Comparative Assessment of Verticillium dahliae Tolerance in 77 Olive Cultivars

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Selection and Preparation of Plant Materials

2.2. Phatogen Inoculum Preparation

2.3. Plant Inoculation Procedure

2.4. Disease Severity Assessment

2.5. Molecular Detection of V. dahliae in Infected Plantlets

2.6. Statistical Analysis

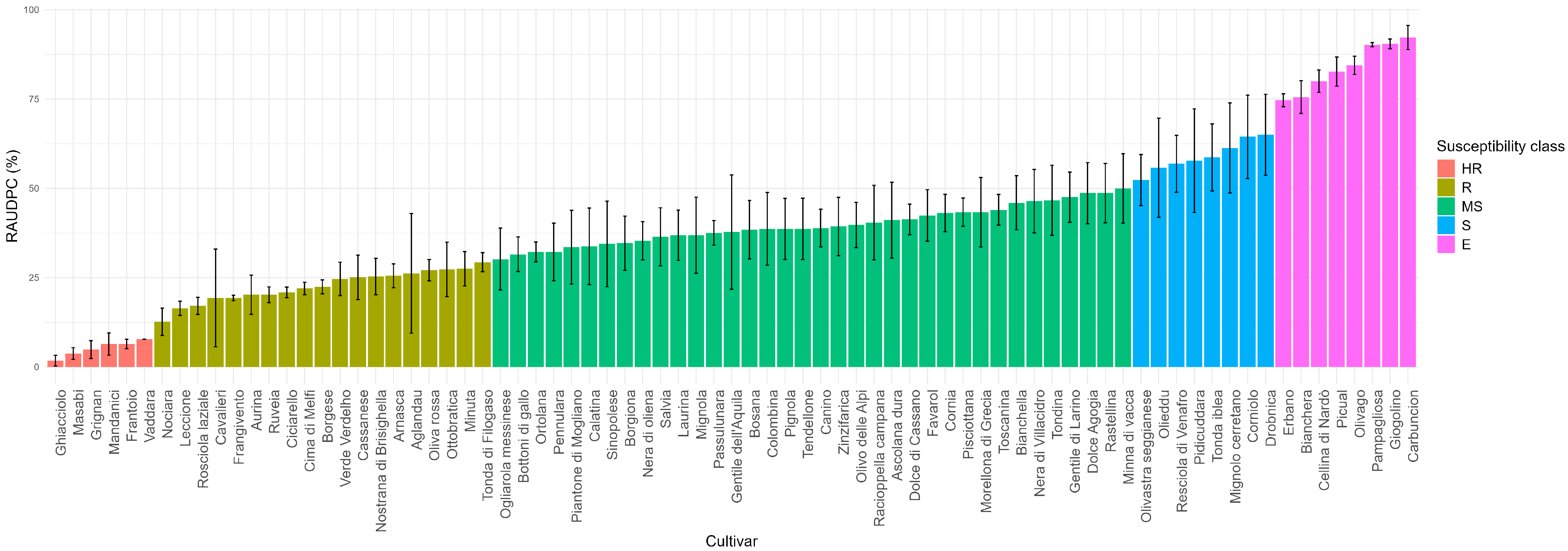

3. Results

3.1. Parameter Analysis

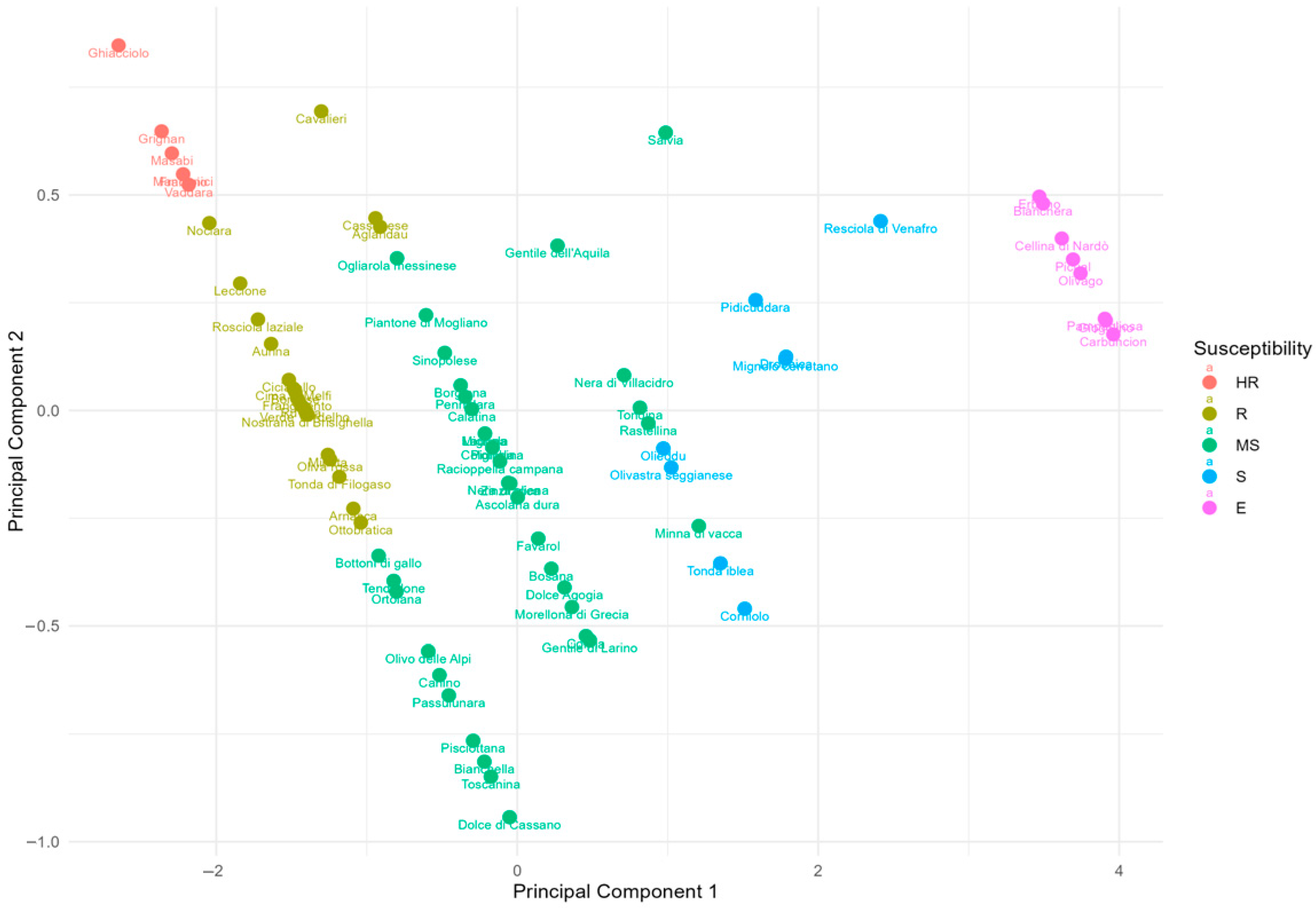

3.2. Principal Component Analysis

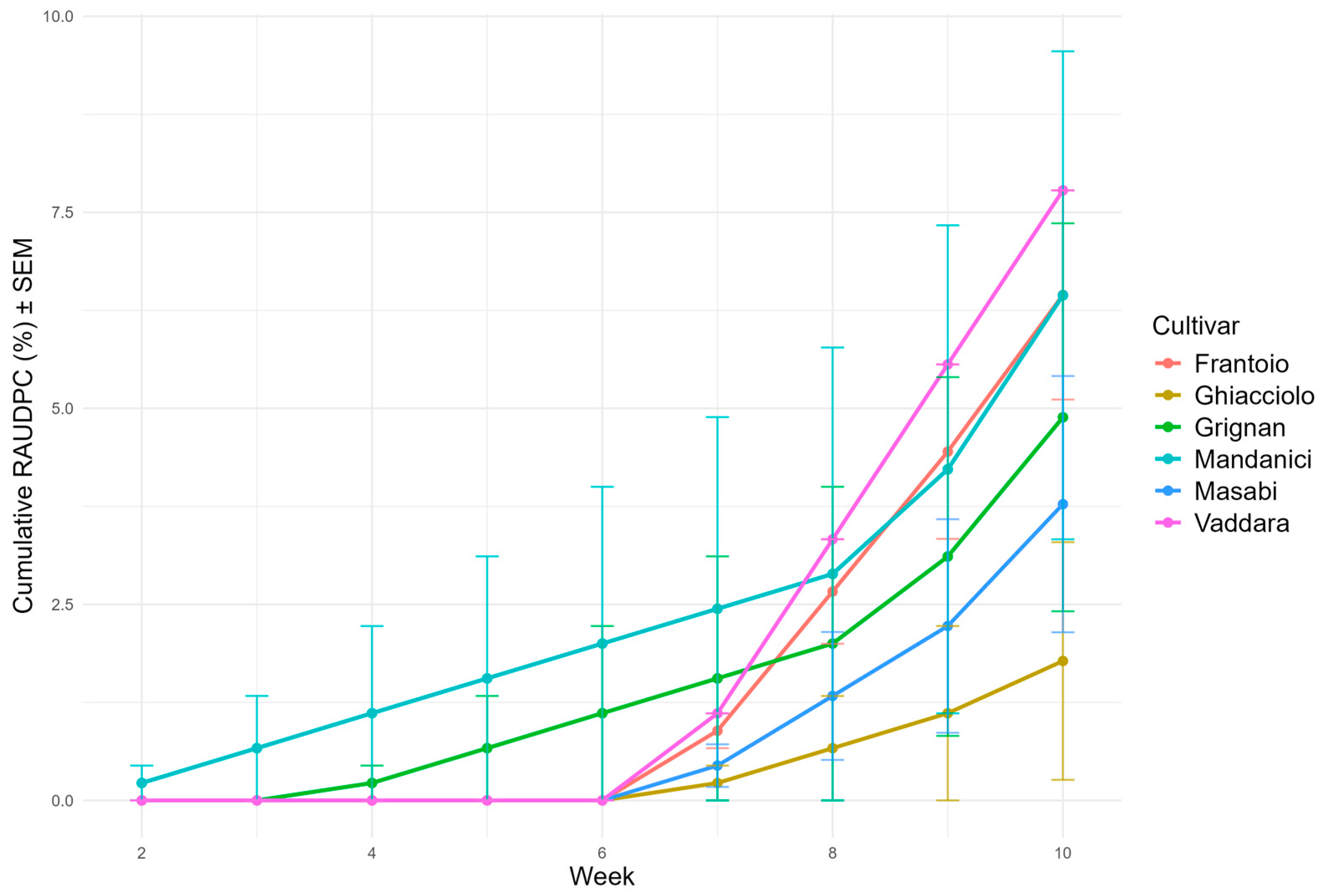

3.3. Highly Resistant Class (HR)

3.4. Resistant Class (R)

3.5. Moderately Susceptible Class (MS)

3.6. Susceptible Class (S)

3.7. Extremely Susceptible Class (E)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jiménez-Díaz, R.M.; Cirulli, M.; Bubici, G.; del Mar Jiménez-Gasco, M.; Antoniou, P.P.; Tjamos, E.C. Verticillium Wilt, A Major Threat to Olive Production: Current Status and Future Prospects for Its Management. Plant Dis. 2012, 96, 304–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Escudero, F.J.; Mercado-Blanco, J. Verticillium Wilt of Olive: A Case Study to Implement an Integrated Strategy to Control a Soil-Borne Pathogen. Plant Soil. 2011, 344, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, L.; Farolfi, C.; Tombesi, S.; Novelli, E.; Capri, E. Development of a sustainability technical guide for the Italian olive oil supply chain. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 820, 153332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes-Osuna, N.; Mercado-Blanco, J. Verticillium Wilt of Olive and Its Control: What Did We Learn during the Last Decade? Plants 2020, 9, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragüés, R.; Guillén, M.; Royo, A. Five-Year Growth and Yield Response of Two Young Olive Cultivars (Olea europaea L., Cvs. Arbequina and Empeltre) to Soil Salinity. Plant Soil 2010, 334, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landa, B.B.; Pérez, A.G.; Luaces, P.; Montes-Borrego, M.; Navas-Cortés, J.A.; Sanz, C. Insights Into the Effect of Verticillium dahliae Defoliating-Pathotype Infection on the Content of Phenolic and Volatile Compounds Related to the Sensory Properties of Virgin Olive Oil. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurado, D.R.; López, M.A.B.; Rapoport, H.F.; Diaz, R.M.J. Present Status of Verticillium Wilt of Olive in Andalucía (Southern Spain)1. EPPO Bull. 1993, 23, 513–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-López, M.A.; Jiménez-Díaz, R.M.; Caballero, J.M. Symptomatology, Incidence and Distribution of Verticillium Wilt of Olive Trees in Andalucía. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 1984, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Escudero, F.J.; Blanco-Lopez, M.A. Effect of a Single or Double Soil Solarization to Control Verticillium Wilt in Established Olive Orchards in Spain. Plant Dis. 2001, 85, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keykhasaber, M.; Thomma, B.P.H.J.; Hiemstra, J.A. Verticillium Wilt Caused by Verticillium dahliae in Woody Plants with Emphasis on Olive and Shade Trees. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2018, 150, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegg, G.F.; Brady, B.L. Verticillium Wilts; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- El-Zik, K.M. Integrated Control of Verticillium Wilt of Cotton. Plant Dis. 1985, 69, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fradin, E.F.; Thomma, B.P.H.J. Physiology and Molecular Aspects of Verticillium Wilt Diseases Caused by V. dahliae and V. albo-atrum. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2006, 7, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klosterman, S.J.; Atallah, Z.K.; Vallad, G.E.; Subbarao, K.V. Diversity, Pathogenicity, and Management of Verticillium Species. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2009, 47, 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Báidez, A.G.; Gómez, P.; Del Río, J.A.; Ortuño, A. Dysfunctionality of the Xylem in Olea europaea L. Plants Associated with the Infection Process by Verticillium dahliae Kleb. Role of Phenolic Compounds in Plant Defense Mechanism. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 3373–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiemstra, J.A. A Compendium of Verticillium Wilts in Tree Species; Ponsen & Looijen, the Commission of the European Communities: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1998; ISBN 978-90-73771-25-3. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoni, M.; Gómez-Lama Cabanás, C.; Valverde-Corredor, A.; Villar, R.; Mercado-Blanco, J. Unveiling Differences in Root Defense Mechanisms Between Tolerant and Susceptible Olive Cultivars to Verticillium dahliae. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 863055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Escudero, F.J.; del Río, C.; Caballero, J.M.; Blanco-López, M.A. Evaluation of Olive Cultivars for Resistance to Verticillium dahliae. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2004, 110, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado-Blanco, J.M.; Collado-Romero, M.; Rodríguez-Jurado, D.; Jiménez-Díaz, R.M. Aplicación de Técnicas Moleculares Para Determinar La Incidencia y Extensión de La Colonización de Plantas de Olivo Por Los Patotipos de Verticillium dahliae. Olivae Rev. Of. Cons. Oleíc. Int. 2005, 104, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Valverde, P.; Trapero, C.; Arquero, O.; Serrano, N.; Barranco, D.; Muñoz Díez, C.; López-Escudero, F.J. Highly Infested Soils Undermine the Use of Resistant Olive Rootstocks as a Control Method of Verticillium Wilt. Plant Pathol. 2021, 70, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varo, A.; Moral, J.; Lozano-Tóvar, M.D.; Trapero, A. Development and Validation of an Inoculation Method to Assess the Efficacy of Biological Treatments against Verticillium Wilt in Olive Trees. BioControl 2016, 61, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Rueda, P.; Aguado, A.; Romero-Cuadrado, L.; Capote, N.; Colmenero-Flores, J.M. Wild Olive Genotypes as a Valuable Source of Resistance to Defoliating Verticillium dahliae. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 662060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado-Blanco, J.; Rodríguez-Jurado, D.; Parrilla-Araujo, S.; Jiménez-Díaz, R.M. Simultaneous Detection of the Defoliating and Nondefoliating Verticillium dahliae Pathotypes in Infected Olive Plants by Duplex, Nested Polymerase Chain Reaction. Plant Dis. 2003, 87, 1487–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keykhasaber, M.; Pham, K.T.K.; Thomma, B.P.H.J.; Hiemstra, J.A. Reliable Detection of Unevenly Distributed Verticillium dahliae in Diseased Olive Trees. Plant Pathol. 2017, 66, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcón-Piñeiro, A.; Zaguirre-Martínez, J.; Ibáñez-Hernández, A.C.; Guillamón, E.; Santander, K.; Barrero-Domínguez, B.; López-Feria, S.; Garrido, D.; Baños, A. Evaluation of the Biostimulant Activity and Verticillium Wilt Protection of an Onion Extract in Olive Crops (Olea europaea). Plants 2024, 13, 2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ruiz, G.M.; Trapero, C.; Varo-Suárez, Á.; Trapero, A.; López-Escudero, F.J. Identifying Resistance to Verticillium Wilt in Local Spanish Olive Cultivars. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2015, 54, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Escudero, F.J.; Mwanza, C.; Blanco-López, M.A. Reduction of Verticillium dahliae Microsclerotia Viability in Soil by Dried Plant Residues. Crop Prot. 2007, 26, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva-Pérez, M.D.L.O.; Jiménez-Ruiz, J.; Gómez-Lama Cabanás, C.; Valverde-Corredor, A.; Barroso, J.B.; Luque, F.; Mercado-Blanco, J. Tolerance of Olive (Olea europaea) Cv Frantoio to Verticillium dahliae Relies on Both Basal and Pathogen-induced Differential Transcriptomic Responses. New Phytol. 2018, 217, 671–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martos-Moreno, C.; López-Escudero, F.J.; Blanco-López, M.Á. Resistance of Olive Cultivars to the Defoliating Pathotype of Verticillium dahliae. HortScience 2006, 41, 1313–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapero, C.; Rallo, L.; López-Escudero, F.J.; Barranco, D.; Díez, C.M. Variability and Selection of Verticillium Wilt Resistant Genotypes in Cultivated Olive and in the Olea Genus. Plant Pathol. 2015, 64, 890–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalisi, A.; Marino, G.; Marra, F.P.; Caruso, T.; Lo Bianco, R. A Cultivar-Sensitive Approach for the Continuous Monitoring of Olive (Olea europaea L.) Tree Water Status by Fruit and Leaf Sensing. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, G.; Marrazzo, M.T.; Marconi, R.; Cimato, A.; Testolin, R. Microsatellite Markers Isolated in Olive (Olea europaea L.) Are Suitable for Individual Fingerprinting and Reveal Polymorphism within Ancient Cultivars. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2002, 104, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmmam, I.; Mariotti, R.; Ruperti, B.; Cultrera, N.; Baldoni, L.; Barcaccia, G. Venetian Olive (Olea europaea) Germplasm: Disclosing the Genetic Identity of Locally Grown Cultivars Suited for Typical Extra Virgin Oil Productions. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2018, 65, 1733–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotondi, A.; Magli, M.; Ricciolini, C.; Baldoni, L. Morphological and Molecular Analyses for the Characterization of a Group of Italian Olive Cultivars. Euphytica 2003, 132, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilušić, T.; Žanetić, M.; Ljubenkov, I.; Generalić Mekinić, I.; Štambuk, S.; Bojović, V.; Soldo, B.; Magiatis, P. Molecular Characterization of Dalmatian Cultivars and the Influence of the Olive Fruit Harvest Period on Chemical Profile, Sensory Characteristics and Oil Oxidative Stability. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2018, 244, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Rufo, A.; Molina-Molina, M.; Alcántara-Vara, E.; Weiland-Ardáiz, C.; López-Escudero, F.J. Vessel Anatomical Features of ‘Picual’ and ‘Frantoio’, Two Olive Cultivars Different in Resistance against Verticillium Wilt of Olive. Plants 2023, 12, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colzi, I.; Marone, E.; Luti, S.; Pazzagli, L.; Mancuso, S.; Taiti, C. Metabolic Responses in Leaves of 15 Italian Olive Cultivars in Correspondence to Variable Climatic Elements. Plants 2023, 12, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbi, Y.; Barkallah, M.; Bouazizi, E.; Hibar, K.; Gdoura, R.; Triki, M.A. Lignification, Phenols Accumulation, Induction of PR Proteins and Antioxidant-Related Enzymes Are Key Factors in the Resistance of Olea europaea to Verticillium Wilt of Olive. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2017, 39, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbi, Y.; Barkallah, M.; Bouazizi, E.; Cheffi, M.; Gdoura, R.; Triki, M.A. Differential Fungal Colonization and Physiological Defense Responses of New Olive Cultivars Infected by the Necrotrophic Fungus Verticillium dahliae. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2016, 38, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Tejero, J.A.; Jiménez-Ruiz, J.; Serrano, A.; Belaj, A.; León, L.; De La Rosa, R.; Mercado-Blanco, J.; Luque, F. Verticillium Wilt Resistant and Susceptible Olive Cultivars Express a Very Different Basal Set of Genes in Roots. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, E. La Toscana Nella Storia Dell’olivo e Dell’olio; ARSIA: Perugia, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rotondi, A. L’attitudine Alla Propagazione e la Certificazione Genetica e Sanitaria Dell’olivo in Emilia-Romagna; Regione Emilia-Romagna: Bologna, Italy; Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche: Roma, Italy, 2004; ISBN 978-88-900593-3-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarese, F.; Ambrico, A.; Longo, O.; Schiavone, D. Search for Resistance to Verticillium-Wilt and Leaf Spot in Olive. Acta Hortic. 2002, 586, 717–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulè, R.; Fodale, A.S.; Tucci, A. Selezione Varietale Dell’olivo Nella Sicilia Sud-Occidentale: Caratterizzazione di ‘Tunnulidda’, ‘Cacaridduni’, Zarbo’ e ‘Bottini di Gallo Vassallo’, Quattro Entità Minori del Germoplasma Olivicolo Siciliano. Convegno “Germoplasma Olivicolo e Tipicità Dell’olio”; SOI, Univ. Perugia, Dip. Arboricoltura e Protezione Piante: Perugia, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cirulli, M.; Montemurro, G. A Comparison of Pathogenic Isolates of Verticillium dahliae and Sources of Resistance in Olive. Poljopr. Znan. Smotra 1976, 39, 469–476. [Google Scholar]

| Cultivar | Origin | Cultivar | Origin | Cultivar | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gentile dell’Aquila | Abruzzo | Colombina | Emilia-Romagna | Ogliarola messinese | Sicily |

| Nociara | Apulia | Ghiacciolo | Emilia-Romagna | Bottoni di gallo | Sicily |

| Frangivento | Apulia | Carbuncion | Emilia-Romagna | Calatina | Sicily |

| Oliva rossa | Apulia | Bianchera | Friuli Venezia-Giulia | Passulunara | Sicily |

| Rastellina | Apulia | Rosciola laziale | Lazio | Bianchella | Sicily |

| Cellina di Nardò | Apulia | Salvia | Lazio | Minna di vacca | Sicily |

| Cima di Melfi | Basilicata | Canino | Lazio | Mandanici | Sicily |

| Ciciarello | Calabria | Morellona di Grecia | Lazio | Vaddara | Sicily |

| Borgese | Calabria | Arnasca | Liguria | Erbano | Sicily |

| Cassanese | Calabria | Pignola | Liguria | Olivastra seggianese | Tuscany |

| Ottobratica | Calabria | Olivo delle Alpi | Liguria | Mignolo cerretano | Tuscany |

| Tonda di Filogaso | Calabria | Piantone di Mogliano | Marche | Leccione | Tuscany |

| Pennulara | Calabria | Laurina | Marche | Toscanina | Tuscany |

| Sinopolese | Calabria | Mignola | Marche | Frantoio | Tuscany |

| Zinzifarica | Calabria | Ascolana dura | Marche | Giogolino | Tuscany |

| Dolce di Cassano | Calabria | Resciola di Venafro | Molise | Borgiona | Umbria |

| Tondina | Calabria | Aurina | Molise | Tendellone | Umbria |

| Olivago | Calabria | Gentile di Larino | Molise | Dolce Agogia | Umbria |

| Corniolo | Campania | Olieddu | Sardinia | Favarol | Veneto |

| Ruveia | Campania | Nera di oliena | Sardinia | Grignan | Veneto |

| Ortolana | Campania | Bosana | Sardinia | Drobnica | Croatia |

| Racioppella campana | Campania | Nera di Villacidro | Sardinia | Aglandau | France |

| Cornia | Campania | Pidicuddara | Sicily | Verde Verdelho | Portugal |

| Pisciottana | Campania | Tonda iblea | Sicily | Picual | Spain |

| Pampagliosa | Campania | Cavalieri | Sicily | Masabi | Syria |

| Nostrana di Brisighella | Emilia-Romagna | Minuta | Sicily |

| RAUDPC Value | Susceptibility Class |

|---|---|

| 0–10% | Highly Resistant (HR) |

| 11–30% | Resistant (R) |

| 31–50% | Medium Susceptible (MS) |

| 51–70% | Susceptible (S) |

| 71–100% | Extremely Susceptible (E) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vizzarri, V.; Ienco, A.; De Rose, I.; Lombardo, L.; Godino, G.; Perri, E.; Polizzo, F. Comparative Assessment of Verticillium dahliae Tolerance in 77 Olive Cultivars. Crops 2026, 6, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/crops6010009

Vizzarri V, Ienco A, De Rose I, Lombardo L, Godino G, Perri E, Polizzo F. Comparative Assessment of Verticillium dahliae Tolerance in 77 Olive Cultivars. Crops. 2026; 6(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/crops6010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleVizzarri, Veronica, Annamaria Ienco, Ilaria De Rose, Luca Lombardo, Gianluca Godino, Enzo Perri, and Francesca Polizzo. 2026. "Comparative Assessment of Verticillium dahliae Tolerance in 77 Olive Cultivars" Crops 6, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/crops6010009

APA StyleVizzarri, V., Ienco, A., De Rose, I., Lombardo, L., Godino, G., Perri, E., & Polizzo, F. (2026). Comparative Assessment of Verticillium dahliae Tolerance in 77 Olive Cultivars. Crops, 6(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/crops6010009