Advances in Rice Agronomic Technologies in Latin America in the Face of Climate Change

Abstract

1. Introduction

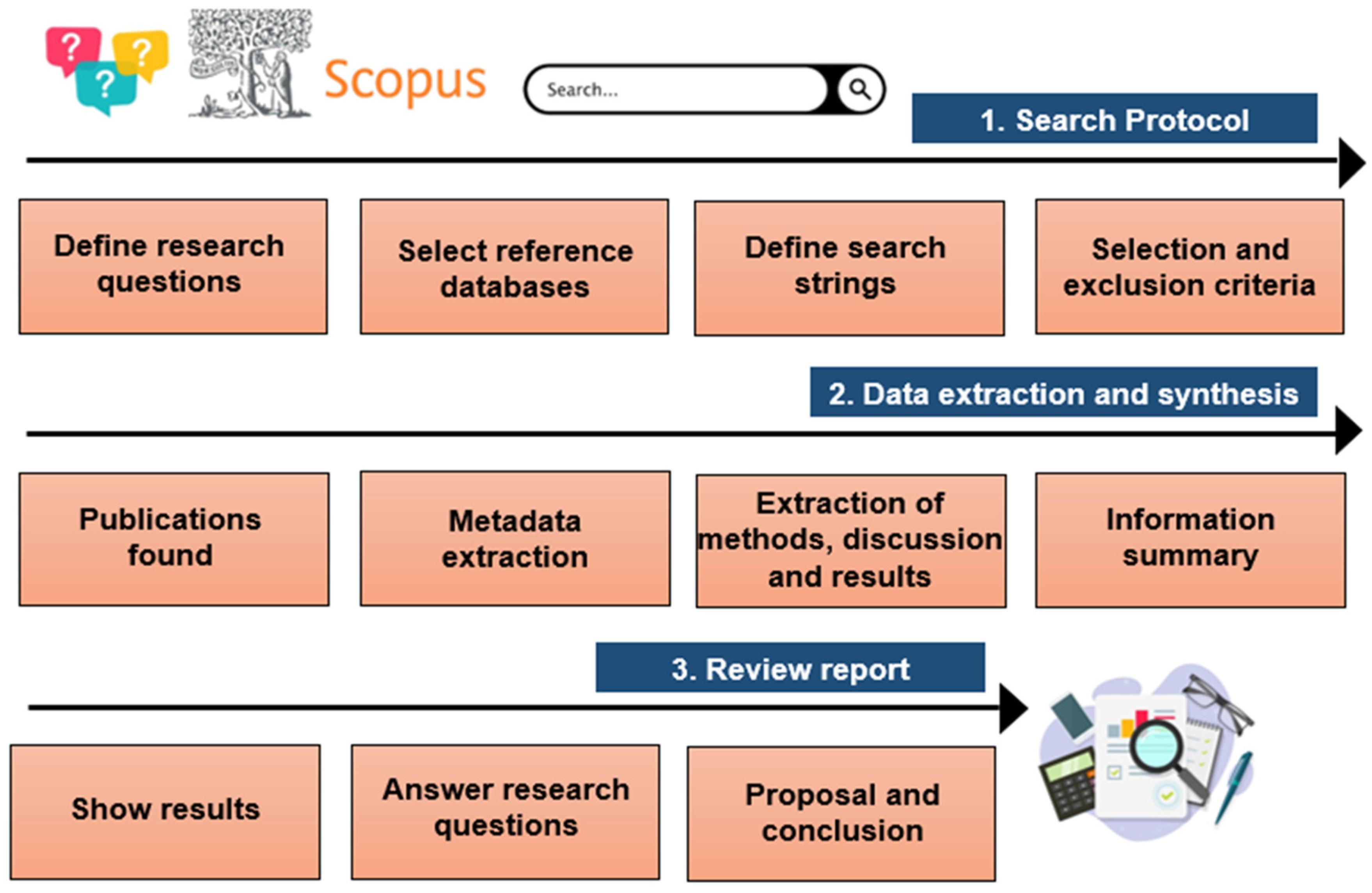

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Protocol

2.2. Research Questions

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Exclusion and Selection Criteria

2.5. Reference Database

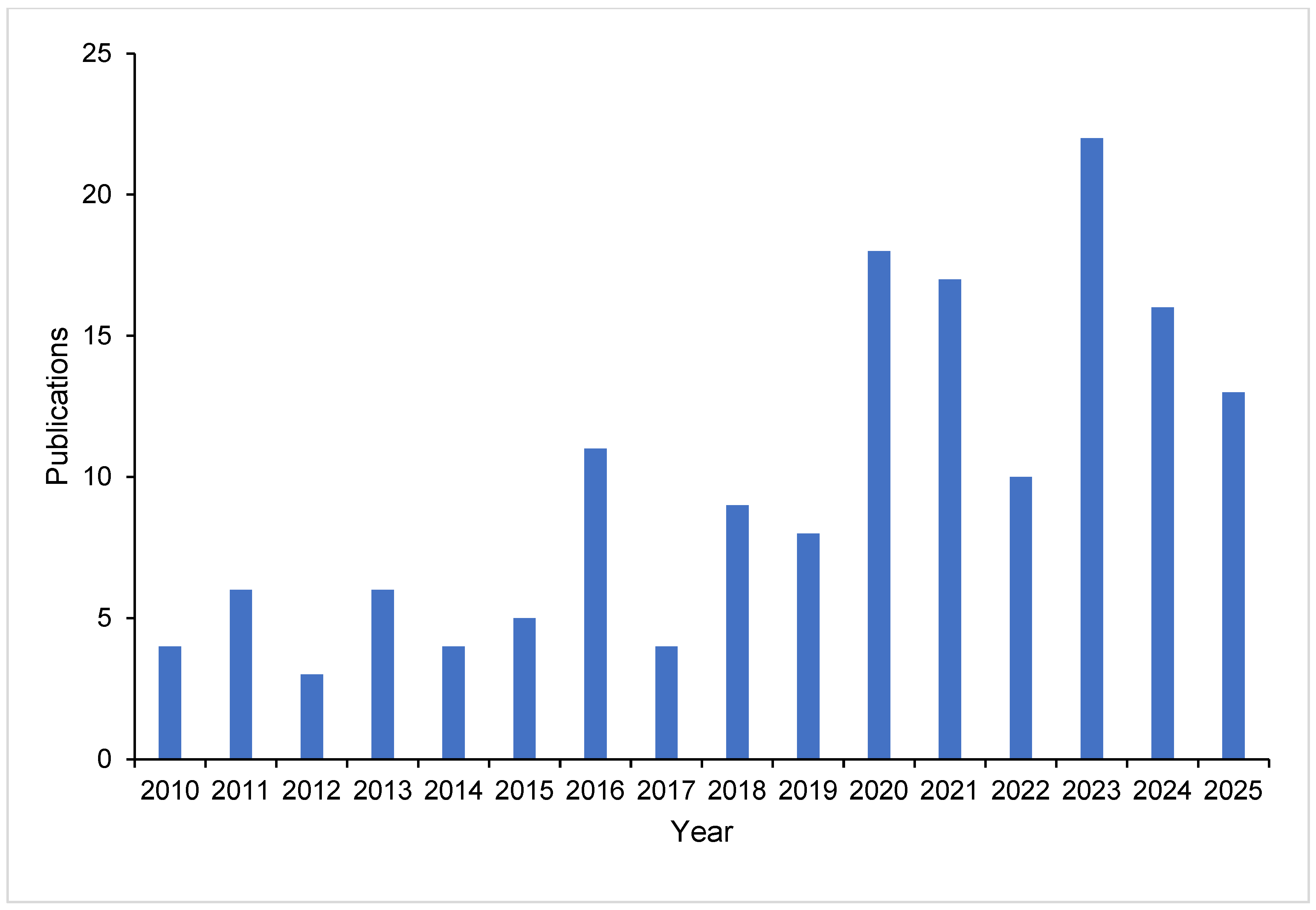

3. Results

3.1. Major Problems and Overall Technological Advance for Rice Production in Latin America

3.2. Precision Agriculture and Rice Simulation Models in Latin America

3.3. Genetic Improvement of Rice in Latin America

3.4. Water Management and Irrigation in Rice Cultivation in Latin America

3.5. Nutrition and Fertilization Management in Rice Cultivation in Latin America

3.6. Pest and Weed Control in Rice Crops in Latin America

3.7. Technological Advances Trends by Country in Rice Production

4. Discussion

4.1. Research Gaps and Future Directions

4.2. Recommendations for Researchers, Decision Makers, and Farmers

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization for the United Nations. FAOSTAT Data Base. 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/es/#data/QCL (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Yamano, T.; Arouna, A.; Labarta, R.A.; Huelgas, Z.M.; Mohanty, S. Adoption and impacts of international rice research technologies. Glob. Food Secur. 2016, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, P.Y. Development of hybrid rice to ensure food security. Rice Sci. 2014, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bermúdez, M.; Del Pozo, J.C.; Pernas, M. Effects of combined abiotic stresses related to climate change on root growth in crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 918537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Hernández, M.B.; López-Castañeda, C.; Kohashi-Shibata, J.; Miranda-Colín, S.; Barrios-Gómez, E.J.; Martínez-Rueda, C.G. Drought and heat tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa). Ecosistemas Recur. Agropecu. 2018, 5, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slob, N.; Catal, C.; Kassahun, A. Application of machine learning to improve dairy farm management: A systematic literature review. Prev. Vet. Med. 2021, 187, 105237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S.; Budgen, D.; Brereton, P.; Turner, M.; Linkman, S.; Visaggio, G. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering; Keele University: Keele, UK; University of Durham: Durham, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Van Klompenburg, T.; Kassahun, A.; Catal, C. Crop yield prediction using machine learning: A systematic literature review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 177, 105709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Dou, F.; Morgan, C.L.; Guo, J.; Deng, J.; Schwab, P. Modeling organically fertilized flooded rice systems and its long-term effects on grain yield and methane emissions. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, V.A.; Brasil, E.P.F.; Teixeira, W.G.; Santos, F.D.; Silva, A.D. Yield response of upland rice as influenced by enhanced-efficiency nitrogen fertilizers in the Brazilian Cerrado. J. Agric. Sci. 2020, 12, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochnow, M.H.; Marchesan, E.; Fleck, G.; Riste, U.S.; Cassanego, E.I.; Pfeifer, J.G. Irrigation start time in organic rice production system. Rev. Ciências Agrárias 2021, 44, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, J.A.S.; Marchesan, E.; Giacomini, S.J.; Grohs, M.; Taschetto, Â.M.; Fortuna, C.R.; Donato, G. Emission of greenhouse gases and yield-scaled global warming potential of rice cultivars under permanent and intermittent irrigation. Bragantia 2022, 81, e2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Fernández, L.; Quispe-Tito, D.; Altamirano-Gutiérrez, L.; Cruz-Grimaldo, C.; Quille-Mamani, J.A.; Carbonell-Rivera, J.P.; Torralba, J.; Ruiz, L.Á. Estimation of evapotranspiration from high-resolution UAV imagery for irrigation systems in rice fields on the northern coast of Peru. Sci. Agropecu. 2024, 15, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinemann, A.B.; Barrios-Pérez, C.; Ramírez-Villegas, J.; Arango-Londoño, D.; Bonilla-Findji, O.; Medeiros, J.C.; Jarvis, A. Variation and impact of drought-stress patterns across upland rice target population of environments in Brazil. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, e126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombari Filho, J.M.; de Resende, M.D.V.; de Morais, O.P.; de Castro, A.P.; Guimaraes, E.P.; Pereira, J.A.; Breseghello, F. Upland rice breeding in Brazil: A simultaneous genotypic evaluation of stability, adaptability and grain yield. Euphytica 2013, 192, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, T.V.D.; Fontana, D.C.; Alves, R.C.M. Evaluation of heat fluxes and evapotranspiration using SEBAL model with data from ASTER sensor. Pesqui. Agropecuária Bras. 2010, 45, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, F.A.S.; Fonseca, L.M.; Bendini, H.D.N. Mapping irrigated rice in Brazil using Sentinel-2 spectral–temporal metrics and random forest algorithm. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisóstomo de Castro Filho, H.; Abílio de Carvalho Júnior, O.; Ferreira de Carvalho, O.L.; Pozzobon de Bem, P.; dos Santos de Moura, R.; Olino de Albuquerque, A.; Rosa Silva, C.; Guimarães Ferreira, P.H.; Fontes Guimarães, R.; Trancoso Gomes, R.A. Rice Crop Detection Using LSTM, Bi-LSTM, and Machine Learning Models from Sentinel-1 Time Series. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Villamor, L.; Hardy, A.; Bunting, P.; Llanos-Peralta, W.; Zamora, M.; Rodriguez, Y.; Gomez-Latorre, D.A. The Earth Observation-based Anomaly Detection (EOAD) system: A simple, scalable approach to mapping in-field and farm-scale anomalies using widely available satellite imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 104, 102535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarro-Espinal, I.; Huanuqueño-Murillo, J.; Quille-Mamani, J.; Quispe-Tito, D.; Ramos-Fernández, L.; Pino-Vargas, E.; Torres-Rua, A. Field-Scale rice yield prediction in Northern Coastal Region of Peru Using Sentinel-2 vegetation indices and machine learning models. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Medina, A.J.; Salas-López, R.; Zabaleta-Santisteban, J.A.; Tuesta-Trauco, K.M.; Turpo-Cayo, E.Y.; Huaman-Haro, N.; Gómez-Fernández, D. An analysis of the rice-cultivation dynamics in the lower Utcubamba river basin using SAR and optical imagery in Google Earth Engine (GEE). Agronomy 2024, 14, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Fernández, L.; Peña-Amaro, R.; Huanuqueño-Murillo, J.; Quispe-Tito, D.; Maldonado-Huarhuachi, M.; Heros-Aguilar, E.; Torres-Rua, A. Water use efficiency in rice under alternative wetting and drying technique using energy balance model with UAV information and Aquacrop in Lambayeque, Peru. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quille-Mamani, J.; Ramos-Fernández, L.; Huanuqueño-Murillo, J.; Quispe-Tito, D.; Cruz-Villacorta, L.; Pino-Vargas, E.; Ángel Ruiz, L. Rice yield prediction using spectral and textural indices derived from UAV imagery and machine learning models in Lambayeque, Peru. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Cartagena, A.; Mejia-Cabrera, H.I.; Arcila-Diaz, J. Detection of Tagosodes orizicolus in aerial images of rice crops using machine learning. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.S.; Cicero, S.M.; Silva, F.F.D.; Gomes-Junior, F.G. X-ray, multispectral and chlorophyll fluorescence images: Innovative methods for evaluating the physiological potential of rice seeds. J. Seed Sci. 2023, 45, e202345003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Garza, T.; Gómez-Merino, F.C.; Trejo-Téllez, L.I.; Muñoz-Orozco, A.; Tavitas-Fuentes, L.; Hernández-Aragón, L.; Santacruz-Varela, A. Physiological and nutritional responses of rice varieties to aluminum concentration. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 2010, 33, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Barrios-Gómez, E.J.; González, G.F.; Canul-Ku, J.; Hernández-Arenas, M. Evaluation of advanced coarse grain rice lines in Morelos, Mexico. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agrícolas 2016, 7, 1091–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Hernández, J.C.; Tapia-Vargas, L.M.; Hernández-Aragón, L.; Tavitas-Fuentes, L.; Apaez-Barrios, M. Production potential of rice ‘Lombardy FLAR 13’ long and thin grain genotype from the rice-growing area of Michoacán. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agrícolas 2022, 13, 1117–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Aragón, L.; Tavitas-Fuentes, L.; Álvarez-Hernandez, J.C.; De La O-Olán, M. Origin and characteristics of rice genetic diversity in Mexico. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 2023, 46, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Aragón, L.; Tavitas-Fuentes, L. Rice in Mexico Technical Book No. 14; National Institute of Forestry, Agricultural and Livestock Research (INIFAP): Zacatepec, Mexico, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Butts, T.R.; Davis, B.M.; Houston, M.; Norsworthy, J.K.; Scott, R.C.; Barber, L.T. Pest Management: Weeds; Arkansas Rice Research Studies: Stuttgart, AR, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cristo-Valdés, E.; González, M.C.; Ventura, E.; Rodríguez, A.T. Effect of salinity in the initial stages of the development of three rice cultivars (Oryza sativa L.). Cultiv. Trop. 2018, 39, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Cobos-Mora, F.; Gómez-Pando, L.R.; Reyes-Borja, W.O.; Ruilova-Cueva, M.; Medina-Litardo, R.C.; Hufana-Duran, D. Selecting advanced rice lines (Oryza sp.) as an alternative for sustainable management of soils degraded by salinity. Cienc. Tecnol. Agropecu. 2022, 23, e2398. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, M.; Arbelaez, J.D.; Loaiza, K.; Cuasquer, J.; Rosas, J.; Graterol, E. Genetic and phenotypic characterization of rice grain quality traits to define research strategies for improving rice milling, appearance, and cooking qualities in Latin America and the Caribbean. Plant Genome 2021, 14, e20134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soremi, P.A.S.; Chirinda, N.; Graterol, E.; Alvarez, M.F. Potential of rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars to mitigate methane emissions from irrigated systems in Latin America and the Caribbean. All Earth 2023, 35, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira de Castro, A.; Breseghello, F.; Furtini, I.V.; Utumi, M.M.; Pereira, J.A.; Cao, T.V.; Bartholomé, J. Population improvement via recurrent selection drives genetic gain in upland rice breeding. Heredity 2023, 131, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piveta, L.B.; Roma-Burgos, N.; Noldin, J.A.; Viana, V.E.; Oliveira, C.D.; Lamego, F.P.; Avila, L.A.D. Molecular and physiological responses of rice and weedy rice to heat and drought stress. Agriculture 2020, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondi, J.V.; Marschalek, R.; Nodari, R.O. Genetic base of paddy rice cultivars of Southern Brazil. Crop Breed. Appl. Biotechnol. 2014, 14, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, R.; Angira, B.; Kongchum, M.; Famoso, A.N. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of grain quality in US and Latin American rice and implications for breeding. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 7159–7168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Almeida, I.; Navia-Pesantes, O.; Celi-Herán, R. Assessment of rice amylose content and grain quality through marker-assisted selection. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2025, 16, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, Y.S.; Silva, M.A.S.D.; Correchel, V.; Santos, A.B.D.; Carvalho, M.T.D.M.; Madari, B.E.; Caetano, P.H.P. Emission of nitrous oxide in flooded rice cultivation in tropical area of Brazil. Pesqui. Agropecuária Bras. 2020, 55, e01497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.A.B.; Parfitt, J.M.B.; Timm, L.C.; Faria, L.C.; Concenço, G.; Stumpf, L.; Nörenberg, B.G. Sprinkler irrigation in lowland rice: Crop yield and its components as a function of water availability in different phenological phases. Field Crops Res. 2020, 248, 107714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echegaray-Cabrera, I.; Cruz-Villacorta, L.; Ramos-Fernández, L.; Bonilla-Cordova, M.; Heros-Aguilar, E.; Flores del Pino, L. Effect of Alternate Wetting and Drying on the Emission of Greenhouse Gases from Rice Fields on the Northern Coast of Peru. Agronomy 2024, 14, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedeño-Plaza, J.W.; Campoverde, J.M.Q.; Montealegre, V.J.G.; Unda, S.A.B.; Aguilar, M.A.E. Economic comparison between the traditional system and the intensive system of rice production in Ecuador. South Fla. J. Dev. 2022, 3, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccetto, S.; Capurro, M.C.; Roel, Á. Strategies to minimize rice crop water consumption in Uruguay while maintaining its productivity. Agrociencia Urug. 2017, 21, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loaiza, S.; Verchot, L.; Valencia, D.; Guzmán, P.; Amezquita, N.; Garcés, G.; Pittelkow, C.M. Evaluating greenhouse gas mitigation through alternate wetting and drying irrigation in Colombian rice production. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 360, 108787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Borja Reis, A.F.; de Almeida, R.E.M.; Lago, B.C.; Trivelin, P.C.; Linquist, B.; Favarin, J.L. Aerobic rice system improves water productivity, nitrogen recovery and crop performance in Brazilian weathered lowland soil. Field Crops Res. 2018, 218, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil, M.D.S.; Souza, M.S.T.D.; Guimarães, S.L.; Koswoski, S.L.; Batistela, M.W.A. Initial development of upland rice plants inoculated with the MAY12 strain of Azospirillum spp. Cienc. Rural 2021, 51, e20200824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Ramirez, L.F.; Uribe-Velez, D. Phosphorus solubilizing and mineralizing Bacillus spp. contribute to rice growth promotion using soil amended with rice straw. Curr. Microbiol. 2021, 78, 932–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa-Garcia, A.; Cordero, A.P.; Vergara, D.E.M. Bioprospecting of Endophytic Bacteria with Plant Growth Promoting Activity Associated with Rice Varieties From The Colombian Caribbean. J. Namib. Stud. Hist. Politics Cult. 2022, 32, 193–216. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, I.S.; Moran, W.E.; Antonio, Á.M.; Darlyn, A.M. Effectiveness of biopreparations in rice fertilization in the canton of Nobol (Guayas, Ecuador). J. Surv. Fish. Sci. 2023, 10, 693–702. [Google Scholar]

- Arévalo-Aranda, Y.; Rodríguez, T.E.; Rosillo, C.L.; Díaz-Chuquizuta, H.; Torres, C.E.E.; Cruz-Luis, J.; Siqueira, B.R.C.; Pérez, W.E. Green manuring and fertilization on rice cultivation: A peruvian Amazon study. Rev. FCA UNCuyo 2024, 56, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleck, A.G.; Marchesan, E.; Schlosser, J.F.; Oliveira, D.S.D.; Prochnow, M.H.; Soares, C.F.; Herzog, D. Soil deep tillage performed before soybean cultivation on the rice cultivation in the following harvest. Cienc. Rural 2022, 53, e20210621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savi, D.; Zimmermann, G.G.; Jasper, S.P.; Sobenko, L.R. Use of graphite in the distribution of rice seeds with constant flow seed metering device. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agríc. Ambient. 2023, 27, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, R.O.D.; Carlos, F.S.S.; Silva, L.S.D.; Scivittaro, W.B.; Ribeiro, P.L.; Lima, C.L.R.D. No-tillage for flooded rice in Brazilian subtropical paddy fields: History, challenges, advances and perspectives. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo 2021, 45, e0210102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camero, A.S.; Maqueira López, L.A.; Torres de la Noval, W.; Pozo, A.L.; Torres, K. Growth behavior of two rice cultivars at different sowing dates and its influence on yield. Advances 2014, 16, 306–316. [Google Scholar]

- Maqueira López, L.A.; Torres de la Nova, W.; Pérez, M.S.A.; Díaz, P.D.; Roján, H.O. Influence of environmental temperature and sowing date on the duration of phenological phases in four rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars. Trop. Crops 2016, 37, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quevedo-Amaya, Y.M.; Beltrán-Medina, J.I.; Hoyos-Cartagena, J.Á.; Calderón-Carvajal, J.E.; Barragán-Quijano, E. Sowing date selection and biofertilization as alternatives to improve yield and profitability of rice variety F68. Colomb. Agron. 2020, 38, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Antón, A.A.; Hernández-Herrera, R.M.; González-González, M. Bioactive seaweed extracts as biostimulants for plant growth and protection. Plant Biotechnol. 2020, 20, 257–282. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Pedroso, A.T.; Ramírez-Arrebato, M.Á.; Falcón-Rodríguez, A.; Bautista-Baños, S.; Ventura-Zapata, E.; Valle-Fernández, Y. Effect of Quitomax® on yield and its components of rice cultivar (Oryza sativa L.) var. INCA LP 5. Trop. Crops 2017, 38, 156–159. [Google Scholar]

- Pico, Y.A.B.; Paz, R.A.O.; Rayo, S.L. Optimizing Iron, Manganese, and Zinc Fertilization in Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Through Bacillus, Pseudomonas, and Azospirillum bacteria. Rev. Fac. De Cienc. Básicas 2022, 18, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Litardo, R.C. Technological Alternatives to Mitigate Salinity Effects on Rice (Oryza sativa L.) in San Jacinto de Yaguachi, Ecuador; National Agrarian University: La Molina, Ecuador, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ríos-Ruiz, W.F.; Torres-Chávez, E.E.; Torres-Delgado, J.; Rojas-García, J.C.; Bedmar, E.J.; Valdez-Nuñez, R.A. Inoculation of bacterial consortium increases rice yield (Oryza sativa L.) reducing applications of nitrogen fertilizer in San Martin region, Peru. Rhizosphere 2020, 14, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, C.B.; Islam, A.; Mohammad-Malek, A.; Pakrashi, D.; Ruthbah, U. Experimental evidence on adoption and impact of the system of rice intensification. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2021, 104, 4–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, G.; Hoyos, V.; Vázquez-García, J.G.; Alcántara-de la Cruz, R.; De Prado, R. First case of multiple resistance to EPSPS and PSI in Eleusine indica (L.) Gaertn. collected in rice and herbicide-resistant crops in Colombia. Agronomy 2021, 11, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furcal-Beriguete, P.; Herrera-Barrantes, A. Efecto del silicio y plaguicidas en la fertilidad del suelo y rendimiento del arroz. Agron. Mesoam. 2013, 24, 12537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camino, M.I.A. Evaluation of Systemic Herbicides in the Control of Cyperaceous Weeds in Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Crop, Under Rainfed Conditions. Bachelor’s Thesis, UTB, Babahoyo, Ecuador, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, F.; Agüero, A.R. Control of flatsedge (Cyperus iria L.) in rice. Agron. Mesoam. 2016, 6, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esqueda-Esquivel, V.A.; Tosquy-Valle, O.H. Chemical control of propanil-resistant Echinochloa colona (L.) Link and Cyperus iria L. in rainfed rice (Oryza sativa L.) in Tres Valles, Veracruz. Univ. Y Cienc. 2013, 29, 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Plaza, G.; Hernández, F.A. Effect of zone and crops rotation on Ischaemum rugosum and resistance to bispyribac-sodium in Ariari, Colombia. Planta Daninha 2014, 32, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, J.G.; Plaza, G. Effect of post-emergence herbicide applications on rice crop weed communities in Tolima, Colombia. Planta Daninha 2015, 33, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzenbacher, F.D.O.; Kalsing, A.; Dalazen, G.; Markus, C.; Merotto, A., Jr. Antagonism is the predominant effect of herbicide mixtures used for imidazolinone-resistant barnyardgrass (Echinochloa crus-galli) control. Planta Daninha 2015, 33, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, D.S.; Oliveira, N.A.M.; Noldin, J.A.; Vanti, R.M. Barnyardgrass with multiple resistance to synthetic auxin, ALS and ACCase inhibitors. Planta Daninha 2016, 34, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, P.D.; Peñaherrera, L.A.; Bustos, R.D.; Raffo, L.A.; Yanniccari, M.E. First case of resistance to bispyribac-sodium in barnyardgrass (Echinochloa crus-galli) from Ecuador. Adv. Weed Sci. 2025, 43, e020250098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, B.; Silva, R.M.D.; Luz, V.K.D.; Sousa, R.O.D.; Magalhães Júnior, A.M.D.; Barbosa, N.J.F.; Oliveira, A.C.D. Identificação de famílias mutantes de arroz com tolerância ao frio. Pesqui. Agropecuária Bras. 2024, 59, e03408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colorado, J.D.; Cera-Bornacelli, N.; Caldas, J.S.; Petro, E.; Rebolledo, M.C.; Cuellar, D.; Calderon, F.; Mondragon, I.F.; Jaramillo-Botero, A. Estimation of Nitrogen in Rice Crops from UAV-Captured Images. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Reyes, R.A.; Ruíz-Pérez, M.E. Relationship of Organic Matter Content with Spectral Indices in Soil Dedicated to Rice Cultivation. J. Cienc. Técnicas Agropecu. 2023, 32, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Barona, M.A.; Díaz, R.S.; Suárez, R.R. Adaptability and grain yield stability of rice hybrids and varieties in Venezuela. Bioagro 2021, 33, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Siaca, L.G.; Coe, R.; Quick, W.P.; Long, S.P. Evaluating natural variation, heritability, and genetic advance of photosynthetic traits in rice (Oryza sativa). Plant Breed. 2021, 140, 754–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Reinoso, A.D.; Garces-Varon, G.; Restrepo-Diaz, H. Biochemical and physiological characterization of three rice cultivars under different daytime temperature conditions. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2014, 74, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Huang, J.; Huang, J.; Ahmad, S.; Nanda, S.; Anwar, S.; Shakoor, A.; Zhu, C.; Zhu, L.; Cao, X.; et al. Rice production under climate change: Adaptations and mitigating strategies. In Environment, Climate, Plant and Vegetation Growth; Fahad, S., Hasanuzzaman, M., Alam, M., Ullah, H., Saeed, M., Khan, A., Adnan, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 659–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarin, A.S.; Islam, M.M.; Rahat, A.; Ahmed, S.; Ghosh, P.; Murata, Y. Drought stress tolerance in rice: Physiological and biochemical insights. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2024, 15, 692–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Han, M.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, C.; Ma, Y. Flooding tolerance of rice: Regulatory pathways and adaptive mechanisms. Plants 2024, 13, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carracelas, G.; Hornbuckle, J.; Rosas, J.; Roel, A. Irrigation management strategies to increase water productivity in Oryza sativa (rice) in Uruguay. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 222, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Amgain, N.R.; Rabbany, A.; Manirakiza, N.; Bai, X.; VanWeelden, M.; Bhadha, J.H. Assessing flood-depth effects on water quality, nutrient uptake, carbon sequestration, and rice yield cultivated on Histosols. Clim. Smart Agric. 2024, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, E.H.F.M.; Hoogenboom, G.; Boote, K.J.; Cuadra, S.V.; Porter, C.H.; Scivittaro, W.B.; Cerri, C.E.P. Implications of water management on methane emissions and grain yield in paddy rice: A case study under subtropical conditions in Brazil using the CSM-CERES-Rice model. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 307, 109234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Cai, D.; Bai, J.; Xu, T.; Yu, F. Intelligent rice field weed control in precision agriculture: From weed recognition to variable rate spraying. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prova, N.N.I. Enhancing agricultural research with an attention-based hybrid model for precise classification of rice varieties. Int. J. Cogn. Comput. Eng. 2025, 6, 412–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klering, V.E.; Cybis, F.D.; Serafini, R.V.; Marques-Alves, R.C.; Berlato, M.A. Modelo agrometeorológico-espectral para estimativa da produtividade de grãos de arroz irrigado no Rio Grande do Sul. Bragantia 2016, 75, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.D.B.; Sanches, I.D.A.; Prudente, V.H.R.; Trabaquini, K. Characterization of Irrigated Rice Cultivation Cycles and Classification in Brazil Using Time Series Similarity and Machine Learning Models with Sentinel Imagery. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machaca-Pillaca, R.; Pino-Vargas, E.; Ramos-Fernández, L.; Quille-Mamani, J.; Torres-Rua, A. Estimación de la evapotranspiración con fines de riego en tiempo real de un olivar a partir de imágenes de un dron en zonas áridas, caso La Yarada, Tacna, Perú. Idesia 2022, 40, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijada, F.; Salazar, C.; Cabas, J. Technical efficiency, production risk and sharecropping: The case of rice farming in Chile. Lat. Am. Econ. Rev. 2022, 31, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, J.M.; Labarta, R.A.; Gonzalez, C.; Lopera, D.C. Joint adoption of rice technologies among Bolivian farmers. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2021, 50, 252–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, P.; Wirsenius, S.; Searchinger, T.; Andrieu, N.; Vogt-Schilb, A. Options to Achieve Net-Zero Emissions from Agriculture and Land Use Changes in Latin America and the Caribbean (No. IDB-WP-01377); IDB Working Paper Series; Inter-American Development Bank (IDB): Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gitti, D.D.C.; Arf, O.; Portugal, J.R.; Corsini, D.C.D.C.; Rodrigues, R.A.F.; Kaneko, F.H. Cover crops, nitrogen rates and seeds inoculation with Azospirillum brasilense in upland rice under no-tillage. Bragantia 2012, 71, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattos, M.L.T.; Valgas, R.A.; Martins, J.F.D.S. Evaluation of the agronomic efficiency of Azospirillum brasilense strains Ab-V5 and Ab-V6 in flood-irrigated rice. Agronomy 2022, 12, 3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, E.C.; Muraoka, T.; Bastos, A.V.S.; Franzin, V.I.; Buzetti, S.; Soares, F.A.L.; Bendassolli, J.A. Biomass and nutrient accumulation by cover crops and upland rice grown in succession under no-tillage system as affected by nitrogen fertilizer rate. J. Crop Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 23, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, V.; Kamoshita, A.; Lopez-Galvis, L.; Pineda, D. Ecophysiology of drill-seeded rice under reduced nitrogen fertilizer and reduced irrigation during El Niño in Central Colombia. Plant Prod. Sci. 2021, 24, 418–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibt, T.A.; Boller, W.; Ulguim, A.D.R.; Avila, R.C.; Lopes, L.D.L.; Melo, A.A. Herbicide florpyrauxifen-benzyl via drone with different nozzles and spray volumes for weed control in rice crops. Ciência Rural 2025, 55, e20240187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.T.; Shimada, K. The effects of climate smart agriculture and climate change adaptation on the technical efficiency of rice farming—An empirical study in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam. Agriculture 2019, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Feng, X.; Lu, C. The rise of smart agriculture in China: Current situation and suggestions for further development. Exp. Agric. 2024, 60, e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Nanseki, T.; Chomei, Y.; Kuang, J. A review of smart agriculture and production practices in Japanese large-scale rice farming. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 1609–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, M.H.; Waza, S.A.; Shukla, S.; Zaidi, N.W.; Nayak, S.; Hossain, M.; Singh, U.S. Drought tolerant rice for ensuring food security in Eastern India. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | NIP | NPAC | PP (%) | ECA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scopus | 466 | 82 | 51.6 | 1, 2, 4–6 |

| Google Scholar | 474 | 55 | 34.6 | 1, 2, 4–6 |

| Science Direct | 192 | 12 | 7.5 | 1–6 |

| Springer Link | 88 | 7 | 4.4 | 1–6 |

| Web of science | 22 | 2 | 1.3 | 4, 5 |

| Wiley | 11 | 1 | 0.6 | 1–6 |

| Total | 1253 | 159 | 100.0 | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Salgado-Velázquez, S.; Barrios-Gómez, E.; Hernández-Aragón, L.; Hernández-Lara, P.U.; Olvera-Rincón, F.; Sumano-López, D.; Inurreta-Aguirre, H.D.; Palma-Cancino, D.J. Advances in Rice Agronomic Technologies in Latin America in the Face of Climate Change. Crops 2026, 6, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/crops6010008

Salgado-Velázquez S, Barrios-Gómez E, Hernández-Aragón L, Hernández-Lara PU, Olvera-Rincón F, Sumano-López D, Inurreta-Aguirre HD, Palma-Cancino DJ. Advances in Rice Agronomic Technologies in Latin America in the Face of Climate Change. Crops. 2026; 6(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/crops6010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalgado-Velázquez, Sergio, Edwin Barrios-Gómez, Leonardo Hernández-Aragón, Pablo Ulises Hernández-Lara, Fabiola Olvera-Rincón, Dante Sumano-López, Hector Daniel Inurreta-Aguirre, and David Julián Palma-Cancino. 2026. "Advances in Rice Agronomic Technologies in Latin America in the Face of Climate Change" Crops 6, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/crops6010008

APA StyleSalgado-Velázquez, S., Barrios-Gómez, E., Hernández-Aragón, L., Hernández-Lara, P. U., Olvera-Rincón, F., Sumano-López, D., Inurreta-Aguirre, H. D., & Palma-Cancino, D. J. (2026). Advances in Rice Agronomic Technologies in Latin America in the Face of Climate Change. Crops, 6(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/crops6010008