Native Cherimoya Trees with Commercial Potential from Southern Ecuador

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

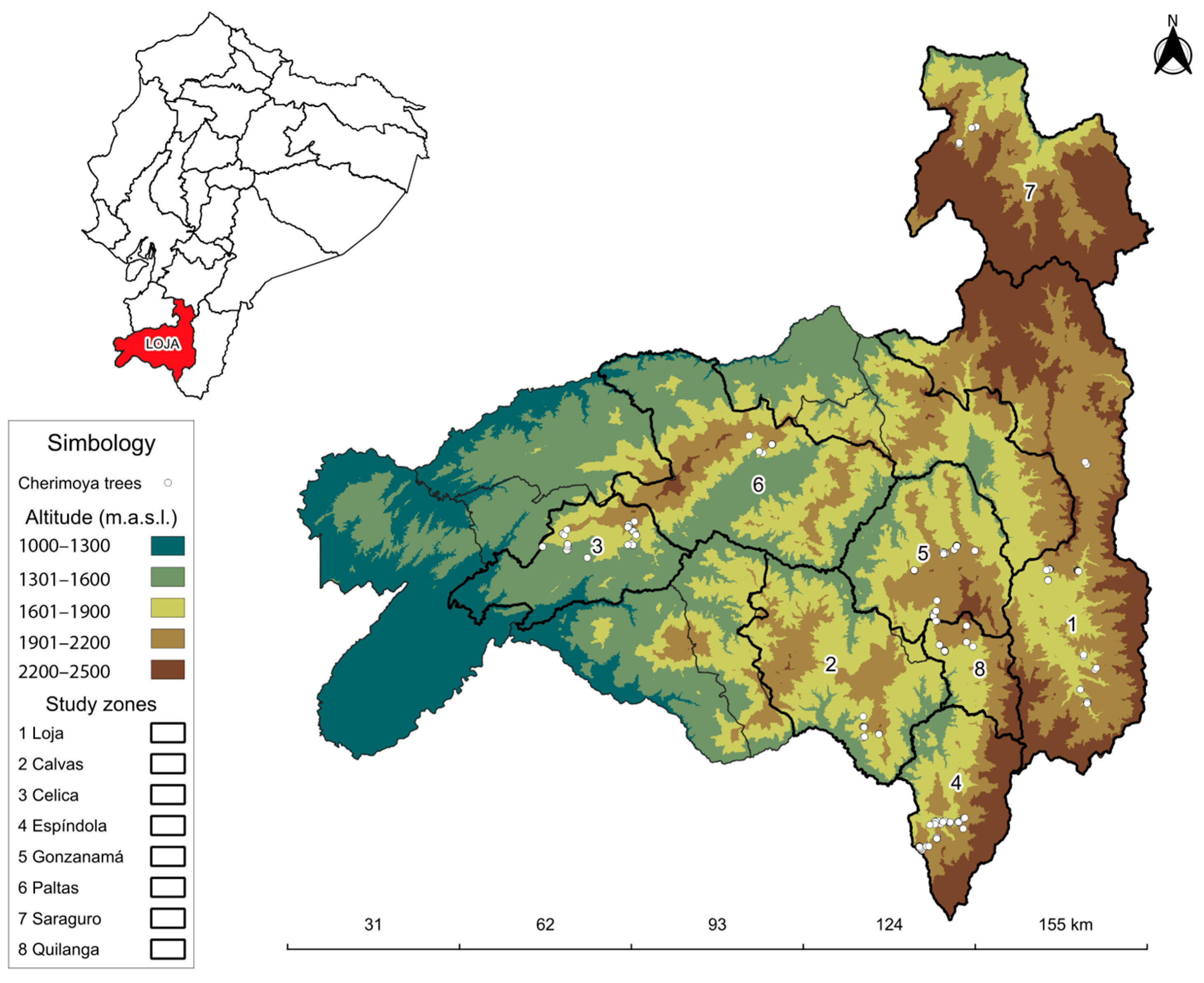

2.1. Experimental Conditions

2.2. Experimental Material

2.3. Quantitative and Qualitative Parameters

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Special Correlation Analysis Between Geographic and Phenotypic Distances (Mantel Test)

2.6. Multi-Character Selection Index Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Promissory Material Selection

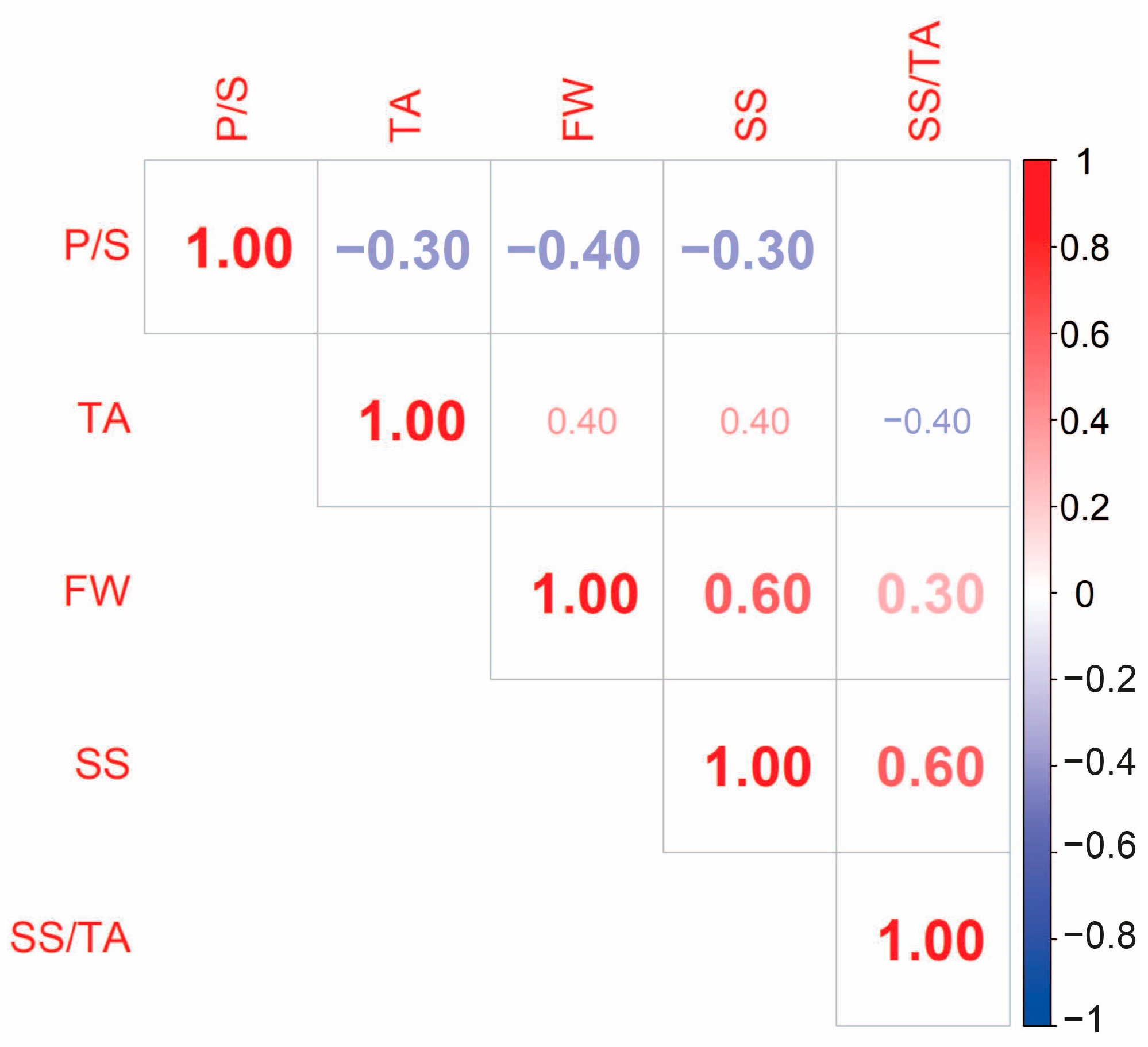

3.2. Correlations

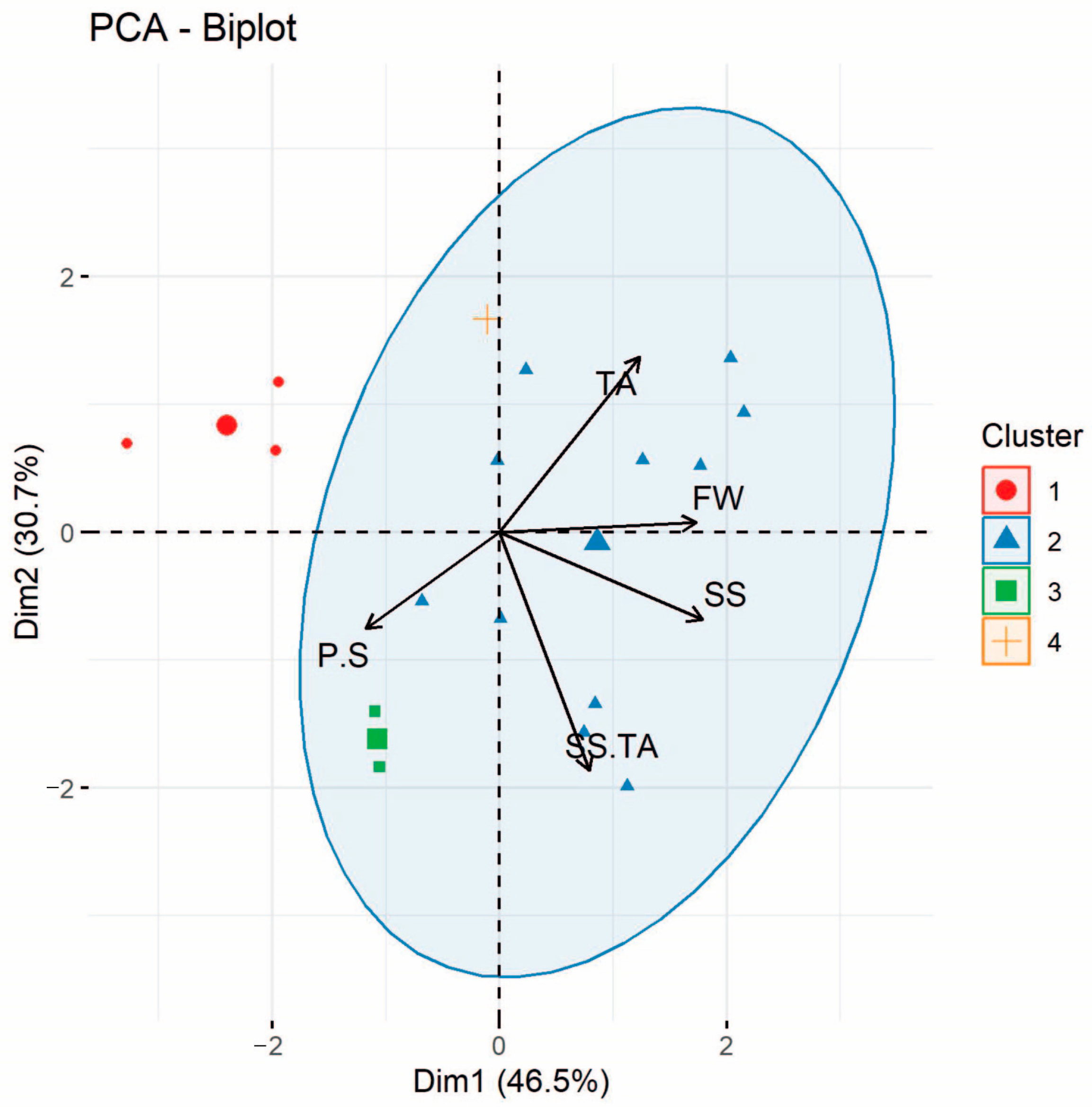

3.3. Principal Components Analysis (PCA)

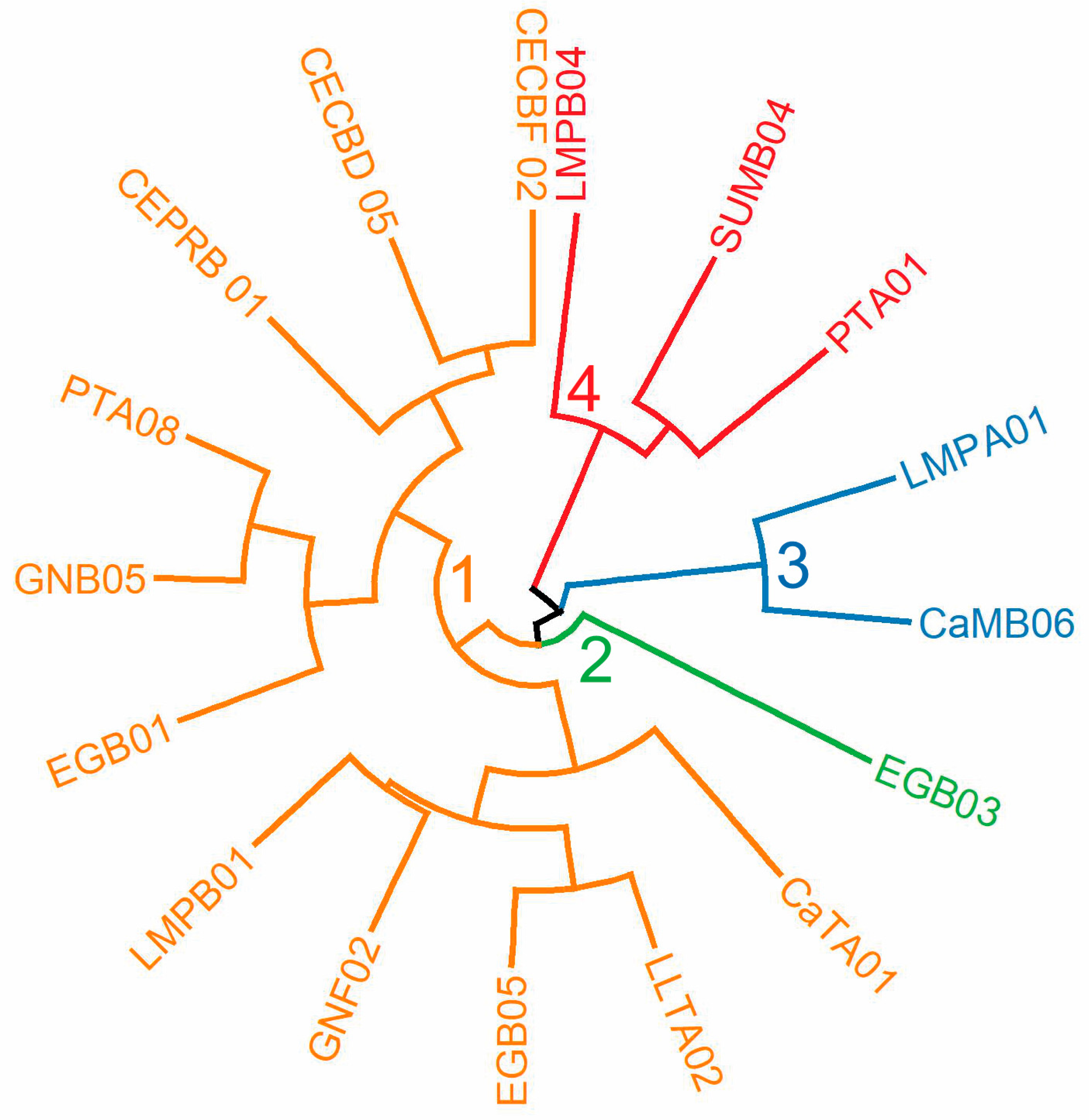

3.4. Hierarchical Clustering Analysis

3.5. Mantel Test

3.6. Multi-Character Selection Index

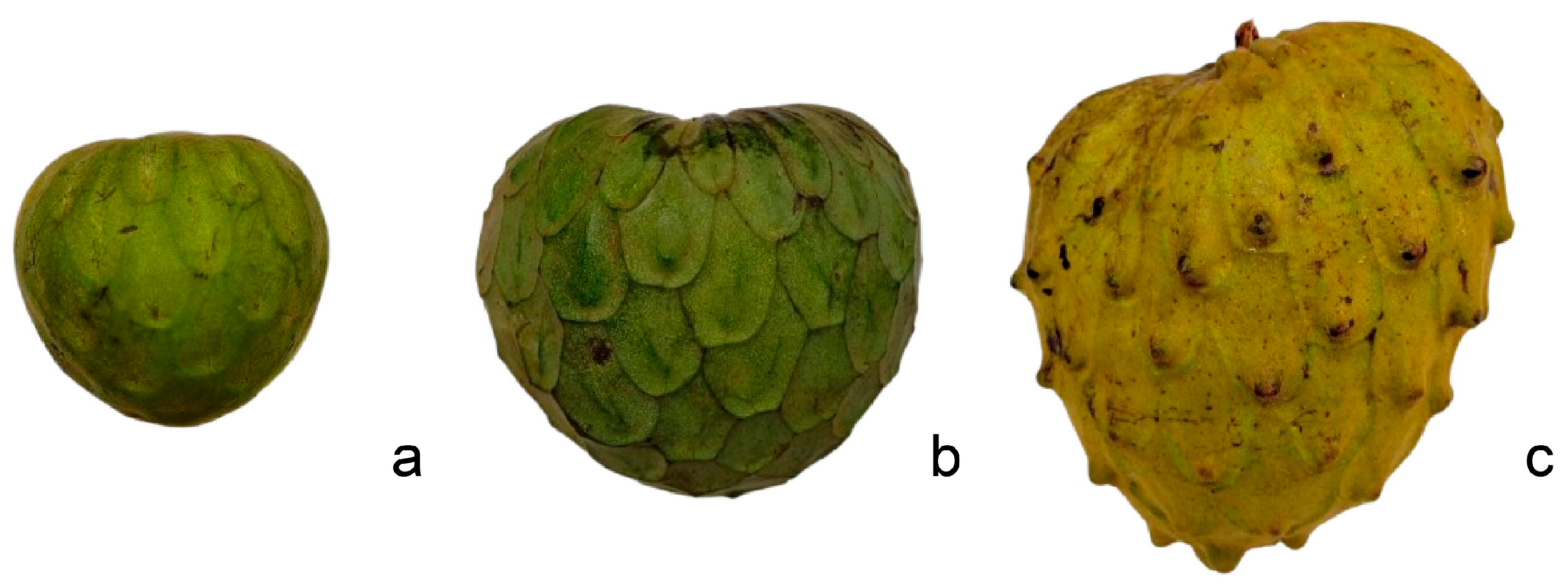

3.7. Fruit Variability

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van Zonneveld, M.; Scheldeman, X.; Escribano, P.; Viruel, M.A.; Van Damme, P.; Garcia, W.; Hormaza, J.I. Mapping Genetic Diversity of Cherimoya (Annona cherimola Mill.): Application of Spatial Analysis for Conservation and Use of Plant Genetic Resources. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Damme, P.; Scheldeman, X. Promoting Cultivation of Cherimoya in Latin America. Unasylva Engl. Ed. 1999, 50, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- González Vega, M.E. Chirimoya (Annona cherimola Miller), Frutal Tropical y Sub-Tropical de Valores Promisorios. Cultiv. Trop. 2013, 34, 52–63. [Google Scholar]

- Morales Astudillo, A.; Cueva Cueva, B.; Aquino Valarezo, P. Genetic Diversity and Geographic Distribution of Annona Cherimola in Southern Ecuador. Lyonia 2004, 7, 159–170. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, A.; Medina, A.; Criollo, L.; Castro, P. Resultados Interpretativos en la Herencia de Algunos Caracteres de Calidad en la Chirimoya (Annona cherimoola Mill.). Lyona 2006, 10, 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, R.; Moreno, J.; Buitrón, J.; Orbe, K.; Hector-Ardisana, E.; Uguña, F.; Viera, W. Characterization of Soursop Population (Annona muricata) from the Central Region of Ecuadorian Littoral Using ISSR Markers. Vegetos 2018, 31, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira-Macías, R.; Rodríguez, H.; Ardisana Eduardo, H.; Feicán-Mejía, C.; Mestanza Velasco, S.A.; Viera Arroyo, W. In Situ Morphological Characterization of Soursop (Annona muricata L.) Plants in Manabí, Ecuador. Enfoque UTE 2020, 11, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheldeman, X.; Ureña A, J.; Van Damme, V.; Van Damme, P. Potential of Cherimoya (Annona cherimola Mill.) in Southern Ecuador. Lyonia 2003, 5, 81–90. Available online: https://www.lyonia.org/Archives/Lyonia%205(1)%202003(1-100)/Scheldeman%2C%20X.%2C%20J.V.%20Ure%C3%B1a%20Alvarez%2C%20V.%20Van%20Damme%20%26%20P.%20Van%20Dam%3B%20Lyonia%205%281%29%202003%2881-90%29.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Vanhove, W.; Van Damme, P. Value Chains of Cherimoya (Annona cherimola Mill.) in a Centre of Diversity and Its on-Farm Conservation Implications. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2013, 6, 158–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano, P.; Viruel, M.A.; Hormaza, J.I. Molecular Analysis of Genetic Diversity and Geographic Origin within an Ex Situ Germplasm Collection of Cherimoya by Using SSRs. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2007, 132, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larranaga, N.; Agustín, J.A.; Albertazzi, F.; Fontecha, G.; Vásquez-Castillo, W.; Cautín, R.; Quiroz, E.; Ragonezi, C.; Hormaza, J.I. Underutilized Fruit Crops at a Crossroads: The Case of Annona Cherimola—From Pre-Columbian to Present Times. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheldeman, X.; Van Damme, P.; Urena Alvarez, J.V.; Romero Motoche, J.P. Horticultural Potential of Andean Fruit Crops Exploring Their Centre of Origin. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Sustainable Use of Plant Biodiversity to Promote New Opportunities for Horticultural Production, Antalya, Turkey, 6–9 November 2001; pp. 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, G.R.; Hartge, K. Bulk Density. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 1 Physical and Mineralogical Methods; American Society of Agronomy, Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 1986; Volume 5, pp. 363–375. [Google Scholar]

- Bouyoucos, G.J. Hydrometer Method Improved for Making Particle Size Analyses of Soils 1. Agron. J. 1962, 54, 464–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.W. Soil pH and Soil Acidity. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 3 Chemical Methods; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; Volume 5, pp. 475–490. [Google Scholar]

- Walkley, A.; Black, I.A. An Examination of the Degtjareff Method for Determining Soil Organic Matter, and a Proposed Modification of the Chromic Acid Titration Method. Soil Sci. 1934, 37, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, M.E.; Miller, W.P. Cation Exchange Capacity and Exchange Coefficients. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 3 Chemical Methods; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; Volume 5, pp. 1201–1229. [Google Scholar]

- Bremner, J.M. Nitrogen-total. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 3 Chemical Methods; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; Volume 5, pp. 1085–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, S.R. Estimation of Available Phosphorus in Soils by Extraction with Sodium Bicarbonate; US Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, L.A. Diagnosis and Improvement of Saline and Alkali Soils; US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, D.; Page, A.; Helmke, P.; Loeppert, R.; Soltanpour, P.; Tabatabai, M.; Johnston, C.; Sumner, M. Methods of Soil Analysis; SSSA Book Series; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; Volume 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, W.L.; Norvell, W. Development of a DTPA Soil Test for Zinc, Iron, Manganese, and Copper. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1978, 42, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés-Agustín, J.; González-Andrés, F.; Nieto-Ángel, R.; Barrientos-Priego, A. Morphometry of the Organs of Cherimoya (Annona cherimola Mill.) and Analysis of Fruit Parameters for the Characterization of Cultivars, and Mexican Germplasm Selections. Sci. Hortic. 2006, 107, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozowara, X.; Whitehead, S.R. Variability in Apple Fruit Quality across Management Systems and Latitudinal Climate Gradients. Plants People Planet 2025, 8, 212–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Mendoza, C.F.; Ortegón-Campos, I.; Marrufo-Zapata, D.; Herrera, C.M.; Parra-Tabla, V. Genetic Diversity, Outcrossing Rate, and Demographic History along a Climatic Gradient in the Ruderal Plant Ruellia Nudiflora (Acanthaceae). Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2015, 86, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- [BLM] Bureau of Land Management. Technical Protocol for the Collection, Study, and Conservation of Seeds from Native Plant Species for Seeds of Success; Bureau of Land Management: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gentile, C.; Mannino, G.; Palazzolo, E.; Gianguzzi, G.; Perrone, A.; Serio, G.; Farina, V. Pomological, Sensorial, Nutritional and Nutraceutical Profile of Seven Cultivars of Cherimoya (Annona cherimola Mill.). Foods 2020, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oñate-Valdivieso, F.; Fries, A.; Mendoza, K.; Gonzalez-Jaramillo, V.; Pucha-Cofrep, F.; Rollenbeck, R.; Bendix, J. Temporal and Spatial Analysis of Precipitation Patterns in an Andean Region of Southern Ecuador Using LAWR Weather Radar. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 2018, 130, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biodiversity International; CHERLA. Descriptores Para Chirimoyo (Annona cherimola Mill.); Bioversity International: Rome, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pariona, F.G.; Maldonado, A.C.Y. Identificación In Situ de Ecotipos de Chirimoya (Annona cherimola Mill.) con Aptitudes Potencialmente Comerciales en el Distrito de Churubamba–Huánuco. Investig. Valdizana 2014, 8, 09–17. [Google Scholar]

- INIAP. Aplicación de Tecnologías Agroindustriales Para El Tratamiento de La Chirimoya Con Fines de Exportación; INIAP-Estación Experimental Santa Catalina: Quito, Ecuador, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Scheldeman, X. Distribution and Potential of Cherimoya (Annona cherimola Mill.) and Highland Papayas (Vasconcellea spp.) in Ecuador. Ph.D. Thesis, University Gent, Gent, Belgium, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, G.; Serrano, M.; Pretel, M.T.; Riquelme, F.; Rojomaro, F. Ethylene Biosynthesis and Physico-Chemical Changes during Fruit Ripening of Cherimoya (Annona cherimola Mill.). J. Hortic. Sci. 1993, 68, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posit Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. 2025. Available online: http://www.posit.co/ (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’hara, R.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. 2001. Available online: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1370564064030507943 (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Hijmans, R.J.; Williams, E.; Vennes, C. Geosphere: Spherical Trigonometry, R package version 1.5-10; Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN): Vienna, Austria, 2019.

- Wickham, H.; Bryan, J. Readxl: Read Excel Fileshttps. Readxl. Tidyverse. Org. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/tidyverse/readxl (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Wickham, H.; François, R.; Henry, L.; Müller, K.; Vaughan, D. Dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation, Version 1.1.4; Posit Software: Boston, MA, USA, 2023.

- Van Damme, P.; Van Damme, V.; Scheldeman, X. Ecology and Cropping of Cherimoya (Annona cherimola Mill.) in Latin America. New Data from Ecuador. Fruits 2000, 55, 195–206. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, I.K.; Lengkeek, A.; Weber, J.C.; Jamnadass, R. Managing Genetic Variation in Tropical Trees: Linking Knowledge with Action in Agroforestry Ecosystems for Improved Conservation and Enhanced Livelihoods. Biodivers. Conserv. 2009, 18, 969–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kome, G.K.; Enang, R.K.; Silatsa, F.B.; Yerima, B.P.; Van Ranst, E. Baseline Edaphic Requirements of Soursop (Annona muricata L.). Trop. Plants 2024, 3, e022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donhouedé, J.C.; Salako, K.V.; Assogbadjo, A.E.; Ribeiro-Barros, A.I.; Ribeiro, N. The Relative Role of Soil, Climate, and Genotype in the Variation of Nutritional Value of Annona Senegalensis Fruits and Leaves. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, T.; Hidalgo, R. Análisis Estadísitico de Datos de Caracterización Morfológica de Recursos Fitogenéticos; IPGRI: Roma, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fos, M.; Nuez, F.; García-Martínez, J.L. The Gene Pat-2, Which Induces Natural Parthenocarpy, Alters the Gibberellin Content in Unpollinated Tomato Ovaries. Plant Physiol. 2000, 122, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercati, F.; Longo, C.; Poma, D.; Araniti, F.; Lupini, A.; Mammano, M.M. Genetic Variation of an Italian Long Shelf-Life Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Collection by Using SSR and Morphological Fruit Traits. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2014, 62, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figàs, M.R.; Prohens, J.; Raigón María, D.; Fernàndez de Córdova, P.; Fita, A.; Soler, S. Characterization of a Collection of Local Varieties of Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Using Conventional Descriptors and the High-Throughput Phenomics Tool Tomato Analyzer. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2015, 62, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nankar, A.N.; Tringovska, I.; Grozeva, S.; Ganeva, D.; Kostova, D. Tomato Phenotypic Diversity Determined by Combined Approaches of Conventional and High-Throughput Tomato Analyzer Phenotyping. Plants 2020, 9, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, G.S. Evaluación Morfológica y Molecular de Accesiones de Anonáceas (Anón, Chirimoya y Atemoya) en Condiciones in situ, de las Regiones Andina y Caribe Colombiano. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Crisosto, C.H.; Crisosto, G.; Bowerman, E. Understanding Consumer Acceptance of Peach, Nectarine and Plum Cultivars. In International Conference on Quality in Chains. An Integrated View on Fruit and Vegetable Quality; International Society for Horticultural Science: Leuven, Belgium, 2003; Volume 604, pp. 115–119. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, S.K. Postharvest Physiology and Storage of Tropical and Subtropical Fruits; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Palma, T.; Aguilera, J.M.; Stanley, D.W. A Review of Postharvest Events in Cherimoya. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 1993, 2, 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheldeman, X.; Van Damme, P. Promising Cherimoya (Annona cherimola Mill.) Accessions in Loja Province, Southern Ecuador. In Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Cherimoya, Loja, Ecuador, 16–19 March 1999; pp. 173–188. [Google Scholar]

- Scheldeman, X.; Ureña, V.; Van Damme, P. Collection and Characterisation of Cherimoya (Annona cherimola Mill.) in Loja Province, Southern Ecuador. In Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Cherimoya, Loja, Ecuador, 16–19 March 1999; pp. 153–172. [Google Scholar]

- Scheldeman, X.; Van Damme, P.; Motoche, J.R.; Alvarez, J.U. Germplasm Collection and Fruit Characterisation of Cherimoya (Annona cherimola) in Loja Province, Ecuador, an Important Centre of Biodiversity. Belg. J. Bot. 2006, 139, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Motamayor, J.C.; Lachenaud, P.; Da Silva e Mota, J.W.; Loor, R.; Kuhn, D.N.; Brown, J.S.; Schnell, R.J. Geographic and Genetic Population Differentiation of the Amazonian Chocolate Tree (Theobroma cacao L.). PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavez, R.; Loreto, M. Response to Artificial Pollination and Determination of Physical and Chemical Changes of Cherimoya Fruit (Annona cherimola Mill.) in Different Cultivars Grown in La Cruz. 1985. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14001/63815 (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Tietz, J.M. Relación Entre Pilosidad Del Fruto de Chirimoyo (A. cherirnola Mill.) y Evoluci6n de Madurez. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Valparaiso, Chile, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Alique, R.; Zamorano, J.P. Influence of Harvest Date within the Season and Cold Storage on Cherimoya Fruit Ripening. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 4209–4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, C. Pollination of Cherimoyas California. Calif. Avocado Soc. Yearb. 1995, 44, 119–122. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, I.K.; Vincenti, B.; Weber, J.C.; Neufeldt, H.; Russell, J. Climate Change and Tree Genetic Resource Management: Maintaining and Enhancing the Productivity and Value of Smallholder Tropical Agroforestry Landscapes. A Review. Agrofor. Syst. 2011, 81, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmberg-Lerche, C. Thoughts on the Conservation of Forest Biological Diversity and Forest Tree and Shrub Genetic Resources. J. Trop. For. Sci. 2008, 20, 300–312. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Range (Study Area) | Method |

|---|---|---|

| Bulk density (g/cm3) | 1.0–1.4 | Cylinder method [13] |

| Soil texture | Loam to clay loam (predominant) | Bouyoucos hydrometer method [14] |

| pH | 5.5–6.5 | Electrometry in soil-water suspension (1:2.5 or 1:1) [15]. |

| Organic matter (%) | 3.0–4.5 | Walkley–Black wet oxidation [16] |

| Cation exchange capacity (meq/100 g) | 19–23 | Ammonium acetate pH 7 [17] |

| Nitrogen (%) | 0.22–0.33 | Kjeldahl digestion [18] |

| Phosphorus (mg/kg) | 6.4–94.6 | Olsen method (NaHCO3 0.5 M, pH 8.5) [19] |

| Potassium (mg/kg) | 234–491 | Extraction with ammonium acetate (1N, pH 7) and AAS reading [20] |

| Magnesium (mg/kg) | 216–632 | 1N ammonium acetate + AAS spectrophotometry [21] |

| Calcium (mg/kg) | 1367–4011 | Ammonium acetate 1N + AAS [21] |

| Iron (mg/kg) | 59–271 | Extraction with DTPA/EDTA (Lindsay & Norvell) + AAS [22] |

| Copper (mg/kg) | 0.5–8.5 | DTPA-EDTA (Lindsay y Norvell) + AAS [22] |

| Manganese (mg/kg) | 14–73 | DTPA-EDTA + AAS [22] |

| Descriptor | Determination Method |

|---|---|

| Pulp/Seed ratio (PS) | Division of the weight of pulp over total weight of all fresh seeds per fruit. |

| Titratable acidity (% of citric acid per 100 g of pulp) (TA) | Citric acid content per 100 g of pulp determined by the AOAC method (942.15). |

| Soluble solids (°Brix) (SS) | Average sugar value for 5 representative fruits determined using a HI-96800 digital refractometer (Hanna Instruments, Woonsocket, RI, USA). |

| Fruit weight (g) (FW) | Weight of the mature fruit without its peduncle. |

| Acidity ratio (SSTA) | Relationship between total soluble solids (TSS, expressed in °Brix) and titratable acidity (TA, expressed as % citric acid). |

| Variables | Max | Min | Mean | SD | CV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pulp/Seed ratio | 23.49 | 10.22 | 14.64 | 4.32 | 29.48 |

| Titratable acidity (meq/100 g) | 0.48 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.05 | 12.82 |

| Soluble solids (°Brix) | 27.65 | 16.10 | 22.54 | 3.34 | 14.83 |

| Fruit weight (g) | 492.80 | 236.00 | 392.00 | 80.26 | 20.47 |

| Soluble solids/Titratable acidity ratio | 74.71 | 44.86 | 58.23 | 9.03 | 15.51 |

| Traits | PC1 | PC2 |

|---|---|---|

| Pulp/Seed relation | 0.33 | 0.21 |

| Titratable acidity (meq/100 g) | 0.24 | 0.45 |

| Soluble solids (°Brix) | 0.24 | 0.05 |

| Fruit weight (g) | 0.13 | 0.00 |

| Soluble solids/Titratable acidity relation | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Variability (%) | 46.54 | 30.70 |

| Cluster | Pulp/Seed Relation | Titratable Acidity (%) | Soluble Solids (°Brix) | Fruit Weight (g) | Soluble Solids/Titratable Acidity Relation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15.70 | 0.35 | 17.10 | 274.00 | 47.70 |

| 2 | 12.50 | 0.39 | 24.00 | 432.00 | 60.90 |

| 3 | 22.70 | 0.36 | 23.70 | 312.00 | 65.90 |

| 4 | 18.90 | 0.45 | 20.30 | 471.00 | 44.90 |

| ID | Index | FW | P/S | SS | TA | SS/TA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EACAD01 | 1.77 | −0.16 | 2.35 | −0.30 | −0.08 | −0.05 |

| LYHA01 | 1.60 | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.19 | −0.28 | 1.73 |

| CECBA 02 | 1.56 | −0.20 | 2.09 | −0.24 | 0.02 | −0.10 |

| LYHB04 | 1.08 | −0.13 | 1.30 | −0.11 | 0.16 | −0.14 |

| GNA07 | 1.03 | −0.19 | 1.21 | −0.16 | 0.35 | −0.20 |

| CaMUA04 | 0.89 | −0.17 | 0.72 | 0.29 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Capa-Morocho, M.; Granja, F.; Molina-Müller, M.; Vásquez, S.C.; Erazo-Hurtado, S.; Vaca, A.; Pineda-Escobar, M.O.; Rogel, G.; Romero, M.A.; Chamba-Zaragocin, D. Native Cherimoya Trees with Commercial Potential from Southern Ecuador. Crops 2026, 6, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/crops6010007

Capa-Morocho M, Granja F, Molina-Müller M, Vásquez SC, Erazo-Hurtado S, Vaca A, Pineda-Escobar MO, Rogel G, Romero MA, Chamba-Zaragocin D. Native Cherimoya Trees with Commercial Potential from Southern Ecuador. Crops. 2026; 6(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/crops6010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleCapa-Morocho, Mirian, Fernando Granja, Marlene Molina-Müller, Santiago C. Vásquez, Santiago Erazo-Hurtado, Alejandro Vaca, Marlon Oswaldo Pineda-Escobar, Guillermo Rogel, Melissa A. Romero, and Diego Chamba-Zaragocin. 2026. "Native Cherimoya Trees with Commercial Potential from Southern Ecuador" Crops 6, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/crops6010007

APA StyleCapa-Morocho, M., Granja, F., Molina-Müller, M., Vásquez, S. C., Erazo-Hurtado, S., Vaca, A., Pineda-Escobar, M. O., Rogel, G., Romero, M. A., & Chamba-Zaragocin, D. (2026). Native Cherimoya Trees with Commercial Potential from Southern Ecuador. Crops, 6(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/crops6010007