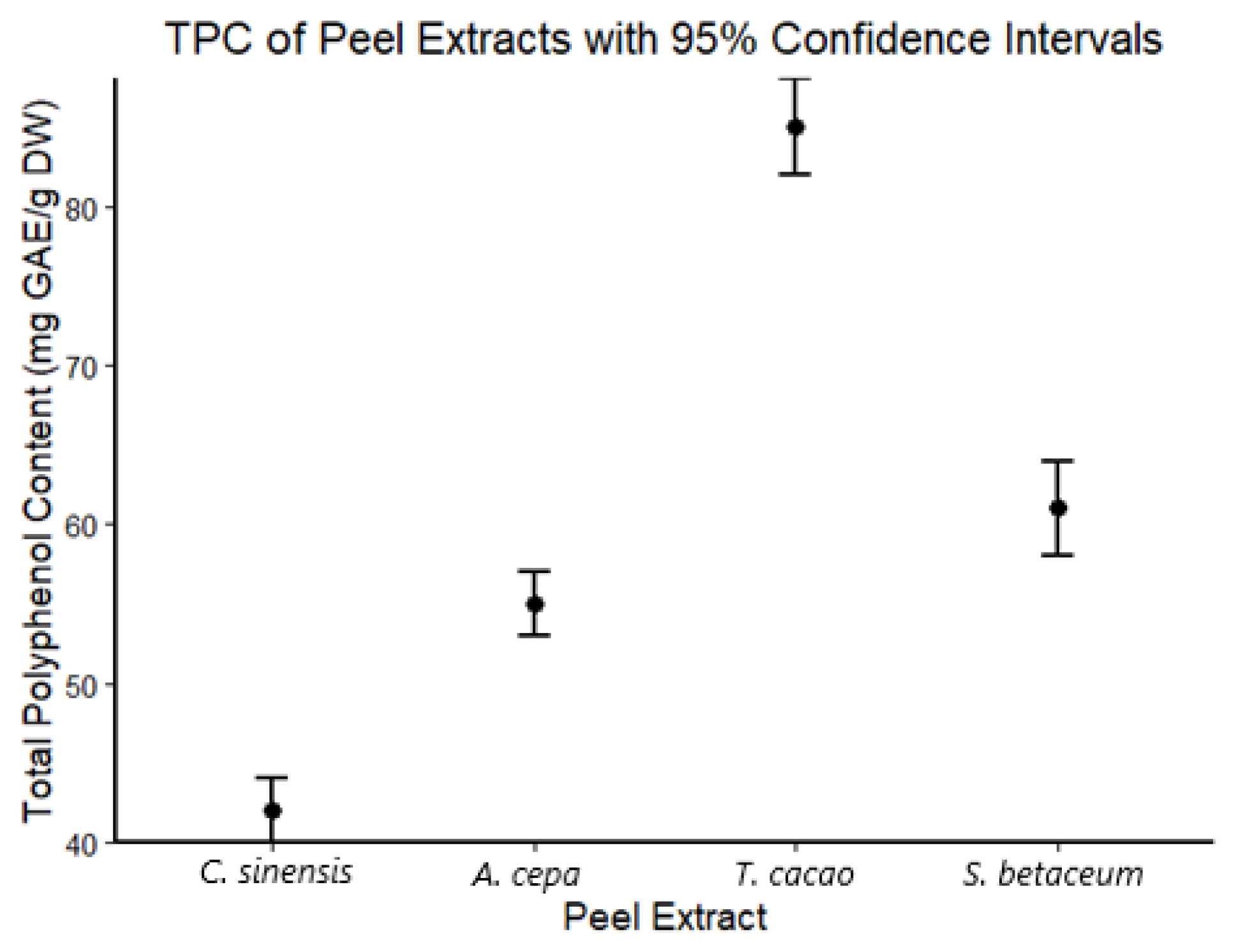

3.1. Extraction Yield and Total Polyphenol Content (TPC)

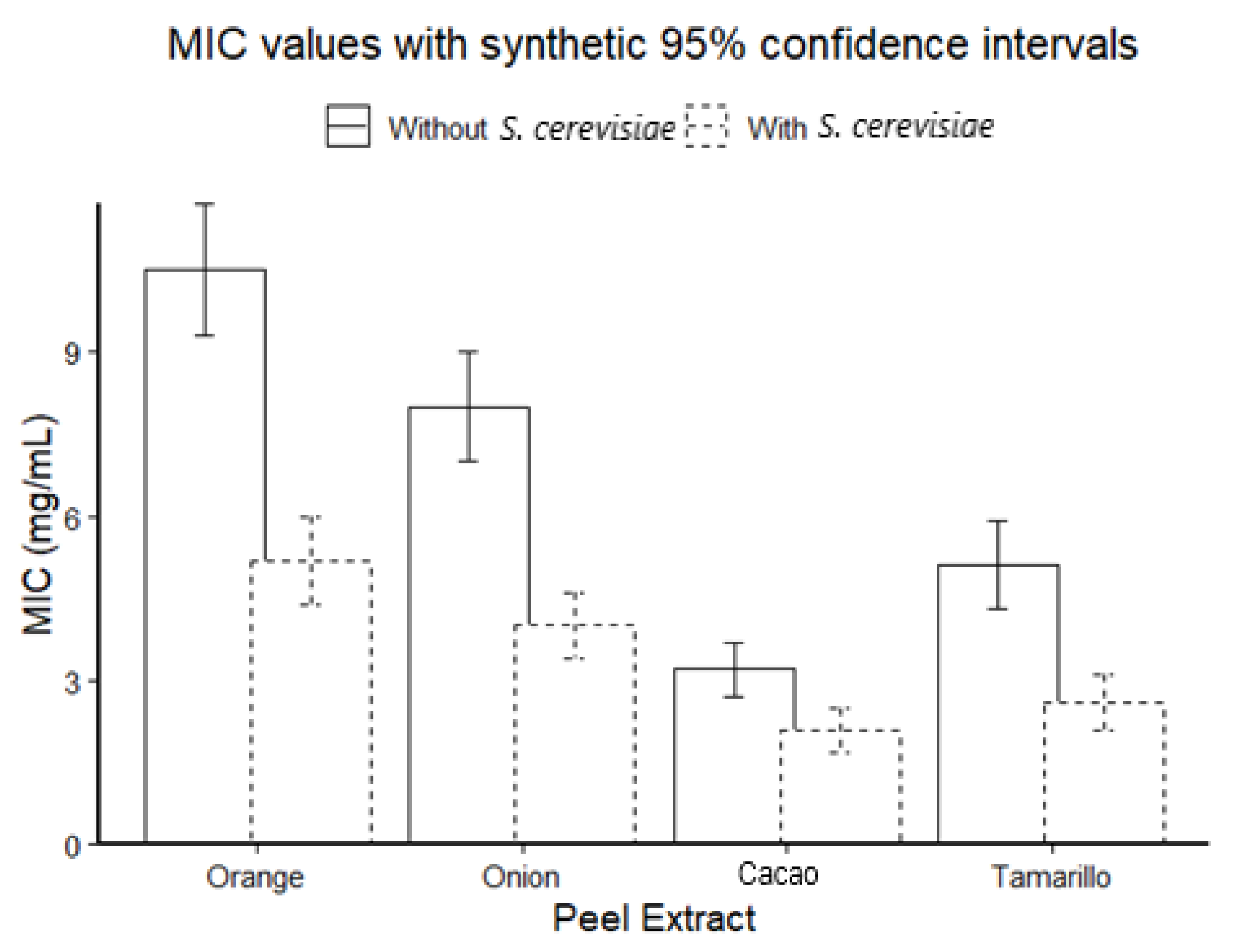

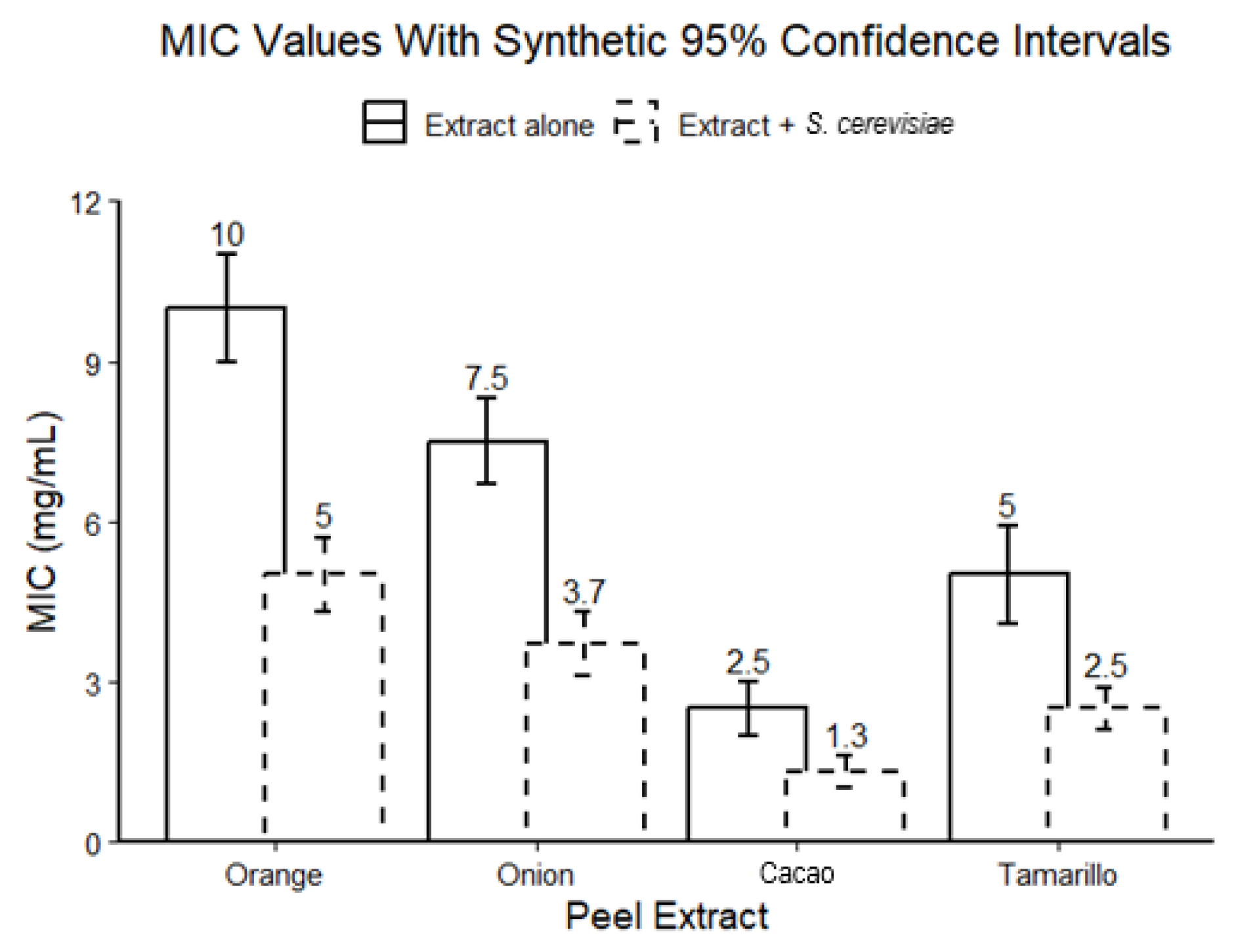

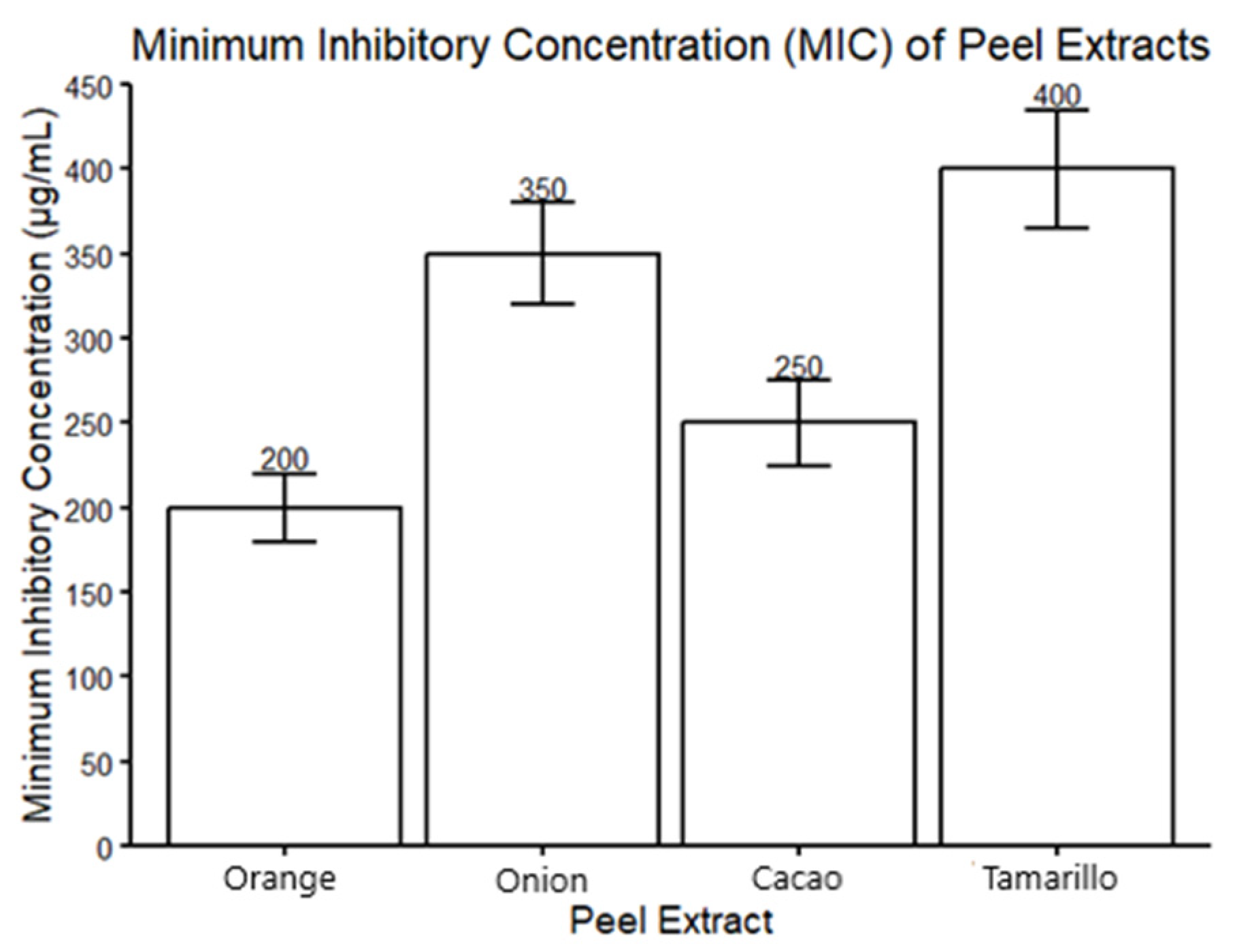

3.2. Antimicrobial Activity and Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

3.3. Interaction Effects and Statistical Relevance

3.4. Dehydration Process and Yield

3.5. Extraction Weights and Loss of Soluble Solids

3.5.1. Weighing of Samples and Centrifuge Tubes

3.5.2. Loss of Soluble Solids

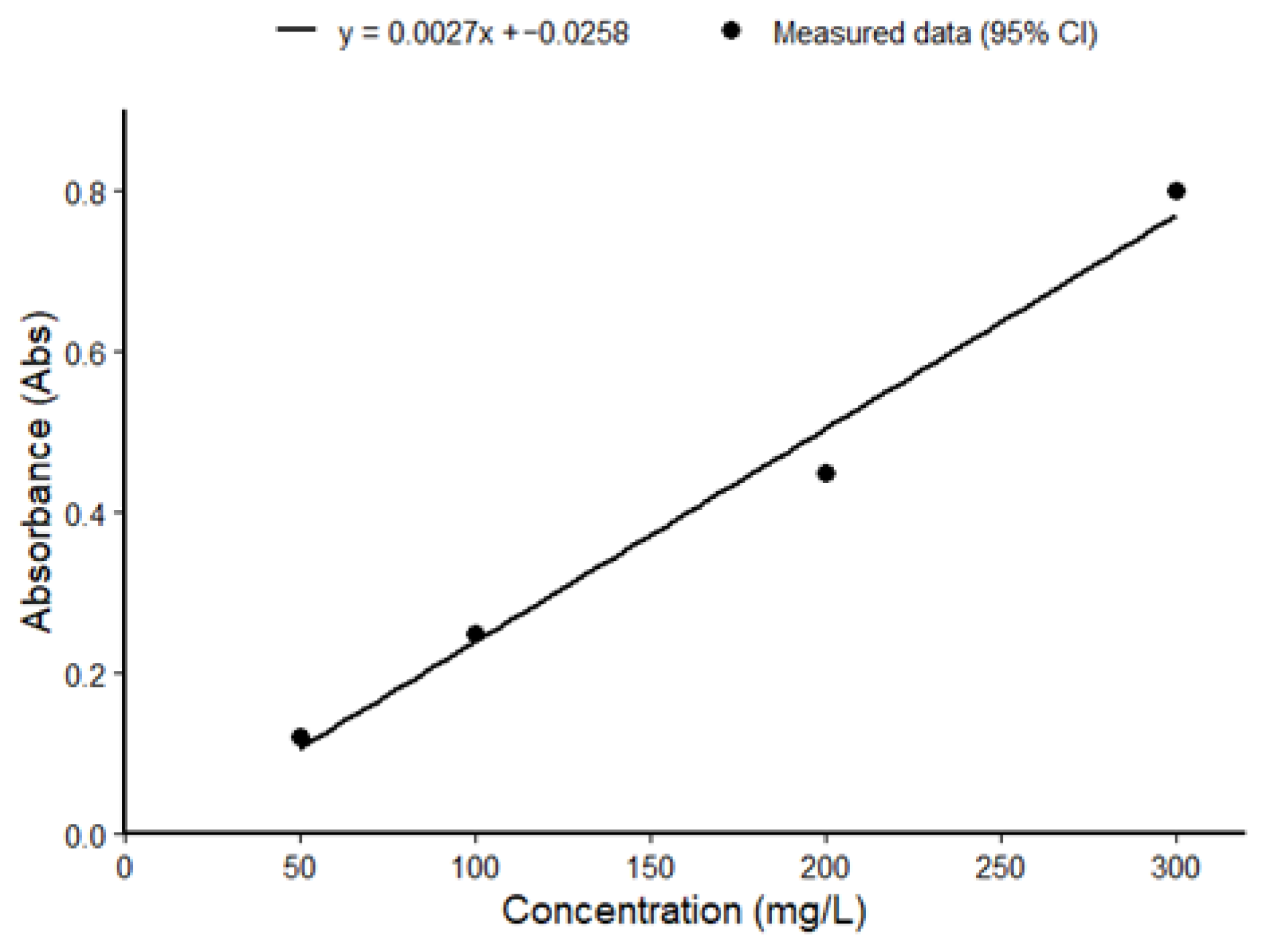

3.6. Quantification of TPC by UV Light Spectrophotometer

3.7. Quantification of Total Phenolic Content (TPC) Using the Folin–Ciocalteu Method

3.8. Relationship Between TPC and MIC

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanistic Insights and Synergy

- Membrane destabilization—Polyphenols integrate into lipid bilayers, while yeast metabolites increase permeability, promoting cytoplasmic leakage.

- Metabolic interference—Yeast-derived acids lower intracellular pH and ATP, amplifying the phenolic inhibition of key metabolic enzymes.

- ROS synergy—Both components elevate oxidative stress, polyphenols act as redox-cycling agents, and yeast metabolism produces ROS, overwhelming bacterial defenses.

4.2. Implications and Future Perspectives

- (1)

- Couple TPC data with LC-MS/MS fingerprinting to identify key phenolic subclasses (e.g., catechins, procyanidins, and quercetin derivatives);

- (2)

- Evaluate kinetic interactions between yeast and phenolics across pH and temperature ranges;

- (3)

- Quantify sensory and stability impacts at functional doses;

- (4)

- Validate the approach in real beverage systems using HACCP-aligned challenge tests.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reguengo, L.M.; Salgaço, M.K.; Sivieri, K.; Maróstica Júnior, M.R. Agro-industrial by-products: Valuable sources of bioactive compounds. Food Res. Int. 2022, 152, 110871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Fuente-Salcido, N.M.; Villarreal-Prieto, J.M.; Díaz León, M.A.; García Pérez, A.P. Evaluación de la actividad de los agentes antimicrobianos ante el desafío de la resistencia bacteriana. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Farm. 2015, 46, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Tirloni, E.; Centorotola, G.; Pomilio, F.; Torresi, M.; Bernardi, C.; Stella, S. Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat (RTE) delicatessen foods: Prevalence, genomic characterization of isolates and growth potential. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 400, 110515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.S.; D’Orazio, S.E.F. Listeria monocytogenes: Cultivation and laboratory maintenance. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 2013, 31, 9B.2.1–9B.2.7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, A.I.; Rodríguez, E.C. Distribución y caracterización fenotípica y genotípica de Listeria monocytogenes en aislamientos de alimentos, Colombia, 2010–2018. Biomédica 2021, 41, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiallos Maravilla, N. Obtención de Compuestos Polifenólicos con Actividad Antimicrobiana a Partir de Residuos Agroindustriales. Conference: VIII Congreso Internacional de Ingeniería Agroindustrial. 2022. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/364915542_Obtencion_de_compuestos_polifenolicos_con_actividad_antimicrobiana_a_partir_de_residuos_agroindustriales?channel=doi&linkId=635e5c6d96e83c26eb685348&showFulltext=true (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Hasan, M.; Hoque, M.M.; Hosen, M.B.; Akter, S.; Paul, A.K.; Rahman, M.M. Antimicrobial activity of peels and physicochemical properties of juice prepared from indigenous citrus fruits of Sylhet region, Bangladesh. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-López, N.J.; Enríquez-Valencia, S.A.; Zuñiga Martínez, B.S.; González-Aguilar, G.A. Residuos agroindustriales como fuente de nutrientes y compuestos fenólicos. Epistemus 2023, 17, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkadem, W.; Belguith, K.; Indio, V.; Oussaief, O.; Guluzade, G.; ElHatmi, H.; Serraino, A.; De Cesare, A.; Boudhrioua, N. Assessment of the Anti-Listeria Effect of Citrus limon Peel Extract In Silico, In Vitro, and in Fermented Cow Milk During Cold Storage. Foods 2025, 14, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joković, N.; Matejić, J.; Zvezdanović, J.; Stojanović-Radić, Z.; Stanković, N.; Mihajilov-Krstev, T.; Bernstein, N. Onion Peel as a Potential Source of Antioxidants and Antimicrobial Agents. Agronomy 2024, 14, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Barbhai, M.D.; Hasan, M.; Punia, S.; Dhumal, S.; Radha; Rais, N.; Chandran, D.; Pandiselvam, R.; Kothakota, A.; et al. Onion (Allium cepa L.) peels: A review on bioactive compounds and biomedical activities. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 141, 112498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, N.A.; Pareek, S. Antimicrobial assessment of polyphenolic extracts from onion skin. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 433. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Yanamango, E.; Obregon, D.; Ibañez, A. A comprehensive review of the development of green extraction methods and encapsulation of theobromine from cocoa bean shells for nutraceutical applications. Food Eng. Rev. 2025, 17, 1083–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diep, T.; Pook, C.; Yoo, M. Phenolic and Anthocyanin Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Tamarillo (Solanum betaceum Cav.). Antioxidants 2020, 9, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, A.M.R.; Teodoro, A.J.; Mariutti, L.R.B.; Fonseca, J.C.N.D. Tamarillo (Solanum betaceum) wastes and by-products: Composition and bioactivity. Heliyon 2024, 10, e316316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papillo, V.A.; Locatelli, M.; Travaglia, F.; Bordiga, M.; Garino, C.; Coïsson, J.D.; Arlorio, M. Cocoa hulls polyphenols stabilized by microencapsulation as functional ingredient for bakery applications. Food Res. Int. 2019, 115, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abutayeh, R.F.; Ayyash, M.A.K.; Alwany, R.A.; Abuodeh, A.; Jaber, K.; Al-Najjar, M.A.A. Exploring the antimicrobial potential of pomegranate peel extracts (PPEs): Extraction techniques and bacterial susceptibility. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0315173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liao, C.; Ouyang, X.; Kahramanoğlu, I.; Gan, Y.; Li, M. Antimicrobial Activity of Pomegranate Peel and Its Applications on Food Preservation. J. Food Qual. 2020, 2020, 8850339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapadia, S.P.; Pudakalkatti, P.S.; Shivanaikar, S. Detection of antimicrobial activity of banana peel (Musa paradisiaca L.) on Porphyromonas gingivalis and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans: An in vitro study. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2015, 7, S32–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semangoen, T.; Chotigawin, R.; Sangnim, T.; Chailerd, N.; Pahasup-anan, T.; Huanbutta, K. Evaluation of banana peel extract as an antimicrobial agent in livestock farming. Sustain. Agric. Environ. 2024, 3, e12118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kučuk, N.; Primožič, M.; Kotnik, P.; Knez, Ž.; Leitgeb, M. Mango peels as an industrial by-product: A sustainable source of compounds with antioxidant and antimicrobial activity. Foods 2024, 13, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangsiri, S.; Suttisansanee, U.; Koirala, P.; Chathiran, W.; Srichamnong, W.; Li, L.; Nirmal, N. Phenolic content of Thai Bao mango peel and its in-vitro antimicrobial activity. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 31, 103015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-Martínez, F.J.; Barrajón-Catalán, E.; Herranz-López, M.; Micol, V. Antibacterial plant compounds, extracts and essential oils: An updated review on their effects and putative mechanisms of action. Phytomedicine 2021, 90, 153626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, P.D.C.; Hashim, N.; Basri, M.S.; Saari, N.B.; Aji Muhammad, D.R. Unlocking the potential of cacao bean shell as a functional food additive: Composition, applications, optimization, and future directions—A review. Food Chem. 2025, 492, 145471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejía-Barajas, J.A.; Montoya-Pérez, R.; Cortés-Rojo, C.; Saavedra-Molina, A. Levaduras termotolerantes: Aplicaciones industriales. estrés oxidativo y respuesta antioxidante. Inf. Tecnol. 2016, 27, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freimoser, F.M.; Rueda-Mejía, M.P.; Tilocca, B.; Migheli, Q. Biocontrol yeasts: Mechanisms and applications. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 35, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wu, M.; Qin, X.; Dong, Q.; Li, Z. Antimicrobial function of yeast against pathogenic and spoilage microorganisms via either antagonism or encapsulation: A review. Food Microbiol. 2023, 110, 104242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Wang, H.; Lin, Y.; Feng, S.; Li, X. Biocontrol mechanisms of antagonistic yeasts on postharvest fruits and vegetables and the approaches to enhance the biocontrol potential of antagonistic yeasts. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2025, 430, 111038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azghar, A.; Dalli, M.; Azizi, S.; Benaissa, E.M.; Ben Lahlou, Y.; Elouennass, M.; Maleb, A. Chemical Composition and Antibacterial Activity of Citrus Peels Essential Oils Against Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria: A Comparative Study. J. Herb. Med. 2023, 42, 100799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaideh, S.; Olaimat, A.N.; Al-Holy, M.; Al-Nabulsi, A.; Al-Qadiri, H.; Hamed, S.; Al-Awwad, N.; Khataybeh, B.; Ababneh, A.; Elsahoryi, N.; et al. The antimicrobial activity of pomegranate peel extract incorporated in edible chitosan and gelatin coatings against Salmonella enterica on Medjool dates. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2025, 37, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.; Silva, V.; Dapkevicius, M.L.N.E.; Igrejas, G.; Barros, L.; Heleno, S.A.; Reis, F.S.; Poeta, P. From Apple Waste to Antimicrobial Solutions: A Review of Bioactive Compounds and Applications. Molecules 2025, 30, 3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Cadavid, E.; Ramírez-Castrillón, M.; López-Arboleda, A.; Mambuscay, L. Estandarización de un Protocolo Sencillo para la Extracción de ADN Genómico de Levaduras. 2009. Available online: https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/handle/unal/24639 (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Ramos, R.T.M.; Bezerra, I.C.F.; Ferreira, M.R.A.; Soares, L.A.L. Spectrophotometric quantification of polyphenols in herbal material, crude extract, and fractions from leaves of Eugenia uniflora Linn. Pharmacogn. Res. 2017, 9, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chico, M.F. Valorization of cocoa by products: Applications and perspectives in the food industry. Aliment. Cienc Ing. 2022, 29, 57–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, J.; González, G.; Fuentes, G. Evaluación de la Actividad Antioxidante de Extractos Obtenidos a Partir de la Cáscara de Naranja Valencia (Citrus sinensis L.). 2015, p. 28. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305440769_Evaluacion_de_la_actividad_antioxidante_de_extractos_obtenidos_a_partir_de_la_cascara_de_naranja_valencia_Citrus_sinensis_L (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Tam, C.C.; Nguyen, K.; Nguyen, D.; Hamada, S.; Kwon, O.; Kuang, I.; Gong, S.; Escobar, S.; Liu, M.; Kim, J.; et al. Antimicrobial properties of tomato leaves, stems, and fruit and their relationship to chemical composition. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2021, 21, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Martínez, F.J.; Barrajón-Catalán, E.; Encinar, J.A.; Rodríguez-Díaz, J.C.; Micol, V. Antimicrobial Capacity of Plant Polyphenols against Gram-positive Bacteria: A Comprehensive Review. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 27, 2576–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rossi, L. Antimicrobial potential of polyphenols: Mechanisms and applications. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A.B.B.; Fuertes, M.M.P.; Ramírez, G.E.M. Uso potencial de residuos agroindustriales como fuente de compuestos fenólicos con actividad biológica. MediSur 2023, 21, 1322–1330. [Google Scholar]

| Peel (By-Product) | Dominant/Active Phenolics (Examples) | Representative Antimicrobial Targets | Typical Activity Reported | Notes/Applications | Key Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citrus (lemon/orange) | Flavanones (hesperidin and naringin), phenolics; terpenes (limonene) | Listeria monocytogenes, S. aureus, and E. coli | Growth-rate reduction and ~2-log reductions in fermented dairy; MICs strain/matrix-dependent. | Effective in cold storage; aroma compounds may aid hurdle tech. | [7,9] |

| Onion peel | Quercetin and quercetin-3-glucoside/rutinoside | Gram ± incl. S. aureus and E. coli | Solvent-dependent inhibition; sonication/UAEx improve yields. | High TPC; robust literature for food use. | [10,11,12] |

| Pomegranate peel | Punicalagin, ellagic acid, and gallic acid (tannins) | Broad spectrum incl. Salmonella, E. coli, and Listeria | Frequent strong inhibition; low mg/mL MICs in vitro | Stable powders; color may impact sensory attributes. | [17,18,30] |

| Banana peel | Catechins, tannins, and carotenoids | Oral and foodborne pathogens | Clear inhibition zones; livestock and food interest | Abundant waste stream | [19,20] |

| Mango peel | Mangiferin, quercetin, and phenolic acids | Gram ± spoilage flora | High TPC; consistent antioxidant/antimicrobial signals | Industrial by-product with scale | [18,21] |

| Apple peel/pomace | Phloridzin, phloretin, chlorogenic acid | S. aureus, skin & food bacteria | Notable activity vs. Gram+; emerging MIC data | Natural preservative candidate | [31] |

| Cacao bean shell (hull) | Catechin, epicatechin, and procyanidins | Foodborne and spoilage bacteria (var.) | Bioactivity retained via microencapsulation | Major by-product; stability is key | [13,16] |

| Tamarillo peel | Ellagic acid, rutin, catechin, and anthocyanins | Gram ± (var.; emerging) | Well-characterized phenolics; antimicrobial reports increasing | Relevant to fruit beverages | [14] |

| C. sinensis (A) | A. cepa (B) | T. cacao (C) |

|---|---|---|

| A1E1 (200 µg/mL) | B1E1 (200 µg/mL) | C1E1 (200 µg/mL) |

| A2E1 (300 µg/mL) | B2E1 (300 µg/mL) | C2E1 (300 µg/mL) |

| A3E1 (400 µg/mL) | B3E1 (400 µg/mL) | C3E1 (400 µg/mL) |

| Extract | Concentration (µg/mL) | Replica 1 | Replica 2 | Replica 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. sinensis | 200 | E1 | E2 | E3 |

| C. sinensis | 300 | E4 | E5 | E6 |

| C. sinensis | 400 | E7 | E8 | E9 |

| A. cepa | 200 | E10 | E11 | E12 |

| A. cepa | 300 | E13 | E14 | E15 |

| A. cepa | 400 | E16 | E17 | E18 |

| T. cacao | 200 | E19 | E20 | E21 |

| T. cacao | 300 | E22 | E23 | E24 |

| T. cacao | 400 | E25 | E26 | E27 |

| S. betaceum | 200 | E28 | E29 | E30 |

| S. betaceum | 300 | E31 | E32 | E33 |

| S. betaceum | 400 | E34 | E35 | E36 |

| Extract Type | Concentration (µg mL−1) | Treatment Code | Yeast Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. sinensis (A) | 200 | A1E1 | 3 units mL−1 H2O |

| 300 | A2E1 | 3 units mL−1 H2O | |

| 400 | A3E1 | 3 units mL−1 H2O | |

| A. cepa (B) | 200 | B1E1 | 3 units mL−1 H2O |

| 300 | B2E1 | 3 units mL−1 H2O | |

| 400 | B3E1 | 3 units mL−1 H2O | |

| T. cacao (C) | 200 | C1E1 | 3 units mL−1 H2O |

| 300 | C2E1 | 3 units mL−1 H2O | |

| 400 | C3E1 | 3 units mL−1 H2O | |

| S. betaceum (D) | 200 | D1E1 | 3 units mL−1 H2O |

| 300 | D2E1 | 3 units mL−1 H2O | |

| 400 | D3E1 | 3 units mL−1 H2O |

| Extract Type | Concentration (µg mL−1) | Yeast Inoculum (Units mL−1 H2O) | Replica 1 | Replica 2 | Replica 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. sinensis (A) | 200 | 3 | E1 | E2 | E3 |

| C. sinensis (A) | 300 | 3 | E4 | E5 | E6 |

| C. sinensis (A) | 400 | 3 | E7 | E8 | E9 |

| A. cepa (B) | 200 | 3 | E10 | E11 | E12 |

| A. cepa (B) | 300 | 3 | E13 | E14 | E15 |

| A. cepa (B) | 400 | 3 | E16 | E17 | E18 |

| T. cacao (C) | 200 | 3 | E19 | E20 | E21 |

| T. cacao (C) | 300 | 3 | E22 | E23 | E24 |

| T. cacao (C) | 400 | 3 | E25 | E26 | E27 |

| S. betaceum (D) | 200 | 3 | E28 | E29 | E30 |

| S. betaceum (D) | 300 | 3 | E31 | E32 | E33 |

| S. betaceum (D) | 400 | 3 | E34 | E35 | E36 |

| Extract | TPC (mg GAE/g DW) |

|---|---|

| C. sinensis | 42.3 ± 1.2 d |

| A. cepa | 55.7 ± 1.5 b |

| T. cacao | 85.3 ± 2.1 a |

| S. betaceum | 60.5 ± 1.8 c |

| Plant Material | Initial Weight | Final Weight | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T. cacao | 320.40 g | 110.10 g | 34 |

| A. cepa | 138.10 g | 18.63 g | 13 |

| C. sinensis | 280.74 g | 89.96 g | 32 |

| S. betaceum | 728.55 g | 104.10 g | 14 |

| Sample | Grinding Balls by Weight (g) | Weight of Centrifuge Tubes (g) |

|---|---|---|

| T. cacao | m1: 115.3200 m2: 123.4500 m3: 121.7890 | t1: 10.5000 t2: 10.6000 t3: 10.4500 |

| A. cepa | m1: 109.0225 m2: 97.5165 m3: 132.4163 | t1:10.1162 t2: 9.9466 t3: 9.9649 |

| C. sinensis | m1: 169.7243 m2:168.1958 m3: 180.4852 | t1:10.7882 t2:10.1897 t3: 10.2107 |

| S. betaceum | m1: 109.0127 m2: 97.5113 m3: 132.4039 | t1: 9.7225 t2: 9.6373 t3: 10.0843 |

| Sample | Weight of Centrifuge Tubes (Vacuum; g) | Weight of Lyophilized Centrifuge Tubes (g) | Total Extract (g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T. cacao | t1: 10.2000 t2: 10.3000 t3: 10.1500 | T1L: 12.5000 T2L: 12.6000 T3L: 12.5500 | Ext 1: 2.3000 Ext 2: 2.4000 Ext 3: 2.3500 |

| A. cepa | t1: 10.1162 t2: 9.9466 t3: 9.9649 | T1L: 12.8867 T2L: 12.7436 T3L: 12.7429 | Ext 1: 2.7705 Ext 2: 2.7970 Ext 3: 2.7780 |

| C. sinensis | t1: 10.7882 t2: 10.1897 t3: 10.2107 | T1L: 12.4329 T2L: 12.3501 T3L: 11.9363 | Ext 1: 2.2547 Ext 2: 2.1604 Ext 3: 1.7256 |

| S. betaceum | t1: 9.7225 t2: 9.6373 t3: 10.0843 | T1L: 12.7195 T2L: 12.7456 T3L: 13.1384 | Ext 1: 2.9970 Ext 2: 3.1083 Ext 3: 3.0541 |

| Sample | Weight of Centrifuge Tubes (Vacuum; g) | Weight of Lyophilized Centrifuge Tubes (g) | Soluble Solids Loss (g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T. cacao | t1: 10.2000 t2: 10.3000 t3: 10.1500 | T1L: 12.5000 T2L: 12.6000 T3L: 12.5500 | Ps 1: 2.3000 Ps 2: 2.4000 Ps 3: 2.3500 |

| A. cepa | t1: 10.1162 t2: 9.9466 t3: 9.9649 | T1L: 12.8867 T2L: 12.7436 T3L: 12.7429 | Ps 1: 3.2295 Ps 2: 3.203 Ps 3: 3.222 |

| C. sinensis | t1: 10.7882 t2: 10.1897 t3: 10.2107 | T1L: 12.4329 T2L: 12.3501 T3L: 11.9363 | Ps 1: 4.7453 Ps 2: 4.8396 Ps 3: 5.2744 |

| S. betaceum | t1: 9.7225 t2: 9.6373 t3: 10.0843 | T1L: 12.7195 T2L: 12.7456 T3L: 13.1384 | Ps 1: 4 Ps 2: 3.8917 Ps 3: 3.9459 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.151 | 0.161 | 0.155 | 0.151 | 1.077 | 1.14 | 1.161 | 1.178 | 0.195 | 0.183 | 0.205 | 0.204 |

| B | 0.278 | 0.304 | 0.294 | 0.28 | 1.174 | 1.099 | 1.191 | 1.244 | 0.213 | 0.233 | 0.215 | 0.203 |

| C | 0.388 | 0.399 | 0.396 | 0.406 | 1.042 | 1.075 | 1.062 | 1.049 | ||||

| D | 0.497 | 0.487 | 0.479 | 0.506 | 0.925 | 0.891 | 0.896 | 0.916 | ||||

| E | 0.624 | 0.634 | 0.627 | 0.656 | 0.819 | 0.823 | 0.755 | 0.821 | ||||

| F | 0.287 | 0.74 | 0.753 | 0.77 | 0.589 | 0.621 | 0.637 | 0.618 | ||||

| G | 0.878 | 0.87 | 0.871 | 0.893 | 0.057 | 0.054 | 0.054 | 0.054 | ||||

| H | 1.051 | 0.896 | 0.883 | 0.898 | 0.221 | 0.229 | 0.233 | 0.239 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.096 | 0.106 | 0.100 | 0.096 | 1.022 | 1.085 | 1.106 | 1.123 |

| B | 0.223 | 0.249 | 0.239 | 0.225 | 1.119 | 1.044 | 1.136 | 1.189 |

| C | 0.333 | 0.344 | 0.341 | 0.351 | 0.987 | 1.020 | 1.007 | 0.994 |

| D | 0.442 | 0.432 | 0.424 | 0.451 | 0.870 | 0.836 | 0.841 | 0.861 |

| E | 0.569 | 0.579 | 0.572 | 0.601 | 0.764 | 0.768 | 0.700 | 0.766 |

| F | 0.232 | 0.685 | 0.698 | 0.715 | 0.534 | 0.566 | 0.582 | 0.563 |

| G | 0.823 | 0.815 | 0.816 | 0.838 | 0.092 | 0.089 | 0.089 | 0.090 |

| H | 0.996 | 0.841 | 0.828 | 0.843 | 0.166 | 0.174 | 0.178 | 0.184 |

| Spectrophotometer Reading | Average | Concentration of Total Polyphenols | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | ABS 1 | ABS 2 | ABS 3 | ABS 4 | ABS Average | TPC (mg GAE/g DW) 1 | TPC (mg GAE/g DW) 2 | TPC (mg GAE/g DW) 3 | Mean ± SD |

| T. cacao 1 | 0.987 | 1.020 | 1.007 | 0.994 | 1.002 | 85.68 | 88.53 | 87.41 | 87.21 ± 1.46 |

| T. cacao 2 | 0.870 | 0.836 | 0.841 | 0.861 | 0.852 | 75.59 | 72.66 | 73.09 | 73.78 ± 1.55 |

| T. cacao 3 | 0.764 | 0.768 | 0.700 | 0.766 | 0.750 | 66.46 | 66.80 | 60.94 | 64.73 ± 3.35 |

| C. sinensis 1 | 1.031 | 0.993 | 1.094 | 1.039 | 1.039 | 349.27 | 335.19 | 372.60 | 352.35 ± 15.29 |

| C. sinensis 2 | 0.919 | 0.942 | 0.900 | 0.920 | 0.920 | 307.79 | 316.31 | 300.75 | 308.28 ± 7.79 |

| C. sinensis 3 | 0.964 | 0.985 | 1.010 | 0.986 | 0.986 | 324.45 | 332.23 | 341.49 | 332.72 ± 8.52 |

| A. cepa 1 | 0.873 | 0.875 | 0.889 | 0.879 | 0.879 | 290.89 | 291.63 | 296.81 | 293.11 ± 3.19 |

| A. cepa 2 | 1.442 | 1.503 | 1.532 | 1.492 | 1.492 | 501.63 | 524.22 | 534.96 | 520.27 ± 17.01 |

| A. cepa 3 | 0.643 | 0.678 | 0.669 | 0.663 | 0.663 | 205.70 | 218.67 | 215.33 | 213.23 ± 6.80 |

| S. betaceum 1 | 0.701 | 0.646 | 0.641 | 0.663 | 0.663 | 227.19 | 206.81 | 204.96 | 212.99 ± 11.82 |

| S. betaceum 2 | 0.352 | 0.331 | 0.365 | 0.349 | 0.349 | 97.93 | 90.15 | 102.74 | 96.94 ± 6.31 |

| S. betaceum 3 | 0.026 | 0.028 | 0.027 | 0.027 | 0.027 | 94.85 | 96.24 | 95.71 | 95.60 ± 0.70 |

| Extract Preparation | Dilution Factor | Concentration of Total Polyphenols | Average | Standard Deviation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g | L | DF | mg GAE/g DW 1 | mg GAE/g DW 2 | mg GAE/g DW 3 | mg GAE/g DW 4 | mg GAE/g DW | SD |

| 8 | 0.05 | 1 | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| 8 | 0.05 | 1 | 0.47 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.01 |

| 8 | 0.05 | 1 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.02 |

| 8 | 0.08 | 1 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.02 |

| 3 | 46.103 | 44.246 | 49.183 | 46.511 | 2.49 | 0.52 | 24.68 | 26.79 |

| 3 | 40.628 | 41.752 | 39.699 | 40.693 | 1.03 | 0.45 | 20.47 | 22.79 |

| 3 | 42.828 | 43.855 | 45.077 | 43.920 | 1.13 | 0.51 | 22.66 | 25.23 |

| 3 | 38.397 | 38.495 | 39.180 | 38.691 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 19.68 | 22.23 |

| 3 | 66.215 | 69.197 | 70.615 | 68.676 | 2.25 | 0.81 | 35.59 | 39.34 |

| 3 | 27.153 | 28.864 | 28.424 | 28.147 | 0.89 | 0.33 | 14.45 | 15.98 |

| 3 | 29.988 | 27.300 | 27.055 | 28.114 | 1.63 | 0.27 | 14.27 | 15.39 |

| 3 | 12.926 | 11.900 | 13.562 | 12.796 | 0.84 | 0.14 | 6.83 | 7.34 |

| 3 | −3.012 | −2.914 | −2.963 | -2.963 | 0.05 | -0.03 | −1.48 | 1.72 |

| Extract | Concentration (µg/mL) | Replica 1 | Replica 2 | Replica 3 | Colony Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. sinensis | 200 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1.67 |

| C. sinensis | 300 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| C. sinensis | 400 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| A. cepa | 200 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3.33 |

| A. cepa | 300 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1.67 |

| A. cepa | 400 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| T. cacao | 200 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2.67 |

| T. cacao | 300 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.00 |

| T. cacao | 400 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| S. betaceum | 200 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4.67 |

| S. betaceum | 300 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2.67 |

| S. betaceum | 400 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.00 |

| Extract | MIC (µg/mL) |

|---|---|

| C. sinensis | 300 |

| A. cepa | 400 |

| T. cacao | 400 |

| S. betaceum | 400 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salazar Llorente, E.J.; Mora, F.J.C.; Carrillo, A.E.A.; Radice, M.; Vásquez Cortez, L.H.; Torres Salvatierra, B.F. Synergistic Antimicrobial Effect of Agro-Industrial Peel Extracts and Saccharomyces cerevisiae Against Listeria monocytogenes in Fruit Juice Matrices. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 5, 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040146

Salazar Llorente EJ, Mora FJC, Carrillo AEA, Radice M, Vásquez Cortez LH, Torres Salvatierra BF. Synergistic Antimicrobial Effect of Agro-Industrial Peel Extracts and Saccharomyces cerevisiae Against Listeria monocytogenes in Fruit Juice Matrices. Applied Microbiology. 2025; 5(4):146. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040146

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalazar Llorente, Enrique José, Fernando Javier Cobos Mora, Aurelio Esteban Amaiquema Carrillo, Matteo Radice, Luis Humberto Vásquez Cortez, and Brayan F. Torres Salvatierra. 2025. "Synergistic Antimicrobial Effect of Agro-Industrial Peel Extracts and Saccharomyces cerevisiae Against Listeria monocytogenes in Fruit Juice Matrices" Applied Microbiology 5, no. 4: 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040146

APA StyleSalazar Llorente, E. J., Mora, F. J. C., Carrillo, A. E. A., Radice, M., Vásquez Cortez, L. H., & Torres Salvatierra, B. F. (2025). Synergistic Antimicrobial Effect of Agro-Industrial Peel Extracts and Saccharomyces cerevisiae Against Listeria monocytogenes in Fruit Juice Matrices. Applied Microbiology, 5(4), 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040146