Beyond Diversity: Functional Microbiome Signatures Linked to Obesity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Data and Sample Processing

2.3. Sequencing of the Bacterial 16S rRNA Genes’ V3 and V4 Hypervariable Regions

2.4. Statistical Methods

2.5. Functional Analysis

2.6. Covariance Network Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Intra and Inter-Individual Gut Microbiome Variation Based on the BMI Categories

3.3. Differential Expressions Show That the Genera Parabacteroides Is the Most Significantly Enriched in the Obese Cohort

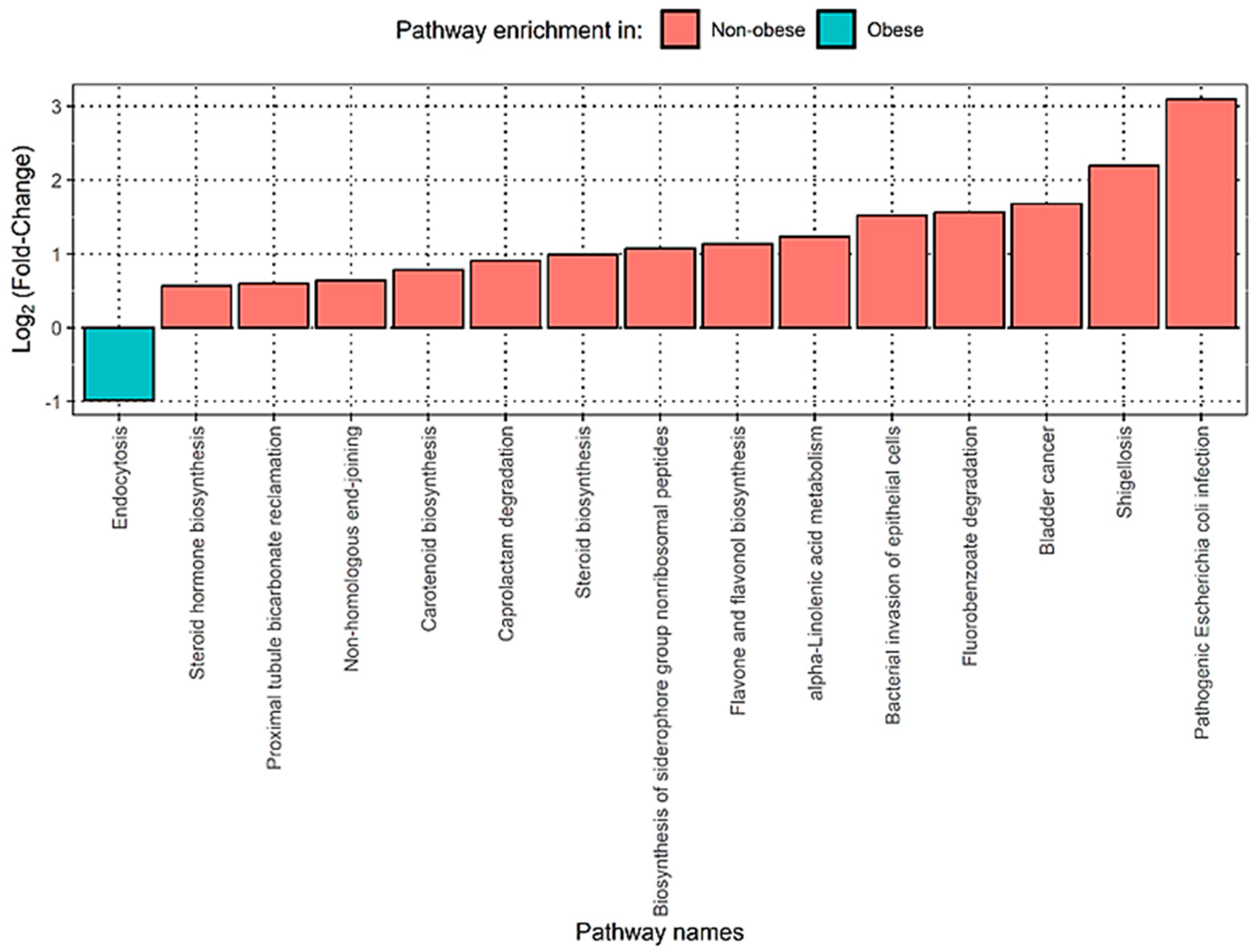

3.4. Functional Analysis Shows That Obese Patients Have Significantly Enriched Pathways Related to Bacterial Infections in the Gut Microbiome

3.5. Covariance Network Analysis Shows That the Genus Alistipes and Bilophia Are the Most Significant Features, Correlated to the Most Metabolic Pathways

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body mass index |

| SCFA | Short-chain fatty acid |

| PICRUSt2 | Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States |

References

- Fan, Y.; Pedersen, O. Gut microbiota in human metabolic health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastogi, S.; Singh, A. Gut microbiome and human health: Exploring how the probiotic genus Lactobacillus modulate immune responses. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1042189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Chen, Y.-T.; Li, K.-Y.; Chen, M.-J. Investigating the mechanistic differences of obesity-inducing Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens M1 and anti-obesity Lactobacillus mali APS1 by microbolomics and metabolomics. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burakova, I.; Smirnova, Y.; Gryaznova, M.; Syromyatnikov, M.; Chizhkov, P.; Popov, E.; Popov, V. The effect of short-term consumption of lactic acid bacteria on the gut microbiota in obese people. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Shataer, D.; Yan, H.; Dong, X.; Zhang, M.; Qin, Y.; Cui, J.; Wang, L. Probiotics and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Unveiling the mechanisms of Lactobacillus plantarum and Bifidobacterium bifidum in modulating lipid metabolism, inflammation, and intestinal barrier integrity. Foods 2024, 13, 2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Shuai, M.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Fu, Y.; Shen, L.; Zheng, J.-S.; Chen, Y.-M. Temporal relationship among adiposity, gut microbiota, and insulin resistance in a longitudinal human cohort. BMC Med. 2022, 20, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Gallausiaux, C.; Marinelli, L.; Blottière, H.M.; Larraufie, P.; Lapaque, N. SCFA: Mechanisms and functional importance in the gut. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2021, 80, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, J.L.; Ley, R.E. The human gut bacteria Christensenellaceae are widespread, heritable, and associated with health. BMC Biol. 2019, 17, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazier, W.; Le Corf, K.; Martinez, C.; Tudela, H.; Kissi, D.; Kropp, C.; Coubard, C.; Soto, M.; Elustondo, F.; Rawadi, G.; et al. A new strain of Christensenella minuta as a potential biotherapy for obesity and associated metabolic diseases. Cells 2021, 10, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safarchi, A.; Al-Qadami, G.; Tran, C.D.; Conlon, M. Understanding dysbiosis and resilience in the human gut microbiome: Biomarkers, interventions, and challenges. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1559521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Jiang, H.; Feng, L.-J.; Jiang, M.-Z.; Wang, Y.-L.; Liu, S.-J. Christensenella minuta interacts with multiple gut bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1301073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikoloski, Z.; Williams, G. Obesity in Middle East, in Metabolic Syndrome; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, G.; Brough, L.; Murphy, R.; Hedderley, D.; Butts, C.; Coad, J. Validity and reproducibility of a habitual dietary fibre intake short food frequency questionnaire. Nutrients 2016, 8, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, B.J.; Mcmurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruesse, E.; Quast, C.; Knittel, K.; Fuchs, B.M.; Ludwig, W.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. SILVA: A comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 7188–7196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, G.M.; Maffei, V.J.; Zaneveld, J.R.; Yurgel, S.N.; Brown, J.R.; Taylor, C.M.; Huttenhower, C.; Langille, M.G.I. PICRUSt2 for prediction of metagenome functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlmann-Eltze, C.; Huber, W. glmGamPoi: Fitting Gamma-Poisson generalized linear models on single cell count data. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 5701–5702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Mai, J.; Cao, X.; Burberry, A.; Cominelli, F.; Zhang, L. ggpicrust2: An R package for PICRUSt2 predicted functional profile analysis and visualization. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahti, L.; Shetty, S. Microbiome R Package; Bioconductor: Seattle, WA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zou, R.; Guo, M.; Zheng, H. Characteristics of gut microbiota in people with obesity. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-H.; Yun, K.E.; Kim, J.; Park, E.; Chang, Y.; Ryu, S.; Kim, H.-L.; Kim, H.-N. Gut microbiota and metabolic health among overweight and obese individuals. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Chatelier, E.; Nielsen, T.; Qin, J.; Prifti, E.; Hildebrand, F.; Falony, G.; Almeida, M.; Arumugam, M.; Batto, J.-M.; Kennedy, S.; et al. Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. Nature 2013, 500, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, W.; Lorenzo, M.B.; Cintoni, M.; Porcari, S.; Rinninella, E.; Kaitsas, F.; Lener, E.; Mele, M.C.; Gasbarrini, A.; Collado, M.C.; et al. Short-chain fatty-acid-producing bacteria: Key components of the human gut microbiota. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, Q.; Yang, Y.; Guo, A. Biological function of short-chain fatty acids and its regulation on intestinal health of poultry. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 736739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Companys, J.; Gosalbes, M.J.; Pla-Pagà, L.; Calderón-Pérez, L.; Llauradó, E.; Pedret, A.; Valls, R.M.; Jiménez-Hernández, N.; Sandoval-Ramirez, B.A.; del Bas, J.M.; et al. Gut microbiota profile and its association with clinical variables and dietary intake in overweight/obese and lean subjects: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liébana-García, R.; López-Almela, I.; Olivares, M.; Romaní-Pérez, M.; Manghi, P.; Torres-Mayo, A.; Tolosa-Enguís, V.; Flor-Duro, A.; Bullich-Vilarrubias, C.; Rubio, T.; et al. Gut commensal Phascolarctobacterium faecium retunes innate immunity to mitigate obesity and metabolic disease in mice. Nat. Microbiol. 2025, 10, 1310–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myhrstad, M.C.W.; Tunsjø, H.; Charnock, C.; Telle-Hansen, V.H. Dietary fiber, gut microbiota, and metabolic regulation—Current status in human randomized trials. Nutrients 2020, 12, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavella, T.; Rampelli, S.; Guidarelli, G.; Bazzocchi, A.; Gasperini, C.; Pujos-Guillot, E.; Comte, B.; Barone, M.; Biagi, E.; Candela, M.; et al. Elevated gut microbiome abundance of Christensenellaceae, Porphyromonadaceae and Rikenellaceae is associated with reduced visceral adipose tissue and healthier metabolic profile in Italian elderly. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1880221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Y.; Qin, X.; Jia, H.; Chen, S.; Sun, W.; Wang, X. The association between gut microbiota composition and BMI in Chinese male college students, as analysed by next-generation sequencing. Br. J. Nutr. 2019, 122, 986–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Lin, T.-C.; Yang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Sibeko, L.; Liu, Z. High-fat diet during early life reshapes the gut microbiome and is associated with the disrupted mammary microenvironment in later life in mice. Nutr. Res. 2024, 127, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| BMI < 30 (Non-Obese) N = 75 | BMI > 30 (Obese) N = 28 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.90 ‡ | ||

| Male | 35 | 12 | |

| Female | 40 | 16 | |

| Age | 0.19 † | ||

| age < 30 | 25 | 6 | |

| 30 ≤ age < 65 | 43 | 18 | |

| 65 ≥ age | 7 | 4 | |

| Fiber diet | 0.31 ‡ | ||

| High | 30 | 15 | |

| Low | 45 | 13 | |

| Probiotics | 1.00 ‡ | ||

| Yes | 30 | 11 | |

| No | 45 | 17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almomani, W.; Al-Tawalbeh, D.; Alwaqfi, K.; BaniHani, A.; Abuirsheid, L.; Ayasreh, R.; BaniHani, M.; Barreiros, A.; Albataineh, M. Beyond Diversity: Functional Microbiome Signatures Linked to Obesity. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 5, 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040141

Almomani W, Al-Tawalbeh D, Alwaqfi K, BaniHani A, Abuirsheid L, Ayasreh R, BaniHani M, Barreiros A, Albataineh M. Beyond Diversity: Functional Microbiome Signatures Linked to Obesity. Applied Microbiology. 2025; 5(4):141. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040141

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmomani, Waleed, Deniz Al-Tawalbeh, Khaled Alwaqfi, Ali BaniHani, Lujain Abuirsheid, Raghad Ayasreh, Mohammad BaniHani, Andre Barreiros, and Mohammad Albataineh. 2025. "Beyond Diversity: Functional Microbiome Signatures Linked to Obesity" Applied Microbiology 5, no. 4: 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040141

APA StyleAlmomani, W., Al-Tawalbeh, D., Alwaqfi, K., BaniHani, A., Abuirsheid, L., Ayasreh, R., BaniHani, M., Barreiros, A., & Albataineh, M. (2025). Beyond Diversity: Functional Microbiome Signatures Linked to Obesity. Applied Microbiology, 5(4), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040141